Abstract

Low-disturbance excavation constitutes a critical technology for rock mass engineering in environmentally sensitive areas, exerting decisive impacts on environmental protection and construction efficiency. This study employs a combined methodology incorporating small-scale model tests, field measurements, and numerical simulations to systematically investigate multi-parameter borehole layout schemes in limestone strata. Through PVDF piezoelectric sensors installed on small-scale model borehole walls, this research precisely captured the dynamic borehole wall forces during high-pressure gas expansion for the first time, establishing reliable design parameters with peak expansion tube forces reaching 581 MPa and validating its hard rock fracturing capability. The field-calibrated FLAC3D numerical model systematically compared the dynamic response patterns of rock mass plastic zone and near-field vibrations to three controlling parameters: burial depth, horizontal borehole spacing, and expansion tube density, identifying the optimal parameter combination of horizontal borehole spacing at 1.5 m × 2.0 m and a borehole depth of 1.5 m (burial depth of 1.3 m). Field application has verified that this optimized drilling pattern significantly enhances hard rock fragmentation efficiency, induces dense fracture networks, and substantially reduces mechanical rock-breaking losses.

Similar content being viewed by others

introduction

The vibrations generated during the rock-breaking process represent a significant safety factor that can potentially impact the structural reliability of existing buildings in the surrounding area. With the expansion of infrastructure development across various countries, there has been a notable increase in construction projects in environmentally sensitive locations. Consequently, the engineering community has placed a growing emphasis on the development of low-disturbance, safe, and efficient rock-breaking solutions in these areas1,2. The current research on rock excavation in environmentally sensitive areas is primarily focused on urban metro projects, adjacent buried oil and gas pipelines, high-voltage power towers and adjacent structures3,4,5,6. Although dynamite blasting is one of the most prominent methods for rock fragmentation, it is often challenging to meet the high demand for vibration control7,8, particularly in densely populated and environmentally sensitive areas where applications are subject to numerous limitations. In order to ensure safety standards can be met, rock excavation work is frequently conducted using non-blasting techniques in regions where high vibration levels are required9,10. However, the characteristics of the rock exert a significant influence on the efficacy of mechanical and other non-blasting rock broken techniques, particularly in high strength and abrasion resistant rock conditions11. Consequently, alternative rock-breaking techniques are employed in environmentally sensitive locations to assist with mechanical excavation. These include carbon dioxide phase change fracturing, Silent Chemical Demolition Agent (SCDA), and high-voltage pulse fragmentation, etc.

The CO₂ phase change rock-breaking method is based on the transformation of CO₂ from a liquid to a gas within a short period of time. This transformation can result in a volume expansion of more than 600 times the original liquid volume12,13. Nevertheless, the high cost of manufacturing expansion tubes and the absence of established production standards present significant challenges to the promotion of large-scale applications14. SCDA are composed of calcium oxide, silicates, and organic and inorganic additives. Upon reaction with water, the formation of calcium hydroxide results in a significant increase in volume and pressure15,16,17. While this method effectively controls vibration and noise, the prolonged response time impairs construction efficiency. High-voltage pulse fragmentation is the utilization of plasma channels generated by electrodes in a rock or liquid medium to thermally expand and excite shock stress waves, thereby causing rock fragmentation18,19. Nevertheless, this rock-breaking scheme has considerable requirements for equipment and a power supply, as well as high energy consumption and costs.

The High-Pressure Gas Expansion Method (HPGEM) is a low-disturbance, safe, and efficient rock fragmentation technique. This method primarily utilizes the ignition of solid expansion agent within an expansion tube, which rapidly produce a large volume of gas in a short time. The instantaneous expansion pressure induces cracking within the rock mass. Overall, HPGEM achieves significantly shorter rock-breaking durations compared with SCDA, and its expansion tube preparation and cost are considerably more advantageous than those of CO₂ phase-transition fracturing, making it more suitable for engineering applications. Liu D W et al.20 employed HPGEM in rock-breaking operations within urban small-section hard rock tunnels. They combined theoretical calculations and field tests to conclude that this method was superior to traditional dynamite blasting in terms of rock-breaking efficiency and vibration hazards. Furthermore, they evaluated the safety of excavation construction by HPGEM for underground liaison channel by combining cloud modelling theory21. Zhang Q et al.22 combined model experiments and numerical simulations to study the fracturing effect of instantaneous expander that can form a single crack. It is found that instantaneous expander can effectively guide the crack direction and can replace explosives for directional roof cutting with higher safety and more convenient operation.

Despite the extensive research conducted by numerous scholars on the fracturing mechanism of HPGEM, employing a combination of model tests and numerical simulations23,24, the field remains in a state where practical applications have advanced further than theoretical understanding. In numerical simulations of high-pressure gas expansion and the force exerted on the borehole wall, the majority of studies are based on the derivation of the explosive blast gas formula25,26. The rock-breaking method through gas expansion is also subject to variations in the fracture effects of rock as a result of differences in the growth rates and final volumes of the various gases involved. Zhang Y et al.27 conducted a simulation on the rock fracturing situation induced by stress waves with diverse loading rates that arose from the phase change of liquid carbon dioxide. The research findings demonstrated that while an elevated loading rate of the stress wave tended to facilitate the formation of a crushed zone in the vicinity of the holes, the propagation of cracks would be restrained. To ascertain the impact pressure generated during the gas expansion process, numerous scholars have elected to install pressure sensors on and in close proximity to the expansion tubes, thereby facilitating precise monitoring of the pressure data28,29,30.

In urban areas, the excavation of shafts is frequently constrained by the presence of narrow confines and the necessity for low-disturbance operations. This renders the utilization of substantial machinery and drill-and-blast techniques challenging. Similarly, numerous constraints are imposed by field trials in environmentally sensitive zones, many of which are contingent upon regulatory approvals and the presence of various uncertainties. Accordingly, in order to examine the impact of HPGEM utilization at shallow depths on the surrounding environment, rock-breaking experiments of an identical scale were conducted in a quarry in Hunan, China. Concurrently, in order to achieve the greatest possible restoration of the expansion tube’s force on the borehole wall within the rock mass in the simulation, an small-scale model is designed to test the pressure on the borehole wall throughout the expansion process. The model was calibrated via field tests and simulations of different hole layout patterns in the shallow surface. This served to provide a basis for the construction work of this technology under the conditions of the shallow surface and in environmentally sensitive areas.

