Abstract

Studies show membrane bioreactor (MBRs) remove microplastics (MPs) effectively, yet their impacts on fouling, sludge, and microbes remain unclear. Findings vary, few investigations exist, and simplified conditions restrict applicability, highlighting the need for more robust, realistic research on wastewater treatment systems. In this study, the effect of MPs on MBR treating simulated urban wastewater was investigated by evaluating chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal and membrane fouling by adding polyvinyl chloride microparticles (PVC-MPs) into synthetic feed wastewater. The average particle size of MPs was 6.69 ± 4.2 µm. At steady state, the COD removal was 84.76 ± 4.27% and 92.48 ± 5.62% for MBR and MPs-MBR, respectively. The presence of MPs in the MBR led to a ca. 16 and 35% reduction in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and soluble microbial products (SMP) content of the sludge cake layer, respectively. Furthermore, the average permeate flux of the MPs-MBR was 48% higher, which was attributed to the properties of the sludge. The presence of MPs had no adverse effect on sludge settleability. The total membrane fouling resistance in the MPs-MBR was lower (1.85 × 1012 1/m) than MBR (3.21 × 1012 1/m). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) micro images confirmed the presence of fewer fouling agents on the fouling layer of the MPs-MBR. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and excitation-emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy analyses confirmed the lower intensity of proteins/carbohydrates functional groups in the cake layer of MPs-MBR, and no functional groups related to PVC-MPs were detected in the effluent from the MPs-MBR. Overall, it can be concluded that MPs were effectively retained by the membrane without adverse effect on membrane fouling behaviour.

Articlehighlights

-

First study of MBR fouling by PVC microplastics in simulated urban wastewater.

-

The ultrafiltration membrane retained all MPs in the MBR mixed liquor effectively.

-

MBR fouling was not worsened by MPs and showed slight improvement in flux behavior.

-

EPS/SMP adsorption by PVC-MPs and larger sludge flocs led to reduced fouling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) have long been identified as a global water pollutant. This type of pollution poses a worldwide risk, impacting not only marine ecosystems but also surface water, sediments, the atmosphere, soil, food sources, and drinking water. The sources of MPs include primary (the release of fine plastic particles directly from personal care items) and secondary (larger plastic items)1,2. Primary MPs are deliberately produced and incorporated into various consumer and industrial goods, including items like cosmetics and personal hygiene products3,4. In contrast, secondary MPs form unintentionally as larger plastic objects, such as fishing nets, bottles, bags, and food packaging, break down over time due to mechanical, chemical, or biological factors5,6. Additionally, synthetic textiles like nylon and acrylic release fibers during washing, which then make their way into aquatic environments via wastewater systems7,8. The most common plastics found in wastewater include polyamides (PA), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polycarbonate (PC), polyethylene (PE), polyester (PES), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET)9. PVC is among the most prevalent plastics globally, commonly found in construction materials, packaging, and household items. Its widespread use, combined with its tendency to fragment into MPs and persistence in the environment, contributes significantly to MPs pollution10,11.

Laboratory experiments on MPs have shown various effects on marine animals, including altered swimming behavior, increased mortality, and DNA damage. Additionally, there is a risk for humans who may consume species contaminated with MPs or the chemicals released from these particles. consequently, MPs removal has gained increasing attention12,13. Due to their small size (1 µm to 5 mm) and density (0.92–0.97 g/cm3), MPs are easily suspended in water and transported by wind or water currents. Research has shown that significant quantities of MPs are found in foods, including dairy products, meat, seafood, salt, and vegetables14,15.

Therefore, investigating the performance of different treatment technologies in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and their removal mechanisms is essential to reduce the number of MPs entering aquatic ecosystems16,17. In primary treatment, processes such as screening, sand filtration, and primary clarification can retain most of the MPs in the influent. Advanced tertiary treatment technologies can increase MPs removal efficiency to 95%9,18. MPs with different particle sizes have varying effects on wastewater and sludge treatment due to varying surface area, reactivity, mobility, bioavailability, and interaction with microorganisms19,20. Biological treatment methods, such as conventional activated sludge (CAS) and MBRs, are cost-effective and environmentally safe technologies for MPs removal from wastewater in recent times21,22,23. Among various physical, chemical, and biological wastewater treatment methods, the membrane bioreactor (MBR) systems offer the highest treatment efficiency due to the high microbial population near the membrane surface, ensuring complete pollutant removal before filtration through the membrane24,25,26. Moreover, the MBR systems have significant advantages, including excellent effluent quality, low sludge production, and operational flexibility27,28,29. MBR offers high flexibility and a combination of different processes, such as coagulation/flocculation30,31, adsorption32,33, and advanced oxidation processes34,35,36 with MBR has been reported to improve its performance. One of the main disadvantages of MBRs is membrane fouling and a gradual decline in permeate/effluent flux. This leads to more energy demand and costly physical/chemical cleaning procedures37,38,39. Previous studies have attributed fouling in MBRs primarily to soluble microbial products (SMP) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which serve as structural materials for biofilms, flocs, and mixed sludge25,31.

