Abstract

Lingze mixture (LM), a traditional Chinese herbal formula, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in treating gouty arthritis (GA). However, its pharmacological mechanisms remain largely unexplored. This study aimed to conduct an exploratory investigation into the anti-inflammatory effects of LM in a GA rat model and to preliminarily identify potential signaling pathways involved through transcriptome analysis. A rat GA model was induced by monosodium urate (MSU) injection. Animals were treated with LM at low, medium, or high doses, with etoricoxib as a positive control. Synovial inflammation was assessed histologically (H&E staining). Protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC). To generate mechanistic hypotheses, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on synovial tissues from the blank, model, and medium-dose LM groups. LM treatment significantly attenuated MSU-induced synovitis and dose-dependently reduced the protein levels of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB. Transcriptome analysis revealed significant enrichment of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in the model group. Notably, medium-dose LM treatment appeared to modulate these pathways, along with alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism. Our findings confirm the anti-gout efficacy of LM in vivo and provide preliminary evidence suggesting its action may be associated with the modulation of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. This study offers valuable mechanistic clues and a foundation for further in-depth investigation into LM’s mode of action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gouty arthritis (GA) is a common inflammatory arthritis caused by the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints1,2,3. Current treatments (e.g., NSAIDs, colchicine) often have limitations due to side effects4,5. Lingze mixture (LM), derived from classical traditional Chinese medicine formulations, has shown promise in clinical settings for alleviating GA symptoms with fewer adverse effects. Evidence from previous studies, including those published in regional journals not eligible for citation in this context, indicates that LM can attenuate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. This collective body of work forms a foundational background for the current research. The synovial tissue was selected as the primary focus of this study because it is the primary site of MSU crystal deposition and inflammatory response in GA, richly expressing TLR4 and other innate immune receptors central to GA pathogenesis1. The Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway is a crucial mediator of sterile inflammation in GA. While LM’s clinical effect is evident, a comprehensive understanding of its molecular mechanisms is lacking7,8. This study therefore employed an integrated approach, combining animal pharmacodynamic evaluation with transcriptome analysis, to preliminarily explore the anti-inflammatory effects of LM and its potential mechanisms, aiming to provide a basis for subsequent targeted research.

Materials and methods

Animals and ethics

Sixty 2-month old male Wistar rats (180–200 g) were housed under standard conditions (22–26 °C, 50–70% humidity) with free access to food and water. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval no. 2022JH2/101300047) and conducted in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”.

Drug preparation

LM is the addition and subtraction of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction, which is derived from Jingui Yaolue, and composed of nine herbs (Cinnamomum cassia Presl., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Ephedra sinica Stapf., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Zingiber officinale Rosc., Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge., Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. and Aconitum carmichaelii Debx.), and was decocted, filtered, and concentrated to 1 g crude herb/mL. Doses for animal administration were calculated based on clinical human equivalents (70 kg) via body surface area conversion: low-dose (4.1625 g crude herb/kg/day), medium-dose (8.325 g crude herb/kg/day), and high-dose (16.65 g crude herb/kg/day). MSU crystals (Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared and suspended in sterile saline (50 mg/mL). Etoricoxib tablets were ground and suspended in normal saline (0.54 mg/mL).

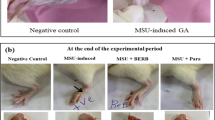

Experimental design and GA model induction

Rats were randomly divided into six groups (n = 10): Blank control, Model, Etoricoxib, LM-Low, LM-Medium, LM-High. Animals received daily gavage of their respective treatments (10 mL/kg) for 5 days prior to MSU injection. On day 5, GA was induced by injecting 0.2 mL of MSU suspension (50 mg/mL) into the right posterior ankle joint of rats in all groups except the Blank group (which received saline). Drug administration continued for 2 days post-injection. Joint swelling was monitored to confirm successful model establishment.

Etoricoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, was chosen as the positive control due to its established efficacy in managing acute gout attacks and its common use in clinical practice as a first-line NSAID. While effective, long-term use of etoricoxib is associated with cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, highlighting the need for safer alternatives like LM4,5.

Tissue collection

On day 8, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg)9. Upon confirmation of deep anesthesia (loss of pedal and corneal reflexes), euthanasia was performed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia, in accordance with AVMA guidelines for euthanasia of laboratory animals10. Ankle joints were collected and fixed for histopathology and IHC analysis. Synovial tissues from knee joints of Blank, Model, and LM-Medium groups (n = 6–10/group) were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for RNA-seq.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Synovial tissues were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for pathological evaluation. For IHC, sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, subjected to antigen retrieval, and incubated with primary antibodies against TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 (Abcam) overnight at 4 °C, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies. Staining was visualized using a DAB kit. Images were captured under a light microscope, and protein expression was quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software by measuring integrated optical density (IOD) in three non-repetitive fields per sample.

RNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Total RNA was extracted from synovial tissues. Library construction and sequencing (Illumina platform) were performed by Shanghai Baiqu Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. Quality control was performed on raw data. Clean reads were aligned to the rat reference genome (Rn6). Gene expression levels were quantified as FPKM. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between groups were identified using the DESeq2 package with thresholds of |log2(Fold Change)| > 1 and False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses of DEGs were performed using clusterProfiler R package.

Statistical analysis

Data from IHC quantification are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

LM ameliorates synovial inflammation in GA rats

Histopathological evaluation by H&E staining revealed a normal synovial structure with no signs of inflammation in the Blank group (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the Model group exhibited severe synovitis, characterized by pronounced synovial cell hyperplasia, tissue disorganization, and massive infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 1B). These pathological changes were ameliorated by treatment with etoricoxib (Fig. 1C) and all doses of LM (Fig. 1D, E, F). The high-dose LM group showed the most significant improvement, with markedly reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and a synovial architecture that most closely resembled the normal state (Fig. 1F).

LM inhibits TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB protein expression

IHC analysis showed minimal positive staining for TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB in the synovium of Blank group rats. Their expression was significantly upregulated in the Model group (P < 0.01). LM treatment dose-dependently downregulated the expression of these proteins. The effect of high-dose LM was comparable to that of etoricoxib (Figs. 2 and 3).

Immunohistochemical staining of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 in the synovial tissues of the ankle joints of rats across groups (×200). Brown-yellow staining in dicates positive expression. Scale bar: 100 μm. A: Blank control group (n = 10); B: Model control group (n = 10); C: Etoricoxib group (n = 10); D: Low-dose LM group (n = 10); E: Medium-dose LM group (n = 10); F: High-dose LM group (n = 10).

Effects of LM on the expression levels of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 in the synovial tissues quantified by immunohistochemistry. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 10 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Model group; ##P < 0.01 vs. Blank control group (by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test). A: Blank control group; B: Model control group; C: Etoricoxib group; D: Low-dose LM group; E: Medium-dose LM group; F: High-dose LM group.

Transcriptomic profiling reveals pathway modulation

RNA-seq analysis identified 47 DEGs (38 upregulated, 9 downregulated) between the Model and Blank groups. KEGG enrichment analysis of these DEGs highlighted significant involvement of the “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway”, “NF-kappa B signaling pathway”, “MAPK signaling pathway”, and “Phagosome”. Comparing the LM-Medium group to the Model group revealed 64 DEGs (3 upregulated, 61 downregulated). Enriched pathways for these DEGs included the “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway”, “NF-kappa B signaling pathway”, “MAPK signaling pathway”, and “Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism” (Figs. 4 and 5), suggesting a potential regulatory role of LM in these processes.

GO analysis of biological functions

GO analysis indicated that DEGs in the Model group (vs. Blank) were primarily involved in biological processes such as inflammatory response, signal transduction, and regulation of membrane potential. Cellular components included plasma membrane and synapse. Molecular functions included transmembrane signaling receptor activity and ion channel activity. After LM treatment (LM-Medium vs. Model), the biological processes of DEGs were enriched in monoatomic ion transport and transmembrane regulation (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The pathogenesis and systemic implications of gouty arthritis

GA is characterized by dysregulation of purine metabolism and/or abnormal excretion of uric acid and subsequent increased serum concentrations, leading to the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in the joint capsule, bursa, cartilage, and kidneys, resulting in lesion formation and inflammatory reactions11. GA has been linked to hypertension, depression, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, insulin resistance, kidney disease, inflammation, the severity of infectious diseases, tumor lysis syndrome, menopausal syndrome, organ transplant complications, and other diseases, such as obstructive sleep apnea and primary Sjogren’s syndrome2. Intake of dietary purines can increase the risk of hyperuricemia and GA, which have exhibited an increased annual prevalence in relatively younger patients1. Repeated attacks of GA can cause joint deformity and damage renal function, adversely affecting the quality of life of patients12.

