Abstract

Cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine (c-OPLL) is an intractable disease that impairs activities of daily living and quality of life. There are few reports on patients’ return to work (RTW) after surgery. The aim of this study was to investigate the RTW status and its associated factors after c-OPLL surgery through a nationwide multicenter questionnaire survey and to provide reference evidence for determining the future treatment of this disease. We were able to study 286 patients (205 males, 81 females) from 13 institutions. We analyzed RTW in 198 patients, excluding 88 patients who were unemployed before surgery. RTW was confirmed in 151 patients (124 males, 27 females), and RTW rate was 76.3%. Significant differences were observed between RTW + and—groups in age, body mass index, preoperative workload, and preoperative JOA score. Notably, this study was the first to demonstrate that postoperative residual neuropathic pain is a significant factor associated with RTW after c-OPLL surgery. The results of this study will provide useful information for determining future treatment plans for patients with an eye toward returning to work after surgery, and may also have an impact on surgical indications for this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine (OPLL), first described by Key in 18381, is characterized by the heterotopic bone formation in the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Cervical OPLL (c-OPLL) can result in neurological compromises through compression of spinal cord and nerve roots2,3. C-OPLL is an intractable disease that reduces activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life (QOL) and results in economic losses.

Due to its high relevance for the individual and society, return to work (RTW) has become an important outcome measure in recent years4. There are various reports regarding RTW after surgery for lumbar degenerative disease5, but there are significantly fewer reports regarding those for cervical degenerative disease6. Although there is a significant increase in evidence supporting the effectiveness of surgery in c-OPLL2,3, there are very few reports on postoperative QOL7, and even fewer on postoperative RTW. RTW following surgery not only has positive effects for the individual patient but also for society in general. A better understanding of the factors that determine which patients are more (or less) likely to return to work after surgery may improve physician–patient communication in clinical practice and allow surgeons to quantify expectations throughout treatment.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the RTW status and its associated factors after c-OPLL surgery through a nationwide multicenter study and to provide reference evidence for determining the future treatment of this disease.

Results

In the present study, 151 patients (124 males and 27 females) out of 198 patients (160 males, 38 females) who were employed preoperatively were able to return to work, for a RTW rate of 76.3%. Patient demographics for the RTW + /- groups are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were observed between the two groups in age, body mass index (BMI), preoperative workload, and preoperative Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score. The RTW + group was significantly younger, had a significantly lower BMI, had a significantly higher preoperative workload, and had a significantly better preoperative JOA score. There were no significant differences in history of diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, or spinal surgery at other sites. In the postoperative RTW + group, 81.5% of patients were employed full-time, compared with 78.7% in the postoperative RTW- group with no significant difference between the two groups (Table 2). The occupations before surgery were light sedentary labor for 92 patients, light standing labor for 57 patients, and heavy labor for 49 patients. There were no significant differences in the distribution of the occupation categories in RTW + /- group (Table 2). Kaplan–Meier curves showed cumulative RTW rates, with a median time to RTW of 120 ± 15.4 days (Fig. 1).

Radiographical assessments revealed that alignment of cervical spine, K-line condition, spinal canal occupying ratio (COR), the presence of an intramedullary signal intensity change on T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and type of OPLL were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3). The RTW + group had significantly better scores in all postoperative Japanese Orthopaedic Association Cervical Myelopathy Evaluation Questionnaire (JOACMEQ) domains (Table 4).

The surgical procedures performed were laminoplasty (LMP), posterior decompression and fusion (PDF), anterior decompression and fusion (ADF), and anterior–posterior combined surgery (AP combined). To clarify the impact of surgical procedures on patients’ RTW, we investigated the distribution of surgical procedures according to whether or not patients returned to work (Table 5). There was no significant difference in the distribution of surgical procedures between those who returned to work and those who did not.

To investigate the association between postoperative residual pain and RTW, this study used the pain items from the JOACMEQ and the painDETECT Questionnaire (PDQ). According to the visual analog scale (VAS) assessment of pain in JOACMEQ, VAS values were significantly higher in the RTW- group, except for chest tightness (Table 6). Evaluation by PDQ showed that postoperative residual neuropathic pain (NeP) was significantly higher in the RTW- group (Table 6).

To elucidate the associated factors for success in achieving postoperative RTW, we employed multivariate logistic analysis. Multivariate analysis revealed that age, preoperative workload, preoperative JOA score, and postoperative residual NeP were independent factors significantly associated with RTW after c-OPLL surgery (Table 7).