In a long-term study by Bayo et al.12, both the MBR system and rapid sand filtration demonstrated effectiveness in eliminating MPs from municipal wastewater, achieving removal rates of 79.01 and 75.49%, respectively. But the difference in performance between the two techniques was not statistically significant. Both technologies demonstrated higher efficacy in removing particulate MPs over fibers and effectively reduced the size of MPs, particularly fibers. In another study, Bella et al.40 examined sludge from WWTPs using CAS with and without primary clarification and MBR systems. MBR sludge had the highest concentration of MPs (ca. 86,000 MPs/kgdry sludge), with a more diverse polymer profile and shape distribution, underscoring sludge as a potential environmental reservoir of MPs and raising concerns about its management. This is further corroborated by Gorbacho et al.41, who reported high MPs concentrations in MBR influent and sludge, though MBRs achieved a remarkable 99.69% removal rate, especially when supplemented with clarification and sand filtration steps. Their findings also highlighted fragments and fibers as dominant MPs types and pointed to the critical role of process stages/design in minimizing MPs emissions. From a membrane performance perspective, Ghasemi et al.14 utilized the magnetic resonance imaging technique to investigate MP-induced fouling in ultrafiltration (UF) hollow fiber membranes. MPs alone caused minimal fouling and were easily removed with hydraulic cleaning, whereas alginate-induced fouling required chemical treatment. Interestingly, the combination of MPs and alginate created more complex fouling patterns but was more effectively cleaned hydraulically, demonstrating the complex role MPs can play in fouling dynamics. Similarly, Lares et al.14 reported that a WWTP combining CAS and a pilot-scale MBR achieved a 98.3% overall MPs removal rate, with MBRs outperforming CAS in final effluent quality. Still, both systems discharged some MPs, indicating the need for further refinement. Li et al.42 investigated MBRs for treating simulated surface water contaminated with synthetic PVC-MPs (< 5 μm), which were added at a rate of 10 particles/L daily in the feed water. They found that while organic and ammonia removal remained high, MPs temporarily inhibited system performance and increased membrane fouling, including irreversible forms. However, microbial communities remained stable, and bio-carrier (polyvinyl alcohol gel) adsorption aided MPs rejection. Wang et al.13 provided insights into the long-term accumulation of PP-MPs in MBRs, highlighting how the concentration of MPs influences microbial activity, SMP/EPS secretion, and membrane fouling behavior. Higher MPs levels even mitigated fouling due to changes in microbial communities. Finally, Yi et al.43 evaluated the effects of PET-MPs on MBR sludge. While biological removal was unaffected, PET accumulation worsened settleability, dewaterability, and microbial health. EPS levels rose, and TMP build-up slowed, likely due to physical scouring by MPs. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that while MBRs are highly effective at removing MPs, their presence can still affect membrane fouling, sludge properties, and microbial communities, highlighting the need for integrated approaches to optimization and risk mitigation in wastewater treatment. However, the role of MPs in fouling remains controversial: some studies report that MPs exacerbate fouling, others suggest they alleviate it, and still others find negligible effects. Given the novelty of this research area, only a limited number of studies are available, and more robust experimental evidence is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn. In addition, many existing studies use simplified conditions, such as single-size MPs without realistic size distributions or unrealistically low MP concentrations, which further limit their applicability to real-world scenarios.

Therefore, this study aims to address an existing research gap by systematically evaluating the impact of PVC-MPs on membrane fouling behavior in MBR systems. Unlike previous works that focused solely on MPs removal efficiency, with low MPs concentrations, or single-size MPs, or unrealistic spherical/bead shape/morphology, this research investigates how PVC-MPs, with a realistic size distribution and irregular shapes, interact with the sludge matrix, influence biofoulant secretion (EPS and SMP), and alter the membrane fouling mechanism. Key innovations highlighted in this work include an in-depth analysis of the MPs removal performance, membrane fouling monitoring, and membrane autopsy of the MBR systems in the presence of MPs at bench scale for treatment of simulated urban wastewater. PVC-MPs were synthetically introduced into simulated wastewater. The outcomes provide novel insights into the dual role of MPs as both potential pollutants and contributors to improved sludge properties, highlighting an unexpected but potentially beneficial effect of MPs presence in MBRs. Given the modular nature of MBRs with high scale-up potential, the study advocates for scaled-up studies including real-world treatment of domestic and industrial wastewater and evaluating the long-term effect of MPs accumulation inside MBR medium on the microorganism’s consortium and bioactivity.

