Abstract

Wildfires are a critical global threat, necessitating advanced early detection and monitoring systems. This research introduces a novel multi-modal framework that integrates wide-area Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for all-weather surveillance with high-resolution UAV-based optical and thermal imagery for precise analysis. The proposed hybrid learning framework utilizes FPANet, a Vision Transformer-based architecture that captures both local textures and global spatial dependencies to achieve robust segmentation from SAR data under cloudy or smoky conditions. For fine-grained analysis, the system employs DualSegFormer, a model designed for the synergistic multi-modal fusion of thermal and RGB UAV images, ensuring high-fidelity fire front delineation even when visibility is compromised. Additionally, a Vision-Language Model (VLM) is integrated to translate complex sensor data into actionable, human-readable insights for effective disaster response. Experimental results demonstrate a significant improvement over conventional methods: the SAR-based FPANet achieves an F1-score of 0.830 and an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.750, the UAV-based DualSegFormer attains a superior F1-score of 0.946, and the VLM component shows strong semantic alignment with a BERTScore of 0.953. These results confirm the ability of the proposed hybrid learning approach to provide more effective and reliable wildfire monitoring, thereby advancing ecosystem resilience and facilitating timely disaster response in alignment with international SDG initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wildfires pose a significant environmental concern, affecting ecosystems, communities, and economies worldwide. Climate change and changes in land use practices are the main factors contributing to the increased frequency and intensity. This signifies a need for enhanced monitoring methods and early warning systems. Optical and thermal imaging have historically demonstrated effectiveness in fire monitoring, commonly employed on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). These methods yield real-time, high-resolution data on fire propagation. Adverse weather conditions, including darkness, cloudiness, and smoke, hinder the effectiveness of these sensors, which raises concerns during essential detection periods. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) offers significant advantages, including the capability to penetrate obstacles and operate efficiently in diverse weather conditions. The method exhibits limitations, such as diminished spectral resolution and an increased complexity in the analysis of backscatter.

This research aims to develop and evaluate a hybrid system for wildfire detection utilising Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data alongside high-resolution RGB and thermal imagery obtained from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). This system utilises Synthetic Aperture Radar technology to detect fires across extensive areas, irrespective of weather conditions. Utilising accurate data from UAVs, it produces detailed maps of the fire front and assesses the severity of the burn. This study aligns with the objectives of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15, particularly targets 15.1, 15.2, and 15.3, as it establishes a more reliable and efficient system applicable in various contexts. This will protect terrestrial ecosystems, promote sustainable forestry practices, and prevent land degradation.

This research outlines the creation and evaluation of a novel approach for the early identification of wildfires. SAR data is integrated with high-quality, detailed, regular, and thermal drone imagery. This combination yields a fire monitoring tool that demonstrates enhanced reliability and effectiveness across various terrains. Ultimately, this goes beyond just technology; it signifies a major step forward in protecting life on Earth and advancing Sustainable Development Goal 15. This research presents several significant contributions:

-

A Novel Multi-Modal Fusion Framework: This study introduces a unified framework that leverages the extensive detection capabilities of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) across various weather conditions, while incorporating detailed data from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for precise fire front mapping and burn severity evaluation.

-

Specialized Deep Learning Architectures: This work proposes the hybrid approach of the proposed FPANet and Enhanced DualSegFormer networks.

-

FPANet: A Vision Transformer-based network optimised for segmenting wildfires in noisy SAR data, effectively capturing local textures and global spatial dependencies.

-

Enhanced DualSegFormer: A model has been developed for the efficient and flexible integration and segmentation of UAV-based thermal and RGB imagery, ensuring precise delineation in low visibility conditions.

-

-

Integration of a vision-language model (VLM): this is essential for advancing multimodal understanding. The framework incorporates a VLM component that transforms intricate sensor data and temporal variations into actionable insights, thereby linking raw pixel-level detection with efficient, data-driven disaster response.

Related works

Wildfires are a significant and escalating global issue that necessitates advanced research in their prediction, detection, and management. In this section, we present a comparative analysis of recent research that has examined a variety of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning models that are employed for wildfire-related tasks. We evaluate the strengths, shortcomings, and practical utility of each model.

Several studies emphasize ensemble models and data fusion to improve wildfire assessment. One such work introduces FuelVision1, an AI-based framework that integrates multi-spectral satellite imagery, SAR data, and terrain information using a combination of deep neural networks, decision trees, and gradient boosting. This approach enhances fuel mapping accuracy, particularly by incorporating synthetic datasets generated through AI-based augmentation. Another study2, takes a similar multimodal approach but applies it specifically to wildfire identification in Europe. However, instead of presenting a detailed architecture, it highlights key challenges such as data limitations and model interpretability. The use of ensemble methods and multi-modal data fusion3 clearly improves robustness and accuracy in wildfire analysis, yet the computational costs and complexity of aligning diverse data sources remain significant challenges.

The research conducted by Jonnalagadda et al. 20244 compares the efficiency of transfer learning in detecting wildfires by comparing custom-developed CNN models with pre-trained models, such as VGG-16, VGG-19, and ResNet101. Pre-trained models, particularly VGG-16, have improved accuracy by efficiently recognizing complex wildfire patterns; however, more basic custom models offer faster inference rates. This indicates a growing reliance on transfer learning for successful model training, although its effectiveness is heavily influenced by the similarity of the source and target datasets. Zhao et al.’s article 20235 offers a comprehensive examination of this methodology.

The study6 aims to predict wildfires by analyzing anomaly detection methods within the context of unsupervised learning. This study utilizes deep autoencoders and clustering techniques to predict wildfires by detecting anomalous patterns in historical weather and NDVI data, without the necessity of labeled data. The autoencoder utilizing reconstruction error demonstrated strong performance; however, clustering techniques exhibited significant sensitivity to hyperparameters, resulting in reduced reliability. The efficiency of unsupervised learning is evident in its utilization of readily accessible data; however, challenges arise from its reliance on parameter tuning and the complexities associated with validating identified anomalies. Another region of innovation is the improvement of the interpretability of SAR imagery through the fusion with multispectral optical data7. Shearlet transforms are used to maintain important spatial information and enhance the resolution of SAR images. This approach makes SAR data even more useful for monitoring conflagrations beyond what is achievable with traditional fusion methods in visual and statistical results. However, the use of these fusion methods in a practical setting can be limited by the possibility of spectral deformation and the need for large amounts of computational capabilities.

The study by Hanson et al. 20248 examines the use of hyperspectral and LiDAR data to evaluate wildfire risk, focusing on the creation of a vehicle-based data collection platform. While it establishes a framework for aligning and analyzing various datasets, it fails to deliver comprehensive results. Another study9 explores the use of spatial-temporal models for fire progression prediction. It compares pixel-based temporal models, 2D image-based spatial models, and 3D spatial-temporal architectures, concluding that integrating temporal information, as seen in 3D UNETR, slightly improves active fire detection. While capturing wildfire dynamics over time enhances prediction accuracy, training such models requires substantial computational resources and access to consistent remote sensing data, which is often difficult to obtain due to cloud cover and sensor limitations.

Following the integration of AI with UAVs and satellites, recent research has investigated edge computing architectures to provide real-time detection of wildfires. For example, in10, Allison et al. introduced an edge-computing system based on lightweight CNNs running on devices mounted on UAVs. Using MobileNetV3 combined with hardware accelerators such as Intel Movidius, the authors obtained sub-second inference times that allow for fire detection in real time without dependence on cloud connectivity. This method overcomes the latency issues identified in previous research, e.g., by Ansaf et al.5, while ensuring resource-constrained platform compatibility.

