Abstract

Young children are a high-risk group for dental caries. Understanding the prevalence, characteristics of severe early childhood caries (S-ECC), and its associated complications (e.g., pulpitis and periapical periodontitis) is crucial for guiding the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these conditions. A retrospective analysis was conducted on the dental records of children with S-ECC who received treatment at Jinan Stomatological Hospital from 2018 to 2023. Cases were excluded if they did not meet the S-ECC diagnostic criteria, had intellectual impairment, had other severe systemic diseases with unstable conditions, were duplicate records, or had missing critical data. Data processing was conducted using Python software. Among the 2,357 included 0–5-year-olds with a total of 26,215 primary teeth, 2–3-year-olds were the largest group (34.0%). Primary caries distribution: maxillary molars > mandibular molars > maxillary incisors > maxillary canines > mandibular canines > mandibular incisors. Notably, maxillary incisors had significantly higher rates of deep caries, pulpitis, and periapical periodontitis than other teeth (p < 0.05), showing faster disease progression. This study elucidates the epidemiological characteristics of S-ECC, laying a foundation for targeted prevention and clinical management in high-risk pediatric populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dental caries, a bacterial-driven multifactorial disease, is the most prevalent chronic condition among children, with an estimated 180 million new cases worldwide annually1. According to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated) lesions, missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth of a child under six years old. Severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) is characterized by more extensive decay: specifically, any sign of smooth-surface caries in children younger than 3 years, and for 3–5-year-olds, one or more smooth-surface cavitated lesions or a dmfs (decayed, missing due to caries, filled surfaces) score of ≥ 4 (for 3-year-olds), ≥ 5 (for 4-year-olds), or ≥ 6 (for 5-year-olds). The dmfs index quantifies caries burden by counting each affected tooth surface (e.g., a single molar with occlusal and proximal decay counts as 2 surfaces)2.

Data from the Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey show that the prevalence of primary tooth caries in 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children is 50.8%, 63.6%, and 71.9%, respectively, while the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) indices for these age groups are 2.28, 3.40, and 4.243. Although national estimates of S-ECC prevalence vary, regional studies and expert consensus indicate it affects a substantial minority of children but accounts for most severe pediatric dental complications4—a concern echoed by international health bodies5.

Dental caries remains a major public health issue, especially for children. Periapical inflammation from primary tooth caries can impair permanent tooth enamel development, cause enamel hypoplasia (thin, pitted enamel) in permanent teeth, and lead to premature or delayed eruption. These abnormalities disrupt the normal spacing of the permanent dentition, resulting in malocclusion (e.g., crowding, overbite). In severe cases, masticatory efficiency may decrease by 30–50% compared with that of children with healthy primary teeth, compromising nutritional intake (especially of harder foods like apples or carrots) and hindering overall growth and development6. Furthermore, childhood dental caries has been linked to negative psychological effects (e.g., anxiety, low self-esteem)7. For S-ECC, harm extends beyond this: its extensive lesions and rapid progression often cause periapical inflammation that affects multiple permanent tooth germs simultaneously.

This study analyzes medical records of children with S-ECC to clarify its epidemiological characteristics, thereby laying a foundation for targeted prevention strategies. Specifically, it aims to achieve two objectives: first, to characterize S-ECC’s epidemiological features, including age and gender distribution, site-specific primary tooth caries patterns, and progression trends; second, to explore differences in the distribution of S-ECC-related conditions (superficial caries, intermediate caries, deep caries, pulpitis, periapical periodontitis) across primary teeth.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective observational study, preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) prior to manuscript submission (Registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.io/CZDTK). The protocol prespecified the study design, outcome measures (e.g., caries depth distribution, pulpitis incidence), and statistical methods (chi-square test, logistic regression) to ensure transparency and avoid reporting bias. Temporally and geographically, this study included cases from 2018 to 2023 at Jinan Stomatological Hospital, with data spanning all seasons to minimize seasonal bias. Local records confirmed no large-scale childhood caries public health campaigns in Jinan during this period, eliminating intervention-related confounding. This aligns with clinical criteria for general anesthesia (GA) in pediatric dentistry, focusing on S-ECC that impairs oral function and requires urgent intervention8. Due to the retrospective nature of electronic medical records, systematic documentation of “teeth extracted specifically due to caries” was incomplete. Thus, caries burden was evaluated using available indicators: decayed teeth (d, defined as cavitated lesions confirmed clinically) and filled teeth (f, defined as restored teeth recorded in medical records), i.e., the df index. This approach ensures transparency in data usage, with clear definitions of d and f to maintain within-study comparability.

