Abstract

Identifying influential nodes in complex networks is critical for regulating information dissemination and mitigating disasters induced by misinformation, yet current methods for detecting such nodes typically rely exclusively on local topological features or global positional information–failing to leverage critical insights from neighbors with similar community memberships (i.e., nodes within the same community share the same community affiliation) in the network’s inherent community structure, which frequently results in low recognition accuracy and poor generalization across diverse datasets. To address this gap, we propose a novel semi-local metric, Local Community Structure Entropy (LCE), for identifying influential nodes in complex networks: LCE fully integrates information entropy with the network’s intrinsic community architecture by incorporating the connectivity magnitude of community structures, and specifically, we first partition the network into distinct communities using a community detection algorithm, then calculate each node’s entropy centrality based on first-order neighbor information, before further extending the analysis to second-order neighbor data to derive a comprehensive entropy centrality index. To validate LCE’s performance, we conduct extensive experiments on both social and synthetic networks, employing multiple evaluation metrics (the Susceptible–Infected–Recovered (SIR) model, Kendall’s correlation coefficient, complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF), community partitioning effectiveness, spreading efficiency, and computational complexity) and performing comparative tests against seven benchmark algorithms (Degree Centrality (DC), Betweenness Centrality (BC), K-shell decomposition (KS), Chance-Based Centrality (CBC), Community-Based Measure (CBM), Intra-Community Centrality (ICC), and Entropy-Renewal Heuristic (EnRenew)), and experimental results demonstrate that LCE outperforms all competing methods in terms of recognition capability while simultaneously improving efficiency and universality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the natural realm and human societies, myriad entities maintain intricate symbiotic relationships. These multifaceted systems can be distilled into frameworks characterized by nodes and linkages, such as the social interconnectedness1, transport systems2, the electrical grid infrastructures3,4, viral advertising5 and cascading failure of power grid6. Within these vast relational networks underpinned by prodigious data volumes, some key cadres in all nodes modulate information dissemination and oversight. Especially in the social network, key users as carriers of information dissemination and interchange, has a significant impact on the study of influence maximization7. Isolating and controlling these influential nodes holds tangible implications for real-world applications in a rapid and efficient way8,9. Currently, scholars have endeavored to craft intricate networks by leveraging data from platforms like the social media, and quantified node influence based on the constructed network model above10.

Some studies on influential nodes are increasing focusing on the intrinsic properties of networks topologies11. Some academics, drawing insights from proximate nodal data, have probed into the prominence of individual nodes12. A particularly intuitive approach is the degree centrality conceptualized by Freeman et al13.. At the heart of this proposition lies the tenet that a node’s significance is amplified by an abundance of its neighboring connections. K-shell decomposition is a coarse method of dividing the network hierarchy, which uses the degree information of each node to remove them from bottom to top14. This approach represents nodes in the inner shell have higher influence. In15, Closeness centrality proposed by Freeman et al. concerned mainly with spreading time of information in networks and computed the average distance between all nodes. Betweenness centrality was proposed to confirm that the number of shortest paths that pass through a node is be in proportion to the node’s influence16. In addition, frequently used classical algorithms such as eigenvector centrality17, pagerank centrality18, subgraph centrality19 and H-index20, they all have their own advantages to deal with the problem of the recognition effect under different situations.

However, classical methods suffer from excessive computational complexity, low recognition accuracy, and poor generalization. For reaching better effects, Chen et al21. unveiled a method of local centrality evaluation that meticulously inspects multi-step neighborhood data, which facilitats a nuanced analysis of nodal influence. Gao et al22. discerned that nodes that have same semi-local centrality exhibited amplified propagation capabilities if surrounded by densely interconnected neighbors. By leveraging the node’s clustering coefficient, they gauged the intensity of connections among its neighbors, consequently introducing a local structural centrality paradigm. Another scholastic finding23also proposed a node significance measure with the improved cluster by considering common hierarchy of nodes and their neighborhood set. Yang et al24. proposed a local method that considered a sub-network structure consisting of a number of shells in neighbors. Wen et al25. thought that increasing to half of the maximum value of the shortest distance from the central node can contribute on the improvement of identifying effects by combining the local structural properties. Tong et al26. considered connected and unconnected neighbors information to survey node inluence based on the hierarchical structure by using interpretative structure and shortest path distance.

Additionally, several researchers present a series of broader and holistic approach from the global perspective27. For instance, Sabidussi et al28. introduced the notion of closeness and betweenness centrality in view of the shortest path distance. Liu et al29. proposed the improved K-shell decomposition to address the issue that all nodes fail to be separated in same layer by using K-shell decomposition. Yang et al30. computed the sum of the K-Shell decomposition of the neighbors within 2-step of a node, and proposed an Extended Local K-Shell Sum (ELKSS) method to find influential nodes. Namtirtha et al31. designed a semi-global centrality to promote identifying precision from the dense part of a network, which maximized the total collective significance of a spreading process by selecting the best nodes. Ma et al32. employed the gravity formula and regarded the result of K-shell as node’s mass, and proposed a new gravity centrality to detect the influential nodes. However, these findings above only studied the method based on local information or studied global approach under position information, and failed to merge the local environment into the global position in recognition models33.

With this consideration, several experts considered that a unidimensional examination of structural attributes is inadequate for a holistic assessment of node importance, so they designed kinds of constructive measures on hybrid information34. Zhang et al35. proposed a multi-scale centrality algorithm under some traditional methods for mining influential nodes, where rigorous experimental verifications underscored the practicality of this method. Tong et al36. discovered the internal action and external action in the subnet structure in neighbors, and designed a effective identifying hybrid model based on the global hierarchical structure. Meng et al37. presented a novel potential edge weight method that incorporated position of node, neighborhood information, and topological structure features to hunt influential nodes. However, a recurring theme in these evaluative paradigms, whether local, semi-local or global, has been their inherent propensity to assess node importance at a microcosmic level from the individual node perspective. In a more mesoscopic understanding of networks, each entity invariably belongs to multifarious groups and social clusters. Therefore, experts began to propose some divergent community division algorithms by introducing characteristics of community structures to the identifying model based on topological information when recognizing that real-world social networks invariably exhibit pronounced community structures38,39. Hu et al40. articulated an innovative K-shell and community centrality evaluation model, which effectively amalgamated the K-shell centrality of the node with the intrinsic attributes of its community to discern its sphere of influence. Kumar et al41. introduced three factors community diversity, community modularity and community density into evaluating influential nodes, which can effectively solve the problem of influence maximization. To reduce the time complexity by the way of compressing the search space, Bouyer et al42. came up with the FIP algorithm to monitor the overlapping communities and analyse the connection among the community’s nodes. This method mainly concerns the community internal structure and spreading ability of overlapped nodes between communities, which contributes on finding influential seed nodes in complex networks. In addition, Zhang et al43. studied the identifying nodes’ influence issue brought by the community structure and the influence distribution difference.

