Abstract

Soil salinity impairs the growth, development, and the yields of the crops and contribute to increased agriculture productivity. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) help plant growth and mitigate soil salinity. The present study aimed to isolate multifarious rhizobacteria to simultaneously mitigate salinity stress and improve growth and physiological traits in black cumin. The study revealed the effects of Bacillus subtilis IGPEB 1, Bacillus altitudinis IGPEB 8, Bacillus endophyticus IGPEB 33, and Pseudomonas koreensis IGPEB 17 on the growth and physiological properties of Nigella sativa L. under salt stress. The results revealed that B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. endophyticus IGPEB 33, and B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 significantly increased the shoot length by 20.96% and 26.73% and total root length by 73.15%, respectively. B. endophyticus IGPEB 33 (T4) significantly enhanced total root length by 103.66%, projected area by 36.67%, and root surface area by 50.78%, respectively. Application of B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 (T3) and B. endophyticus IGPEB 33 (T4) enhanced total chlorophyll content by 73.36% and 85.51%, chlorophyll a by 74.46% and 80.00%, chlorophyll b by 66.66% and total chlorophyll by 45.71% and carotenoid contents by 55.55% and 79.62%, respectively, the antioxidant capacity, antioxidant enzymes’ activities and relative water content of leaves by 8.25% and 9.07% compared to the control. The consortium of B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 and B. endophyticus IGPEB 33 positively influences physiological properties in Nigella sativa L. under salt stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

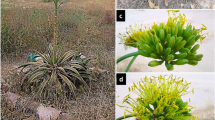

Nigella sativa L. is a plant that comes from dry and semi-arid areas. In the Ranunculaceae family, Nigella sativa L. is an annual herb that is native to several countries in southern Europe and Asia, including Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia, India, and Pakistan1. Nigella sativa L. has been recommended in various conventional medical practices, including Unani, Ayurveda, and Tibb. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, and hepatoprotective properties of Nigella sativa L. make it a medicinally important plant2,3. The essential oil of Nigella sativa L. contains medicinally important and pharmacologically important compounds such as thymoquinone (TQ), carvacrol, nigellidine, nigellicine, and hederin4. It is also vital that nutraceuticals, as their components, support the immune system5.

However, cultivation of this vital crop is affected by soil salinity6. When excessive fertilizer is applied to the soil, crop production is lost, and the soil becomes highly salinized7,8. To withstand excess salt ions, plants undergo biochemical and physiological changes9,10. Moreover, the enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes reduces the damage caused by ROS due to salinity stress11. The regulation of these physiological and biochemical processes is based on the activities of the crop microbiome. Salinity may negatively affect the growth, yield, and physiological processes of Nigella sativaL12,13,14,15..

Additionally, it has been observed that farming methods significantly impact crop growth in saline soils15. Ploughing down or tilling more deeply increases evaporation of soil water, leaving behind excess salts. Additionally, salts in irrigation water can increase soil salinity, thereby reducing productivity16. Traditional physical and chemical methods of salinity mitigation have certain limitations17. To ensure sustainable agricultural production on saline soils, sustainable measures should be employed alongside salt-tolerant plant varieties and chemical neutralization techniques18. Recent studies have demonstrated that plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) can mitigate salinity while boosting soil fertility and crop yield19,20. PGPR works by fixing nitrogen, producing phytohormones, enzymes, and solubilizing minerals to enhance plant growth under biotic and abiotic stresses21,22,23,24,25. Thus, PGPR can convert unfertile soils to fertile soils, thereby enhancing plant adaptation to various biotic and abiotic stresses26,27,28. Overall, PGPR as biofertilizers offers an affordable and environmentally acceptable method to improve crop growth and yield under salinity stress, making them a practical and necessary tool to support sustainable agriculture. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of PGPR on the growth and physiological properties of Nigella sativa L. in saline soil. We hypothesize that inoculating salt-tolerant PGPR could improve the growth, morphological traits, and physiological properties of Nigella sativa L. in saline soil.

Methods

Soil and plant growth-promoting bacteria

Saline soil collected from the Surkhandaryo Region (Kumkurgan District), Uzbekistan (37.8208° N, 67.6007° E), was used in the present study. Bacillus subtilis IGPEB 1, Bacillus altitudinis IGPEB 8, Bacillus endophyticus IGPEB 33, and Pseudomonas koreensis IGPEB 17, obtained from the Institute of Genetics and Plant Experimental Biology in Tashkent, were employed as PGPR. These cultures were grown in a nutrient broth containing 3 g beef extract, 5 g peptone, and 1000 mL of water. Black cumin (Nigella sativa L.) seeds were obtained from Tashkent Botanical Garden, named after the Academy. F.N. Rusanov of the Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan. N. sativa L. seeds were bacterized with a fresh culture of PGPR (5 × 107 cells/mL), followed by air-drying and sowing in pots. All treatments were replicated five times. Forty days after sowing (DOS), plant height, fresh weight of shoot, fresh weight of root, and photosynthetic pigments were measured.