Materials and methods

Deionized (DI) water with a conductivity of 2 µS/cm was utilized as needed during experimental procedures. All analytical-grade chemicals were sourced from Merck (Germany). The sludge samples employed in the research were collected from the wastewater treatment facility in Sahand City, located in Tabriz, Iran. Its initial suspended solids concentration was approximately 2500 mg/L. To promote microbial growth and adaptation to the MBR environment, the sludge was fed with synthetic wastewater for one month. Molasses and urea were used as carbon and nitrogen sources for synthetic wastewater, respectively. The characteristics of the synthetic feed are presented in Table 1. PVC-MPs were produced by mechanically shredding a standard PVC water laboratory tubing (I.D. × O.D. 3/8 in. × 1/2 in, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) with the aid of a household blender. The fragmented particles were subsequently passed through a 500-mesh sieve (25 µm aperture) to obtain the desired size fraction. After sieving, the PVC-MPs were preserved in a tightly sealed glass container, kept in a dark environment, in order to minimize any changes to their physicochemical characteristics.

MBR system

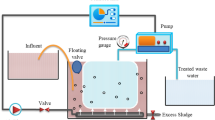

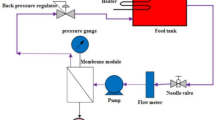

Two MBRs, made of glass, with identical dimensions (2 L volume), were used. Flat sheet membrane modules were connected to a vacuum pump and a vacuum Erlenmeyer flask to collect the permeate (Error! Reference source not found.). Wastewater feed was provided with gravity flow. An air diffuser was positioned at the base of the MBR units to provide oxygen, promote particle mixing, and generate shear forces along the membrane surface. One of the MBRs was used as a control (MBR) without any MPs, while PVC-MPs were added to the other reactor (MPs-MBR). 0.04 mg of PVC-MPs (which is equivalent to ca. 180,000 MPs, considering particle diameter of 6.69 µm, PSD median, assuming spherical shape, and a PVC density of 1.38 g/cm3) were added to the feed during each hydraulic retention time (HRT, 8 h). This amount is comparable to the values reported in the literature40,44,45. However, given that the SRT was 30 days, 66 mL portions of mixed sludge were discharged daily, resulting in an estimated 3% daily loss of some MPs. PVC-MPs level of 0.04 mg increases the likelihood of detecting MPs on the membrane surface using electron microscopy. Filtration was conducted using a vacuum pump, creating suction at a constant pressure of 0.12 bar. The UF membranes used were flat-sheet types composed of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), supplied by Ghesha Gostar (Iran), featuring a pore size of 0.01 µm and an active surface area of 12.5 cm2. Filtration was performed intermittently. Each filtration cycle comprises a repeating 2-min filtration (permeate collection) + 1-min rest (no permeate collection) operating cycle to reduce pump stress and prevent extensive fouling. During the rest period, the system’s vacuum pressure was maintained. Sampling was conducted approximately every 4 days from both the MBRs mixed sludge and the permeate for further analyses. The operational conditions of the MBRs and other relevant parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Analytical methods

Standard methods were employed to measure mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS), mixed liquor volatile suspended solids (MLVSS), total suspended solids (TSS), chemical oxygen demand (COD) using the closed reflux colorimetric technique, specific oxygen uptake rate (SOUR), and sludge volume index (SVI)46. The concentrations of EPS and SMP, along with their protein and polysaccharide components, were measured using a modified heat extraction technique25. A 6705 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Jenway, UK) was used to perform ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometric analysis. Particle size distribution (PSD) was assessed with an Analysette 22 NanoTec instrument (FRITSCH, Germany), which measured particles ranging from 0.01 to 1000 µm. Excitation Emission Matrix (EEM) spectra were obtained using an LS55 luminescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA), producing 3D fluorescence data with 5 nm intervals across excitation wavelengths of 200–400 nm and emission wavelengths of 200–600 nm. The size and structure of mixed sludge flocs in the MBR systems were examined under a 200 × magnification using a YS2-T optical microscope (Nikon, Japan). To identify functional groups in MPs, cake layer sludge, and MBR effluent, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was conducted using a TENSOR 27 instrument (Bruker, Germany). For sample preparation, the membrane surface was rinsed with DI water after treatment, and a portion of the recovered cake sludge was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting solid was oven-dried at 55 °C for 48 h. To investigate the morphology of the membrane’s cake layer, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed with a MIRA3 FEG-SEM system (Tescan, Czech Republic) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Prior to imaging, membrane samples (1 × 1 cm) were cut from each MBR and coated with gold.

Evaluation of membrane fouling

Initially, the pure water flux of the unmodified membranes was determined by applying a vacuum pressure of 0.12 bar. Water permeation was monitored until a stable flow rate was achieved, which was recorded as the initial flux (J₀). After 50 days, it was removed from the module and placed again in an MBR filled with DI water to measure the pure water flux after fouling, referred to as J1. Then, the membrane was physically cleaned with a sponge and placed back in DI water to measure the pure water flux again, referred to as J2. Finally, the membrane was chemically cleaned using 0.1 wt% NaOH, and the pure water flux was measured again, which is referred to as J337.