Discussion

This is the first nationwide multicenter study on RTW after surgery for c-OPLL. In addition, this study is the first to demonstrate the impact of postoperative residual pain including NeP on RTW after c-OPLL surgery.

There are various reports regarding RTW after surgery for lumbar degenerative disease5, but there are significantly fewer reports regarding those for cervical degenerative disease6. The RTW rate after surgery in patients with degenerative cervical disease has been reported to be approximately 60% to 80%, although this varies depending on the cohort and the time of evaluation4,8,9,10.

There are even fewer reports on RTW after c-OPLL surgery. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one English literature on RTW after c-OPLL surgery11. In 2003, Kamizono et al. reported on the postoperative RTW of patients who underwent surgical treatment for c-OPLL using exclusively open-door LMP11. The study included postoperative patients from a single institution who were aged 70 years or younger at the time of surgery, excluding patients who had been involved in traffic- or work-related accidents. The authors reported that the RTW rate after surgery was 53%, with lower rates in those who performed heavy labor, worked at heights, or drove professionally. Occupation, pre- and postoperative severity of myelopathy were significantly correlated with RTW, and they suggested that these factors can serve as a reference when designing postoperative vocational rehabilitation programs.

On the other hand, the present study is a nationwide multicenter study, and there are no restrictions on age or surgical procedure as long as the patient was employed before surgery. The RTW rate in the present study was 76.3%, which is higher than that reported by Kamizono et al.; however, due to differences in the cohorts studied, definitions of RTW, and the eras studied, it is inherently difficult to directly compare RTW rates across studies. Furthermore, we believe that it is more important to understand the factors associated with RTW than to compare RTW rates themselves. Previous reports in cervical degenerative disease have shown that factors such as employment immediately before surgery, younger age, having a high level of education, full-time employment, low-intensity occupation, short duration of symptoms, and not receiving worker’s compensation are favorable for RTW after cervical spine surgery4,12,13. In the present study, multivariate analysis revealed that age, preoperative workload, preoperative JOA score, and postoperative residual NeP were independent factors significantly associated with RTW after c-OPLL surgery. Previous reports on degenerative cervical myelopathy have shown the significant advantage of anterior cervical surgery for RTW12, but this study did not find any significant differences between surgical procedures. One of the likely explanations for this result is that the participating centers were experts in treating c-OPLL, and appropriate surgical procedures may have been selected for each case. Another likely explanation is the evolution of surgical procedures. The most common surgical procedure for cervical OPLL is LMP2,3. However, patients with thick ossification and/or kyphosis (i.e., K-line—patients) have poor neurological recovery after LMP14,15. Even in such patients, ADF can ideally relieve spinal cord compression by directly removing the OPLL, resulting in good postoperative recovery16. However, ADF for c-OPLL tends to be less popular due to its technical complexity and the complicated perioperative management, such as complications specific to anterior surgery (e.g., swallowing disorders, respiratory disorders, etc.)16,17. With the recent advances in spinal instrumentation surgery, PDF has become a possible alternative procedure for K-line—c-OPLL14,18. Further investigation is needed to determine the impact of changes in surgical procedures for c-OPLL on postoperative RTW.

In recent years, research into pain in c-OPLL has attracted the attention of researchers in this field. Neck pain after c-OPLL surgery is well recognized as one of the unresolved postoperative complications. It has been reported that factors affecting neck pain after c-OPLL surgery are related to neurological recovery, which is associated with its reduction19, and posterior cervical surgery and the number of fusion levels, which is associated with its worsening20. More recent studies have reported a high prevalence of residual NeP after c-OPLL surgery, with risk factors including older age, longer duration of disease, poor preoperative JOA score, and low cervical lordotic angle21,22. These results suggest that improving residual neck pain and NeP after c-OPLL surgery is a very important issue. Indeed, it has been reported that poor pain control after elective spine surgery was an independent risk factor for poor surgical outcome23. Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made in developing algorithms and tools for the diagnosis of NeP; however, NeP remains a significant problem without an effective solution for all patients24. Establishing a treatment for NeP is a challenge that we must overcome in the near future.

