Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is an emerging risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD). While liver biopsy is the gold standard for assessing fibrosis, noninvasive tests (NITs)—including fibrosis-4 (FIB-4), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score (NFS), and vibration-controlled transient elastography—are validated alternatives. However, their association with CKD stage in MASLD remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the association between NITs and various CKD outcomes in MASLD. A systematic search identified observational studies published between January 2014 to July 2024 following PRISMA were included. Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment were performed independently by multiple reviewers. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random-effects model. A total of 33 studies comprising 278,355 MASLD were included. High FIB-4 were associated with increased risks of CKD stage ≥ 3 (adjusted OR (AOR): 2.23; 95%CI 1.40–3.53) and advanced CKD including ESRD (OR: 2.75; 95%CI 1.27–5.96). High NFS was associated with albuminuria (AOR: 1.68; 95%CI 1.19–2.38) and CKD stage ≥ 3 (AOR: 2.52; 95%CI 1.78–3.58). Elevated liver stiffness showed a strong association with CKD stage ≥ 3 (AOR: 3.12; 95%CI 2.16–4.49). NITs may serve as indicators of CKD staging in MASLD. Future studies should explore whether targeting liver fibrosis could mitigate CKD progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fatty liver disease (FLD) or steatotic liver disease (SLD) is a noncommunicable disease associated with many conditions1,2,3,4 and has an increasing global incidence5,6. The progression of FLD to more severe stages including steatohepatitis and fibrosis has been associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma7. In addition, FLD has been shown to increase the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular diseases in several cohort studies8,9,10,11,12.

Although a related meta-analysis demonstrated an association between FLD and CKD, the definition of liver fibrosis and disease severity remains unclear. Liver biopsy constitutes the gold standard for diagnosing FLD severity13,14,15. However, two categories of noninvasive tests (NITs) —blood-based biomarker indices (fibrosis-4 [FIB-4] score, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) fibrosis Score [NFS], aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio [APRI]) and imaging-based vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) also known as liver stiffness measurement (LSM) have been validated as noninvasive methods to assess liver fibrosis and are increasingly used in real-world clinical settings16. Moreover, the sequence of CKD progression has not been explored in a related meta-analysis17. Only early composite outcome (albuminuria and glomerular filtration rate; eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) have previously been demonstrated18.

A knowledge gap remains concerning the ability of both categories of NITs to identify early kidney disease and the effects of the progressive stages of renal impairment in the FLD population. To offer comprehensive insights into the correlations, we concentrated on a substantial specific FLD population and the sequential detailed CKD outcomes regarding early albuminuria or proteinuria, the incidence of CKD at a minimum of stage 3, CKD progression to advanced stages, and ultimately end-stage renal disease (ESRD) through a systematic review and meta-analysis methodology.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vajira Hospital (approval number: COE: 005/2024 X). The systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and were registered in PROSPERO (2024CRD42024564627).

Search strategy

Each article’s eligibility was assessed using a stepwise procedure. First, we queried reports recorded in the Medline and Scopus databases from January 2014 to July 2024, using the following MeSH terms, their entry terms, and free-text keywords: “Fatty Liver (MeSH Unique ID: D005234), Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (MeSH Unique ID: D065626), Liver Cirrhosis (MeSH Unique ID: D008103), Elasticity Imaging Techniques (MeSH Unique ID: D054459), Renal Insufficiency, Chronic (MeSH Unique ID: D051436), Proteinuria (MeSH Unique ID: D011507) and Kidney Failure, Chronic (MeSH Unique ID: D007676).” A comprehensive, systematic search strategy was fully described in the Supplementary File.

Study selection

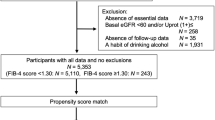

The study included adults aged over 18 years, diagnosed with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). MASLD is characterized by hepatic steatosis in individuals consuming less than 140 g of alcohol weekly for females and less than 210 g for men, accompanied by at least one cardiometabolic risk factor, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, or metabolic dysregulation. Although transitioning from NAFLD to MASLD, the MASLD-defined population are interchangeable with existing NAFLD literature19. Levels were categorized according to low, intermediate and high score for each NIT including; NFS: (High ≥ 0.676, Intermediate −1.455—0.675, Low < −1.455); FIB-4: (High ≥ 2.67, Intermediate 1.30–2.669, Low < 1.30); and LSM: (High > 8 kPa, Intermediate 6–8 kPa, Low < 6 kPa).