Membrane fouling resistance is calculated according to Eq. (1):

The total filtration resistance (RT) is composed of several components. These include the membrane’s inherent resistance (Rm), resistance arising from fouling (Rf), cake layer buildup (Rc) on the membrane surface, and pore blockage (Rp) within the membrane structure. All resistances are expressed in units of m⁻1. The above resistances are calculated based on Eqs. (2), (3), (4), (5) and (6):

where μ is the viscosity of water at the operating temperature (Pa.s), and TMP refers to the transmembrane pressure (in this study, 0.12 bar)42,47.

Results and discussion

Wastewater treatment performance of MPs-MBR

According to Fig. 1, most MPs lie in the size range of 2–20 µm. Additionally, the average particle size obtained from the analysis was reported as 6.69 ± 4.2 µm. The presence of PVC-MPs in the permeate of both MBRs was investigated, and the TSS value of the permeate stream from both MBRs was negligible, which shows successful removal of PVC-MPs by the UF membranes utilized in the studied MBRs.

The MPs-MBR system achieves greater COD removal efficiency compared to the conventional MBR. The steady-state removal for the MBR was 84.76 ± 4.27%, whereas for the MPs-MBR, it was 92.48 ± 5.62% (Fig. S2). These results indicate that the addition of MPs does not disrupt bacterial activity. The slightly enhanced COD removal of MPs-MBR can be attributed to both the adsorption of organics by MPs (due to the large specific surface area of MPs and hydrophobic interactions) and the subsequent biodegradation of organics by microorganisms43,48. Studies in this area support this conclusion. For example, a study by Wang et al.13 investigated the presence of PP-MPs (average size: 500 µm) in municipal wastewater for 84 days in an MBR. The reported COD removal was 88 ± 5% for the MBR and approximately 91 ± 6% for the MPs-MBR (containing 5 g/L of PP-MPs). The SOUR value of the MBR system was 8.3 ± 0.4, while that of the MPs-MBR was 7.9 ± 0.5, indicating only a slight difference, which shows that the microbial activity of the MBR was not affected by PVC-MPs49.

Membrane fouling evolution of MPs-MBR

Figure 2 shows the flux values for both MBRs. The reduction in flux indicates an increase in membrane fouling and, consequently, the clogging of membrane pores. The results show that the flux of MBR is lower than MPs-MBR and exhibits a steeper decline. Moreover, the membrane flux without any sludge particles, only PVC-MPs, was recorded, which shows negligible flux reduction due to the presence of only PVC-MPs. The average flux of MBR was 142.33 mL/m2·h, while in the MPs-MBR, it was 210 mL/m2·h.

Based on the results of fouling analysis (Fig. 3a and b), the RT in the MBR was 6.04 × 1012 1/m, which was higher than that in the MPs-MBR: 3.38 × 1012 1/m. Additionally, the pore resistance in the MPs-MBR was 1.85 × 1012 1/m, which is significantly lower than MBR: 3.21 × 1012 1/m. This observation is attributed to the high concentration of organic foulants in MBR, which not only occupy the spaces between microbial cells in the cake layer but also penetrate the membrane pores. However, these data indicate that MPs significantly reduce the concentration of organic foulants in MPs/MBR. Moreover, irreversible fouling in both MBRs is mainly caused by the entrapment of proteins and fine particles that are adsorbed inside the membrane pores47.

It can be hypothesized that MPs particles help reduce membrane fouling by manipulating sludge properties. Findings by Chew et al.44, Liu et al.50, and Wei et al.51 show that potential membrane foulants, including both suspended solids and dissolved compounds, tend to form larger flocs in the presence of MPs. EPS (mainly comprised of hydrophobic proteins) serves as a cohesive medium, promoting agglomeration of the generally hydrophobic MPs and facilitating their incorporation into biofilms. The main mechanisms involve physical bridging, EPS scaffolding, and ionic or hydrophobic binding. At the same time, foulant deposition on the membrane surface is reduced due to the dynamic scouring effect explained by momentum transfer theory43,52. Additionally, due to their particle size exceeding membrane pore dimensions, MPs are retained by the membrane, as confirmed by findings in previous research16,53. To confirm the membrane fouling observations and the effect of PVC-MPs on sludge floc properties, including floc size and cake layer chemical composition, a series of experimental and instrumental analyses were performed.