Similarly, Chen et al.11 proposed a federated learning framework for cooperative wildfire detection in distributed swarms of UAVs. Their approach allows unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to share model updates rather than raw sensor data, thus maintaining privacy and bandwidth. This is a critical development for large-scale deployment, such as is being contemplated by Tzoumas et al.12. Apart from the multisensor data fusion trends reported by Rashkovetsky et al.13, current research has focused on hybrid architectures combining recurrent networks and CNNs. For example10, improves detection robustness in dynamic fire spread scenarios by adding LSTM layers over a ResNet-50 backbone to process temporal sequences of thermal images from UAVs. For applications with intermittent occlusions of smoke, this dual modality proved better than the CNNs on its own, a drawback evidenced by Ghali et al.’s U-Net tests3. Concurrently11, also examines multimodal fusion of hyperspectral and LiDAR sensors by means of cross-attention transformers, seeing its fire edge demarcation 12

The challenge of limited labeled wildfire datasets, as raised in Zhu et al.14, has spurred advances in synthetic data generation. In11, Chen et al. employed a diffusion-based generative adversarial network (GAN) to synthesize high-fidelity wildfire images conditioned on meteorological parameters like wind speed and humidity. This method reduced the reliance on rare real-world fire events for training, complementing the weakly supervised annotation techniques discussed in earlier YOLOv5 implementations14. Similarly10, introduced a physics-informed GAN that simulates fire propagation patterns based on historical burn scar data, enabling models to generalize better to unseen environments–a critical step toward addressing the robustness gaps identified in Bouguettaya et al.’s work15.

The use of LLMs to analyze wildfire policies, as led by Gao et al.16, has become increasingly interactive. The system fills the gap between detection at the low level and impactful decision-making, resonating with the call for actionable insights outlined in Farraj and Jemaa’s analysis of UAV-IoT networks17. A summary of these diverse research contributions, highlighting their methodologies, data sources, strengths, and limitations, is presented in Table 1

Deep learning algorithms play a central role in modern wildfire detection. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are widely used in feature extraction in image-based fire detection, particularly in real-time applications18. The SegNet model by Jonnalagadda and Hashim highlights the advantages of optimized feature map reduction, which results in improved speed and accuracy. In tandem, object detection models such as the YOLO family have demonstrated remarkable performance for smoke and wildfire localization. Studies comparing YOLOv8, such as those conducted by Ramos et al.19,20, highlight hyperparameter optimization as a key factor in realizing superior detection accuracy. Recent studies have further investigated hybrid models that combine CNNs with transformers, allowing both fine-grained local feature extraction and wider contextual understanding21. For real-time monitoring in large-scale wildfire surveillance, UAV swarms have been suggested as a viable means of monitoring. Their deployment does, however, necessitate resilient decentralized control frameworks. Tzoumas et al.12 explored distributed algorithms for autonomous spatial coverage, where the Dynamic Space Partition (DSP) algorithm has been shown to be a potential method for wildfire localization and tracking. Concurrently, onboard processing capabilities are still essential for on-time threat analysis and response. Spiller et al.22 carried out a feasibility study on AI systems based on satellites, with a focus on the hardware accelerators’ role to facilitate instant inference and alerting.

Across these studies, several recurring challenges emerge, including the scarcity of labeled data, the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, and the difficulty of ensuring model robustness across diverse wildfire conditions. Many approaches attempt to integrate multiple data sources, but alignment issues and computational demands remain hurdles. Moreover, deep learning models tend to be “black boxes,” which makes it hard to interpret their predictions, an important consideration for real-world deployment in wildfire management. Nevertheless, the area is developing very fast, with progress in transformer-based architectures, graph neural networks, and UAV-based wildfire monitoring providing new directions for research. The movement towards the fusion of heterogeneous sensor data, along with advances in light and explainable AI models, is likely to fuel continued advances in wildfire prediction, detection, and control.

Data sources

This work builds wildfire detection and monitoring on an integrative data synergy approach. We strategically leverage the strengths of three disparate but highly complementary data sets: the FLAME 3 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) dataset, Landsat 8 and 9 satellite imagery, and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) data. This multi-disciplinary framework is intentionally designed to circumvent the inherent limitations that arise when utilizing a single data source for an exhaustive analysis of wildfires. The subsequent section provides a comprehensive examination of the unique characteristics of each dataset, defining the processing methods, and elucidating their specific responsibilities within the integrated analysis framework. The primary emphasis is on the synergistic interaction between these sources of data, which is the foundation of the proposed strategy to advance the science of wildfires.

FLAME 3 dataset

The Fire Luminosity Airborne-based Machine learning Evaluation (FLAME 3) dataset23, a new and influential addition to the world of aerial fire monitoring, appeared in December 2024. It provides painstakingly co-registered visual and radiometric thermal imagery, taken by controlled UAV flights during prescribed burn experiments. The genuine innovation of FLAME 3 lies in its ability for unparalleled thermal mapping fidelity. It provides per-pixel temperature readings of extraordinary precision, a feature of critical significance to perform finely detailed fire behavior analysis, with examples of the RGB, thermal, and fire mask data shown in Fig. 1.

This image showcases three different representations of wildfire data from the FLAME 3 dataset. The left image is an RGB aerial view capturing the fire and smoke, the middle image is a thermal representation highlighting high-temperature areas in bright yellow, and the right image is a fire mask that segments the fire-affected regions in high contrast.

The complete dataset contains 13,997 images collected from six distinct prescribed fire events across the United States. The geographic coverage is intentionally diverse to ensure model robustness, capturing a wide range of fire-prone ecosystems. These locations include the longleaf pine forests of Florida (Hanna Hammock), Ponderosa pine, grass, and sagebrush environments in Arizona (Hundred, Shoetank Rx, Wildbill), and oak woodlands and grasslands in Oregon (Sycan, Willamette Valley). This variety encapsulates diverse fuel types, burn behaviors, atmospheric conditions, and topographies, providing a rich collection of scenarios for training and validating wildfire management models.

The thermal information, saved in the robust radiometric Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) format, maintains the integrity of unprocessed temperature values, thus facilitating a range of strict quantitative analyses, from elaborate temperature gradient mapping to complex radiative heat flux computations. Captured over diversified flight trajectories in fire-prone areas, FLAME 3 encapsulates the dynamic temporal development and spatial heterogeneity of thermal signatures, at scales previously impossible with conventional satellite-borne platforms.

Held between 50 and 200 meters, the operational altitudes provide impressive ground sampling distances (GSDs) of approximately 5–20 cm for visual imagery and 15–60 cm for thermal imagery. For many of the key issues in wildfire science, this record spatial resolution is vital. It enables in-depth flame front analysis, allowing the complex characterization of fire behavior at high precision within the combustion zone itself. Additionally, it enables the identification of even subtle thermal anomalies–highlighting nascent patterns potentially leading to imminent fire spread, which may otherwise go undetected in coarser resolution data.

Most importantly, FLAME 3 provides a high-accuracy ground truth validation benchmark. It offers essential reference data to rigorously calibrate thermal retrievals derived from both Landsat and VIIRS, enhancing the overall reliability of satellite-derived fire products. Finally, as it originates from ethically conducted controlled burn experiments, FLAME 3 delivers high-fidelity data under precisely documented fire conditions, making it indispensable for developing and validating novel wildfire detection algorithms.

Landsat 8 & 9: landscape-scale multispectral and thermal satellite observations

The proposed analytical approach incorporates both multispectral and thermal infrared data sourced from the venerable Landsat program. Specifically, this work utilize imagery acquired by Landsat 8 and the more recent Landsat 9, operational since September 202124. Landsat’s long-standing record of systematic Earth observation, paired with its 16-day revisit cycle, furnishes crucial temporal context for understanding wildfire dynamics at the landscape scale, as illustrated by the satellite imagery and corresponding fire mask in Fig. 2.

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) delivers 30-meter spatial resolution across the visible and near-infrared (VNIR) spectrum. This is particularly useful for assessing post-fire burn severity and pre-fire vegetation conditions. The Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) captures 100-meter resolution thermal data–though coarser, it still helps identify general thermal anomalies and supports Land Surface Temperature (LST) estimation.

