Abstract

Mycotoxin exposure contributes to adverse human health outcomes, however, data regarding validated human biomarkers of exposure are lacking. This study presents an integrated framework for the biomarker discovery and toxicokinetic characterization of mycotoxin in humans. The aim of the study is to identify new biomarkers, determine their toxicokinetic (TK) properties, and build an integrated data analysis workflow using machine learning (ML), whilst focusing on non- and minimally-invasive sampling strategies. Following sample collection and chemical analysis, obtained datasets are used for the computation of ML models. Probability-based techniques are employed to calculate specific boundaries in the multidimensional space and, in parallel, ML classification methodologies are evaluated to scrutinize controls from intervened volunteers. Furthermore, multivariate regression models are computed to study the correlation of potential biomarkers with mycotoxin dosages. Once biomarkers have been identified, data are fit using Bayesian methods to a population-TK model to estimate key parameters related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. This standardized framework allows the scientific community to identify and validate new mycotoxin biomarkers and related ADME-properties in both a precise and accurate manner. Although we developed the proposed trial for various different mycotoxins, due to ethical considerations, focus was set towards IARC group III-classified mycotoxins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycotoxins are toxic fungal secondary metabolites that contaminate a wide spectrum of essential foods worldwide, including staple crops consumed by the most vulnerable populations in low- and middle-income countries1. Although many filamentous moulds are toxigenic, the most important mycotoxin-producing genera are Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium2. One fungal species may produce numerous different mycotoxins, and the same mycotoxin may also be produced by different species. Eskola et al. (2020) estimated that between 60% and 80% of the world’s food crops are contaminated with mycotoxins3. Therefore, human mycotoxin exposure through dietary consumption is universal3,4,5.

Mycotoxins have the potential to contribute to a diversity of adverse human health outcomes6. The foremost toxic effects are carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, oestrogenicity, allergenic manifestations, reproductive disorders, immunosuppression, and dermal effects. Nevertheless, mycotoxins as a group cannot be classified according to their mode of action, toxicology, or metabolism, as these have a great diversity in physicochemical properties. The most common and pathologically-significant mycotoxins are aflatoxins (AF) (e.g., aflatoxin B1, AFB1), fumonisins (e.g., fumonisin B1, FB1), ochratoxins (e.g., ochratoxin A, OTA), trichothecenes (e.g., deoxynivalenol, DON), patulin (PAT) and zearalenone (ZEN)7,8,9. Certain mycotoxins - such as AFB1 - are predicted to become an even more important food safety issue globally, especially in a +2°C global average temperature scenario, which is the most probable of the climate change scenarios expected for the upcoming years10,11. Notably, a recent Advisory Group of scientists recommended priorities for the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs program during 2020-2024 and 2025-2029, and highlighted FB1, AF, ZEN, and PAT as agents for evaluation, respectively12,13.

The capability of conducting accurate exposure assessments of mycotoxins at the individual level is required to fully understand potential health consequences in humans. Specific well-characterized biomarkers in biological fluids (urine or blood) have been shown to predict relevant clinical outcomes across a variety of treatments and populations14. A challenge in biomarker-driven research is to identify, prove the relevance, and validate biomarkers14. To date, the research field on mycotoxin biomarkers of exposure & effect is still a poorly unexplored territory. The only validated mycotoxin biomarker, besides AFB1-lysine (serum albumin adduct) & FB115,16,17, was recently validated by our group for DON through a human toxicokinetic (TK) intervention study, namely DON-3 & 15-glucuronide (DON-3-GlcA & DON-15-GlcA), by the use of mass spectrometry (MS)18,19.

In the past decade, MS has played an important role in xenobiotic metabolite identification2,20. The use of high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) for metabolomics approaches is still an underutilized tool in mycotoxin biomarker research, although a great impact is expected from this technology. HRMS will enable the unravelling of unknown metabolites and metabolic pathways of mycotoxins, which will support researchers and public health officials in gaining insights on how to assess the associated health risks of mycotoxin exposure.

In recent years, the scientific community has aimed to evaluate all variables (predictors, features) simultaneously (i.e., in a multivariate way) when interpreting collected data21,22,23,24,25,26. This approach allows for extracting the most relevant information from datasets, mainly when large amounts of noisy or redundant data occur. Multivariate data analysis techniques (also known as chemometrics in the research fields of chemistry or, more generally, machine learning, ML) are divided into two main categories: (i) pattern recognition techniques and (ii) regression methods.

Pattern recognition models are subdivided into (i) unsupervised models (i.e., the information about the a priori knowledge of the instances under exam is not considered by the algorithms) and (ii) supervised/classification models (the a priori information/category labelling the instances under exam is an essential input of the algorithms). The most used unsupervised methodologies in ML are Principal Components Analysis (PCA)27 and cluster analysis (CA)26. Supervised/classification modelling techniques are grouped into discrimination and class modelling techniques. The latter models, like Soft Independent Modelling of Class Analogies (SIMCA)28 are considered ensemble models and assign the different instances to no classes, one class, or more than one class. In mycotoxin biomarker analysis, discrimination models such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)26 and Partial Least Squares – Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA)29 are employed to calculate specific boundaries in the multidimensional space that allow separating the different individuals within their corresponding classes. In parallel, several further distance-based and experience-based ML classification methodologies should also be evaluated to recognize control individuals from mycotoxin-treated volunteers30,31. Furthermore, the main goal of supervised regression/calibration modelling is to assess the relationships and the correlation occurring between a matrix X of predictors/variables and one or more responses contained in a matrix Y. Examples of supervised regression techniques include Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR)32, Principal Component Regression (PCR), and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R)33. The quality of the regression models can be expressed by metrics such as the Root Mean Square Error in Calibration (RMSEC). This (absolute) value quickly indicates the magnitude of the error. If cross-validation is performed, it is possible also to evaluate the Root Mean Square Error in Cross-Validation (RMSECV). Furthermore, suppose new independent objects are introduced into an external evaluation set to test the performance of the developed models. In that case, the Root Mean Square Error in Prediction (RMSEP) can also be calculated.