Various aspects of CKD outcome were assessed (albuminuria/proteinuria, urine albumin creatinine ratio [UACR]) > 30 mg/g creatinine, the occurrence of CKD ≥ stage 3 (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), CKD progression (progression or deterioration to a higher stage) and advanced stage (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or ESRD (eGFR) < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2). Observational including cross-sectional, cohort studies that reported the association between liver fibrosis and CKD were included.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

The titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved were independently screened for appropriateness by the first author (SS, hepatologist) and co-author (NT, clinical data scientist). Endnote, Version 21 was used as the screening tool. All literature identified through the database search was included. The researchers independently reviewed and were blinded to each other’s decisions.

Exclusion criteria

After screening all abstracts, we excluded guidelines/reviews, conference abstracts, editorial comments, letters to the editors and case reports/case series. Nonrelevant data such as nonfatty liver populations, animal studies or non-CKD outcomes, no NIT evaluations, non-standard criteria of grouping NITs, duplicated publications or previous meta-analyses were deleted. Studies not published in full text or in English were also excluded. Next, two authors (SS and NT) independently reviewed the full texts of the selected articles to extract detailed pertinent data. A third author (WR, clinical epidemiologist) reviewed all full texts to validate the extracted data. Disagreements regarding study selection were resolved by discussion with a third author (WR), and two other expert nephrologists (PS and TT) clarified the CKD endpoints. All five review team members checked all final input data.

Data extraction

We extracted the author’s name, publication year, study design, study site, number of MASLD participants, characteristics of participants such as age, percentage of male participants, body mass index, percentage of participants with diabetes, NITs for liver fibrosis assessment including FIB-4, NFS, LSM, APRI, individual kidney outcome and risk of bias quality of each study. For the NITs, we recorded the categorized groups according to the standard cutoff for each index. Kidney outcomes were defined as the UACR, CKD stage ≥ 3, CKD progression and end stage renal disease (ESRD). The Newcastle–Ottawa assessment was used to determine the qualified risk of bias of each cross-sectional observational and cohort study using star scoring systems. For cross-sectional studies, scores of 7–9, 5–6, and < 4 were defined as good, satisfactory and unsatisfactory, respectively. For cohort studies, scores of 9, 7–8 and < 6 indicated low, intermediate and high risk of bias, respectively (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the quantitative data are reported as means with standard deviations or percentages. For kidney outcomes, changes were compared with pooled unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each classified outcome. The range of the fibrosis severity group was recorded according to the cutoff values of each NITs, and individual interest outcomes were compared in terms of the OR of the high reference group with the low, and intermediate groups. Heterogeneity was assessed using the degree of heterogeneity (I2); I2 > 25%, > 50% and > 75% were defined as low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively. All outcomes were assessed using a random-effects model. Publication bias was explored using Egger’s test.

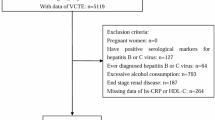

Results

Search results totaled 2,982 studies from Medline (1,386 articles) and Scopus (1,596 articles). Of these, the following were excluded: duplicates (11), year before 2014 (416), book/conference proceedings (260), case report/case series (36), systematic review/meta-analyses (210), narrative review/literature reviews (625), perspective and editorial comments (41), consensus/guidelines/guidance (37), and reports (14). After multiple rounds of discussion to calibrate and reach consensus among all reviewers regarding the categorization of nonstandard NITs and outcome definitions, 33 of the remaining 1,332 eligible articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis, representing a total of 278,355 MASLD participants. (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Of the 33 studies included in the meta-analysis, among the 17 articles reporting the association of FIB-4 with renal endpoints, 4 studies examined UACR, 13 studies investigated the presence of CKD stage ≥ 3, and 4 studies assessed the presence of advanced CKD stage and ESRD. Among the 21 articles reporting the association of NFS with renal endpoints, 6 studies examined UACR, 16 studies investigated the presence of CKD stage ≥ 3 and 2 studies assessed the presence of ESRD. Ninth articles presented the association between LSM and renal endpoints, all addressed the presence of CKD stage ≥ 3. Three articles reported an association between APRI and CKD stage ≥ 3 (Table 1).

