Abstract

It has been suggested that readers encode letter positions flexibly during word recognition, as evidenced by studies showing that misspelled words can still be read naturally (e.g., transposed letter effects). On the other hand, in some non-Roman alphabetic writing systems, such as Korean Hangul, syllables rather than individual letters within a word might be the main source of confusability, called the transposed syllable (TS) effect. Despite evidence supporting the existence of the TS effect, its specific characteristics remain largely unexplored. Here, we studied variables that may mediate the TS effect in Korean Hangul. In the first two experiments, we used the masked priming lexical decision task and observed that the TS effect (i.e., faster lexical decision when the prime was the internal TS version of the target than when it was the replaced-syllable version) was apparent only for high-frequency Korean Hangul stimuli. We also found that the priming effect on lexical decisions depends on the distance between the transposed syllables. Lastly, in Experiment 3, we demonstrated that the TS effect might also emerge at the pre-lexical perceptual level using the perceptual matching task. Our findings indicate that multiple stages of information processing support the TS effect in Korean Hangul.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precise encoding of letter position seems critical for word recognition1,2. Nevertheless, when reading a word, people often confuse a letter in a position with another letter in a different position. For example, you may misread “a trial” as “a trail” or even a pseudoword such as “acheive” could be read as “achieve”. A growing body of evidence supports this transposed-letter (TL) effect, demonstrating that pseudowords created by transposing two letters within a real word elicit stronger lexical activation than those produced via letter replacement3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. It implies that people tolerate imprecision in letter positions to some extent during word recognition.

This phenomenon is incompatible with slot-coding models, which assume that each letter in a word occupies a rigid, position-specific slot, thereby tightly coupling letter identity with letter position (e.g., Interactive activation model2; dual-route cascaded model1). To account for the limitations of slot-coding models, alternative frameworks have incorporated greater flexibility in letter position encoding. In open-bigram schemes12,13,14, a TL pseudoword JUGDE is perceived as highly similar to its base word JUDGE because they share nearly all of their open bigrams, differing only in a pair such as GD versus DG. In contrast, a replaced-letter (RL) pseudoword like JUNPE shares significantly fewer bigrams with JUDGE (only three out of ten), resulting in lower perceived similarity. The overlap model8 posits that each letter in a word has a distribution over position so that the representation of one letter could extend into neighboring letter positions. In the spatial coding model15, activation gradient for the letters in a word varies based on their relative position, such that a TL pseudoword and its base word yield highly similar activation patterns, leading to confusion. The Bayesian reader model16,17 assumes that readers make near-optimal decisions by accumulating noisy perceptual input. TL effects, under this view, emerge from early-stage uncertainty in mapping noisy representations of letter identity and order onto serially ordered orthographic codes.

Research has identified a variety of factors that modulate the TL effect, and we highlight those of particular relevance to our study. First, the TL effect varies as a function of the lexical frequency of the base words: The effect is more prominent for TL pseudowords derived from high-frequency words than for those derived from low-frequency words9,18,19,20. It indicates that high-frequency TL pseudowords produce greater activation of their base words compared to low-frequency TL pseudowords. The influence of lexical frequency may be explained by models such as the Bayesian reader. When the visual input is noisy, as in the case of letter transpositions, lexical frequency modulates the prior probabilities of word activation, making high-frequency words more likely to be selected. This leads to stronger TL effects for pseudowords derived from high-frequency words, as they are more readily activated under conditions of uncertainty, thereby increasing the likelihood of misidentification and lexical competition. Second, the magnitude of the TL effect is modulated by the positions of the transposed letters. The effect is typically stronger when the middle two letters are transposed, compared to transpositions involving the first or the last two letters3,4,11. This result is consistent with the idea that the quality of letter information is better at the beginnings and ends of words than in the middle21,22,23,24,25,26, probably because external letters are less affected by lateral interference from neighboring letters. In addition, transposing nonadjacent letters can also induce the TL effect27,28,29, although the effect is generally weaker than when adjacent letters are transposed6,8,30,31. Several models can account for this pattern. For instance, in open bigram models, nonadjacent transpositions result in fewer shared bigrams with the base word, reducing activation. Similarly, in the overlap model, the spatial distributions of nonadjacent letters overlap less, leading to lower perceptual similarity.

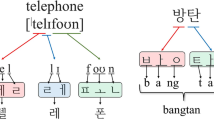

However, the TL effects do not seem to generalize across different cultures32,33. For instance, studies reported that there is scarce evidence of the TL effect in the Korean writing system, Hangul. Unlike in English, swapping the onsets, codas, or codas for onsets across the first and second syllables of Hangul words or exchanging the onset and coda within a syllable barely produced the TL effects34,35,36,37. Do these results mean that Hangul has strict position encoding? One thing to note is the unique status of Hangul, being both alphabetic and syllabic. Hangul letters are joined into syllable blocks, and the syllable blocks are physically separated from each other. In addition, the letter position within a syllable is fixed and unambiguous. This positional unambiguity within and across the syllable boundary may prevent a TL effect in Hangul. These unique features of Hangul may make the syllable, rather than the letter, an important and basic unit of word recognition38. Interestingly, some studies showed that there might be flexible syllable position representations in Hangul39,40,41,42 and in other Asian languages sharing similar syllabic units, such as Chinese characters43 and Japanese kana44, whereas Roman alphabet writing systems do not show such transposed-syllable (TS) effects45.