It can be seen that the research on the importance of nodes combining topological information with characteristics of community structure is particularly necessary from the literatures above. In this paper, we propose a novel measure named Local Community Structure Entropy (LCE) to find influential nodes in complex networks. The method fully combines information entropy with the intrinsic community architecture by considering the magnitude and multiplicity of connections of community structure. First, we segment the network into distinct communities by harnessing the community detection algorithm, and compute the node’s entropy centrality. Furthermore, we deduce the entropy centrality index and classify nodes based on their respective indices. Additionally, we employs seven algorithms including the Degree Centrality (DC)13, Betweenness Centrality (BC)16, K-shell decomposition (KS)14, Chance-Based Centrality (CBC)44, Community-Based Measure (CBM)45, Intra-Community Centrality (ICC)46 and Entropy-Renewal Heuristic (EnRenew)47 to conduct comparison tests for representing the performance of the proposed method. In the experiments, we adopts a series of indicators, including Susceptible–Infected–Recovered (SIR) model, Kendall’s coefficient, complementary cumulative distribution function, determination of community division, spreading efficiency and complexity to execute corresponding experiments and evaluate the performance on social and synthetic networks. Results demonstrate that, the proposed method outperforms involved algorithms in the recognition capability and promotes efficiency and universality.

The remainder of contents consists of four parts as follows. In Section 2, concepts and formulas of involved measures are briefly introduced for comparison and analysis in the experiment part. In Section 3, the designed process of proposed algorithm is expounded and verified by a simple network. Section 4 confirms good performance of LCE by a series of simulation experiments. The summary of the whole paper is presented in section 5.

Related works

The multifaceted influence evaluation algorithms underscored in this paper encompass various metrics. Let us introduce and elucidate them as follow briefly.

Definition 1

The Degree Centrality (DC)13 is quantified by the degree of a given node, representing the count of adjacent nodes connected to it. Formally, the DC method can be articulated as:

where \(|N |\) is the number of nodes in the network, and \(a_{ij}\) means that node i and node j have a relationship.

Definition 2

In instances where myriad pathways intersect at a singular node within a network, the betweenness centrality16 of that node is usually of great importance. This centrality can be delineated as:

where \(L_{jk}\) is all the shortest paths from node j to node k, and \(L_{jk}\left( i\right)\) is all the shortest paths from node j to node k that need to pass through node i.

Definition 3

The K-shell decomposition14 commences by purging all nodes of degree \(k=1\) from the network. Proceeding iteratively, it then expunges nodes with a degree of \(k\le 1\) until no nodes with a degree less than or equivalent to 1 persist within the network. Based on the shell divisions, one can ascertain the shell value of individual node. The fact that a node has higher shell shows that it has great significance.

Definition 4

Chance-Based Centrality (CBC)44 serves as a paramount tool for discerning influential nodes within probabilistic communities. It sets two distinct categories of connections: intra-community links dubbed ’strong links’, and inter-community links called ’weak links’. The prominence of a node is contingent upon both the robustness of its affiliations and the magnitude of the community to which it is affiliated. The computational expression for this is provided below:

where c is the number of communities in the network, \(a_{iw}\) is the number of connections between node i and one node in community w, and \(S_{w}\) is the number of nodes in community w.

Definition 5

The Community-Based Measure (CBM)45 is judiciously conceptualized as an enhancement of the CBC method. It sufficiently factors in the nuanced influence of community architecture and innovates by integrating the principle of gauging influence through the lens of information entropy. The computational framework for this approach is delineated in a tripartite progression, as elucidated below:

where \(p_{i}^{in}\) is the internal density of node i, \(a_{ij}\) is the number of connections between i and j belonging to a community, and \(d_{i}\) is the total degree of i. According to this formula, the entropy index \(H_{i}\) of node i can be obtained.

The \(CBM\left( i\right)\) of node i is shown as follows:

where \(d_{i}\) is the total degree of node i.

Definition 6

The Intra-Community Centrality (ICC)46 method systematically discerns influential nodes by meticulously examining the interwoven density of the network juxtaposed with its community architecture. The algorithmic representation is as follows:

where \(CC_{i}\) is the closeness of node i, \(D_{ij}\) is the shortest distance between node i and node j, \(N_{C_{i}}\) is the number of all nodes in the community where node i is located, N is the size of the entire network, \(R_{i}\) represents the number of communities except the community where i is located, \(N_{C_{w}}\) is the number of all communities contained in community w, and node j belongs to community w and is directly connected to node i.

Definition 7

The Entropy-Renewal Heuristic (EnRenew)47 derives its foundation from VoteRank. This heuristic imbues the original algorithm with entropy-based principles, dynamically updating node entropy via iterative selections. This inclusion obviates the inherent shortcoming in VoteRank, which has a propensity to overlook the granular and localized data associated with nodes.

where \(p_{uv}=\frac{d_{u}}{\sum _{l\in \Gamma _{v}}d_{l}}\), \(\sum _{l\in \Gamma _{v}}p_{lv}=1\), \(\Gamma _{v}\) is the nearest neighbors of node v, \(d_{u}\) is the degree of node u, and \(H_{uv}\) is the propagation capability of node u to node v.

Methods

The research of networks is based on graph theory and expressed in the form of graphs. Mathematically, a network can be depicted as a graph \(G=\left( V,E\right)\) composed of nodes and connections. The most common model used to represent the node and its connected relationship is the adjacency matrix. For an undirected and unweighted network \(G=\left( V,E\right)\) with N nodes, its adjacency matrix can be expressed as a square matrix of N rows and N columns. \(a_{vw}\) denotes the elements in the v row and w column of the matrix. If a connection exists between the nodes v and w, then \(a_{vw}=1\) in the matrix; otherwise, \(a_{vw}=0\). In an undirected network, \(a_{vw}=a_{wv}\), and the adjacency matrix is a symmetric matrix.

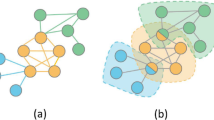

The architectural composition of communities constitutes a salient feature of real-world network topologies48. Such a community is characteristically delineated as an ensemble of nodes intrinsically interconnected, which is juxtaposed with more tenuous links to external node conglomerates49. Therefore, division of community in a network is most necessary when studying influence recognition model. Especially in designing process of algorithms, it must take into full consideration of community segmentation. Various division methods were proposed aimed at amplifying both the precision and efficacy of community segmentation50,51,52,53,54. Following empirical juxtapositions with extant community segmentation methods, the Louvain community division algorithm has emerged55. This division method, attributable to its rapid computational cadence coupled with its formidable efficacy, has burgeoned into a predominant choice amongst community segmentation algorithms.