Samples from the mixed sludge of MBRs were imaged with an optical microscope at different magnifications (Fig. 4). The sludge particles in the MPs-MBR were larger than those in the MBR. Moreover, the particle size of the MPs influences the dimensions of the flocs formed44. In the MPs-MBR system, sludge particles tend to aggregate more tightly due to EPS scaffolding and hydrophobic interaction, which leads to the formation of a biofilm around MPs13,44, resulting in larger and denser clusters, while in the conventional MBR, the sludge remains in smaller, more loosely distributed particles. Larger sludge flocs form a more porous cake layer, and this increased porosity directly contributes to reduced membrane fouling54,55. In a similar study aiming to monitor the effect of PET-MPs on MBR (ca. 4000 particles/L), Wei et al.51 observed that smaller bacterial flocs tend to merge into larger ones in the presence of MPs. With persistent shear forces and the continuous release and accumulation of EPS, these flocs gradually increase in size and density, eventually developing into granular bacterial flocs. The measured SVI values were 42.22 ± 5.67 and 44.44 ± 3.42 ml/g MLSS for the MBR and MPs-MBR, respectively. The slight increase in the SVI value of MPs-MBR could be attributed to the formation of larger flocs (based on microscopic images, Fig. 4) due to the presence of MPs56. Yi et al.43 observed a similar SVI increase and sludge floc size increase in the presence of PET-MPs (60 particles/L), and it was related to the reduction of floc zeta potential. While other studies have reported adverse effects of MPs on sludge settling and floc size19,43,51, no such negative impact was observed in this research.

Figure 5 show SEM micro images of clean and fouled membranes in MBR and MPs-MBR before physical cleaning, after physical cleaning, and after chemical cleaning (at different magnifications).

Figure 5 shows that the clean membrane had more and clearer pores. Figure 6 reveals denser fouling in the MBR, with more sludge particles observable. The presence of different sizes of PVC-MPs (Rough and irregular MPs lacking spherical and rounded shapes) is confirmed in Fig. 7 (green dashed squares). Also, larger sludge flocs are observed on the membrane used in the MPs-MBR (Fig. 7), with sludge particles concentrated around the MPs (green dashed squares) and fewer particles reaching the membrane surface. These results are consistent with the lower fouling resistance measured in this system (Fig. 3). Post-cleaning images show a clean membrane surface with no residual particles and no visible damage to the membrane structure compared to the neat membrane (Fig. 5).

In addition to the physical effect of MPs on sludge floc, and given that EPS and SMP are widely recognized in the literature as key contributor to membrane fouling, their concentrations, along with their components, polysaccharides and proteinaceous compounds, in the membrane sludge cake layer were experimentally quantified to elucidate MPs effect on biofoulants. These measurements were conducted using the washing solution from the sludge cake layer after the end of the filtration tests. According to Fig. 8, the SMPC in the MBR and MPs-MBR were 199 and 75.8 mg/L, respectively. The SMPP values were 121 mg/L (MBR) and 102.8 mg/L (MPs-MBR). Overall, SMPT, SMPC, and SMPP values in the MPs-MBR are lower than in the MBR. This may be due to the adsorption of proteins and polysaccharides onto the MPs due to the large specific surface area and hydrophobic interactions44,48. Wei et al.51 have shown that EPS from activated sludge readily adsorb onto PS microplastics. Among the three fractions, tightly bound EPS (TB-EPS) exhibited the strongest binding, followed by loosely bound EPS (LB-EPS) and soluble EPS (S-EPS). This hierarchy was attributed to the higher aromaticity and hydrophobicity of TB-EPS, which promoted π–π electron donor–acceptor interactions and hydrophobic associations with PS-MPs surfaces. These findings highlight the role of EPS composition in controlling the extent and mechanism of EPS–microplastic interactions57,58. Also, large biomass flocs attach to the MPs, which leads to a reduction of the SMP concentration by restricting their mobility13,57. SMP plays a major role in membrane fouling by occupying the gaps between microbial cells within the cake layer, thereby decreasing its porosity and contributing to pore blockage43. A similar pattern was observed for EPS, which tends to bind to the surface of MPs and is consequently removed from the MBR system during sludge discharge. With the adsorption of EPS, the concentration of EPS in the flocs also decreases, leading to a less compressible cake layer. Moreover, a high concentration of EPS (especially proteins) can increase sludge adhesion to the hydrophobic PVDF membrane13,19. Since the protein content in both MBRs is higher than that of carbohydrates, it can be concluded that proteins are the key contributors to membrane fouling43,59. Maliván et al.19 showed that the addition of PES, PA, PP, and PE-MPs (sized 0.3 to 5.6 mm) to MBRs also resulted in reductions in both SMPT and EPSP levels. Overall, the SMPT level in the MPs-MBR has decreased by 29.20%, and the EPST level has decreased by 16.22% in the MBR system compared to the MBR. In addition, some studies have reported that EPS/SMP levels increase due to external toxicity or stress50,52. This effect was not observed in MPs-MBR, which shows no toxicity effect due to the presence of PVC-MPs.