While TL effects have been studied extensively, relatively little is known about the nature of TS effects–specifically, how they are modulated by factors like lexical frequency and perceptual similarity, and whether they originate at lexical or pre-lexical levels. The present study investigates the TS effect and its properties in Korean Hangul through a series of three experiments. In Experiment 1, we used a masked priming lexical decision task to assess whether the TS effect is modulated by lexical frequency, hypothesizing a stronger effect for high-frequency Hangul stimuli. Experiment 2 extended this by examining whether the distance between the transposed syllables influences the strength of the priming effect. Drawing on findings from TL research, we predicted that adjacent internal syllable transpositions would produce the most robust priming6,8,30,31. Lastly, Experiment 3 tested whether TS effects could also arise at a pre-lexical, perceptual level. A recent study using a lexical decision task suggested that the TS effect in Hangul may be rooted in early perceptual processing42. To test this more directly, we employed a simple perceptual matching task46,47, which minimizes lexical involvement and offers a more focused assessment of pre-lexical contributions to the TS effect.

Methods

Experiment 1

Participants

Forty naïve participants from Pusan National University, including undergraduate students and graduates, participated in the experiment (12 males and 28 females, mean age 22.08 years, SD 3.11 years). They had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and normal color vision. All participants were native Korean speakers, and only one was left-handed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Thirty-five participants were paid for their participation (10,000 KRW per participation), and five additional participants received course credits. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (2019_86_HR) and the Departmental Review Board of Pusan National University. All aspects of the study were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of Departmental Review Committee of Pusan National University.

Apparatus and stimuli

The experiment was conducted in a silent, dark room. Participants sat 66 cm away from a BENQ LCD monitor (XL2740, 27-inch, 1920 × 1080, 120 Hz), and their heads were stabilized on a head-and-chin rest. We used MATLAB (The MathWorks Corp., MA, USA) and the Psychophysics Toolbox48,49 to create and present stimuli.

In the present study, we used Hangul Eojeol rather than Hangul words as stimuli. Eojeol is a linguistic unit consisting of lexical (e.g., words) and/or grammatical (e.g., postpositions) morphemes, and a space separates each Eojeol. For example, ‘어머니는’ in Fig. 1 is the combination of ‘어머니’ (the noun meaning mother) and ‘는’ (the postpositional particle making a word a subject in a sentence). Since there are not enough four- or five-syllable Hangul words to be used in our experiments, we employed Eojeol to select multisyllabic stimuli more efficiently and increase statistical power.

As target stimuli, we selected 200 high-frequency (ranging from 1022 to 14,101, mean (M) = 2255.79, SD = 1657.10) and 200 low-frequency (ranging from 9 to 395, M = 13.11, SD = 27.31) four-syllable Hangul Eojeol from the Sejong Corpus, a part of the twenty-first century Sejong Project (National Institute of Korean Language, Republic of Korea). We also created 200 meaningless four-syllable Eojeol for ‘illegal’ responses in the lexical decision task.

There were four prime conditions. First, in the identical condition, a target and a prime were the same (e.g., 어머니는–어머니는 (direct translation is ‘a mother is’)). Second, in the internal transposed-syllable condition (TS-internal), the second and third syllables of the target were transposed (e.g., 어니머는). Third, in the replaced-syllable condition (RS), the second syllable of the target was substituted with another syllable (e.g., 어정니는). Fourth, in the external transposed-syllable condition (TS-external), the first and last syllables of the target were transposed (e.g., 는머니어). To assess the TS effect, we compared reaction times (RTs) in the TS-internal condition with those in the RS condition3,4,5,6,7,8. All the prime stimuli were meaningless, except for those in the identical condition. White Hangul letter strings in Nanum Gothic font (each syllable block subtended 1.91°) were presented on a black background. Note that throughout our experiments, Hangul Eojeol stimuli were randomly assigned to prime conditions for each participant, rather than using a fixed list of Eojeol stimuli for each condition.

Procedure

Each trial began with a white fixation cross presented for 1000ms (Fig. 1). A prime appeared for 50ms, preceded by the 500-ms display of six hash marks (######) that functioned as a pre-mask stimulus. After a 100-ms blank interval, a target was presented. Participants were required to judge as quickly and as accurately as possible if the target was a legal Hangul Eojeol or not. They pressed the left or right arrow key to report ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’, respectively, and then the color of the fixation cross turned to green (correct) or red (incorrect) for 500ms to provide feedback to the judgment. If participants did not respond within 1500ms after target onset, they received feedback for incorrect judgments. Then, the trial was discarded, and the next trial automatically began. The inter-trial interval was randomly chosen between 1000 and 1500ms. Each participant performed 20 practice trials and then performed 600 main experimental trials (three Eojeol conditions (high-frequency, low-frequency, illegal) x four prime conditions × 50 Eojeol).

