Abstract

Silicified wood serves as a crucial geological archive, recording significant information about palaeoenvironment, palaeoecology, palaeontology and diagenetic conditions. However, temperature and pressure conditions of silicification remain poorly constrained. In this study, we analysed primary fluid and carbonaceous material inclusions in quartz from silicified wood in the Qitai Silicified Forest, Xinjiang. Microthermometry and Raman spectroscopic studies reveal the methane-bearing silicification fluids, with salinities of 12.05–14.87 wt% NaCl equiv., densities ranging from 0.94 to 0.96 g/cm3, homogenization temperatures in the range of 238–257 °C, and provide the converting temperatures of 285 ± 30 °C for carbonaceous inclusions. Silicification temperatures are constrained to 238–315 °C, supported by successive silica precipitation. The thermal model analysis of inclusion isochores and thermobaric gradients, burial history of the Junggar Basin, and the presence of volcanic tuff hosting silicified wood limit the silicification pressure in the range between 0.1 MPa (surface conditions) and ~ 50 MPa. These findings provide the first quantitative P–T constraints on wood fossilization, revisit its thermal limits, and facilitate the study of wood fossil genesis in volcanic environments globally. Quantifying the P–T thresholds of wood silicification not only renews models of plant fossil preservation but also provides insights into how forest fossils reflect extreme palaeoenvironments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modification of wooden material in geological processes is represented by five most typical products: (1) organic matter and other organic degradation compounds; (2) mummified wood retaining its original structure1; (3) fossil fuel, e.g. coal and petroleum, and even high-grade metamorphic products, such as anthracite and graphite2; (4) amber, the fossil product of tree resin3; and (5) petrified wood, where cells filled with organic matter are partially replaced by inorganic matter, such as quartz, calcite, apatite, uranium minerals etc4,5. Silicification is a particularly effective preservation process, maintaining detailed cellular structures as well as enhancing wood strength, weathering and biodegradation resistance6. Silicified wood occurs across diverse geological settings, including volcaniclastics, sediments, and hot springs, though volcanic environments appear to be notably significant7,8,9,10. Compared to surface hot spring environment, volcanic settings may offer higher variability in the conditions of silicification processes, with early silicification potentially happening in the vapor stability field of H₂O11.

Wood silicification imprints critical palaeoenvironmental information during fossilization, yet direct data on its temperature and pressure conditions are scarce, leaving our understanding speculative2,12,13. The physicochemical conditions of wood silicification can be reconstructed through two complementary approaches: microthermometry of fluid inclusions and Raman thermometer of carbonaceous materials14,15,16,17. Although fluid inclusions provide direct constraints on palaeo-mineralizing fluids, their documented occurrences in silicified wood remain exceptionally rare, with only a single authenticated case reported from Chemnitz, Germany11. In the study of Raman thermometry of carbonaceous materials, the term “carbonaceous material” typically refers to amorphous or partially ordered carbon-bearing materials undergoing an irreversible progressive transformation toward pure carbon end-member crystalline graphite, a process known as graphitization16,18. The structural evolution of carbonaceous materials during thermal maturation exhibits systematic, temperature-dependent changes measurable by Raman spectroscopy18,19. While this organic geothermometer has been extensively calibrated in metamorphic systems, its application to silicified wood has remained conspicuously absent, creating a critical gap between empirical observations and theoretical models of plant fossil preservation16,17,20,21.

While silicification of wood is generally considered to take place at relatively low temperatures, the high maturity of carbonaceous material in Chemnitz silicified wood indicates potential for elevated temperature silicification under hydrothermal settings2. Experimental simulations of wood silicification have succeeded at temperatures between 15 and 150 °C7,8,11,22,23. Additionally, natural silicification at higher temperatures may possibly take place, given that thermal modifications of wood were also observed at 150–240 °C under controlled atmospheres (air, vacuum, inert gases, or water and saturated steam)24.

This study addresses the first quantitative P–T conditions and chemical compositions obtained by fluid inclusion and carbonaceous-material thermometry in a mega-quartz of silicified wood in Qitai Silicified Forest (QSF), Xinjiang, the most prominent fossil forest in Asia25, redefines the preservation mode of woody plants in volcanic environments, and elucidates its palaeoecological significance.

Methods

Fluid inclusion microthermometry

The experiments were conducted at the Resources Exploration Laboratory of China University of Geosciences, Beijing, through a LINKAM MDSG 600 heating-cooling stage equipped with a Zeiss microscope. Liquid nitrogen and a thermal resistor were used while freezing and heating, respectively, within the temperature range of – 196 to 600 °C. Fluid inclusions were initially cooled to approximately − 190 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and was maintained for 5 min to ensure complete freezing. The heating rate was typically set at 5–10 °C/min during the initial stages of each heating run, with a reduction to 0.5–1 °C/min near phase transition points. Eventually, ice-melting temperatures (Tm) and homogenization temperatures (Th) of fluid phases in fluid inclusions were obtained.

