Abstract

The production of waste marble is the ultimate concern of the construction industry’s recent success in satisfying the huge need for marble stones. This study predicts the compressive strength of waste marble powder concrete using machine learning methods XG Boost, AdaBoost, Cat-Boost, Gradient-Boosting, Light Gradient-Boosting, and decision tree. For this purpose, a comprehensive dataset was developed from previously published literature, incorporating input features such as cement, fine and coarse aggregates, superplasticizers, silica fume, marble dust, and water, with compressive strength (CS) as the output parameter. Based on the outcomes, XG Boost model outperforms other models to predict CS with R2 values of 0.999 and 0.915 on the train and test stage, respectively. The decision tree model also shows consistent performance with R2 > 0.85 for both train and testing phases. In addition, experimental assessment was also conducted to verify the outcomes of machine learning (ML) modeling and quantify the CS of concrete specimens having marble dust as binder replacement (5–20% by weight). In addition, feature importance analysis highlights that superplasticizers, cement, and silica fume were the most weighted factors that affected CS. According to partial dependency plot (PDP) analysis, combined data on concrete strength versus cement concentration shows that the strength of the material increases from 37.5 MPa to 57.5 MPa when the cement concentration increases from 300 kg/m3 to 500 kg/m3. Furthermore, microstructural evaluation revealed a dense and well-compacted matrix in concrete containing waste marble powder, with improved bonding between the binder and aggregates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete has emerged as the most preferred construction material for various infrastructures of the twenty-first century on account of its long service life, durability, ease of preparation and fabrication from easily available constituents1,2,3. To date, concrete is produced more than 10 billion tons every year, constituting almost as much as 1.5 tons per capita worldwide4,5. It takes 0.8 to 1.2 cubic meters of aggregates to produce one cubic meter of concrete. Aggregates occupy 70–80% of the total volume of concrete, of which 25–30% is occupied by fine aggregate6. The fine aggregate is a natural resource, and its excessive demand has led to a shortage of resources. On the contrary, waste generation is rising due to high production, construction and demolition activities in developing countries and has become a matter of grave concern7,8. Currently, this waste is being recycled either in the form of landfilling or disposed of9,10,11,12. This waste releases huge amounts of fine solid particles into the air, water and soil as pollutants during crushing, handling and disposal13,14,15,16,17.

Spain, Brazil, Algeria, Sweden, France, China, Turkey, India, Egypt, Iran, and Italy are the top producers of marble18. Nearly 10% of the world’s marble powder is mined in India, the third-largest producer of marble in the world19. Furthermore, nations like Pakistan, the US, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Portugal, Germany, France, Norway, and Greece are the main destinations for the import and processing of stone20. A significant amount of marble trash is produced at various phases of the stone mining and processing processes21. The finer marble dust created during sawing and cutting might have detrimental effects on one’s health. Additionally, the disposal of this marble dust may lead to poor soil quality and a decrease in the fertility of the corresponding area22,23,24,25,26. The production of marble stone accounts for over 30% of all marble waste27,28. According to the USGS, around 140 million tons of marble and granite were produced annually worldwide in 201429. According to the UNFC system, as of April 2015. 99.77% of the resources fell into the remaining resources category, with only 0.23% designated as reserved resources29. China is the world’s greatest producer of marble, with around 350 million square meters of marble planks29. Every year, around 7 lac tons of garbage are produced in Egypt’s Shaq Al-Thoban industrial and site regions30. According to Brundtland’s definition of sustainable development31, adding mineral admixtures and other waste materials has become increasingly important with the goal of lowering the use of natural resources while keeping the environment in mind32,33. At the national and international levels, alternative sustainable techniques should also be implemented to decrease the use of natural resources34,35,36. In contrast, recycled aggregates are typically utilized at the local level to stabilize road materials37. However, the manufacture of concrete has a significant carbon footprint, accounting for 8% of carbon dioxide emissions worldwide due to its widespread usage in several applications38,39,40. 7.8% of nitrogen oxide emissions, 4.8% of sulfur oxide emissions, 5.2% of particulate matter emissions smaller than 10 mm, and 6.4% of particulate matter emissions smaller than 2.5 microns are all attributable to the manufacturing of concrete worldwide38.

The use of environmentally favourable by-products is seen to be a successful tactic for lowering CO2 emissions with the goal of sustainable development25. For evaluating mechanical performance, Aliabdo, et al.27 discovered that a 10% replacement of waste marble powder with sand in addition to superplasticizing admixtures yielded the highest compressive strength compared to the reference mix. A study by Ghorbani, et al.41 found that 10% of waste marble powder to cement as a fine aggregate increased the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of the cubes. According to Alyousef, et al.42, the compressive strength of concrete was maximum with 15 wt% of MD as sustainable sand replacement up to 360 days of curing. They also reported that the compressive strength of cement mortar significantly improved with the increasing percentage of marble dust addition. Ergün43 also reported that the compressive strength increases when the marble dust is replaced with cement at 5.0% to 7.5%. Demirel44 reported that marble dust content replacement with sand up to 100% resulted in reduced porosity, while both UPV values for porosity and pulse velocity increased, in addition to water penetration and phosphate resistance. Binici, et al.45 was found that in comparison with other specimens, the test results revealed that the sulfate resistivity of the specimens, made with a replacement level of 15 per cent marble dust instead of sand, was the highest, had the least loss in compressive strength and were much more resistant to water penetration. In the work from Buyuksagis, et al.46 the addition of marble waste into cement-based adhesive mortar in 5 different amounts (20%, 40%, 60%, 80% and 100%). In the study carried out, after the seventh day, in the presence of marble powder, the compressive strength of the mortar mix increased slightly, but for the three and twenty-eight-day strength, it decreased. The replacement of dolomite with 80% marble dust for marble powder in tile adhesive resulted in a remarkable effect on the tensile value. This is attributed to the fact that marble powder is 2.7 g/cm3 denser than the density of bonding mortar. However, experimental assessment is not only time-consuming but also a costly procedure47,48. To minimize the procedure and accelerate the process, numerical modeling and analysis become popular in recent times49,50,51,52. Besides numerical modeling, approaches such as response surface modeling (RSM) and feature importance analysis have also showed significant performance to optimizing properties of concrete modified with supplementary cementitious materials53.

In recent years, AI has enabled ML and deep learning algorithms to be used to predict the mechanical properties of concrete as well54,55,56,57,58. Learning approaches such as regression, clustering, and classification may be utilized to predict distinct factors whose efficiencies differ59,60. They can also help to predict the concrete compressive strength precisely61,62. It has long been known that the performance of a number of characteristics can be predicted with machine learning algorithms63,64,65. Common prediction methods related to concrete mechanical properties include artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machines (SVM), decision trees (DT), gene expression programming (GEP), random forests (RF), and deep learning (DL)66,67. Barkhordari, et al.68 and Ashrafian, et al.69 determined that the optimum model for predicting the mechanical properties of concrete pavement is RF, outperforming M5 rule model tree. An ANN was created by Naderpour, et al.70 to forecast the compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC). Afzal, et al.71 utilized eleven algorithms to predict the shear strength of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Afzal, et al.72 used ANN with multi-objective grey wolves (MOGW) as an optimizer to predict the static properties of concrete containing silica fume. A machine learning system was also used by Veza, et al.73 to predict the durability of reinforced concrete structures. Bakır, et al.74 presented a machine learning-based autonomous fracture detector for concrete buildings. Al-kahtani, et al.75 have successfully predicted the strength of carbon nanotube cement materials with precision through RF methods. This prediction had a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.98. The authors further evaluated the CS of RBC-based methods based on boosting algorithmic strategies with GB, AdaBoost regressor and XGB. When comparing various techniques, they found out that XG-Boost was much more successful than others and R2 was larger than 0.90. GPR was able to predict the flexural strength to an extent of up to 90% and ANN was able to predict to an extent of up to 75% based on the previous study. The R2 values that RSM-based prediction models have reported for each correct response are higher than 0.8276. The best random forest regression (RFR) models, whose R2 values were above 0.93, were found to predict the mixing and compaction temperatures. The extreme gradient boosting (XGB) model was the most successful approach to shear viscosity prediction among those explored77. In the evaluation of the strength of 3D-printed concrete by Uysal and Sumer77 the performance of the LGB model was better as compared to the performance of the SVR model, XGB model, and RF model.