The metabolic profile reflects the functionality of kidneys, liver, and the gastrointestinal tract, which are the major physiological compartments involved in mycotoxins transformation, absorption, and excretion (ADME-principle)34,35,36. Once biomarkers have been identified, resulting data are integrated through the use of TK models to derive estimates of key ADME parameters, such as rates of gastrointestinal (GI) uptake, clearance by metabolism, and urinary excretion. For xenobiotics, hierarchical population-based Bayesian models have emerged as a state-of-the-art approach to account for inter-individual variation in ADME. However, surprisingly, it has yet to be applied in the context of mycotoxins37,38,39,40.

This study presents an integrated framework for the biomarker discovery and toxicokinetic characterization of mycotoxin in humans. Using both newly generated and previously validated results, it combines a standardized human intervention trial with different data analysis, including ML–based classification and regression, and hierarchical Bayesian TK modeling. The approach is designed for mycotoxins classified in IARC Group III, ensuring ethical feasibility while maintaining mechanistic relevance.

Special focus is laid on implementing non- and minimally-invasive sampling strategies. The generated data support the identification of novel biomarkers of exposure and the construction of robust TK models based on the metabolic profile. The harmonization of the experimental design improves both the repeatability and reproducibility of the experimental results obtained, whilst the coverage of different bio-matrices improves the model’s predictivity and highlights the superiority of multi-matrix approaches in biomarker detection, pathway elucidation, and future clinical purposes41.

Material and methods

Human intervention trial

The recruitment was aimed to enrol an adequate number of research volunteers to achieve robust and trustful results based on the specific research question(s). The procedures for the recruitment, along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a volunteer manual were detailed in the information brochure (IB), which was broadcasted with the invitation through a direct e-mail or delivered in person. Specific for mycotoxin intervention trials, people who suffered from kidney, liver, or bile diseases were excluded, as well as people who were taking medicinal drugs that affected the same organs (such as cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibitors) since the functionality of the compartments involved in the metabolism of mycotoxins might have been compromised. Furthermore, as mycotoxins have been demonstrated to pass through the placental barrier to the foetus or through breastmilk to the newborn, pregnant or breastfeeding women were excluded as well42,43,44,45,46. All the required template documents were lawfully legitimated agreeing to the enforced laws of the country where the trial is performed. Specifically, this trial was developed in compliance with Belgian and European legislation and the Declaration of Helsinki. The presented study design was approved on September 9th, 2020, by the Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital (UZGent, Ghent, Belgium) as an amendment to the original dossier B670201630414, approved on February 2nd, 2017. All the documents and the human intervention trial were approved by the Ethical Commission of the Organization of the Research Centre. The research volunteers who were interested to take part in the trial, were invited starting from February 2017 and again from June 2021 by the principal investigator (PI) to overview the study (no data will be collected at this point) (Supplementary Information - Document S1) at the Research Centre. Before entry the study, the implications of participation, and the required procedures were explained (Supplementary Information - Documents S3 and S4). After signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF) (Supplementary Information - Document S2), the eligible research volunteers were invited for an introductive meeting together with the supervising Medical Doctor (MD). During this meeting, more details were provided regarding the study. Participants were requested to fill in a sociodemographic questionnaire (Supplementary Information - Document S5) before receiving the sample collection material and the aqueous solution with or without mycotoxin depending on the group they were assigned (control or intervention). Participant assignment to one of the two groups was performed randomly using a randomization function. Given the typically small sample sizes in intervention studies, the random allocation was subsequently double-checked to ensure that the two groups were balanced in terms of sex, BMI, age, and number of participants, among others. Participants were not informed about their specific group allocation.

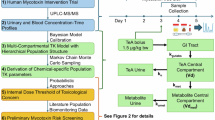

The intervention trial was designed to be minimally invasive and patient-friendly. All the procedures were executed at home in a time frame of five consecutive days as depicted in Figure 1. On days 1 and 2, the research volunteers were requested to avoid or limit the consumption of any food and drinks containing the mycotoxin investigated; this specific information was reflected in the volunteer manual. A list of foods with relative levels of mycotoxin contamination was provided by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) for multiple mycotoxins. However, an additional review of publications was performed to ascertain a mycotoxin-free diet. To control for this setting, a food diary (Supplementary Information - Document S6) was compiled during the 5-day trial by the volunteers to trace the consumption pattern as explained in the manual (Supplementary Information - Document S3). On day 3, the volunteers collected blank samples after awakening, followed by the consumption of the aqueous bolus solution with a dedicated amount of mycotoxin (ng/µg) calculated based on the declared body weight (bw, kg). The mycotoxin amount in the bolus did not exceed any health-based guidance value or safe exposure threshold established by a competent authority, such as the total daily intake (TDI, µg/kg bw/day) or threshold of toxicological concern (TTC, µg/kg bw/day)47. As most mycotoxin standard solutions are methanol/acetonitrile-based, the solution was first dried down with N2 to avoid any presence of organic solvents. The dry residue was then redissolved in 50µL of pure ethanol and diluted in 5mL of water. After ingestion, the volunteers started collecting urine, capillary blood, and/or faeces for the upcoming 48 hours. Urine void volume samples were collected using a graduated polypropylene measuring cup and an aliquot was transferred to a traditional plastic sample container with a screw cap. Faecal material was collected by the use of Fe-Col® paper ring (Alpha Laboratories, UK) and an aliquot was transferred to a plastic sample container with a screw cap. Capillary blood samples obtained from the fingertip using a BD Microtainer® lancet pen (Novolab, Belgium) were collected with 20 μL Volumetric Absorptive Micro samplers (VAMS) (Mitra®, Neoteryx, USA) according to a pre-defined sampling schedule (Supplementary Information - Document S7). Volunteers delivered the biological samples, food diary, and sampling collection schedule within 24 hours from the last sample collection to the research team for storage at −80°C upon analysis. While the capillary blood collected via VAMS® and the urine were directly stored in the biobank, the faeces were freeze-dried at −55°C for 24 hours before storage to quench bacterial activity, limit oxidative reactions and immobilize (non)-enzymatic reactions48. The weight of the samples was recorded before and after the freeze-drying process. Upon arrival at the research facility, all samples and materials were pseudo-anonymized by assigning unique codes to each volunteer and corresponding sample. This procedure ensured a double-blind study design.

Design of the 5-days human mycotoxin intervention trial. Created with BioRender.com and adapted from Visintin et al. (2023)49.

Outline and timing

Stage I: recruitment of the volunteers Timing ≈ 15–30 days

An invitation (Supplementary Information - Document S1) was sent to potential participants through direct e-mail along with the IB and Volunteer manual part I (Supplementary Information - Document S3).