Position of nodes within and beyond the community structure exerts important influences when calculating node influence. For reaching better identifying effects by using the division method, in this paper, the information entropy56 is introduced to create a recognition model. Mathematician Shannon referred to the concept of thermal entropy in thermodynamics in physics and proposed the concept of information entropy to measure and explain the uncertainty of information sources. If X consists of a set of possible events \(x_{1},x_{2},\cdots ,x_{n}\), and \(p_{i}\) is the probability of \(x_{i}\), then the information entropy of X can be calculated as

It can be obtained that if the probabilities are uniformly distributed on X, then the maximum value of entropy will be obtained. The entropy value also increases as the value of n increases.

Given community structural attributes across diverse networks, this study endeavours to quantify node significance predicated upon their inherent attributes within such community architectures. To illustrate it, an individual possessing a myriad of affiliations across disparate domains within a social network might be postulated to wield influence across a more heterogenous gamut of social strata. Though abundant affiliations might exist, a solitary community often circumscribes the ambit of one’s clout. Hence, key nodes tethered by the multifarious natures of communities, which has a impact on the relationship between the community internal structure and the intercommunity structure. Concurrently, as one navigates the cascade of individual influence dissemination, one observes an inherent clustering predilection. Events such as information propagation or pathogenic spread often initiate within community confines, subsequently radiating outwards. Such as a community’s magnitude, bolstered by the dense inter-connectivity of its constituents, amplifies its susceptibility to such cascades. So the dimension of the community is paramount in adjudging a node’s significance within this network. (Rajeh et al. 2015)

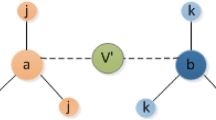

Based on the above exposition and the principle of entropy weighting, the dual attributes of community magnitude and community connectivity are combined to calibrate a node’s influence quotient. Thus, the concept of entropy centrality is introduced, anchored firmly within the paradigm of community structure. Formally, the entropy centrality of node v is computed as:

where \(u\in \Gamma _{v}\) represents the neighbor set of node v. \(T_{u}\) represents the size of the community to which node u belongs as shown in Fig. 1, which is the sum of the number of nodes in the community. Here we adopt a commonly used method \(\varphi _{C}\) for community detection. More individuals are affected by the node when its value is larger. At the same time, if the \(\frac{T_{u}}{\sum _{u\in \Gamma _{v}}T_{u}}\) value distribution is more uniform, then the number of connected communities is more and is not only limited to a single community connection. Therefore, the \(E\left( v\right)\) index of the node can comprehensively consider the two characteristics of the size and quantity of the community.

Concurrently, as one delves into the dynamics of nodes’ influence propagation, it becomes evident that information percolates initially through proximate neighbors within disparate communities. Ignoring lower-order neighbors information can also have impacts on the influence precision. Building upon this reason, identifying effect of each node need to acquire more neighbors information based on community structure entropy pertaining to nodes. Thus, the extended centrality metric in neighbors is articulated as:

where \(u\in \Gamma _{v}\) represents the set of neighbor nodes of node v.

Algorithm 1 shows the pseudo code of the designed method LCE that consists of details of the calculation steps. For showing specific operational details by LCE, we employ a toy rudimentary network as shown in Fig. 2. In LCE, we set that the Louvain algorithm replace \(\varphi _{C}\) to partition this network structure into distinct communities. As shown in Fig. 2 that communities are discerned through varying chromatic delineations. Nodes \(v_{3}\), \(v_{4}\), \(v_{5}\) and \(v_{6}\) coexist within a singular community; nodes \(v_{1}\), \(v_{15}\), \(v_{16}\), \(v_{13}\), \(v_{18}\), \(v_{19}\) and \(v_{20}\) share another; and nodes \(v_{2}\), \(v_{7}\), \(v_{8}\), \(v_{9}\), \(v_{10}\), \(v_{11}\), \(v_{12}\), \(v_{13}\) and \(v_{14}\) comprise the third.

Table 1 proffers a comparative analysis juxtaposing the LCE sorting methodology against alternate sorting paradigms within this toy network, supplementing the discourse with the raw LCE values, SIR dissemination outcomes, and inherent SIR values for a comprehensive understanding. Subsequently, Table 2 leverages the insights from Table 1 for a Kendall coefficient computation. It is noteworthy that solely the LCE methodology boasts a Kendall value surpassing 0.8, epitomizing optimal performance in this context.

The computation for the LCE valuation pertaining to node \(v_{2}\) is rendered as:

The LCE value of \(v_{2}\) is

Experimental study

In this section, to authenticate the efficacy of the proposed Community Structure Entropy Centrality (LCE), we have selected a gamut of representative evaluation methodologies, spanning local, global, and other community-structure anchored paradigms for comparative analysis. They encompass Degree Centrality (DC), Betweenness Centrality (BC), K-shell decomposition (KS), Chance-Based Centrality (CBC), Community-Based Measure (CBM), Intra-Community Centrality (ICC) and Information Entropy (EnRenew). More important, we determine a method of community division to replace \(\varphi _{C}\) in the LCE model for reaching better effects. Therefore, we introduce EM50, GN51, LPA53, SCAN54 and LOUVAIN as community division methods participate in the experiment of the community segmentation to embody superiority of the proposed method. In addition, eight social and synthetic networks as research subjects take part in a series of experiments including the determination of community division method, the correlation, ranking, spreading efficiency and complexity.

Experimental data

In light of the complexities and intrinsic nuances of real-world networks, individual networks exhibit profound variations in their structural attributes. To comprehensively verify the performance of the proposed LCE method across diverse network scenarios, we selected 8 representative social and synthetic networks as experimental subjects. These networks cover different scales (from 34 nodes to 4941 nodes) and structural characteristics, ensuring the universality of the experimental results. The key structural attributes of the selected networks are quantified and summarized in Table 3, and each attribute is defined as follows to clarify its physical meaning:

n:Network size, i.e., the total number of nodes in the network.

m: Total number of connected edges in the network, reflecting the density of connections between nodes.

d_max (apex degree): The maximum degree of the network, which refers to the number of edges owned by the node with the most connections in the network (denoted as “apex degree” in the original text). It reflects the upper limit of connection capability of individual nodes in the network.

<d>: The average degree of the network, calculated as the total number of edges multiplied by 2 (for undirected networks) divided by the number of nodes, reflecting the average connection level of nodes in the network.

c: The clustering coefficient of the network, a measure of the degree to which nodes in the network tend to form tightly connected subgroups (clusters). A higher value indicates a more clustered network structure.

s: The number of communities divided by the network using the Louvain algorithm, reflecting the modularity of the network’s community structure.