Measurement of root morphological traits of Nigella sativa L

The water-washed root system was analyzed using a scanning system (Expression 4990, Epson, CA), and the digital images were analyzed to measure the total root length, the root surface area, the root volume, the projected area, and the root diameter using Win RHIZO software (Régent Instruments, Québec, Canada).

Physiological parameters measurement

The total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents in Nigella sativa L. were measured according to the methods of Havaux and Kloppstech30 using the following equations –

.

Measurement of relative water content

The relative water content of the leaves was measured using the Barrs and Weatherly method31. 30 to 100 mg of fully expanded was incubated in double-distilled water for four h at 28 °C, and the fresh weight was. The leaf was removed, blotted dry, and its turgid weight (TW) was recorded. After that, the samples were oven-dried at 70 °C overnight, and the dry weight (DW) was recorded. RWC was calculated as follows-

Measurement of total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

Total antioxidant capacity was measured according to the method of Prieto et al.32. A 0.1 mL mixture of 0.6 M sulphuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate was incubated at 95 °C for 90 min, cooled, and then the absorbance was measured at 695 nm against a blank containing ascorbic acid. The TAC was calculated from the calibration curve of ascorbic acid using the following linear equation and expressed as µg of ascorbic acid equivalent per mL of extract (µg AAE/mL)

Where,

Y is the absorbance at 695 nm.

X is the concentration of ascorbic acid (µg/mL).

Measurement of antioxidant enzymes

For screening of antioxidant enzymes, namely, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione oxidase (GSH), and peroxidase (PO), and stress-relieving enzyme ACC deaminase (ACCD), each isolate was separately grown in each minimal medium (MM) at 30◦C for 24 h at 120 rpm. Following 24 h of incubation, each broth was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min to obtain a cell homogenate.ACCD activity was assayed according to the Honma and Smmomura method33. The number of mM of α-ketobutyrate produced by this reaction is determined by comparing the absorbance at 540 nm of a sample to a standard curve of α-ketobutyrate (0.1mM-1.0 mM).

For SOD activity, a 100 µL cell homogenate was mixed with 100 µL pyrogallol in EDTA buffer (pH 7.0), and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm34. One unit of SOD is defined as the amount of SOD required for preventing 50% auto-oxidation of pyrogallol.

For measuring CAT activity, 100 µL of cell homogenate was mixed with 100 µL of H2O2 in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the absorbance was measured at 240 nm35. One unit of CAT is defined as the amount of mM of H2O2 decomposed per minute.

For measuring GSH activity, 100 µL of cell homogenate was mixed with 100 µL of GSH in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the absorbance was measured at 240 nm36. GSH activity was measured as the reduction in µM of GSH per min.

For measuring POD activity, 100 µL of cell homogenate was mixed with 4 µL 4-methylcatechol in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). POD activity was taken as an increase in the absorbance at 420 nm resulting from the oxidation of 4-methyl catechol by H2O2. Under assay conditions, one unit of enzyme activity is defined as a 0.001 change in absorbance per min37.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. A one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) was used to determine the level of significance (p < 0.05). The values were compared to assess differences in the effects of various treatments on the morphological and physiological properties of Nigella sativa L. The heat map was created using MetaboAnalyst 6.0.

Results

Plant growth parameters of Nigella sativa L

The effects of PGPR on some plant growth parameters under saline soil were investigated. B. endophyticus 33 treatment enhances the shoot length (cm) by 9.67 ± 0.40, the fresh weight of the shoot (cm) by 0.68 ± 0.03, and the fresh weight (cm) of the root by 0.39 ± 0.01 compared to B. subtilis IGPEB 1, P. koreensis IGPEB 17 treatments, and control, as shown in Table 1. Treatment of B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 shoot length 9.23 ± 0.35, 0.65 ± 0.02 fresh weight of shoot, and 0.37 ± 0.02 fresh weight of root compared to B. subtilis IGPEB 1, P. koreensis IGPEB 17, and control. Treatment of B. subtilis IGPEB 1 enhances the shoot lengths 8.30 ± 0.10, fresh weight of shoot 0.51 ± 0.03, and fresh weight of root 0.29 ± 0.02 compared to the control.

