Abstract

As a crucial root vegetable, the phenomenon of bolting and flowering presents a significant challenge to the commercial value of carrot. However, the genetic mechanism of carrot bolting remains to be fully elucidated. In this study, we conducted a two-year cultivation experiment with a population of 240 carrots to examine traits associated with bolting. We conducted whole-genome sequencing on these carrots and subsequently performed population structure analysis, as well as genome-wide association studies (GWAS). A total of nine single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci were identified across diverse environmental conditions that exhibited significant associations with bolting speed and other traits. Furthermore, within 93 candidate genes identified, the RING-domain zinc-finger protein LOC108205243 was determined to play a significant role in the regulation of bolting traits. The SNPs and candidate genes identified in this research may serve as molecular markers for bolting traits, thereby offering essential resources for genetic engineering breeding efforts aimed at managing bolting in carrots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carrots are one of the most popular vegetables in the world and are rich in nutrients in their roots1. Bolting is a natural phenomenon in the process of flower bud differentiation and flowering in vegetables2. As a biennial plant, carrot mainly experiences a nutritive growth phase in the first year. After a period of vernalization at low temperature, carrot begins to bolt under suitable environmental conditions. Bolting and flowering represent pivotal stages in the seed production and breeding of carrot3. Environmental factors, such as low temperature and long days can induce flower bud differentiation and promote bolting and flowering4,5. However, during the planting process, early bolting causes lignification in the fleshy root of the carrot, resulting in reductions in production and quality and a loss of commercial value6. Therefore, the systematic identification and screening of core germplasm resources with bolting-related traits for bolting tolerance are critical steps for carrot breeding.

Bolting is one of the most important agronomic traits affecting the quality and yield of crops, and it determines their growth season and cultivation area7. The xylem of carrot lignifies immediately after vernalization, a transformation that significantly impacts palatability and leads to a reduction in commercial value8,9. Bolting is regulated by multiple regulatory pathways as well as environmental conditions4. These include the photoperiod, vernalization, gibberellic acid, autonomy, age, and temperature pathways10. Flowering time is influenced by both endogenous and exogenous signaling, via joint control mechanisms11. In summary, carrot bolting represents a quantitative genetic trait influenced by intricate environmental conditions and internal signaling pathways. Consequently, the identification of critical genes and molecular markers underlying this phenomenon is an essential prerequisite for the development and preservation of high-quality, commercially viable anti-bolting cultivars.

Current research on the molecular mechanisms of bolting has primarily focused on model plants and crops. Most of these genes from different species occur in the main flowering pathway, including flowering-time genes (FTGs)12 and the flowering integration genes LFY (Leafy)11,13, TFL1 (Terminal Flower 1)14, SOC1 (Suppressor of overexpression of constans), and FT (Flowering Locus)15. Studies on carrot have revealed the effects of low-temperature vernalization and the photoperiod pathway in regulating bolting traits16, as well as the expression pattern and underlying mechanisms of FLC (Flowering Locus C)17, CO (Constans)18, GI (Gigantea), and VIN3 (Vernalization insensitive 3)19. RNA-seq analysis of flowering pathways in eastern and western carrot varieties showed that differentially expressed genes in the photoperiod and vernalization pathways were upregulated in western varieties, while autonomous pathways (flowering site D (FLD), luminescence dependence (LD), flowering site K (FLK), and phospholipid binding protein (PEBP)) were significantly enriched in eastern varieties20. Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying bolting in carrots remain largely unexplored. Therefore, exploring the molecular mechanism and inheritance patterns associated with carrot bolting provides valuable information for future molecular breeding to select appropriate genes for bolting-resistance traits and improving bolting resistance without affecting plant yields and quality21.

Population genomics integrates the research fields of population genetics and genomics. It provides a more thorough and systematic understanding of variation patterns, evolutionary mechanisms, and the relationships between genes and phenotypes within the genome by analyzing the genomic data of large numbers of individuals22. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) involve sequencing natural populations, and this represents is a system biology method used to detect valuable single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variations23. With the rapid development of molecular marker and sequencing technologies, GWAS has been widely applied to analyze the genetic mechanisms underlying plant phenotypic trait variations, such as a GWAS of grain color and tannin contents in Chinese sorghum24. Further, GWASs have been widely applied to rice, corn, wheat, soybean, cotton, and other types of crops to study their agronomic traits25. GWASs can be used to uncover differences in phenotypic changes at the genetic level, identifying SNP loci and candidate genes that contribute to traits that can improve breeding efficiency.

In this study, a total of 240 diverse carrots were employed to systematically assess phenotypic variation and estimate genetic parameters for traits including bolting time, bolting rate, and bolting height. GWAS were conducted using whole-genome resequencing data to identify SNPs significantly correlated with bolting-related traits, completing the identification of candidate genes. Additionally, public transcriptomic datasets and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses were utilized to validate the expression profiles of key genes implicated in bolting. The findings aim to assist the research on molecular mechanism of carrot bolting and the molecular marker-assisted breeding to enrich anti-bolting properties in carrots.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and phenotyping

In total, 240 carrots from the Center of the Vegetable Technical Service (Xining, China) were used in this study (Supplementary Table S1). The taproots of these carrots exhibited a variety of root tip shapes (pointed, blunt pointed, and circular) and fleshy root colors (white, yellow, orange, orange red, red, magenta, and purple).

