Abstract

In order to study the distribution of strain in concrete at different times and positions under internal expansion pressure, experiments with a soundless chemical demolition agent (SCDA) were conducted on cubic concrete with one hole, and Distributed Optic Fiber Sensing (DOFS) technology, in comparison to a static strain tester, was used to measure the expansion strain of concrete, evaluate its cracking time, and theoretically calculate the expansion tensile stress at the cracking time. The test results show that there was a linear correlation between strain with time but a negative correlation with distance from the hole. Additionally, the strain-position peak shapes at different times aligned with classical mechanics principles. Under pressure from SCDA in the central hole (40 mm in diameter), the cracking time of a 150-mm C40 cubic concrete was evaluated as 73.3 min. DOFS technology exhibits higher accuracy and sensitivity than the static strain tester in evaluating the strain and cracking time of concrete.It can also reflect the spatial distribution information of strain, which can be applied to research on various expansion materials and structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Soundless chemical demolition, also known as static blasting1, is a construction techonique that uses a soundless chemical demolition agent (SCDA) to apply expansion pressure to the interior of concrete or rock, gradually causing it to crack, with the aim of removing the concrete or rock. SCDA is a kind of powdery material primarily composed of calcium oxide (CaO), anhydrite (CaSO4), and some silicate solids. SCDA is mixed with water to form a slurry, then is placed into drilled holes. As SCDA hydrates, the slurry hardens, the temperature rises, and the volume expands. The maximum expansion stress of calcium oxide can reach 30 MPa to 80 MPa2. When the expansion force reaches a certain level, micro-cracks first appear at the stress concentration points inside the material. These micro-cracks typically occur in the weakest parts of the material or where defects are present. Once the crack is triggered, it begins to expand gradually under the continuous expansion force. The propagation direction of cracks is influenced by multiple factors, such as the mechanical properties of the material, the micro-pore structure, mineral heterogeneity, mass defects, etc3,4. As the cracks continue to expand, they eventually penetrate each other, forming a macroscopic fracture. Soundless chemical demolition technology has obvious technological advantages in fields such as flood prevention, earthquake disaster relief, and military engineering, as it avoids hazards such as vibration, noise, dust, air shock waves, and flying rocks5,6.

Zhang, H.7 defined the ratio of the concrete area within the circumcircle of the specimen to the area of the expansion agent as the constraint ratio and used it to represent the degree of constraint of concrete on the expansion agent. The constraint ratio is an indicator to measure the degree of constraint of concrete on the expansion agent. As the constraint ratio increases, the volume expansion rate of the expansion agent decreases, and the crushing effect weakens. When the constraint ratio is relatively large, the constraint ratio has a major influence on the cracking time. The larger the constraint ratio, the longer the cracking time. Li R.S.8 has found that the cracking time of concrete is shortened with increased internal expansion or decreased external constraint. The size of the pore diameter has a significant influence on the expansion rate and crushing effect of the expansion agent. As the hole diameter increases, the volume expansion rate of the expansion agent also increases, and the crushing impact becomes better9. Wang, L.10 found that the maximum expansion pressure approximately increases linearly with the increase of the inner diameter. Li R.S.11 has found that the expansive pressure increased with the increment of hole diameter and showed a linear relationship within 2 days. The development regularity of the expansive pressure is not linear with the constraint coefficient. After the cracks develop stably, their distribution patterns include three types: “Y” shape, “T” shape, and “X” shape12. Wang J.L.13 found that the crack first initiated at the top surface and then expanded to the depth of the boreholes with time. When the hole depth is less than 70% of the plate thickness, the cracks caused by the hardening and expansion of the expansion agent slurry can no longer extend downward to the bottom of the thick plate. When the hole depth increases from 70% of the plate thickness to 90%, the crushing effect gradually improves. When the hole depth is 80% of the plate thickness, the number of blocks formed after crushing is the largest14. Habib, K.M.15 has found that fracturing time decreases with increasing borehole size, and the uniaxial compression reaches 5 MPa as early as 7 hours when the borehole spacing to borehole diameter ratio of 12.8 to 14.6. Jiang Z.S.16 found that the increased hole diameter corresponded to advanced cracking and improved crushing effect, and the increased concrete strength and hole spacing corresponded to delayed cracking and weakened crushing effect. Cho, H.5 has estimated the minimum expansion pressure required to form cracks connecting. Zhang, W.17 found that when the lateral pressure is less than 10% uniaxial strength, the peak stress and elastic modulus increase with the increase of lateral pressure; but when the lateral pressure is larger than 10% uniaxial strength, the two parameters decrease slightly or remain steady. Kyeongjin Kim18 found that the minimum required pressure for forming cracks was considered either linearly or non-linearly proportional to the concrete strength.