B. endophyticus 33 treatment maximizes Nigella sativa L. root morphological traits in saline soil compared to B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. subtilis IGPEB, P. koreensis IGPEB 17, and control. Root diameter (mm) 0.45 ± 0.05, root volume (cm3) 0.35 ± 0.05, root surface area (cm2) 9.65 ± 0.21, projected area (cm2) 7.90 ± 0.29, and total root length (cm) 76.03 ± 1.61 when treated with B. endophyticus 33. Table 2 represents the root morphological traits of Nigella sativa L. under saline soils. Treated with B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, the root diameter (mm) was 0.45 ± 0.05, root volume (cm3) was 0.35 ± 0.05, root surface area (cm2) was 8.44 ± 0.41, projected area (cm2) was 7.78 ± 0.95, and total root length (cm) was 64.64 ± 4.29 compared to the control. B. subtilis IGPEB 1treatment the root diameter (mm) 0.41 ± 0.03, root volume (cm3) 0.32 ± 0.05, root surface area (cm2) 7.97 ± 0.28, projected area (cm2) 6.42 ± 0.32, and total root length (cm) 54.94 ± 6.86.

Physiological properties of Nigella sativa L

The chlorophyll a content (mg/g) increased when treated with B. endophyticus 33 and B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 compared to B. subtilis IGPEB 1, P. koreensis IGPEB 17, and control. No significant (chlorophyll a content) difference between B. endophyticus 33 and B. altitudinis IGPEB 8. Treatment with B. subtilis IGPEB 1 chlorophyll a content (mg/g) increased compared to the P. koreensis IGPEB 17 and control. P. koreensis IGPEB 17 treatment increased the chlorophyll a content compared to the control. Chlorophyll b content is maximum with B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 treatment compared to P. koreensis IGPEB 17, B. endophyticus 33, B. subtilis IGPEB 1 treatments, and control. P. koreensis IGPEB 17 treatment showed a significant difference in chlorophyll b content compared to the B. endophyticus 33, B. subtilis IGPEB 1 treatment, and control. B. endophyticus 33 showed a significant increase in chlorophyll b content compared to the B. subtilis IGPEB 1 treatment and control (Fig. 1).

T1- Control, T2- B. subtilis IGPEB 1, T3- B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, T4- B. endophyticus 33, T5- P. koreensis IGPEB 17.

Values are the average of triplicates (n = 3). + = standard deviation. Different letters indicate significant values at p < 0.05. The values were compared to assess differences in the effects of various treatments on photosynthetic pigments in N. sativa L.

The maximum content of total chlorophyll by B. altitudinis IGPEB8 and B. endophyticus 33 treatments compared to P. koreensis IGPEB17 and B. subtilis IGPEB1, concerning the control. P. koreensis IGPEB17 and B. subtilis IGPEB1 treatments showed no significant difference in total chlorophyll content, but a significant difference compared to B. altitudinis IGPEB8, B. endophyticus 33, and the control. The total carotenoid content (mg/g) increased by the B. endophyticus 33 treatment compared to the B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. subtilis IGPEB 1, P. koreensis IGPEB 17 treatments, and control (Fig. 1). B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 treatment produces more carotenoid content than the B. subtilis IGPEB 1, P. koreensis IGPEB 17 treatments, and the control.

The relative water content of the leaf increased when treated with B. endophyticus 33, B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. subtilis IGPEB 1, and P. koreensis IGPEB 17 compared to the control, as shown in Fig. 2a. No significant differences in RWC were recorded between B. endophyticus 33, B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. subtilis IGPEB 1, and P. koreensis IGPEB 17.

T1- Control, T2- B. subtilis IGPEB 1, T3- B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, T4- B. endophyticus 33, T5- P. koreensis IGPEB 17. Values are the average of triplicates (n = 3). + = standard deviation. Different letters indicate significant values at p < 0.05. The values were compared to assess differences in the effects of various treatments on the relative water content of N. sativa L.

The leaf water storage increased when treated with B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, B. endophyticus 33, and P. koreensis IGPEB 17 compared to the B. subtilis IGPEB 1 and control treatments (Fig. 2b). B. subtilis IGPEB 1 treatment significantly differed from the control in leaf water storage.

The effects of plant growth-promoting bacteria on growth parameters, root morphological traits, and physiological properties of Nigella sativa L. under saline soil were analyzed using a heat map and clustering (Fig. 3). Figure 3 indicates the differences between the morphological and physiological traits of inoculated and uninoculated plants. From the dendrogram, it was analyzed that the treatments were categorized into three classes: untreated control, with the least effect; plants treated with B. subtilis IGPEB 1 and P. koreensis IGPEB 17, which showed a better impact on growth promotion; and B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 and B. endophyticus 33-treated plants, which showed the most noticeable results. T3 and T4 were the most effective treatments, showing the most significant growth promotion and increases in physiological and biochemical traits. All treatments were significantly different from one another, indicating that each bacterium had a distinct effect on Nigella sativa L. growth.

T1 − Control (uninoculated), T2 − B. subtilis IGPEB 1, T3 − B. altitudinis IGPEB 8, T4 − B. endophyticus 33, T5 − P. koreensis IGPEB 17.

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of Nigella sativa L

All the treatments (except the control) improved the levels of antioxidant enzymes in plant leaves. However, treatments T3 and T4 yielded maximum TAC (13.60 ± 0.18 and 12.92 ± 0.11 AAE/mL) compared to the control (7 ± 0.11 AAE/mL) (Table 3).