High-pressure gas expansion method

Expansion tubes

The design of expansion tubes exhibits a degree of variability, contingent upon the specific rock-breaking requirements that they are intended to fulfil. With regard to directional cutting in the context of mining, Zhang Q. et al.31 devised the instantaneous expansion with a single fracture, which is capable of generating a single fracture surface instantaneously. The expansion tubes that were previously employed in the context of tunnel boring comprised a gas generator, an ignition head, a wire, a PVC pipe and a cap32. The test utilized a more simplified expansion tube configuration depicted in Fig. 1, which is more suitable for practical engineering applications.

As shown in Fig. 1a, the expansion tube in this experiment consists of a cylindrical polyethylene bag (container), an ignition head, expansion agent and wires. Different sizes of polyethylene bags can be selected to adjust the fracturing effect for different rock strengths and engineering needs. In this experiment, the expansion agent employed is a mixture of two powders, a gas-producing agent and a combustion aid agent, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Neither substance is ignited when exposed to a separate fugitive environment, nor is it initiated by a sudden impact when combined. Depending on the size of the expansion tube, one or more ignition heads are inserted at appropriate locations selected during the expansion agent filling process, as in Fig. 1c. As the process of gas generation is very rapid once the expansion agent has been triggered, the polythene bag is only used as a moisture barrier and to hold the expansion agent. Therefore, once the expansion tube has been filled with sufficient expansion agent, it is simply sealed with tape. During the rock fragmentation process, the primary gas generated is carbon dioxide. If incomplete combustion occurs due to insufficient combustion aid agent or uneven mixing of expansion agent, carbon monoxide may result.

Principles of fracturing

HPGEM primarily utilizes an expansion agent to rapidly release a substantial amount of high-pressure gas, which then acts as a ‘gas wedge’ to facilitate the continuous expansion of cracks, ultimately fracturing the rock body. The process of rock breaking is dependent on the action of high-pressure gas on the borehole wall, therefore, the sealing of the area where the expansion tube is located is of critical importance. In the majority of cases, when the length of the plugging section is sufficiently long, it is sufficient to plug the hole with gravel or quick-drying cement. However, in instances where the length of the plugging section is limited, the use of specialized plugging devices is necessary to prevent punching. In the confined space of the fracturing hole, the gas pressure increases rapidly, forming a high-pressure gas jet that acts around the wall of the fracturing hole and creates a compressive stress field, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The internal compressive stress in the rock body in the vicinity of the fracturing hole is significantly greater than the ultimate compressive strength of the rock, resulting in the rock being compressed and fractured. Once a fissure has formed in the rock body, the fissure wall is subjected to the same compressive stress as the pore wall. This causes the rock body to rupture rapidly under the action of tensile stress. In contrast to stress waves, the compressive stress generated by high-pressure gas acts continuously on the fractures, thereby promoting their expansion. The extent of crack extension during rock breaking is dependent upon a number of factors, including gas pressure, crack dimensions and configuration, and the direction of the jet33,34.

Experiments and result

Rock mechanics tests

The test was conducted in a limestone formation quarry in Hunan Province, China. An open space within the quarry, comprising flat rock devoid of any readily apparent fissures, was selected for the test. Limestone is a common construction material, but it is brittle and prone to fracturing during the mining process. The specimens were subjected to uniaxial compressive testing and Brazilian splitting experiments in the laboratory using an Instron 1342 electro-hydraulic servo universal testing machine, following the sampling of the limestone in the field and subsequent analysis. The failure modes of the samples are illustrated in Fig. 3, and the stress–strain curves were generated by aggregating the data (Fig. 4).

The mean compressive strength of the rock obtained from the test was 101.44 MPa, the mean tensile strength was 9.18 MPa, and the modulus of elasticity was 28.1 GPa. Accordingly, based on prior experience, the gas-producing agent and the booster agent were configured in a 1:1 ratio, with a loading length of 50 cm and a plugging length of 250 cm.

Field experiment

In order to investigate the vibration effect of HPGEM at shallow ground surfaces, the rock-breaking effect of different numbers of expansion tubes in the form of a conventional borehole arrangement is tested. The configuration parameters are presented in Table 1.

In Tests 1 and 2, the fracturing holes were drilled to a depth of 3 m at an angle of 60° to the ground, with a Y-direction of 1.00 m at the bottom of the holes and a spacing of 4.00 m at the top of the holes. In Tests 3 and 4, the fracturing holes were arranged in two rows, comprising the same fracturing holes as those used in Tests 1 and 2. These were positioned in parallel, with a X-direction of 3.00 m. The specific layout of the tests is illustrated in Fig. 5.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the position of the fracturing hole is indicated by a red marker. Once the expansion tubes had been plugged into the base of the holes, the fracturing holes were then filled with limestone fine sand, produced on site from the boreholes. No mechanical assistance was employed for the purposes of loading or compaction throughout the process.

In areas of the shallow surface that are more susceptible to vibration, there are frequently vital structures situated in the immediate vicinity of the seismic source. Accordingly, Nubox-8016 blasting vibration testers were positioned at 10 m, 20 m and 30 m distances from the rock-breaking area, monitoring the vibration during the rock-breaking process. During the test, the vibrometer probe was affixed to the intact rock using plaster, and the vibrometer was configured to be automatically triggered with a trigger level of 0.01 V.

Small-scale model experiment

While the diameter of the fracturing holes and the expansion tube charge in the experiments are comparable to those of actual engineering applications, the direct acquisition of data for such large sizes remains challenging. In particular, the utilization of the NUXI-1008 integrated high-speed data acquisition instrument for piezoelectric signal acquisition is hindered by two key limitations: When the device is situated at a safe distance during the testing phase, the recorded data exhibit a high degree of divergence, which can be attributed to the extended transmission line of the device. When the device is positioned relatively close during the testing phase, it will be damaged by the cracking process. Accordingly, in order to obtain the forces acting on the fracturing hole wall in the actual project, a small-sized equivalent model was designed for measurement (Fig. 6). In addition, since the primary purpose of conducting the small-scale model experiment was to obtain the peak pressure exerted by the expansion tube on the borehole wall, it was considered sufficient to ensure geometric similarity alone, provided that the model strength was maintained. The specific material parameters of the model are shown in the Table 2.

As illustrated in the figure, the concrete model employed by our research for the HPGEM directional fracturing study was utilized as a small-scale model for the hole wall pressure test. In the poured concrete model, the diameter of the fracturing hole was 40 mm, with a depth of 400 mm. Since the force acting on the hole wall is related to the internal pressure P of the fracturing hole, it is necessary to ensure that the ratio of the gas production volume \({\text{V}}_{\text{a}}\) of the expansion tube to the volume V of the fracturing hole space in the small-scale model is equal to that of the original size. The model parameters that correspond to the specified requirements can determined through the application of the following equations:

where ρ denotes the density of the gas-producing agent, c denotes the volume of gas produced per unit mass of the gas-producing agent at ambient temperature and pressure, l denotes the length of the expansion tube,\({d}_{1}\),\({d}_{2}\) denote the diameters of the expansion tubes under the original size and the small-scale model, and \({D}_{1}\),\({D}_{2}\) denote the diameters of the fracturing holes under the original size and the small-scale model. Accordingly, in this small-scale model, when the diameter of the expansion tube employed is 36 mm, it is possible to obtain a time course curve of the hole wall pressure that is identical to that of the original size. Furthermore, the 120 mm charge length is sufficient for rock breaking and ensures the effective length of plugging the hole.