Experiment 2

Participants

Thirty-eight naïve undergraduate students of Pusan National University participated in the experiment (8 males and 30 females, mean age 21.08 years, SD 2.16 years). They had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and normal color vision. All participants were native Korean speakers, and all but seven participants were right-handed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. They received course credits for their participation. All procedures were approved by the Departmental Review Board of Pusan National University. All aspects of the study were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of Departmental Review Committee of Pusan National University.

Apparatus and stimuli

The apparatus was the same as in Experiment 1. As target stimuli, we selected 200 high-frequency (ranging from 198 to 3954, M = 514.46, SD = 466.32) and 200 low-frequency (ranging from 4 to 108, M = 6.51, SD = 9.59) Hangul Eojeol with five syllables from the Sejong Corpus. We also created 200 meaningless five-syllable Eojeol for ‘illegal’ responses in the lexical decision task.

To create prime stimuli, adjacent internal syllables of target stimuli (e.g., 우리나라의, a direct translation is ‘of our country’) were transposed (second and third syllables (TS 2–3), e.g., 우나리라의, and third and fourth syllables (TS 3–4), e.g., 우리라나의), nonadjacent internal syllables were transposed (second and fourth syllables (TS 2–4), e.g., 우라나리의), and external syllables were transposed (TS 1–5, e.g., 의리나라우). All the prime stimuli were meaningless Eojeol. White Hangul letter strings in Nanum Gothic font (each syllable block subtended 1.91°) were presented on a black background.

Procedure

The task and its procedure were the same as those in Experiment 1.

Experiment 3

Participants

Thirty naïve undergraduate students of Pusan National University participated in the experiment (10 males and 20 females, mean age 20.77 years, SD 2.13 years). They had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and normal color vision. All participants were native Korean speakers. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. They received course credits for their participation. All procedures were approved by the Departmental Review Board of Pusan National University. All aspects of the study were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of Departmental Review Committee of Pusan National University.

Apparatus and Stimuli

The same apparatus was used as in Experiments 1 and 2. We selected 180 high-frequency (ranging from 1127 to 14,101, M = 2382.40, SD = 1700.24), 180 low-frequency (ranging from 9 to 395, M = 13.23, SD = 28.72), and 180 illegal Eojeol from the stimulus pool of Experiment 1. In addition, the primes and targets used in Experiment 1 were relabeled as the targets and references, respectively.

There were four target conditions. In the identical condition, references and targets were the same. To create the targets in the TS-internal condition, the second and third syllables of each reference were transposed. For the targets in the RS condition, the second syllable of each reference was substituted with another syllable. Lastly, we transposed the first and last syllables of each reference to create the targets in the TS-external condition. All the target stimuli were meaningless, except for those in the identical condition. White Hangul letter strings in Nanum Gothic font (each syllable block subtended 1.91°) were presented on a black background.

Procedure

Each trial began with a white fixation cross presented for 1000ms (Fig. 2). A reference and a target appeared for 200ms sequentially, and the 200-ms display of six hash marks was embedded between the two stimuli to demarcate them. Finally, the fixation cross reappeared, and participants reported whether the reference and target were visually the same or different as quickly and as accurately as possible. They pressed the left or right arrow key to report “different” or “same”, respectively, and then the color of the fixation cross turned to green (correct) or red (incorrect) for 500ms to provide feedback to the response. If participants could not respond within 1500ms after the target disappeared, they received feedback for incorrect responses. Then, the trial was discarded, and the next trial automatically began. The inter-trial interval was randomly chosen between 1000 and 1500ms. Each participant performed 30 practice trials and then performed 540 main experimental trials (three Eojeol conditions (high-frequency, low-frequency, and illegal) × 90 trials for the identical condition and 30 trials for each of the other three target conditions).

Results

Experiment 1: TS effects are affected by the lexical frequency of Korean Hangul Eojeol

Across all experiments, we fit a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) to RT data and a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) to accuracy data, using the lme4 and lmerTest packages in the R statistical computing environment50. The GLMM was specified with a binomial distribution and logit link function, appropriate for binary accuracy outcomes. In both models, Eojeol frequency and prime condition were included as fixed effects, and participants and Eojeol were included as random effects with random intercepts51. For post-hoc analyses, estimated marginal means (EMMs) were computed using the emmeans package, and pairwise comparisons were conducted with the Bonferroni corrections.

In this experiment, only high- and low-frequency Eojeol conditions were included in the analyses, as our primary aim was to investigate whether and how Eojeol frequency modulates the TS effect. Data on illegal Eojeol conditions are available in Tables S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Information.