From 2021 to 2022, 240 carrots were grown in four different locations in Qinghai province, as follows: April 2021, Tianjiazhai Town, Huangzhong District [N36°27′40″, E101°47′46″]; June 2021, Biopark District [N36°41′34″, E101°45′19″]; April 2022, Lanlongkou Town, Huangzhong District [N36°46′24″, E101°29′34″]; June 2022, Xingquan Town, Huangyuan County [N36°43′34″, E101°12′58″]. All experiments were conducted using a randomized block design. Strip planting was adopted as the sowing method, and the land preparation method was ridge covering with plastic film. The ridge height was 20 cm, the ridge width was 80 cm, and the plant spacing was 5 cm; each ridge was planted in four 1.5 m-long rows. The seedlings were covered with non-woven fabric for moisture preservation during the emergence period, and the non-woven fabric was removed after the seedlings had completely formed. The fields were irrigated and fertilized according to standard local cultivation practices.

In four experimental areas, five lines of each variety were randomly selected for investigation. According to the description specification and data standard of carrot germplasm resources26, the seven agronomic traits such as Root tip phenotype (RTP), Central column phenotype (CCP), Epidermal traits (ET), Fleshy root color (FRC), Root thick (RT), Central column thick (CCT), Single root weight (SRW) were measured. Single root weight (SRW) was weighed using an electronic balance. Bolting time (BT) refers to the number of days from the date of planting to the start of bolting. Bolting rate (BR) is the ratio of the number of bolting plants to the total number of plants. Bolt height (BH) refers to the distance from the base of bolting to the top of the flower stem. Bolting speed (BS) is the ratio of bolt height to bolt time.

Genome resequencing

Genomic DNA extraction from young leaves of 240 carrots was performed using a new plant genomic DNA kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Genome sequencing was performed by Wuhan Maitewei Biotechnology Co. Ltd. DNA sequencing libraries were generated using the Illumina HiSeq PE150 sequencing platform. The experiment generated a total of 1.11 Terabytes (Tb) of raw data. We strictly filter the raw sequencing data using the following methods: (1) Remove read pairs containing adapter sequences; (2) Remove paired reads with N content exceeding 10% of the length ratio of the single ended sequencing read; (3) Remove paired reads containing low-quality (quality value Q ≤ 5) alkaline bases exceeding 50% of the length of the single ended sequencing read. After filtering, we obtained a high-quality cleaning sequence of 1.10 Tb.

SNP calling and population genetic analysis

We compared and located the clean data with the carrot reference genome (Daucus carota v2.0) using the BWA software (version 0.6, parameter: mem -t 4 -k 32 -M)27. The comparison results were deduplicated by SAMTOOLS28 (version 1.17, parameter: rmdup), and the size of the genome excluding the gap region was 386,795,034 bp. The average alignment rate of the population sample was 94.69%, and the average sequencing depth of the genome (excluding the gap region) was 9.89X (only considering reads with alignment quality greater than 0). The average coverage was 87.74% (covering at least one base) (Supplementary Table S4). Population SNPs were detected using SAMTOOLS software (version 1.17)28. To minimize the impact of false positives as much as possible, the SNPs were filtered with a single sample sequencing depth > 4×, a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.05, and a missing rate < 0.2 to obtain high-quality SNPs. The SNP detection results were annotated using ANNOVAR (Version: 2013-06-21)29.

TreeBeST software (version 1.9.2, https://treesoft.sourceforge.net/treebest.shtml) was used to generate a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with the Kimura 2-parameter model, 1000 bootstrap replicates. The software MEGA (version 6.0, http://www.megasoftware.net/) was used for visualizing the phylogenetic trees30. GCTA software (version 1.24.2, http://cnsgenomic.comsoftware/gcta/) was used to perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to evaluate genetic structure31. The population genetics structure was examined using an expectation maximization algorithm as implemented in the program ADMIXTURE (version 1.23)32. PopLDdecay software (version 3.40) was used to assess the linkage disequilibrium (LD) coefficient (r2) between pairwise SNPs across the carrot genome33.

GWAS analysis and candidate gene identification

In the process of GWAS, individual kinship and population stratification represent primary sources of false positive associations. The Mixed Linear Model (MLM) approach addresses control of false positives by simultaneously accounting for population structure and individual kinship, thereby reducing computational burden while maintaining analytical accuracy. Utilizing SNP data derived from resequencing, we performed trait association analyses employing the genome-wide efficient mixed model association program (GEMMA, version 0.98.1, parameter: -bfile -p -c -k -lmm 1 -miss $miss -maf $maf) alongside the Mixed Linear Model34. In this model, population genetic structure was incorporated as a fixed effect, whereas individual kinship was modeled as a random effect to correct for their respective influences. Candidate SNPs were identified based on a significance threshold (P-value < 0.05/N). The significance threshold was estimated as − log10(P) = 5.0. The genomic regions within the LD block of the peak SNPs were selected to identify candidate genes. Visualization of the association results was conducted using Manhattan and quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots generated via the qqman package in the R software35. Using lme4 software, a mixed linear model was used to calculate the BLUE values of carrot bolting traits36.

Transcriptome and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

To investigate the expression patterns of LOC108205243 in different carrot tissues, the RNA-seq data from a previous study were downloaded from the SRA database of NCBI (Accession: SRP062159)37. RNA-seq reads of all samples were mapped to the carrot genome by the Hisat2 tool of the TBtools software38. Then, the sequencing data was converted into gene expression matrices using the TBtools software. Subsequently, the TPM expression matrix was normalized using the formula log2 (TPM + 1) in R software. The expression matrix was visualized using Chiplot (https://www.chiplot.online/).