This study strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinan Stomatological Hospital (Approval No. JNSKQYY-2022-022).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

This study enrolled 0–5-year-old children who underwent dental treatment under GA at Jinan Stomatological Hospital from 2018 to 2023, met the AAPD (2017) S-ECC criteria, and had complete electronic medical records. S-ECC was diagnosed as: any smooth-surface caries in children < 3 years; or an age-specific dmfs index of ≥ 4 (for 3 years), ≥ 5 (for 4 years), or ≥ 6 (for 5 years) for children aged 3–5.

Exclusion criteria

Cases were excluded if they met any of the following: age > 6 years; failure to meet S-ECC diagnostic criteria; intellectual impairment or other severe systemic diseases; duplicate medical records (verified via HIS logs); or missing critical data (age, gender, dmfs index, or diagnostic details).

Data collection and cleaning

From the hospital’s medical records, 18,279 initial cases were identified. To protect patient privacy and data confidentiality, medical records were anonymized by removing personal identifiers (e.g., name, ID number) before data analysis.

Subsequent data cleaning and quality control were performed as follows: Python 3.8 was used for standardized data cleaning, unifying key fields (age, gender, tooth number, dental conditions) across 2018–2023 records. For cases with updated consultation card numbers, hospital information system (HIS) logs were used to trace associations and merge records, eliminating redundancies. Python 3.8 scripts checked the completeness of critical variables; cases with missing values in any critical variable were excluded to avoid bias in evaluating caries distribution and disease progression.

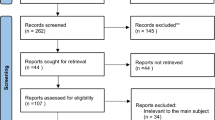

After screening, the final dataset (n = 2,357) had no missing data. Details of missing data screening criteria are documented in the OSF preregistration protocol (DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.io/CZDTK) (Fig. 1).

Patient screening flowchart. Initial cases identified from hospital medical records: n = 18,279; excluded cases: age > 6 years, non-S-ECC diagnosis, duplicate medical records, incomplete critical data (e.g., age, gender), and patients with unstable systemic conditions; final included cases: n = 2,357.

Diagnostic consistency control

Two measures were implemented to minimize inter- and intra-rater variability in diagnosis:

-

1.

Unified Diagnostic Criteria and Pre-Study Training: All oral disease diagnoses followed the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) criteria. Targeted training was provided once before study initiation and annually thereafter to unify diagnostic standards for conditions such as pulpitis and periapical periodontitis.

-

2.

Strict Dentist Qualifications: Only chief physicians and associate chief physicians with ≥ 10 years of clinical experience in pediatric dentistry were involved in diagnosis. Junior dentists were excluded to eliminate diagnostic variability from personnel.

Statistical analyses

Data processing and analysis were conducted in Python 3.8 using the following packages: pandas (v1.4.2) for data cleaning and standardization; scipy.stats (v1.8.0) for chi-square tests and Cramer’s V; statsmodels (v0.13.2) for logistic regression with Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)/Durbin-Watson diagnostics; numpy (v1.22.3) for frequency statistics and confidence intervals; and matplotlib (v3.5.1) for visualizations (Figs. 2 and 3).

Chi-square tests—verified for applicability (all expected cell frequencies > 5)—were used to analyze distributional associations of categorical variables, characterize epidemiological patterns across tooth positions (Tables 1 and 2), and quantify association strength via Cramer’s V. Logistic regression evaluated disease outcome risks (e.g., periapical periodontitis by tooth position), with key assumptions confirmed: no significant multicollinearity (all VIFs < 10) and no correlated residuals (Durbin-Watson = 1.92, near 2). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) revealed a significantly higher risk of disease progression to periapical periodontitis in maxillary central incisors relative to canines. Analyses focused exclusively on the primary dentition. This study also adhered to principles of patient privacy protection and data security.

Results

General information

Among the 2,357 cases, 1,352 (57.36%) were male and 1,005 (42.64%) were female. Patients aged 0–5 years had a mean age of 2.84 years, with the 2–3-year-old group accounting for the highest proportion of S-ECC cases (34.0%). A statistically significant discrepancy in gender distribution was observed across all age groups (p < 0.05). No AAPD-defined “special care patients” were included (n = 0), as these individuals either had unstable systemic conditions or did not meet the S-ECC criteria requiring GA (Fig. 2).

Diseases of primary teeth

Caries is progressive (from deep caries to pulpitis to periapical periodontitis); the following reflects the stages of the same pathological process, not independent conditions. Caries were classified into superficial, intermediate, and deep according to the Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey criteria10: superficial (enamel-limited, no dentin involvement or symptoms); intermediate (superficial dentin involvement, visible cavities, mild cold sensitivity); deep (deep dentin, near pulp without perforation, obvious temperature and mechanical sensitivity).

The distribution of superficial, intermediate, and deep caries across primary tooth types is detailed in Table 1. Maxillary primary molars were the most frequently affected by caries (31.29%), followed by mandibular primary molars (22.64%), maxillary primary incisors (16.93%), maxillary primary canines (13.94%), mandibular primary canines (8.25%), and mandibular primary incisors (6.95%). Additionally, the mean number of teeth with superficial or intermediate caries was significantly lower than that with deep caries (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Among diseased primary teeth:

-

1.