Traditional methods for testing material expansion performance predominantly rely on resistive strain gauges15. However, strain gauges measure at a single point and can only reflect the strain conditions on one surface. Distributed optical fiber sensing (DOFS) technology is becoming increasingly mature. DOFS based on backward Rayleigh scattering have already shown the potential to replace traditional resistive strain gauges and fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors in many fields. DOFS feature extremely high measurement point density, controllable spacing, lightweight, corrosion resistance, electrical insulation, high precision, and good repeatability19. Additionally, due to their relatively soft and tough texture, DOFS exhibit good adaptability to the shape of structural surfaces. DOFS technology can accurately measure the strain distribution within a certain range. It not only realizes quantitative strain measurement but also reflects the spatial distribution information of strain, achieving the strain positioning function20,21. Applying this technology to measure the expansion performance during static blasting can accurately determine the stress-strain conditions at different positions and the changes of strain over time, providing precise theoretical guidance for the design of hole spacing, hole depth, and the amount of expansion agent used in static blasting technology.

The cracking of materials such as concrete under expansion pressure is not only the key mechanism of static blasting technology but also critical for assessing the safety of engineering structures affected by expansion cracks. In order to study the distribution of strain in concrete at different times and positions under internal expansion pressure, this paper designs an experiment on cubic concrete with a single hole, using DOFS technology to measure the expansion strain and evaluate the cracking time of the concrete under SCDA pressure, with comparisons to the results obtained by a static strain tester.

Experimental

Materials

HSCA-Ⅲ SCDA was produced by Shijiazhuang Functional Building Materials Co., Ltd, and the contents of CaO, SO3, Al2O3 and MgO are 51–53%, 25–28%, 8–10% and 2–4% respectively.

The size of the cubic concrete specimen is 150 × 150 × 150 mm; the depth of the reserved central hole exceeds 117 mm, and the hole diameter is 40 mm.

BMB120-80AA(11)-P300-D strain gauges produced by Chengdu Electric Sensing Technology Co., Ltd. were used. The strain gauge has a length of 90 mm and a gage factor of 2.11±%, which were attached to the center of the outer surface of the concrete blocks, parallel to the surface. DH3818Y static strain tester (24 channels) was used to measure the strain, with a strain range of ± 60,000µε and a static sampling rate of 5 Hz.

Preparation of test specimens

Two strain gauges were placed on each of the four sides of the concrete, with an average distance of 20 mm and 75 mm from the upper surface. To ensure the adhesive layer was free of air bubbles, wrinkles, or cracks, a thin layer of cyanoacrylate glue (≤ 0.1 mm thick) was applied to the base of the strain gauge and the surface to be measured. The strain gauge was then covered with a polytetrafluoroethylene film and pressed for 1–2 min. Subsequently, it was heated with a hot air gun at 60–80 °C for 3–5 min to accelerate the curing process. Finally, it was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature to prevent cracking of the adhesive layer. The upper and lower sets of four strain gauges were numbered sequentially as U1-U4 and D1-D4, respectively.