To investigate the role of candidate genes in the carrot bolting process, we selected three carrots (B228, B227, and 21DL-10) that exhibited high, medium, and low bolting speeds, respectively, for subsequent experiments. Leaf RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed using OminiPlant RNA Kit (DNase I) from Cwbio (code: CW2598S) and MonScript™ RTIII All-in-One Mix with dsDNase kit from Monad (code: MR05101), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The real-time PCR reaction was performed on the ABI7500 real-time PCR system. QIAGEN 2x QuantiNova SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (code: 208054) was used with gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S5). The qPCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95℃ for 30 s for pre-incubation, followed by 40 cycles of 95 ℃ for 10 s, 60 ℃ for 30 s and 72 ℃ for 30 s. The tubulin was used as an internal control for normalization. The relative transcription levels of the LOC108205243 gene relative to tubulin were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt methods, with 3 replicates per sample39.

Sequence analysis and of interacting proteins prediction

The sequences of the candidate genes were downloaded from the NCBI database (Daucus carota v2.0), and ClustalX (version 2.1)40 and MEGA (version 7.0)41 were used for multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis. Related sequences from Arabidopsis were obtained from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). The protein interaction network of LOC108205243 and used the STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl) to predict the interacting proteins42.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 17.0) was used to calculate the mean (x̄), maximum (max), minimum (min), and standard deviation (σ) of each trait43. The coefficient of variation (CV = (σ / x̄) × 100%) was computed in Excel. Based on the mean and standard deviation of the carrot germplasm data, the bolting-related traits were divided into 10 classes: class 1, Xi < (x̄ – 2σ); class 10, Xi ≥ (x̄ + 2σ); each class interval was 0.5σ. The diversity index (H') was then calculated as: H'= –Σ pi ln pi. Where pi is the percentage of total resources within level i of a certain trait. This study conducted correlation analysis on the data using SPSS software44. Specifically, the Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated, and a two-tailed significance test was conducted. And the data was subjected to the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test using SPSS software. The means and standard errors were calculated, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical distribution graph of the phenotype values and correlation heatmap were plotted using Origin software.

Results

Genetic variation

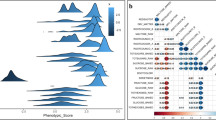

In total, 240 carrots were selected for whole-genome resequencing analysis, and premature bolting during carrot cultivation was investigated. Our analyses identified three major quantitative traits, and the four bolting-related traits. We conducted an analysis of the frequency distribution for seven agronomic traits across a sample of 240 carrot specimens (Fig. 1). Those traits displayed a unimodal continuous distribution, with traits other than bolting rate approaching a normal distribution. These results align with the genetic properties associated with quantitative traits governed by polygenic inheritance. The results showed that the range of variation for seven indicators, among different carrots, was 22.78 ~ 137.86%, with a range of 52.60 ~ 533.83 g for the single root weight and a coefficient of variation of 49.94%. The bolt height exhibited a range of variation of 0–148.50 cm and a coefficient of variation of 71.59%. The maximum coefficient of variation for the bolting rate was 137.86%. This indicates that there was a significant difference in the single-root weight and bolt height among the different carrots. There was also a significant difference in bolt tolerance among the different carrots, indicating significant differences in the quality of the succulent roots. The diversity index of the seven traits showed significant differences, ranging from 1.38 to 2.09, indicating that the genetic diversity of the seven traits in the 240 carrots was relatively rich. The order of the diversity indices of the four bolting traits was as follows: bolting speed (1.75) > bolting height (1.59) > bolting rate (1.54) > bolting time (1.38). The diversity indices of the three fleshy root traits were ranked as follows: center column diameter (2.09) > root diameter (1.98) > single root weight (1.71). From this, it can be seen that the genetic diversity index associated with bolting speed was the highest among the bolting traits, and the genetic diversity index of the central column diameter was highest among the fleshy root traits.

The bolting conditions of the different varieties in the field were diverse (Fig. 2A). Bolting caused the carrots to lose their commercial value (Fig. 2B). A correlation analysis was conducted on the four bolting traits and seven agronomic traits of the carrots, as shown in Fig. 2C. The results showed a highly significant positive correlation between the bolting time (BT) and bolting rate (BR), bolt height (BH), and bolting speed (BS), with correlation coefficients of 0.39, 0.40, and 0.33, respectively. The correlation coefficients between the bolting rate (BR) and bolt height (BH) or bolting speed (BS) were 0.79 and 0.85, respectively. Compared with other bolting traits, the coefficient between the bolting height (BH) and bolting speed (BS) was the highest, at 0.98. Furthermore, the result revealed a strong positive association between bolting rate (BR) and both the central column phenotype (CCP) and the epidermal traits (ET) of fleshy roots. The fleshy root color (FRC) exhibited a significant negative correlation with root thick (RT) and central column thick (CCT). Additionally, a marked positive correlation was observed between the central column phenotype (CCP) and both bolting speed (BS) and bolt height (BH). An obvious correlation was also identified between central column phenotype (CCP) and single root weight (SRW). Agronomic traits that demonstrate significant correlations with bolting characteristics may be effectively utilized for the comprehensive selection of carrot germplasm exhibiting bolting tolerance.