The primary mandibular first molars were the most affected (n = 3,653), while the primary mandibular central incisors were the least (n = 567);

-

2.

Progressive stages of caries varied significantly by tooth position (p < 0.05): Primary maxillary central incisors exhibited all three stages (caries → pulpitis → periapical periodontitis), indicating faster disease progression;

-

3.

Disease type distribution differed significantly between maxillary central incisors and canines. Among diseased primary maxillary central incisors, periapical periodontitis was the most prevalent (44.22%), followed by caries (29.90%) and pulpitis (25.88%). In stark contrast, caries were the overwhelming majority among diseased primary maxillary canines (81.23%), with much lower rates of pulpitis (15.44%) and periapical periodontitis (3.33%).

Logistic regression corroborated this pattern, showing that the risk of progressing to periapical periodontitis was 23.0 times higher in maxillary central incisors than in maxillary canines (OR = 23.0; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 18.4–28.7; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

From the line graph illustrating disease type distribution across primary tooth types (Fig. 3):

-

1.

Maxillary primary molars had 4,420 cases of deep caries, 1,492 of pulpitis, and 866 of periapical periodontitis (ratio: 1:0.34:0.20);

-

2.

Maxillary primary canines had 1,947 cases of deep caries, 403 of pulpitis, and 87 of periapical periodontitis (ratio: 1:0.21:0.04);

-

3.

In contrast, disease distribution in maxillary primary incisors was more balanced: 2,457 cases of deep caries, 1,881 of pulpitis, and 2,169 of periapical periodontitis (ratio: 1:0.77:0.88).

Discussions

Dental caries remains a major global public health concern, and children are particularly vulnerable to the onset and progression of this chronic oral disease. Our GA-treated S-ECC cohort was selected in this study for two primary reasons: First, extensive lesions (e.g., multi-tooth deep caries) made sequential treatment under local anesthesia impractical11; Second, severe non-compliance—such as in children < 3 years old unable to tolerate local anesthesia due to fear or restlessness—was a key determining factor12. Compared with mild-to-moderate ECC cases treated under local anesthesia, this subgroup better reflects the core features of severe S-ECC, including caries burden, site-specific progression, and associated complications.

This study found the 2–3-year-old group had the highest proportion of S-ECC cases, consistent with the typical onset peak of S-ECC (1–3 years) reported in previous studies9. Regarding the distribution of caries in primary teeth, two key patterns emerged: First, maxillary and mandibular primary molars were the most affected (maxillary primary molars: 31.29% of carious teeth; mandibular primary molars: 22.64%), followed by maxillary primary incisors (16.93%); Second, the maxillary arch—especially maxillary primary incisors—exhibited the fastest disease progression: among diseased maxillary central incisors, periapical periodontitis was the most prevalent (44.22%), and logistic regression confirmed their risk of progressing to periapical periodontitis was 23.0 times higher than that of maxillary primary canines (OR = 23.0; 95% CI = 18.4–28.7; p < 0.001).

From an anatomical and clinical perspective, the high caries prevalence in maxillary and mandibular primary molars likely stems from jaw development, which creates interdental gaps that increase food impaction and reduce cleaning efficiency. Additionally, these posterior teeth are difficult for parents to examine—due to children’s poor compliance and limited visualization—so maxillary canines can serve as an indicator: non-traumatic darkening or defects in maxillary canines signal a higher risk of posterior caries, requiring timely professional evaluation.

For the rapid progression of maxillary central incisors, potential reasons include: occult early adjacent caries (easily overlooked in early stages), thick root canals, and high blood perfusion—all of which accelerate the spread of infection from caries to pulp and periapical tissues. In contrast, maxillary primary canines (which have high caries prevalence but low risk of pulpitis or periapical periodontitis) benefit from groove-rich morphology (increasing caries susceptibility but limiting infection spread), narrow mineralized pulp cavities, and thick incisal enamel—highlighting the need for early intervention once caries are detected9. Notably, untreated infection in maxillary central incisors may damage permanent tooth buds, underscoring the importance of parental monitoring and regular dental check-ups.

Therefore, effective S-ECC prevention strategies for children aged 0–5 years should include the following targeted measures: First, early intervention: using a finger toothbrush once the first primary tooth erupts and stopping night feeding by 1 year of age to reduce the risk of “bottle caries"9; Second, standardized topical fluoride application in accordance with WHO guidelines: topical fluoride has been proven to reduce the incidence of ECC by 40%17; Third, enhanced parental education: addressing common misconceptions (e.g., “primary teeth do not require treatment”), promoting biannual dental check-ups, and emphasizing monitoring of maxillary central incisors (to detect rapid caries progression early)—all to enable timely intervention13.