A(homogeneity): Node degree distribution uniformly coefficient, which is complementary to the known concept of “degree heterogeneity” (a measure of the degree of variation in node degrees). Its calculation logic is based on the normalization of the node degree’s coefficient of variation (CV): first, calculate CV as the ratio of the standard deviation of node degrees to the mean (reflecting the dispersion of degree distribution); then normalize CV using the formula: \(A = 1 - 2 \times \frac{CV - CV_{\min }}{CV_{\max } - CV_{\min }} \quad (\text {where: } CV_{\min } \text { and: } CV_{\max } \text { are the minimum and maximum})\) \(CV\) values among all 8 experimental networks. The value range of A is \([-1,1]\); a value closer to 1 means the node degree distribution is more uniform (most nodes have similar connection counts); a value closer to 1 means the degree distribution is more discrete (the network has an obvious “core-periphery” structure, with a few nodes owning most connections); a value close to 0 indicates a moderately uniform degree distribution. This indicator, together with degree heterogeneity, forms the dual characteristics of network connection distribution, providing a basis for analyzing the adaptability of the LCE method to different structural networks.

’apex’ degree refers to the maximum degree of nodes in the network (denoted as d_max in Table 3), representing the number of edges owned by the node with the most connections in the network

Eight social and synthetic networks include (1) karate club network (Karate), (2) football network (Football), (3) Usair, (4) co-authored scientist network (Netscience), (5) Caenorhabditis elegans network (Elegans), (6) email network (Email), (7) European road network (Euroroad), and (8) Western power grid (Power grid).

Figure 3 elucidates both the topological architecture and the community structure subgraph of a segment of the network under study. Within the illustration, chromatic gradations serve to demarcate distinct community modules. Notably, certain networks manifest pronounced community structural attributes. These networks present a characteristic landscape where linkages are relatively diffuse in inter-community, yet nodes within individual communities demonstrate heightened intra-connectivity.

Determination of community division method

The community partitioning algorithm can profoundly have a impact on the ultimate ranking of node influence. In this subsection, we juxtaposed the Louvain method against four alternative community partitioning algorithms for interrogating their respective efficiencies. The ensuing table elucidates our experimental findings.

Arrayed along the table’s abscissa are the diverse community partitioning methodologies under examination, while the ordinate enumerates results from the eight involved networks. Additionally, the table enumerates various critical parameters: Q symbolizes the modularity achieved during community segregation, c quantifies the resultant community partitions, and r designates the theoretical propagation threshold. Furthermore, we furnish their respective Kendall correlation coefficient values of actual propagation rankings for each of the partitioning methods. Here, r epitomizes the value of Kendall correlation coefficient that juxtaposes our proposed methodology against actual propagation ranking outcomes, and evaluates the effects under the theoretical propagation threshold across the EM, GN, LPA, SCAN, and Louvain community partitioning paradigms.

Note: 1. Q (Modularity): Measures the quality of community division; the higher the value (ranging from −1 to 1), the more significant the community structure (i.e., denser internal connections and sparser inter-community connections).

2. c (Number of Communities): The number of communities obtained by dividing the network using the corresponding method. 3. Calculated by \(\beta _{th} = \frac{\langle k \rangle }{\langle k^2 \rangle }\), where \(\langle k \rangle\) is the average node degree and \(\langle k^2 \rangle\) is the average of squared node degrees; it reflects the critical infection probability for global SIR propagation. 4. r: Kendall correlation coefficient between LCE-based node influence ranking and SIR-based real influence ranking; higher values indicate better consistency.

As shown in Table 4 and 5, the inspection of the tabulated data reveals that the Louvain algorithm consistently boasts superior modularity across the eight networks. However, it marginally lags behind the GN algorithm by a mere 0.002 with the sole exception being the Euroroad network. When assessing the number of community partitions, Louvain emerges as the paragon, combining optimal community divisions with computation times that remain firmly within acceptable bounds. Across the entirety of the evaluated metrics, Louvain consistently delivers the most exemplary community segmentation outcomes. Most of all, the resultant Kendall coefficients exhibit minimal fluctuations which is irrespective of the variations in community segmentation methodologies, and their disparities remain under two orders of magnitude. These observations underscore both the robustness and the preeminence of the LCE algorithm.

For a more granular comprehension of the evaluative disparities inherent to LCE algorithm in various networks, we adopt Em, Gn, Lpa, Scan and Louvain, and utilize the Kendall value as our evaluating metric compared with CBC, CBM and ICC.

The experimental results are shown in Table 6. The table’s horizontal axis delineates community partitioning methods, and the vertical axis enumerates the CBC, CBM, ICC and LCE in eight experimental networks. Within this table, results of Kendall coefficient populate each cell. Optimal scores with delineated in bold stand out for each network. Within six networks, the Louvain method serves as the community segmentation apparatus, and LCE reigns supreme effects in all metrics of detecting node influence. While it does not clinch the pinnacle position within the Email, Netscience, and Usair networks, its deficits remain a negligible value of 0.022, 0.005, and 0.004, respectively.

Contrastingly, while certain impact detection algorithms may excel sporadically across select networks, LCE maintains an unyielding zenith of consistency and demonstrates admirable performance ubiquitously. It’s salient to note that augmentations of performance fail to be precipitated by modifications in the influence detection paradigm but rather via strategic alterations in the community segmentation algorithm. To elucidate them, LPA is employed to conduct community division in the Email network, and results are bolstered by 0.022. While in the Netscience network, the adopted GN can lead to an enhancement of 0.005. Similarly, resorting to LPA in the Usair network promotes outcomes by 0.004. The overarching analysis accentuates Louvain’s efficacy in elevating these results.

The excellent effect generated by LCE algorithm becomes palpable compared with other algorithms. It truly shines in expansive, intricate networks like Football, Power grid, Netscience, and Usair, bolstering them despite their intricate interconnections and multifaceted relationships. Significantly, applicable effects by using Louvain method in the LCE modeel for community division is demonstrated to surpass others in aspects of precision and efficiency.

Correlation based on SIR

In this subsection, our simulation experiment seeks to capture the genuine influence of nodes, grounding our approach in the archetypal dynamics process. The concordance between the influence ranks deduced from the evaluative method and that derived from the spreading model, would contribute on distinguishing the capacity of finding influential nodes in different methods. Therefore, we adopt the Susceptible–Infected–Recovered (SIR) infectious disease model to calculate real influence of each node. This model has wide ranges of applications in simulating the dissemination of information, ideologies, pathogens, and maladies within intricate networks. Within the SIR framework, nodes oscillate among three distinct states: susceptible (S), infected (I), and recovered (R). In the context of this manuscript, our designed methodology pivots on the following procedure. When gauging the dispersal prowess of an node, this node is designated as the primary infection nexus. Thus, this node is defined as the ’infected’ state (I), while the remainder of the network’s nodes are relegated to the ’susceptible’ state (S). Within each temporal increment, nodes in the infected state (I) transmit the contagion to its neighboring susceptible nodes with a probability that is denoted as \(\beta\). Subsequent to this transmission, the infected nodes transition to the recovered state (R), hence becoming immune and extricating itself from further propagation activities. Nodes newly infected persist in their propagation endeavors in a similar fashion. This dynamic ensues until the network is devoid of any nodes in the infected state (I). Concluding this propagation trajectory, the genuine dissemination influence of an individual node is encapsulated by the aggregate of nodes that have transitioned to the immune or recovered state (R) within the network. A total of 10,000 repetitive experiments are performed for the network with the number of nodes \(n<100\), and 1000 repetitive experiments are performed for the network with the number of nodes \(n>100\). The average value is finally taken. The selection of the infection probability \(\beta\) is usually greater than the propagation threshold \(\beta _{th}\)57, where \(\beta _{th}=\frac{\left\langle k\right\rangle }{\left\langle k^{2}\right\rangle }\), \(\left\langle k\right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle k^{2}\right\rangle\)represent the average degree of the node and the average of the square of the degree, respectively.