All Landsat data undergo rigorous pre-processing to ensure temporal comparability and accuracy. Atmospheric correction is conducted through the Landsat Ecosystem Disturbance Adaptive Processing System (LEDAPS), facilitating the retrieval of surface reflectance and enabling accurate computation of key vegetation indices, such as NDVI and dNBR.

A customised LST calibration method is implemented for the thermal bands to ensure radiometric consistency across observations, thereby facilitating the detection of subtle thermal anomalies associated with active or residual wildfire activity. The 30-meter multispectral data from Landsat is essential for numerous applications concerning wildfires. Evaluations of pre-fire fuel conditions employ vegetation indices derived from VNIR bands, providing insights into vegetation health and dryness, which are essential for predicting fire risk.

Additionally, post-fire burn severity mapping relies on Landsat’s capacity to assess fire effects on vegetation and soil through indices such as dNBR. This capability significantly enhances long-term ecological impact assessments and recovery monitoring. The broad synoptic view provided by Landsat imagery enhances the high-resolution yet spatially restricted coverage of UAV data, facilitating thorough delineation of fire extent across extensive geographic areas.

VIIRS: near real-time, wide-swath active fire monitoring

Acquired from the Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites, data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS)25delivers near real-time wildfire monitoring at scale. VIIRS features broad spectral coverage–22 bands spanning 0.412 to 12.01 \({\upmu }\)m–and notable thermal sensitivity, detecting active fire pixels with temperatures as low as 700 K against ambient backgrounds.

This study primarily employs the VIIRS 375-meter active fire product (VNP14IMG), which significantly improves upon earlier systems like MODIS in both resolution and sensitivity. With a swath width of 3,060 kilometers, VIIRS enables near-global coverage approximately every 12 hours, depending on latitude and satellite configuration.

In the proposed framework, VIIRS plays several crucial roles. It delivers real-time fire alerts and continuous monitoring of fire ignition and spread, supporting early warning systems and situational awareness during wildfire events. It also enables large-scale fire mapping, offering a synoptic view of fire distribution and spread patterns, an example of which is provided in Fig. 3.

Additionally, VIIRS helps track smoke plume dynamics using specialized aerosol-sensitive bands, providing key insights into air quality and aiding fire behavior forecasting. Its frequent revisit rate bridges the temporal gaps in Landsat’s 16-day cycle, ensuring high-frequency fire event monitoring that complements and enhances the temporal depth of the overall detection system.

This contrasts VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) satellite band image on the left with its matching fire mask (right). The left greyscale image depicts the terrain and elements connected to fire. By contrast, the fire mask on the right highlights red areas where fires have been discovered.

Sentinel-1: all-weather SAR surveillance

This work employs C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 mission to give us a strong detection system that works in any weather and is better than optical and thermal sensors26. The dual-satellite constellation has a big benefit since it can see through smoke, clouds, and darkness, which means that monitoring will always be accurate, no matter what the weather is like or what time of day it is. Its methodical gathering strategy delivers reliable data with a revisit duration of 6–12 days, which is useful for keeping an eye on changes in the terrain.

This research uses the Interferometric Wide Swath (IW) mode. This is how it works most of the time on land. The IW mode gives you data with two polarisations (VV and VH) and a spatial resolution of around 10 to 20 meters over a huge 250 km swath. This mix is great for finding burn scars and other changes in the surface structure and moisture content that happen during and after a fire. The radar backscatter is particularly sensitive to the changes that a fire brings to the land, such as taking away the plant canopy and making the soil rougher. This makes it easy to find burn scars on a map. Table 2 provides a comprehensive comparison of these data sources, summarizing their key features, strengths, and limitations.

Methodological overview

To address the challenges of modern wildfire monitoring, this work introduces a comprehensive, multi-modal detection and interpretation system. The proposed methodology is built on a synergistic framework that integrates broad-area satellite surveillance with targeted, high-resolution aerial imaging, culminating in an automated semantic analysis. This three-stage approach is designed to create a robust, end-to-end pipeline that transforms raw sensor data into actionable intelligence.

The workflow is structured in three different components and each component performs a crucial part of the work:

-

Component 1: Broad-Area Surveillance with SAR The first component employs FPANet for large-scale, continuous surveillance using SAR imagery. Leveraging SAR’s ability to penetrate smoke and clouds, this component provides a reliable, all-weather capability to detect potential fire hotspots over vast geographical areas.

-

Component 2: Targeted High-Resolution Analysis with UAVs Upon detection by the SAR system, UAVs equipped with RGB and thermal sensors are deployed for a targeted analysis. The improved DualSegFormer model intelligently fuses this multi-modal data to produce a precise, high-fidelity segmentation of the fire perimeter.

-

Component 3: Semantic Interpretation with Vision-Language Models In this Component, the segmentation masks generated by the first two components are fed into a Vision-Language Model (VLM). This model translates the raw pixel-level data and its temporal changes into human-readable, natural language summaries, providing critical insights into the fire’s behavior, growth, and threat level.

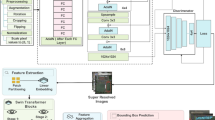

Together, these components form an integrated system that transitions from coarse detection to fine-grained analysis, and finally to semantic understanding. The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of the architecture and implementation of each component. The overall architecture of this integrated system is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Significance of proposed work

Identifying wildfires requires a robust and precise segmentation method capable of functioning across diverse environments. The proposed solution transcends the constraints of conventional single-modal systems by integrating Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) with UAV-based RGB-Thermal data. The primary technical challenge in segmenting wildfires lies in the variability of features due to smoke obstruction, alterations in lighting conditions, and shifts in the spectral range. We employ a modality-specific, trainable weight technique to automatically balance the contributions of RGB and temperature data. This adaptive fusion method ensures that segmentation does not prioritise one modality over another. This prevents performance degradation in low visibility conditions where thermal data is more reliable.

The proposed approach employs skip connections alongside multi-scale feature refinement to preserve small spatial features typically diminished during standard upsampling processes. Accurate definition of fire edges is essential. Intermediate supervision supports the reduction of error propagation across deeper layers. The architecture is optimised for computational efficiency. The system employs streamlined feature extraction blocks that eliminate superfluous processes, enabling real-time inferences with minimal latency on edge devices. A specialised loss function enforces fusion consistency between modalities, enhancing cross-modal learning, and mitigating overfitting to a single data source. The subsequent section discusses data preprocessing and the need for a fusion strategy between SAR and UAV data.

Data harmonization and preprocessing

To ensure the integrity and comparability of the multi-modal data streams, a rigorous and modality-specific preprocessing pipeline was established. This crucial stage transforms the raw sensor data into a harmonized, analysis-ready format suitable as input for the deep learning models.

For the high-resolution UAV imagery from the FLAME 3 dataset, we leveraged its inherent co-registration between the RGB and thermal sensors. The primary preprocessing step involved normalizing the pixel values of both modalities to a consistent range of [0, 1]. This scaling is essential for stabilizing gradient descent during the training of the DualSegFormer model and ensuring that neither data stream disproportionately influences the initial learning phase.

The satellite-derived datasets required more extensive harmonization to align them geographically and radiometrically. As previously noted, Landsat 8/9 imagery underwent atmospheric correction using the LEDAPS system to yield surface reflectance values, while the VIIRS active fire product (VNP14IMG) was utilized directly as a geolocated reference. For the Sentinel-1 SAR data, a standard workflow was implemented, comprising radiometric calibration to generate backscatter coefficients, speckle noise reduction using a Lee filter to enhance signal clarity, and Range-Doppler Terrain Correction for geometric accuracy. A critical step in this stage was the spatial co-registration of all satellite products. All datasets were reprojected to a common Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system to ensure precise pixel-level alignment, which is fundamental for the cueing mechanism between the SAR-based detection and targeted UAV analysis.

This comprehensive preprocessing framework ensures that each data source is cleaned, normalized, and spatially harmonized, creating analysis-ready inputs tailored to the specific requirements of the FPANet and DualSegFormer architectures.