Antioxidant enzymes of N. sativa L

The highest ACCD activity was observed in the T3 and T4 treatments (0.59 ± 0.03 and 0.62 ± 0.02 nM α-ketobutyrate mg protein/h, respectively) compared with other treatments (Table 3). ACCD activities of these treatments were 18% and 22%, respectively, higher than in the control.

All the treatments (except the control) improved the levels of antioxidant enzymes in plant leaves. However, Treatment T3 and T4 significantly enhanced the activities of SOD, CAT, GSH, and POD. Treatment T3 and T4 revealed SDO activity of 21.22 ± 0.03 and 22.01 ± 0.03 IU/mg, CAT activity of 2.011 ± 0.02 and 1.99 ± 0.02 mM of H2O2 decomposed/min, GSH activity of 31.97 ± 0.01 and 32.03 ± 0.01µM GSH reduced/min, and POD activity of 11.97 ± 0.01 and 12.03 ± 0.01 µg/mL (Table 3). SOD, CAT, SGH, and POD activities were significantly higher by 24%, 29%, 27%, and 31%, respectively, over the control.

Discussion

Plant salt uptake indirectly affects plant growth, as it first influences turgor state and photosynthesis, and simultaneously impacts enzyme activity, as well as morphological, physiological, and biochemical processes38,39. The accumulation of salt ions in old leaves accelerates cell death and hinders the transport of carbohydrates and growth hormones to growth tissues. Excessive accumulation of salt ions hinders plant growth by reducing photosynthetic rate and generating growth-inhibiting metabolites. Earlier reports have shown the negative impacts of salinity on plant growth15,40,41.

The growth and health of crop plants rely on adequate amounts of essential nutrients. The crop microbiome plays a pivotal role in supplying these nutrients to its host plants. Crop microbiomes secrete a diverse array of plant-beneficial traits to enhance plant growth42. A broad range of PGPR, including Bacillus spp., has been identified for its role in promoting plant growth under both normal and saline stress conditions. Using PGPR under saline circumstances is a promising method of increasing crop productivity. PGPR interacts with plant roots and has both direct and indirect favorable effects on plant growth and the reduction of biotic and abiotic stressors43.

Khan and Kunuc13 reported the adverse effects of soil salinity and salinity levels on plant height, vegetative dry weight, and oil content of black cumin. They further found that soil salinity and dits levels reduce the number of capsules and seed weight. Douka et al.44 found that endophytic PGPR exert beneficial effects on the health of black cumin. They isolated endophytic Bacillus halotolerans from N. sativa leaves, which demonstrated multiple plant growth-promoting traits that support plant growth, colonization, and tolerance to abiotic stress. Darekh et al.45 reported a substantial increase in chlorophyll a content in N. sativa following inoculation with Pseudomonas fluorescens.

Chlorophyll content in leaves is an indicator of salt tolerance and also plays a role in responding to increased salinity46. In the present study, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and total carotenoid contents of the leaf increased following the inoculation with PGPR compared to the control. Accordingly, several studies have shown that inoculation with PGPR increases plant growth and chlorophyll content under salt stress conditions47,48,49. The PGPR can enhance photosynthetic pigments by increasing photosynthetic potential and facilitating the absorption of water and ions50. On the other hand, the inoculated salt-stressed coriander plants showed higher chlorophyll content and dark-green leaves due to the presence of ACC deaminase-producing PGPR51. ACCD activity helps plants withstand salinity and other stress conditions while promoting growth and development41. PGPR significantly improves the photosynthetic pigments, such as chlorophyll and carotenoid content, of plants under various saline soil conditions52,53,54,55,56,57.

Kusale et al.58,59 observed a negative impact of excess salt on wheat growth in saline soil, reporting substantial reductions in root length, shoot height, and chlorophyll content in wheat seedlings after 40 days of salinity stress. However, they noted that the inoculation of halophilic Klebsiella sp. mitigated this adverse effect and significantly improved plant growth parameters, such as root length, shoot length, and chlorophyll content, in wheat60.

Abiotic stress negatively affects plant growth, root morphological traits, and physiological properties of different plants61,62,63,64. The PGPR treatment increased the relative water content and leaf water storage compared to the control. Inoculation with PGPR improved growth yield and plant-water relations, consequently enhancing quinoa yield. Salinity reduces the plant’s water content and causes the buildup of excess ions, thereby lowering the osmotic potential66.

Soil salinity affects plant growth and development, reducing crop yield. Plants often adapt to salt stress through the metabolic activities of their PGPR. The interplay of metabolites from PGPR induces biochemical and physiological changes in plants, enabling them to withstand salinity stress67. There are various mechanisms, both direct and indirect, by which PGPR improve plant growth, nutrient content, and antioxidant capacities under salt-stressed conditions58,59,68.