Association between fibrosis-4 and chronic kidney disease outcome

FIB-4 and the UACR A meta-analysis of four studies20,21,22,23 showed that a high FiB-4 level was associated with a higher risk of UACR than a low FIB-4 level (unadjusted OR 1.427 [95% CI 1.165, 1.747] p = 0.001; I2 = 0, p = 0.953; Egger’s test = 0.009).

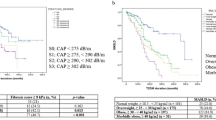

FIB-4 and CKD stage ≥ 3 Our meta-analysis20,21,22,24,25,26,27 showed that a high FiB-4 was associated with a higher risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 in the univariable analysis studies (unadjusted OR 2.712 [95% CI 2.012, 3.656] p < 0.001; I2 = 79.222, p < 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.518) Consistent with the studies of multivariable analysis20,28,29,30,31higher FIB-4 associations were also shown with increased CKD stage ≥ 3 outcomes (adjusted OR 2.225 [95% CI 1.401, 3.533] p = 0.001; I2 = 67.545, p = 0.009; Egger’s test = 0.014). Regarding the FIB-4 per 1 score in univariable analysis studies27,29,32,56 we found a relationship between FIB-4 and CKD stage ≥ 3 (unadjusted mean difference 0.443 [95% CI 0.311, 0.575] p < 0.001; I2 = 55.36, p = 0.106; Egger’s test = 0.712). However, in the multivariate analysis studies the associative trend was less significant20,33 (adjusted OR 1.101 [95% CI 0.946, 1.280] p = 0.214; I2 = 22.808, p = 0.274).

FIB-4 and advanced CKD stage including ESRD

In the four univariable analysis studies25,34,35,36, FIB-4 was associated with advanced CKD stage, and ESRD (unadjusted OR 2.751 [95% CI 1.269, 5.963], p = 0.010; I2 = 92.430, p < 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.113).

Association between NAFLD fibrosis score and chronic kidney disease outcome

NFS and the UACR Our meta-analysis of univariable analysis studies12,21,22,23,32,33 demonstrated that an elevated NFS correlated with an increased risk of UACR compared to a low NFS (unadjusted OR 3.466 [95% CI 1.901, 6.319] p < 0.001; I2 = 93.950, p < 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.142). Consistent with another two studies23,33 the adjusted OR for UACR exhibited a significant association (adjusted OR 1.684 [95% CI 1.191, 2.380] p = 0.003; I2 = 0, p < 0.454).

NFS and CKD stage ≥ 3 Our meta-analysis12,21,22,25,26,27,37,38,39,40 showed that elevated NFS levels correlated with an increased risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 (unadjusted OR 3.022 [95% CI 1.784, 5.119] p < 0.001; I2 = 96.876; Egger’s test = 0.08). Studies that reported multivariate analyses26,28,30,31,39,40,41,42 demonstrated that elevated NFS values were also associated with increased CKD stage ≥ 3 outcomes (adjusted OR 2.522 [95% CI 1.779, 3.575], p < 0.001; I2 = 75.590, p < 0.001; Egger’s test 0.04). However, the association of NFS per 1-point increase and CKD showed only a non-significant trend in two studies21,43 (unadjusted OR 2.330 [95% CI 0.910, 5.965] p = 0.078; I2 = 89.983, p = 0.002; Egger’s test NA) and (adjusted OR 1.236 [95% CI 0.921, 1.657] p = 0.158; I2 = 55.766, p = 0.133; Egger’s test NA).

NFS and ESRD NFS was associated with ESRD in two studies35,36 (unadjusted OR 5.191 [95% CI 1.148, 23.472], p = 0.032; I2 = 97.586, p < 0.001; Egger’ test NA).