Fusion strategy between SAR and UAV data

The fusion of SAR satellite data and UAV imagery in the proposed system is operational and sequential, not a direct pixel-level or feature-level fusion. This decision-level integration leverages the distinct strengths of each modality in a two-stage workflow:

-

1.

Initial Detection and Cueing (SAR): The FPANet model processes wide-area SAR data to provide a coarse, geo-referenced segmentation mask of potential fire activity. This output serves as a “region of interest” (ROI) proposal. The primary advantage here is SAR’s all-weather, 24/7 capability, ensuring that initial detection is not missed due to clouds, smoke, or darkness.

-

2.

Targeted Analysis and Refinement (UAV): The geo-coordinates of the ROI detected by the SAR system are used to direct the deployment of a UAV. The UAV then captures high-resolution RGB and thermal imagery of that specific, targeted area. The DualSegFormer model processes this data to generate a precise, high-fidelity fire perimeter mask.

Advantages of this Strategy: This approach is highly resource-efficient, as it avoids speculative UAV deployment over vast, fire-free areas. It combines the broad-area persistence of satellite SAR with the on-demand, high-resolution detail of UAVs, creating a scalable and effective monitoring system. The final situational awareness is derived from the high-detail UAV data, which is contextualized within the larger landscape view provided by SAR.

Component 1: SAR-based wildfire segmentation using FPANet

Architectural overview

The first part of the proposed system is the Vision Transformer-Based Feature Pyramid Attention Network (FPANet), which is designed to partition wildfires in Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images. Conventional deep learning techniques often struggle with the unique problems that SAR data presents, like speckle noise, low contrast, and complex backscatter patterns. This model solves these problems by combining a transformer-based feature extraction backbone with multi-scale attention methods. This makes a strong and accurate segmentation framework. This architecture is necessary for the multi-modal monitoring system because it allows for initial wide-area detection that guides later UAV-based analysis.The detailed architecture of the FPANet model is shown in Fig. 5.

Swin transformer backbone

The Swin Transformer is the main part of FPANet that extracts features. The Swin Transformer sees the SAR image as a series of patches that don’t overlap. This helps it mimic long-range spatial interdependence. This is not the same as regular convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which use localised receptive fields. This is especially helpful for researching wildfires because the margins of the flames often have patterns that are uneven and spread out.

This process, visually represented in Fig. 6, begins by dividing the input image into patches:

where \(P\times P\) is the size of the patch and \(N=\frac{H}{P}\times \frac{W}{P}\) is the number of patches. Then, each patch is linearly projected into an embedding space:

where \(W_e \in \mathbb {R}^{d\times P^2}\) is a learnable projection matrix, \(b_e\) is a bias term, and d is the dimension of the embedding. The model then uses shifting window self-attention methods to effectively capture both local textures and global spatial dependencies:

where (Q, K, V) are projected feature representations. This hierarchical method makes the model better at telling the difference between areas that have been impacted by fire and complex SAR backscatter patterns, all while keeping the calculations quick.

Multi-scale feature enhancement

To improve feature learning from the Swin Transformer backbone, we incorporate a Feature Pyramid Attention (FPA) module, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The FPA module improves multi-scale representation by adding parallel self-attention pathways. This lets the model effectively capture both small-scale fire ignitions and huge wildfire spreads. Each pathway works on its own scale:

These multi-scale features are then aggregated:

To further preserve contextual coherence across resolutions, a Global Attention (GA) mechanism extracts a global context vector, which helps mitigate SAR-specific noise while retaining essential structural details for segmentation.

where \(\textrm{GAP}(\cdot )\) is Global Average Pooling. The final FPA-enhanced feature map is produced by fusing these components:

Decoder and high-resolution mask generation

The final stage of FPANet involves a hierarchical decoder that translates the enhanced features into a precise segmentation mask. This process begins with a Global Attention Upsample (GAU) module, which addresses the common challenge of boundary blurring during upsampling. GAU uses adaptive cross-attention to selectively merge high-level semantic information with low-level spatial features, ensuring sharp fire boundary delineation. The various steps involved in this process are depicted through Figs. 8, 9, 10.

where \(F_H\) and \(F_L\) are high-level and low-level features, respectively. This selective modulation accurately delineates fire boundaries, reducing misclassification in areas with varying SAR backscatter.

The central component of the decoder is the Pyramid Attention Network (PAN), which enhances features across various resolution scales through the integration of sequential GAU blocks and transformer layers. The complete hierarchical pipeline for processing these features is depicted in Fig. 11

Finally, the features are passed into a specialized Mask Classifier that uses a transformer architecture, specifically decoder to produce the final high-resolution fire mask needed.

where \(Q_m\) represents the mask queries that can be learnt. This classifier strikes a balance between semantic abstraction and spatial accuracy, making sure that the final output mask retains structural coherence. The final segmentation mask is determined by applying the equation below:

We use \(W_o\) to represent a projection matrix. Transformer-driven feature extraction and enhanced upsampling improve spatial coherence and identify fire from background areas in the FPANet architecture. CNN-based classifiers struggle with noisy SAR imagery, but this method works.

Component 2: UAV-based RGB-thermal fusion using DualSegFormer

Architectural overview

The Improved DualSegFormer acts as the second component of the proposed system. This segmentation model effectively analyzes RGB and thermal images captured from UAVs. This design facilitates the real-time observation of regions affected by fire, delivering high-resolution data. This addresses previous challenges associated with UAV-based sensing, including changes in lighting conditions, occlusions from smoke, and differences in spectral signatures. This approach employs dual-stream processing along with adaptive fusion techniques, enabling our SAR-based system to effectively monitor extensive regions. This provides the precise information required to extinguish the fire effectively.The full architecture for this dual-stream model is presented in Fig. 12.

Dual-Stream Encoder

The DualSegFormer architecture initiates with a dual-stream encoder, as detailed in Fig. 13. Two distinct encoders operate concurrently to process the RGB and thermal streams, after which their complementary features are integrated. This division is crucial for obtaining information relevant to each modality, free from interference.

-

The RGB encoder pathway collects detailed information regarding texture and colour, essential for distinguishing active fire areas from adjacent smoke and unburned vegetation under clear conditions.

-

The thermal encoder pathway analyses infrared signals to precisely identify heat signatures, enabling effective fire detection even in conditions of reduced visibility due to smoke or darkness.

The output of each encoder is a distinct feature representation for its respective modality:

In this context, \(E_{\text {RGB}}\) and \(E_{\text {Thermal}}\) represent the functions of the encoder. Both encoders employ optimised feature extraction blocks to maintain computational efficiency while safeguarding essential spatial and spectral information.

Adaptive feature fusion

Specialised fusion blocks are employed to adaptively integrate RGB and thermal features, efficiently combining information from both modalities. The blocks utilise a dynamic weighting mechanism that assesses the contribution of each modality based on the environmental context. The fused feature map is computed as a weighted sum.

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are dynamically learned weights determined by trainable parameters \(w_{\text {RGB}}\) and \(w_{\text {Thermal}}\):

This adaptive method ensures effective feature selection, prioritizing thermal features in low-visibility scenarios and RGB features in clear conditions, improving the model’s robustness.

Hierarchical decoding for precise segmentation

After fusion, the architecture uses a hierarchical decoder to systematically enhance the fused feature representations, which makes the segmentation boundaries very accurate. Each phase of the decoder, whose structure is shown in Figure 14, uses skip connections to combine upsampled data with information from the encoder level that is useful. This helps retain the right spatial details and the right meaning.

where \(F_{\text {dec}}^i\) represents feature maps at different hierarchical levels. This multi-scale approach ensures consistency between global fire patterns and local boundary characteristics.