Many PGPR improve total antioxidant capacity by producing a wide range of antioxidant enzymes69, which protect plants from oxidation70. Kapadia et al.67 isolated halophilic Bacillus halotolerans from the saline soil of Dandi, India, and reported the production of various antioxidant enzymes under salt stress, which improved tomato growth under salinity.

ACC deaminase-producing PGPR is vital in withstanding plant stress conditions and helps plants grow in the presence of excess salt71. Consequently, the production of ACCD reduced ethylene concentration, which exhibits ROS activity. The enzyme ACCD reduces ACC levels in root exudates, thereby preventing excessive ethylene accumulation in plant roots and promoting better root growth and length. Plants with longer root lengths absorb more nutrients67,72. The effect of Pseudomonas entomophila PE3 on growth parameters and physiological traits, and on salinity stress in sunflowers under saline conditions was studied by Fatima and Arora73. They reported that Pseudomonas entomophila PE3 enhances plant growth, physiological characteristics, and salinity-stress tolerance. Moradzadeh et al.74 and Devkot et al.75 observed higher oil and macronutrient contents in Nigella sativa L. and other crops following inoculation with rhizobacteria and the application of biochemical fertilizers76,77,78. Plant growth-promoting bacteria enhance the growth and physiological characteristics of plants under saline conditions79,80,81,82.

The widespread use of agrochemicals to increase crop yields has harmed water supplies, agricultural soils, beneficial organisms, human health, and the ecosystem. PGPR, which encompasses numerous bacterial species, can effectively enhance growth characteristics and yield under various conditions by mitigating multiple abiotic factors76,81,83. Plants benefit from PGPR in various physiological activities, including the solubilization of mineral nutrients and the production of phytohormones83. The inoculation of Nigella sativa L. plants with B. endophyticus IGPEB33 and B. altitudinis IGPEB8 had essential impacts on the tolerance of Nigella sativa L. to salinity stress. Our results suggest that salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacterial strains B. endophyticus IGPEB 33 and B. altitudinis IGPEB 8 can be applied to mitigate the effects of salinity stress while improving the growth and yield of Nigella sativa L.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hannan, M. A. et al. Black Cumin (Nigella sativa L.): A comprehensive review on phytochemistry, health benefits, molecular pharmacology, and safety. Nutrients 13 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061784 (2021).

Majeed, A. et al. Nigella sativa L.: uses in traditional and contemporary medicines–An overview. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41 (4), 253–258 (2021).

Manoharan, N., Jayamurali, D., Parasuraman, R. & Govindarajulu, S. N. Phytochemical composition, therapeutical and Pharmacological potential of Nigella sativa: A review. Traditional Med. Res. 6 (4), 32 (2021).

Ravi, Y. et al. Identification, validation, and quantification of thymoquinone in conjunction with assessment of bioactive possessions and GC-MS profiling of pharmaceutically valuable crop Nigella (Nigella sativa L.) varieties. PeerJ 12, e17177 (2024).

Mahboub, H. H. et al. Dietary black Cumin (Nigella sativa) improved hemato-biochemical, oxidative stress, gene expression, and immunological response of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) infected by burkholderia Cepacia. Aquaculture Rep. 22, 100943 (2022).

Mishra, A. K. et al. Promising management strategies to improve crop sustainability and to amend soil salinity. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 962581 (2023).

Cheng, M. et al. Crop yield and water productivity under salty water irrigation: A global meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manage. 256, 107105 (2021).

Farooqi, Z. U. R. et al. Management of soil degradation: A comprehensive approach for combating soil Degradation, food Insecurity, and climate change. Ecosystem Management: Clim. Change Sustain., 55–78 (2024).

Hao, S. et al. A review on plant responses to salt stress and their mechanisms of salt resistance. Horticulturae 7 (6), 132 (2021).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (17), 9326 (2021).

Hamidian, M. et al. Co-application of mycorrhiza and Methyl jasmonate regulates morpho-physiological and antioxidant responses of crocus sativus (Saffron) under salinity stress conditions. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 7378. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34359-6 (2023).

Sharifi, P. & Shirani Bidabadi, S. Protection against salinity stress in black Cumin involves Karrikin and calcium by improving gas exchange attributes, ascorbate–glutathione cycle, and fatty acid compositions. SN Appl. Sci., 2(12) (2020).

Khan, A. & Kurunc, A. Effects of salt source and irrigation water salinity on growth, yield, and quality parameters of black Cumin. Irrig. Sci. 72 (3), 823–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.2816 (2023).

Kurunc, A. H., Tezcan, N. Y. & Khan, A. Determination of salt stress by plant leaf temperature and thermal imaging in black Cumin grown under different salt sources. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 21;56(4), (2025). 517 – 27.