Calculation of physicochemical properties of fluid inclusions

Salinities of liquid-vapour two-phase inclusions were obtained using the final melting temperatures of ice26 and reported as wt% NaCl equiv. Densities and amount-of-substance fractions of all components were calculated using the BULK program in FLUIDS package27, whereas homogenization pressures and isochores of individual fluid inclusions were calculated with the ISOC program.

Raman thermometry of carbonaceous materials

Laser micro-Raman spectroscopic analyses were performed with a HR-Evolution Micro Raman spectrometer at the Gemmology Experimental Teaching Centre, China University of Geosciences (Beijing). A frequency-doubled Nd: YAG laser (λ = 532 nm) and a grating of 600 gr/mm was used for analysis of the fluid and carbonaceous material inclusions of quartz. Each spot was analyzed for 30 s (five acquisitions, 6 s each) in the range of 900–4000 cm− 1. The dramatic impact of mechanical polishing on the Raman spectra of carbonaceous materials could be avoided by testing carbonaceous material inclusions embedded in transparent minerals28. Background noise was corrected by subtracting a linear baseline in the spectral range of 1000–1750 cm− 1. Characteristic bands of carbonaceous materials were fitted with pseudo-Voigt function (Gaussian-Lorentzian Sum)17 and the centre position, intensity (height) and full width at half maximum (FWHM) were determined.

Results

Field observation

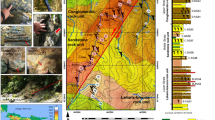

The QSF is situated approximately 100 km northeast to the downtown of Qitai County, Xinjiang, China, ~ 30 km to the town of Jiangjunmiao. It emerges at the eastern Shishugou Formation outcrops along the southern margin of the Kalamaili Range in the eastern Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China (Fig. S1)29,30. Silicified wood stumps mainly support the tops of heavily weathered slopes, with purplish red tuff visible at the root. Notably, no apparent traces of secondary silicification (i.e., silicified cementation or quartz vein) were found in the surrounding settings of silicified wood. Some silicified logs lie on the weathered surface along with numerous small fragments (Fig. 1a,b).

In some polished silicified trunks, white euhedral quartz grew in clusters along the inner wall of the centre cavity, while other cavities are filled with large grains of white calcite (Fig. 1c,d). A colourless and transparent mega-quartz crystal taken from the druse was used for fluid inclusion and carbonaceous-material thermometry analysis, which was then polished into a small, doubly parallel, 3.0 mm-thick piece. Other samples for microscopic observation were taken from the trunks or stumps in the field.

Petrography

In this transverse section, the cellular structure of wood precursor was partially replaced and permineralized by silica, which is referred to as the silicified wood substrate. It appears brownish and is surrounded by radial colourless euhedral quartz crystals. This pattern has been reported in other localities and is referred to as ‘pointstone preservation’31,32,33. The remaining spaces were filled by colourless calcite crystals (Fig. 2a‒d). Inside the pattern, irregularly shaped and brown to black materials portray as either the cell wall of the cellular framework in the centre, or inclusions in the outer rim quartz, generally appearing in a constant diffuse trend (Fig. 2c,d). Some large, euhedral quartz crystals grew from the inner substrate, extending beyond the cellular boundaries, with only euhedral terminations exposed outside the cell structure. It appears to be a “popcorn” texture where wood tissue has been “exploded” from expansive crystal growth (Fig. 2e,f). This phenomenon may be explained by the wood tissue having been partially mineralized, causing the disrupted cells to have well-preserved morphology. These findings suggest a continuous process of silica precipitation from the substrate lumina to epitaxial quartz, despite the influence of cell structure. Contrastingly, the large number of intricately distributed impurities between calcite and the outer surfaces of quartz are indications of significant crystalline discontinuities, suggesting a post-silicification origin of calcite. Moreover, no signs of recrystallisation, such as unusual extinction and inclusion distribution, are found in the silica phase34,35.

Micrographs of a transverse section of Qitai silicified wood. Bright interference colors are due to a larger thickness of the section than the conventional 30 μm. (a and b) The silicified wood substrate (brown), quartz and calcite crystals (colorless) coexist in the sample. Transmitted and polarized light. (c and d) Quartz-enclosed wood substrate. Transmitted and polarized light. (e and f) Transition region of the inner silicified wood substrate, large quartz grains with euhedral terminations and outer calcite. Polarized light. SW = silicified wood, Cal = calcite, Qtz = quartz, CS = cellular structure.