Optical fibers were arranged on the concrete surfaces as shown in Fig. 1, with 3 cm reserved at the tail and 10 cm at the head. To prevent the optical fibers from being damaged during the test, yellow sheaths were used to protect the exposed optical fibers. A high-shear-modulus epoxy adhesive was used to enhance strain transfer efficiency.

The grating area must be in full contact with the surface of the object to be measured to avoid strain transmission loss caused by the suspension or excessive adhesive layer (the adhesive layer thickness was less than 0.1 mm). A spectrometer was used to locate the wavelength reflection point at the center of the grating (in the 1550 nm band), and mark the grating area (5–20 mm in length). Although the adhesive’s shear strength and shear modulus decrease with increasing temperature, temperature compensation was not performed for the installed fiber optic sensors. This was because measurement time was only 2–3 h and the indoor environmental temperature showed minimal variation.

The surface temperature of SCDA was recorded using an infrared thermal imager (UNI-T UNi-32, 32 × 32 pixels, resolution of 0.1 °C, thermal sensitivity of 0.15 °C). The ambient room temperature was 14.5℃. The width and depth of surface cracks in concrete samples were tested using an HC-F900 concrete Crack Defect Comprehensive Tester. The depth measurement range was 5 mm to 500 mm, and the width measurement range was 0.01 mm to 10 mm. The optical distributed sensor interrogator DOFS system was produced by LUNA Company (Luna A50, USA).

Concrete is prepared using medium sand, 5–20 mm crushed stone, with a sand ratio of 0.31. The compressive strength of the concrete is 42 MPa, and the splitting tensile strength is 2.93 MPa. SCDA was mixed with water at a ratio of 1:2.9, then filled into the reserved holes. The micromorphology of SCDA slurry was investigated using a JSM-5900 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) at 15 kV (JEOL, Japan).

Results and discussion

Morphology and temperature change of slurry and concrete

The morphology changes of the SCDA slurry and concrete over time are shown in Fig. 2.

As observed in Fig. 2, the slurry surface declined slightly after approximately 30 min, then began to expand, forming bulges and a network of craze cracks after 60 min. Visible cracks on the concrete appeared first at 84 min, detectable with the naked eye. Because the reserved hole depth was less than the height of the concrete, cracking was initiated at the top, and gradually widened, finally propagated to the base of the concrete block.

The measured crack widths are presented in Fig. 3.

At 84 min, the crack width near the central hole was 0.22 mm, and the crack width far from the hole was 0.16 mm. It took approximately 10 min from the appearance of the crack to its penetration. Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology provides continuous, accurate, and full-field monitoring of surface strain and crack propagation under non-contact conditions. This technique can be used to obtain the full-field strain distribution and track the variation of the crack tip opening displacement22,23. To enable more accurate determination of crack performance, future work will combine DIC and DOFS technologies.

The temperature-time curve of the slurry is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4 shows that the temperature remains at 20℃ for the first 30 min, and then increases gradually to the first peak temperature of 43.7℃ at 78 min, and the second peak temperature of 82.3℃ at 88 min. When the concrete first exhibited visible cracking at 84 min, the SCDA slurry’s surface temperature was 43.5℃. At this stage, the temperature remained stable for a period of time, so the cracking time cannot be determined from thermal data alone. As the crack propagated, the hydration of the expansion agent accelerated, causing the temperature to rise rapidly and then gradually dropped.

Although a rise in temperature can lead to volumetric expansion, crack formation does not correlate with peak temperatures, which suggests that concrete cracking primarily results from internal crystallization-induced expansion within the slurry components, rather than thermal expansion alone.

Chemical mechanism of expansion

The SCDA contained a large amount of active CaO, Al2O3, and 25–28% SO3, while the SO3 content in ordinary cement is less than 3.5%. When encountering water, CaO particles immediately begin to hydrate to form Ca(OH)2 crystals, releasing a lot of heat. When most of the calcium oxide has completely hydrated, the slurry temperature gradually drops to room temperature. CaO hydration requires a large amount of water, resulting in the initial slurry surface decline. The hexagonal sheets of Ca(OH)2 crystals fill the pore space as the solid volume increases by approximately 97%, leading to gradual volume expansion.