The interested volunteers who meet the inclusion criteria specified in the IB to the Research Centre were invited to get an overview of the study and its implications (Supplementary Information - Documents S3 and S4). After this the volunteers signed the ICF (Supplementary Information - Document S2); without signed ICF, participation was not allowed.

An intake meeting was scheduled together with the supervising MD nominated for the trial. During this meeting more details were provided regarding the study and participants were required to fill in a sociodemographic questionnaire before receiving the aqueous solution with or without mycotoxin and the required sample collection material.

Stage II: preparation of the human TK trial Timing ≈ 48 hours

On day 1 and 2, the volunteers were required to avoid or limit the consumption of any food and drinks commonly contaminated with the mycotoxin administrated during the trial; this specific information was reflected in the instructions provided (Supplementary Information - Documents S3 and S4). To control for this setting, a food diary was kept during the 5-day trial to trace the consumption pattern (Supplementary Information - Document S6).

Stage III: self-execution of the human TK trial Timing ≈ 48 hours

On day 3, the volunteers collected blank samples after awakening: blank blood, blank urine, and blank stool (if possible). Next, the volunteers consumed an aqueous bolus solution with a dedicated amount of mycotoxin (ng) calculated based on the declared body weight (bw, kg).

After the mycotoxin intake, the volunteers were requested to start the collection of urine, capillary blood, and faecal material for exactly 48 hours and to log all collection times into the collection schedule (Supplementary Information - Document S7). For the blood collection via VAMS, the volunteers followed the time schedule of collection.

The volunteers were required to continue to avoid or limit the consumption of any food and drinks commonly contaminated with the mycotoxin administrated during the trial.

Stage IV: finalizing the human intervention trial Timing ≈ 24 hours

Volunteers visited the Research Centre one final time for the deposit of the collected samples and the written documents within 24 hours.

Sample analysis and data acquisition

Multiple methods were proposed for the extraction of mycotoxins from urine, blood, and faeces samples depending on the class of mycotoxins under investigation and the analytical technique used for the detection. In Supplementary Information - Document S8, a brief review discussing the most common extraction procedures is provided.

The most common analytical approaches for mycotoxins’ detection in human biomonitoring studies have been attributed to the metabolomics field which is a powerful tool to gain insights into identification of complex molecular mechanisms in biomedical research50. Targeted approaches based on LC-MS/MS, mostly tandem quadrupoles systems, are commonly used to quantify mycotoxins in the context of biomonitoring51. This approach focuses on the analysis of known metabolites, of which the absolute or relative quantity needs to be determined to answer the specific research question. The initial assumption is that the researcher knows a priori if the mycotoxin is metabolised and in which matrix the mycotoxin and its metabolites are excreted. Once the molecules of interest have been identified, the method is applied using external and internal standards (IS)50. The MS/MS systems for targeted analysis for the detection of mycotoxins are typically operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode52. This data acquisition modality provides a significant gain in both sensitivity and selectivity and allows the quantification of the compounds. Details about application and development of targeted and untargeted strategies for mycotoxins detection have been described extensively in the reviews of Arroyo-Manzanares et al. (2021)51 and Malachová et al. (2018)52. However, not all mycotoxins are commercially available as reference standards for human biomonitoring, and, as a result, interest in HRMS is increasing. More specifically, orbitrap and time-of-flight (TOF) mass analysers have emerged as the most convenient technique for mycotoxin detection, in some cases coupled with ion mobility spectrometry (IMS)51. Untargeted metabolomics allows the detection of thousands of different molecules in a single chromatographic run, yet the acquisition of a full metabolic profile is achieved at the expense of sensitivity53. Consequently, the compound identification and quantification in untargeted analysis remain challenging54.

Outline and timing

Stage I: storage of the samples Timing ≈ 24–48 hours

As soon as the biological samples were delivered to the Research Centre, they must be stored in the registered biobank at −80°C until the day of analysis. The capillary blood collected via VAMS and the urine were directly stored in the biobank. The Mitra® tips were eventually re-organized in Mitra® 96-autoracks or Eppendorf® tubes (2,500 µL). The faecal material underwent a lyophilization step for 24 hours before storage at −80°C. The sample, its location, and the correspondent ICF was registered in a dedicated and secure system to comply with the GDPR regulation. The stability of the compounds was investigated under storage conditions compatible with the trial to assure an accurate quantification.

Stage II: optimization of the extraction and analytical method for multi-mycotoxin detection Timing ≈ 2–4 weeks per method

Stage III: extraction and analysis of the samples Timing ≈ 24 hours

The quantification of the analytes was performed using an optimised and validated method employing matrix-matched calibration and an internal standard (13C-labelled or deuterated). Recovery and sensitivity of the method were crucial since the concentration of the biomarkers in biological samples is typically in the order of 0.05–100.05 ng/mL depending on the mycotoxin and its dose.

Data elaboration

Data elaboration depends greatly on the specific research question considered. Generally, it consists of several steps including the creation of a final dataset(s) integrating the metadata and results obtained, the development of a coding pipeline, if not already existent, and the data elaboration itself including creation of graphical and numerical output. The timing can vary greatly due to the interplay of these numerous variables with a minimum of 24/48 hours.

Biomarker identification

To facilitate the discovery of metabolites and biomarkers of exposure, samples collected during the TK trial are preferably analysed using an untargeted metabolomics approach. This approach was applied to the urinary samples collected during a human intervention trial performed for the investigation of tenuazonic acid (TeA) by Visintin et al. (2023)49. The consumption of a bolus containing the mycotoxin or water was followed by 48 hours of individual urinary samples collection from both the intervention group and control group. A simple dilute-and-shoot approach was employed for sample preparation49. The urinary polar metabolome was acquired using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS), possibly in both positive and negative ionization modes.