Cluster analysis according to bolting-related traits

Cluster analysis of the four bolting correlations among the 240 carrots, divided into four major groups, was conducted using the Ward method, as shown in Fig. 3A. Based on the clustering results, a statistical analysis of the bolting correlations among the four groups was conducted (Supplementary Table S2). The first category included 71 carrots with a 2-year bolting rate of 0, belonging to an extremely tolerant to bolting genotype, and the calculated Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) values were all 77.27. The second category included 122 carrots, and their average bolting rate, bolting height, bolting speed, and BLUE values were 105.09, which were higher than those of the other three categories of carrots. This indicates that this type of material has a short bolting time, high bolting rate, and fast bolting speed and belongs to the category of easy bolting carrots. There were 30 carrots in the third category, with a bolting rate that was lower than the average for all materials belonging to bolting tolerance materials. There were 17 carrots in the fourth category, which had the longest bolting time but a lower bolting rate, belonging to medium bolting tolerance carrots.

Population structure and linkage disequilibrium (LD) of 240 carrots. (A) Clustering heatmap of bolting time, bolting rate, bolt height, and bolting speed from 240 carrots. (B) SNP detection and annotations statistics in 240 carrots by resequencing. (C) PCA of all radish genotypes. The principal components (PC1, PC2 and PC3) were used to visualize the relationships among individuals and groups. Each point represents an independent carrot genotype. (D) The LD decay plot of 240 carrots by r2.

Population structure, and linkage disequilibrium (LD) analyses formatting of mathematical components

After sequencing the 240 carrots, we identified 50,596,401 SNPs, and after filtering, 19,056,107 high-quality SNPs remained. The filtered SNP sites were annotated using ANNOVAR software, and the annotation results are shown for 1,222,620 SNPs, which had been annotated SNPs (Fig. 3B). The SNPs were unevenly distributed across the nine chromosomes. The ADMIXTURE software was employed to analyze the population structure of this natural population. The analysis showed that the cross-validation (CV) error reached its minimum at K = 4, suggesting that the optimal number of subgroups is four (Supplementary Fig. S1). PCA was performed on 240 carrot SNPs, revealing that varieties from diverse countries and regions were intermingled without distinct geographical clustering (Fig. 3C). Additionally, a distance matrix was computed using TreeBest, which classified the 240 carrot accessions into four primary groups comprising 102, 55, 49, and 34 varieties, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). These findings collectively corroborate the reliability of the inferred population structure. Then, we estimated the LD of 240 carrots using 19,056,107 high-quality SNPs. The r² values were calculated by PopLDdecay, and LD decay plots were plotted. Employing an r² threshold of 0.1, the corresponding physical distance at which LD decayed was determined to be 35 kb (Fig. 3D). The smooth decay curve of LD indicates that SNPs are evenly distributed and have sufficient density on the genome. This result is also consistent with the slow LD decay caused by the presence of a large number of inbred lines (185/240, Supplementary Table S1) in the material.

Association mapping and screening of SNPs

Regarding the correlation between bolting-related marker-trait associations analysis among the 240 carrots, in total, nine significantly associated SNPs were detected at the applied significance threshold (− log10 P > 5) for the association analysis of the bolting speed in the year 2022 (Table 1). This implies that these parameters are closely related to the bolting speed. Notably, one leading SNP (33,254,067) was observed on chromosome (Chr) 1, which was selected for an association analysis the bolting speed and bolt height (Fig. 4A, B). At the same time, the BLUE value was also associated with this significant site in the GWAS (Fig. 4C). The related to bolting speed in the genome coordinate 33,254,067 becoming an interesting candidate SNP. Additionally, there were 36 and 47 significantly associated SNPs were detected for the association analysis of the BT (bolting time) and BR (bolting rate) in the year 2022, distributed on all 9 chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B).

Based on the LD level, 93 total candidate genes were identified in the space defined by the ± 100 kb regions on either side of the nine peak SNPs (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, based on an analysis of the selected SNP with a peak position of 33,254,067 on chromosome 1, which was associated with 12 candidate genes, nine of the genes had annotations. These included LOC108193703, encoding an annotated mitochondrial zinc maintenance protein, and LOC108195189, encoding a pectinesterase inhibitor. Remarkably, the functional annotation of LOC108205243 indicated that it is an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, suggesting that it might be a potential candidate gene responsible for carrot bolting.

GWAS analysis for bolting speed in carrot. (A) Manhattan plots (left) and quantile-quantile plots (right) depicting results of the GWAS for bolting speed in 2022 year. (B) Manhattan plots (left) and quantile-quantile plots (right) depicting results of the GWAS for bolting height in 2022 year. (C) Manhattan plots (left) and quantile-quantile plots (right) depicting results of the GWAS for BLUE. The x-axis depicts the physical location of SNPs across the 9 chromosomes of carrot, and the y-axis depicts the − log10 (P-value)

Identification of the candidate gene

The LD of LOC108205243 was shown in Fig. 5A. LOC108205243 was located 1360 bp upstream of the peak SNP (33304067). To further investigate the candidate gene LOC108205243, in terms of the regulation of bolting traits, protein structure analysis was performed (Supplementary Fig. S4), based on a typical ring domain structure. Protein interactions were predicted to explore the function of LOC108205243 proteins in the carrot network (Supplementary Fig. S5). The results indicate that LOC108205243 proteins may be co-expressed with transcription factors LONESOME HIGHWAY (LHW, DCAR_012241, DCAR_018203), CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE INHIBITOR 7 (CDKi7, DCAR_022035, DCAR_025727), and other proteins. We further analyzed the correlation between the orthologs of the LOC108205243 proteins (Fig. 5B). Our results showed that LOC108205243 amino acid sequences in carrot share high homology with the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RFI2 (Red and Far-Red insensitive) in different species. AtRFI2 negatively regulates CO and FT to participate in the regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis45. We thus speculate that LOC108205243 is related to the bolting and flowering of carrots.