The final segmentation mask is generated through a refined prediction pathway:

The model employs a composite loss function with intermediary supervision at various decoder levels to facilitate robust learning. This keeps the precision of segmentation across environments that change, which is very important for operational monitoring. The loss function is as follows:

where the Feature Similarity Loss (\(\mathscr {L}_{\textrm{Fso}}\)) specifically enforces effective RGB-Thermal fusion:

This integrated method, which combines high-resolution UAV data with broad-scale SAR monitoring, lays the groundwork for reliable fire detection and improves emergency response plans.

Modality-specific architectural design

The framework’s high performance is rooted in its modality-specific architectural design, which employs two specialized deep learning models: FPANet for SAR data and the Improved DualSegFormer for UAV imagery. This design is critical because SAR and UAV-based optical/thermal data represent fundamentally different sensing domains. A single, generalized architecture would be forced to make significant compromises between learning features for these disparate modalities, leading to suboptimal performance for both tasks.

-

SAR Data Characteristics: SAR is an active microwave sensing system that measures the backscatter of surfaces, capturing information about texture, roughness, shape, and dielectric properties. SAR images are characterized by speckle noise, geometric distortions, and information encoded in signal phase and amplitude, which is entirely different from optical data. FPANet is specifically designed with a Swin Transformer backbone and attention mechanisms tailored to handle these unique spatial patterns and mitigate noise, allowing it to learn meaningful representations from complex backscatter signals.

-

UAV Data Characteristics: UAVs provide passive optical (RGB) and thermal infrared data. RGB imagery is rich in color and texture, while thermal imagery captures emitted heat. The primary challenge here is the effective fusion of these two complementary data streams, especially when one (RGB) may be degraded by smoke. The Improved DualSegFormer is explicitly designed for this task, with its dual-stream encoders and adaptive fusion module that can dynamically prioritize the more reliable data source (e.g., thermal data when smoke is present).

Ultimately, this modality-specific approach avoids the performance trade-offs inherent in a generalized, one-size-fits-all model. FPANet is thus able to master the complexities of SAR backscatter, while DualSegFormer excels at robustly fusing multi-spectral UAV data. This specialization ensures that each component operates at peak performance, resulting in a detection and monitoring system with significantly greater accuracy, robustness, and operational reliability.

Stage 3: Semantic interpretation and reporting

Architecture for Prompt-Based Wildfire Analysis: UAV-derived temporal and static features, along with processed SAR data, are fed into a prompt generation engine. The generated prompt is then interpreted by an LLM (Large Language Model) to produce a synthesized textual analysis of wildfire behavior.

Architectural overview

The final stage of the proposed framework bridges the gap between raw pixel-level segmentation and actionable, human-readable intelligence. After the FPANet and DualSegFormer models generate spatial fire masks, the system transitions from detection to semantic interpretation. This is accomplished using a novel component powered by a Vision-Language Model (VLM) that contextualizes and communicates the wildfire’s evolving status. Unlike typical scene captioning systems, this VLM module is specifically designed to interpret multi-source, temporally dynamic fire data to generate mission-critical insights for decision-makers. The process involves three core steps: multi-source feature integration, dynamic prompt generation, and LLM-powered narrative synthesis.

Multi-source feature integration and prompt generation

This step synthesizes insights from both the broad-area SAR surveillance and the targeted UAV analysis into a unified, structured format. It is crucial to note that this is an information fusion process, where high-level derived metrics from both data sources are combined, rather than a direct pixel-level or feature-level fusion of the raw sensor data. The architecture for this prompt-based analysis pipeline is shown in Fig. 15.

At each observation timestep t, a composite feature vector \(F_{\textrm{composite},t}\) is constructed. This vector integrates:

-

UAV-derived static features from the high-resolution DualSegFormer mask (\(M_t\)):

-

Fire coverage ratio: \(C(t) = \frac{\sum M_t}{H \times W}\)

-

Region counts: \(N_{\textrm{regions}}(t)\)

-

Spatial pattern descriptors: \(\textrm{Pattern}(t)\)

-

Orientation: \(\textrm{Orient}(t)\) using image moments

-

Intensity proxy: \(\textrm{Intensity}(t)\)

-

-

Temporal dynamics extracted by comparing current and previous fire masks (\(M_t, M_{t-1}\)):

-

Newly ignited area: \(A_{\textrm{new}}(t)\)

-

Extinguished area: \(A_{\textrm{ext}}(t)\)

-

Net fire area change: \(\Delta C(t)\)

-

Growth direction: \(\textrm{GrowthDir}(t)\) via centroid displacement analysis

-

-

SAR-derived insights from the wide-area FPANet analysis (\(F_{\textrm{SAR},t}\)):

-

Canopy-penetrating fire signatures

-

Smoke-obscured burn evidence

-

Large-scale activity patterns and fire line detections

-

These extracted features are then programmatically structured into a semantically rich prompt, \(\mathscr {P}_t\), which is dynamically generated at each timestep to reflect the most current fire conditions. An example output might look like:

Findings: UAV analysis shows the fire covers \(C(t)\%\) of the area, forming a \(\textrm{Pattern}(t)\) pattern with \(N_{\textrm{regions}}(t)\) distinct clusters. SAR data confirms intense activity near the northern boundary. Over the last interval, the fire has grown with a \(\Delta C(t)\%\) net increase, particularly expanding towards the \(\textrm{GrowthDir}(t)\). Estimated fire intensity is \(\textrm{Intensity}(t)\).

LLM-powered narrative generation

The dynamically generated prompt \(\mathscr {P}_t\) is then passed to a fine-tuned, instruction-following Large Language Model (LLM). The prompt concludes with a direct instruction, such as: “Synthesize the above into a concise report summarizing the fire’s status and potential risks.”

The LLM processes this input and generates a paragraph-length analysis, \(T_t\), that captures the wildfire’s spatial behaviour, temporal evolution, and current threat level in natural language. This output serves as the final, high-level layer of the pipeline, offering interpretable, data-driven situational awareness for emergency responders.

It is important to note that the VLM is not trained in the traditional sense of fine-tuning its weights. Instead, the training paradigm focuses on refining the prompt engineering framework and the fidelity of the feature extraction algorithms. Thresholds for intensity, region aggregation, and temporal deltas are iteratively calibrated against a curated validation set to optimize the quality and accuracy of the generated narratives. This creates an end-to-end chain, from sensor-driven segmentation to dynamic, LLM-assisted linguistic abstraction. By embedding this interpretive layer, the system transcends pixel-level understanding and becomes a comprehensive cognitive tool for modern wildfire management.

Results

Evaluation metrics

Custom Loss, F1-score, Intersection over Union (IoU), and Pixel Accuracy are the four most important measures that we used to judge how well wildfire detection programs work. These metrics give a whole picture of how well detection and segmentation are working by looking at accuracy, recall, and total pixel-level correctness.

Custom loss function

The proprietary loss function is made to balance pixel-wise precision, form consistency, and feature-level similarity such that the model learns useful segmentations. It has Dice Loss, Cross-Entropy Loss, and an optional Feature Similarity Loss for models that use multimodal fusion (such RGB + Thermal). The overall loss is calculated as:

where: \(\mathscr {L}_{\textrm{Dc}}\) ensures segmentation masks closely match ground truth by maximizing the overlap:

\(\mathscr {L}_\textrm{C}\) (Cross-Entropy Loss) penalizes incorrect classifications at the pixel level:

\(\mathscr {L}_{\textrm{Fso}}\) (Feature Similarity Loss) ensures that multimodal feature maps remain structurally aligned:

The hyperparameters \(\lambda _1, \lambda _2\) and \(\lambda _3\) control the weight of each loss term, allowing for tuning based on dataset characteristics. By combining these losses, the model achieves better segmentation accuracy, smoother mask boundaries, and improved feature consistency.

F1-score

The F1-score provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall, ensuring a balanced evaluation of false positives and false negatives. It is given by:

High F1-scores suggest that models of wildfire detection find fire pixels minimising false alarms and missing detections. This statistic is important for model dependability evaluation since over-detection (false positives) and under-detection (false negatives) can have major consequences in real-time applications.