The raw data, obtained as.raw files, achieved from the analysis of samples, analytical standards, and blanks, were used to build a dataset by importing the raw profile data of the real samples in a software for alignment such as Progenesis QI55 (version 3.0, Waters®, Manchester, UK). The dataset is created by exporting as.csv file the chromatographic areas for each compound (identified by accurate m/z and rt) in each sample. In metabolomic experiments involving multiple samples, corresponding analytes in different samples must be mapped before conducting quantitative, comparative, or statistical analyses. The alignment of the runs was done by matching the chromatograms feature by feature through correspondence. The correspondence approach used by Progenesis QI version 3.0 (Waters®, Manchester, UK) consists of constructing a vector in the retention time direction that warps the content of the different runs and matching them the most closely to a given reference run. Data elaboration was performed using R56 (version 4.4.1, 2024-06-14) in Rstudio environment57. Orthogonal Partial Least Square Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) was used as a chemometric filtering tool on the urinary polar metabolome dataset. The OPLS-DA algorithm was applied using ropls package58 in R environment59,60 to select the most effective variables in classifying control and intervention samples and calculate the classification efficiency of the OPLS-processed and reduced datasets. A volcano plot was built for each dataset after calculating the log2 fold-change, and a p-value of each feature was corrected for the false discovery rate61. The top features were selected and used to build and cross-validate the final OPLS-DA model. The performances of the model in classification was evaluated by computing the cumulative R2X, R2Y, Q2, and RMSEE62,63. All the R codes are reported in the GitHub repository https://github.com/liavisintin/OPLSDA_TeA. Potential phase I and II metabolites were predicted in silico by the use of GLORY64 for the cytochrome P450 phase I metabolism, GLORYX65 for the phase II metabolism, and Compound DiscovererTM66 (version 3.3, ThermoFisher SCIENTIFIC®, Waltham, MA USA) for combination of phase I and II. During the comparison between the detected features and possible metabolites, the retention times were also compared with the retention time of the parent mycotoxin, to exclude cases of in-source fragmentation, isotopes, and/or adducts.

Biomarker selection and validation

Once biomarkers of exposure are known and reference standards are available, samples collected during the human intervention trial can be analysed for the quantification of the biomarkers. The samples were used to determine and validate the most effective biomarker by testing multiple discrimination and multivariate regression models. The dataset was obtained from the intervention trial conducted by Vidal et al. (2018)18 and further extended by Mengelers et al. (2019)19 for the investigation of DON metabolization. As previously mentioned, through the trial, Vidal et al. (2018)18 was able to validated one of the few mycotoxin biomarkers existent18,19. The study concluded that DON-15-GlucA is the major urinary metabolite of DON and confirmed its use as validated biomarker by comparison of the excreted amounts of the known metabolites.

In the current work, as alternative to the method used by Vidal et al. (2018)18, ML and Multivariate Data Analysis (MDA) models were applied to the same data to investigate the role of the different metabolites and define the best biomarker of exposure to DON. All R scripts can be found in the associated GitHub repository ( https://github.com/eugenioalladio/human-mycotoxin-UGent).

The recruited volunteers were divided in 2 groups: DON group (n=16) which received a bolus of DON at TDI of 1 µg/kg bw and control group (n=4) which received pure water. Overall, between 6 and 17 urine samples were collected from each volunteer within 24 hours from the intake. The urinary concentration of DON and its major urinary metabolites DON-3-GlcA and DON-15-GlcA were quantified via UHPLC-MS/MS in all the collected samples. The concentration values were then converted to mass excreted (ng) using the total urinary void volume recorded for each individual sample. For the computation of ML and MDA models, a final dataset (4 × 139) was prepared consisting of 139 urine samples per 4 features, i.e., DON dose and the amounts of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA recovered in urine. Supervised discrimination models, LDA and PLS-DA, were employed to discriminate volunteers from the DON and control group. In parallel, ML models such as k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN)30, Naïve Bayes (NB)67, Support Vector Machine (SVM)68, Decision Trees (DT)69, Random Forests (RF)70, and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)71 were tested to recognize control from DON volunteers. A benchmark comparison of all the computed models was made by evaluating the following classification metrics: sensitivity (DON volunteers correctly identified), specificity (control volunteers correctly identified), accuracy (volunteers correctly classified) and mean misclassification error (volunteers wrongly classified)72. Benchmarking comparisons were tested to evaluate different learning algorithms and investigate the information contained by identifying those models that perform best for a particular classification or regression task. Furthermore, multivariate regression models were computed to study the correlation of the collected variables, namely mass excreted of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA, with the DON dose taken by the study volunteers. The DON dose for the control group was set to zero. Multivariate linear regression (MLR)73, principal component regression (PCR)74, partial least squares regression (PLS-R)75, Artificial Neural Network (ANN)76, RF, k-NN, SVM, and XGBoost77 models were computed and a benchmark comparison was made by evaluating the goodness of prediction of DON dose in terms of the R2 determination coefficient, and the root mean square error (RMSE). All the ML models were cross-validated rigorously to obtain unbiased ML models and avoid misinterpretation of the results. A 5-times repeated 10-fold cross-validation strategy was used for all the evaluated classification and regression models. Autoscaling was used as a preprocessing strategy before computing the ML models. The benchmark was performed using R56 (version 4.4.1, 2024-06-14) in Rstudio environment57 and the mlr package78.

Toxicokinetic modelling

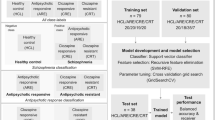

Once likely biomarkers have been identified, they can be used to estimate ADME parameters through the use of TK modelling. The overall components of the approach applied by Lu et al. (2023)79 are illustrated in Figure 2 and consist of a compartmental TK model (1); a Bayesian statistical model accounting for population variability, statistical errors, and prior parameter values (2); and a Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation to make posterior predictions after fitting the model to the data (3).

Components of a toxicokinetic modelling approaches for biomarkers in blood, urine, and faeces. A. Compartmental TK model. B. Bayesian statistical model accounting for population variability, statistical errors, and prior parameter value. C.Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation to make posterior predictions after fitting the model to the data. Adapted from Lu et al. (2023)79.

Because each mycotoxin has a unique metabolic profile, for illustration, we consider a “generic” mycotoxin model with a single metabolite, and samples collected in blood, urine, and faeces as described above.

The TK model consists of three internal compartments (i.e., GI tract, a compartment for the mycotoxin, and a compartment for the metabolite), and three external compartments (i.e., mycotoxin in faeces, mycotoxin in urine, and metabolite in urine). From the GI tract, there are two elimination pathways: excretion to faeces with rate kgutelim, and absorption to systemic circulation with rate kgutabs. From the mycotoxin body compartment there are also two elimination pathways: excretion to urine with rate ku and metabolism to the metabolite with rate kmet; the metabolite is henceforth excreted to urine with rate kumet. The ratio between the amount in the body and the concentration in blood is given by the volumes of distribution Vd and Vdmet for the mycotoxin and metabolite, respectively. All elimination rates have units of hr−1 and volumes of distribution have units of L/kg. In the example mycotoxin code provided, the following parameter transformations were used in order to facilitate calculation of key TK quantities (see below) and improve convergence:

-

Fgutabs = kgutabs/(kgutabs + kgutelim)

-

ktot = kmet + ku

-

kufrac = ku/(kmet + ku)

Moreover, all parameters were natural log-transformed for fitting.