Although using marble dust in concrete is well explored in civil and environmental engineering domain but modelling and forecasting of CS is a new approach, and hence very few studies have been performed which include the use of marble dust as an alternate binder option and then validate the modeling approach using experimental evaluation. This paper attempts to fill the identified gap by using six different advanced machine learning models for marble dust-based concrete i.e. Ada-Boost, Gradient boost, XG-Boost, Light Gradient Boosting, Cat-Boosting and Decision Tree. For this study, the analysis was performed considering seven input parameters as they have been identified from the literature as the significant parameters influencing CS. Furthermore, the results of the machine-learning modelling were confirmed based on the experimental data that were obtained in this study. Furthermore, this study represented a novel attempt to implement SHAP and PDP methods to analyze the effects of the aforementioned inputs on the prediction of CS. Additionally, experimental assessments were also carried out to validate the outcomes of machine learning modeling.

Research significance

This study examines how machine learning can be used to predict the marble dust content in concrete’s compressive strength. The methodical laboratory process of casting specimens, curing them for a specified time, and analyzing them is still problematic from a stand time point of view. This innovative approach reduces waste and greenhouse gas emissions and creates a sustainable cement alternative concrete. To prevent the time and cost consumption issue, new machine learning algorithms are researched to predict the mechanical properties of waste concrete. Therefore, the objective of this research is to study marble dust concrete so that the waste of marble dust can be controlled and to assess the best machine learning method. The novelty and significance of the current work lie in conducting experiments on waste marble (powder-based) concrete (WMC) and developing a WMC prediction model using computational techniques. In addition, this work applies supervised machine learning methods to forecast and assess the compressive strength of WMC. The results of the experimental work are compared against machine learning algorithms.

Methodology

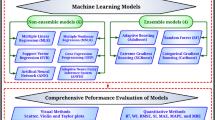

This study utilized both the experimental and machine learning based modeling to evaluate the mechanical performance of marble dust incorporated concrete. For experimental evaluation, the first step was to collect materials, development of mix design and the casting of concrete specimens. After that the next step was testing CS and microstructure of specimens after 7, 28 and 56 days of curing. Simultaneously, a dataset containing 440 data points was collected from previously published literature for conducting the machine learning modeling. To ensure the generalizability and validation of the ML models, the experimental data was used as the validation dataset in the GUI developed in this study. Figure 1 visualizes the process of whole machine learning modeling work.

Experimental setup

Materials and mix proportions

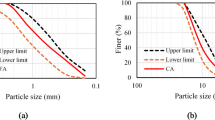

In this experiment, Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) served as the primary binding material. To enhance the concrete’s mechanical performance and durability, silica fume (SF), a fine pozzolanic byproduct of silicon and ferrosilicon alloy production, was incorporated. Additionally, marble dust (MD) was introduced as a partial cement replacement to assess its impact on strength development. Cement is replaced by marble dust at weight basis, 5%, 10%,15% and 20%. The aggregate consisted of fine aggregate (FA) in the form of well-graded natural sand and coarse aggregate (CA) comprising crushed stone with a maximum particle size of 19 mm. However, the physical and chemical properties of marble dust used in this study have been provided in Tables 1 and 2. Additionally, the particle size distribution of marble dust, fine and coarse aggregate has been illustrated in Fig. 2.

The concrete mixtures were prepared using potable water, ensuring proper hydration of the cementitious components without contamination. Furthermore, a superplasticizer was included to optimize the workability and improve overall performance. Table 3 presents the mix design of the concrete mixes.

Test setup and experimentations

The workability of the fresh concrete was evaluated by performing slump test following the standard ASTM C143/C143M78. For the experiment, compressive strength test was carried out following the code ASTM C3979. Here CS was measured using a testing setup that applied a uniaxial load until failure with a constant loading rate of 0.25 MPa/sec, as seen in Fig. 3(a). This ensured an accurate assessment of the mechanical performance of all the samples. Additionally, microstructural analysis was conducted using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which provided high-resolution imaging to examine surface morphology and material characteristics, as shown in Fig. 3(b). The SEM analysis was carried out based on the guidelines provided by ASTM C1723-16 standard80.

Dataset development

A database of compressive strength was constructed based on 500 test observations of marble dust concrete composites from the corresponding published literature using systematic literature review (SLR) approach. The target output variable was the 28-day compressive strength of the standard concrete. In compiling the dataset, only CS test results that adhered to the ASTM C3979 guidelines for cylindrical concrete specimens were considered to ensure consistency and reliability of the data. Articles that conduct CS test on cubic specimens were excluded from the collected data. While, some degree of variability in material properties across the sourced studies was inevitable, such variations were relatively minor, as only mixes with comparable ranges of binder (different types of OPC), aggregates (coarse aggregate size ranges between 8 and 20 mm), water, supplementary cementitious materials (containing silica fume and other SCMs having similar properties like silica fume), and waste marble dust (discarded marble dust that were processed and replaced as binder) contents were included. This controlled selection minimized the influence of atypical material properties on the dataset. Furthermore, experimental conditions including specimen sizes, and loading rates were restricted to those reported in accordance with ASTM guidelines, thereby reducing inconsistencies between individual studies.

Dataset preprocessing and statistical evaluation

After development of the dataset, the data were subjected to additional pre-processing to eliminate outliers and samples containing missing input values. The final dataset consisted of 440 test observations and seven input characteristics after this pre-processing stage. In this study, the dataset containing 440 mix combinations were randomly split into the training set and test set at the ratio of 80:20. This randomization to combine two sets ensures that each set represents the complete data distribution with the reduced selection bias. Furthermore, outlier removal and standardization were carried out on the training data alone. To ensure that the ML models are not biased by the scale of these features, appropriate normalization techniques were applied during model training to rescale the input features to a uniform range (between 0 and 1). This step is essential in preventing features with larger numerical values (FA and CA) from disproportionately influencing the learning process, especially in algorithms such as GB and DT, where split-based calculations can be affected by unscaled inputs. However, the splitting was performed before any model development to guarantee a non-bias assessment over the generalization of a model evaluated on unknown data.

Furthermore, the statistical assessment of the dataset was performed in Python by employing built-in data analysis libraries. The dataset was first imported into a pandas DataFrame, and then using the describe() function, the key statistical measures including maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation were automatically generated for each input and output feature. In addition, customized functions such as df.mean(), df.std(), df.min(), and df.max() were also used to cross-check and validate the results obtained from the descriptive summary. Table 4 evaluates the statistical parameters of the collected dataset.

Machine learning modelling

Machine learning (ML) is a field of artificial intelligence, broadly defined, that studies the ability of computers to learn from data and to understand complex patterns in the data without much programming. The ML models developed in this study had been built and implemented in the Jupyter notebook (v7.2.2) using Python programming language (v3.12.8). The Pandas and NumPy libraries were used for data preprocessing and statistical analyses. Model performance was assessed using Scikit-learn metrics. Graphs such as regression plots, residual analysis, SHAP, and PDP were also made using Matplotlib, Seaborn, and the SHAP library. All experiments were run in a well-segregated computational environment using Anaconda navigator to ensure reproducibility.