Fracturing pressure measurement

The gas production characteristics of different expansion agents vary, including the rate and volume of gas production, which directly result in disparate effects on the pore wall during the expansion process. Given that the rock body exhibits disparate properties in response to varying loading rates, it follows that the rock-breaking effect of different gas expanders also varies. As the rock mass exhibits disparate properties in response to varying loading rates35,36,37, the rock-breaking effect of different gas expanders also varies. In order to calibrate the expansion agent utilized for the experiments, a piezoelectric polymer-type sensor (PVDF) was employed to obtain the pressure change curve of the pore wall throughout the fracturing process. As with the hole wall pressure test for explosives blasting38,39, the sensing element and the corresponding signal transmission device are situated in the charge hole in close proximity to the expansion tube, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the test system comprises three principal components: piezoelectric signal acquisition, an external circuit, and the requisite test equipment. In the process of acquiring piezoelectric signals, it is challenging to position the PVDF sensor directly on the wall of the hole due to the limitations imposed by the depth and diameter of the fracturing hole. In light of the aforementioned constraints, the PVDF was affixed to an aluminum foil, and an appropriate quantity of marble glue was uniformly distributed over the adhered surface. Subsequently, the aluminum foil was employed to displace the PVDF to the bottom of the hole, thereby securing its attachment to the hole wall and facilitating the acquisition of piezoelectric signals under conditions of limited aperture.

The application of a dynamic impact force to the surface of a PVDF piezoelectric film results in deformation of the film, which in turn causes the initial arrangement of the dipoles to be altered. At this point, the bound charges are released, resulting in a readjustment of the film surface potential. In this case, if an external circuit is connected, a loop current is formed40. In the experiment, the current mode is used for testing, in which two shunt resistors in parallel (\({\text{R}}_{\text{c}}=50\Omega\)) are employed. As the PVDF piezoelectric film can be equated to the charge source Q, the internal resistance \({\text{R}}_{\text{a}}\), capacitance \({\text{C}}_{\text{a}}\), which are connected in parallel. Furthermore, since the internal resistance \({\text{R}}_{\text{a}}\) is of the order of \({10}^{12}\Omega\), it can be regarded as a broken circuit and its influence on the test signal can be ignored. It can thus be posited that the electrical signals captured at the extremities of the resistor are an exact reflection of the charge generated by the PVDF sensor41:

where \(\text{P}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the pressure acting on the PVDF manometer; \(\text{Q}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the charge generated by the PVDF vacuum gauge; A is the effective area of the PVDF, K is the sensitivity coefficient of the PVDF, \({\text{R}}_{\text{c}}\) is the value of the shunt resistor, \(\text{I}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the current through the shunt resistor, \(\text{V}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the voltage across the shunt resistor, and t is the time variable.

Subsequently, the NUXI-1008 integrated high-speed data acquisition instrument records the curve of the voltage signal over time and displays it on an external monitor.

Analysis of test results

Small-scale model experiment results

Experimental observations revealed that the NUXI-1008 integrated high-speed data acquisition system exhibits signal loss or excessive noise during data collection when using extended cables, potentially attributable to resistive attenuation characteristics and electromagnetic compatibility degradation in transmission lines. To mitigate external interference, shortening the cable length (i.e., minimizing the distance between the instrument and the small-scale model) is recommended. Research on the blasting effects under restricted free-face conditions of geotechnical mass indicates that open free-face scenarios, characterized by unconstrained lateral boundaries, may trigger high-speed ejection of fractured rock fragments when applied energy exceeds a critical threshold, posing risks to adjacent structures42,43. For instrument safety, based on fracture propagation and debris ejection patterns observed in prior tests, the acquisition system was positioned 1 m away from the small-scale model, as illustrated in Fig. 8a.

As shown in Fig. 8b, upon triggering the expansion tube, the small-scale model fractured along the predetermined plane, producing a clean fracture surface without impacting instruments positioned on the non-fragmentation ejection face. The NUXI-1008 integrated high-speed data collector was employed to gather the signals and the resulting curves of charge and pore wall pressure over time are presented in Fig. 9a.

As shown in the Fig. 9b, the duration of the sharp pressure change recorded by the PVDF piezoelectric sensor is approximately 0.00175 s. After the expansion tube is triggered, the pressure within the hole rapidly rises to a peak value and then remains relatively stable. That is, the pressure–time history only exhibits a pressure increase phase without a pressure decrease phase. This may be due to the rupture and failure of the insulation backing film of PVDF under long-term loading44. The charges deposited on both sides of the piezoelectric film do not discharge through the measurement circuit, which is manifested in the pressure–time history without a decreasing stage. Therefore, in the obtained pressure–time curve, the peak pressure and the preceding data are reliable39. Specifically, when this expansion agent is in the case of a 1:1 ratio of gas-producing agent to combustion aid agent, the peak pressure reaches 581.4 MPa. For the stage after the peak pressure point, its pressure relief rate shows a lag compared to that of explosive blasting. Consequently, the post-peak part can be approximately regarded as a linear function with a relatively low decreasing rate.

Distribution of surface fissures

In the fracturing tests 1 and 2 where two fracturing holes were arranged, no punching phenomenon occurred. After the expansion tubes were triggered, no vibration was felt at the detonation point 100 m away. During the entire fracturing process, the ground debris moved due to vibration, but there was no flying debris or dust. The noise generated by rock fracturing was relatively low and had no impact on the surrounding environment. Obvious fractures appeared around the two tests, but with relatively poor continuity and fracture widths ranging from 1 to 3 mm, as shown in Fig. 10a.

The experiment involving two fracturing holes revealed that the fracture development was not significant, with the majority of fractures measuring less than 2 mm in width and not exceeding 30 cm in length. In contrast, the experiment with four fracturing holes demonstrated a markedly longer fracture length, attributable to the greater energy generation (see Fig. 10b). By marking the locations of the cracks, the area of the fractured region was approximately 10.5 m2 in Test 3 and about 9.5 m2 in Test 4.