Microthermometry and chemical compositions of fluid inclusions

Microthermometry analyses were carried out on primary inclusions, without inelastic tensile deformation or leakage signs (Fig. 3). Only one type of liquid-rich two-phase primary inclusions was identified, with similar gas-phase ratio accounting for ~ 5‒13% of the inclusion volume at room temperature. All of them homogenized to a liquid phase during microthermometric measurements. The final ice-melting temperatures of the fluid inclusions vary from − 10.9 to − 8.3 °C, indicating salinities of 12.05–14.87 wt% NaCl equiv. The densities were estimated based on the salinities and the volume fraction of gaseous phases, ranging from 0.94 to 0.96 g/cm3. Total homogenization temperatures mainly varied from 238 to 257 °C (n = 15), with a single outlier at 281 °C potentially indicating post-entrapment thermal reequilibration (Table 1)36,37. The results of Raman analyses reveal that the vapor phases of fluid inclusions mainly consist of methane (CH4) and H2O mixture in varying proportions, with trace amounts of CO2 (Fig. 3a, S2‒4). The liquid phases are almost entirely H2O (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that the siliceous fluid at QSF is characterized by a ternary fluid system of CH4–H2O–NaCl.

Raman thermometry of carbonaceous materials

The dark solid flakes in quartz are randomly dispersed as isolated individuals or clusters, with irregular shape or occasional hexagonal shape with uneven edges (Fig. S5). They show the characteristic bimodal spectra of carbonaceous materials (Fig. 3c). Raman spectra of the sample (Fig. 3d) are dominated by a G and/or D2 band (designated as D2 (GL) in Text S2) and a prominent D1 band, with a faint D4 shoulder and a very wide D3 band, suggesting a relatively high degree of structural disorder. The calibration of Raman carbonaceous material geothermometer proposed by Kouketsu et al. (2014)17 was used, as it is suitable for low temperature (150–400 °C) metamorphic carbonaceous materials. Calculations yielded temperatures of 285 ± 30 °C for the samples (Text S2, Table 2)37, indicating that the structure of carbonaceous material inclusions was in the transition stage of low- to medium-grade metamorphism and started to transform from amorphous carbon to crystalline graphite.

a D2 band is equivalent to GL peak in this case.

Discussion

Carbonaceous materials can be formed either by converting organic matter into graphite at increasing temperatures, or by precipitating from carbon–oxygen–hydrogen (C–O–H) fluids19,38. The carbonaceous materials of epigenetic origin typically occurs in vein- or pod- type deposits39. In terms of crystal morphology, fluid-deposited carbonaceous materials may exhibit high crystallinity and homogeneity under high-temperature conditions. Alternatively, it may adhere to pre-existing crystalline graphite as amorphous carbon or precipitate in fluid inclusions as daughter crystals or as amorphous coatings of the inclusion walls39,40,41,42,43,44. Petrographic observations in Qitai silicified wood did not reveal such morphology of fluid-deposited carbonaceous materials, or any textural intergrowth of carbonaceous materials with hydrous phases (Fig. S5), suggesting that graphite nucleation from fluid was hindered under relatively low-temperature and low-pressure conditions45.

In addition to fluid precipitation, amorphous carbon can also arise from the graphitization of organic matter18,43. In the specific case of silicified wood, the wood precursors could provide a substantial source of organic matter. In-situ metamorphism of organic matter commonly yields carbonaceous materials in the form of dispersed graphite flakes39, which is consistent with the petrographic observations in this study. Charcoal-like appearance of wood fossils has been observed at the QSF (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, based on our results of fluid inclusion microthermometry, the fluid at ~ 250 °C has the ability to induce transformation in carbonaceous materials17. Therefore, it is more likely that the low-crystallinity carbonaceous material inclusions in Qitai silicified wood originated from the thermal conversion of organic matter during heating. The pathway of graphitization is not accessible to all carbonaceous organic precursors. Hydrogen-rich precursors yield graphitizable carbon after carbonization, whereas oxygen-rich ones form non-graphitizable carbon18,46. The brown residue preserved inside the fossil wood structure (Fig. 2c‒f) likely represents a pyrolytic product of early carbonization that preceded the onset of graphitization.

As the temperature increases, the graphitization process is highly associated with the enhancement of crystal structure order. Owing to the irreversibility of graphitization, the products are believed to record approximate peak temperature of metamorphism16\. Thus, the Raman thermometer result of 285 ± 30 °C could be considered as the upper limit of the temperature of silicification process. Nevertheless, numerous factors can contribute to variations in the crystallinity of carbonaceous materials, such as precursor type, deformation, precipitation from fluid, or dissolution and reprecipitation of carbonaceous materials42. Significant deformation and reprecipitation can be excluded in this case based on the undeformed and continuously crystalline structure of wood cells and quartz (Fig. 2)47. Thus, the most relevant factors controlling graphitization are the duration of thermal event and the kinetics of reactions between wood and fluid48,49. The correspondence between temperature and crystallinity is obtained under the premise that the system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium at a specific temperature. Before reaching thermodynamic equilibrium, the degree of graphitization is time-dependent and progresses with elapsed time48,50. That means, since we cannot determine the duration of hydrothermal interaction and whether the graphitization process had reached equilibrium, the actual peak temperature of this hydrothermal fluid might be higher than 285 ± 30 °C.