Extreme gradient boosting (XG Boost)

It’s a tree-based ensemble learning process according to the boosting code. Essentially, new learners are themselves sequentially fitted to the residuals of previous learners, and they are fit to predict the residuals from the previously learned model, thereby augmenting it. Extreme Gradient (XG) boosting is based on a decision tree with gradient boosting. Using well-known methods for feature importance, such as XGBoost, users can learn about the relative significance or contribution of input factors in response prediction, as single decision trees are very interpretable. Through this regularized model formulation, dubbed XGB, they can combat overfitting, even though it also utilizes a variety of tweaks to mitigate overfitting and more complicated issues81,82. In contrast, the XGB-founded approach is the best predictor for conventional concrete compressive strength. XGB generates its final prediction for a continuous target variable—such as compressive strength (CS)—by aggregating the outputs of multiple decision trees. This process is guided by an objective function F which integrates both a loss function and a regularization component, as represented in Eq. (1):

where, \(\:l\left({y}_{i},{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{i}\right)\) quantifies the error between the predicted value \(\:{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{i}\) and true target \(\:{y}_{i}\). \(\:\cap\:\left({f}_{k}\right)\) denotes the regularization term applied to each tree \(\:{f}_{k}\), to control model complexity and reduce the risk of overfitting. The cumulative prediction for a given input \(\:{x}_{i}\), is computed by summing the contributions of all K trees, as shown in Eq. (2):

Adaptive boosting

Adaptive Boosting (AB) trains weak learners on the first training data and modifies the training data distribution according to the predicted performance for the next data set K. It is important to note that training specimens that are poorly predicted in the previous stage will be given greater responsibility for prediction accuracy in the next step. The aggregation of weak learners with different weights83 results in powerful learners. The weak classifier is constructed first by training on the training examples. Next, the faulty models are combined with the untrained samples to create a new training specimen. This sample is also used to learn the second weak classifier. The combined data uses the wrong specimen combined with unconditioned models to create a new training specimen that can be used to train the new third weak classifier. This approach resulted in a revised robust classifier that we eventually obtained. Ada boost gives different weights to the specimens to increase the number of accurate classifications. It is assumed that the best predictions of a final output from the model are correct enough to be reliable.

The above equation quantifies the maximum deviation between predicted and actual values across all observations, representing the worst-case prediction error. In this context, Yi denotes the result variable value and Xi represents the corresponding input feature vector. Therefore, the total error ratio ek of this step can be computed as:

Meanwhile, the weight wk=1, i of individual data for the next step train update:

Here, ak is the weight of the weak learner, where k = 1, …, N. νϵ(0,1) is a regularization term that helps avoid overfitting problems.

Gradient boosting (GB)

The Gradient Boosting (GB) tree is a stage-wise additive model which essentially provides information by minimizing the prediction value for any given loss function. More trees in the model may correspond to a perfect model, but as the fitting of the model to the training data approaches, it could be relevant to simplify the model. The advantage of GB lies in the fact that it doesn’t overfit and utilizes smaller computations instead of a function of the objective. One widely used method of enhancing the output performance from a tree-based learning method is working through “boosting”. Furthermore, the importance of GB may be changeable. GB progresses the basis function so that adding a basis function continues to minimize the selected error function84. In the first place, advantages should be established upon the preferable loss function that could be divided; therefore, all the steps could be associated based on the detraction of this loss function85. Equation (7) represents the output of a Gradient Boosting (GB) model, which aggregates the predictions of multiple decision trees to form a robust predictive ensemble. In this expression x is a data point, N is the total number of decision trees involved in the ensemble, fi(x) is the prediction made by a single decision tree with index I, and \(\:\widehat{y}=f\left(x\right)\), is computed by summing the individual outputs of all trees:

Equation (8) defines the loss function L, which the gradient boosting algorithm seeks to minimize throughout the training process. Here, d is a function that quantifies the discrepancy between the actual target value \(\:{y}_{k}\), while n represents the number of training samples used during each boosting iteration.

Light gradient boosting

LGB modelling is a kind of gradient boosting that uses learning tree-based algorithms. This approach yields a speed value for the process of training the light gradient boosting modelling, thereby increasing the effectiveness86. Regarding XG boost, the unique aspect of light gradient boosting modelling is that it uses histogram-based techniques. Hence, it might reduce memory usage and allow faster training. As a DT is the basis of light gradient boosting, dissection accuracy is not an integral part. The brute-force regularization method is applied to overfitting if required. In comparison to standard DT formats, there are multiple enhanced elements of light gradient-based modelling. One example is that in DT, the carious run is often performed with the typical level-wise growth strategy that is no longer effective, leading to higher memory usage. Nevertheless, leaf-wise development LGB is an evident alleviate with a relative segment length87. In LightGBM (LGB), Information Gain (IG) serves as a critical criterion for constructing decision trees, guiding the selection of the most informative feature to split at each node. The IG for a given feature with respect to a dataset is defined in Eq. (9):

In this expression, C denotes the complete dataset (or a specific subset), and \(\:{F}_{n}\:\left(C\right)\:\)represents the entropy of the dataset prior to the split. The subset \(\:{C}_{v}\:\) contains all data instances for which feature A assumes the value v, with \(\:\left|{C}_{v}\right|\) indicating the number of instances in that subset. \(\:{F}_{n}\:\left({C}_{v}\right)\) is the entropy of the subset after splitting.

The entropy, which quantifies the impurity or uncertainty within a dataset, is calculated as follows:

where, \(\:{p}_{b}\) represents the probability (or proportion) of instances belonging to class within dataset , and is the total number of distinct classes. Entropy helps evaluate the effectiveness of splits, with lower post-split entropy indicating higher purity and thus greater information gain.

Cat-Boost

CB is a tree-based gradient-boosting method with several characteristics that are target-specific. Key features of this action mechanism are its order-boosting method, which does not depend on shift prediction and the original elements. A category feature is a feature that has a unique set of values that are not always comparable to one another. It offers a range of features and category solutions. Its approach uses and optimizes tree splitting rather than pre-processing to help reduce overfitting88. CB is a variant of gradient boosting, which overcomes overfitting through ordered boosting and symmetric trees, demonstrating fast performance and parallel processing89. The Cat-Boost loss function is iteratively optimized and often has to be minimized according to a formula of the form:

where L is the total loss, wi represents weights ℓis the loss function, yi is the true label and f(xi) is the predicted value.

Decision tree

In order for a Decision Tree (DT), which is another supervised learning approach that is commonly utilized to classify problems, regression issues are usually classified, as shown in Fig. 4. The tree has categories within it. However, without a class, potential outcomes using self-regulating variables can be predicted with the regression method. A DT is a ranked classifier whose major knowledge of the database attributes can be arranged in the internal nodes. The outcomes are described on each leaf node, and the branch signifies the conclusion. DT consists of two types of nodes; decision node and leaf node. Leaf nodes do not branch further and examine the outcome of the decision and are considered decision nodes that have several classes and can follow any category. It is called because it is tree-related, where it starts with the root node and grows90. Figure 4 highlighted the schematic diagram of DT algorithm.

A Decision Tree (DT) partitions data into progressively smaller subsets using a hierarchical, tree-like framework. This structure comprises three primary node types: the root node (RN), which represents the initial point of data division; the decision nodes (DN), where conditional checks are applied to determine further branching based on specific feature values; and the leaf nodes (LN), which denote the final outcomes or class predictions. To assess the purity or disorder within the dataset, DT algorithms utilize entropy-based measures. The overall entropy of a dataset D is given by Eq. (12):

where Pk indicates the proportion of instances in D that belong to class k.

Here, T is the target variable, X is the attribute used for the split, c denotes each distinct value of attribute X, P(c) is the probability of observing value c, and E(c) represents the entropy of the subset corresponding to c. This formulation helps determine the optimal split by identifying features that most effectively reduce uncertainty.

Hyperparameter optimization of ML models

Optimization of ML model hyperparameters is a critical step to enhance predictive accuracy and generalization capability. For ensuring the balanced performance, this study systematically tuned key parameters for all models within a defined range using grid search method. This optimization process helps to minimize errors on unseen data and avoid overfitting or underfitting. Additionally, this process ensures that the trained models achieve optimal performance in terms of prediction accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency. The key hyperparameters along with their optimized value for all models has been shown in Table 5.

Performance evaluation

The models that were developed using different methods were evaluated using statistical data like the coefficient of determination (R2), MSE, RMSE, MAE and MAPE. But when the testing and validation of models may differ only slightly, estimating for new machine learning models remains essential to understand them in their entirety. Regression coefficients were calculated at the 95% confidence level. For the best fit, the RMSE value obtained from the equation should be as close to zero as possible. The derived formula for all the performance indicators used in this study is shown in Eqs. 14–17.