As depicted in Fig. 11, the crack regions generated in the four fracturing hole tests do not exhibit a similar shape. In comparison with Test 3, the crack region in Test 4 shows a deviation from the area of the fracturing hole. This is attributable to the fact that the expansion tubes employed in this experiment lack the function of directional fracturing. The direction in which fractures occur is related to the weak portions of the rock. During rock fracturing of HPGEM, the generation of fractures mainly relies on the high-pressure gas produced by the expansion tubes. These high-pressure gases form a quasi-static high-pressure stress field within the fracturing holes, which acts on the fissures, facilitating the development of micro-fissures into macroscopic fractures until the rock is fractured. Consequently, the joints present in the rock mass and the fissures generated during drilling all serve as significant factors influencing the direction of fracture formation.

Results of vibration tests

Previous studies have demonstrated that HPGEM for rock fragmentation exhibits significant technical advantages over traditional explosive blasting. Under equivalent explosive charge conditions, vibration levels induced by HPGEM range from 21.3% to 42.9% of those generated by conventional explosive methods45. The vibration data collected by the testing instruments during the four high-pressure gas expansion rock-breaking tests were collated and the monitoring results are presented in Table 3.

An increment in the number of fracturing holes leads to a higher energy density in the rock fracturing area, thereby causing an increase in the PPV at the same detection distance. At detection distances of 10 m, 20 m, and 30 m, the PPV values generated by four fracturing holes are consistently greater than those of two fracturing holes. Furthermore, in a manner analogous to the attenuation of shock waves generated by blasting in proportion to the square root of the relative distance46, within the interval from 10 to 20 m, the decreasing amplitude of the peak particle velocity (PPV) is markedly more pronounced than that within the interval from 20 to 30 m.

Numerical modelling and calibration

Model construction

In the modeling of the dynamic response of rocks, there are numerous methods, such as the Finite Element Method (FEM), the Cohesive Element Method (CEM), the Discrete Element Method (DEM), and the Peri Dynamics Method (PDM). In dynamic calculations, FLAC3D employs the explicit Lagrangian difference method. Through nonlinear calculation methods, it can clearly simulate the entire process of materials transitioning from the elastic stage to the plastic stage and ultimately to failure under dynamic loads. Additionally, while each approach has unique strengths, computational efficiency is crucial for large-scale geotechnical problems. In this context, FLAC3D excels due to its ability to efficiently simulate displacement and stress distribution induced by HPGEM.

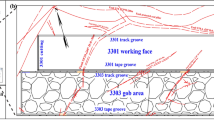

In constructing the simulation model, the limestone formation was assumed to be a homogeneous and isotropic structure. The numerical model dimensions were set to 40 m in length, 20 m in width, and 10 m in height. The borehole diameter was specified as 0.9 m, with a length of 3 m and an inclination angle of 60° relative to the horizontal surface. For the simulation of the four-borehole experiment, the spacing was set to 4 m along the y-axis and 3 m along the x-axis. In terms of boundary condition settings, conventional fixed constraint boundaries were applied. Moreover, since the distance between the boundary and the outermost fracturing hole in the measurement direction exceeds five times the distance-y value, it is sufficient to ensure that reflected waves do not affect the measurement points within the analysis period (Fig. 12).

Following a mesh sensitivity analysis, the maximum mesh size in regions outside the fracture hole’s influence zone was set to 0.4 m. In areas near the fracture hole, where the geometry exhibits greater curvature, a smaller cell size was used to better capture the geometry and accurately simulate stress variations.

Model materials and parameters

In the experiments, surrounding gravel and fine sand from the boreholes were used as plugging materials. The mechanical parameters for this region were defined based on those of typical sandy gravel soil. The mechanical properties of the limestone, determined through laboratory tests, were then input to define the rock parameters (Table 4).

After the expansion tube is triggered, the particles of the gas-producing agent are rapidly burned off and converted into a gas. In this process, the high-pressure gas jet initially interacts with the air layer situated between the expansion tube and the fracturing hole. This interaction results in the significant disturbance of the air layer, leading to the formation of a shock wave. Furthermore, a multi-media flow field is generated through the mixing of the high-temperature and high-pressure gas produced by the gas producing agent with the normal-temperature and normal-pressure air. The interaction mechanism of the multi-loaded multi-media flow field formed inside the fracturing hole, such as shock waves and multi-media flow field, is very complex, and the action of each component is difficult to monitor and reproduce in numerical simulations.

This process can be simplified as a time-dependent compressive stress curve recorded by the PVDF piezoelectric sensor positioned inside the hole. The high-pressure gas force within the rock mass initially rises sharply to a certain value, followed by a gradual increase to its peak, before releasing pressure at a relatively slow rate47, as illustrated in Fig. 13.

Compared to conventional explosive blasting, the HPGEM has a longer duration of action and a lower intensity. Measurements from the small-scale model experiment indicated that the peak pressure generated by the gas expanders was approximately 581 MPa.

In engineering practice, when rock masses experience dynamic impact loads, their internal energy dissipation mechanisms primarily manifest as interparticle friction and interfacial slip effects along microcracks (including both primary and secondary fractures). In FLAC3D simulations, damping settings are commonly applied to reproduce the energy loss of rock masses under external loading. This study employs the Rayleigh damping model to establish a numerical model for the dynamic response of rock masses, mathematically expressed as:

where C is the damping matrix; M is the mass matrix; K is the stiffness matrix; α is the mass-proportional damping constant; β is the stiffness-proportional damping constant.

For geomaterials, the critical damping ratio typically falls within the range of 2% to 5%, while the minimum central frequency is determined through undamped free-vibration analysis of the model48.

Analysis of numerical simulation vibration

In FLAC3D, vibration velocities at distances of 10 m, 20 m, and 30 m from the blast hole were recorded using the history command. The maximum vibration velocity was observed in the horizontal x-direction, consistent with field monitoring data. Because the numerical model neglected joint fissures present in real rock masses, the attenuation of stress waves within the rock was fine-tuned based on monitoring point data from experiments. This adjustment resulted in PPV values closely matching those in the 10 m region, as shown in Fig. 14.

However, FLAC3D-monitored data in distant regions (10–30 m) underestimate field-measured values by 19.70% ~ 64.24% (as Table 5). This discrepancy likely arises because stress wave attenuation intensifies with distance due to internal defects (e.g., fractures) in the rock mass, whereas the model assumes homogeneous and isotropic rock properties. Consequently, wave attenuation cannot be extrapolated directly from the 10 m zone calibration.