The stable vapour-liquid ratio in the fluid inclusions of quartz indicates that the fluid was captured from a homogeneous fluid system. Since the absence of phase separation, the homogenization temperatures can only represent the minimum temperature of fluid entrapment. To estimate the actual entrapment temperature-pressure conditions, a thermal model based on the local geothermal gradient can be used14. The isochores (P–T relation) were calculated and then plotted together with the lithostatic and hydrostatic thermobaric gradients51,52,53. The intersection zone (yellow region in Fig. 4a) ought to represent the theoretical P–T conditions of entrapment, yielding 299–528 °C and 117‒469 MPa. According to the local geothermal gradient (24 °C/km)51, the entrapment depth at these P–T conditions is within the range of 11.7 to 21.3 km.

Thermal models for P–T constrains. (a) The intersection of the fluid inclusion isochores in QSF quartz and the geothermal gradients (yellow area) represents the theoretical entrapment temperature and pressure of fluids under local thermobaric gradient. The realistic P–T range (green area), constrained by the maximum pressure (~ 90 MPa) derived from the burial history at the Junggar Basin margin and the highest temperature obtained from carbonaceous materials, lies outside of the yellow region. (b) The red and blue areas represent the restricted P–T conditions of the early or final stages of silicification, respectively. The blue area is constrained by isochores, the liquid-vapor curve of pure water and the bubble point curve of the CH4–H2O–NaCl fluid mixtures at x bulk (CH4) = 0.001, m NaCl = 3 mol/kg. The bubble point curve was modified after Mao et al. (2013)54.

However, in the burial history of the Junggar Basin, the Middle‒Late Jurassic strata have never reached such depths, with a maximum depth of 6 km in the hinterland and only shallow depths at the margins52,53. As the QSF is located in the Middle‒late Jurassic sedimentary strata, the overlying rocks were the main source of pressure in the homogeneous system of the late-stage silicification. Despite the absence of local burial history data, it is reasonable to consider the maximum burial depth (~ 4 km) of the Jurassic strata in the adjacent Luliang Uplift in the northern margin of Junggar Basin as the upper limit of QSF’s burial depth52. The corresponding pressure is ~ 90 MPa according to the lithostatic thermobaric gradient of 0.0226 MPa/m (Fig. 4a, Pmax)55, representing the upper pressure limit of the silicification process. Petrographic observations revealed that the interface between epitaxial quartz clusters and the siliceous wood substrate lacked clear signs of crystalline discontinuity or recrystallization (Fig. 2c‒f), indicating a relatively continuous crystallization process. Furthermore, no traces of secondary silicification were identified in the surrounding rocks and strata56. Therefore, the silicification in QSF is considered as a relatively successive process which occurred at relatively shallow burial depths. The obvious colour zoning of brownish red and white may be influenced by the existence of cellular structure or not (Figs. 1c and 2a). However, it was challenging to realize such continuous and long-term siliceous fluid throughout the burial process.

In general, the strength of wood precursors is relatively limited, and a compressive stress of 5–10 MPa was sufficient to induce significant deformation in the direction perpendicular to the texture57. Also, elongate and tangential fractures in the cell structure started to occur at an additional load of 1 MPa and ruptured cells gradually stratified till 2 MPa during radial compression58. In numerous wood modification attempts, silicification has been recognised as an effective method of enhancing the strength of wood, although the initial organic-template silicification has limited increment in enhancing the mechanical properties of wood6,59. In our samples, in both axially oriented silicified stumps and horizontally positioned silicified logs, significant deformation and typical cellular cracks have not been observed at either macroscopic or microscopic scales (Figs. 1 and 2). Therefore, the wood tissue should have been largely silicified before being buried to deep depths. It is important to note that while this study cannot definitively constrain the existence or P–T conditions of initial organic template silicification, this uncertainty does not invalidate the subsequent discussion. During the evolution of silicification, the early and final stages of silicification could be well-defined by the silicification of the bulk of wood tissue and the precipitation of epitaxial quartz, respectively, which should be discussed separately to determine the P–T range of the silicification process.