In the presence of sufficient SO3 and CaO, 3CaO·Al2O3·6H2O participated in the chemical reaction to produce high-sulfur hydrated calcium sulfoaluminate (ettringite), the volume of which increased by 1.5 times1. There was a sustained exothermic peak, and the temperature began to rise rapidly to 43.7℃, as shown in Fig. 4.

Based on Eq. 1, sufficient water and SO3 are beneficial for the formation and stability of the ettringite.

Under rigid confinement conditions such as concrete or rock, these crystallizations expand, squeezing each other and reducing porosity, thereby generating expansion pressure24. The mechanical properties of SCDA hydration products such as calcium hydroxide and ettringite depend on the confinement provided during SCDA volume expansion25. When ettringite begins to form in quantities that cause volume expansion, the constrained expansion pressure gradually increases. SEM images of SCDA at 6 h are shown in Fig. 5, depicting numerous needle-like ettringite crystals. A temperature rise can accelerate the SCDA hydration process, promoting the formation of dense ettringite and increasing expansion pressure26,27,28.

SCDA slurry expands slowly, causing initial micro-fracturing within the concrete. As expansion increases, internal micro-fracturing planes connect to form a macro-fracture, which finally propagates to the sample’s surface29. From this point onward, although the chemical reaction persists, the expansion agent expands freely without concrete constraint.

Expansion performance of cubic concrete tested by strain gauge

The curve of strain-time of strain gauge in different positions is shown in Fig. 6.

As shown in Fig. 6, it can be seen that the strain of the upper group strain gauge increased to 120µε before 4,740 s, then decreased suddenly. The strain of the D1-3 strain gauge increased slowly before 4,700 s. The strain of the D1 suddenly increased to 60,000µε at 4,778 s before the strain gauge failed. The strain of the D2 suddenly increased to 23,054.137µε at 4,838 s, after that the strain decreased to 7,000µε.

The strain of the D4 is negative, which indicates that this surface has been under compressive stress all the time. When expansion occurs at one location, squeezing stress is generated at the opposite location, causing the strain gauge show a negative value. The strain of the D4 remained negative throughout, indicating that position 2 underwent continuous expansion stress.

According to the engineering judgment criterion30: when the strain of the strain gauge exceeds 150µε and the difference between adjacent measurement points is greater than 50µε, concrete cracking can be judged.

Based on this judgment criterion, the cracking time of position D1 is judged as 4,736 s (78.9 min) at the strain of 644.597 µε.

The compressive strength of concrete was 42.07 MPa, so the concrete strength grade can be regarded as C40, and the elastic modulus of concrete can be selected as Es = 3.3 × 104 N/mm2.

If the concrete is in the elastic stage (without cracking), the calculated stress can be used directly. However, if the concrete develops micro-cracks or the strain gauge fails, the concrete has undergone nonlinear deformation. This causes the measured strain value to no longer accurately reflect the actual strain of the concrete. To more accurately estimate the internal stress state and prevent errors in structural safety judgment caused by overestimation, the elastic modulus needs to be corrected to a deformation modulus by multiplying a coefficient of 0.8531. So deformation modulus E’s = 0.85 × 3.3 × 104 N/mm2 = 2.81 × 104 N/mm2.

Based on σtm = εm E’s, the tensile stress at the break critical point can be calculated.

Thus, the tensile stress in the concrete induced by expansion pressure at this time can be calculated as 18.08 MPa, which is significantly greater than the concrete’s splitting tensile strength of 2.93 MPa.

Based on this judgment criterion, the cracking time of position D2 is 4,739 s (79 min) at the strain of 260.128 µε. The calculated tensile stress at the cracking time is 7.29 MPa which is greater than the concrete’s splitting tensile strength.