Al-Turki, A., Murali, M., Omar, A. F., Rehan, M. & Sayyed, R. Z. Exploring the recent advances in PGPR-mediated resilience towards interactive effects of drought and salt stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1214845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1214845 (2023).

Jabborova, D. et al. Biochar improves the growth and physiological traits of alfalfa, amaranth, and maize grown under salt stress. PeerJ 11, e15684 (2023).

Ondrasek, G. & Rengel, Z. Environmental salinization processes: Detection, implications and solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 754, 142432 (2021).

Khan, P. A. et al. Valorization of coconut shell and blue berries seed waste into enhance bacterial enzyme production: Co-fermentation and co-cultivation strategies. Indian J. Microbiol. 65, 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-025-01446-3 (2025).

Shabaan, M. et al. Salt-tolerant PGPR confers salt tolerance to maize through enhanced soil biological health, enzymatic activities, nutrient uptake, and antioxidant defense. Front. Microbiol. 13, 901865 (2022).

AbuQamar, S. F. et al. Halotolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria improve soil fertility and plant salinity tolerance for sustainable agriculture—A review. Plant. Stress. 12, 100482 (2024).

Sethi, G. et al. Enhancing soil health and crop productivity: the role of zinc-solubilizing bacteria in sustainable agriculture. Plant. Growth Regul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-025-01294-7 (2025).

Praveen, V. et al. Harnessing trichoderma asperellum: Tri-Trophic interactions for enhanced black gram growth and root rot resilience. J. Basic Microbiol. e2400569 https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400569 (2024).

Vafa, Z. N., Sohrabi, Y., Heidari, G., Rizwan, M. & Sayyed, R. Z. Wheat growth and yield response are regulated by mycorrhizae application and supplemental irrigation. Chemosphere 364, 143068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143068 (2024).

Ferioun, M. et al. Applying microbial biostimulants and drought-tolerant genotypes to enhance barley growth and yield under drought stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1494987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1494987 (2025).

Bright, J. P. et al. Biofilmed-PGPR: A next-generation bioinoculant for plant growth promotion in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under changing climate. Rice Science. (2025). (2025). (32) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsci.2024.08.008

Chaithra, M. et al. Fungal Bio-stimulants: Cutting-Edge bioinoculants for sustainable agriculture. In Plant Microbiome and Biological Control. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection Vol. 20 (eds Mathur, P., Roy, S. et al.) 289–307 (Springer, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75845-4_13.

Aktar, S. N. et al. Beneficial microbes in plant Health, immunity and resistance. In Plant Microbiome and Biological Control. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection Vol. 20 (eds Mathur, P., Roy, S. et al.) 1–17 (Springer, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75845-4_1.

Najafi, S. et al. R.Z., and Biofertilizer application enhances drought stress tolerance and alters the antioxidant enzymes in medicinal pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo convar. pepo var. Styriaca). Horticulturae, 7(12), 588 https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/7/12/588/htm (2021).

Bhat, B. A. et al. T.U.H. The role of plant-associated rhizobacteria in plant growth, biocontrol, and abiotic stress management. J. Appl. Microbiol. 133 (5), 2717–2741 (2021).

Havaux, M. & Kloppstech, K. The protective functions of carotenoid and flavonoid pigments against excess visible radiation at chilling temperature investigated in Arabidopsis Npq and Tt mutants. Planta 213, 953–966 (2001).

Barrs, H. D. & Weatherley, P. E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 15 (3), 413–428 (1962).

Prieto, P., Pineda, M. & Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 269 (2), 337–341 (1999).

Honma, M. & Shimomura, T. Metabolism of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid. Agric. Biol. Chem. 42 (10), 1825–1831. https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1978.10863261 (1978).

Marklund, S. & Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 47 (3), 469–474 (1974).

Beers, R. F. & Sizer, I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195 (1), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50881-X (1952).

Salbitani, G., Bottone, C. & Carfagna, S. Determination of reduced and total glutathione content in extremophilic microalga Galdieria phlegrea. Bio-protocol 7 (13), e2372–e2372. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.2372 (2017).

Zhang, X. Z. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation and SOD, POD, and CAT activities in biological systems. Res. Methodol. Crop Physiol., 208–211, (1992).

Dos Santos, T. B., Ribas, A. F., de Souza, S. G. H., Budzinski, I. G. F. & Domingues, D. S. Physiological responses to drought, salinity, and heat stress in plants: a review. Stresses 2 (1), 113–135 (2022).

Ahmed, M., Tóth, Z. & Decsi, K. The impact of salinity on crop yields and the confrontational behavior of transcriptional Regulators, Nanoparticles, and antioxidant defensive mechanisms under stressful conditions: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (5), 2654 (2024).

Kapadia, C. et al. Evaluation of plant growth-promoting and salinity ameliorating potential of halophilic bacteria isolated from saline soil. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 946217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.946217 (2022).