We suggest that the epitaxial quartz of the late silicification stage33 slowly crystallized in a miscible fluid at the minimum temperature range of 238–257 °C. Although it was uncertain whether the carbonaceous material inclusions were protogenetic or syngenetic, the thermal converting process was time-consuming, tending to support the protogenetic origin. Based on the idea that silicification was a relatively successive process without recrystallization, the peak silicification temperatures of 285 ± 30 °C measured by Raman thermometry appeared at the early stage. Thus, the peak temperatures and the fluid homogenization temperatures restricted the silicification process in a temperature range of 238–315 °C (Fig. 4b).

The maximum entrapment pressure of the final stage was limited to ~ 50 MPa by plotting the average peak temperature (285 °C) obtained from carbonaceous materials on the isochores (Fig. 4b, Pmax−A & Tmax−A). The minimum pressure of the late-stage homogeneous system is constrained by the fluid bubble point curve. The bubble point curve54 of the ternary CH4–H2O–NaCl system with similar components to that of our inclusions was plotted in P–T space (Fig. 4b). Its trend within the temperature range of 238–257 °C exhibits minimal variation with temperature, and indicates that the pressure required for phase homogenization was notably low (< 8 MPa). Due to the approximate fluid composition data and the bubble point curve, the phase behaviour of pure water could also be taken into consideration. Within this temperature range, the water system could transition from a phase-separated state to a homogeneous state at a pressure as low as ~ 4 MPa. At this pressure, the required depth of burial was only approximately 150 m. Considering the presence of surrounding tuffs (Fig. 1a)30, incipient silicification likely occurred shortly after the wood was buried by volcanic ash, lowering the pressure threshold to 0.1 MPa. Two possible mechanisms are proposed: (1) the high-temperature volcanic ash instantly vaporized water upon contacting with the surface; or (2) the ash acted as a seal, allowing hydrothermal fluids overflowing from volcanoes to penetrate beneath it and boil due to lower pressure. Thereby, the fossil site entered a vapor stability field shown in the P–T diagram (Fig. 4b), where accelerated wood degradation was counterbalanced by rapid silicification and preserved the wood cellular anatomy (Fig. 2). A successful experimental illustration of silica-enriched vapour silicification of wood has been reported by Läbe et al. (2012)11. According to the undeformed wood structure, the maximum pressure of the early stage is roughly limited to 2 MPa. As the volcanic eruption and subsequent burial proceeded, the elevated temperatures and vapour could generate significantly higher internal pressures within the fluid system. Consequently, the actual burial depth might be less than 150 m. Although the rate of early silicification remains uncertain, it can be remarkably rapid, i.e. within several days or several months, as evidenced by the steam silicification simulation and the silicified branch found in hot springs, respectively11,60.

The preservation of wood fossils encoded critical information about their taphonomic environments, as well as the physicochemical conditions of formation. The presence of CH4 and the lack of CO2 in the fluid inclusions imply that the silicification fluid possessed a reduced oxygen fugacity within the C-H-O ternary system61. Notably, the temperatures we obtained are higher than those typically used in experimental simulations of wood silicification7,8,11,22,23, challenging the common belief that the silicified wood forms at lower temperatures12,13. High temperatures have dual effects, promoting the thermal degradation of unstable organic components (such as cellulose) and accelerating the precipitation of silica by raising the effective diffusion coefficient as well as the solubility of silica in water7. Our results may explain the recurrent observations of charcoal-like appearances, the lack of delicate anatomical details and the absence of small twigs or cuticular materials) for wood fossils in QSF or other volcaniclastic environments (i.e., the Jehol Biota62,63. The alignment of mineral compositions, microstructures, in-situ occurrence and formation environments of the silicified wood from Qitai with those found in other volcanic settings underscores the broader applicability of our findings64,65,66,67,68.

This model explains fossil plant preservation in volcanic active palaeoenvironments and offers a new route to decode plant fossilization mechanisms in palaeoecological records. Crucially, conventional taphonomic interpretations based solely on sedimentary context (e.g., assuming low-temperature origins for fossils found in sedimentary sequences) may be misleading. Mineralogical and geochemical studies may overturn stratigraphic inferences and reinterpret the palaeoenvironment. Therefore, future studies need to incorporate multi-proxy analyses (e.g., fluid inclusions, silica textures) to critically examine plant fossil preservation.

Conclusion

The thermal model derived from the intersection of geothermal gradients and isochores yielded a P–T range that conflicted with the burial history of the Junggar Basin, thereby ruling out a deep burial origin for wood silicification of the QSF. The silicification temperature range, constrained by the peak temperatures of carbonaceous materials formed in the early stage and the homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions in late-stage quartz crystals, was limited to 238–315 °C. Based on the strength properties of wood and the presence of overlying tuff, pressure conditions were estimated at 0.1 − 50 MPa within a shallow burial origin associated with a spatio-temporal correlated volcanic event. These results, as well as the existence of CH4 in fluid inclusions, suggest that the silica precipitation continuously took place under relatively high-temperature, low-pressure and oxygen-limiting conditions, and might undergo a fluid transition from boiling to homogenization. Our findings challenge the common belief that silicified wood forms at low temperatures and contribute to a deeper understanding of fossil wood formation in volcanic environments.