Furthermore, we selected three carrot varieties, B228, B227, and 21DL-10, which exhibit high, medium, and low bolting speeds, respectively. Subsequently, we measured their bolting heights (Fig. 5C). The transcript abundances of LOC108205243 in the three carrot genotypes were measured using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis (Fig. 5D). The gene LOC108205243 exhibits its highest expression level in the 21DL-10 genotype, whereas it shows the lowest expression level in the B228 genotype (Fig. 5D). This observation shows a discordant relationship between gene expression and phenotypic traits. Such a pattern implies that the regulation of bolting characteristics by LOC108205243 is unlikely to follow a straightforward dose-dependent mechanism. Instead, it may involve complex regulatory processes including post-transcriptional inhibition, protein modifications, upstream negative feedback loops, and the buffering effects arising from interactions with other genes. The exact mode of action of the LOC108205243 gene still needs to be further validated through gene editing and other methods.

Characteristic analysis of LOC108205243 gene. (A) Regional Manhattan plots and linkage distribution (LD) heatmap of LOC108205243. (B) Multiple alignments of LOC108205243 (XP_0172308) and RFI2 proteins family with identified in different species. (C) Bolting speed and bolting height in different genotypes of carrot. (D) The relative expression level of LOC108205243 gene in 3 genotypes of carrot.

Expression patterns of the candidate gene

In order to investigate the role of LOC108205243 in regulating carrot bolting-related traits, expression patterns of the LOC108205243 gene in different tissue parts and developmental stages of carrots were analyzed using public RNA-seq data from the NCBI SRA database (Fig. 6). LOC108205243 was highly expressed in leaves stage 2 and leaves stage 3.

Expression of LOC108205243 gene in different carrot tissues. The color bars in the heatmap indicate the TPM values of log-transformed LOC108205243 gene. Sd1, Bud and Cal represented germinating seeds, 0.5 mm buds and callus, respectively. Br1 and Br2 represented the bracts of unopened flower and opened flower. Fl1 and Fl2 represented unopened whole flower and opened whole flower. Lf1, Lf2, Lf3 and Lfe represented leaves stage 1 (0.5–1 cm bud), leaves stage 2 (2–2.5 cm, unexpanded), leaves stage 3 (7–8 cm, unexpanded) and etiolated leaves, respectively. Pet, Hyp, Phl, Xyl, Rft, Pts, and Rts represented 10 cm petioles (from leaves stage3), hypocotyls, phloem, xylem, fibrous roots, stressed leaves (at reversible wilting point) and stressed roots, respectively. Ls1 and Ls2 represented stressed leaves of 2–2.5 cm and 7–8 cm at reversible wilting point.

Discussion

It is necessary to consider the biodiversity of carrots as a genetic source of useful and indispensable components for genetic diversity assessments of carrot breeding accessions46. In this study, a total of 240 carrots were collected, and the phenotypic analysis revealed an approximately normal distribution of their trait frequencies (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the analysis identified significant differences in genetic diversity and evolutionary directions among the samples. Strong characteristic associations between the root length, root diameter, and root weight and marketable yield have been suggested as a selection criterion for higher yields47. Bolting and flowering are the most important stages of the life cycle of a plant. Bolting significantly affects the quality and merchantability of carrot roots. Likewise, the bolting speed, height, rate, and time all exhibited the highest heritability and moderate genetic advances, and these were suggested to be the selection criteria for bolting (Fig. 2C). Bolting is closely related to plant reproduction, but the molecular mechanisms underlying plant flowering are complex48,49. A core collection of studies and those related to development have been applied to tea (Camellia sinensis)50, cowpeas51, alpine plums52, and walnuts53. Further, core germplasm resources are applied to relatively small populations with high genetic diversity54. Based on a correlation analysis of different bolting-related traits, we constructed a core collection. We identified 71 parts comprising markedly bolting-resistant carrots, 30 parts comprising resistant carrots, 122 parts comprising easy bolting carrots, and 17 parts comprising relatively easy bolting carrots (Fig. 3A). Core germplasm resources are invaluable fundamental resources for improving varieties55. The genetic diversity, population structure, and core collection elucidated based on bolting in this study will facilitate further genetic studies, germplasm protection, and carrot breeding.

Compared with traditional research based on classical QTL mapping, GWAS possesses the capability to identify genetic variations throughout the entire genome. It can reveal the genetic structure of quantitative traits more comprehensively. A population with abundant phenotypic and genetic variations was previously subjected to GWAS analysis56. Moreover, a GWAS and selective sweep research have revealed the origin of high-carotenoid orange carrots57. In previous studies, the root transcriptomes of widely differing cultivated and wild carrots were sequenced and introduced to optimize the identification of 11,369 SNPs58. This study used the GWAS method to conduct a correlation analysis of bolting and identified 1,222,620 total SNPs that had been annotated. Using the r² threshold of 0.1 and 0.2, we estimated that the physical distance corresponding to linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay is approximately 35 kb and 4.63 kb, respectively (Fig. 3D). A review of existing literature on LD in carrots revealed a limited number of studies addressing whole-genome LD decay. Notably, Clotault et al. (2010)59 and Soufflet-Freslon et al. (2013)60 reported no detectable LD decay within candidate gene fragments ranging from 0.7 to 1.0 kb and within a 4,234 bp sequence of the CRTISO gene, respectively. Wild carrots demonstrated a very rapid LD decay within the genome range of approximately 100 bp (r2 = 0.2) and 1 kb (r2 = 0.1), while domesticated carrots demonstrated a rapid LD decay between approximately 400 bp (r2 = 0.2) and 13 kb (r2 = 0.1)6. A comparable short-range LD decay estimate is provided by Brainard et al. (2022)61, who analyzed 146,816 SNPs and observed an LD decay distance of approximately 19.7 kb at r² = 0.1. This value is roughly 40% shorter than the 35 kb distance identified in the present study. The discrepancy is primarily attributed to the composition of the sample panel, where 77% of the lines (185/240) are inbred, resulting in elevated background LD and consequently extending the observed LD decay distance. Nine SNPs (Table 1) and 93 candidate genes (Supplementary Table S3) were significantly associated with the bolting speed in the data for the year 2022. SNP markers have been used in the genetic mapping of traits of interest in crop species and in molecular marker-based breeding62. The SNP genotyping method has been successfully applied to analyze the genetic diversity of carrots, for development of genomic resources63.