Sagar, A. et al. ACC deaminase and antioxidant enzymes producing halophilic Enterobacter sp. PR14 promotes the growth of rice and millets under salinity stress. Physiol. Mol. Biology Plants. 26, 1847–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00852-9 (2020).

Khumairah, F. H. et al. Halotolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria isolated from saline soil improve nitrogen fixation and alleviate salt stress in rice plants. Front. Microbiol. 13, 905210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.905210 (2022). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/

Hashem, A., Tabassum, B. & Abd_Allah, E. F. Bacillus subtilis: A plant-growth-promoting rhizobacterium that also impacts biotic stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 26 (6), 1291–1297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.05.004 (2019).

Douka, D., Spantidos, T. N., Tsalgatidou, P. C., Katinakis, P. & Venieraki, A. Whole-Genome profiling of endophytic strain B.L.Ns.14 from Nigella sativa reveals potential for agricultural bioenhancement. Microorganisms 16 (12), 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122604 (2024).

Darakeh, S. A. S. S., Weisany, W., Tahir, N. A. & Schenk, P. M. Physiological and biochemical responses of black Cumin to vermicompost and plant biostimulants: arbuscular mycorrhizal and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Industrial Crops Products, 188(A),2022, 115557, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115557 (2022).

Saddiq, M. S. et al. Effect of salinity stress on physiological changes in winter and spring wheat. Agronomy 11 (6), 1193 (2021).

Jabborova, D. P., Narimanov, A. A., Enakiev, Y. I. & Davranov, K. D. Effect of Bacillus subtilis 1 strain on the growth and development of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under saline conditions. Bulgarian J. Agricultural Sci. 26 (4), 744–747 (2020).

Jabborova, D. et al. Co-inoculation of rhizobacteria promotes growth, yield, and nutrient contents in soybean and improves soil enzymes and nutrients under drought conditions. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 22081. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01337-9 (2021).

Jabbarova, D. et al. Dual inoculation of plant growth-promoting Bacillus endophyticus and Funneliformis Mosseae improves plant growth and soil properties in ginger. ACS Omega. 7 (39), 34779–34788 (2021).

Ali, B. et al. PGPR-mediated salt tolerance in maize by modulating plant physiology, antioxidant defense, compatible solutes accumulation, and biosurfactant-producing genes. Plants 11 (3), 345 (2022).

Hoseini, A. et al. Efficacy of biological agents and filler seed coating in improving drought stress in Anise. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 955512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.955512 (2022).

Azeem, M. et al. Salinity stress resilience in sorghum bicolor through Pseudomonas-Mediated modulation of Growth, antioxidant System, and Eco-Physiological adaptations. ACS Omega. 10 (1), 940–954 (2025).

Azeem, M. A. et al. Halotolerant Bacillus Aryabhattai strain PM34 mitigates salinity stress and enhances the physiology and growth of maize. J. Plant Growth Regul. 6, 1–9 (2022).

Ramzan, M. et al. Potential of Kaempferol and caffeic acid to mitigate salinity stress and improving potato growth. Sci. Rep. 17 (1), 21657 (2024).

Ramadan, M. E. Alleviation of irrigation water salinity impact on the growth and yield of sweet potatoes by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 65 (4), 669–677 (2024).

Shahid, M., Altaf, M., Ali, S. & Tyagi, A. Isolation and assessment of the beneficial effect of exopolysaccharide-producing PGPR in Triticum aestivum (L.) plants grown under NaCl and Cd-stressed conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1, 215, 108973 (2024).

Elbagory, M. et al. Feasibility of Nano-Urea and PGPR on salt stress amelioration in Reshmi Amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor): stress markers and enzymatic response. Horticulturae 5 (3), 280 (2025).

Kusale, S. P. et al. Production of plant beneficial and antioxidant metabolites by Klebsiella variicola under salinity stress. Molecules 26 (7), 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071894 (2021).

Kusale, S. P. et al. Inoculation of Klebsiella variicola alleviated salt stress and improved growth and nutrients in wheat and maize. Agronomy, 11(5), 927 https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/11/5/927/htm (2021).

Enayatfard, L., Mohebbati, R., Niazmand, S., Hosseini, M. & Shafei, M. N. The standardized extract of Nigella sativa and its major ingredient, thymoquinone, ameliorates angiotensin II-induced hypertension in rats. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 30 (1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbcpp-2018-007 (2018).

Soni, S. et al. Variability of durum wheat genotypes in terms of physio-biochemical traits against salinity stress. Cereal Res. Commun. 49, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42976-020-00087-0 (2021).

Jabborova, D. et al. Mineral fertilizers improves the quality of turmeric and soil. Sustainability 13 (16), 9437 (2021).

Jabborova, D. et al. Co-inoculation of Biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizae for growth promotion and nutrient fortification in soybean under drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 947547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.947547 (2022).