Kendall’s correlation coefficient58 is often used to measure the consistency of the two ranking results. Here, rank \(\sigma =\left( x_{1},x_{2},\cdots ,x_{n}\right)\) is used to represent the ranking result of influence calculated by a certain evaluation algorithm. Ranking \(\theta =\left( y_{1},y_{2},\cdots ,y_{n}\right)\) represents the impact ranking result generated by the SIR propagation model simulation. Any element in \(\sigma\) and \(\theta\) is taken to compare \(\left( x_{i},y_{i}\right)\) and \(\left( x_{j},y_{j}\right)\). If \(\left( x_{i}>x_{j}\right)\) and \(\left( y_{i}>y_{j}\right)\) or \(\left( x_{i}<x_{j}\right)\) and \(\left( y_{i}<y_{j}\right)\), then the ordering results of the two element pairs are consistent; if \(\left( x_{i}>x_{j}\right)\) and \(\left( y_{i}<y_{j}\right)\) or \(\left( x_{i}<x_{j}\right)\) and \(\left( y_{i}>y_{j}\right)\), then the sorting results of the two element pairs are inconsistent; if the sorting results of the two element pairs \(\left( x_{i}=x_{j}\right)\) and \(\left( y_{i}=y_{j}\right)\), then they are neither consistent nor inconsistent. Among them, the Kendall correlation coefficient is defined as

where \(N_{c}\) represents the number of consistent element pairs in any two element pairs in \(\sigma\) and \(\theta\), and \(N_{d}\) represents the number of inconsistent element pairs in \(\sigma\) and \(N_{d}\). The value range of \(\tau\) is [−1,1]. If \(\tau =1\), then the two sets of ranking results are completely consistent. Higher \(\tau\) value means higher consistency of the two rankings.

To gauge the efficacy of the proposed method, our analysis bifurcates into a duality of perspectives: the ramifications within the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model and the discernibility of node influence. Remarkably, the enhanced Kendall coefficient attains values of 88.14%,80.29%,88.32%,74.23%,82.80%,84.49%,75.59%, 75.59%, and 71.36% across the seven distinct networks except Email by using LCE, which exceeds against other approaches including DC, BC, KS, CBC, CBM, ICC, and EnRenew. As for the network of Email, CBC provides the Kendall correlation coefficient of 84.51\(\%\), which is slight higher than the result of 84.49\(\%\) obtained by LCE.

Table 7 elucidates the congruence between the theoretical influence ranking, as proffered by various algorithms proximate to the spread threshold, and the empirical dissemination influence ranking. Intriguingly, the subsequent column delineates the theoretical propagation threshold, whilst the succeeding column enumerates the chosen propagation probability for our experiments. The trailing columns furnish the Kendall correlation coefficient values, juxtaposing the ranking outcomes of DC, BC, KS, CBC, CBM, LCE, ICC, EnRenew, and the empirically observed propagation prowess. The tableau elucidates that, in proximity to the propagation threshold across the eight networks, LCE reigns supreme in capturing propagation influence, underscoring its superlative applicability across real networks.

To deeply delve and account for the undulations of Kendall correlation coefficient induced by changing propagation probability located in the neighbors of the threshold on the SIR model, we embark on supplementary simulation. These findings underscore that the relative hierarchy of the node propagation influence is concurrently modulated when the propagation probability experiences perturbations proximate to the propagation threshold. As shown in Fig. 4, the abscissa represents the propagation probability, the ordinate embodies the Kendall consistency coefficient, and chromatic distinctions in curves illustrate the consistency results obtained by the node evaluating influence rankings by diverse methods and the real influence rankings by the SIR model. It is obvious that the curve generated by LCE retains top value of Kendall correlation coefficient over other curves in all networks. Emphatically, experimental results attest to the superiority of the LCE approach in eight networks, which consistently soars its counterparts above and intimates that ranking effects of LCE has good performance in close proximity to real influence based on SIR.

By comparing the Kendall coefficients of each algorithm in Table 6 (LCE average 0.82, “CBC” average 0.75, “CBM” average 0.68) with the SIR real-world propagation rankings and the scatter plots in Figs. 6,7,8,9, we find that CBM performs significantly worse than other algorithms in key node identification. The core reason is closely related to its design logic flaws. A detailed analysis based on the formula and experimental data is as follows:

The core computational logic of CBM is (derived from reference [45]): \(CBM(i) = \frac{k_{in}(i)}{k(i)} \times Q\)

Among them, \(k_{in}(i)\) is the number of connections of node \(i\) in the community to which it belongs (intra-community degree), \(k(i)\) is the total number of connections of connections of node (total degree), and is the modularity index of community division.

Distinguishing ability of node influence

Distinguishing the influence of nodes under different algorithms is an arduous task which directly affects the spreading effect in the diffusion process. This segment of our analysis elucidates the discerning capability of the LCE algorithm in relation to influence of nodes. The granularity and precision of our sorting mechanism are elucidated via juxtaposition with alternate methods, employing the complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) as our metric of choice59. Mathematically, the CCDF is represented as:

On the contrary, if all nodes have a different arrangement order, that is, \(r\rightarrow n\), then the CCDF curve will slowly decrease. In other words, the influence of each node can be effectively distinguished after sorting by this index.

For a more systematical and intuitive illustration, we calculate corresponding value of each algorithm based on (18) and draw their tendency chart as shown in Figure 5. In Fig. 5, The X-axis represents the rank results evaluated by different involved methods, and the Y-axis means the probability of corresponding the rank result being higher than a given value. As delineated in these plots, approaches encompassing BC, CBC, ICC, EnRenew and notably LCE display admirable discriminatory prowess, which are marked by the gradual ebbing of their respective curves. In stark contrast, the granularity exuded by algorithms such as DC, KS and CBM appears decidedly rudimentary.

Intriguingly, within the ambit of the Karate network, ICC and EnRenew endeavors to fathom the intrinsic significance of nodes from a panoramic vista. Yet, their discerning acumen fall short of the elevated benchmark set forth by LCE. Turning our attention to the Football network, the CCDF trajectories of BC, ICC, EnRenew and LCE approach congruence, languidly receding in tandem along the diagonal.