RTs were significantly faster for high-frequency Eojeol compared to low-frequency Eojeol (b = − 48.80, SE = 3.47, z = − 14.077, p = 5.293 × 10−45, Fig. 3A). For high-frequency Eojeol, RTs were fastest in the identical condition, and then they gradually increased in the following order: TS-internal, RS, and TS-external conditions (all ps < 0.001). Faster RTs in the TS-internal condition compared to the RS condition (b = − 18.42, SE = 3.89, z = − 4.730, p = 1.345 × 10−5)–a typical marker of the TL effect3,4,5,6,7,8–suggest that syllable positions are represented more flexibly when internal syllables are transposed than when a syllable is replaced. However, for low-frequency Eojeol, no significant RT difference was found between the TS-internal and RS conditions (b = − 0.54, SE = 3.97, z = − 0.137, p = 1). RTs in the TS-external condition were significantly slower than those in the other conditions, regardless of Eojeol frequency (all ps < 0.001).

(A) Mean RTs of the masked priming lexical decision task in Experiment 1. For high-frequency Eojeol (red circles), RTs were significantly faster when internal syllables were transposed (TS-internal) than when a syllable was replaced (RS). In contrast, for low-frequency Eojeol (blue circles), there was no significant difference in RTs between the two conditions. (B) Mean accuracy of the masked priming lexical decision task in Experiment 1. For high-frequency Eojeol, accuracy was not significantly affected by the prime condition. In contrast, for low-frequency Eojeol, accuracy was highest when the prime and target stimuli were identical and lowest when internal syllables were transposed. Error bars indicate the SEM.

Accuracy was higher for high-frequency Eojeol than for low-frequency Eojeol (b = 1.36, SE = 0.24, z = 5.548, p = 2.897 × 10−8, Fig. 3B). For high-frequency Eojeol, accuracy did not significantly differ across all prime conditions (all ps > 0.1). For low-frequency Eojeol, accuracy in the TS-internal condition was significantly lower than that in the identical (b = − 2.35, SE = 0.32, z = − 7.438, p = 6.131 × 10−13) and RS conditions (b = − 1.13, SE = 0.21, z = − 5.364, p = 4.877 × 10−7) but not statistically different from that in the TS-external condition (b = − 0.32, SE = 0.17, z = − 1.894, p = 0.349).

Experiment 2: Adjacent syllable transpositions induce greater priming effects than nonadjacent ones

Since we used four-syllable Eojeol in Experiment 1, the internal transposition was limited to adjacent syllables (specifically, the second and third syllables). However, prior research on the TL effect has shown that the distance between transposed letters can modulate the effect6,8,30,31. This raised the question of whether the TS effect in Hangul is similarly sensitive to the positional distance between transposed syllables. To explore this, Experiment 2 employed five-syllable Eojeol, allowing for a broader range of syllable transpositions.

RTs were faster for high-frequency Eojeol compared to low-frequency Eojeol (b = − 48.32, SE = 3.82, z =− 12.659, p = 9.923 × 10−37, Fig. 4A). Regardless of Eojeol frequency, RTs were fastest in the TS 3–4 condition, and they increased in the following order: TS 2–3, TS 2–4, and TS 1–5 (all ps < 0.001). These results demonstrate that the priming effect is stronger for transpositions involving internal syllables than external ones, and is particularly pronounced when the transposed internal syllables are adjacent rather than nonadjacent.

(A) Mean RTs of the masked priming lexical decision task in Experiment 2. RTs were significantly faster when adjacent (TS 3–4, TS 2–3) than nonadjacent internal syllables (TS 2–4) were transposed, regardless of Eojeol frequency. (B) Mean accuracy of the masked priming lexical decision task in Experiment 2. Corresponding to the RT data, accuracy was higher when adjacent internal syllables were transposed compared to nonadjacent internal syllables. Error bars indicate the SEM.

Accuracy was higher for high-frequency Eojeol compared to low-frequency Eojeol (b = 1.42, SE = 0.21, z = 6.774, p = 1.251 × 10−11, Fig. 4B). Accuracy in the TS 3–4 condition was not statistically different from that in the TS 2–3 condition (b = − 0.03, SE = 0.29, z = − 0.114, p = 1), but it was higher than accuracy in the other conditions (all ps < 0.005). Accuracy in the TS 2–3 condition was significantly higher than that in the TS 2–4 (b = 0.85, SE = 0.26, z = 3.286, p = 0.006) and TS 1–5 conditions (b = 0.82, SE = 0.26, z = 3.178, p = 0.009). In addition, there was no significant accuracy difference between TS 2–4 and TS 1–5 conditions (b = − 0.02, SE = 0.19, z = − 0.130, p = 1). Both RT and accuracy data suggest that the priming effect is stronger when the adjacent internal syllables are transposed than when non-adjacent syllables are transposed.

Experiment 3: TS effects might be affected by perceptual representation

While Experiments 1 and 2 pointed toward a lexical locus for the TS effect, they did not rule out the potential contribution of lower-level perceptual processes. To address this, Experiment 3 investigated whether TS effects could also emerge at a pre-lexical stage using a simple perceptual matching task46,47. A recent study suggested that the TS effect in Korean Hangul may be partly driven by perceptual processes, as evidenced by slower lexical decisions to TS stimuli presented in the left visual field42. This result is consistent with prior findings that the right hemisphere is involved in early visual processing52 and holistic word processing53,54. However, because lexical decision tasks involve multiple processing levels, these hemispheric differences could reflect more than just perceptual factors. Additionally, parafoveal stimulus presentation may have introduced confounds related to reduced spatial resolution. To isolate perceptual contributions more directly, we presented stimuli foveally and asked participants to compare their visual properties using a simple matching task. Importantly, this task is different from the masked priming same-different task used in the previous studies 55,56.