Parametric modeling

SHapley additive explanations (SHAP)

In recent years, machine learning models have influenced the SHAP approach. All SHAP are shown in each data sample as a dot. Thus, the colour of the dot corresponds to the value of that feature for each matching sample. In this study, the X location of the dots in the SHAP summary graphs demonstrates how much each attribute influences the model output. Thus, the summary plot has the most impactful features on the left side and the least impactful on the right. Also, the further a dot is to the right or left of 0, the more that attribute influences the model’s output. The red-tinged features show high input values and blue-toned features represent low input values. SHAP values describe how predictions would have been made if a feature was available for modelling and when it is not, making it capable of also being considerate of the horizontal functionality of a sample. They are given below and can be calculated from Eqs. (19) and (20).

Here g is the local explanation function. The outputs of x can only take value in 0, 1. The X initial numbers M of characteristics represent the explanation function, where i indicates the co-efficient for each of the linear combinations and then M represents the mapping function h that links those characteristics’ reduced inputs to their real input values so that x = h(x), therefore determining i according to (20). f is the prediction model, S is the subset of F that excludes the feature that needs to be predicted, and F is the set of all the input features. The value of the calculation, C, is noted down.

Partial dependence plot analysis (PDP)

In a machine-learning approach, the plot is known as a partial dependency plot (PDP), which averages the effect of the other characteristics in the data set to evaluate the relationship between a feature and the expected outcome. PDPs are used to interpret non-linear models because they show the graphic of one or two variables’ average effect on the expected outcome. It allows for easier human interpretation of non-linear correlations in the data. This means that PDPs can be used to explain the effect of water content, e.g., aggregate or additives on compressive strength, which makes sense in common materials science use cases where one would want to recommend the most favourable characteristics of concrete. Such insights help us improve the predictive model by showing how the outcomes are associated with some of the features of interest, which improve the interpretability and practicality of the model91. PDP is concerned with fixing an arbitrary value of each of the predictor variables and averaging the responses of the model on the data. This is done by averaging predicted responses over all observations in the dataset, keeping all other predictor variables constant.

Results and discussion

Experimental evolution of fresh and mechanical properties

The workability of the fresh concrete was evaluated by performing slump test. As seen in Fig. 5(a), there’s a gradual increase in workability with marble dust incorporation up to 10%. The outcomes highlighted that, 10% MD and 5% SF combination showed maximum slump of 118 mm. Beyond this level, the slump decreased progressively, with the lowest value of 83 mm recorded at 20% MD replacement. The outcomes confirm that marble dust up to 10% enhances particle packing and paste fluidity, while higher levels increase water demand and reduce workability. Furthermore, the mechanical test results presented in Table 6 illustrate the compressive strength values at different curing ages for various concrete mixes incorporating waste marble powder. The control mix along with all specimens containing marble dust exhibited a gradual increase in CS over time. In contrast, the modified mixes showed variations in strength depending on the percentage of marble powder used. The S5MD10 mix exhibited the highest compressive strength among all modified samples, reaching 37.22 MPa at 7 days and 51.65 MPa at 56 days, indicating an optimal replacement level. However, the S5MD20 mix displayed a reduction in strength compared to other modified samples, with CS values lower than the S5MD10 and S5MD5 mixes, suggesting that excessive marble powder negatively impacted strength due to increased porosity and reduced cementitious material availability. The statistical indicators, including standard deviation (St. Dev.), coefficient of variation (CoV), and confidence intervals (CI), confirm the reliability of the measured values, with lower CoV values indicating consistency in the results. Furthermore, the lower bound (LB) and upper bound (UB) also define the ranges of CS considering the 95% CI of the experimental results.

Figure 5 (b) and (c) further visualizes the compressive strength trends across different curing ages and the percentage changes in CS. As can be seen in Fig. 5(b), all mixes exhibited strength enhancement over time, with the most significant gains observed between 7 and 28 days due to ongoing hydration and pozzolanic reactions. The percentage change in CS, illustrated in Fig. 5(c), highlights that moderate levels of marble powder replacement (5–10%) enhanced strength, while excessive replacement (15–20%) led to a decline. This trend can be attributed to the dual role of marble powder: at optimal levels, it acts as a micro-filler, refining the pore structure and enhancing matrix densification, whereas at higher dosages, it increases the water demand and weakens the bond between the aggregates and binder, leading to strength reduction.

Data distribution and relationship between variables

Figure 6 depicts the correlation heatmap between various concrete mix components and compressive strength. Another big contributor to strength development is cement, which has a relatively low positive correlation of 0.37 with compressive strength. It also correlates positively with silica fume 0.16 and superplasticizer 0.41. The latter shows an important influence. All variables are measured in such ways that a positive correlation would mean the more of the variable, the larger the compressive strength, and a negative correlation would be the opposite of this. For example, the negative association of −0.26 between compressive strength and marble dust indicates that a higher concentration of marble dust means a lower compressive strength. The unfavourable relationship of fine to coarse aggregates is more pronounced with fine aggregate with contrary relations of − 0.22 fine aggregate and 0.17 coarse aggregate, respectively. The negative correlation of −0.26 for the water is indicative of how strength is usually reduced by the water content. According to the notable negative correlation of −0.58 between these two variables, fewer fine particles in the mix naturally means more coarse particles, and an inverse ratio is possible in a 3D inverse distribution.

The distribution plots of Fig. 7 reveal the variability and characteristics of key features in the dataset. Cement content is predominantly between 400 and 500 kg/m3, peaking around 450 kg/m3, reflecting typical usage in high-performance concrete, while silica fume and marble dust exhibit right-skewed distributions, with most values below 50 kg/m3 and 200 kg/m3, respectively, indicating their supplementary roles. Fine aggregate shows a bell-shaped curve, concentrated around 800–1000 kg/m3, while coarse aggregate displays a bimodal distribution with peaks at 800 kg/m3 and 1200 kg/m3, suggesting two distinct mix designs. Water content is centered around 180–200 kg/m3 with a slight skew, reflecting adjustments for workability and strength, and superplasticizer values are heavily skewed, with most below 5 kg/m3, highlighting its selective use for enhancing workability. Compressive strength is primarily distributed between 40 and 80 MPa, peaking around 60 MPa, representing mid- to high-strength applications, with a few samples exceeding 80 MPa for high-performance mixes. Overall, the dataset demonstrates controlled experimental designs with occasional deviations to explore unconventional proportions and achieve targeted concrete properties.

The scatter plots in Fig. 8 illustrate the relationship between compressive strength (MPa) and various mixed components. Cement content shows a generally positive relationship with compressive strength, with strength increasing as cement content rises, but this effect diminishes at higher levels, highlighting a saturation point. Silica fume exhibits a scattered and non-linear effect on strength, indicating variability and dependency on mix design. Marble dust displays a weak relationship, suggesting it primarily acts as a filler with minimal impact on strength. For fine aggregate and coarse aggregate, the plots show inconsistent and weak relationships with compressive strength, reflecting their structural roles rather than a direct influence on hydration or bonding. Water content, however, shows an inverse relationship, confirming that higher water levels reduce compressive strength by increasing porosity, while optimized levels improve strength. Superplasticizer demonstrates a clear positive correlation at lower dosages, enhancing strength by reducing water demand and improving workability, though this effect plateaus at higher contents. Overall, the relationships suggest that binders, water content, and chemical admixtures have the most significant influence on compressive strength, whereas aggregates and marble dust play supporting roles.

Outcomes of ML modeling

Predicted and actual compressive strength (CS) values for six ML models AdaBoost, XG Boost, Gradient Boosting, Cat Boost, Light GBM, and Decision Tree are regressed in Fig. 9. AdaBoost model with R2 values of 0.813 and 0.749 for training data and test data, respectively, is performing very well in prediction. A significant decrease in the R2 value of the test set signals underfitting, with the model failing to capture intricate patterns in the data, as seen by several points falling outside the 10% error margin. With very good R2 values of 0.999 (train) and 0.915 (test), nonetheless, the XG Boost model performs better, indicating good generalization to the test data and very good fitting to the train data. The majority of the data points fall within the 10% error margin and are very close to the X = Y line, demonstrating the model’s credibility in CS prediction. R2 values of the test and training data sets are 0.966 and 0.901, respectively, indicating the excellent performance of the Gradient Boosting model. This closeness proves that there is little or no overfitting and that the model accurately reflects the relationship between attributes and compressive strength. With R2 values of 0.999 (train) and 0.942 (test), the Cat Boost model also fares exceedingly well, with very good predicted accuracy and the least deviation from the experimental data. The Cat Boost plot shows the model’s superior handling of categorical data and robustness, with points tightly packed around the optimum prediction line.