Historical documents and previous studies indicate that plant bolting and flowering are regulated by several endogenous signals64. Histone H4 prevents drought-induced bolting in Chinese cabbage65. A significant number of genes that play a role in the regulation of bolting and flowering have been identified in the model plant Arabidopsis66. Notably, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CO 1 (SOC1), and LEAFY (LFY) are recognized as key contributors to this process67,68. FT is located downstream of the key CO photoperiod pathway gene69. CO can activate FT, and the expression of a large amount of FT is induced in the blade via the phloem apical meristem, and then, this aligns with FD-interdependent partners through protein interactions to activate floral identity genes, such as LFY70,71. Our study identified the candidate gene LOC108205243 in carrots, which is associated with the bolting speed, as belonging to the homologous genes of the RFI2 family (Fig. 5A). Currently, research concerning RFI2 in plants remains limited. RFI2 plays a crucial role in modulating the photoperiodic flowering response in Arabidopsis72. It has the capacity to influence the expression of the genes CO and FT45. Investigations conducted on Arabidopsis and Fragaria vesca have demonstrated that CO and FT are integral to the regulation of plant bolting and flowering processes73,74. In rice, MiR528 has been shown to facilitate heading under long-day conditions through the suppression of OsRFI275. Furthermore, investigations in wheat have identified an interaction between the potential salt-tolerant early-maturing target gene TtPLA1-1 and TtRFI2L, the latter of which is notably enriched in gene ontology (GO) categories related to photoperiod regulation and flowering76. Similarly, the expression levels of the LOC108205243 gene have been found to correlate with the bolting characteristics of three distinct carrot varieties (Fig. 5B, C, D). In current genetic research concerning the vernalization requirements of carrots, the primary determinants influencing the flowering time of this species have been genetically localized to chromosome 24,77,78. In our study, the LOC108205243 gene was identified to be located on chromosome 1, whereas other candidate genes were situated on various chromosomes (Fig. 4). These genes may belong to homologous families or may participate in different regulatory pathways, which warrants further examination. Furthermore, the analysis of protein interaction indicates that the LOC108205243 protein, along with LHW, CDKi7, and other proteins, constitutes a protein interaction network that collectively impacts the bolting trait in carrots. This finding aligns with the results observed in the investigation of stem lodging resistance in ZS11-type Brassica napus79. We propose that LOC108205243 is a prime candidate for engineering, with the dual purpose of molecular breeding for resistance to bolting. Furthermore, drawing upon the significant SNPs identified in this investigation, a variety of high-throughput molecular markers, including Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) and Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequence (CAPS), can be developed. The integration of molecular marker-assisted selection with conventional breeding methodologies has the potential to substantially accelerate the breeding cycle and enhance the efficiency of germplasm improvement. Furthermore, with the increasing adoption of gene editing and related biotechnologies, these SNP loci are also anticipated to function as precise targets for genome editing, thereby advancing the precision breeding of carrots.

Conclusions

In summary, genetic variation provides insights into the correlations among bolting traits. Cluster analysis results emphasized the screening of 71 germplasm resources for resistance bolting. Additionally, through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of 240 carrots,1,222,620 annotated SNPs were obtained for the correlation analysis. Nine of the obtained SNPs were significantly associated with bolting speed, and traits under multiple environments and 93 potential candidate genes were mined. The RING-domain zinc-finger protein LOC108205243 was determined to be primarily involved in the regulation of bolting traits. In conclusion, the SNPs and population gene resources developed in this study are valuable for research on molecular mechanism regulating bolting and for bolting tolerance breeding of carrot.

Data availability

All raw sequences of the 240 carrots have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject number PRJNA1029763. The RNA-seq data analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI SRA repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/), accession numbers of SRP062159.

References

Elshamly, A. M. S. & Nassar, S. M. A. Stimulating growth, root quality, and yield of carrots cultivated under full and limited irrigation levels by humic and potassium applications. Sci. Rep. 13, 14260 (2023).

Villeneuve, F. & Geoffriau, E. Carrot physiological disorders and crop adaptation to stress in Carrots and related Apiaceae crops 156–170CABI, (2020).

Loarca, J., Liou, M., Dawson, J. C. & Simon, P. W. Advancing utilization of diverse global Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) germplasm with flowering habit trait ontology. Front Plant. Sci 15, (2024).

Alessandro, M. S. & Galmarini, C. R. Inheritance of vernalization requirement in Carrot. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 132, 525–529 (2007).

Ou, C. G. et al. Characterising genes associated with flowering time in Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) using transcriptome analysis. Plant. Biol. 19, 286–297 (2017).

Ellison, S. L. et al. Carotenoid presence is associated with the Or gene in domesticated Carrot. Genetics 210, 1497–1508 (2018).