To verify the presence and attachment of biofoulants, specifically EPS and SMP, to MPs, a comprehensive analysis was conducted. This involved characterization using FTIR and EEM spectroscopy after experimentally measuring the content of EPS/SMP in the membrane surface cake layer. Figure 9 shows the FTIR spectra of the sludge cake layer and effluent of the MBR and MPs-MBR. Following functional groups are detected: 600–800 1/cm: alkyl halide (R–X), 2900–3500 1/cm: N–H and O–H groups (indicative of polysaccharides), 1055 and 1730 1/cm: Carboxyl groups (C = O), confirming the presence of polysaccharides, 1450, 1540, and 1650 1/cm: Amide groups I, II, and III, indicating protein presence60,61. Overall, the sludge mainly contained proteins, polysaccharides, aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, and humic substances, confirming the presence of EPS and SMP. PVC-specific peaks were absent in the effluent but present in the sludge cake, indicating MPs retention due to size exclusion. Moreover, the intensity of the peaks for the effluent of the MBR was larger than the MPs-MBR, which is consistent with the COD removal results.

The membrane sludge cake layer was analyzed by EEM spectroscopy to determine both the chemical composition and the relative abundance of proteins and polysaccharides, which are key contributors to biofouling (Fig. 10). Peak A (located at Ex: 330–350 nm/Em: 420–480 nm) is typically associated with humic organic matter. Peak B (located at Ex: 250–260 nm/Em: 380–480 nm) corresponds to humic- and fulvic-like substances. Peak C (located at Ex: 250–280 nm/Em: 280–350 nm) is attributed to tryptophan-like proteins, while Peak D (located at Ex: 220–240 nm/Em: 330–340 nm) represents aromatic proteins and other proteinaceous compounds25. The contour plots exhibit minimal shifts in peak positions, indicating that the presence of MPs has a negligible adverse impact on microbial bioactivity43,62. Furthermore, the EEM contour for the MPs-MBR displays slightly lower peak intensities, aligning with experimental measurements of SMP/EPS and FTIR analysis. These results collectively indicate that the fouling behavior of the MPs-MBR system was maintained, with evidence of modest improvement. Fig. S3 shows a graphical summary of the effect of MPs on MBR flux performance and the identified mechanism.

Conclusion

Given the widespread use of plastics worldwide, the removal of MPs from wastewater is a critical challenge. Although the performance of the MBR system is proven, the effect of MPs on its performance has not been evaluated thoroughly. In this study, the removal of PVC-MPs from synthetic wastewater and their effect on membrane fouling inside an MBR system were evaluated. MPs led to slightly better COD removal due to the adsorption of organics. Membrane flux in MPs-MBR was not affected by the MPs due to reduced SMP and EPS levels and increased size of sludge flocs. Lower protein and carbohydrate concentrations in the sludge cake layer of MPs-MBR were confirmed with EEM spectroscopy. Membrane fouling analysis revealed that pore fouling was the dominant mechanism in both MBRs, but the intensity was lower in the MPs-MBR. FTIR analysis confirmed no PVC-MPs in the effluent of the MPs-MBR. SEM analysis of the membrane surface in the MPs-MBR showed a porous cake layer with larger particles, which was consistent with fouling resistance measurements. The results of this study demonstrate that the MBR system is capable of removing MPs from wastewater. The presence of MPs did not adversely affect the fouling behavior of MBR systems and was associated with improved sludge properties. Future research could expand the current study by examining the concentration and abundance of MPs in real wastewater, the long-term effects of MPs accumulation on microbial activity, and the dynamics of microbial consortia. Additionally, the influence of MPs on broader wastewater characteristics, including nitrogen and phosphorus cycles alongside COD removal, should be investigated. The effects of PVC-MPs on microbial communities also warrant a more detailed analysis from both microbiology and microbial engineering perspectives.

Data availability

Data availability statement The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Napper, I. E. & Thompson, R. C. Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 112(1–2), 39–45 (2016).

Jabbar, A. et al. Oxygen plasma treatment to mitigate the shedding of fragmented fibres (microplastics) from polyester textiles. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 23, 100851 (2024).

Zhao, K., Li, C. & Li, F. Research progress on the origin, fate, impacts and harm of microplastics and antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 9719 (2024).

Loppi, S. et al. Accumulation of airborne microplastics in lichens from a landfill dumping site (Italy). Sci. Rep. 11(1), 4564 (2021).

Iñiguez, M. E., Conesa, J. A. & Fullana, A. Microplastics in Spanish table salt. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 8620 (2017).

Da Costa Filho, P. A. et al. Detection and characterization of small-sized microplastics (≥ 5 µm) in milk products. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 24046 (2021).

Osman, A. I. et al. Microplastic sources, formation, toxicity and remediation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21(4), 2129–2169 (2023).

Rodríguez-Barroso, R., et al., Microplastics in drinking water. Efficiency of treatment and distribution of a drinking water distribution cycle. Cleaner Engineering and Technology. p. 100972. (2025)

Poerio, T., Piacentini, E. & Mazzei, R. Membrane processes for microplastic removal. Molecules 24(22), 4148 (2019).