As shown in Table 3, both models exhibit small deviations in PPV values compared to field measurements at closer distances. As the distance increases, the mean error systematically increases with distance. Although the absolute discrepancy remains below 0.1 cm/s, the percentage error becomes more pronounced. Nevertheless, comparison between simulation and field data reveals that both exhibit similar deviation patterns. At the 20 m region, the differences between numerical simulations and field measurements for the four-fracturing-hole and two-fracturing-hole models are both around 20%, while at 30 m, the discrepancy increases to approximately 55% ± 10%. In this study, the far-field PPV results obtained from numerical simulations are mainly used for qualitative analysis of parameter variations. Therefore, correction factors (k₁ = 1.5 and k₂ = 2) were applied to adjust the numerical results, making them more consistent with the field measurements.

Comparison of fracturing hole arrangement

Orthogonal simulation scheme

Subsequent to the initiation of expansion tubes, the high-pressure gas will generate a dynamic shock load surrounding the fracturing hole, thereby inducing vibrations in the surrounding geotechnical mass. Previous studies49 indicate that during vibration wave propagation through geomaterials, attenuation rates are governed by source intensity, propagation medium (geological properties, elevation), distance, and rock-soil characteristics. Notably, energy source intensity exhibits direct correlations with fracture borehole parameters (depth, diameter), charge mass, and borehole horizontal layout configurations. For rock fragmentation in environmentally sensitive zones, optimizing borehole layouts is critical to achieving dynamic control of vibrations and reliable predictability of fracturing outcomes. Consequently, numerical modeling was conducted to simulate fracturing holes with variations in number, depth, X-direction, and Y-direction, enabling systematic comparison of fracturing outcomes. Key simulation parameters for the fracturing holes are detailed in Table 6.

Rock damage analysis

In field experiments, although fracture initiation phenomena are observed on the surface layer of rock mass, the effectiveness of high-pressure gas-induced fracturing still lacks quantitative evaluation criteria. Through joint calibration of dynamic parameters in rock fracturing, rock mass parameters, and site parameters, the quantitative evaluation of fracturing effects can be achieved, specifically the quantitative characterization of rock fracturing extent.

In numerical simulations, when the Y-direction borehole spacing is reduced to the critical threshold, a three-dimensional spatial coupling effect is induced in the plastic zones generated by fracturing from the dual expansion tubes (Fig. 15). This phenomenon carries dual engineering implications: it enhances the fracture density within the fracturing zone while concurrently increasing the energy dissipation rate of elastic waves. Consequently, optimizing borehole layout parameters can achieve optimal connectivity of fracture networks at the rock mass base and maximize rock-breaking energy utilization efficiency. Quantitative analysis of failure modes reveals that tensile failure (blue regions), shear failure (red regions), and their composite failure (green overlapping regions) account for approximately 85.5%, 2.7%, and 12.7% of the total volume, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 15, when the Y-direction borehole spacing increases to 2.00 m, the plastic zone formed by expansion tube fracturing fails to achieve regional interconnection. This phenomenon may result in inadequate crack propagation during the rock-breaking phase, thereby reducing rock mass excavation efficiency. With decreasing Y-direction spacing, an interconnected network gradually forms within the plastic zone of the basal rock mass, markedly enhancing rock-breaking efficacy. Numerical simulations demonstrate that a Y-direction spacing of 1.50 m not only ensures effective rock fracturing but also optimizes the energy utilization rate of the expansion tube. Similar critical failure characteristics were observed in the parameter system of X-direction borehole spacing.

Furthermore, in the study investigating the influence of borehole burial depth on fracture morphology, quantitative analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between burial depth and plastic zone distribution. This mechanical response directly manifests as follows: when the burial depth exceeds the critical threshold (1.5–2.0 m), fractures fail to propagate to the surface geological interface (distance > 0.9 m), resulting in a higher integrity index of the overlying rock strata. In numerical models, the propagation of plastic zone under varying burial depths is visually demonstrated (Fig. 16).

Experimental data in Fig. 16 demonstrate that at a borehole burial depth of 1.5 m, the surface damage zone and rock mass failure belt form a continuous penetration pattern, confirming optimal rock-breaking effectiveness at this depth and achieving targeted stratified fracturing. When the burial depth increases to 2.0 m, localized plastic zone appear on the surface (with a 78.3% reduction in coverage area), attributable to two mechanisms: (1) Increased burial depth leads to enhanced blast energy attenuation, resulting in insufficient energy reaching the free surface for effective rock fragmentation. (2) The constitutive model employs Mohr–Coulomb continuum theory, which exhibits inherent limitations in simulating cross-scale evolution of microcracks through numerical methods, necessitating mesoscale validation via coupled DEM-FDM algorithms.

At burial depths exceeding the 2.0 m threshold, the apex of the damage zone shifts more than 0.9 m from the free surface, rendering the blast energy inadequate to meet engineering requirements for practical rock-breaking applications.

Quantitative calculation of the plastic zone volume in the model (Fig. 17) indicates that the rock fragmentation efficiency achieves its global optimum when employing the parameter combination of borehole burial depth (1.5–2 m), Y-direction = 1.5 m, and X-direction = 3.5 m. Numerical simulation verification results based on this parameter system are shown in Fig. 18.

As shown by the characteristics of the yellow zone in the figure, when the borehole burial depth is 1.5 m, the rock fragmentation dynamic parameters exhibit superior characteristics. The plastic zone network forms a well-connected structure with the free surface, achieving an effective fractured zone volume of 21.4 m3, representing an increase by a factor of 2.2 to 2.8 compared to previous working conditions. The maximum plastic zone depth extends to 2.5 m, with a surface plastic zone projection area of 12 m2. Under this parameter set, rock-breaking energy utilization is fully optimized, and the fragmentation effect meets the technical specifications for engineering excavation requirements.

PPV analysis

Under the condition of increasing the number of rows in fracturing hole arrays, the vibration waves generated by multi-hole synchronous fracturing exhibit multi-source interference and superposition characteristics. Numerical simulations reveal that the vibration wave superposition from multi-row fracturing holes demonstrates dual spatiotemporal phases: vibration waves excited by adjacent holes within the same row first achieve in-phase superposition, followed by the formation of secondary interference effects with vibration waves from adjacent rows. Vibration data analysis (as shown in Fig. 19a) indicates that when the number of fracturing hole rows increases from one to three, the PPV at 10 m from the blast source surges by 143.6%, whereas the PPV increment at 30 m measures only 38.4%. This response characteristic demonstrates that the vibration intensity amplification is closely related to the blast center distance, confirming the physical mechanism whereby near-field vibration effects are predominantly governed by inter-hole coupling interactions.