Expansion performance of cubic concrete tested by DOFS

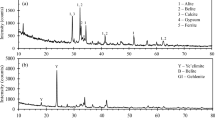

The strains at different times and positions, as measured by DOFS, are shown in Fig. 7. Because the Origin processing software can handle a maximum of 40 columns of data, and the expansion pressure did not appear significantly in the initial period of time, the strain at different positions at 37 time points before the crack appeared is used for plotting. The time interval between two adjacent curves is 100 s. Peak 9 corresponds the strain of upper optical fiber loop; Peaks 1–4 represent the strain of four sides of the waist, while Peaks 5–8 represent the strain of four corresponding positions of the upper surface.

Figure 7(a) shows the strain distribution measured by the nine-segment optical fibers on the concrete surface at different times. The first 4 peaks represent the strain of the four outer linear optical fibers, the next 4 peaks represent the strain of the four upper linear optical fibers, and the last one represents the strain of the upper optical fiber loop.

Figure 7(b) shows that when the distance between the loop optical fiber and the hole is the same, the strain is essentially consistent, and the early curve being nearly linear with a fluctuation range of approximately 30µε.

Figure 7(b)-(j) show that the strain at the middle position is the greatest and gradually decreases toward both ends. The strain distributions of Peak 1 and Peak 6 exhibit standard triangular peak patterns, which align with classical structural mechanics principles. Fluctuations exist among the four peaks of the waist or upper surface, with some showing bifurcations or asymmetry. These variations are attributed to unevenness in the concrete surface or unequal distances from SCDA slurry. By comparing peak1 with peak 5, peak 2 with peak6, peak 3 with peak 7, and peak 4 with peak 8, it can be seen that the strain distribution in the optical fibers at the four positions on the upper surface is greater than that at the four corresponding positions on the outer surfaces.

The location of the cracking on any of the four surfaces is related not only to the stress distribution but is also significantly influenced by the quality of the concrete on that surface. If there are micro-pores or micro-cracks in the concrete on a given side, cracking may occur on that side even if the expansion tensile stress is lower than that on the other three sides. When the first surface cracked, the other surfaces crack sequentially, and their expansion tensile stress are all lower than that of the first surface, because the cracking of the first surface led to the partial stress release in the other surfaces.

According to the engineering judgment criterion, the cracking time of 9-segment optical fiber are judged and their corresponding strains, as listed in Table 1.

Therefore, the cracking times are determined as follows: 4500 s for the optical fiber on outer surface, 4,400 s for the optical fiber on upper surface, and 4,700 s for loop optical fiber. Accordingly, the minimum cracking time of a 150-mm cubic concrete is evaluated as 4,400 s (73.3 min), and its corresponding strain is 400.43µε, which shows the tensile stress on the concrete’s outer surface is calculated to be 11.25 MPa.

From the upper surface, only the trend of strain variation with distance can be obtained. There is a discrepancy between the surface strain and the actual internal strain because the expansion pressure propagates from the center to the periphery. However, to calculate the actual internal expansion force, the external expansion must have a clear physical meaning32. Therefore, it is more reasonable to perform calculations based on the average expansion strain of the four surfaces.

Comparison of cracking time judged by three test methods

The comparison of cracking time on concretes judged by DOFS, strain gauge and crack width were 4,400 s, 4,736 s and 5,040 s, respectively.

The cracking time judged by DOFS was 336 s earlier than that by the strain gauge, and 640 s earlier than that by the crack width. This is because some strain gauges are not positioned along the crack path and can only reflect the conditions of an entire surface, whereas DOFS can detect deformation at specific points on whole surface, offering higher accuracy and the ability to locate the cracks precisely. In addition, the elastic modulus of optical fiber (Polyimide coating) is 72 GPa, while the strain gauge is made of alloy steel with an elastic modulus of approximately 200 GPa, which is about three times that of optical fiber. Consequently, the deformation sensitivity of DOFS is much higher than that of the strain gauge. The width of a crack visible to the naked eye is typically 0.1 mm33, so it is hard to monitor the concrete to observe this crack, with significant judgement errors.