Zahmatkesh Anbarani, M. et al. Adsorption of tetracycline on polyvinyl chloride microplastics in aqueous environments. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 17989 (2023).

Campisi, L., La Motta, C. & Napierska, D. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), its additives, microplastic and human health: Unresolved and emerging issues. Sci. Total Environ. 960, 178276 (2025).

Bayo, J., López-Castellanos, J. & Olmos, S. Membrane bioreactor and rapid sand filtration for the removal of microplastics in an urban wastewater treatment plant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 156, 111211 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Effects of microplastics accumulation on performance of membrane bioreactor for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 287, 131968 (2022).

Ghasemi, S. et al. Impact of microplastics on organic fouling of hollow fiber membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 467, 143320 (2023).

Boonsong, P. et al. Contamination of microplastics in greenhouse soil subjected to plastic mulching. Environ. Technol. Innov. 37, 103991 (2025).

Liu, W. et al. A review of the removal of microplastics in global wastewater treatment plants: Characteristics and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 146, 106277 (2021).

Nguyen, P.-D. et al. Evaluation of microplastic removal efficiency of wastewater-treatment plants in a developing country ,Vietnam. Environ. Technol. Innov. 29, 102994 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. A critical review of control and removal strategies for microplastics from aquatic environments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(4), 105463 (2021).

Maliwan, T., Pungrasmi, W. & Lohwacharin, J. Effects of microplastic accumulation on floc characteristics and fouling behavior in a membrane bioreactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 124991 (2021).

Reddy, A. S. & Nair, A. T. The fate of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: An overview of source and remediation technologies. Environ. Technol. Innov. 28, 102815 (2022).

Judd, S., The MBR book: principles and applications of membrane bioreactors for water and wastewater treatment. (2010) Elsevier.

Cavanaugh, S. J. & Weidhaas, J. Response surface methodology for performance evaluation of insensitive munitions wastewater membrane filtration. Cleaner Eng. Technol. 12, 100603 (2023).

Pikl, J.R., et al., Microfibres and coliforms determination and removal from wastewater treatment effluent. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, p. 100806. (2024)

Goswami, L. et al. Membrane bioreactor and integrated membrane bioreactor systems for micropollutant removal from wastewater: A review. Journal of water process engineering 26, 314–328 (2018).

Gharibian, S. & Hazrati, H. Towards practical integration of MBR with electrochemical AOP: Improved biodegradability of real pharmaceutical wastewater and fouling mitigation. Water Res. 218, 118478 (2022).

Karimi, L. et al. Investigation of various anode and cathode materials in electrochemical membrane bioreactors for mitigation of membrane fouling. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(1), 104857 (2021).

Díaz, O. et al. Fouling analysis and mitigation in a tertiary MBR operated under restricted aeration. J. Membr. Sci. 525, 368–377 (2017).

Qi, B. et al. Resource recovery from liquid digestate of swine wastewater by an ultrafiltration membrane bioreactor (UF-MBR) and reverse osmosis (RO) process. Environ. Technol. Innov. 24, 101830 (2021).

Parchami, M. et al. Production of volatile fatty acids from agro-food residues for ruminant feed inclusion using pilot-scale membrane bioreactor. Environ. Technol. Innov. 38, 104193 (2025).

Esteki, S. et al. Application of an electrochemical filter-press flowcell in an electrocoagulation-MBR system: efficient membrane fouling mitigation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12(1), 111769 (2024).

Esteki, S. et al. Combination of membrane bioreactor with chemical coagulation for the treatment of real pharmaceutical wastewater: Comparison of simultaneous and consecutive pre-treatment of coagulation on MBR performance. J. Water Process Eng. 60, 105108 (2024).

Pourbakhsh, N., Hazrati, H. & Gharibian, S. Highly efficient humic acid removal by environment-friendly copper/aluminum double-layer hydroxide nano adsorbents. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22(8), 6557–6572 (2025).

Taheri, E. et al. Polyamidoamine-based graphene oxide nanoparticles as adsorbent for mitigation of fouling in electrochemical membrane bioreactor. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21(11), 7539–7552 (2024).

Gharibian, S., Hazrati, H. & Rostamizadeh, M. Continuous electrooxidation of Methylene Blue in filter press electrochemical flowcell: CFD simulation and RTD validation. Chem. Eng. Process. -Process Intensification 150, 107880 (2020).

Gharibian, S. et al. Homogenous Electro-Fenton degradation of phenazopyridine in wastewater using a 3D Printed filter-press flowcell: Optimization via response surface methodology. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 170, 106026 (2025).

Rostamizadeh, M., Jafarizad, A. & Gharibian, S. High efficient decolorization of Reactive Red 120 azo dye over reusable Fe-ZSM-5 nanocatalyst in electro-Fenton reaction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 192, 340–347 (2018).