Furthermore, considerably worse performance is obtained by the AdaBoost model on the test set (R2 = 0.749), even though it fits the training data well (R2 = 0.813). The dispersed test data points beyond the 10% error rate are a sign of overfitting, an occurrence where the model commits to memory the training data yet doesn’t generalize on new data. Comparing the overall outcomes, XGB achieved the highest R2 on train stage, which were about 3.3% higher than LGB and GBR, and 0.4% higher than CatB. Conversely, ADB recorded the lowest train R2, which was about 18.6% lower than LGB and GBR as well as nearly 18.6% lower than CatB. Similarly, on the test set, CatB demonstrated the best prediction which was about 2.9% higher than XGB and 3.1% higher than LGB. Compared to GBR and DT (0.850), CatB’s performance was 4.5% and 10.8% higher, respectively. Meanwhile, ADB yielded the lowest R2, which was about 16.2% lower than CatB and 8.8% lower than DT.

Furthermore, ML models were evaluated based on the distribution of their prediction errors, as shown in Fig. 10. Gradient Boosting produced stable predictions with residuals mostly confined within ± 5 MPa. AdaBoost showed the largest variability, with residuals ranging from − 10 MPa to + 12 MPa, which is about 140% wider than Gradient Boosting and indicative of underfitting. CatBoost demonstrated the best performance by maintaining residuals within ± 3 MPa, which is about 40% narrower than Gradient Boosting and nearly 75% narrower than AdaBoost. Furthermore, XGBoost contained residuals within ± 4 MPa, about 20% narrower than Gradient Boosting and substantially smaller than AdaBoost. LightGBM showed a reasonable spread of −4 MPa to + 5 MPa, only slightly wider than XGBoost. By contrast, the Decision Tree model had minimal residuals in training but exhibited the widest test spread of ± 15 MPa, which is 200% larger than Gradient Boosting and five times wider than CatBoost, highlighting severe overfitting. Considering the performance of all models, CatBoost achieved the narrowest error range, followed by XGBoost and LightGBM, while AdaBoost and Decision Tree demonstrated poor error control.

SHAP analysis results

The bar charts in Fig. 11 highlights that superplasticizer (SP) is the most influential feature in predicting compressive strength, with the highest mean SHAP value of + 6.11 based on DT model, emphasizing its critical role in enhancing workability and strength. Cement follows as the second most impactful feature based on five ML models (except CatB), given its primary role as a binder in forming a dense concrete matrix. Following cement, water and silica fume showed the significance to predict the model’s outcome. Pozzolanic materials like silica fume (+ 3.34) significantly improve strength by filling voids and enhancing hydration, while water (+ 3.00) has a moderate impact, balancing hydration and porosity. Fine aggregate and coarse aggregate contribute less directly to strength, acting mainly as structural elements. Marble dust, with the lowest SHAP value (+ 0.73 based on CatB model), serves a minimal role, primarily as a supplementary filler material. Based on the analysis, the results revealed that most of the ML models exhibited a consistent trend in the feature importance rankings of the selected input materials for predicting compressive strength.

Furthermore, in Fig. 12 the SHAP summary plots show that the superplasticizer has the highest positive impact on predictions, with SHAP values increasing up to + 15 (based on DT model) at higher feature values, indicating its dominant role in enhancing the concrete matrix. As can be seen, all ML models except CatB visualized that cement exhibits the second highest strong positive influence, with high SHAP values at greater proportions, confirming its significance in densifying and strengthening concrete. Silica fume contributes positively at higher feature values due to its pozzolanic activity, while water shows mixed effects, with higher levels reducing strength due to increased porosity. Fine aggregate displays fluctuating SHAP values, reflecting variable effects based on its proportion, while coarse aggregate shows minimal impact. Marble dust has negligible SHAP variation, affirming its minor role in all the model’s predictions.

Overall, the SHAP analysis underscores the importance of optimizing SP, cement, and silica fume proportions to achieve higher compressive strength, while carefully balancing water content to prevent porosity. Aggregates play a supporting role in ensuring matrix stability, but their direct impact on compressive strength is minimal compared to the primary binders and admixtures. This analysis provides actionable insights for mixed design, highlighting the features that significantly influence strength and those with supplementary effects. Al-kahtani, et al.75 stated that the feature interaction plot and the RHA-cement content had a prevailing positive effect on the CS of RBC. Karim, et al.92 explains that the SHAP value (magnitude) of the age feature is negative for the first 70 appearances and is excellent positive for the rest of the sample (71–140). Whereas, in the other direction, a higher SHAP value in the plot first taken as calibration indicates that the coarse aggregate feature outperforms 20–115 cases. As per SHAP studies that were done by Karim, et al.92 curing time has the greatest effect on the predicted compressive strength of UHPC, followed by fiber, cement, silica fume, and super-plasticizer. Unlike the fly ash parameter, its parameter has no effect on UHPC compressive strength.

PDP analysis

Figure 13 shows partial dependence graphs that show how the different aspects of the concrete mix influence the strength of the concrete mix. Concrete Strength vs. Cement Concentration combined data shows that the strength of the material increases from 37.5 MPa to 57.5 MPa when the cement concentration increases from 300 kg/m3 to 500 kg/m3. This means that cement has an extraordinarily positive correlation with strength. Silica fume and superplasticizer are two examples of materials that can be used to achieve huge increases in strength. The incorporation of silica fume further improves compressive strength above 48 MPa with a dose of 20 kg/m3 while the incorporation of superplasticizer increases compressive strength to above 52 MPa with a low dose of (1–2 kg/m3). Conversely, strength decreases with higher water content, peaking at 140 kg/m3 before dipping to 42.5 MPa at 160 kg/m3. Both marble dust and fine aggregate show a very slight or no positive effect and the latter reduces strength from 48 MPa to 43 when this fine aggregate is increased. The effect of coarse aggregate is complex and only slight differences are found in the strength of the material. The relationships show that the optimum mixture is a large quantity of cement to a low quantity of water. The concrete strength is attributed to the addition of additives like silica fume and superplasticizer, but too much fine aggregate and water result in the concrete becoming weaker.

Based on Al-kahtani, et al.75 A cumulative 65% increase in the strength was within the range of 25–175 kg/m3, within the optimal constituency mix design validated by the PDP study. In another study, age was found to have a positive effect on the CS of RHA-FA concrete, showing a linear correlation between the two. The CS also increased with longer curing periods. Additionally, CS measurement showed an increment of approximately 12% when increasing the cement content from 350 to 600 kg/m3, ranging between 28.5 and 32 MPa. However, for the RHA content, it had an average CS reduction of 8.33% in value from 30 MPa to 27.5 MPa up to 170 kg/m3 in the 28.5–30 MPa range at the highest content of 350 kg/m3 mix. For fly ash (FA), the global CS value did not change. Water increased the Strength from 190 kg/m3 to 320 kg/m3. For the range of coarse aggregate densities of 1200 to 2000 kg/m3, CS values also declined from 36 MPa to 26 MPa. Hence, the density rises to ≈ 1200 kg/m3. The contribution of fine aggregate to strength was significant, ranging from 700 to 1500 kg/m3.

Microstructural evaluation

Figure 14 presents the SEM micrographs, providing a detailed examination of the morphological characteristics of marble dust and the specimen incorporating marble dust. As can be seen in Fig. 14(a), the surface topology of the cluster of marble particles, exhibiting an irregular shape with a highly porous and rough texture. The presence of fine-grained structures and loosely adhered particles indicates the potential for improved mechanical interlocking. Additionally, the porous nature of these particles provides a higher surface area, which can enhance pozzolanic reactivity and improve the interfacial bond with the cement matrix. Furthermore, Fig. 14(b) depicts the microstructure of a hardened concrete specimen containing 10% marble dust as a partial cement replacement. The SEM image reveals a significantly refined and compact microstructure, with marble dust particles appearing well-dispersed within the matrix. The formation of hydration products, including C-S-H gel, is evident, suggesting active participation of marble dust in the hydration process. Furthermore, the image indicates reduced porosity and enhanced particle packing density, which contribute to increased mechanical strength. The presence of well-integrated microstructural components confirms that the addition of MD leads to matrix densification, thereby reducing voids and refining the pore structures.