Under equivalent expansion agent conditions, the burial depth of expansion tubes exerts a dominant control effect on near-field (10 m) vibration intensity (Fig. 19b). Data demonstrate that when the burial depth decreases from 3.0 m to 1.5 m, the PPV in near-blast regions (10 m) increases by 15.6%. In the 20 m and 30 m zones (Fig. 19c, d), different hole burial depth induces PPV to fluctuate within small intervals, with overall vibration levels stabilizing near 0.43 cm/s and 0.19 cm/s, respectively.

In the model, adjusting the Y-direction of expansion tubes shows limited impact on PPV, displaying an overall trend of initial decrease followed by increase. The minimum PPV occurs at Y-direction = 1.5 m, attributed to enhanced stress wave superposition between adjacent expansion tubes that elevates localized energy density. Similar to Y-direction, increasing X-direction reduces energy density, leading to PPV attenuation. Notably, as X-direction increases, the outermost fracturing holes become closer to the measurement points, causing the proximity effect of these peripheral holes to outweigh the energy superposition effects from fracturing holes. As measurement distance increases, horizontal borehole spacing demonstrates a negative correlation with PPV. This indicates that enlarging the horizontal spacing of fracturing holes can effectively mitigate their environmental impacts in far-field regions.

Furthermore, vibration and rock-breaking effects show a degree of correlation. As shown in Fig. 17, under standard conditions (as listed in Table 4), when the distance-x increases from 2.0 m to 3.5 m, the change in the plastic zone area is only 0.3%, while the rock-breaking vibration in the middle and far-field regions (20 m and 30 m) decreases by 10.2% and 15.9%, respectively. Therefore, without considering differences in fragment size, moderately increasing the horizontal spacing of boreholes within a reasonable range can effectively reduce mid- and far-field vibrations.

Field verification

To validate the practical feasibility of the aforementioned research, a series of field verification tests were conducted under the target hard rock geological conditions. During the testing process, blowout phenomena were observed. Consequently, the borehole sealing material was replaced with a mixture of anchoring agent and rapid-hardening dry cement, and hard rock fragments were covered with heavy-duty fabric above the fracturing holes to prevent rock spalling. This paper presents and analyzes successful dual-hole and quad-hole tests (Fig. 20). The borehole layout parameters were uniformly set as follows: hole depth of 2 m, inclination angle of 60° to the ground surface, y-direction spacing of 1 m, and x-direction spacing of 3 m.

As shown in Fig. 20, after the expansion tubes were triggered, although no large rock mass ejection occurred, dense cracks formed around the fracturing holes. Upon completion of rock fragmentation, the rock mass was processed using a hydraulic breaker. This revealed well-developed internal fractures, significantly improving fragmentation efficiency and effectively reducing mechanical wear. The maximum peak particle velocity (PPV) recorded by a vibrometer at 20 m from the blast source was 0.71 cm s⁻1. In the quad-hole experiment, increasing the number of expansion tubes enhanced the rock fragmentation energy and significantly amplified the multi-hole synergistic effect. Figure 20(b) clearly shows large rock masses being displaced by the “gas wedge” effect, with distinct fissures forming around them. The maximum PPV recorded at 30 m from the blast source was 0.37 cm s⁻1.

Discussion

This study systematically investigates the effectiveness and mechanisms of HPGEM in shaft foundation excavation through small-scale model experiments and preliminary field tests. It also provides critical engineering validation for the application of non-explosive rock-breaking technology via full-scale field trials. This section will delve into the implications of the findings, current research limitations, and future research directions.

Research significance

This study has achieved important breakthroughs in both the scientific understanding and engineering application of the HPGEM. Through carefully designed small-scale model experiment, the direct quantitative observation of borehole wall stress under the action of the expansion tube was achieved for the first time, with a measured peak stress of up to 581 MPa under specific triggering conditions. This key data breaks through the previous limitation of relying solely on theoretical estimations to evaluate the expansion tube’s action strength, providing direct experimental evidence for understanding the dynamic process of brittle fracture induced by HPGEM in hard rock, and deepening the understanding of its mechanical nature.

The study reveals that under the rapid loading of high-pressure gas, the rock fracture is dominated by tensile mechanisms, providing experimental support and a theoretical foundation for analyzing the non-explosive and low-disturbance rock-breaking mechanism. Meanwhile, this study establishes an “experiment–numerical coupling” analytical framework integrating PVDF piezoelectric sensor testing and FLAC3D numerical inversion, which enables the dynamic stress data obtained from model tests to be effectively calibrated and extrapolated to field conditions, realizing a verifiable transformation between experimental and engineering scales.

In addition, the study systematically reveals the coupling influence laws of key parameters such as expansion hole depth, hole spacing, and expansion tube arrangement density on near-field vibration characteristics and fracture efficiency, and determines the optimal parameter combination under specific conditions, providing a feasible methodological reference for exploring optimal parameter combinations under different conditions.

In summary, the significance of this study goes beyond the empirical verification of HPGEM feasibility, elevating it from the “engineering experience stage” to a low-disturbance hard rock fracturing system supported by quantifiable design bases and mechanical mechanism understanding, thus providing both theoretical and practical support for safe and efficient rock excavation in environmentally sensitive areas.

Research limitations

Although this study predicted the borehole layout scheme and vibration response of HPGEM, several limiting factors remain inadequately addressed20,32,43. Firstly, while the scale of the small-scale model experiment aligns well with actual field experiments, the size effect of rock cannot be overlooked. Secondly, although different ratios of gas-generating agents and oxidizers were tested in the preliminary experiments, the differences in performance were not significant, and therefore this aspect was not further investigated. However, it is theoretically evident that different mixing ratios and tube dimensions of the expansion agent would lead to variations in rock-breaking performance. Hence, in future research, it is necessary to conduct further analyses on the energy efficiency of expansion tubes with different gas-generating and oxidizing agent compositions. Finally, although field validation experiments confirmed the feasibility of the optimal rock-breaking borehole parameters derived from comparative studies, the balance between rock-breaking vibration and fragmentation effectiveness has not been deeply investigated.

Additionally, while FLAC3D software can simulate rock-breaking processes of HPGEM with relatively low computational costs, its non-discrete mesh and reliance on specific assumptions and simplifications—such as treating the formation as a homogeneous isotropic medium while neglecting potential changes during rock fragmentation or geological weak zones—prevent it from effectively simulating micro-crack propagation processes. Therefore, although the model can to some extent analyze the rock-breaking effects, it still holds further research value in terms of simulating and evaluating rock fragment size distribution.

Future research directions

Future research on the energy efficiency of expansion tubes should further investigate the effects of different size combinations and expansion agent ratios on the borehole wall. Concurrently, discrete element models (such as PFC) should be employed to more accurately replicate the gas expansion process by simulating particle expansion or localized particle increase. This approach will not only enable a more precise reconstruction of the “gas wedge” mechanism but also facilitate an in-depth exploration of crack initiation and macroscopic crack propagation laws. These insights will lay a solid foundation for the practical application of HPGEM technology in the field of directional fracturing.