Despite extensive clinical research into degenerative cervical myelopathy, consensus regarding the optimal timing of surgical intervention remains controversial25,26. Guidelines for degenerative cervical myelopathy strongly recommend surgical treatment for patients with spinal cord compression with moderate to severe myelopathy25. However, recommendations for surgical treatment for the patients with mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic spinal cord compression have not yet been established. Although there is less evidence about c-OPLL than about “general” cervical degenerative diseases, studies of its natural history have shown that it exhibits a progressive nature of ossifying lesions27. Furthermore, it has been reported that compared with “general” degenerative cervical myelopathy, c-OPLL may be at higher risk of worsening myelopathy after minor trauma28. Given this background, the surgical indications for c-OPLL may differ from those for “general” degenerative cervical myelopathy. In the current clinical practice guidelines on the management of ossification of the spinal ligament2, consistent with recommendations for surgical treatment for patients with “general” cervical degenerative disease, surgery is recommended for patients with moderate and/or progressive myelopathy due to c-OPLL. On the other hand, prophylactic surgery in patients with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic c-OPLL should be undertaken with caution, as there is no evidence to recommend such treatment2. In addition, while the current clinical practice guidelines on the management of ossification of the spinal ligament mention conservative treatment for c-OPLL, they do not mention postoperative rehabilitation programs or RTW2. Median RTW time in the present study was 120 ± 15.4 days. We believe this information is important for planning treatment for patients who aim to return to work after surgical treatment for C-OPLL, but further evidence is needed.

In the literature regarding RTW after “general” cervical degenerative myelopathy12,26, and in our current study, age and preoperative neurological symptoms appear to be consistently the factors most influencing RTW after cervical spine surgery. Furthermore, the results of this study revealed that postoperative residual NeP after c-OPLL surgery is one of the independent factors that affects postoperative RTW. It has been reported that age and preoperative neurological symptoms have a significant impact on postoperative residual NeP21,22. Taking all these results into account, if one of the goals after c-OPLL surgery is RTW, it may be advisable to consider surgical treatment at a younger age before neurological symptoms worsen. To prove this, a further study with a larger number of cases and consistent backgrounds is needed.

Otherwise, several limitations of this study must be noted. First, the number of cases is limited. However, this is the first nationwide multicenter study on RTW after surgery for c-OPLL. We believe that this study, which involves nationwide participation from facilities primarily involved in the treatment of this disease, ensures a relatively representative sample and reduces bias from a single institution. Second, this survey was conducted in the form of a questionnaire only among postoperative patients with c-OPLL and did not include non-surgical control cases. In addition, the survey items were limited. It is possible that the RTW rate was calculated lower than the actual rate because it was not possible to confirm whether or not patients had the intention to return to work after surgery. Many patients undergoing surgery for c-OPLL are at the same age as the retirement age, and therefore may retire after surgery without wishing to return to work, regardless of the treatment outcome. In addition, it has also not been confirmed whether there is any workers’ compensation, which is shown to affect RTW after surgery. However, the RTW rate in this study was 76.3%, which is not low compared to cervical degenerative diseases other than c-OPLL, and even if these effects existed, they were thought to be limited. Third, in this multicenter study, surgical procedures were selected by each center and were not randomized, which may have had some influence on the association between surgical procedure and RTW. Finally, postoperative JOA score, preoperative JOACMEQ, and the presence or absence of perioperative complications were not investigated in this study. These investigations, if possible, would allow for a more detailed assessment and should be investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, this first nationwide multicenter study revealed that postoperative residual NeP was a significant independent factor associated with RTW after c-OPLL surgery. Our immediate challenge is to establish a treatment for postoperative residual pain, including NeP. The results of this study will provide useful information for determining future treatment plans for patients with a view to returning to work after c-OPLL surgery, and may also have an impact on the indications for surgery for this disease.

Patients and methods

Participants

This nationwide, multicenter study involved 13 academic institutions of the Japanese Multicenter Research Organization for Ossification of the Spinal Ligament (JOSL) formed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). We conducted a questionnaire survey to investigate the status of RTW after surgery for c-OPLL. The protocol for this study has been approved by institutional review board (IRB) of Kitasato University as a Central IRB and the other all participating institutions including Shiga University of Medical Science as a local participating institution. This research was conducted in accordance with the “Declaration of Helsinki” and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare / Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology “Ethical Guidelines for Medical Research for Humans”. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

This study included patients who underwent surgical treatment for c-OPLL at participating institutions between 2014 and 2017 and were followed up for at least one year after surgery. A total of 286 patients (205 males and 81 females; average age 63.8 ± 10.7 years) who underwent surgery for myelopathy due to c-OPLL were enrolled from involved 13 institutions. Surgical procedures were selected by each participating institution and were not randomized. The surgical procedures performed were LMP, PDF, ADF, and AP combined. Patients who were unemployed before surgery were excluded from the study, but patients who were employed before surgery were not excluded because of age. Thus, 198 patients (160 males, 38 females, mean age at the time of surgery: 61.2 ± 10.8 years) with cervical myelopathy due to c-OPLL who were employed preoperatively were enrolled (Fig. 2).