Data availability

Tables 1 and 2 contain all data used for analysis and plots generation. All data used in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.22952.

References

Bardet, M. & Pournou, A. Fossil wood from the miocene and oligocene epoch: Chemistry and morphology. Magn. Reson. Chem. 53 (1), 9–14 (2015).

Witke, K., Gotze, J., Rossler, R., Dietrich, D. & Marx, G. Raman and cathodoluminescence spectroscopic investigations on permian fossil wood from Chemnitz—A contribution to the study of the permineralisation process. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 60 (12), 2903–2912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2003.12.045 (2004).

Shi, G. et al. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U–Pb dating of zircons. Cretac. Res. 37, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.014 (2012).

Matysová, P. et al. Alluvial and volcanic pathways to silicified plant stems (Upper Carboniferous–Triassic) and their taphonomic and palaeoenvironmental meaning. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 292 (1 – 2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.03.036 (2010).

Min, M. Z. et al. An excellent fossil wood cell texture with primary uranium minerals at a sandstone-hosted roll-type uranium deposit, NW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 17 (4), 233–239 (2001).

Yona, A. M. C., Žigon, J., Matjaž, P. & Petrič, M. Potentials of silicate-based formulations for wood protection and improvement of mechanical properties: A review. Wood Sci. Technol. 55 (4), 887–918 (2021).

Ballhaus, C. et al. The silicification of trees in volcanic ash - An experimental study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 84, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.01.018 (2012).

Leo, R. F. & Barghoorn, E. S. Silicification of wood. Botanical museum leaflets. Harv. Univ. 25 (1), 1–47 (1976).

Luthardt, L. et al. A new U–Pb Zircon age and a volcanogenic model for the early permian Chemnitz fossil forest. Int. J. Earth Sci. 107, 2465–2489 (2018).

Murata. Volcanic Ash as a source of silica for the silicification of wood. Am. J. Sci. 238 (8), 586–596 (1940).

Läbe, S., Gee, C. T., Ballhaus, C. & Nagel, T. Experimental silicification of the tree fern Dicksonia Antarctica at high temperature with silica-enriched H2O vapor. Palaios 27 (11), 835–841. https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2012.p12-064r (2012).

Perry, C. C. Silicification: The processes by which organisms capture and mineralize silica. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 54 (1), 291–327 (2003).

Mustoe, G. E. Silicification of wood: An overview. Minerals 13 (2), 206 (2023).

Chi, G., Diamond, L. W., Lu, H., Lai, J. & Chu, H. Common problems and pitfalls in fluid inclusion study: A review and discussion. Minerals 11 (1), 7 (2020).

Shi, G., Tropper, P., Cui, W., Tan, J. & Wang, C. Methane (CH4)-bearing fluid inclusions in the Myanmar jadeitite. Geochem. J. 39 (6), 503–516 (2005).

Beyssac, O., Goffé, B., Chopin, C. & Rouzaud, J. Raman spectra of carbonaceous material in metasediments: A new geothermometer. J. Metamorph. Geol. 20 (9), 859–871 (2002).

Kouketsu, Y. et al. A new approach to develop the R Aman carbonaceous material geothermometer for low-grade metamorphism using peak width. Isl. Arc. 23 (1), 33–50 (2014).

Buseck, P. R. & Beyssac, O. From organic matter to graphite: Graphitization. Elements 10 (6), 421–426 (2014).

Wopenka, B. & Pasteris, J. D. Structural characterization of kerogens to granulite-facies graphite: Applicability of Raman microprobe spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. (1993). 78(5 – 6), 533 – 557.

Rahl, J. M., Anderson, K. M., Brandon, M. T. & Fassoulas, C. Raman spectroscopic carbonaceous material thermometry of low-grade metamorphic rocks: calibration and application to tectonic exhumation in Crete, Greece. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 240 (2), 339–354 (2005).

Song, H. et al. The role of graphite in the formation of unconformity-related uranium deposits of the Athabasca Basin, canada: A case study of Raman spectroscopy of graphite from the world-class Phoenix uranium deposit. Am. Mineral. 107 (11), 2128–2142 (2022).

Drum, R. W. Silicification of betula Woody tissue in vitro. Science 161 (3837), 175–176 (1968).

Götze, J., Möckel, R., Langhof, N., Hengst, M. & Klinger, M. Silicification of wood in the laboratory. Ceram. Silikáty. 52 (4), 268–277 (2008).

Hill, C., Altgen, M. & Rautkari, L. Thermal modification of wood—A review: Chemical changes and hygroscopicity. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 6581–6614 (2021).