Association between liver stiffness measurement and chronic kidney disease outcome

LSM and CKD stage ≥ 3 Six studies44,45,46,47,48,49 showed that elevated LSM correlated to an increased risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 compared with that of lower LSM (unadjusted OR 2.753 [95% CI 1.029, 7.361], p = 0.044; I2 = 95.326, p < 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.527). These results were consistent with the results of the multivariate analysis studies44,45,46,47,49,50 (adjusted OR 3.116 [95% CI 2.162, 4.489], p < 0.001; I2 = 0, p = 0.529; Egger’s test = 0.012). However, only a nonsignificant trend was observed between LSM per 1-point increase and CKD stage ≥ 3 in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses32,46,51,56 (unadjusted OR 1.412 [(95% CI 0.955, 2.089], p = 0.084; I2 = 86.511, p = 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.120) and (adjusted OR 1.237 [95% CI 0.973, 1.573], p = 0.082; I2 = 81.619, p = 0.004; Egger’s test = 0.084).

Association between AST/platelet ratio and chronic kidney disease outcome

APRI and CKD stage ≥ 3 The analysis of three studies22,27,37 demonstrated an association between the APRI and CKD at least stage 3 (unadjusted OR 3.621 [95% CI 1.217, 10.772], p = 0.021; I2 = 96.897, p < 0.001; Egger’s test = 0.827).

Investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was performed in unadjusted OR and adjusted OR that had adequate included paper. High FIB-4 level was associated with a higher risk of UACR than a low FIB-4 level in only Asia country and cross-sectional study (unadjusted OR 1.404 [95% CI 1.129, 1.745] p = 0.002); unadjusted OR 1.443 [95% CI 1.134, 1.837] p = 0.003, respectively). High FIB-4 was associated with a higher risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 in both Asia and Europe countries. (unadjusted OR 2.246 [95% CI 1.803, 2.799] p < 0.001; unadjusted OR 4.780 [95% CI 2.677, 8.536] p < 0.001, respectively). Cross-sectional and cohort studies provided the significant association between high FIB-4 and high risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 (unadjusted OR 2.499 [95% CI 1.909, 3.270] p < 0.001; unadjusted OR 2.938 [95% CI 1.587, 5.441] p < 0.001, respectively).

Higher FIB-4 associations were also shown with increased CKD stage ≥ 3 outcomes in Europe and US countries (adjusted OR 7.250 [95% CI 2.510, 20.940] p < 0.001; adjusted OR 2.431 [95% CI 1.473, 4.014], p = 0.001, respectively). Cross-sectional and cohort studies provided the significant association between high FIB-4 and high risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 (adjusted OR 2.431 [95% CI 1.473, 4.014] p = 0.001, adjusted OR 2.249 [95% CI 1.162, 4.351] p = 0.016, respectively. FIB-4 was associated with advanced CKD stage, and ESRD in Europe and US (unadjusted OR 2.580 [95% CI 1.845, 3.607], p < 0.001, unadjusted OR 6.977 [95% CI 4.923, 9.888], p < 0.001, respectively). Only cohort study demonstrated the significant association between FIB-4 and advance CKD stage, and ESRD. (unadjusted OR 3.621 [95% CI 1.756, 7.469], p < 0.001).

Elevated NFS correlated with an increased risk of UACR compared to a low NFS in Asia and US (unadjusted OR 2.256 [95% CI 1.788, 2.847] p < 0.001; unadjusted OR 7.933 [95% CI 5.382, 11.693] p < 0.001, respectively). Cross-sectional study provided the significant correlated between NFS and UACR (unadjusted OR 3.466 [95% CI 1.901, 6.319] p < 0.001).

Elevated NFS levels correlated with an increased risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 in all regions including Asia, Europe and US (unadjusted OR 2.313 [95% CI 1.393, 3.840], unadjusted OR 4.365 [95% CI 1.021, 18.664], unadjusted OR 5.396 [95% CI 1.796, 16.210], respectively). Cross-sectional and cohort also provide the significant association between NFS and CKD stage ≥ 3 (unadjusted OR 3.017 [95% CI 1.189, 7.659], and unadjusted OR 3.023 [95% CI 2.620, 3.489], respectively). High NFS scores were also associated with increased CKD stage ≥ 3 outcomes in all regions including Asia, Europe and US (adjusted OR 1.955 [95% CI 1.507, 2.536] p < 0.001; adjusted OR 10.922 [95% CI 1.430, 83.423] p = 0.021, adjusted OR 2.248 [95% CI 1.224, 4.129] p = 0.009, respectively).