Intersection over Union (IoU)

IoU, also known as the Jaccard Index, measures the overlap between predicted and ground truth fire regions. It is calculated as:

Where \(y_{\textrm{true},i}\) is the ground truth binary mask, \(y_{\textrm{pred},i}\) is the predicted binary mask, \(N\) is the total number of pixels. IoU is a stricter metric than F1-score because it penalizes both false positives and false negatives more heavily. Higher IoU values indicate better segmentation accuracy, particularly for models that need to provide precise fire region delineation.

Pixel accuracy

Pixel accuracy is the simplest metric, measuring the proportion of correctly classified pixels over the entire image:

While high pixel accuracy may suggest good performance, it can be misleading in scenarios with class imbalance. In wildfire detection, where fire pixels are sparse compared to background pixels, a model could achieve high pixel accuracy simply by predicting most pixels as background. Therefore, pixel accuracy should always be interpreted alongside other metrics like Dice Loss and IoU.

Semantic similarity

Semantic similarity measures the degree of alignment in meaning between the model’s generated output and a reference response. It is commonly computed using cosine similarity between sentence embeddings derived from transformer-based models. Given two embedding vectors \(\vec {u}\) and \(\vec {v}\), the similarity is defined as:

This metric captures contextual alignment even when there is low lexical overlap, making it suitable for evaluating paraphrased or restructured responses.

Instruction following score

The instruction following score assesses how accurately a model adheres to multi-step commands or structured tasks. This is particularly important for evaluating compliance in task-oriented scenarios. The score can be approximated as a weighted sum of BLEU score and exact match:

here \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are tunable weights summing to 1. Higher scores indicate the model’s ability to correctly interpret and act on specified prompts.

Context retention score

Particularly in long or multi-turn interactions, this statistic measures a model’s capacity to retain and make use of earlier parts of a prompt. One can get an estimate by comparing the final output with the overlap or alignment of the referenced earlier material. Earlier input segments and the produced output embeddings are subjected to a cosine similarity formulation:

This is particularly critical for applications requiring sustained memory and logical consistency over extended interactions.

Reasoning ability score

The reasoning score checks how well the model can make logical deductions, understand cause and effect, and think through multiple steps. Usually, assessment is done by comparing chains of thought or incremental logical validation. An overall estimation uses the average similarity between the different steps of reasoning:

Here, \(r_i\) and \(g_i\) represent individual steps in the reference and generated reasoning chains, respectively. Higher values indicate better logical flow and justification.

Modality adaptability score

Modality adaptability illustrates how well the model can combine and use data from different types of inputs, such as text, photos, and sensor data. It is especially important for vision-language models and multi-modal decision systems. The score represents the average performance of the modalities:

where \(m_i\) denotes a specific modality and \(\textrm{Performance}(m_i)\) can refer to any task-relevant metric such as accuracy or similarity. This measure captures the model’s flexibility and generalization across diverse data types.

ROUGE-L score

Automatically generated text summaries are evaluated using the Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation - Longest Common Subsequence (ROUGE-L) score. ROUGE-L measures the longest co-occurring in-sequence word subsequence between a candidate summary and a reference summary, unlike n-gram overlap metrics. This technique captures sentence-level structural similarity without contiguous matches, improving content overlap evaluation.

where \(R_{\textrm{lcs}} = \frac{\textrm{LCS}(C, R)}{|R|}\) and \(P_{\textrm{lcs}} = \frac{\textrm{LCS}(C, R)}{|C|}\). Here, \(C\) is the candidate text, \(R\) is the reference text, \(\textrm{LCS}(C, R)\) is the length of their longest common subsequence, and \(|C|\) and \(|R|\) are their respective lengths. A higher ROUGE-L score indicates a greater degree of content and structural alignment.

BERTScore

BERTScore uses semantic analysis to fix the problems with lexical overlap assessments. Instead of aligning words exactly, contextual embeddings from a pre-trained language model like BERT are utilised to compare tokens in candidate and reference texts. This helps keep the meaning the same even when the words are different (“fire spread” vs. “flame propagation”). We quantify precision, recall, and an F1-score based on the best alignment of token embeddings.

where \(R_{\textrm{BERT}} = \frac{1}{|R|} \sum _{r_i \in R} \max _{c_j \in C} \textbf{r}_i^T \textbf{c}_j\) and \(P_{\textrm{BERT}} = \frac{1}{|C|} \sum _{c_j \in C} \max _{r_i \in R} \textbf{r}_i^T \textbf{c}_j\). Here, \(\textbf{r}_i\) and \(\textbf{c}_j\) are the contextual vector embeddings for tokens in the reference \(R\) and candidate \(C\), respectively. BERTScore provides a nuanced measure of textual quality by prioritizing semantic meaning, making it highly suitable for evaluating the interpretability of generated analyses.

FPANet results

Experimental setup

The model was trained for 50 epochs using the AdamW optimiser. This optimiser is noted for being good in training architectures that are built on transformers. To stop overfitting, we set the initial learning rate to 1e-4 and the weight decay to 0.01. A cosine annealing learning rate scheduler was utilised to steadily lower the learning rate during the training session. This helped the model find a more stable minimum. The test was run using the PyTorch deep learning framework on one NVIDIA Tesla V100 with a batch size of 8. To establish a fair balance between overlap and classification accuracy, the weights for the custom loss function were set to \(\lambda _1=0.6\) and \(\lambda _2=0.4\) based on real-world data.

Performance analysis

The findings show that the suggested FPANet architecture performs better than conventional models in wildfire segmentation using SAR images. FPANet shows improved fire-affected area delineation with lower Dice Loss and higher F1-score and IoU. Two challenges in SAR imaging - speckle noise and complex backscatter effects - are alleviated through using Feature Pyramid Attention (FPA) and Global Attention Upsample (GAU), improving feature extraction and multi-scale learning.The training and validation loss curves, depicted in Fig. 16, show stable convergence over 50 epochs.

FPANet shows better overlap between predicted and real fire areas, along with greater segmentation accuracy than U-Net and Attention-U-Net. Although FPANet produces better overall segmentation accuracy, transformer models like UNETR-2D and SwinUNETR-2D enjoy the advantage of self-attention mechanisms allowing enhanced feature representation.A comparison of loss progression in Fig. 17 confirms FPANet’s efficient learning, while the qualitative results in Fig. 18 demonstrate its accurate segmentation of fire regions. This shows that FPANet is more robust for SAR-based fire detection by efficiently capturing both local and global context information by combining convolutional and attention-based methods. Table 3 presents a detailed quantitative comparison of these models.

FPANet’s High Pixel Accuracy further demonstrates its competency in classifying between background and fire areas. Because SAR data class imbalances are a probability, pixel accuracy as a standalone measure is not reliable; however, its correlation with high IoU and F1-score values demonstrates the general improvement in segmentation performance. The results demonstrate that FPANet offers a stronger segmentation paradigm, overcoming critical drawbacks of prior work and enhancing the consistency of fire detection in SAR-based wildfire surveillance.

DualSegFormer results

Experimental setup

The DualSegFormer model was trained under a similar configuration for 50 epochs. We again utilized the AdamW optimizer but with a slightly lower initial learning rate of 6e-5 to accommodate the dual-stream architecture and encourage finer-grained feature learning. The training was conducted with a batch size of 4, a setting chosen to manage the increased memory requirements of processing paired RGB and thermal images simultaneously. For the composite loss function, the weights were set to \(\lambda _1=0.5\), \(\lambda _2=0.3\), and \(\lambda _3=0.2\) to effectively balance the contributions from Dice Loss, Cross-Entropy Loss, and the Feature Similarity Loss term.The model’s training progression, shown in Figure 19, indicates well-converged training with minimal overfitting.