In the realms of the PowerGrid and Euroroad networks, LCE exhibits its obvious advantage of distinction over other seven benchmarks because its curve surpasses others. As for Netscience, curve of LCE inferiors to ICC when rank \(r\le 100\), and the results of others tend to zero more quickly with a steeper slope in their plotted curves than LCE in the remaining stage. In the datasets of Usair and Elegans, the tendency of EnRenew and ICC in plotted curves are infinitely closer to the proposed method, which presents LCE has a slight better performance of distinguishing ability of node influence. However, this simulation reveals that curve of ICC has slower drop rate with other measures including LCE in Email. This phenomenon manifests that the distinguishing ability of LCE is slightly weaker than ICC. In summary, the proposed method provides overwhelming performance of distinguishing ability over others in most of datasets in view of its superiority of community entropy from adjacent nodes.

Comparison of LCE with other influence algorithms

In order to further study the relationship between the proposed method and CBC, CBM, ICC, EnRenew instead of classical algorithms such as DC, BC and KS,

we use the point scatter map to explore the correlation and discrimination between LCE and other algorithms.

In Fig. 6, the vertical axis represents the pristine outcomes derived from the LCE algorithm, while the horizontal axis elucidates the authentic results of the CBC algorithm. Obviously, eight scatter diagrams show the positive correlation between LCE and CBC. In Elegans and Usair, the results emerge a straight line between the proposed method and CBC, which represents their top consistency and similarity compared with other networks. Nonetheless, within the intricate landscape of the Power grid and Football networks, the outcomes of consistency appear conspicuously aberrant, whereas LCE consistently manifests commendable efficacy.

In the rest of datasets, the values proffered by LCE algorithm surpass those of the CBC method, culminating in a heightened discernment. This heightened distinction remains consistent even within diminutive networks. Such performance further corroborates the conclusions delineated in the aforementioned tableau.

As for the correlation and discrimination between LCE and CBM, the distribution of the scatter plot in all networks is shown in Fig. 7. It is conspicuous that the plots appear good correlation in Karate, Elegans and Usair and other scatter diagrams represents a discrete and disordered state between LCE and CBM. Expecially in Football, Euroroad and PowerGrid, the distribution of scattered points presents a completely irregular and chaotic form, where the difference of discrimination ability between LCE and CBM is large. CBM has a poor performance about identifying influential nodes in networks.

Similar to the above, the experiment results the correlation and discrimination between LCE and ICC are depicted as Fig. 8. Eight scatter diagrams show that both LCE and ICC exhibit commendable discriminating capabilities within the context of the Email and Usair networks. Nevertheless, within the confines of the Football network, the performance of the ICC algorithm starkly digresses from anticipated outcomes because of the irregular and chaotic distribution. In stark contrast, the outcomes proffered by the LCE algorithm stand as a paragon of reliability. Generally, LCE consistently outshines the ICC approach and displays superiority in the stability, precision and computational efficiency.

When it comes to the correlation and discrimination between LCE and EnRenew, the experiment results are simulated and drawn in Fig. 9. The plots unveil a consistent positive distribution across the mentioned networks, and underscore the proficient recognition effected by both algorithms. However, the performance of the EnRenew algorithm leaves much to be desired, especially within the Euroroad, Football and Power grid networks. As shown in Karate, Elegans, Email, Netscience and Usair, the phenomenon that the positive correlation exhibits a straight line represents their top consistency and similarity. Compared to CBC, CBM and ICC in the study above, the EnRenew method have superiority in the correlation and discrimination, but the effects generated by LCE with its equitably distributed and cogent values maintain good performance than EnRenew.

Spreading efficiency

Propagation dynamics within networks serve a pivotal metric in extant evaluation methodologies rooted in network topology. By emulating authentic propagation sequences, one gauges the ripple effect exerted upon the entirety of the network when distinct nodes are posited as the inaugural propagation foci. Consequently, a node yielding a more expansive sphere of influence inherently possesses augmented influence. For representing the diffusion efficiency of proposed method and other algorithms, we adopt the SIR model to simulate the dynamic process of propagation of each method. Through comparing the scale and degree of infection, the propagation effect of the proposed algorithm can be demonstrated. So a commonly used the concept of shortest path distance serves as the assessment indicator to survey the dynamic effect of each method in the process of transmission. The shortest path distance in networks is defined as follows.

where \(G_{infected}\left( t\right)\) refers to a infected network consisting of infected nodes at some propagation time t. \(D_{v,w}\) shows the shortest path distance between node v and w. \(N_{infected}\left( t\right)\) is the number of nodes in \(G_{infected}\left( t\right)\). In the experiment, the propagation parameters are the same as those set in the above experiments. Additionally, the range of propagation time is set between 0 and 20. The results of simulation test is shown as Fig. 10.

It is evident from Fig. 10 that LCE method has a superiority in all approaches. In two datasets of Netscience and Usair, the curve of LCE obviously keeps on top of others at every propagation time, which represents that LCE has a good performance of detecting influential nodes compared with other methods. In Football, the curve of LCE remains slight edge over others although CBC, CBM and EnRenew come close to LCE. In Euroroad, Elegans, PowerGrid and Email, we find that the effect of LCE inferiors to part of other approaches within the front short period of propagation time. ICC, EnRenew and BC can provide higher spreading effects over LCE in PowerGrid, and the curves of CBC and BC also have good performance than LCE in Elegans, and BC can provide good diffusion effect over LCE in Email in this previous stage. Especially in Euroroad, LCE inferiors to ICC before the 3rd propagation time, the curve of LCE is over all curves by a particularly great advantage in the remaining propagation time. As for Karate, curves of other approaches are near to LCE except KS. LCE is lower than CBC, DC and ICC before the 2nd propagation time, and BC exceeds LCE from the 10th time to the 14th time. In the remaining propagation time, the proposed method provides slight advantage over others. To sum up, this diffusion experiment demonstrates that the proposed LCE can give excellent presentation of spreading efficiency than other involved methods in eight datasets.

Complexity analysis

Time complexity, depending on program running times and cost, is commonly employed as a reliable evaluation criterion to detect the quality of an algorithm. If the time complexity of a method is higher, it shows that excessive costs are consumed and it has a disadvantage of running of the program. In this section, it mainly tests running effects of all involved approaches. Table 8 shows the time complexity of different methods and affiliated categories.

The computational complexity of LCE consists of two parts. In this method, the first part of complexity mainly study community structure. For detecting community structure rapidly, the proposed method adopts the Louvain algorithm to assign communities each node belonging to. By traversing all nodes in the network, they are divided into corresponding communities and the size of the community each node belongs to \(T_{v}\) can be calculated. Therefore, the time complexity of this part is O(nlogn), where n represents the number of nodes in the network. The other part mainly concerns the extended metrics in neighbors. At first, we need to calculate the sum of community size of neighbors of v belonging to, whose the time complexity of this stage is O(n). Secondly, the entropy centrality of node v based on 11 is computed and the time complexity of this process is O(n). At last, the extended method LCE is obtained by using 12 and the complexity is O(n).