Elevated LSM correlated to an increased risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 compared with that of lower LSM in only Asia (unadjusted OR 3.441 [95% CI 1.208, 9.804] p = 0.021). High LSM were associated with risk of CKD stage ≥ 3 in all regions including Asia, Europe, US countries. (adjusted OR 5.283 [95% CI 2.471, 11.295] p < 0.001; adjusted OR 3.618 [95% CI 1.915, 6.836] p < 0.001, and adjusted OR 2.110 [95% CI 1.216, 3.661] p = 0.008, respectively) and all study designs (cross-sectional: adjusted OR 2.924 [95% CI 1.988, 4.301] p < 0.001 vs. cohort: adjusted OR 5.400 [95% CI 1.733, 16.822] p = 0.004).

Discussion

The pathophysiological connection between MASLD and CKD encompasses several interconnected processes mostly influenced by metabolic abnormalities and chronic inflammation. The primary culprit is insulin resistance, which facilitates hepatic fat storage, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, hence contributing to liver fibrosis and renal damage. Fructose-induced elevation of uric acid, coupled with gut dysbiosis, results in heightened oxidative stress and the generation of uremic toxins, which further compromise renal function. Dysregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and endoplasmic reticulum stress also contribute to fibrosis and inflammation in both organs. The same molecular pathways underscore MASLD as a systemic disorder rather than merely a liver disease, substantially increasing the risk of CKD 52,53.

This meta-analysis builds upon related research by incorporating a more comprehensive evaluation of noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment tools in relation to CKD outcomes within a large, specific MASLD population. These findings highlight a significant relationship between elevated fibrosis scores and an increased risk of CKD, reinforcing the notion that the severity of liver fibrosis plays a crucial role in kidney dysfunction.

Subgroup analyses including race and study designs were performed to explore the heterogeneity that might come from the potential variability across studies. The stronger associations were consistently observed in Asian and European cohorts compared with U.S. The magnitude of risk estimates was generally higher in cohort than in cross-sectional studies. This regional variation may reflect underlying differences in metabolic risk burden and genetic susceptibility that influence the detection of both MASLD and CKD. In term of age, gender, and diabetic status which are the important factors for CKD status, we highlight the effects of them by using the adjusted models (Table 2). Overall, the adjusted models also demonstrated the same way as univariable. That means the association between non-invasive liver biomarker and CKD still consistent. Additionally, we emphasized that FIB-4 corresponds with later stages of CKD and ESRD, suggesting that heightened fibrosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in MASLD may accelerate the progression of CKD.

In the aspect of non-liver outcome, our meta-analysis regarding dynamic FIB-4 and CKD progression over an average three-year follow-up was unfeasible because of the discrepancies in categorical and continuous FIB-4 measurements between them. Following a 4-year follow-up, an elevated FIB-4 was associated with ESRD prognosis; however, adjustments for comorbidities were not incorporated. Despite the updated guidelines, the serial blood-based FIB-4 cannot accurately predict the dynamic change of liver fibrosis51. The utility of baseline or dynamic FIB-4 in monitoring the dynamic CKD progression and ESRD is pertinent for long term evaluations.

The NFS is widely used to estimate the progression of liver fibrosis and incorporates both liver function and significant metabolic risk factors. Diabetes, a component of NFS, is associated with MASLD and accelerated liver fibrosis. The strength of the NFS lies in its robust connection with early renal outcomes, demonstrating consistency across more than 1000 instances of MASLD with diabetes. In addition to screening for early albuminuria in diabetes, incorporating NFS assessment for MASLD with concurrent diabetes may enhance early recognition of renal disease. To gain a deeper understanding of MASLD and its correlation with metabolic risk in obesity, investigating this link is vital. Similarly, the significant heterogeneity was largely attributable to regional differences and the metabolic composition of included populations. Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent positive associations across Asia, Europe, and the U.S., reinforcing the robustness of the relationship between higher NFS and renal dysfunction despite methodological and population variability.