RTs were faster for high-frequency Eojeol compared to low-frequency Eojeol (b = − 10.63, SE = 3.15, z = − 3.376, p = 0.0007, Fig. 5A). In addition, RTs were slowest in the TS-internal condition regardless of Eojeol frequency (all ps < 0.001). Notably, RTs were faster for high-frequency than low-frequency Eojeol in the identical (b = − 33.12, SE = 3.95, z = − 8.376, p = 5.487 × 10−17) and RS (b = − 18.61, SE = 6.85, z = − 2.717, p = 0.007) conditions. Faster RTs for high-frequency Eojeol in the identical condition may indicate that the task does not purely reflect pre-lexical processing.

(A) Mean RTs of the simple perceptual matching task in Experiment 3. RTs were the slowest when the internal syllables were transposed (TS-internal), regardless of Eojeol frequency. (B) Mean accuracy of the simple perceptual matching task in Experiment 3. Corresponding to the RT data, accuracy was the lowest when the internal syllables were transposed. Error bars indicate the SEM.

Accuracy did not differ by Eojeol frequency (b = 0.10, SE = 0.14, z = 0.714, p = 0.475), but it was lowest in the TS-internal condition for both Eojeol frequencies (all ps < 0.001, Fig. 5B). Accuracy was not statistically different across the other target conditions.

General discussion

We explored variables that potentially influence the transposed-syllable (TS) effect in Korean Hangul. In Experiment 1, we replicated the TS effect previously reported in Korean Hangul studies39,40,41,42, and further showed that lexical frequency modulates the TS effect. In the masked priming lexical decision task, participants responded faster to high-frequency Eojeol than to low-frequency ones across all prime conditions. However, a significant TS effect–measured by the RT difference between the TS-internal and replaced-syllable (RS) conditions–emerged only for high-frequency Eojeol. This pattern corresponds to prior findings on lexical frequency-mediated TL effects9,18,19,20. In particular, Vergara-Martínez et al.20 reported that TL pseudowords derived from high-frequency words elicited smaller N400 amplitudes than their RL counterparts, while TL and RL pseudowords derived from low-frequency words elicited comparable N400 responses. These results suggest that lexical frequency modulates the activation of lexical-semantic representations–a mechanism that may also underlie the TS effect in Hangul.

Experiment 2 showed that the distance between the transposed syllables modulates the degree of the priming effect on lexical decisions. Lexical decisions were significantly faster when adjacent internal syllables were transposed than when nonadjacent syllables were transposed, consistent with the previous findings on the TL effects6,8,30,31. We also found that transpositions involving later syllables (e.g., TS 3–4) produced stronger priming effects than those involving earlier ones (e.g., TS 2–3). Although the open bigram and overlap models can explain increased priming effects for adjacent internal transpositions, to our knowledge, they do not appear to account for differences based on the specific positions of those transpositions. Interestingly, our findings may resonate with earlier observations reported by Perea23. In that study, participants sequentially viewed two five-letter English words: a clearly visible prime followed by a briefly presented target that differed by a single letter. They were then asked to identify the target word. Target identification was impaired when the letter difference occurred in the third or fourth position compared to a control condition in which the prime and target shared no letters in corresponding positions. Despite differences in stimuli and experimental paradigms, both Perea23 and our study suggest that the weight assigned to each letter or syllable may vary depending on its serial position (c.f., spatial coding model15). One possible explanation is that the second position in five-letter words or in five-syllable Eojeol is particularly salient, as it overlaps with the optimal viewing position, which lies slightly to the left of the word’s center in left-to-right scripts57. Consequently, transposing the second and third syllables may be more noticeable, thereby reducing the TS effect. Future research could investigate whether the pattern of effects observed in our study would be mirror-reversed in right-to-left scripts.

Experiment 3 indicates that perceptual similarity between Hangul Eojeol and their TS-internal counterparts plays a role in the TS effect. Specifically, RTs of the simple perceptual matching task were the slowest in the TS-internal condition for both high-frequency and low-frequency Eojeol. This result supports the previous finding that the TS effect may emerge at an early perceptual level42. However, the observation of faster RTs for high-frequency compared to low-frequency Eojeol in the identical condition implies that the lexical properties of Hangul stimuli still influence task performance. High-frequency Eojeol may benefit from faster recognition, likely due to stronger and more readily accessible lexical representations, even in tasks that do not explicitly require lexical processing. We also performed additional analyses using the data in the illegal Eojeol condition (see the Supplementary Information for details). Even though illegal Eojeol stimuli were meaningless and random, the responses to illegal Eojeol were the slowest and worst in the TS-internal condition, bolstering the role of perceptual factors. However, RTs in the high- and low-frequency Eojeol conditions were significantly faster than those in the illegal Eojeol condition. It provides converging evidence that both perceptual and lexical processes are intertwined in our data.