Tanveer, S. et al. Interactive effects of Pseudomonas Putida and Salicylic acid for mitigating drought tolerance in Canola (Brassica Napus L). Heliyon 9 (3), e14193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14193 (2023).

Rafique, N. et al. Interactive effects of melatonin and Salicylic acid on brassica Napus under drought conditions. Plant. Soil. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-05942-7 (2023).

Mohanavelu, A., Naganna, S. R. & Al-Ansari, N. Irrigation-induced salinity and sodicity hazards on soil and groundwater: an overview of its causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Agriculture 11 (10), 983 (2021).

Kapadia, C. et al. A.T.K. Halotolerant microbial consortia for sustainable mitigation of salinity stress, growth promotion, and mineral uptake in tomato plants and soil nutrient enrichment. Sustainability, 13(15), 8369 https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/15/8369 (2021).

Sagar, A. et al. ACC deaminase and antioxidant enzymes producing halophilic Enterobacter sp. PR14 promotes the growth of rice and millets under salinity stress. Physiol. Mol. Biology Plants. 26, 1847–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00852-9 (2020).

Gowtham, H. G. et al. Insight into recent progress and perspectives in the improvement of antioxidant machinery upon PGPR augmentation in plants under drought stress: a review. Antioxidants 11 (9), 1763 (2020).

Nasab, B. & Sayyed, R. Z. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and salinity stress: A journey into the soil. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management. Microorganisms for Sustainability Vol. 12 (eds Sayyed, R. et al.) 21–34 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6536-2_2.

Shahid, M. et al. Bacterial ACC deaminase: insights into enzymology, biochemistry, genetics, and potential role in amelioration of environmental stress in crop plants. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1132770 (2023).

Sagar, A., Yadav, S. S., Sayyed, R. Z., Sharma, S. & Ramteke, P. W. Bacillus subtilis: a multifarious plant growth promoter, biocontrol agent, and bioalleviator of abiotic stress. In Bacilli in Agrobiotechnology: Plant Stress Tolerance, Bioremediation, and Bioprospecting 561–580 (Springer, 2022).

Fatima, T. and Naveen Kumar Arora. Pseudomonas entomophila PE3 and its exopolysaccharides as biostimulants for enhancing growth, yield, and tolerance responses of sunflower under saline conditions. Microbiol. Res. 244 : 126671 (2021). (2021).

Moradzadeh, S. et al. H.A., and Biochemical fertilizer improves the oil yield, fatty acid compositions, and macronutrient contents in Nigella sativa L. Horticulturae, 7(10), 345. https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/7/10/345 (2021).

Devkota, K. P., Devkota, M., Rezaei, M. & Oosterbaan, R. Managing salinity for sustainable agricultural production in salt-affected soils of irrigated drylands. Agric. Syst. 198, 103390 (2022).

Sridhar, D. et al. Halophilic rhizobacteria promote growth, physiology, and salinity tolerance in Sesamum indicum L. grown under salt stress. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1590854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1590854 (2025).

Jabborova, D. et al. Enhancing growth and physiological traits in alfalfa by alleviating salt stress through biochar, hydrogel, and biofertilizer application. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1560762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1560762 (2025).

Jabborova, D. et al. Assessing the synergistic effects of biochar, hydrogel, and biofertilizer on growth and physiological traits of wheat in saline environments. Functional Plant. Biology 52, FP24277 https://doi.org/10.1071/FP24277 (2025).

Simarmataa, T. et al. Integrating metabolomics and transcriptomics for SynCom-Driven rhizomicrobiome engineering in Salinity-Stressed rice. J. Plant. Interact. 20 (1), 2567358. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2025.2567358 (2025).

Khairnar, M. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of Sinorhizobium meliloti isolates associated with Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum Linn.) from diverse agroclimatic regions of India. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 12, 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-025-00811-0 (2025).

Tariq, A. et al. Endophytes: key role players for sustainable agriculture: mechanisms, omics insights and future prospects. Plant. Growth Regul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-025-01370-y (2025).

Sridhar, D. et al. The soil Microbiome enhances Sesame growth and oil composition, and soil nutrients under saline conditions. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15589-2 (2025).

Pradhan, N. et al. A review on microbe–mineral transformations and their impact on plant growth. Front. Microbiol. 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1549022 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-358), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the Ministry of Innovational Development of the Republic of Uzbekistan vide grant Number FL-8323102111-R1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, and project administration; DJ., Investigation, and Methodology; MN, NB, and ZJ., Writing-Original draft; DJ and RS. Writing- review and editing, formal analysis KP, JB, APG, NYR, and R.S. Fund acquisition; KP.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study did not include any procedures on humans or animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jabborova, D., Nurmatova, M., Bisht, N. et al. Multipotential rhizobacteria simultaneously mitigate salinity stress and improve growth and physiological traits in black cumin (Nigella sativa L.). Sci Rep 15, 42807 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26925-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26925-x