Discussion and comparison of the performance of ML models

Table 7 presents a comparative evaluation of machine learning models using R2, RMSE, MSE, MAE, and MAPE, visually depicting their predictive performance across training and testing datasets. The R2 values in Table 7 confirm that XG-Boost achieves the highest accuracy, with 0.999 during training and 0.915 during testing, indicating its ability to model complex patterns effectively while maintaining stability in testing. Additionally, the test R2 of XGBoost is only 3% lower than CatBoost and 0.1% higher than LightGBM. Gradient Boosting maintains a balanced performance, with an R2 of 0.966 (train) and 0.901 (test), making it a competitive alternative. However, the Decision Tree exhibits significant overfitting, as its R2 drops from 0.999 in training to 0.85 in testing, confirming its inability to generalize well. AdaBoost shows the weakest efficiency, with test R2 values almost 21% lower than CatBoost and 8% lower than Decision Tree.

Furthermore, XG-Boost records the lowest RMSE values in both training (0.0748) and testing (4.0186), reinforcing its precision and stability. CatBoost follows closely, achieving a test RMSE about 18% lower than XGBoost and 52% lower than AdaBoost, confirming strong predictive reliability. Gradient Boosting shows slightly higher errors but remains a stable alternative. However, the Decision Tree displays an extreme RMSE shift, from 0.0071 in training to 5.3314 in testing, highlighting overfitting. AdaBoost records the poorest performance, with a test RMSE about 71% higher than CatBoost and a MAPE nearly three times larger than Gradient Boosting, highlighting its limited predictive capability. The comparison between ML models tabulated in Table 7 establishes that XG Boost is the most effective model, followed by Cat Boost and Light GBM, while Decision Tree and AdaBoost exhibit significant weaknesses in predictive reliability and generalization. Additionally, Table 8 discusses the effectiveness of different ML models that were used in previous studies of concrete containing similar SCMs.

Practical implications and graphical user interface (GUI)

The outcomes of this study have significant practical implications for civil engineers, concrete technologists, and construction professionals. As the study establishes the predictive relationships between material composition and compressive strength by using advanced machine learning models, the results enable more efficient, and cost-effective concrete mix design without any laboratory-based trials. Additionally, it promotes the use of industrial waste such as marble dust as a SCM, which contributes sustainable construction practices by reducing environmental pollution and conserving natural resources. In the context of waste material management, marble processing industries can join hands with construction sectors to recycle marble dust waste to be used in part of the concrete production process. This will also reduce land filled impacts and avoid pollution. These findings of this study directly support field engineers in making quick, informed decisions regarding optimal material proportions and replacement strategies that ensure both environmental and structural performance.

Furthermore, to translate these advanced predictive capabilities into accessible engineering tools, a GUI has been developed using Python’s Tkinter framework. As seen in Fig. 15, this GUI allows users to input specific material quantities and instantly obtain predicted compressive strength values using the best-performing ML models. Additionally, it provides real-time performance metrics (R2, RMSE, MAE, MAPE) which makes it a powerful decision-support tool for engineers. The GUI developed in this study will help to bridge the gap between computational research and practical field application, and empower practitioners to design optimized, waste-incorporated concrete mixes on-site without the need for advanced coding or statistical expertise.

To further evaluate the performance of the GUI developed in this study, experimental mix proportions were given as input in the system and the outcomes of all the ML models were compared with the experimental 28days CS test results. Table 9 highlighted the predicted outcomes for the experimental mix ID SF5MD10 with all the performance metrics.

Limitations and future studies

Although the results of this study highlight the superior performance of XGBoost and Catboost algorithms in predicting the CS of marble dust modified concrete, it is important to recognize potential limitations of the employed models. These ensemble-based algorithms will perform poorly when exposed to input data that deviate significantly from the training distribution. For this study, if there’s high variability in material properties or mix proportions then the algorithms will show significant overfitting and poor predictions. In addition, their predictive accuracy can also diminish when extrapolating beyond the studied parameter ranges, as tree-based ensemble methods are inherently constrained to the domain of observed data. Moreover, sensitivity to noise or imbalance in the dataset could lead to biased or unstable predictions. Therefore, proper tuning and optimization must be done when applying these algorithms to scenarios involving untested ranges or significantly different material characteristics.

Future studies should focus on expanding the dataset with standardized and large-scale experimental investigations and exploring the durability performance of marble dust concrete. In addition, important parameters such as curing age, material’s physical and chemical properties should also be added to predict the CS of marble dust modified concrete. In addition, hybrid algorithms and deep learning-based modeling can also be applied to mitigate the potential overfitting issues and the prediction errors detected in this study.

Conclusions

The building industry is specifically interested in marble stone waste products. Thus, using marble waste powder in concrete composite at the time of construction may serve as an eco-friendly building material and a good effort to improve the environment. However, the most significant findings of this study are:

-

Experimental evaluation highlighted that an optimal replacement of 10% MD can achieve the maximum compressive strength of 48.17 MPa at 28 days. Further replacement of MD will cause a gradual reduction of CS.

-

Six machine learning models (XGB, ADB, GBR, LGB, CatB, and DT have demonstrated high functionality with excellent generalization and predictive power. Each of the models has an R2 value of more than 0.70.

-

The model exhibited its best performance with an R2 of 0.999 (0.915), an RMSE of 0.0074 (4.018), an MSE of 0.0056 (16.14), a MAE of 0.047 (2.03), and a MAPE of 0.121 (5.72), for training (testing), respectively.

-

The SHAP analysis revealed that the most influential factors on the predicted CS of concrete were superplasticizers, cement, and silica fume. Interactions between superplasticizers and cement content are the most favourably influencing factors for the compressive strength of the concrete.

-

According to PDP analysis, concrete strength versus cement concentration combined data shows that the strength of the material increases from 37.5 MPa to 57.5 MPa when the cement concentration increases from 300 kg/m3 to 500 kg/m3. The concrete strength is attributed to the addition of additives like silica fume and superplasticizer, but too much fine aggregate and water result in the concrete becoming weaker.

-

The microstructural assessment verified that MD helps to refine pore structures, fill micropores and help to pack the density which causes enhancement of concrete strength. However, excessive MD substitution will demand for additional water, which will reduce the strength of concrete.

The methodology, established in this study, has significantly reduced the number of laboratory tests and also saved considerable effort and time in predicting the compressive strength of concrete with the use of multiple input parameters. By running these algorithms on construction sites, engineers could speed up these processes and reduce the reliance on traditional testing methods.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to maintain control over unsupervised usage that may lead to unintentional duplication of research efforts or reduced novelty in future studies but the dataset are available from the corresponding author Dr. Md. Habibur Rahman Sobuz (email: habib@becm.kuet.ac.bd) on reasonable request.

References

Askari, D. F. A., Shkur, S. S., Rafiq, S. K., Hilmi, H. D. M. & Ahmad, S. A. Prediction model of compressive strength for eco-friendly palm oil clinker light weight concrete: a review and data analysis. Discover Civil Eng. 1 (1), 140 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Three-dimensional concrete printing technology from a rheology perspective: a review. Adv. Cem. Res. 36 (12), 567–586 (2024).

Yao, Y., Zhou, L., Huang, H., Chen, Z. & Ye, Y. Cyclic performance of novel composite beam-to-column connections with reduced beam section fuse elements, Structures, vol. 50, pp. 842–858, 2023/04/01/ 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.02.054

Kanojia, A. & Jain, S. K. Performance of coconut shell as coarse aggregate in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 140, 150–156 (2017).

Zhang, W., Lin, J., Huang, Y., Lin, B. & Liu, X. State of the Art regarding interface bond behavior between FRP and concrete based on cohesive zone model. Structures. 74, 108528 (2025).

Chen, D. et al. A state of review on manufacturing and effectiveness of ultra-high-performance fiber reinforced concrete for long-term integrity of concrete structures. Adv. Concrete Constr. 17 (5), 293–310 (2024).