In contrast, heterogeneity in studies assessing LSM appeared primarily due to technical variation in device calibration, operator expertise which are known to affect liver stiffness measurements. VCTE-derived LSM, widely used in assessing liver fibrosis, has been featured in a limited number of meta-analyses. Both liver inflammation and fibrosis affected LSM scores. Fewer studies on VCTE-derived LSM, which may limit the robustness of conclusions drawn about this specific test. Further investigation is needed to clarify the predictive accuracy and consistency of the LSM score. In the context of liver fibrosis, significant confounders affecting the LSM threshold for advanced fibrosis include hepatic inflammation and elevated BMI, which can lead to overestimating LSM values54,55. Despite fewer studies, our findings indicate that elevated LSM is a reliable indicator of CKD risk, particularly in Asian populations.

Although some heterogeneity remained, the direction of effect across all analyses was remarkably consistent, suggesting that the observed variability is quantitative rather than qualitative. This indicates that while effect sizes vary, the underlying relationship between liver fibrosis severity and CKD risk is stable across regions and study types. Understanding the strength of each NIT, provides a deeper understanding of their utility in different CKD outcomes in a large MASLD population, offering a more granular perspective concerning CKD progression. By addressing prior gaps and leveraging contemporary data, our study provides strong evidence for integrating noninvasive fibrosis screening not only for hepatology care but also clinical risk stratification models for CKD events in individuals newly diagnosed with MASLD.

This study encountered limitations. First, the major limitations, such as the observational nature of included studies and potential residual confounding, which hamper the strength of causal associations. Second, the heterogeneity in fibrosis severity thresholds could have potentially led to inconsistencies and would have likely introduced misclassification bias. Without a standardized approach to categorizing fibrosis severity, drawing clear conclusions remains challenging.

Regarding publication bias, Egger’s tests demonstrated significant small-study effects in a few analyses, indicating potential publication bias favoring positive findings. Such bias could partly overestimate pooled effect sizes; however, the inclusion of large population-based cohorts mitigates this concern by anchoring the estimates. The consistent directionality of associations across multiple NITs and analytic models further supports the reliability of the overall findings despite these limitations. From our study, the follow up was limited which again makes it difficult to understand the dynamic relationship between liver fibrosis and kidney disease progression. In the future, there is a necessity for larger prospective studies that standardize NIT thresholds and CKD outcome measures to gain a comprehensive knowledge of this relationship’s dynamics. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to establish causality, as well as interventional trials to assess whether modifying liver fibrosis severity can lead to improved renal outcomes.

Conclusion

Greater liver fibrosis burden, as assessed by noninvasive indices, consistently correlates with higher CKD risk and progression across diverse MASLD populations. Our meta-analysis underscores the strong association between noninvasive liver fibrosis markers and various CKD outcomes. These findings emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary approach for MASLD management incorporating both hepatologists and nephrologists in patient care. Given the growing global burden of MASLD and CKD, the early detection of kidney dysfunction using simple NITs could facilitate timely interventions to mitigate disease progression.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Sethasine, S., Suthasmalee, S., Tangjitgamol, S. & Phaloprakarn, C. Contraception and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. Contraception 145, 110860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2025.110860 (2025).

Younossi, Z. M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 70(3), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033 (2019).

Sethasine, S. & Phaloprakarn, C. Relationship between breastfeeding and hepatic steatosis in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Int Breastfeed J. 19(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-024-00684-3 (2024).

Phaloprakarn, C. & Sethasine, S. Association between glucose intolerance and fatty liver disease in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus in urban Thailand: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 15(5), e097114. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-097114 (2025).

Grander, C., Grabherr, F. & Tilg, H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathophysiological concepts and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 119(9), 1787–1798. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvad095 (2023).

Targher, G., Tilg, H. & Byrne, C. D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A multisystem disease requiring a multidisciplinary and holistic approach. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6(7), 578–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00020-0 (2021).