Analysis of the relationship between expansion strain with time and distance from the hole

Based on data of the positions judged as crack initiation, the strain-time curves are plotted in Fig. 8, which demonstrate a good correlation between the strain development and the time.

As shown in Fig. 8, based on the strain data within the range of 1,000 s to 4,300 s before cracking, the relationships between strain (S) and time (T) of Peak 2, Peak 5, and Peak 9 are fitted as follows:

Peak 2: S = 0.0881T − 101.38; R2 = 0.945 (Distance = 55 mm).

Peak 5: S = 0.1034T − 120.94; R2 = 0.9136 (Distance = 30 mm).

Peak 9: S = 0.0826T − 93.429; R2 = 0.9474 (Distance = 20 mm).

All R2 are more than 0.91, which indicates that they all have linear relationships between the strain and time at different distances from the hole. The slope of the line represents the strain growth rate of the peak, with units per 100 s.

The hydration of SCDA causes expansion. Under the constraints of concrete, this expansion leads to strain of the concrete. The expansion pressure generated by SCDA is affected by factors such as the crystallization process, internal porosity, and temperature9; therefore, it is a variable value that initially increases and subsequently decreases. If the expansion pressure of SCDA at different times is simulated by controlling water pressure34, it would not only verify the accuracy of DOFS strain testing but also improve the study of concrete cracking behavior induced by SCDA.

When the optical fiber is annular, the average strain at 3,000 s is calculated as 153.56µε; and its calculated expansion tensile stress is 4.32 MPa. When optical fibers are straight, the average strain of 10 measurement points at the midspan position at 3,000 s is calculated for Peak 5 and Peak 7 as 97.59µε and 125.49µε, respectively, and their calculated expansion tensile stresses are 3.52 MPa and 4.31 MPa. All calculated expansion tensile stresses exceed the concrete splitting tensile strength of 2.93 MPa.

On the same top surface, at 3,000 s before concrete cracks, the average strain of the cubic concrete are 153.56µε and 125.49µε at two distances (20 mm and 30 mm). The relationship between strain (S) and distance (D) is fitted as:

Based on Eq. 3, there is a negative correlation between the strain with the distance from the hole, which is consistent with the conclusion obtained in Fig. 3.

According to the thin-wall theory35,36,37, when the average expansion tensile stress generated by the expansion pressure on the surface of a concrete ring specimen exceeds the concrete’s tensile strength, the concrete will crack. The average expansion tensile stress is related to concrete strength, pore size ratio, and other factors. Therefore, with known concrete strength and size, effective cracking and crushing can be achieved by optimizing the borehole spacing.

Conclusions

-

(1)

As SCDA hydrates, the temperature of slurry rises to a peak and then gradually decreases.

-

(2)

To evaluate the strain and cracking time of concrete, DOFS exhibits greater accuracy and sensitivity than both static strain testers and naked-eye crack defect testers.

-

(3)

Using DOFS technology, the cracking time of a 150 mm C40 cubic concrete under pressure from SCDA in the central hole (40 mm in diameter) is evaluated as 73.3 min. The strain-position peak shapes at different times align with classical structural mechanics principles, and there is a linear correlation between strain and time, but a negative correlation with distance from the hole.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

De Silva, V. R. S., Ranjith, P. G. & Perera, M. S. A. An alternative to conventional rock fragmentation methods using SCDA: a review. Energies 9 (11), 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/en9110958 (2016).

Zhang, Y. L., Pan, Y. F., Ren, T. Z. & Zhang, J. F. Research progress in the application of calcium-based expansive agents as compensation for autogenous shrinkage in high-strength concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. e03685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03685 (2024).