Hazrati, H. & Shayegan, J. Influence of suspended carrier on membrane fouling and biological removal of styrene and ethylbenzene in MBR. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 64, 59–68 (2016).

Hassan, A., et al., Efficient ibuprofen removal using enzymatic activated ZIF-8-PVDF membranes. 23: 100824. (2024)

Karamouz, F. & Hazrati, H. Mitigation of fouling in membrane bioreactor using the integration of electrical field and nano chitosan adsorbent. Environ. Technol. Innov. 36, 103774 (2024).

Di Bella, G. et al. Occurrence of microplastics in waste sludge of wastewater treatment plants: comparison between membrane bioreactor (MBR) and conventional activated sludge (CAS) technologies. Membranes 12(4), 371 (2022).

Egea-Corbacho, A. et al. Occurrence, identification and removal of microplastics in a wastewater treatment plant compared to an advanced MBR technology: full-scale pilot plant. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11(3), 109644 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Performance evaluation of MBR in treating microplastics polyvinylchloride contaminated polluted surface water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 150, 110724 (2020).

Yi, K. et al. Long-term impacts of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics in membrane bioreactor. J. Environ. Manage. 323, 116234 (2022).

Chew, J. H. et al. Fouling behavior of nano/microplastics and COD, TOC, and TN removal in MBR: A comparative study. Water Environ. Res. 97(5), e70099 (2025).

Li, L. et al. Effect of microplastic on anaerobic digestion of wasted activated sludge. Chemosphere 247, 125874 (2020).

Association, A.P.H., Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Vol. 6. 1926: American public health association.

Pan, J. R. et al. Effect of sludge characteristics on membrane fouling in membrane bioreactors. J. Membr. Sci. 349(1–2), 287–294 (2010).

Ittisupornrat, S. et al. Microplastic contamination and removal efficiency in greywater treatment using a membrane bioreactor. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1519230 (2025).

Mohamadi, S., Hazrati, H. & Shayegan, J. Influence of a new method of applying adsorbents on membrane fouling in MBR systems. Water and Environment Journal 34, 355–366 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Effect of polypropylene microplastics on the performance of membrane bioreactors in wastewater treatment. Environ. Res. 269, 120837 (2025).

Wei, S. et al. Effect of polyethylene terephthalate particles on filamentous bacteria involved in activated sludge bulking and improvement in sludge settleability. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20762 (2023).

Ko, J.-H. et al. Effect of microplastic size on biofouling in membrane bioreactors. J. Water Process Eng. 69, 106664 (2025).

Kang, I.-J., Yoon, S.-H. & Lee, C.-H. Comparison of the filtration characteristics of organic and inorganic membranes in a membrane-coupled anaerobic bioreactor. Water Res. 36(7), 1803–1813 (2002).

Zhu, J. et al. Impacts of bio-carriers on the characteristics of cake layer and membrane fouling in a novel hybrid membrane bioreactor for treating mariculture wastewater. Chemosphere 300, 134593 (2022).

Bai, R. & Leow, H. Microfiltration of activated sludge wastewater—the effect of system operation parameters. Sep. Purif. Technol. 29(2), 189–198 (2002).

Pompa-Pernía, A. et al. Treatment of synthetic wastewater containing polystyrene (PS) nanoplastics by membrane bioreactor (MBR): study of the effects on microbial community and membrane fouling. Membranes 14(8), 174 (2024).

Zafar, R. et al. Unravelling the complex adsorption behavior of extracellular polymeric substances onto pristine and UV-aged microplastics using two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Chem. Eng. J. 470, 144031 (2023).

Lei, J. et al. Adsorption Characteristics between different sizes of microplastics and EPS fractions of anaerobic granular sludge. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 33(3), 2141–2148 (2024).

Arabi, S. & Nakhla, G. Impact of protein/carbohydrate ratio in the feed wastewater on the membrane fouling in membrane bioreactors. J. Membr. Sci. 324(1–2), 142–150 (2008).

Mashayekhi, F., Hazrati, H. & Shayegan, J. Fouling control mechanism by optimum ozone addition in submerged membrane bioreactors treating synthetic wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6(6), 7294–7301 (2018).

Sabalanvand, S. et al. Investigation of Ag and magnetite nanoparticle effect on the membrane fouling in membrane bioreactor. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 3407–3418 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Exposure to polyamide 66 microplastic leads to effects performance and microbial community structure of aerobic granular sludge. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 190, 110070 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Sahand University of Technology for supplying the necessary facilities and equipment that made this research possible.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatemeh Nasiri: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. Hossein Hazrati: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Validation, Conceptualization. Soorena Gharibian: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasiri, F., Hazrati, H. & Gharibian, S. Investigating the impact of PVC microplastics on membrane fouling behavior in MBR for enhanced wastewater treatment efficiency. Sci Rep 15, 42871 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27102-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27102-w