The role of cytokine signaling and the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway in acute gout attack

Increased serum concentrations of uric acid can lead to acute attacks of GA, which are regulated by various cytokines and signaling pathways throughout the process. Supersaturated MSU crystals are precipitated in the blood and deposited in the joints, tendons, and surrounding soft tissues13,14. MSU crystals chemoattract leukocytes, which release a variety of inflammatory mediators, resulting in local inflammatory responses. The initiation of inflammation is mainly recognized by related molecular patterns through pattern recognition receptors, which then initiate defense mechanisms and the release of inflammatory mediators15,16. Activation of the inflammatory factor IL-1β will cause the recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, and the release of various inflammatory mediators, which amplify the inflammatory cascade. The release of inflammatory cytokines can mediate the characteristic symptoms of acute GA, such as pain, fever, redness, and swelling17,18. TLRs are an important family of receptors involved in the first line of defense against microbes. Recent studies have reported that the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway plays important roles in the pathogenesis and treatment of various diseases19,20.

Rationale for investigating LM

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, and glucocorticoids are commonly used for treatment of acute GA. However, due to adverse reactions, such as digestive system damage and liver and kidney toxicity, the clinical application of this regimen is limited. Traditional Chinese medicine is reported to have a significant curative effect with few side effects for treatment of GA21,22. LM is the addition and subtraction of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction, which is derived from Jingui Yaolue, and composed of nine herbs (Cinnamomum cassia Presl., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Ephedra sinica Stapf., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz.,Zingiber officinale Rosc., Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge., Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. and Aconitum carmichaelii Debx.). The effects of LM include “expelling wind”, “removing dampness”, “dredging arthralgia”, “dispersing cold”, and “clearing heat”. Clinically, LM has been shown to effectively alleviate acute exacerbation of GA. The Department of Rheumatology of our hospital has extensive clinical experience in the treatment of GA and other rheumatic diseases. Previous studies have confirmed that LM not only has anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and detumescence effects in patients with GA, but can also reduce blood uric acid levels. In addition, animal studies have reported that LM is effective for the prevention and treatment of GA by altering the expression profiles of inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6.

Synopsis of efficacy, preliminary mechanisms, and future research directions for LM

This study primarily serves as an exploratory investigation, confirming the significant efficacy of LM in alleviating GA in an animal model and providing preliminary multi-omics clues for its potential mechanisms.

Confirmation of pharmacodynamic effects

Our histopathological results robustly demonstrate that LM can dose-dependently improve synovitis, reducing inflammatory cell infiltration and synovial tissue damage in GA rats. This confirms the anti-inflammatory and protective effects of LM observed in previous clinical and pharmacological studies, providing a solid foundation for its further mechanistic study.

Preliminary mechanistic

Clues from Protein and Transcriptome Levels The IHC results clearly show that LM inhibits the activation of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, a core pathway driving NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production in GA23. Transcriptome sequencing further suggests that LM’s effects may extend to modulating the MAPK signaling pathway and amino acid (alanine, aspartate, glutamate) metabolism24. The downregulation of a large number of genes (61 out of 64 DEGs were downregulated by LM) hints at a broad anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect, consistent with the multi-component, multi-target characteristics of traditional Chinese medicine formulations. These findings should be regarded as valuable associative clues rather than definitive proof of mechanism.

Limitations and future perspectives

The main limitation of this study is its exploratory and correlative nature.The proposed mechanism based on differential gene enrichment requires extensive experimental validation. Future work should include25,27,27: (1) Using specific pathway inhibitors (e.g., TAK-242 for TLR4) or gene knockout animals to verify the necessity of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway in mediating LM’s effects; (2) Measuring changes in key inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) in joint fluid or serum to functionally link pathway inhibition to cytokine production; (3) Isolating and quantifying active compounds from LM (e.g., berberine, paeoniflorin, astragalosides) and studying their interactions and targets using network pharmacology and molecular docking approaches to explain the multi-target effects; (4) Further investigating the potential role of LM in regulating urate metabolism and transporters (e.g., URAT1, ABCG2), which was beyond the scope of this initial study.

In conclusion, this study successfully transitions from observing the efficacy of LM to proposing a testable mechanistic hypothesis. We have preliminary established an association between LM’s anti-GA effect and the inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, offering clear direction and a solid foundation for subsequent in-depth mechanistic research.

Conclusion

LM effectively alleviates gouty arthritis in a rat model.Integrated analysis of immunohistochemistry and transcriptome data suggests that its mechanism may be related to the inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway and modulation of MAPK signaling and amino acid metabolism. These findings provide preliminary mechanistic insights and a basis for the further development and in-depth studies of LM.

Data availability

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) included within the article.