Aayaz, R. et al. Evaluating mechanical and environmental impacts of sustainable natural fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete incorporating supervised machine learning methods. Case Stud. Constr. Materials, 23. e05154, (2025).

Dai, T. et al. Waste glass powder as a high temperature stabilizer in blended oil well cement pastes: Hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties. Construction Building Materials, 439, 137359, 2024/08/16/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137359

Sobuz, M. H. R. et al. Combined influence of crushed brick powder and recycled concrete aggregate on the Mechanical, durability and microstructural properties of Eco-Concrete: an experimental and machine Learning-Based evaluation. Journal Mater. Res. Technology, 76, 8757–8776 (2025).

Hossain, M. A., Datta, S. D., Akid, A. S. M., Sobuz, M. H. R. & Islam, M. S. Exploring the synergistic effect of fly ash and jute fiber on the fresh, mechanical and non-destructive characteristics of sustainable concrete, Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 11, p. e21708, 2023/11/01/ 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21708

Saha, A., Tonmoy, T. M., Sobuz, M. H. R., Aditto, F. S. & Mansour, W. Assessment of mechanical, durability and microstructural performance of sulphate-resisting cement concrete over Portland cement in the presence of salinity. Construction Building Materials, 420, p. 135527, 2024/03/22/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135527

Hasan, N. M. S. et al. Integration of Rice Husk Ash as Supplementary Cementitious Material in the Production of Sustainable High-Strength Concrete, Materials, vol. 15, no. 22, p. 8171, [Online]. (2022). Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/22/8171

Zhu, J., Wang, Z., Tao, Y., Ju, L. & Yang, H. Macro–micro investigation on stabilization sludge as subgrade filler by the ternary blending of steel slag and fly Ash and calcium carbide residue. J. Clean. Prod. 447, 141496 (2024).

Zhang, S., Tan, D., Zhu, H., Pei, H. & Shi, B. Rheological behaviors of Na-montmorillonite considering particle interactions: A molecular dynamics study. Journal Rock. Mech. Geotech. Engineering, 17, 7, pp. 4657–4671, 2025/07/01/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.07.003

Khan, M. M. H. et al. Effect of various powder content on the properties of sustainable self-compacting concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02274. 2023/12/01/ (2023).

Datta, S. D. et al. Analysis of the characteristics and environmental benefits of rice husk ash as a supplementary cementitious material through experimental and machine learning approaches, Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 121, 2024/03/28 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-024-01423-7

Habibur Rahman Sobuz, M. et al. Performance of self-compacting concrete incorporating waste glass as coarse aggregate. Journal Sustainable Cement-Based Materials, 12, 5, pp. 527–541, 2023/05/04 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2022.2086936

Rana, A., Kalla, P. & Csetenyi, L. J. Recycling of dimension limestone industry waste in concrete. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 31 (4), 231–250 (2017).

Ashish, D. K. Concrete made with waste marble powder and supplementary cementitious material for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 716–729 (2019).

Demirel, B. & Alyamaç, K. E. Waste marble powder/dust, in Waste and Supplementary Cementitious Materials in Concrete: Elsevier, 181–197. (2018).

Kabbo, M. K. I. et al. Experimental assessment and machine learning quantification of structural Eco-Cellular lightweight concrete incorporating waste marble powder and silica fume. Journal Building Engineering, 105, 112557, (2025).

Zhou, H., Liu, Z., Shen, W., Feng, T. & Zhang, G. Mechanical property and thermal degradation mechanism of granite in thermal-mechanical coupled triaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 160, 105270 (2022).

Zhou, H., Liu, Z., Liu, F., Shao, J. & Li, G. Anisotropic strength, deformation and failure of gneiss granite under high stress and temperature coupled true triaxial compression. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16 (3), 860–876 (2024).

Sun, G., Kong, G. Q., Liu, H. & Amenuvor, A. Vibration velocity of X-section cast-in-place concrete (XCC) pile–raft foundation model for a ballastless track. Can. Geotech. J. 54 (04), 1340–1345. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2015-0623 (2017).

Zheng, Y. & Baudet, B. A. Pore structure response of reconstituted Kaolin and illite-smectite mixed-layer rich clay to 1D compression. Appl. Clay Sci. 276, 107892 (2025).

Zheng, Y., Zhu, T., Chen, J., Shan, K. & Li, J. Relationship Between Pore-Size Distribution and 1D Compressibility of Different Reconstituted Clays Based on Fractal Theory, Fractal and Fractional, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 235, [Online]. (2025). Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2504-3110/9/4/235

Aliabdo, A. A., Abd Elmoaty, M. & Auda, E. M. Re-use of waste marble dust in the production of cement and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 50, 28–41 (2014).

Peng, Y. et al. Evaluation framework for bitumen-aggregate interfacial adhesion incorporating pull-off test and fluorescence tracing method. Construction Building Materials, 451, p. 138773, 2024/11/15/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138773

Khan, K. et al. Exploring the use of waste marble powder in concrete and predicting its strength with different advanced algorithms, Materials, vol. 15, no. 12, p. 4108, (2022).

Mashaly, A. O., El-Kaliouby, B. A., Shalaby, B. N., El–Gohary, A. M. & Rashwan, M. A. Effects of marble sludge incorporation on the properties of cement composites and concrete paving blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 731–741 (2016).

Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: our Common Future (UN, 1987).

Hasan, N. M. S. et al. Investigation of lightweight and green concrete characteristics using coconut shell aggregate as a replacement for conventional aggregates. International J. Civil Engineering, 22, 1, pp. 37–53, 2024/01/01 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-023-00881-x

Hasan, R. et al. Eco-friendly self-consolidating concrete production with reinforcing jute fiber. Journal Building Engineering, 63, p. 105519, 2023/01/01/ 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105519

Sha, F., Wang, Q., Wang, N., Liu, F. & Ni, L. Performance of underwater shield synchronous double-liquid plastic Grout with high W/C and volume ratio. Construction Building Materials, 465, p. 140172, 2025/02/28/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140172

Zhao, J. et al. Three-dimensional strength and deformation characteristics of calcareous sand under various stress paths. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84 (1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-025-04083-8 (2025). /01/16 2025.

Uddin, M. A. et al. The effect of curing time on compressive strength of composite cement concrete. Appl. Mech. Mater. 204–208. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.204-208.4105 (2012).

Mishra, M., Keshavarzzadeh, V. & Noshadravan, A. Reliability-based lifecycle management for corroding pipelines, Structural Safety, vol. 76, pp. 1–14, 2019/01/01/ 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strusafe.2018.06.007

Amin, M. N., Khan, K., Saleem, M. U., Khurram, N. & Niazi, M. U. K. Aging and curing temperature effects on compressive strength of mortar containing lime stone quarry dust and industrial granite sludge, Materials, vol. 10, no. 6, p. 642, (2017).

Huang, H., Guo, M., Zhang, W. & Huang, M. Seismic behavior of strengthened RC columns under combined loadings. J. Bridge Eng. 27 (6), 05022005 (2022).

Mottakin, M. et al. Evaluation of textile effluent treatment plant sludge as supplementary cementitious material in concrete using experimental and machine learning approaches. Journal Building Engineering, 96, p. 110627, 2024/11/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110627

Ghorbani, S., Taji, I., Tavakkolizadeh, M., Davodi, A. & De Brito, J. Improving corrosion resistance of steel rebars in concrete with marble and granite waste dust as partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 185, 110–119 (2018).

Alyousef, R., Benjeddou, O., Khadimallah, M. A., Mohamed, A. M. & Soussi, C. Study of the Effects of Marble Powder Amount on the Self-Compacting Concretes Properties by Microstructure Analysis on Cement‐Marble Powder Pastes, Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. no. 1, p. 6018613, 2018. (2018).

Ergün, A. Effects of the usage of diatomite and waste marble powder as partial replacement of cement on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (2), 806–812 (2011).

Demirel, B. The effect of the using waste marble dust as fine sand on the mechanical properties of the concrete. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 5 (9), 1372–1380 (2010).

Binici, H., Kaplan, H. & Yilmaz, S. Influence of marble and limestone dusts as additives on some mechanical properties of concrete. Sci. Res. Essay. 2 (9), 372–379 (2007).