The TL effect has been attributed either to noise in early perceptual encoding processes8,15,16, or to the involvement of higher-level orthographic representations, such as open bigrams12. In line with our findings, evidence from Roman alphabetic writing systems suggests that these two accounts may coexist. For instance, manipulating the visual presentation of words reduces TL effects compared to standard formats, but the effects are not entirely eliminated58,59. In the case of Korean Hangul, Kim and colleagues42 proposed that the TS effect is primarily rooted in early perceptual processing. Lexical decisions for TS stimuli were significantly slower than for control stimuli when presented in the left visual field, a pattern consistent with the right hemisphere’s role in early visual52 and holistic word processing53,54. However, the TS effect persisted, albeit to a lesser extent, even when stimuli were presented in the right visual field, suggesting that higher-level processes may also contribute to the TS effect.

There are conflicting findings regarding the TS effect in Korean Hangul. While studies using unprimed lexical decision tasks with four-syllable Eojeol have reported slower RTs to correctly reject TS (internal) Eojeol compared to control Eojeol39,40,41, Rastle et al.36 found no facilitation in lexical decisions when TS versions of disyllabic Hangul words were used as primes. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences between the tasks (primed vs. unprimed) and characteristics of experimental stimuli. Nearly 30% of disyllabic Hangul words are TS anagrams of other words36, whereas this is true for less than 0.3% of four-syllable words36,56. Therefore, a more rigid representation of syllable blocks may be necessary for shorter words to prevent misperception, but this rigidity may be less important for recognizing longer words. In addition, transposing syllables in disyllabic Hangul words corresponds to the TS-external condition in our study, which did not facilitate lexical decisions.

We speculate that syllables, rather than individual letters, may serve as the basic processing units in Korean Hangul word recognition38. Unlike in alphabetic languages, where the TL effects are robust, prior studies have shown that swapping letters within or across syllables in Korean Hangul does not produce strong TL effects34,35,36,37. In contrast, TS effect are more robust39,40,41,42, suggesting that letter-level confusability is reduced in Korean Hangul. This may be due to the structural property of Hangul where letters are not linearly concatenated but are instead organized into spatially distinct syllable blocks with predictable internal structure (e.g., fixed positions for consonants and vowels). These syllable blocks are visually salient and often perceived as single, coherent units or ‘chunks’, making them easy to segment. According to Dehaene et al.’s framework60, such syllable blocks may be represented via pooled activation from multiple letter detectors. In Korean Hangul, these letter detectors likely operate in a location-specific manner, given that letter positions within a syllable block are tightly constrained. Subsequently, local bigram detectors are fed from letter detectors to achieve partial location invariance. Interesting future research is to test whether analogous ‘syllable bigram detectors’ exist in the Hangul reading brain. Based on our results and the previous literature on the TS effect, syllable-level bigram is a good fit for open bigrams in Korean Hangul, and thus, we would expect that syllable-based neural coding in Korean Hangul may parallel the letter-based neural coding in Western scripts. Indeed, stronger priming effects observed for adjacent syllable transpositions than nonadjacent ones in our results are consistent with the predictions of open-bigram12,13,14 and overlap8 models. Hence, if these models are adapted to operate at the syllable level, they would be able to account for the TS effect in Korean Hangul.

Research on the TS effect has real-world implications. In human–computer interaction, systems such as spell-checkers and optical character recognition (OCR) software can leverage insights from TS research to better model human reading patterns and make more adaptive corrections based on how people actually read. One might also ask whether the TS effect can serve as a tool for assessing individual reading skills. This question is based on the idea that the TS effect may reflect automatic orthographic processing, a critical component of skilled visual word recognition. However, the current evidence on this question remains inconclusive. In the TL literature, several studies have investigated the relationship between the TL effect and reading skills, but the results are mixed. Some studies reported that letter position encoding becomes more flexible as reading skills improve61,62,63, while others found a negative correlation5,64,65. A more recent study found no significant association between the two66. Taken together, these findings suggest that while TL and TS effects offer valuable insights into reading processes, their utility as indicators of reading skills remains uncertain and warrants further investigation.

Data availability

All experimental data generated and analyzed during the current study and analysis codes are available in the study’s OSF repository (https:/osf.io/y682n).

References

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R. & Ziegler, J. DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 108, 204–256 (2001).

McClelland, J. L. & Rumelhart, D. E. An interactive activation model of context effects in letter perception: I. An account of basic findings. Psychol. Rev. 88, 375–407 (1981).

Chambers, S. M. Letter and order information in lexical access. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 18, 225–241 (1979).

Perea, M. & Lupker, S. J. Does jugde activate court? Transposed-letter similarity effects in masked associative priming. Mem. Cognit. 31, 829–841 (2003).