References

Dalbeth, N., Merriman, T. R. & Stamp, L. K. Gout[J] Lancet ; 388(10055): 2039–2052. (2016).

Rock, K. L., Kataoka, H. & Lai, J. J. Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9 (1), 13–23 (2013).

Keller, S. F. & Mandell, B. F. Management and cure of gouty arthritis. Med. Clin. North. Am. 105 (2), 297–310 (2021).

Clebak, K. T., Morrison, A., Croad, J. R. & Gout Rapid Evid. Rev. Am. Fam Physician ; 102(9):533–538. (2020).

Richette, P. et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for gout management. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 (1), 29–42 (2017).

Weaver, J. S. et al. Gouty arthropathy: review of clinical manifestations and Treatment, with emphasis on imaging. J. Clin. Med. 11 (1), 166 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. MiR-146a alleviates inflammation of acute gouty arthritis rats through TLR4/MyD88 signal transduction pathway[J]. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23(21), 9230-9237 (2019).

Sun, X. et al. Isovitexin alleviates acute gouty arthritis in rats by inhibiting inflammation via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway[J]. Pharm. Biol. 59 (1), 1324–1331 (2021).

National Research Council (US) Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (National Academies Press (US), 2003).

Leary, S. et al. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Gout and diet: A comprehensive review of mechanisms and management. Nutrients 14 (17), 3525 (2022).

Pascart, T. & Lioté Gout: state of the Art after a decade of developments[J]. Rheumatology(Oxford) 58 (1), 27–44 (2019).

Amaral, F. A. et al. Transmembrane TNF-α is sufficient for articular inflammation and hypernociception in a mouse model of gout[J]. Eur. J. Immunol. 46 (1), 204–211 (2016).

Zha, X. et al. Combination of uric acid and pro-inflammatory cytokines in discriminating patients with gout from healthy controls[J]. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 1413–1420 (2022).

Qing, Y. F. et al. Changes in toll like receptor (TLR) 4-NF-κB-IL-1β signaling in male gout patients might be involved in the pathogenesis of primary gouty arthritis[J]. Rheumatol. Int. 34 (2), 213–220 (2014).

Ouyang, X. et al. Active flavonoids from lagotis brachystachya attenuate monosodium urate-induced gouty arthritis via inhibiting TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway and NLRP3 expression. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 760331 (2021).

Kawai, T. & Akira, S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with otherinnate receptors in infection and immunity[J]. Immunity 34(5), 637-50 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. Role of TLR4/NF-κB pathway for early change of synovial membrane in knee osteoarthritis rats[J]. China J. Orthop. Trauma. 32 (1), 68–71 (2019).

Shen, R., Ma, L. & Zheng, Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of Luteolin on acute gouty arthritis rats via TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 45 (2), 115–122 (2020).

Huang, Q. et al. HSP60 regulates monosodium urate crystal-induced inflammation by activating the TLR4-NF-κB-MyD88 signaling pathway and disrupting mitochondrial function. Oxid Med Cell Longev. ; 2020:8706898. (2020).

Wang, X. & Wang, Y. G. Progress in treatment of gout using Chinese and Western medicine[J]. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 26 (1), 8–13 (2020).

Mbuyi, N. & Hood, C. An update on gout diagnosis and management for the primary care provider[J]. Nurse Pract. 45 (10), 16–25 (2020).

So, A., Dumusc, A. & Nasi, S. The role of IL-1 in gout: from bench to bedside. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 57 (1), 112–119 (2018).

Wishart, D. S. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 (7), 473–484 (2016).

Ru, J. et al. TCMSP: a database of systems Pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 6, 13 (2014).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (W1), W357–W364 (2019).

Li, S. & Zhang, B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: theory, methodology and application. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 11 (2), 110–120 (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by Liaoning Science and Technology Plan Project [grant numbers 2022JH2/101300047]; Second Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine [grant number 2023-LZYY-1-04].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu J: analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.Liu J and Kong DH designed and performed most of the experimentsMa BD, Chen YS and Zhao Y: conceived and supervised the research.Gan Y, Qiao M, Bao YL, Fang XN, Zhu JH, Ming CR: provided the technical advice. Wei HH, Yang DW, Han C, Gao ZP and Wang HY: participated in performing the experiments.Everyone contributed to the writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2022JH2/101300047) and conducted in strict accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”, and this study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Chen, Y., Zhao, Y. et al. Exploratory study on the efficacy of Lingze mixture in gouty arthritis rats and preliminary analysis of its potential mechanisms via transcriptome sequencing. Sci Rep 15, 42873 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27028-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27028-3