Li, C. Protection and development of Qitai silicified wood & dinosaur National geopark in Xinjiang based on RMP analysis. Resour. Ind. 14 (3), 118–122 (2012). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Bodnar, R. Revised equation and table for determining the freezing point depression of H2O-NaCl solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 57 (3), 683–684 (1993).

Bakker, R. J. Package FLUIDS 1. Computer programs for analysis of fluid inclusion data and for modelling bulk fluid properties. Chem. Geolo. 194 (1–3), 3–23 (2013).

Beyssac, O. et al. On the characterization of disordered and heterogeneous carbonaceous materials by Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 59 (10), 2267–2276 (2003b).

Vincent, S. J. & Allen, M. B. Sedimentary record of mesozoic intracontinental deformation in the Eastern Junggar Basin, Northwest china: response to orogeny at the Asian margin. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 194, 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1130/0-8137-1194-0.341 (2001).

Xu, X., Clark, J. M., Eberth, D. A. & Currie, P. J. The Shishugou fauna of the Middle–Late jurassic transition period in the Junggar basin of Western China. Acta Geol Sin. (English Edition). 96 (4), 1115–1135 (2022).

Trümper, S. et al. Late palaeozoic red beds elucidate fluvial architectures preserving large Woody debris in the seasonal tropics of central Pangaea. Sedimentology 67 (4), 1973–2012 (2020).

Saminpanya, S., Ratanasthien, B., Jatusan, W., Limthong, R. & Amsamarng, T. Mineralogy, geochemistry, and petrogenesis of the world’s longest petrified wood. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks. 12 (1), 37–62 (2024).

Mustoe, G. E. Mineralization of fossil wood with macrocrystalline quartz: A microscopic investigation. Minerals 15 (3), 225 (2025).

Dong, G., Morrison, G. & Jaireth, S. Quartz textures in epithermal veins, Queensland – Classification, origin and implication. Econ. Geol. 90 (6), 1841–1856 (1995).

Schmatz, J. & Urai, J. L. The interaction of migrating grain boundaries and fluid inclusions in naturally deformed quartz: A case study of a folded and partly recrystallized quartz vein from the Hunsrück Slate, Germany. J. Struct. Geol. 33 (4), 468–480 (2011).

Goldstein, R. H. Fluid inclusions in sedimentary and diagenetic systems. Lithos 55 (1–4), 159–193 (2001).

Liu, W. Q. & Shi, G. H. Thermometric data of silicified wood in Qitai, China. Sci. Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.22952 (2025).

Luque, F. et al. Deposition of highly crystalline graphite from moderate-temperature fluids. Geology 37 (3), 275–278 (2009).

Pasteris, J. D. Causes of the uniformly high crystallinity of graphite in large epigenetic deposits. J. Metamorph. Geol. 17 (6), 779–787 (1999).

Cesare, B. Graphite precipitation in C–O–H fluid inclusions: closed system compositional and density changes, and thermobarometric implications. Contrib. Mineral. Pet. 122 (1), 25–33 (1995).

Dodd, M. S. et al. Widespread occurrences of variably crystalline 13C-depleted graphitic carbon in banded iron formations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 512, 163–174 (2019).

Kiran, S., Satish-Kumar, M., Nakamura, Y. & Hokada, T. Comparison between Raman spectra of carbonaceous material and carbon isotope thermometries in low-medium grade meta-carbonates: Implications for Estimation of metamorphic temperature condition. Precambrian Res. 374, 106656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2022.106656 (2022).

Lepland, A., Van Zuilen, M. & Philippot, P. Fluid-deposited graphite and its Geobiological implications in early archean gneiss from Akilia. Greenl. Geobiol. 9 (1), 2–9 (2011).

Satish-Kumar, M. Graphite-bearing CO2-fluid inclusions in granulites: Insights on graphite precipitation and carbon isotope evolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69 (15), 3841–3856 (2005).

Ziegenbein, D. & Johannes, W. Graphite in C–H–O fluids: an unsuitable compound to buffer fluid composition at temperatures up to 700°C. Neues Jahrbook Mineral. Monashefte 7, 289–305 (1980).

Franklin, R. E. Crystallite growth in graphitizing and non-graphitizing carbons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Seri. A Math. Phys. Sci. 209 (1097), 196–218 (1951).

Li, Y., Quan, X. & Shi, G. Gemological characteristics of silicified wood in Qitai, Xinjiang and Bagan, Myanmar. J. Gemstones Gemol. 18 (2), 26–33 (2016). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Aoya, M. et al. Extending the applicability of the Raman carbonaceous-material geothermometer using data from contact metamorphic rocks. J. Metamorph. Geol. 28 (9), 895–914 (2010).