Furthermore, existing research has repeatedly highlighted the advantages of HPGEM, namely its low-disturbance characteristics and operational convenience. Therefore, to promote the wider application of this technology in environmentally sensitive areas, it is crucial to conduct multidimensional rock-breaking designs that integrate borehole layout parameter optimization with rock-breaking energy control. Only by ensuring effective rock fragmentation while simultaneously controlling vibration impacts can the advantages of this method be fully realized, establishing it as a reliable technique for efficient rock breaking in environmentally sensitive zones.

In conclusion, this study confirms the feasibility of applying HPGEM for rock breaking in projects with stringent vibration control requirements, provided that borehole layout parameters are optimized to balance vibration impact with fragmentation effectiveness. These findings provide valuable references and practical guidance for addressing the challenge of achieving efficient, low-disturbance rock breaking in hard rock environments. Future research should build upon these results, focusing on enhancing the application efficacy of HPGEM and similar technologies (such as carbon dioxide phase-transition fracturing) in environmentally sensitive areas.

Conclusion

This study integrates small-scale model experiment, field experiments, and numerical simulations to investigate the rock fragmentation effects and vibration impacts of the HPGEM. Research initially established equivalent mechanical model tests, utilizing a PVDF sensor array to precisely invert the time-varying pressure field on borehole walls and reconstruct the load curve of the expansion tube acting on borehole surfaces. Following precise calibration of the numerical model using this data, an analysis was conducted on rock fragmentation efficiency and vibration characteristics under different borehole layout schemes. Finally, field experiments verified the accuracy of the above research, leading to the following conclusions:

-

1.

Dynamic monitoring using PVDF piezoelectric sensors installed in the small-scale model revealed that the peak stress at the borehole wall interface during the rock-breaking process reached 581 MPa, exceeding the strength threshold of the limestone formation, thereby confirming the effectiveness of the fracturing mechanism in limestone strata. It should be noted that while existing PVDF sensing systems can capture pressure evolution during the pre-peak phase, the pressure unloading curve remains unattainable as the electric charges deposited on both sides of the piezoelectric film do not discharge through the measuring circuit.

-

2.

The FLAC3D-based multivariable borehole layout model indicates that the fracture efficiency of the limestone formation gradually increases as the burial depth decreases, reaching optimal performance at a burial depth of 1.3 m (borehole depth of 1.5 m), which represents an 18.7% improvement compared with a burial depth of 1.7 m (borehole depth of 2 m). When the hole-bottom spacing to row spacing (Y-direction and X-direction) ratio is optimized to 1.5 m × 2.0 m, the continuity between plastic zone and free faces reaches optimal levels, providing favorable free surfaces for subsequent fracturing.

-

3.

Simulation and field test results jointly indicate that when the burial depth is less than 2.0 m, shallower fracturing boreholes produce more pronounced near-field vibrations. Moreover, reducing the horizontal spacing between boreholes causes an energy concentration effect, which further amplifies the vibration intensity.

-

4.

The numerically optimized borehole layout scheme demonstrates outstanding rock fragmentation performance in field applications, significantly enhancing hard rock excavation speed while maintaining a low disturbance level. Although no rock ejection occurred in the dual-borehole experiments, the extensive network of fractures created favorable conditions for subsequent rock breaking, substantially reducing wear on mechanical rock-breaking equipment. When applied to other hard rock formations, the parameter combination should be re-determined based on their mechanical properties, following the optimization procedure presented here, to ensure engineering applicability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, X. et al. Research on the impact of underground excavation metro on surface traffic safety and assessment method. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 46(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533839.2023.2170928 (2023).

Wang, S. & Zhu, S. Vibration impact of rock excavation on nearby sensitive buildings: An assessment framework. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 163, 107508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2022.107508 (2022).

Liu, D., Zhang, X., Tang, Y., Jin, Y. & Cao, K. Study on the Impact of different pile foundation construction methods on neighboring oil and gas pipelines under very small clearances. Appl. Sci. 14(9), 3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14093609 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Structural vibration identification in ancient buildings based on multi-feature and multi-sensor. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 25(09), 2550094. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455425500944 (2025).

Li, S., Sun, X., Shi, C., Kang, R. & Yang, F. Dynamic response and regular analysis of adjacent buildings under blasting construction across foundation pits of subway stations. Structures. 66, 106903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106903 (2024).

Duan, L., Lin, W., Lai, J., Zhang, P. & Luo, Y. Vibration characteristic of high-voltage tower influenced by adjacent tunnel blasting construction. Shock Vib. 2019(1), 8520564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8520564 (2019).

Jahed Armaghani, D. et al. Neuro-fuzzy technique to predict air-overpressure induced by blasting. Arab. J. Geosci. 8(12), 10937–10950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-015-1984-3 (2015).

Zhang, Z. Kinetic energy and its applications in mining engineering. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.01.009 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Review on vibration monitoring and its application during shield tunnel construction period. Buildings 14(4), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14041066 (2024).

Cao, L., Zhang, D., Fang, Q. & Yu, L. Movements of ground and existing structures induced by slurry pressure-balance tunnel boring machine (SPB TBM) tunnelling in clay. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 97, 103278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.103278 (2020).

Bilgin, N., Dincer, T., Copur, H. & Erdogan, M. Some geological and geotechnical factors affecting the performance of a roadheader in an inclined tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 19(6), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2004.04.004 (2004).

Cao, Y. et al. CO2 gas fracturing: A novel reservoir stimulation technology in low permeability gassy coal seams. Fuel 203, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.04.053 (2017).

Wang, B., Li, H., Shao, Z., Chen, S. & Li, X. Investigating the mechanism of rock fracturing induced by high-pressure gas blasting with a hybrid continuum-discontinuum method. Comput. Geotech. 140, 104445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104445 (2021).

Sheng-tao, Z., Xue-dong, L. U. O., Nan, J., Zong-xian, Z. & Ying-kang, Y. A review on fracturing technique with carbon dioxide phase transition. Chin. J. Eng. 43(7), 883–893. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn2095-9389.2020.11.05.006 (2021).

Habib, K. M., Vennes, I. & Mitri, H. Laboratory investigation into the use of soundless chemical demolitions agents for the breakage of hard rock. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00547-4 (2022).

Natanzi, A. S., Laefer, D. F. & Connolly, L. Cold and moderate ambient temperatures effects on expansive pressure development in soundless chemical demolition agents. Constr. Build Mater. 110, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.016 (2016).