Sethasine, S., Simasingha, N., Ratana-Amornpin, S. & Mahachai, V. Real world for management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A large population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2023.2209686 (2023).

Chalasani, N. et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 67(1), 328–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29367 (2018).

Bilson, J., Mantovani, A., Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. Steatotic liver disease, MASLD and risk of chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab. 50(1), 101506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2023.101506 (2024).

Wang, T. Y. et al. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 18(4), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00519-y (2022).

Sharma, N., Sircar, A., Anders, H. J. & Gaikwad, A. B. Crosstalk between kidney and liver in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Arch Physiol Biochem. 128(4), 1024–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2020.1745851 (2022).

Sun, D. Q. et al. MAFLD and risk of CKD. Metabolism 115, 154433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154433 (2021).

Mantovani, A. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: An updated meta-analysis. Gut 71(1), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154433 (2021).

Musso, G. et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11(7), e1001680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001680 (2014).

Mantovani, A. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of incident chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 79, 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.11.003 (2018).

Berzigotti, A. et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis: 2021 update. J Hepatol. 75(3), 659–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.025 (2021).

Supriyadi, R., Yanto, T. A., Hariyanto, T. I. & Suastika, K. Utility of non-invasive liver fibrosis markers to predict the incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD): A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 17(8), 102814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2023.102814 (2023).

Ciardullo S, Ballabeni C, Trevisan R, Perseghin G (2022) Liver Stiffness, Albuminuria and Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with NAFLD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomolecules. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010105.

Ratziu, V. & Boursier, J. Confirmatory biomarker diagnostic studies are not needed when transitioning from NAFLD to MASLD. J Hepatol. 80(2), e51–e52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.017 (2024).

Saito, H. et al. High FIB4 index is an independent risk factor of diabetic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep. 11(1), 11753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88285-6 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. The association between NAFLD and risk of chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. Ther Adv Chronic Dis https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622321104864 (2021).

Ciardullo, S. et al. Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes using non-invasive scores and association with diabetic complications. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000904 (2020).

Han, E. et al. Hepatic fibrosis is associated with total proteinuria in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(33), e21038. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021038 (2020).

Mantovani, A. et al. MASLD, hepatic steatosis and fibrosis are associated with the prevalence of chronic kidney disease and retinopathy in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 50(1), 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2023.101497 (2024).

Nah, E. H. et al. Chronic kidney disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease at primary healthcare centers in Korea. PLoS ONE 17(12), e0279367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279367 (2022).

Seo, D. H. & Kim, S. H. Advanced liver fibrosis is associated with chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab J. 46, 630–639. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0130 (2022).

Sinn, D. H. et al. Development of chronic kidney disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A cohort study. J Hepatol. 67(6), 1274–1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.024 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Fibrosis risk in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to chronic kidney disease in older type 2 diabetes patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 107(9), e3661–e3669. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgac382 (2022).

Seko, Y. et al. FIB-4 index and diabetes mellitus are associated with chronic kidney disease in japanese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010171 (2019).

Önnerhag, K., Hartman, H., Nilsson, P. M. & Lindgren, S. Non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can predict future metabolic complications and overall mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Scand J Gastroenterol. 54(3), 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1583366 (2019).

Wijarnpreecha, K., Thongprayoon, C., Scribani, M., Ungprasert, P. & Cheungpasitporn, W. Noninvasive fibrosis markers and chronic kidney disease among adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver in USA. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 30(4), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001045 (2018).

Deng, Y., Zhao, Q. & Gong, R. Association between metabolic associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2017–2018. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 14, 1751–1761. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S292926 (2021).

Williams, K. H., Burns, K. & Twigg, S. M. Differing clinical phenotype for higher alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) compared with high-risk NAFLD fibrosis score in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complic. 32(3), 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.12.010 (2018).

Sanyal, A. J. et al. Validation of a clinical risk-based classification system in a large nonalcoholic fatty liver disease real-world cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21(11), 2889–2900 (2023).

Hydes, T. J. et al. The impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis on adverse clinical outcomes and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study using the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 21(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02891-x (2023).