Craigon, J., Atherton, J. G., Basher, E. A. & and Flowering and bolting in carrot. II. Prediction in growth room, glasshouse and field environments. J. Hortic. Sci. 65, 547–554 (1990).

Rubatzky, V. E., Quiros, C. F. & Simon, P. W. Carrots and Related Vegetable Umbelliferae (CABI, 1999).

Linke, B., Alessandro, M. S., Galmarini, C. R. & Nothnagel, T. Carrot floral development and reproductive biology. in The Carrot Genome (eds Simon, P., Iorizzo, M., Grzebelus, D. & Baranski, R.) 27–57 (Springer, (2019).

Hirano, K., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M. & Matsuoka, M. GID1-mediated Gibberellin signaling in plants. Trends Plant. Sci. 13, 192–199 (2008).

Srikanth, A. & Schmid, M. Regulation of flowering time: all roads lead to Rome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2013–2037 (2011).

Cao, S. et al. Genetic architecture underlying light and temperature mediated flowering in Arabidopsis, rice, and temperate cereals. New. Phytol. 230, 1731–1745 (2021).

Song, Y. H., Ito, S. & Imaizumi, T. Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant. Sci. 18, 575–583 (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. TERMINAL FLOWER 1-FD complex target genes and competition with FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nat. Commun. 11, 5118 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. Identification and characterization of the FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family in Petunia. DNA Cell. Biol. 38, 982–995 (2019).

Andrés, F. et al. The sugar transporter SWEET10 acts downstream of FLOWERING LOCUS T during floral transition of Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant. Biol. 20, 53 (2020).

Kim, D. H. & Sung, S. Coordination of the vernalization response through a VIN3 and FLC gene family regulatory network in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 25, 454–469 (2013).

Luo, X. et al. The NUCLEAR FACTOR-CONSTANS complex antagonizes polycomb repression to de-repress FLOWERING LOCUS T expression in response to inductive long days in Arabidopsis. Plant. J. 95, 17–29 (2018).

Wickland, D. P. & Hanzawa, Y. The Flowering locus t/terminal flower 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant. 8, 983–997 (2015).

Cholin, S. S. et al. Deciphering carotenoid and flowering pathway gene variations in Eastern and Western carrots (Daucus Carota L). Genes 15, 1462 (2024).

Shrestha, R., Gómez-Ariza, J., Brambilla, V. & Fornara, F. Molecular control of seasonal flowering in rice, Arabidopsis and temperate cereals. Ann. Bot. 114, 1445–1458 (2014).

Luikart, G., England, P. R., Tallmon, D., Jordan, S. & Taberlet, P. The power and promise of population genomics: from genotyping to genome typing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 981–994 (2003).

Francisco, F. R. et al. Unravelling rubber tree growth by integrating GWAS and biological Network-Based approaches. Front Plant. Sci 12, (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. GWAS of grain color and tannin content in Chinese sorghum based on whole-genome sequencing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 136, 77 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Transcriptome and GWAS analyses reveal candidate gene for seminal root length of maize seedlings under drought stress. Plant. Sci. 292, 110380 (2020).

Zhuang, F. Y., Zhu, D. W. & Ou, C. G. Description Specification and Data Standard of Carrot Germplasm Resources (China Agriculture, 2007).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based Estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Zhang, C., Dong, S. S., Xu, J. Y., He, W. M. & Yang, T. L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786–1788 (2018).

Zhou, X. & Stephens, M. Efficient multivariate linear mixed model algorithms for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods. 11, 407–409 (2014).

Chambers, J. Software for data analysis: programming with R in Software for Data Analysis 139–236 (Springer, (2008).

Bates, D., Maechler, M. & Bolker, B. Lme4. Linear mixed effects models using s4 classeshttp://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html (2011).

Iorizzo, M. et al. A high-quality Carrot genome assembly provides new insights into carotenoid accumulation and asterid genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 48, 657–666 (2016).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools-II: A one for all, all for one bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 16, 1733–1742 (2023).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2– ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J. & Higgins, D. G. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 1, 2–3 (2003).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D607–D613 (2019).

Bryman, A. & Cramer, D. Bivariate analysis in Quantitative data analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A Guide for Social Scientists. (Routledge, (2012).

Wu, X. et al. Genetic diversity analysis of agronomic traits in local germplasm of Adzuki bean in Heilongjiang Province. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 50, 1–11 (2019).

Chen, M. & Ni, M. RFI2, a RING-domain zinc finger protein, negatively regulates CONSTANS expression and photoperiodic flowering. Plant. J. 46, 823–833 (2006).

Domblides, A. & Domblides, E. Rapid genetic assessment of Carrot varieties based on AFLP analysis. Horticulturae 9, 298 (2023).

Farwan, K., Devi, R. & Dhillon, T. S. Elucidation of genetic variability, heritability, correlation and path coefficient in Carrot (Daucus Carota L). Appl. Biol. Res. 25, 102–109 (2023).

Matsoukas, I. G., Massiah, A. J. & Thomas, B. Florigenic and antiflorigenic signaling in plants. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 53, 1827–1842 (2012).

Bao, S., Hua, C., Shen, L. & Yu, H. New insights into Gibberellin signaling in regulating flowering in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 62, 118–131 (2020).

Zhao, Z. et al. Population structure analysis to explore genetic diversity and geographical distribution characteristics of cultivated-type tea plant in Guizhou plateau. BMC Plant. Biol. 22, 55 (2022).