Buyuksagis, I. S., Uygunoglu, T. & Tatar, E. Investigation on the usage of waste marble powder in cement-based adhesive mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 154, 734–742 (2017).

Zhang, W., Liu, X., Huang, Y. & Tong, M. N. Reliability-based analysis of the flexural strength of concrete beams reinforced with hybrid BFRP and steel rebars. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 22 (4), 171 (2022).

Wang, K., Cao, J., Ye, J., Qiu, Z. & Wang, X. Discrete element analysis of geosynthetic-reinforced pile-supported embankments. Constr. Build. Mater. 449, 138448 (2024).

Askari, D. F. A. et al. Assessing the impact of pozzolanic materials on the mechanical characteristics of UHPC: analysis, and modeling study. Discover Civil Eng. 2 (1), 96 (2025).

Sun, L., Wang, X. & Zhang, C. Three-dimensional high fidelity mesoscale rapid modelling algorithm for concrete, Structures. 70, 107561 (2024).

Long, X., Iyela, P. M., Su, Y., Atlaw, M. M. & Kang, S. B. Numerical predictions of progressive collapse in reinforced concrete beam-column sub-assemblages: A focus on 3D multiscale modeling. Eng. Struct. 315, 118485 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Application of the non-linear three-component model for simulating accelerated creep behavior of polymer-alloy geocell sheets. Geotextiles Geomembranes, 53, 1, pp. 70–80, 2025/02/01/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geotexmem.2024.09.005

Alkharisi, M. K. & Dahish, H. A. The Application of Response Surface Methodology and Machine Learning for Predicting the Compressive Strength of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Containing Polypropylene Fibers and Supplementary Cementitious Materials, Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 2913, (2025).

Alahmari, T. S., Kabbo, M. K. I., Sobuz, M. H. R. & Rahman, S. A. Experimental assessment and hybrid machine learning-based feature importance analysis with the optimization of compressive strength of waste glass powder-modified concrete. Mater. Today Commun. 44, 112081 (2025).

Dahish, H. A. & Almutairi, A. D. Compressive strength prediction models for concrete containing nano materials and exposed to elevated temperatures. Results Eng. 25, 103975 (2025).

Niu, Y., Wang, W., Su, Y., Jia, F. & Long, X. Plastic damage prediction of concrete under compression based on deep learning. Acta Mech. 235 (1), 255–266 (2024).

Hu, D., et al., Machine Learning–Finite Element Mesh Optimization-Based Modeling and Prediction of Excavation-Induced Shield Tunnel Ground Settlement. Int. J. of Comput. Methods. 22(04): p. 2450066 (2024).

Hu, D. et al. Machine Learning–Finite element mesh Optimization-Based modeling and prediction of Excavation-Induced shield tunnel ground settlement. Int. J. Comput. Methods. 22 (04), 2450066. https://doi.org/10.1142/s021987622450066x (2025).

Ahmad, S. A., Mohammed, B. K., Rafiq, S. K., Ali, B. H. S. H. & Fqi, K. O. Different statistical modeling to predict compressive strength of high-strength concrete modified with palm oil fuel Ash. Emerg. Technol. Eng. J. 1 (1), 57–76 (2024).

Karim, F. R., Rafiq, S. K., Ahmad, S. A., Mahmood, K. O. F. & Mohammed, B. K. Soft computing modeling including artificial neural network, non-linear, and linear regression models to predict the compressive strength of sustainable mortar modified with palm oil fuel ash, Construction, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 52–67, (2024).

Fathy, I. N., Dahish, H. A., Alkharisi, M. K., Mahmoud, A. A. & Fouad, H. E. E. Predicting the compressive strength of concrete incorporating waste powders exposed to elevated temperatures utilizing machine learning. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 25275 (2025).

Sobuz, M. H. R. et al. Assessing the influence of sugarcane Bagasse Ash for the production of eco-friendly concrete: experimental and machine learning approaches. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, p. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02839 (2024). e02839, 2024/07/01/.

Ahmad, S. A., Ahmed, H. U., Rafiq, S. K., Jafer, F. S. & Fqi, K. O. A comparative analysis of simulation approaches for predicting permeability and compressive strength in pervious concrete. Low-Carbon Mater. Green. Constr. 2 (1), 10 (2024).

Mishra, M. et al. Experimental assessment and data-driven hybrid machine learning quantification with parametric optimization of compressive strength of ceramic waste concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 23, p. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e05043 (2025). e05043, 2025/12/01/.

Aditto, F. S. et al. Fresh, mechanical and microstructural behaviour of high-strength self-compacting concrete using supplementary cementitious materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02395 (2023).

Alkharisi, M. K., Dahish, H. A. & Youssf, O. Prediction models for the hybrid effect of nano materials on radiation shielding properties of concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03750 (2024).

Ahmad, D. A., Al Goody, A. Y., Askari, D. F. A., Ahmad, M. R. J. & Ahmad, S. A. Evaluating the effect of using waste concrete as partial replacement of coarse aggregate in concrete, experimental and modeling. J. Building Pathol. Rehabilitation. 10 (1), 11 (2025).

Barkhordari, M. S., Armaghani, D. J., Mohammed, A. S. & Ulrikh, D. V. Data-driven compressive strength prediction of fly ash concrete using ensemble learner algorithms, Buildings, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 132, (2022).

Ashrafian, A. et al. Classification-based regression models for prediction of the mechanical properties of roller-compacted concrete pavement. Appl. Sci. 10 (11), 3707 (2020).

Naderpour, H., Rafiean, A. H. & Fakharian, P. Compressive strength prediction of environmentally friendly concrete using artificial neural networks. J. Building Eng. 16, 213–219 (2018).

Afzal, A. et al. Human thermal comfort in passenger vehicles using an organic phase change material–an experimental investigation, neural network modelling, and optimization. Build. Environ. 180, 107012 (2020).

Afzal, A., Alshahrani, S., Alrobaian, A., Buradi, A. & Khan, S. A. Power plant energy predictions based on thermal factors using ridge and support vector regressor algorithms, Energies, vol. 14, no. 21, p. 7254, (2021).

Veza, I. et al. Review of artificial neural networks for gasoline, diesel and homogeneous charge compression ignition engine. Alexandria Eng. J. 61 (11), 8363–8391 (2022).

Bakır, H. et al. Forecasting of future greenhouse gas emission trajectory for India using energy and economic indexes with various metaheuristic algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 360, 131946 (2022).

Al-kahtani, M., Zhu, H., Ibrahim, Y. E., Haruna, S. & Al-qahtani, S. Study on the mechanical properties of Polyurethane-Cement mortar containing nanosilica: RSM and machine learning approach, Applied Sciences, 13(24), 13348 (2023).

Sadek, D. M., El-Attar, M. M. & Ali, H. A. Reusing of marble and granite powders in self-compacting concrete for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 121, 19–32 (2016).

Uysal, M. & Sumer, M. Performance of self-compacting concrete containing different mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (11), 4112–4120 (2011).

ASTM. ASTM C143/C143M-12, Standard test method for slump of Hydraulic-Cement concrete. ASTM Int. West. Conshohocken PA, (2015).

ASTM. C39/C39M-20, standard test method for compressive strength of cylindrical concrete specimens. ASTM Int. West. Conshohocken PA, (2020).

ASTM. ASTM C1723-16, Standard guide for examination of hardened concrete using scanning electron microscopy. ASTM Int. West. Conshohocken PA, (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Compressive strength prediction of high-strength concrete using long short-term memory and machine learning algorithms, Buildings, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 302, (2022).

Momshad, A. M. et al. Assessing the engineering properties and environmental impact with explainable machine learning analysis of sustainable concrete utilizing waste banana leaf Ash as a partial cement replacement. Cleaner Eng. Technology, p. 100886, 2025/01/09/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2025.100886

Barış, K. E. & Tanaçan, L. Earth of datca: development of pozzolanic activity with steam curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 139, 212–220 (2017).

Kaloop, M. R., Kumar, D., Samui, P., Hu, J. W. & Kim, D. Compressive strength prediction of high-performance concrete using gradient tree boosting machine. Constr. Build. Mater. 264, 120198 (2020).