Some limitations of this study cannot be ignored. First, its retrospective design limits causal inference, and key confounders such as socioeconomic status13, fluoride exposure14,15 and feeding patterns16 were unanalyzed due to incomplete electronic records; Second, the cohort exclusively comprises severe S-ECC cases, potentially overestimating the severity of ECC in the population aged 0–5 years8; Third, the reliance on data from a single institution limits the generalizability of our findings, as unevaluated factors may vary elsewhere; Fourth, the lack of long-term follow-up prevents assessment of the dental impacts of GA. Future prospective studies should address these issues by establishing multi-institutional cohorts, including mild-to-moderate cases, systematically collecting data on confounders, and incorporating long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

Based on data from 0–5-year-old children with severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) who received dental treatment under GA at Jinan Stomatological Hospital between 2018 and 2023, this study provides critical age-specific epidemiological evidence for the clinical management of S-ECC. The findings reveal that while caries were most prevalent in primary molars, maxillary primary incisors exhibited the fastest disease progression—with an extremely high risk of progressing to periapical periodontitis (odds ratio [OR] = 23.0; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 18.4–28.7). This highlights the urgent need for specialized preventive strategies targeting this age group, including cessation of night feeding, early application of topical fluoride, and enhanced parental education. Collectively, these findings underscore the value of a comprehensive, targeted approach to preventing and managing S-ECC in this vulnerable pediatric population.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and available from the corresponding author.

References

Krol, D. M. & Whelan, K. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics 151 (1), e2022060417 (2023).

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr. Dent. 39, 59–61 (2017).

Du, M. Q. et al. Dental caries status and its associated factors among 3- to 5-Year-Old children in china: A National survey. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 21, 167–179 (2018).

Lam, P. P. Y., Chua, H., Ekambaram, M., Lo, E. C. M. & Yiu, C. K. Y. Risk predictors of early childhood caries Increment-a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Evid. -Based Dent. Pract. 22, 101732 (2022).

International Association of Pediatric Dentistry (IAPD). Early childhood caries: IAPD Bangkok declaration. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 41, 384–386 (2019).

Mathur, V. P. & Dhillon, J. K. Dental caries: A disease which needs attention. Indian J. Pediatr. 85, 202–206 (2018).

Shokravi, M., Khani-Varzgan, F., Asghari-Jafarabadi, M., Erfanparast, L. & Shokrvash, B. The Impact of Child Dental Caries and the Associated Factors on Child and Family Quality of Life. Int. J. Dent. 4335796 (2023).

Chinese Stomatological Association. [Guideline on the use of general anesthesia for pediatric dentistry dental Procedure]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 56, 231–237 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Expert consensus on early childhood caries management. Int. J. Oral Sci. 14, 35 (2022).

Lu, H. X. et al. The 4th National oral health survey in the Mainland of china: background and methodology. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 21, 161–165 (2018).

Burgette, J. M. & Quinonez, R. B. Cost-Effectiveness of treating severe childhood caries under general anesthesia versus conscious sedation. Jdr Clin. Transl Res. 3, 336–345 (2018).

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). General Anesthesia and Deep Sedation for Dental Treatments in Children: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines. (Ottawa (ON)), (2017).

Al-Jaber, A. S., Al-Qatami, H. M. & Jawad, A. A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and practices of parents on early childhood caries in Qatar-A questionnaire study. Eur. J. Dent. 16, 669–679 (2022).

Whelton, H. P., Spencer, A. J., Do, L. G. & Rugg-Gunn, A. J. Fluoride revolution and dental caries: evolution of policies for global use. J. Dent. Res. 98, 837–846 (2019).

Schmoeckel, J., Gorseta, K., Splieth, C. H. & Juric, H. How to intervene in the caries process: early childhood caries - A systematic review. Caries Res. 54, 102–112 (2020).

Wong, H. M. Childhood caries management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 8527 (2022).

Jain, N., Dutt, U., Radenkov, I. & Jain, S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: Actions, discussion and implementation. Oral Dis. 30, 73–79 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by Jinan Medical and Health Science and Technology Big Data Development Plan (2022-BD-15,2022-YBD-17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xuan Wen and Changjie Xiao carried out the study and drafted the manuscript. Xuan Wen and Xijiao Yu performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Ao Lv and Xiaonan Yu participated in collecting and acquiring data. Xijiao Yu, Lixia Zhang, and Yi Du participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinan Stomatological Hospital on November 15, 2022 (Approval No.: JNSKQYY-2022-022), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, X., Xiao, C., Lv, A. et al. Study of severe early childhood caries in children under general anesthesia from a single hospital. Sci Rep 15, 42699 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26786-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26786-4