Xiao, J. et al. Mechanism of chloride ion transport and associated damage in ultra-high-performance concrete subjected to hydrostatic pressure. J. Building Eng. 112, 113700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113700 (2025).

Weng, R. C. et al. Shear performance of UHPC-NC composite structure interface treated with retarder: quantification by fractal dimension and optimization of process parameters. Buildings 15 (15), 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152591 (2025).

Cho, H., Nam, Y. & Kim, K. Numerical simulations of crack path control using soundless chemical demolition agents and Estimation of required pressure for plain concrete demolition. Mater. Struct. 51, 169. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-018-1292-y (2018).

Sun, L. Q. et al. Contribution of soundless chemical demolition and induction heating demolition to carbon emissions reduction in urban demolition industry. Energy Build. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113671 (2023). .300,113671.

Zhang, H., Xing, X. & Du, Y. Experimental study on the Spatiotemporal effects of blasting dynamic–static action in decoupling charge. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 58, 3113–3128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-04308-4 (2025).

Li, R. S. et al. Synergistical influence of internal expansion and external constraint on demolition efficiency of soundless chemical demolition method for concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134194 (2023).

Li, C., He, S. F., Hou, W. T. & Ma, D. Experimental study on expansion and cracking properties of static cracking agents in different assembly States. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32 (6), 1259–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2022.09.001 (2022).

Wang, L., Duan, K. & Zhang, Q. Study of the dynamic fracturing process and stress shadowing effect in granite sample with two holes based on SCDA fracturing method. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 55, 1537–1553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02728-0 (2022).

Li, R. S., Yan, Y., Jiang, Z. S., Zheng, W. Z. & Li, G. C. Impact of hole parameters and surrounding constraint on the expansive pressure distribution and development in soundless chemical demolition agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 307, 124992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124992 (2021).

Tang, W. et al. The influence of borehole arrangement of soundless cracking demolition agents (SCDAs) on weakening the hard rock. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31 (2), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.01.005 (2021).

Wang, J. L. et al. 3D crack propagation in concrete induced by soundless cracking demolition agents. Eng. Fract. Mech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110135 (2024). 306,110135.

Jiang, Z., Zheng, W., Li, S., Sun, L. Q. & Xu, C. H. Equation of hole arrangement for concrete beam demolition using soundless chemical demolition agent. J. Building Eng. 45, 103311–103321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103311.( (2022).

Habib, K. M., Vennes, I. & Mitri, H. Laboratory investigation into the use of soundless chemical demolitions agents for the breakage of hard rock. Int. J. Coal Sci. Techno. l9, 70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00547-4 (2022).

Jiang, Z. S. et al. The Use of soundless chemical demolition agents in reinforced concrete deep beam demolition: experimental and numerical study. Journal of Building Engineering 69, 106260 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe (2023).

Zhang, W., Guo, W. Y. & Wang, Z. Q. Influence of lateral pressure on mechanical behavior of different rock types under biaxial compression. J. Cent. South. Univ. 29, 3695–3705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-022-5196-1 (2022).

Kim, K., Cho, Hwangki, S. & Lee, D. Jaeha. The use of expansive chemical agents for concrete demolition: example of practical design and application. Constr. Build. Mater. 272, 121849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121849 (2021).

Zhang, Q. H. et al. Transform based method for monitoring the crack of concrete arch by using FBG sensors. Optik 127 (6), 3417–3422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2015.12.087 (2016).

Huang, X. et al. Research on horizontal displacement monitoring of deep soil based on a distributed optical fibre sensor. J. Mod. Opt. 65 (2), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340.2017.1382594 (2017).

Zhang, Q. H. et al. Strain Tranfer in distributed fiber opic sensor with optical frequency domain reflectometry technology. Opt. Eng. 58 (2), 027109. https://doi.org/10.1117/1OE.58.2.027109 (2019).