Egbadzor, K. F. et al. Diversity in 113 Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp] accessions assessed with 458 SNP markers. SpringerPlus 3, 541 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure analyses in the alpine Plum (Prunus brigantina Vill.) confirm its affiliation to the Armeniaca section. Tree Genet. Genomes. 17, 2 (2021).

Bernard, A., Barreneche, T., Donkpegan, A., Lheureux, F. & Dirlewanger, E. Comparison of structure analyses and core collections for the management of walnut genetic resources. Tree Genet. Genomes. 16, 76 (2020).

Pascual, L. et al. Development of a multipurpose core collection of bread wheat based on High-Throughput genotyping data. Agronomy 10, 534 (2020).

Meegahakumbura, M. K. et al. Domestication origin and breeding history of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) in China and India based on nuclear microsatellites and CpDNA sequence data. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 2270 (2018).

Fan, L. et al. A genome-wide association study uncovers a critical role of the RsPAP2 gene in red-skinned Raphanus sativus L. Hortic. Res. 7, 164 (2020).

Coe, K. et al. Population genomics identifies genetic signatures of Carrot domestication and improvement and uncovers the origin of high-carotenoid orange Carrots. Nat. Plants. 9, 1643–1658 (2023).

Rong, J. et al. New insights into domestication of Carrot from root transcriptome analyses. BMC Genom. 15, 895 (2014).

Clotault, J., Geoffriau, E., Lionneton, E., Briard, M. & Peltier, D. Carotenoid biosynthesis genes provide evidence of geographical subdivision and extensive linkage disequilibrium in the Carrot. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121, 659–672 (2010).

Soufflet-Freslon, V. et al. Functional gene polymorphism to reveal species history: the case of the CRTISO gene in cultivated carrots. PLoS ONE. 8, e70801 (2013).

Brainard, S. H., Ellison, S. L., Simon, P. W., Dawson, J. C. & Goldman, I. L. Genetic characterization of Carrot root shape and size using genome-wide association analysis and genomic-estimated breeding values. Theor. Appl. Genet. 135, 605–622 (2022).

Su, J. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies favorable SNP alleles and candidate genes for waterlogging tolerance in chrysanthemums. Hortic. Res. 6, 21 (2019).

Iorizzo, M. Recent advances in Carrot genomics. Acta Hortic. 75–90. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2019.1264.9 (2019).

Wigge, P. A. et al. Integration of Spatial and Temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309, 1056–1059 (2005).

Xin, X. et al. A histone H4 gene prevents drought-induced bolting in Chinese cabbage by attenuating the expression of flowering genes. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 623–635 (2021).

Fornara, F., de Montaigu, A., Coupland, G. & SnapShot Control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Cell 141, 550–550e2 (2010).

Mouradov, A., Cremer, F. & Coupland, G. Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant. Cell. 14, S111–S130 (2002).

Parcy, F. Flowering: a time for integration. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 49, 585–593 (2005).

Adrian, J. et al. Cis -Regulatory elements and chromatin state coordinately control Temporal and Spatial expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T In Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 22, 1425–1440 (2010).

Halliday, K. J., Salter, M. G., Thingnaes, E. & Whitelam, G. C. Phytochrome control of flowering is temperature sensitive and correlates with expression of the floral integrator FT. Plant. J. 33, 875–885 (2003).

Abe, M. et al. FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309, 1052–1056 (2005).

Chen, M., Ni, M. & RED AND FAR-RED INSENSITIVE 2, a RING-Domain zinc finger Protein, mediates Phytochrome-Controlled seedling deetiolation responses. Plant. Physiol. 140, 457–465 (2006).

Cheng, X. & Wang, Z. Overexpression of COL9, a CONSTANS-LIKE gene, delays flowering by reducing expression of CO and FT in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant. J. 43, 758–768 (2005).

Prisca, M. et al. Blue and far-red light control flowering time of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) distinctively via CONSTANS (CO) and FLOWERING LOCUS T1 (FT1) in the background of sunlight mimicking radiation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 198, 104866 (2022).

Yang, R. et al. Fine-tuning of MiR528 accumulation modulates flowering time in rice. Mol. Plant. 12, 1103–1113 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. A novel phospholipase A1 gene from tritipyrum improves wheat early ripening and salt tolerance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 73, 17713–17729 (2025).

Wohlfeiler, J., Alessandro, M. S., Cavagnaro, P. F. & Galmarini, C. R. Gradient of vernalization requirement in Carrot cultivars from diverse geographical origins. Crop Sci. 61, 3373–3381 (2021).

Wohlfeiler, J., Alessandro, M. S., Morales, A., Cavagnaro, P. F. & Galmarini, C. R. Vernalization Requirement, but not Post-Vernalization day Length, conditions flowering in Carrot (Daucus Carota L). Plants 11, 1075 (2022).

Tian, Z. et al. Integrating biochemical and anatomical characterizations with transcriptome analysis to dissect superior stem strength of ZS11 (Brassica napus). Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1144892 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks everyone who contributed to this article.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Research Foundation of Qinghai Provincial (Grant No. 2021-ZJ-930) and the Major Science and Technology Special Project of Xining: Industrial Technology Collaborative Innovation Center of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Cool-Climate Vegetables (Grant No. 2022-Z-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. K. wrote the main manuscript text and contributed to the conception of the study. X. K., J. W., X. Y., F. Z., H. Z., S. X. and C. O. performed the experiments and the data analyses. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, X., Wu, J., Yan, X. et al. Genome-wide association study to dissect the genetic architecture of bolting-related traits in carrot (Daucus carota). Sci Rep 15, 42864 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26927-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26927-9