The computational complexity of the LCE method is the sum of the two parts above, namely O(\(3n+nlogn\)). Generally speaking, O(3n) is a complexity of linear order and it can simplify to O(n). O(nlogn) refers to a complexity of logarithmic order. Therefore, the complexity of LCE is O(\(n+nlogn\)). Although this complexity is not very low, its precision is better than the other algorithms from the experimental results of the complementary cumulative distribution function, community division, Kendall’s coefficient and spreading influence. In summary, proposed approach can be appropriate for recognition of influential nodes in view of comprehensive analysis of the factors above.

Time complexity, which is determined by program running time and computational cost, is widely used as a reliable evaluation criterion for assessing the performance of algorithms. A higher time complexity indicates excessive computational resource consumption and disadvantages in program operation. In this section, we focus on testing the running effects of all involved algorithms, and have deduced the time complexity of each algorithm based on its core computational logic (e.g., the complexity of LCE is composed of two parts: O(nlogn) for community detection using the Louvain algorithm and O(n) for extended neighbor metric calculation). To clearly present the time complexity characteristics of the proposed Local Community Structure Entropy (LCE) method and the seven comparative algorithms (Degree Centrality (DC), Betweenness Centrality (BC), K-shell decomposition (KS), Chance-Based Centrality (CBC), Community-Based Measure (CBM), Intra-Community Centrality (ICC), and Entropy-Renewal Heuristic (EnRenew)), and to intuitively reflect the differences in computational efficiency between different algorithms, we summarize their core categories (divided according to the scope of network information relied on: Local, Global, Hybrid) and corresponding computational complexity results in Table 8. This table provides a direct basis for the subsequent comparative analysis of the balance between computational efficiency and recognition performance of each algorithm.

Conclusion

The research on the importance of nodes combining topological information with characteristics of community structure is particularly necessary. But the most of methods neglect the consequence brought by surrounding nodes with the same attribute in a community structure, which can give rise to low precision and fail to be appropriate for different datasets. For better effects, in this paper, we propose a novel measure named Local Community Structure Entropy (LCE) to find influential nodes in complex networks. The method fully combines information entropy with the intrinsic community architecture by considering the connecting magnitude of community structure. On the one hand, we segment the network into distinct communities by harnessing the community detection algorithm, and compute the node’s entropy centrality based on nearest neighboring information. On the other hand, we extend to second-order neighbors information and deduce the entropy centrality index. Additionally, we employs seven algorithms including the Degree Centrality (DC), Betweenness Centrality (BC), K-shell decomposition (KS), Chance-Based Centrality (CBC), Community-Based Measure (CBM), Intra-Community Centrality (ICC) and Entropy-Renewal Heuristic (EnRenew) to conduct comparison tests for representing the performance of the proposed method. In the experiments, we adopts a series of indicators, including Susceptible–Infected–Recovered (SIR) model, Kendall’s coefficient, complementary cumulative distribution function, different community division, spreading efficiency and complexity to execute corresponding experiments and evaluate the performance on social and synthetic networks. Results demonstrate that, the proposed method outperforms involved algorithms in the recognition capability and promotes efficiency and universality.

However, it’s imperative to recognize the confines of this study. The applicability of this method to sequential networks and higher-order networks remains to be verified. While the communication influence of nodes is simulated predominantly through a dynamic model, real-world communication processes extend beyond this model’s scope in their multifaceted intricacy. As future avenues beckon, there’s an imperious need to embrace the complexities of real-life communication modalities. Additionally, amalgamating the myriad social and topological attributes of nodes to craft a more holistic appraisal of individual influence emerges as a promising frontier awaiting scholarly exploration.

This study currently focuses on static network topologies, with two key limitations:

1. It does not account for networks’ dynamic evolution (e.g., time-varying connections in social networks or load-driven changes in power grids).

2. It is poorly adapted to dynamic scenarios: when topology changes (e.g., node/edge additions/deletions), the LCE method requires full re-computation of community detection and entropy centrality, lacking real-time/near-real-time updates of influence rankings–making it unsuitable for time-sensitive tasks like real-time public opinion monitoring.

These limitations arise from the study’s core goal: to first validate the core effectiveness of LCE (characterizing node influence via local community entropy) in controlled static settings, laying a baseline for subsequent extensions to dynamic scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arenas, A., & De Domenico, M. Nonlinear dynamics on interconnected networks. Elsevier (2016).

Wandelt, S., Xu, Y. & Sun, X. Measuring node importance in air transportation systems: On the quality of complex network estimations. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 240, 109596 (2023).

Strogatz, S. H. Exploring complex networks. nature 410(6825), 268–276 (2001).

Havlin, S. et al. Challenges in network science: Applications to infrastructures, climate, social systems and economics. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 214, 273–293 (2012).

Goldenberg, J., Libai, B. & Muller, E. Talk of the network: A complex systems look at the underlying process of word-of-mouth. Marketing letters 12, 211–223 (2001).

Tong, T.-C. et al. Mitigation strategy for the cascading failure of complex networks based on node capacity control function. IEEE Access 7, 184743–184758 (2019).

Ma, T., Lan, L., Zong, Y. & Arebi, P. Detection of top-r spreader influential nodes on the social internet of things networks to maximize spreading influence. The European Physical Journal Plus 139(9), 801 (2024).

Xu, G. & Dong, C. Cagm: A communicability-based adaptive gravity model for influential nodes identification in complex networks. Expert Systems with Applications 235, 121154 (2024).

Yang, Q., Wang, Y., Yu, S. & Wang, W. Identifying influential nodes through an improved k-shell iteration factor model. Expert Systems with Applications 238, 122077 (2024).

Tong, T., Yuan, W., Jalili, M., Dong, Q. & Sun, J. A novel ranking approach for identifying crucial spreaders in complex networks based on tanimoto correlation. Expert Systems with Applications 255, 124513 (2024).

Shu, J., Zhan, X., Jiang, G., & Ma, W. Key nodes evaluation in opportunistic networks based on influence between nodes. In China Conference on Wireless Sensor Networks, 3–16 (Springer, 2021).

Zhou, A. & Qian, J. An adaptive method for identifying super nodes from network-wide view. Journal of Network and Systems Management 31(3), 51 (2023).

Freeman, L.C., et al. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social network: critical concepts in sociology. Londres: Routledge 1, 238–263 (2002).

Kitsak, M. et al. Identification of influential spreaders in complex networks. Nature physics 6(11), 888–893 (2010).

Faust, K. Centrality in affiliation networks. Social networks 19(2), 157–191 (1997).

Freeman, L.C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry, 35–41 (1977).