The Bayesian statistical model is made up of three parts80. The first is a population variability model in which each of the TK model parameters is assumed to exhibit lognormal inter-individual variability, with a corresponding population geometric mean (GM) and geometric standard deviation (GSD). Second, a statistical model is specified for measurement and model errors in terms of the data likelihood function, which is also assumed to be lognormally distributed. Third, each parameter is given a prior distribution that is informed by a review of the literature for each mycotoxin. For instance, in the case of DON, prior distributions on estimates were based on in vitro data and inter-species scaling81.

The third component of the model is the actual model fitting using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation. The MCMC approach draws a sample along a Markov chain, which is constructed to have the posterior distribution as its long-run stationary distribution82,83,84. In this case, a hierarchical Metropolis-Hastings algorithms within the Gibbs sampler, was performed using GNU MCSim software (version 6.1.0)85,86,87 integrated in a R56 (version 4.4.1, 2024-06-14) pipeline developed in Rstudio environment57. Each iteration of the Markov chain generates a vector of parameters sampled from the parameter distributions and values of the posterior likelihood associated with that vector of parameters. The MCMC simulation thereby generates posterior (updated) parameter values at the population level as well as at the individual level. Convergence of the Markov chains to the posterior distribution is monitored using analysis of variance as described by Gelman et al. (1996)80. The Gelman and Rubin (1992) shrink factors (potential scale reduction factor, R), a ratio of an upper bound and a lower bound of the variance in the target distribution, is used to assess whether the independent MCMC chains have converged to a common distribution88. As multiple, independent chains move closer together toward the same distribution, the ratio declines to unity. A convergence diagnostic “R” of 1.2 or less has been proposed as a criterion for acceptable convergence89. Our previous model for DON required 4 chains with 50,000 samples in each chain to reach acceptable convergence, which took around 5 hours on a modern personal computer. Key TK quantities of interest are derived from the model parameters, including: the fraction absorbed (Fgutabs) = kgutabs/(kgutabs + kgutelim), the mycotoxin elimination half-life (T½) = ln (2)/(kmet + ku), the mycotoxin clearance (CL) = Vd x kmet, and the area under the concentration curve (AUC) = Dose x Fgutabs/CL. Additionally, with these parameters, dose can be reconstructed using excretion data consisting of total faecal excretion of the parent compound (Efaeces), total urine collection of the parent compound, (Utot), and total urine collection of the metabolite (Utotmet). Specifically, by mass balance, these totals must equal the total dose (D): D = Efaeces + Utotmet + Utot. Additionally the fraction absorbed can also be estimated: Fgutabs = (Utotmet + Utot)/D. Finally, the inter-individual variability in each of these TK quantities can be estimated using the posterior distributions for the GSD for each of the underlying parameters.

Results & discussion

Biomarker identification

The implementation of this approach using urinary samples from a human intervention trial investigating TeA has been published before49. In brief, following a single-dose intake, the average cumulative urinary excretion of TeA was 0.39 ± 0.22 over 13 hours. Following untargeted and suspect screening analyses, established OPLS-DA models effectively distinguished between intervention and control groups (accuracy: 0.88 for HESI+, 0.85 for HESI-), indicating TeA exposure significantly impacted metabolic pathways. A total of 122 potential biomarkers were identified, with in silico predictions suggesting 9 possible TeA metabolites including oxidized, N-alkylated, desaturated, glucuronidated, and sulfonated forms, confirming both phase I and phase II metabolism49.

Biomarker selection and validation

In the current work, ML and MDA models were applied to the data obtained by Vidal et al. (2018)18 to define the best biomarker of exposure to DON. Benchmarking comparisons of several classification and regression ML models were tested to evaluate different learning algorithms. The classification task involved the discrimination of control from DON volunteers by taking into account the urinary concentration levels of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA monitored over multiple time points. On the other hand, the regression task focused on evaluating the correlation of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA with the DON (or placebo) dose provided to the different volunteers. The classification benchmark provided satisfactory results in terms of accuracy, mean misclassification error, sensitivity, and accuracy for several ML models. The metrics’ results for the classification benchmark are graphically shown in Figure 3.

Bar plots showing the accuracy, mean misclassification error, sensitivity, and specificity values of the classification benchmark comparing deoxynivalenol (DON) volunteers versus control volunteers. The models tested were k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Partial Least Squares – Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), Naïve Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Trees (DT), Random Forests (RF), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost).

As it can be observed, different ML classification models provided metrics values close to 100% in terms of accuracy (k-NN, DT, RF and XGBoost), sensitivity (NB and k-NN), and specificity (all except for NB), while the lowest mean misclassification error values were shown by k-NN, DT, RF, and XGBoost. Consequently, the excreted mass of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA can be used to discriminate the volunteers from the DON and control groups. On the contrary, LDA, PLS-DA, and SVM had no sensitivity and NB low specificity (45%) and accuracy (53%). The trade-off comparing the different performance metrics indicated k-NN, DT, XGBoost, and RF methods performed the best since their accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity values were the highest and mean misclassification error the lowest. Therefore, these models were investigated more deeply by fine tuning the specific hyperparameters using a train and test set.

Tuning of k-NN, DT, XGBoost, and RF models was performed by making a grid search of several hyperparameters. For the RF model, ntree (i.e., the number of trees in the forest, from 10 to 500), mtry (i.e., the number of variables randomly sampled at each node, from 1 to 4), nodesize (i.e., the minimum number of instances allowed in a leaf, from 1 to 5), maxnodes (i.e., the maximum number of leaves permitted, from 5 to 20) were evaluated. The optimal k (i.e., the number of nearest neighbors to each instance, from 1 to 15) was determined for k-NN model. For DT, minsplit (i.e., the minimum number of observations a node must have before attempting to split, from 2 to 5) and minbucket (i.e., the minimum number of observations that each terminal node should have after a split, from 1 to 100) hyperparameters were evaluated. Finally, optimal values for min_child_weight (i.e., the minimum sum of instance weights needed in a child node to split, from 1 to 500), gamma (i.e., the minimum loss reduction required for making a split, from 0 to 1), eta (i.e., the scale factor for the contribution of each tree in the boosting process, from 1 to 500), and max_depth (i.e., the maximum depth of each tree, from 1 to 500) were determined for the XGBoost model.