Performance analysis

The findings indicate that DualSegFormer outperforms traditional techniques in segmenting wildfires utilising UAV imagery. The reduced Dice Loss, alongside the elevated F1-score and IoU, indicates that DualSegFormer more effectively delineates boundaries through dual-stream processing and adaptive feature fusion. The integration of RGB and thermal data enhances the model’s ability to address challenges such as smoke obstruction and varying light conditions. This enhances the accuracy of segmentation in practical applications.

This plot compares the dynamics of training loss of various UAV-based wildfire detection models. The DualSegFormer (UAV) model presents the steadiest and fastest fall in both Dice Loss and Custom Loss, implying better segmentation quality and quicker convergence. Models such as YOLOv10 and YOLOv9 present slower advancement and greater terminal loss values, implying relatively constrained segmentation accuracy in wildfire environments.

DualSegFormer demonstrates a significant enhancement in segmentation performance when compared to U-Net-based models. U-Net models, specifically those utilizing the FLAME and Private datasets, demonstrate effective performance; however, they are limited by their exclusive reliance on encoder-decoder architectures, which may encounter difficulties in extracting multi-modal features. The hierarchical attention mechanisms and deep supervision of DualSegFormer enhance spatial representation, resulting in improved IoU and F1-score metrics.

Methods based on object detection, including YOLO and Faster R-CNN, demonstrate competitive performance, especially in fire localization tasks. Nonetheless, their segmentation performance typically falls short compared to DualSegFormer and U-Net-based models, as indicated by elevated Dice Loss and diminished IoU scores. Faster R-CNN demonstrates high Pixel Accuracy; however, it does not directly rival segmentation models regarding the precise extraction of fire regions. SSD and YOLO variants exhibit satisfactory performance; however, they do not achieve the fine-grained segmentation capabilities found in specialized segmentation models.The superior convergence of DualSegFormer is highlighted in Fig. 20, and its qualitative accuracy is demonstrated by the segmentation masks in Fig. 21 and the false positive analysis in Fig. 22.

Comparison of ground truth and predicted masks in wildfire segmentation results. Each row displays a distinct sample, including the input image, ground truth mask, predicted mask, and areas of false positives, marked in red. The IoU score quantifies the overlap between predicted and actual fire regions, highlighting the distinctions in false positive and false negative areas.

The enhancements demonstrated by DualSegFormer confirm its efficacy in UAV-based wildfire monitoring. The model attains improved segmentation accuracy through the utilization of attention-based fusion and deep feature extraction, thereby enhancing fire boundary detection and facilitating real-time situational awareness. The findings underscore the importance of multi-modal fusion architectures in enhancing wildfire detection and response strategies. The full quantitative results are summarized in Table 4.

VLM results

The assessed various Visual-Language Models (VLMs) is integrated into the post-prediction interpretation framework. The assessment of these models included several criteria: semantic similarity, compliance with instructions, context retention, reasoning ability, and adaptability to visual modalities. LLaMA3-8B consistently outperformed other models in maintaining context consistency and providing clear, threat-aware assessments of wildfires. This method enhances real-time catastrophe assessment systems by accurately interpreting segmented fire masks and demonstrates the evolution of growth patterns over time. Mistral, being somewhat lighter, performed effectively in competitions due to its robust reasoning capabilities and adherence to instructions (Table 5). This rendered it appropriate for situations where time is of the essence. Models such as Phi3 and Gemma demonstrate high efficiency; however, this efficiency is accompanied by a reduction in semantic accuracy and contextual richness. This may diminish their utility in reporting on intricate wildfire events. Qwen exhibited difficulties in multi-modal interpretation and domain-specific inference; however, it performed effectively in generating broad summaries. A qualitative summary of these capabilities across different models is provided in Table 6.

To quantitatively evaluate the semantic consistency of the generated outputs, we benchmarked the models against a high-quality reference. To establish this “gold-standard” summary, we utilized Google’s state-of-the-art Gemini 2.5 Pro model, providing it with the same structured prompt and visual data. Its generated text served as an objective reference against which we evaluated our more deployable models. We employed two key metrics for this comparison: ROUGE-L, to measure lexical overlap, and BERTScore, for a deeper assessment of semantic similarity using contextual embeddings.

The results, presented in Table 5, provide quantitative validation of our qualitative findings. LLaMA3-8B demonstrates the highest semantic alignment with the Gemini 2.5 Pro reference, confirming its status as the top performer among the tested models. Mistral also achieves a strong score, positioning it as a highly viable alternative. As expected, the smaller models show a greater semantic distance from the reference, underscoring the trade-off between deployment efficiency and descriptive richness.

Moreover, the ability of our system to process temporally changing fire masks across several frames helps VLMs to deduce wildfire trajectory, intensity changes, and possible spread direction–insights vital to predictive modeling and early warning systems. Models such as LLaMA3 and Mistral illustrate the temporal evolution of fire incidents by capturing dynamic patterns. This provides respondents with a superior comprehension of the situation compared to single static frame analysis. Examples of this spatiotemporal analysis, comparing model outputs and tracking dynamic changes over time, are shown in Figs. 23 and 24. The results demonstrate that the incorporation of sophisticated segmentation frameworks, such DualSegFormer and FPANet, alongside high-performance VLMs, markedly improves spatial and temporal interpretability in wildfire monitoring. Integrating pixel-wise forecasts with temporal natural language explanations provides essential insights for making informed, real-time decisions during rapidly evolving fire scenarios.

The visualisations depict the ground truth fire mask, the prior prediction, and the current prediction for a wildfire scenario, accompanied by the relevant generated textual analysis. Both models comprehend the spatiotemporal dynamics of the fire; LLaMA3-8B demonstrates superior semantic accuracy and contextual depth in delineating the spread pattern, intensity, and directional progression. Mistral provides a clear overview that includes significant statistics such as spatial fragmentation and percentage change.

The picture shows how wildfire predictions have changed over time by using historical and present fire mask outputs combined with the ground truth data that goes with them. Visual-Language Models (VLMs) look at time sequences to create rich, context-aware summaries that show how the fire grew, where it went, and how its intensity changed. Both outputs show how small net changes, like +5.8% or +1.7%, and declines effect threat appraisal. This gives us an idea of how the fire’s dynamic features alter from frame to frame.

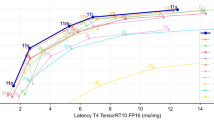

Robustness and efficiency analysis

While the primary focus of this work was on segmentation accuracy, understanding the computational performance and generalization capability of our models is crucial for assessing their potential for operational deployment. To this end, we quantified both the inference latency and the cross-regional robustness of our architectures.

The initial latency evaluation was performed on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, measuring the average time required to process a single image over 100 runs. As shown in Tables 7 and ‘ 8, the original FPANet and DualSegFormer models achieved speeds of 11.8 FPS and 8.3 FPS, respectively. While effective, these speeds are insufficient for real-time applications. To address these latency bottlenecks, structured model pruning is applied to reduce computational complexity while minimizing degradation in accuracy. The results of this optimization are highly encouraging: the pruned FPANet achieved a real-time capable speed of 24.4 FPS, while the pruned DualSegFormer’s speed increased to 17.5 FPS, both with only a marginal drop in F1-score. This demonstrates a viable path toward efficient deployment.

Beyond computational efficiency, we also investigated the models’ generalization capabilities by evaluating their performance on held-out wildfire datasets from two distinct international regions: the boreal forests of Canada and the eucalyptus woodlands of Australia. Both models demonstrated strong transferability, maintaining high segmentation performance despite significant variations in vegetation, terrain, and fire dynamics. For instance, FPANet maintained an F1-score above 0.80 on the Canadian dataset, and DualSegFormer achieved an F1-score of approximately 0.92 on Australian bushfire imagery. However, this cross-regional validation also highlights a broader challenge: the limited availability of publicly accessible, curated, multi-modal wildfire datasets from diverse global biomes. While our tests on Canadian and Australian data build confidence in the models’ robustness, the lack of standardized benchmark datasets from other fire-prone regions like the Mediterranean or South America remains a limiting factor for truly comprehensive global validation.