Bonacich, P. Factoring and weighting approaches to status scores and clique identification. Journal of mathematical sociology 2(1), 113–120 (1972).

Brin, S. & Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Computer networks and ISDN systems 30(1–7), 107–117 (1998).

Estrada, E. & Rodriguez-Velazquez, J. A. Subgraph centrality in complex networks. Physical Review E 71(5), 056103 (2005).

Hirsch, J. E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences 102(46), 16569–16572 (2005).

Chen, D., Lü, L., Shang, M.-S., Zhang, Y.-C. & Zhou, T. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks. Physica a: Statistical mechanics and its applications 391(4), 1777–1787 (2012).

Gao, S., Ma, J., Chen, Z., Wang, G. & Xing, C. Ranking the spreading ability of nodes in complex networks based on local structure. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 403, 130–147 (2014).

Zareie, A., Sheikhahmadi, A., Jalili, M. & Fasaei, M. S. K. Finding influential nodes in social networks based on neighborhood correlation coefficient. Knowledge-based systems 194, 105580 (2020).

Yang, J., Lu, J., Wu, Y., Li, T., & Yang, Y. A node ranking method based on local structure information in complex networks. Engineering Letters 30(1) (2022).

Wen, T. & Deng, Y. Identification of influencers in complex networks by local information dimensionality. Information Sciences 512, 549–562 (2020).

Tong, T., et al. A hybrid recognition framework of crucial seed spreaders in complex networks with neighborhood overlap. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems, 1–24 (2024).

Ullah, A. et al. Identification of nodes influence based on global structure model in complex networks. Scientific Reports 11(1), 6173 (2021).

Sabidussi, G. The centrality index of a graph. Psychometrika 31(4), 581–603 (1966).

Liu, Z., Jiang, C., Wang, J. & Yu, H. The node importance in actual complex networks based on a multi-attribute ranking method. Knowledge-Based Systems 84, 56–66 (2015).

Yang, F. et al. Identifying the most influential spreaders in complex networks by an extended local k-shell sum. International Journal of Modern Physics C 28(01), 1750014 (2017).

Namtirtha, A., Dutta, B. & Dutta, A. Semi-global triangular centrality measure for identifying the influential spreaders from undirected complex networks. Expert Systems with Applications 206, 117791 (2022).

Ma, L.-L., Ma, C., Zhang, H.-F. & Wang, B.-H. Identifying influential spreaders in complex networks based on gravity formula. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 451, 205–212 (2016).

Zhang, X., Wang, Z., Liu, G. & Wang, Y. Key node identification in social networks based on topological potential model. Computer Communications 213, 158–168 (2024).

Khanday, A. M. U. D., Wani, M. A., Rabani, S. T. & Khan, Q. R. Hybrid approach for detecting propagandistic community and core node on social networks. Sustainability 15(2), 1249 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Wang, J. & Xu, Y. Research on node influence in complex network based on multi-scale centrality algorithm. Procedia Computer Science 228, 1128–1133 (2023).

Tong, T., Dong, Q., Sun, J. & Jiang, Y. Vital spreaders identification synthesizing cross entropy and information entropy with kshell method. Expert Systems with Applications 224, 119928 (2023).

Meng, L., Xu, G., Yang, P. & Tu, D. A novel potential edge weight method for identifying influential nodes in complex networks based on neighborhood and position. Journal of Computational Science 60, 101591 (2022).

Shang, R., Zhang, W., Zhang, J., Feng, J. & Jiao, L. Local community detection based on higher-order structure and edge information. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 587, 126513 (2022).

Kazemzadeh, F., Safaei, A. A. & Mirzarezaee, M. Influence maximization in social networks using effective community detection. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 598, 127314 (2022).

Hu, Q., et al. A new approach to identify influential spreaders in complex networks. In International Conference on Web-Age Information Management, 99–104 (Springer, 2013).

Kumar, S., Gupta, A. & Khatri, I. Csr: A community based spreaders ranking algorithm for influence maximization in social networks. World wide web 25(6), 2303–2322 (2022).

Bouyer, A., Beni, H. A., Arasteh, B., Aghaee, Z. & Ghanbarzadeh, R. Fip: A fast overlapping community-based influence maximization algorithm using probability coefficient of global diffusion in social networks. Expert systems with applications 213, 118869 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Li, X. & Gan, C. Identifying influential nodes in social networks via community structure and influence distribution difference. Digital Communications and Networks 7(1), 131–139 (2021).

Zhao, Z., Wang, X., Zhang, W. & Zhu, Z. A community-based approach to identifying influential spreaders. Entropy 17(4), 2228–2252 (2015).

Tulu, M. M., Hou, R. & Younas, T. Identifying influential nodes based on community structure to speed up the dissemination of information in complex network. IEEE access 6, 7390–7401 (2018).

Zhao, Z.-J., Guo, Q., Yu, K. & Liu, J.-G. Identifying influential nodes for the networks with community structure. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 551, 123893 (2020).

Guo, C. et al. Influential nodes identification in complex networks via information entropy. Entropy 22(2), 242 (2020).

Wang, H., Yu, S., Zeadally, S., Rawat, D. B. & Gao, Y. Introduction to the special section on network science for internet of things (iot). IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 7(1), 237–238 (2020).

Fortunato, S. Community detection in graphs. Physics reports 486(3–5), 75–174 (2010).

Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M. & Rubin, D. B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the em algorithm. Journal of the royal statistical society: series B (methodological) 39(1), 1–22 (1977).

Girvan, M. & Newman, M. E. Community structure in social and biological networks. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 99(12), 7821–7826 (2002).

Newman, M. E. Fast algorithm for detecting community structure in networks. Physical review E 69(6), 066133 (2004).

Raghavan, U. N., Albert, R. & Kumara, S. Near linear time algorithm to detect community structures in large-scale networks. Physical review E 76(3), 036106 (2007).

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R. & Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of statistical mechanics: theory and experiment 2008(10), 10008 (2008).

Traag, V. A. Faster unfolding of communities: Speeding up the louvain algorithm. Physical Review E 92 (3), 032801 (2015).

Volkenstein, M.V. Entropy and Information; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, (2009).

Castellano, C. & Pastor-Satorras, R. Thresholds for epidemic spreading in networks. Physical review letters 105(21), 218701 (2010).

Zareie, A., Sheikhahmadi, A. & Fatemi, A. Influential nodes ranking in complex networks: An entropy-based approach. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 104, 485–494 (2017).

Yan, G. et al. Spectrum of controlling and observing complex networks. Nature Physics 11(9), 779–786 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Qing Yang for his help in providing the experimental platform.

Funding

This work is not supported by any funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. W wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures. Q. Y and Y. Z reviewed the manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Yang, Q. & Zhu, Y. Measurement of influential nodes in networks based on community structure information entropy. Sci Rep 15, 42756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26986-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26986-y