Occupations were classified into four categories: unemployed, light sedentary labor, light standing labor, and heavy labor, according to the previous study11. Those who were able to return to work, regardless of whether they were in their original occupations or had changed occupations, were defined as having RTW. Employment style (full- or part-time employment), preoperative workload, and timing of RTW were also collected. Preoperative workload was assessed by the patients themselves as a percentage, with the state before the onset of symptoms being set at 100%. The patient demographics were collected from each patient, including age at the time of surgery, preoperative disease duration, gender, BMI, comorbidities, history of spine surgery of other sites.

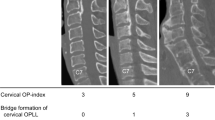

Radiographical assessments

K-line, that is a straight line connecting the midpoints of the spinal canals of C2 and C7 in the lateral radiograph were determined on a lateral standard radiograph of the cervical spine in the neutral position29. Patients were considered K-line—if OPLL crossed the K-line, and K-line + otherwise. The most compressed level and the presence of a signal intensity change in the spinal cord were investigated on T2-weighted MR imaging. In addition, COR of OPLL on axial computed tomography (CT) at the maximum cord compression level was investigated.

Clinical assessments

The preoperative clinical condition of the participants was determined using JOA score for cervical myelopathy30. The JOA score is a tool used worldwide to assess function in cervical myelopathy, and assigns points based on assessments of motor function, sensory function, and bladder function, with a range of 0 (minimum) to 17 points (maximum). Postoperative JOACMEQ was used for patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)31. JOACMEQ is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 24 questions addressing five domains: cervical spine function (Q1), upper limb function (Q2), lower limb function (Q3), bladder function (Q4), and QOL (Q5). In JOACMEQ, pain or stiffness in neck or shoulders, tightness in chest, pain or numbness in arms or hands, and pain or numbness from chest to toe were evaluated by VAS. In the present study, we used the PDQ as PROMs to assess postoperative residual NeP32. The PDQ categorizes scores of 13–18 as “unclear” and scores of 19 or higher as “positive” for NeP. A classification of “uncertain” suggests that there is an equivocal but inclusive presence of NeP, whereas “positive” indicates a greater than 90% probability of NeP. In this study, according to previous reports22, a score of 13 or greater on the PDQ was defined as NeP.

Statistical analyses

To assess the statistical differences between the RTW + and RTW—groups, we used the t-test for continuous variables. In the JOACMEQ analysis, the Mann-Whiteny U test was used in accordance with the recommendation of the JOA. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A P value below 0.05 was used as criterion for statistically significant difference. To elucidate the associated factors for success in achieving postoperative RTW, we employed multivariate logistic analysis. In the present study, we focused particularly on postoperative residual NeP and examined its influence using multivariate analysis, along with age, gender, and variables with significant univariate associations such as BMI, preoperative JOA score, and preoperative workload. Data in the present study are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the curves of the cumulative RTW rate. The software application used for the analysis was SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Kaplan–Meier curve graph was created using the statistical software R (Version 4.5.0., R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Key, G. A. On paraplegia depending on the ligament of the spine. Guy Hosp. Rep. 638, 17–34 (1838).

Kawaguchi, Y. et al. Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) clinical practice guidelines on the management of ossification of the spinal ligament, 2019. J. Orthop. Sci. 26, 1–45 (2021).

Nakashima, H. et al. Prediction of outcome following surgical treatment of cervical myelopathy based on features of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A systematic review. JBJS Rev. 28, e5 (2017).

Devin, C. J. et al. A predictive model and nomogram for predicting return to work at 3 months after cervical spine surgery: an analysis from the quality outcomes database. Neurosurg. Focus 45, E9 (2018).

Evans, T. H., Mayer, T. G. & Gatchel, R. J. Recurrent disabling work-related spinal disorders after prior injury claims in a chronic low back pain population. Spine J. 1, 183–189 (2001).

Nikolaidis, I., Fouyas, I. P., Sandercock, P. A. & Statham, P. F. Surgery for cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD001466 (2010).

Matsunaga, S. et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1, 494–498 (2001).

Lønne, V. V. et al. Return to work after surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy: a nationwide registry-based observational study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 165, 779–787 (2023).

Bhandari, M., Louw, D. & Reddy, K. Predictors of return to work after anterior cervical discectomy. J. Spinal Disord. 12, 94–98 (1999).