Acha, J. & Perea, M. The effects of length and transposed-letter similarity in lexical decision: Evidence with beginning, intermediate, and adult readers. Br. J. Psychol. 99, 245–264 (2008).

Massol, S., Duñabeitia, J. A., Carreiras, M. & Grainger, J. Evidence for letter-specific position coding mechanisms. PLoS ONE 8, e68460 (2013).

Duñabeitia, J. A., Dimitropoulou, M., Grainger, J., Hernández, J. A. & Carreiras, M. Differential sensitivity of letters, numbers, and symbols to character transpositions. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 1610–1624 (2012).

Gomez, P., Ratcliff, R. & Perea, M. The overlap model: A model of letter position coding. Psychol. Rev. 115, 577–600 (2008).

Andrews, S. Lexical retrieval and selection processes: Effects of transposed-letter confusability. J. Mem. Lang. 35, 775–800 (1996).

Forster, K. I., Davis, C., Schoknecht, C. & Carter, R. Masked priming with graphemically related forms: Repetition or partial activation?. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 39, 211–251 (1987).

Perea, M. & Lupker, S. J. Transposed-letter confusability effects in masked form priming. In Masked Priming: The State of the Art (eds Kinoshita, S. & Lupker, S. J.) 97–120 (Psychology Press, 2003).

Grainger, J. & van Heuven, W. J. B. Modeling letter position coding in printed word perception. In Mental lexicon: Some words to talk about words 1–23 (ed. Bonin, P.) (Nova Science, 2004).

Whitney, C. How the brain encodes the order of letters in a printed word: The seriol model and selective literature review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 8, 221–243 (2001).

Grainger, J. & Whitney, C. Does the huamn mnid raed wrods as a wlohe?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 58–59 (2004).

Davis, C. J. The spatial coding model of visual word identification. Psychol. Rev. 117, 713–758 (2010).

Norris, D. The Bayesian reader: Explaining word recognition as an optimal Bayesian decision process. Psychol. Rev. 113, 327–357 (2006).

Norris, D. & Kinoshita, S. Reading through a noisy channel: Why there’s nothing special about the perception of orthography. Psychol. Rev. 119, 517–545 (2012).

O’Connor, R. E. & Forster, K. I. Criterion bias and search sequence bias in word recognition. Mem. Cognit. 9, 78–92 (1981).

Perea, M., Rosa, E. & Gómez, C. The frequency effect for pseudowords in the lexical decision task. Percept. Psychophys. 67, 301–314 (2005).

Vergara-Martínez, M., Perea, M., Gómez, P. & Swaab, T. Y. ERP correlates of letter identity and letter position are modulated by lexical frequency. Brain Lang. 125, 11–27 (2013).

Estes, W. K., Allmeyer, D. H. & Reder, S. M. Serial position functions for letter identification at brief and extended exposure durations. Percept. Psychophys. 19, 1–15 (1976).

Friedmann, N. & Gvion, A. Letter position dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 18, 673–696 (2001).

Perea, M. Orthographic neighbours are not all equal: Evidence using an identification technique. Lang. Cogn. Process 13, 77–90 (1998).

Johnson, R. L. & Eisler, M. E. The importance of the first and last letter in words during sentence reading. Acta Psychol. (Amst) 141, 336–351 (2012).

White, S. J., Johnson, R. L., Liversedge, S. P. & Rayner, K. Eye movements when reading transposed text: The importance of word-beginning letters. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 34, 1261–1276 (2008).

Tydgat, I. & Grainger, J. Serial position effects in the identification of letters, digits, and symbols. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 35, 480–498 (2009).

Perea, M. & Lupker, S. J. Can caniso activate casino? Transposed-letter similarity effects with nonadjacent letter positions. J. Mem. Lang. 51, 231–246 (2004).

Perea, M. & Fraga, I. Transposed-letter and laterality effects in lexical decision. Brain Lang. 97, 102–109 (2006).

Johnson, R. L. The flexibility of letter coding: Nonadjacent letter transposition effects in the parafovea. In Eye Movements (eds van Gompel, R. P. G. et al.) 425–440 (Elsevier, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044980-7/50021-5.

Perea, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Carreiras, M. Transposed-letter priming effects for close versus distant transpositions. Exp. Psychol. 55, 384–393 (2008).

Ktori, M., Kingma, B., Hannagan, T., Holcomb, P. J. & Grainger, J. On the time-course of adjacent and non-adjacent transposed-letter priming. J. Cogn. Psychol. 26, 491–505 (2014).

Perea, M., Mallouh, R. A. & Carreiras, M. The search for an input-coding scheme: Transposed-letter priming in Arabic. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 17, 375–380 (2010).

Velan, H. & Frost, R. Letter-transposition effects are not universal: The impact of transposing letters in Hebrew. J. Mem. Lang. 61, 285–302 (2009).

Lee, C. H. & Taft, M. Are onsets and codas important in processing letter position? A comparison of TL effects in English and Korean. J. Mem. Lang. 60, 530–542 (2009).