The optimal hyperparameters were selected based on the highest values of accuracy. To optimize them, data were divided into training (67% of the available samples) and test sets (33% of the available samples). The performance of the models built on the training set were assessed by predicting the classification outcomes on the data of the test set. Finally, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Area Under the Curve (AUC) values were computed. The tuned models (ntree = 10, mtry = 1, nodesize = 1, and maxnodes = 5 for RF; k = 6 for k-NN; minsplit = 4 and minbucket = 12 for DT; min_child_weight = 1, gamma = 0, eta = 0.44, and max_depth = 500 for XGBoost) showed optimal performances obtaining AUC values between 0.8988 and 0.9688 and as it can be seen from the ROC curves in Figure 4A. RF, DT, and XGBoost models also allowed to show the importance of the variables as reported in Figure 4B for RF. The highest importance is provided by DON-15-GlcA, followed by DON-3-GlcA and DON for all three model. Therefore, the ML approach confirmed the role of DON-15-GlcA in discriminating DON volunteers group from control individuals as the major validated human urinary biomarker18,19.

The regression plots for the DON dose obtained from the regression benchmark are reported in Figure 5. When comparing predicted vs. measured results, the regression models showed a correlation between the DON, DON-3-GlcA, DON-15-GlcA values and the DON dose. However, the only model for which the R2 resulted acceptable was the RF regression model that achieved R2 = 0.72. Additionally, the aggregated RMSE obtained over the 10 iteration was 60.63, due to the high variability of the collected data, especially from the volunteers of the control group. Finally, no further tuning of the RF regression model was deemed applicable at this stage, as the number of monitored individuals remains relatively low.

Regression plots showing the effective versus predicted dose for several ML regression models. The blue line represents the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression line whose equation is reported in the upper part of each plot, together with the R2 determination coefficient. The models tested were Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forests (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Partial Least Squares-Regression (PLS-R), Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR), Principal Components Regression (PCR), Artificial Neuronal Network (ANN).

In conclusion, the tuned ML classification and regression models provided consistent results and confirmed the findings of Vidal et al. (2018)18. The classification model, specifically RF and k-NN, proved to be effective in differentiating DON from control volunteers. On the contrary, the regression models showed poor prediction of the intake of DON in function of the dose of DON. Additionally, the models were characterized by high values of RMSE due to the high variability of the data and the low sample size. Indeed, a higher number of volunteers should be considered in future studies to validate the findings in the future since the number of instances (n = 20 volunteers) was low for regression studies and uneven for classification purposes (4 control volunteers versus 16 DON volunteers).

Toxicokinetic modelling

The dataset containing DON data were used to verify the application of a Bayesian TK modelling approach by Lu et al. (2023)79, having identified DON, DON-3-GlcA, and DON-15-GlcA as important biomarkers90. The model of Mengelers et al. (2019)19 was modified as shown in Figure 6A, and a hierarchical Bayesian approach was employed to fit the model parameters as well as their inter-individual variability (details reported separately)91. Figure 6B shows the model fits to the urinary excretion data for all three biomarkers, along with 95% Credible Intervals, showing that the model results in excellent fits to the available data, and accounts for inter-individual variability in absorption, metabolism, and excretion. The resulting TK parameter estimates are useful for a variety of applications, including dose reconstruction from human biomonitoring data, derivation of more accurate tolerable daily intakes, and overall risk characterization92,93,94.

A: DON toxicokinetic model based on biomarker identification. The oral dose first enters the GI tract, where it is either eliminated to faeces (at a rate kgutelim) or absorbed systemically (at a rate kgutabs) to the central compartment. The blood concentration is determined by the volume of distribution (Vd) of the central compartment. Elimination is either to unchanged DON in urine (with rate kuD), metabolism to DON-3-GlcA that is excreted in urine (at a rate km_d3g) or metabolism to DON-15-GlcA that is excreted in urine (at a rate km_d15g). Potential biomarkers include the concentration of DON in blood and the amount of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and/or DON-15-GlcA in urine. B: Comparison of model predictions with data after Bayesian population calibration, based on biomarkers of DON, DON-3-GlcA, and/or DON-15-GlcA in urine. In each sub-panel, the symbols represent the data for one of 16 individuals from Vidal et al. (2018), and the lines represent posterior predictions (solid=median prediction; dashed=95% credible interval). Almost all data are within the 95% credible interval, showing adequate model fit. Additionally, substantial inter-individual variability is evident for each biomarker, showing the necessity of a population-based model incorporating random effects for each parameter shown in A. Adapted from Lu et al. (2023)79.

Advantages and limitations

Human intervention trial

The trial was developed to provide TK data on mycotoxins and investigate the presence of unknown biomarkers in humans. By examining the metabolic behaviour of mycotoxins directly in humans, uncertainties linked to the extrapolation of in vitro models, as well as interspecies differences related to animal models can be avoided. Although in vitro and in silico models provide a simplified approach to study the ADME properties of mycotoxins, they cannot encompass the total complexity of an organism95,96,97. Indeed, in vivo experiments on animals are a more comprehensive way to study the behaviour of a xenobiotic, but it is well known that different species have different major metabolic pathways that may lead to a wide variety of TK parameters and metabolites97.