Cho, H., Nam, Y., Kim, K., Lee, J. & Sohn, D. Numerical simulations of crack path control using soundless chemical demolition agents and estimation of required pressure for plain concrete demolition. Mater. Struct. 51(6), 169. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-018-1292-y (2018).

Cho, S. H., Cheong, S. S., Yokota, M. & Kaneko, K. The dynamic fracture process in rocks under high-voltage pulse fragmentation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(10), 3841–3853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1031-z (2016).

Cho, S. H. et al. Electrical disintegration and micro-focus X-ray CT observations of cement paste samples with dispersed mineral particles. Miner Eng. 57, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2013.12.019 (2014).

Liu, D. et al. Cutting tests of high pressure gas expansion rock-breaking technology in urban small cross-section hard-rock tunnel. Blasting 36(03), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.3963/j.issn.1001-487X.2019.03.016 (2019).

Liu, D. W. et al. On the safety evaluation of the high pressure gas expansion method for the subway connecting passage excavation. J. Saf. Environ. 19(05), 1511–1517. https://doi.org/10.13637/j.issn.1009-6094.2019.05.004 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Investigation on the key techniques and application of the new-generation automatically formed roadway without coal pillars by roof cutting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 152, 105058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2022.105058 (2022).

Zhu, W. C., Gai, D., Wei, C. H. & Li, S. G. High-pressure air blasting experiments on concrete and implications for enhanced coal gas drainage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 36, 1253–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.03.047 (2016).

Xiao, C., Ni, H. & Shi, X. Unsteady model for wellbore pressure transmission of carbon dioxide fracturing considering limited-flow outlet. Energy 239, 122289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.122289 (2022).

Esen, S., Onederra, I. & Bilgin, H. A. Modelling the size of the crushed zone around a blasthole. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 40(4), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(03)00018-2 (2003).

Zhu, W. C., Wei, C. H., Li, S., Wei, J. & Zhang, M. S. Numerical modeling on destress blasting in coal seam for enhancing gas drainage. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 59, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.11.004 (2013).

Zhang, Y., Deng, H., Ke, B. & Gao, F. Research on the explosion effects and fracturing mechanism of liquid carbon dioxide blasting. Min. Metall. Explor. 39(2), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-021-00514-8 (2022).

Li, Q. Y., Chen, G., Luo, D. Y., Ma, H. P. & Liu, Y. An experimental study of a novel liquid carbon dioxide rock-breaking technology. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 128, 104244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104244 (2020).

Hu, J. et al. Experimental study of breakup and atomization characteristics of liquid carbon dioxide jet under high-pressure environment. Acta Astronaut. 216, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2023.12.057 (2024).

Yu, C. et al. Analysis of impact pressure, rock-breaking effect, and ground vibration induced by the disposable CO2 fracturing tube. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16(8), 3099–3121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.04.012 (2024).

Zhang, Q. et al. Instantaneous expansion with a single fracture: A new directional rock-breaking technology for roof cutting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 132, 104399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104399 (2020).

Liu, D., Wang, C., Tang, Y. & Chen, H. Application of high-pressure gas expansion rock-cracking technology in hard rock tunnel near historic sites. Appl. Sci. 13(2), 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13021017 (2023).

Zhou, S., Jiang, N., He, X. & Luo, X. Rock breaking and dynamic response characteristics of carbon dioxide phase transition fracturing considering the gathering energy effect. Energies 13(6), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061336 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Deng, J., Deng, H. & Ke, B. Peridynamics simulation of rock fracturing under liquid carbon dioxide blasting. Int. J. Damage Mech. 28(7), 1038–1052. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056789518807532 (2019).

Wang, X., Wang, E., Liu, X. & Zhou, X. Failure mechanism of fractured rock and associated acoustic behaviors under different loading rates. Eng. Fract. Mech. 247, 107674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2021.107674 (2021).

Huo, X. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on the peak value and loading rate of borehole wall pressure in decoupled charge blasting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105535 (2023).

Jayasinghe, L. B., Shang, J., Zhao, Z. & Goh, A. T. C. Numerical investigation into the blasting-induced damage characteristics of rocks considering the role of in-situ stresses and discontinuity persistence. Comput. Geotech. 116, 103207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.103207 (2019).

Talhi, K. & Bensaker, B. Design of a model blasting system to measure peak p-wave stress. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 23(6), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0267-7261(03)00018-6 (2003).

Wei, X. et al. Experimental investigations of direct measurement of borehole wall pressure under decoupling charge. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 120, 104280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104280 (2022).

Tan, S. Polarization and dynamic shock calibration of poly (vinylidene fluoride) film. Univ. Sci. Technol. China https://doi.org/10.27517/d.cnki.gzkju.2020.000208 (2020).

Huang, X. Research on the method and technology of direct testing the wall pressure of contour blasting holes. Cent. South Univ. https://doi.org/10.27661/d.cnki.gzhnu.2023.000262 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Optimizing flyrock forecasting in open-pit blasting using hybrid machine learning models. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04730-2 (2025).

Baoxin, J. et al. Attenuation model of tunnel blast vibration velocity based on the influence of free surface. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 21077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00640-9 (2021).

Bauer F. Advances in piezoelectric PVDF shock compression sensors. In 10th International Symposium on Electrets. 647–650 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISE.1999.832129.

Peng, H. et al. The vibration response to the high-pressure gas expansion method: A case study of a hard rock tunnel in China. Appl. Sci. 14(15), 6645. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156645 (2024).

Ye, Z. et al. Attenuation characteristics of shock waves in drilling and blasting based on viscoelastic wave theory. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 171, 105573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105573 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Study on the stress field and crack propagation of coal mass induced by high-pressure air blasting. Minerals. 12(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12030300 (2022).

Qiu, H. et al. Study on the damage pattern of the cemented backfill at the jagged rock-fill interface under dynamic loading of blasting. J. China Coal Soc. 50(04), 2037–2050. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1635 (2025).

Monjezi, M., Ahmadi, M., Sheikhan, M., Bahrami, A. & Salimi, A. R. Predicting blast-induced ground vibration using various types of neural networks. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 30(11), 1233–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2010.05.005 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The test site for this study was provided by CCCC Road and Bridge South Engineering Co., Ltd. and Zhongtian Blasting and Geotechnical Engineering Co., Ltd. (Zixing Branch).

Funding

This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council (Grant No.202406370107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu Dunwen: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Yuhui Jin: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Software, Data curation. Kunpeng Cao: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Yu Tang: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Chong Wang: Methodology, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Jin, Y., Cao, K. et al. Study on rock fragmentation and vibration response characteristics in hard rock formations using high-pressure gas expansion method. Sci Rep 15, 42995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27044-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27044-3