Lee, C. H. & Taft, M. Subsyllabic structure reflected in letter confusability effects in Korean word recognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 18, 129–134 (2011).

Rastle, K., Lally, C. & Lee, C. H. No flexibility in letter position coding in Korean. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 45, 458–473 (2019).

Lee, C. H. & Kim, J. Letter transposition effect in the Korean multi-syllabic word. J. Linguist. Sci. 86, 339–352 (2018).

Simpson, G. B. & Kang, H. Syllable processing in alphabetic Korean. Read Writ. 17, 137–151 (2004).

Lee, C. H., Kwon, Y., Kim, K. & Rastle, K. Syllable transposition effects in Korean word recognition. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 44, 309–315 (2015).

Kim, J., Lee, C. & Nam, K. Syllable transposition effect on processing the morphologically complex Korean noun Eojeol. Korean J. Cogn. Biol. Psychol. 30, 261–268 (2018).

Kim, J., Jung, J. & Nam, K. Neural correlates of confusability in recognition of morphologically complex Korean words. PLoS ONE 16, e0249111 (2021).

Kim, S., Paterson, K. B., Nam, K. & Lee, C. Lateralized displays reveal the perceptual locus of the syllable transposition effect in Korean. Neuropsychologia 199, 108907 (2024).

Taft, M., Zhu, X. & Peng, D. Positional specificity of radicals in Chinese character recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 40, 498–519 (1999).

Perea, M. & Pérez, E. Beyond alphabetic orthographies: The role of form and phonology in transposition effects in Katakana. Lang. Cogn. Process 24, 67–88 (2009).

Perea, M. & Carreiras, M. Do transposed-letter similarity effects occur at a syllable level?. Exp. Psychol. 53, 308–315 (2006).

Ratcliff, R. A theory of order relations in perceptual matching. Psychol. Rev. 88, 552–572 (1981).

Proctor, R. W. A unified theory for matching-task phenomena. Psychol. Rev. 88, 291–326 (1981).

Pelli, D. G. The Videotoolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 10, 437–442 (1997).

Brainard, D. H. The Psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10, 433–436 (1997).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Preprint at https://www.R-project.org (2025).

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J. & Bates, D. M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 59, 390–412 (2008).

Kim, S., Lee, C. & Nam, K. The examination of the visual-perceptual locus in hemispheric laterality of the word length effect using Korean visual word. Laterality 27, 485–512 (2022).

Rossion, B. et al. Hemispheric asymmetries for whole-based and part-based face processing in the human fusiform gyrus. J. Cogn. Neurosci 12, 793–802 (2000).

Ventura, P. et al. Hemispheric asymmetry in holistic processing of words. Laterality: Asymmetries Body Brain Cogn. 24, 98–112 (2019).

Kinoshita, S. & Norris, D. Transposed-letter priming of prelexical orthographic representations. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 1–18 (2009).

Lee, C. H., Lally, C. & Rastle, K. Masked transposition priming effects are observed in Korean in the same–different task. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 74, 1439–1450 (2021).

O’Regan, J. K. & Jacobs, A. M. Optimal viewing position effect in word recognition: A challenge to current theory. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 18, 185–197 (1992).

Marcet, A., Perea, M., Baciero, A. & Gomez, P. Can letter position encoding be modified by visual perceptual elements?. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 72, 1344–1353 (2019).

Perea, M., Marcet, A., Baciero, A. & Gómez, P. Reading about a relo-vution. Psychol. Res. 87, 1306–1321 (2023).

Dehaene, S., Cohen, L., Sigman, M. & Vinckier, F. The neural code for written words: A proposal. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 335–341 (2005).

Ziegler, J. C., Bertrand, D., Lété, B. & Grainger, J. Orthographic and phonological contributions to reading development: Tracking developmental trajectories using masked priming. Dev. Psychol. 50, 1026–1036 (2014).

Colombo, L., Sulpizio, S. & Peressotti, F. The developmental trend of transposed letters effects in masked priming. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 186, 117–130 (2019).

Pagán, A., Blythe, H. I. & Liversedge, S. P. The influence of children’s reading ability on initial letter position encoding during a reading-like task. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 47, 1186–1203 (2021).

Gomez, P., Marcet, A. & Perea, M. Are better young readers more likely to confuse their mother with their mohter?. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 74, 1542–1552 (2021).

Perea, M., Marcet, A. & Gómez, P. How do Scrabble players encode letter position during reading?. Psicothema 1, 7–12 (2016).

Gómez, P., Marcet, A., Rocabado, F. & Perea, M. Is letter position coding a unique skill for developing and adult readers in early word processing?. Evid. Masked Priming. Psychol. Res. 89, 93 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2022-NR075596 and RS-2023-00249539) and the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2022-NR070542).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the studies. SJJ was responsible for project supervision. YJJ and SJJ designed the experiments, and YJJ collected the data. All authors analyzed the data. SAY and SJJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, SA., Jeong, Y.J. & Joo, S.J. The flexible encoding of syllable positions in Korean Hangul. Sci Rep 15, 42987 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26940-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26940-y