Mori, H., Mori, N., Wallis, S., Westaway, R. & Annen, C. The importance of heating duration for Raman CM thermometry: Evidence from contact metamorphism around the great Whin sill intrusion, UK. J. Metamorph. Geol. 35 (2), 165–180 (2017).

Beyssac, O., Brunet, F., Petitet, J. P., Goffé, B. & Rouzaud, J. N. Experimental study of the microtextural and structural transformations of carbonaceous materials under pressure and temperature. Eur. J. Mineral. 15 (6), 937–951 (2003a).

Qiu, N., Zhang, Z. & Xu, E. Geothermal regime and jurassic source rock maturity of the Junggar Basin, Northwest China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 31 (4 – 6), 464–478 (2008).

Hu, D., Rao, S., Wang, Z. T. & Hu, S. B. Thermal and maturation history for carboniferous source rocks in the Junggar Basin, Northwest China: Implications for hydrocarbon exploration. Pet. Sci. 17, 36–50 (2020).

Wang, Q. C. et al. Overpressure origins and evolution in deep-buried strata: A case study of the jurassic Formation, central Junggar Basin, Western China. Pet. Sci. 20 (3), 1429–1445 (2023).

Mao, S., Hu, J., Zhang, D. & Li, Y. Thermodynamic modeling of ternary CH4 – H2O–NaCl fluid inclusions. Chem. Geol. 335, 128–135 (2013).

Osborne, M. J. & Swarbrick, R. E. Mechanisms for generating overpressure in sedimentary basins: A reevaluation. AAPG Bull. 81 (6), 1023–1041 (1997).

McKnight, D. M. Fluvial sedimentology of an Upper Jurassic petrified forest assemblage, Shishu Formation, Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 79, 1 –9 (1990).

Zhong, W. et al. Multi-scale finite element simulation on large deformation behavior of wood under axial and transverse compression conditions. Acta. Mech. Sin. 37, 1136–1151 (2021).

Ando, K. & Onda, H. Mechanism for deformation of wood as a honeycomb structure I: Effect of anatomy on the initial deformation process during radial compression. J. Wood Sci. 45, 120–126 (1999).

Mai, C. & Militz, H. Modification of wood with silicon compounds, inorganic silicon compounds and sol-gel systems: A review. Wood Sci. Technol. 37, 339–348 (2004).

Hellawell, J. et al. Incipient silicification of recent conifer wood at a Yellowstone hot spring. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 149, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.10.018 (2015).

Huizenga, J. M. Thermodynamic modelling of a cooling C–O–H fluid–graphite system: implications for hydrothermal graphite precipitation. Miner. Depos. 46, 23–33 (2011).

Zhou, Z., Barrett, P. M. & Hilton, J. An exceptionally preserved lower cretaceous ecosystem. Nature 421 (6925), 807–814 (2003).

Zhou, Z. The Jehol Biota, an early cretaceous terrestrial Lagerstätte: New discoveries and implications. Natl. Sci. Rev. 1 (4), 543–559 (2014).

Falaschi, P., Grosfeld, J., Zamuner, A. B., Foix, N. & Rivera, S. M. Growth architecture and silhouette of jurassic conifers from La matilde Formation, Patagonia, Argentina. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 302 (3–4), 122–141 (2011).

Ghoshmaulik, S. et al. Triple oxygen isotopes in intertrappean fossil woods: Evidence of higher tropical rainfall during Deccan volcanism. Chem. Geol. 634, 121599 (2023).

Pe-Piper, G., Piper, D. J. W., Zouros, N. & Anastasakis, G. Age, stratigraphy, sedimentology and tectonic setting of the sigri pyroclastic formation and its fossil forests, early Miocene, Lesbos, Greece. Basin Res. 31 (6), 1178–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/bre.12365 (2019).

Rossler, R. et al. A snapshot of an early permian ecosystem preserved by explosive volcanism: New results from the Chemnitz petrified Forest, Germany. Palaios 27 https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2011.p11-112r (11–12), 814–834 (2012).

Mustoe, G. E. & Dillhoff, T. A. Mineralogy of miocene petrified wood from central Washington state. USA Miner. 12 (2), 131 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to H. X. Chu and X. G. Li for their kind support on fluid inclusion microthermometry.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42273044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. performed the data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. W.L., G.S., R.B. and A.J. conceptualized and edited the manuscript. T.H. and Y.Y. helped for sample preparation and methodology. W.L., G.S., Z.Z., L.Q., X.L., X.Q. and Y.Y. went for field investigation and sample collection. All authors provided critical feedback and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Shi, G., Zhou, Z. et al. High-temperature wood silicification: constraints from fluid and carbonaceous inclusions in quartz from Qitai, NW China. Sci Rep 15, 42961 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27072-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27072-z