Understanding the potential health consequences in humans necessitates the capability of conducting accurate mycotoxin exposure assessments at the individual level and determining population toxicokinetics. In response to this growing need for accurate mycotoxin exposure assessment, HBM has been evolving, with a shift towards methodologies that are less invasive and more patient-friendly. This transition is pivotal for enhancing our capacity to monitor exposure to mycotoxins in a manner that is both efficient and acceptable to the public. Capillary blood microsampling, particularly using VAMS, allows home and remote sampling by providing a minimally invasive alternative to the traditional blood withdrawal98,99. Microsampling significantly enhances the feasibility of large-scale HBM studies100 and facilitates more comprehensive pharmaco-/toxicokinetic trials101 by increasing patient participation and enabling more frequent sample collection. Moreover, thanks to the improvements of the analytical performances in detection and quantification of analytes, the analysis of capillary blood on VAMS, whole blood, serum, and plasma, provides comparable results in terms of sensitivity101,102. These factors make whole blood microsampling a valid alternative compared to traditional hematic matrices aligning with current trends in analytical methodology that prioritize patient comfort and study feasibility while maintaining analytical rigor103. On the other hand, whole blood is a complex matrix and VAMS can collect only up to 30 µL mining the sensitivity of the quantification method. Therefore, collection of plasma samples, possibly with the aid of a cannula104 to avoid multiple peripheral venipuncture procedures, should be considered in cases in which the performance of the analytical method can represent an important limitation. The sampling strategy for urine and faeces is standard and ubiquitously accepted by the scientific community for the biomonitoring of mycotoxins18,19,105,106,107,108,109,110, although the long sample collection timeframe (48 hours) may be considered a burden in some contexts. Nevertheless, a limitation for this design is connected to the faeces sampling. In fact, for this matrix, no weight is recorded at collection making it impossible to calculate the mass excreted via the GI tract. For mycotoxins excreted predominantly via the GI tract, this limitation must be overcome by recording the mass to obtain a comprehensive description of the excretion profile.

Chemometric filtering and suspect screening

The main limitations of the chemometric filtering approach are represented by the low sample size, which limits the generalizability of the findings and the statistical power of the analyses. TK trials inherently pose certain limitations on sample size when it relates to human subjects, often imposing a smaller sample size due to ethical, logistical, and practical constraints. In this study example, the set was kept as general as possible, including healthy subjects of both gender and from 20 to 65 years old. In other comparative studies investigating biomarkers of exposure111, the general nutrition of all participants is regulated during food consumption studies to minimize the differences that might be attributed to different nutritional habits. However, due to the necessity of collecting samples for up to 48 hours, a less invasive and consuming asset that could be performed at home was prioritized, which is a considerable advantage. Studies recommend a minimum sample size of 200 cases112. PLS-DA, on the other hand, is applicable to very small sample sizes. In fact, a Monte Carlo simulation conducted by Chin et al. (1999)113 showed that PLS-DA can be performed with a sample size as small as 50, and Wold et al. (1975)114 even analysed 27 variables using two latent constructs with a data set consisting of ten cases. Metabolomics datasets are usually characterized by large volume, large number of features, noise, and, eventually, missing data, due to the nature of the metabolomics spectral signals. In the case of highly dimensional data, PLS-DA strives to discern the variation correlated with the clinical outcome by building overly complex models115,116. Therefore, in this study, OPLS-DA was chosen over the classic PLS-DA to disentangle group-predictive and group-unrelated variations in the measured data117. OPLS-DA was applied, through the ropls package58, since it was specifically developed for metabolic data characterized by multi-collinearity among variables. Another aspect to consider is that in source fragmentation and adducts occurring during the ionization of the analyte of interest or isotopes can mimic the presence of metabolites due to the same mass-to-charge ratio detected during suspect screening. For this reason, it is crucial to compare the retention time of any candidate metabolite to that of the original analyte. If the retention time coincides, the candidate probably represents a different ionization state of the same analyte.

Data classification and regression

In terms of ML modelling, a main issue related to human intervention trials involves insufficient participants. A limited number of instances does not allow proper validation of the developed models, neither does it allow a detailed tuning and features selection of the models themselves. As an example, a limited amount of subjects may not allow the use of robust validation strategies such as Repeated Double Cross-Validation, i.e., a strategy to optimize the complexity of supervised models that provides feasible evaluations of the prediction error when the model is applied to new cases. As a rule of thumb, the minimum number of samples of each class for a classification model should be three times the number of the variables, e.g. for 5 variables and 2 classes, the number of samples should be at least 30 (5 variables x 3 x 2 classes). Moreover, small sample sizes influence overfitting. Computing ML models involves, briefly, two steps: first, a particular model form and cost function must be selected, and second, the model must be fitted to external data. The first of these steps is often done by splitting the data into training and test/evaluation data: once a set of candidate models is trained on a subset of the available data, then the validation of the models’ performance is made on the hold-out test set. The model that performs best on the latter is then, traditionally, selected for further studies/implementation. However, the optimal model depends sensitively on the size of the training set. This observation suggests that the paradigm of splitting training and testing should sometimes be taken with caution: since a subsample is used for training in the first selection step, the model identified as optimal may not be the best one when trained with the entire dataset. For this reason, hyperparameter tuning and feature selection strategies can be performed when the sample size is significantly large, so that robust validation and cross-validation strategies can be implemented to avoid overfitting.

Toxicokinetic modelling

There are two main advantages of using Bayesian TK modelling. First, the Bayesian approach allows to incorporate “prior” information based on previous studies and literature. For instance, if there are experimental animal or in vitro data on metabolism, then extrapolation approaches can be used to estimate the rate of metabolism kmet, as was done by Fæste et al. (2018)81 for DON. Those estimates can be used as “central” estimates for the prior probability distribution in the model (Figure 2, panel B, bottom box). Additionally, Bayesian population approaches incorporate random effects across individuals that statistically separate inter-individual variability from measurement error and intra-individual variability118. The advent of MCMC algorithms, the wide availability of powerful computing platforms, and the presence of open-source/free software platforms for conducting these analyses enable the application of these approaches routinely. The main limitations of the approach are that sometimes convergence can be difficult to achieve, requiring re-parameterization or implementation of alternative MCMC algorithms. Additionally, unlike commercial TK software packages such as NONMEM, there is no “user-friendly” graphical interface, and thus some familiarity with command line interfaces is needed to implement the approaches. However, a GitHub repository containing the templates for such implementation was shared within this work, and hence it is hoped to enable a more widespread application.

Conclusions

The design of a human mycotoxin intervention trial was proposed for the investigation of TK and metabolism of IARC-group III mycotoxins. Samples gathered during such a trial and analysed with different analytical technique provides experimental data rich in information79,119,120,121. Different pipelines can be applied on the experimental data, as the data can be elaborated for three different objectives:

-

1)

Identification of metabolites and biomarkers of exposure

-

2)

Determination and validation of the best biomarker for human biomonitoring

-

3)

TK modelling and determination of population TK parameters

The detailed procedure for the data elaboration of each objective is implemented in R and all codes and files required are provided in distinct GitHub repositories.