Ablation study: FPANet with and without pyramid attention network

Pyramid Attention Network (PAN) is the backbone of FPANet since it adds multi-scale spatial attention to sensitive feature representation before being processed in the Global Attention Upsample (GAU) module. PAN achieves this through modeling of global contextual relationships and subtle patterns in local areas, crucial for outlining complex wildfire regions in SAR and UAV-based thermal imagery. Our ablation study estimates its impact by comparing model performance with and without PAN. With PAN, the model has stable learning and good generalization, successfully encoding both global and local contextual cues for wildfire segmentation. Multi-scale spatial attention further improves feature refinement, resulting in accurate segmentation edges and better overall accuracy. The ordered processing supplied by PAN makes sure the network can tell fire areas from the background even in tough cases with occlusions, low contrast, or different thermal intensities.

In contrast, without PAN, the model experiences a noticeable decline in performance due to the direct connection between encoder features and GAU. Without the structured refinement of PAN, the upsampling process lacks the necessary multi-scale feature aggregation, leading to weaker spatial awareness and less discriminative segmentation maps.The impact on custom and training loss is quantified in Table 9.

In the absence of PAN, encoder feature maps are transmitted directly to GAU via standard skip connections, effectively bypassing the structural refinement offered by PAN. GAU, while beneficial for the progressive recovery of resolution, lacks the ability to integrate cross-scale feature dependencies as PAN does. This causes a decrease in the quality of segmentation because GAU has fewer informative and spatially coarse features, thus complicating the separation of fire and non-fire areas. In the absence of PAN, the network is unable to effectively learn robust representations of fire edges, especially in conditions characterised by low contrast, occlusions, or variations in thermal intensity. The feature maps lack sufficient resolution to accommodate these changes, leading to diminished IoU and Dice Score, thereby impacting the reliability of wildfire detection.

The incorporation of PAN is crucial in high-variance and complex environments such as wildfire segmentation, where both fine textures and overall spatial context are essential for accurate prediction. PAN enhances feature maps before upsampling, enabling GAU to obtain dense, multi-scale context essential for effective reconstruction. Excluding PAN decreases computational overhead, albeit at the expense of accuracy; however, the trade-off in segment accuracy is significant. Fire regions display diverse spatial scales, and the unstructured network of PAN fails to effectively integrate fine-grained and coarse-grained features, leading to imprecise segmentations and an increased occurrence of false positives and negatives. The ablation experiment confirms that PAN is a crucial component of FPANet, enhancing both accuracy and stability in wildfire detection tasks.

Ablation study: DualSegFormer with and without hierarchical decoding

An ablation study was performed on the DualSegFormer model to evaluate the effect of hierarchical decoding on its performance. Hierarchical decoding consistently improves feature representation across various scales. This facilitates the monitoring of spatial details and enhances the precision of segmentation. The incorporation of hierarchical decoding into the model facilitates the integration of features across varying scales, thereby enhancing border delineation and generalisation. The model directly upsamples high-level decoded features to produce the final segmentation map without undergoing progressive refinement. This occurs due to the absence of hierarchical decoding. The model fails to accurately represent smaller fire zones due to the loss of fine-grained spatial characteristics. Segmentation masks exhibit reduced precision and increased inaccuracies in object identification in the absence of progressive decoding. This is particularly applicable in complex and dynamic wildfire environments characterised by diverse dimensions and intensities.The performance comparison, highlighting the impact on training stability, is shown in Table 10.

Empirically, the experiment demonstrates that DualSegFormer with hierarchical decoding performs considerably better in training and validation processes with lower loss values and more stable convergence. Without hierarchical decoding, the model cannot preserve fine details and has higher loss values, reflecting worse feature reconstruction. This indicates the significance of hierarchical decoding in enhancing wildfire segmentation by facilitating better multi-scale feature fusion and refinement.

Discussions

The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of our modality-specific, multi-scale framework for wildfire monitoring. By leveraging SAR for broad-area, all-weather cueing and UAVs for high-fidelity local analysis, our approach presents a more robust and operationally viable system than single-modality methods. The strong performance of FPANet on noisy SAR data and DualSegFormer on multi-modal UAV imagery underscores the importance of tailoring architectures to the unique characteristics of the sensor data.

Despite the strengths of our fusion strategy, we acknowledge a key operational limitation related to the temporal latency between the different sensing modalities. Our framework relies on SAR for initial, wide-area detection to cue UAV deployment. However, the Sentinel-1 satellite has a revisit cycle of 6–12 days. In the case of rapidly developing wildfires, a fire could ignite and spread significantly within this temporal gap, potentially delaying the initial satellite-based detection. Furthermore, even with near-real-time SAR data processing, the logistical delay in dispatching a UAV to a remote location presents a practical challenge. This inherent latency means our system is better suited for monitoring large, established fires or for post-fire burn scar assessment rather than capturing the moment of ignition for every new event.

Future work

A key avenue for future research is addressing the challenge of real-time deployment. As the analysis of inference latency of the research findings indicates, the current architectures are not yet optimized for on-the-fly processing on resource-constrained platforms. To bridge this gap, future work will focus on creating lightweight learning models and to explore a range of state-of-the-art optimization techniques, including:

Quantization: To convert model weights from 32-bit floating-point to 8-bit integers, significantly accelerating computation on compatible hardware.

Knowledge Distillation: To train smaller, faster “student” models that mimic the performance of our larger, more accurate “teacher” models.

Beyond model optimization, this research intends to investigate decentralized frameworks, such as federated learning across UAV swarms, to enable scalable and adaptive monitoring systems while preserving data privacy.

Conclusion

This research paper introduces a novel hybrid framework for wildfire detection that synergistically integrates wide-area SAR surveillance with high-resolution UAV-based thermal and RGB imagery. We presented two specialized deep learning architectures tailored to the unique challenges of each data modality. The two specialized deep learning architectures tailored to the unique challenges of each data modality was presented in this research. The core findings demonstrate the efficacy of this approach. First, the proposed FPANet successfully segments burn scars from noisy SAR imagery, achieving a robust F1-score of 0.830. Second, the Improved DualSegFormer effectively fuses multi-modal UAV data to achieve precise fire front delineation, attaining a superior F1-score of 0.946. Collectively, the main contribution of this work is the validation of a multi-scale, modality-specific strategy that leverages the strengths of different remote sensing platforms for more comprehensive and reliable wildfire monitoring. By advancing the capabilities of AI-powered detection, this research offers a meaningful step toward more resilient ecosystem management and effective disaster response, in alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 15.

Data availibility

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shaik, R. U. et al. Fuelvision: A multimodal data fusion and multimodel ensemble algorithm for wildfire fuels mapping. arxiv:2403.15462 (2024). Accessed 19 Mar. (2025).

Barco, L., Urbanelli, A. & Rossi, C. Rapid wildfire hotspot detection using self-supervised learning on temporal remote sensing data. In IGARSS 2024, 2061–2065 https://doi.org/10.1109/igarss53475.2024.10641631(2024).

Ghali, R., Akhloufi, M. A. & Mseddi, W. S. Deep learning and transformer approaches for uav-based wildfire detection and segmentation. Sensors 22, 1977. https://doi.org/10.3390/S22051977 (2022).

Jonnalagadda, A. V., Hashim, H. A. & Harris, A. Comprehensive and comparative analysis between transfer learning and custom built vgg and cnn-svm models for wildfire detection https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDS62089.2024.10756303 (2024).

Zhao, N. et al. An efficient wildfire detection system for ai-embedded applications using satellite imagery. Fire https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6040169 (2023).

Ustek, I., Arana-Catania, M., Farr, A. & Petrunin, I. Deep autoencoders for unsupervised anomaly detection in wildfire prediction. arxiv:2411.09844 (2024). Accessed 19 Mar. (2025).