Faour, M. et al. Return to work rates after single-level cervical fusion for degenerative disc disease compared with fusion for radiculopathy in a workers’ compensation setting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 41, 1160–1166 (2016).

Kamizono, J. et al. Occupational recovery after open-door type laminoplasty for patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15, 1889–1892 (2003).

Romagna, A. et al. Factors associated with return to work after surgery for degenerative cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Cohort analysis from the Canadian spine outcomes and research network. Glob. Spine J. 12, 573–578 (2022).

Goh, G. S. et al. Poorer preoperative function leads to delayed return to work after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for degenerative cervical myelopathy. Int. J. Spine Surg. 15, 1184–1191 (2021).

Koda, M. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior decompression with instrumented fusion, and anterior decompression with fusion for K-line (-) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Eur. Spine J. 25, 2294–2301 (2016).

Nakashima, H. et al. Comparison of laminoplasty and posterior fusion surgery for cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament. Sci. Rep. 14, 748 (2022).

Yoshii, T. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior decompression with fusion and posterior laminoplasty for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J. Orthop. Sci. 25, 58–65 (2020).

Egawa, S. et al. Prospective investigation of postoperative complications in anterior decompression with fusion for severe cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A multi-institutional study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1, 1621–1629 (2021).

Nagoshi, N. et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes of anterior and posterior fusion surgeries for K-line (-) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A prospective multicenter study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1, 937–943 (2023).

Koda, M. et al. Neurological improvement is associated with neck pain attenuation after surgery for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Sci. Rep. 7, 11910 (2021).

Koda, M. et al. Factors significantly associated with postoperative neck pain deterioration after surgery for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Study of a cohort using a prospective registry. J. Clin. Med. 28, 5026 (2021).

Miyagi, M. et al. Residual neuropathic pain in postoperative patients with cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament. Clin. Spine Surg. 1, E277–E282 (2023).

Ikeda, S. et al. Risk factors for residual neuropathic pain using specific screening tools in postoperative patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. Eur. Spine J. 34, 2239–2246 (2025).

Yang, M. M. H., Far, R., Riva-Cambrin, J., Sajobi, T. T. & Casha, S. Poor postoperative pain control is associated with poor long-term patient-reported outcomes after elective spine surgery: an observational cohort study. Spine J. 24, 1615–1624 (2024).

Moisset, X. Neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Presse Med. 53, 104232 (2024).

Fehlings, M. G. et al. A Clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: Recommendations for patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease and nonmyelopathic patients with evidence of cord compression. Global Spine J. 7, 70S-83S (2017).

Fasinella, M. R., Benato, A., Creatura, D., Morgado, A. & Barrey, C. Y. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: timing of surgery. EFORT Open Rev. 2, 403–415 (2025).

Katsumi, K. et al. Natural history of the ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament: a three dimensional analysis. Int. Orthop. 42, 835–842 (2018).

Chikuda, H. et al. Acute cervical spinal cord injury complicated by preexisting ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a multicenter study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15, 1453–1458 (2011).

Fujiyoshi, T. et al. A new concept for making decisions regarding the surgical approach for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: the K-line. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15, E990-993 (2008).

Yonenobu, K., Abumi, K., Nagata, K., Taketomi, E. & Ueyama, K. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the Japanese orthopaedic association scoring system for evaluation of cervical compression myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1, 1890–1894 (2001).

Fukui, M. et al. Japanese orthopaedic association cervical myelopathy evaluation questionnaire: part 3. Determination of reliability. J. Orthop. Sci. 12, 321–326 (2007).

Freynhagen, R., Baron, R., Gockel, U. & Tölle, T. R. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 22, 1911–1920 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) and Health and Labour Science Research Grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M., M.M., Hir. N., H.T., S.Im., T.Y., M.K., and Y.K. contributed to planning and conduct of the present study and to reporting the present manuscript. K.M., K.S., K.K., S.M., T.H., M.M., S.Ik., M.K., S.Im. and M.Y. contributed to conception and design of the present study and to reporting the present study. S.Ik., Y.Y., K.S., T.E., M.T., S.T., S.K., S.E., T.H., S.M, T.H., N.N., Hir.N., Hid.N., K.K. contributed to conducting the present study and to editing the present manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. T.Y. supervised all the statistical analyses in the present study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board

This study was approved by each institutional review board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mori, K., Miyagi, M., Ikeda, S. et al. Postoperative residual neuropathic pain prevents return to work after cervical OPLL surgery: nationwide multicenter study. Sci Rep 15, 42724 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26781-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26781-9