Chen, X. D., Shi, D. D., Zhang, J. H. & Cheng, X. Y. Experimental study on loading rate and notch-to-depth ratio effects on flexural performance of self-compacting concrete with acoustic emission and digital image correlation technologies. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 56 (3), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309324720949002.( (2021).

Shi, D. D. et al. Wu C.G. Experimental study on post-peak Cyclic characteristics of self-compacting concrete combined with AE and DIC techniques. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 18 (7), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.3151/jact.18.386.( (2020).

De Silva, V. R. S., Ranjith, P. G., Perera, M. S. A., Wu, B. & Rathnaweera T.D. Investigation of the mechanical, microstructural and mineralogical morphology of soundless cracking demolition agents during the hydration process. Mater. Charact. 130, 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2017.05.004 (2017).

Manatunga, U. I., Ranjith, P. G. & De Silva, V. R. S. Modified non-explosive expansive cement for preconditioning deep host rocks: A review. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ Geo-resour. 7, 99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-021-00292-z (2021).

Gui, Y. T., Jiang, Z. M., Dai, C. Y. & Zhang, Q. B. Enhanced effect of self-propagating subsequent heating on the expansive pressure on soundless chemical demolition agent. Constr. Build. Mater. 364, 129866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129866 (2023).

Debra, F., Laefer, A. S., Natanzi, S. M., Iman & Zolanvari Impact of thermal transfer on hydration heat of a soundless chemical demolition agent. Constr. Build. Mater. 187, 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.168 (2018).

Jia, F., Yao, Y. & Zhao, S. Experimental study on thermal stress of concrete with different expansive minerals using a temperature stress testing machine. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. -Mat Sci. Edit. 37, 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11595-022-2521-3 (2022).

Zhao, X. L., Huang, B. X. & Cheng, Q. Y. Experimental investigation on basic law of rock directional fracturing with static expansive agent controlled by dense linear multi boreholes. J. Cent. South. Univ. 28, 2499–2513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-021-4782-y (2021).

Manatunga, U. I., Ranjith, P. G. & De Silva, V. R. S. Evaluation of slow-releasing energy material (SREMA) injection for in-situ rock breaking under uniaxial and triaxial loading: an experimental study. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57, 7879–7903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03938-y (2024).

Stéphane Multon, F. Effect of applied stresses on alkali-silica reaction-induced expansions. Cem. Concr. Res. 36 (5), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.11.012 (2006).

De Silva, V. R. S., Ranjith, P. G. & Perera, M. S. A. The influence of admixtures on the hydration process of soundless cracking demolition agents (SCDA) for fragmentation of saturated deep geological reservoir rock formations. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 52, 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1596-9 (2019).

Emilia Vasanelli, D., Colangiuli, A., Calia, Vincenza, A. M. & Luprano Estimating in situ concrete strength combining direct and indirect measures via cross validation procedure. Constr. Build. Mater. 151, 916–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.06.141 (2017).

Chen, J. H., Li, Y. L., Wen, L. F., Bu, P. & Li, K. P. Experimental study on axial compression of concrete with initial crack under hydrostatic pressure. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 24 (2), 612–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-5369-0 (2020).

36, Sakhno, I. & Sakhno, S. Directional fracturing of rock by soundless chemical demolition agents. Heliyon 10, e26068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26068 (2024).

37, Xu, S., Hou, P. Y., Li, R. R. & Suorineni Fidelis, T. An improved outer pipe method for expansive pressure measurement of static cracking agents. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32 (1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.11.011 (2022).

38, De Silva, V. R. S., Konietzky, H. & Mearten, H. A hybrid approach to rock pre-conditioning using non-explosive demolition agents and hydraulic stimulation. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56, 7415–7439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03455-4 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources, data curation, writing-original draft preparation and editing were done by M.H. Liu. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M. Experimental study on concrete expansion performance and cracking time under SCDA pressure using DOFS technology. Sci Rep 15, 42625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26826-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26826-z