Chen, S., Pang, J., Huang, R., Xue, H. & Chen, X. Association of MAFLD with end-stage kidney disease: A prospective study of 337,783 UK Biobank participants. Hepatol Int. 17(3), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-023-10486-0 (2023).

Noureddin, N., Noureddin, M., Singh, A. & Alkhouri, N. Progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-associated fibrosis in a large cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes. Dig Dis Sci. 67(4), 1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-06955-x (2022).

Hsieh, M. H. et al. Higher NAFLD fibrosis score is associated with impaired eGFR. J Formos Med Assoc. 119(1 Pt 3), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2019.07.007 (2020).

Sesti, G. et al. Association between noninvasive fibrosis markers and chronic kidney disease among adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS ONE 9(2), e88569. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088569 (2014).

Zuo, G. et al. New nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis progression associate with the risk of incident chronic kidney disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 106(10), e3957–e3968. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab425 (2021).

Chen, P. C. et al. The correlation between fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 119(1 Pt 1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2019.02.010 (2020).

Cen, C., Fan, Z., Ding, X., Tu, X. & Liu, Y. Associations between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and abdominal obesity: A national retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 14(1), 12645 (2024).

Hu, Q., Chen, Y., Bao, T. & Huang, Y. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with chronic kidney disease: A Chinese population-based study. Ren Fail. 44(1), 1996–2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2022.2144373 (2022).

Nampoothiri, R. V. et al. Renal dysfunction in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to the presence of diabetes mellitus and severity of liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 9(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2017.12.005 (2019).

Jung, C. Y. et al. Advanced liver fibrosis measured by transient elastography predicts chronic kidney disease development in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 65(3), 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05627-9 (2022).

Mikolasevic, I. et al. Significant liver fibrosis, as assessed by fibroscan, is independently associated with chronic vascular complications of type 2 diabetes: A multicenter study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 177, 108884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108884 (2021).

Mantovani, A. et al. Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using liver stiffness measurement and its association with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 46(4), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2019.11.004 (2020).

Yeung, M. W. et al. Advanced liver fibrosis but not steatosis is independently associated with albuminuria in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.020 (2017).

Lombardi, R. et al. Liver fibrosis by FibroScan(®) independently of established cardiovascular risk parameters associates with macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Liver Int. 40(2), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14274 (2020).

Zhang, W. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease-related hepatic fibrosis increases risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 36(6), 802–810. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000002767 (2024).

Sterling, R. K. et al. AASLD practice guideline on blood-based noninvasive liver disease assessment of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Hepatology 81(1), 321–357. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000845 (2025).

Heda, R. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver and chronic kidney disease: Retrospect, introspect, and prospect. World J Gastroenterol. 27(17), 1864–1882. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1864 (2021).

Theofilis, P., Vordoni, A. & Kalaitzidis, R. G. Interplay between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: Epidemiology, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and treatment considerations. World J Gastroenterol. 28(39), 5691–5706. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i39.5691 (2022).

Patel, K. & Sebastiani, G. Limitations of non-invasive tests for assessment of liver fibrosis. JHEP Rep. 2(2), 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100067 (2020).

Singh, A., Sohal, A. & Batta, A. Recent developments in non-invasive methods for assessing metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 30(39), 4324–4328. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i39.4324 (2024).

Qin, S., Wang, S., Wang, X., Wang, J. Liver stiffness assessed by transient elastography as a potential indicator of chronic kidney disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33(2) https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.2019.33.issue-210.1002/jcla.22657 (2019).

Funding

This study supported by the Navamindradhiraj University Research Fund and the Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital, Navamindradhiraj University and the Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund, Chulalongkorn University (The Review Article Grant; Grant No.RA68007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS, NT, TT, WR, and PS contributed to the conception and design of the study. SS, NT, and WR contributed to data collection. SS, WR and PS contributed to statistical analysis and data interpretation. SS, TT, and WR contributed to drafting of the article. PS critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sethasine, S., Trakarnvanich, T., Ruamtawee, W. et al. Association of noninvasive tests of liver fibrosis with chronic kidney disease in MASLD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 42681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26752-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26752-0