- 1)

- 2)

- 3)

The standardization of this innovative and holistic framework provides repeatability and reproducibility of experimental results obtained. The gain for the scientific community and risk assessors is high as the TK properties and newly discovered biomarkers will allow public health authorities to perform a comprehensive risk assessment based on biomonitoring rather than food consumption and occurrence data. Eventually, the unique opportunity to provide specific legislation or recommendations regarding the safety of foods for human consumption is offered.

Data availability

All data and detailed R codes for data elaboration are made publicly accessible within the article, its supplementary information, and three dedicated GitHub repositories: 1. https://github.com/liavisintin/OPLSDA_TeA; 2. https://github.com/eugenioalladio/human-mycotoxin-UGent; 3. https://github.com/wachiuphd/Mycotoxin-PK-model.

References

Kamala, A. et al. Outbreak of an acute aflatoxicosis in Tanzania during 2016. World Mycotoxin J. 11, 311–320 (2018).

Pitt, J. I. & Miller, J. D. A concise history of mycotoxin research. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 65, 7021–7033 (2017).

Eskola, M. et al. Worldwide contamination of food-crops with mycotoxins: validity of the widely cited ‘FAO estimate’ of 25%. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 60, 2773–2789 (2020).

De Boevre, M. et al. Human exposure to mycotoxins and their masked forms through cereal-based foods in Belgium. Toxicol. Lett. 218, 281–292 (2013).

World Health Organization & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Consultations and workshops : dietary exposure assessment of chemicals in food : report of a joint FAO/WHO consultation, Annapolis, Maryland, USA, 2-6 May 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44027. 2008

Riley, R., Hambridge, T., Alexander, J., Boon, P., Doerge, D., Edwards, S., Miller, J., Shephard, G., and Zhang, Y. Co-exposure of fumonisins with aflatoxins. safety evaluation of certain contaminants in food: prepared by the eighty-third meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) (2018).

Ueno, Y. & Hsieh, D. P. H. The toxicology of Mycotoxins. CRC Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 14, 99–132 (1985).

Trucksess, M. Mycotoxins. J. AOAC Int. 77, 135–142 (1994).

Peraica, M., Radić, B., Lucić, A. & Pavlović, M. Toxic effects of mycotoxins in humans. Bull. World Health Organ. 77, 754–66 (1999).

Battilani, P. et al. Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change. Sci. Rep. 6, 24328 (2016).

Medina, A., Rodriguez, A. & Magan, N. Effect of climate change on Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin B1 production. Front. Microbiol. 5, 348 (2014).

Matilde Marques, M. et al. Advisory Group recommendations on priorities for the IARC Monographs. Lancet Oncol. 20, 763–764 (2019).

Berrington de González, A. et al. Advisory group recommendations on priorities for the IARC monographs. Lancet Oncol. 25, 546–548 (2024).

Atkinson, A. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 69, 89–95 (2001).

Vidal, A., Mengelers, M., Yang, S., De Saeger, S. & De Boevre, M. Mycotoxin biomarkers of exposure: a comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 17, 1127–1155 (2018).

van der Westhuizen, L., Shephard, G. S., Gelderblom, W. C. A., Torres, O. & Riley, R. T. Fumonisin biomarkers in maize eaters and implications for human disease. World Mycotoxin J. 6, 223–232 (2013).

van der Westhuizen, L., Brown, N. L., Marasas, W. F. O., Swanevelder, S. & Shephard, G. S. Sphinganine/Sphingosine ratio in plasma and urine as a possible biomarker for fumonisin exposure in humans in rural areas of Africa. Food Chem. Toxicol. 37, 1153–1158 (1999).

Vidal, A. et al. Humans significantly metabolize and excrete the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol and its modified form deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside within 24 hours. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Mengelers, M. et al. Biomonitoring of deoxynivalenol and deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside in human volunteers: renal excretion profiles. Toxins (Basel) 11, 466 (2019).

McMillan, A. et al. Aflatoxin exposure in Nigerian children with severe acute malnutrition. Food Chem. Toxicol. 111, 356–362 (2018).

Leardi, R., Seasholtz, M. B. & Pell, R. J. Variable selection for multivariate calibration using a genetic algorithm: prediction of additive concentrations in polymer films from Fourier transform-infrared spectral data. Anal. Chim. Acta 461, 189–200 (2002).

Jouan-Rimbaud, D., Massart, D.-L., Leardi, R. & De Noord, O. E. Genetic algorithms as a tool for wavelength selection in multivariate calibration. Anal. Chem. 67, 4295–4301 (1995).

Kowalski, B. R. & Seasholtz, M. B. Recent developments in multivariate calibration. J. Chemom. 5, 129–145 (1991).

Kumar, N., Bansal, A., Sarma, G. S. & Rawal, R. K. Chemometrics tools used in analytical chemistry: an overview. Talanta 123, 186–199 (2014).

Geladi, P. Analysis of multi-way (multi-mode) data. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 7, 11–30 (1989).

Massart, D. L. et al. Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics: Part A (The Netherlands, 1997).

Bro, R. & Smilde, A. K. Principal component analysis. Anal. Methods 6, 2812–2831 (2014).

Wold, S. & Sjostrom, M. SIMCA: A method for analysing chemical data in terms of similarity and analogy. In B. R. Kowalski (Ed.), Chemometrics, theory and application. ACS symposium series 52 243 (1977)

Ballabio, D. & Consonni, V. Classification tools in chemistry. Part 1: linear models. PLS-DA. Anal. Methods 5, 3790–3798 (2013).

Beygelzimer, A. et al. FNN: fast nearest neighbor search algorithms and applications. Preprint at (2019).

Truong, N. N. et al. Associating multiple mycotoxin exposure and health outcomes: current statistical approaches and challenges. World Mycotoxin J. 16, 25 (2022).

Ulenberg, S., Belka, M. & Bączek, T. Comparison of MLR, OPLS, and SVM as potent chemometric techniques used to estimate in vitro metabolic stability. J. Chemom. 30, 177–181 (2016).

Wentzell, P. D. & Vega Montoto, L. Comparison of principal components regression and partial least squares regression through generic simulations of complex mixtures. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 65, 257–279 (2003).

Grenier, B. & Applegate, T. J. Modulation of intestinal functions following mycotoxin ingestion: meta-analysis of published experiments in animals. 396–430 https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins5020396. (2013)

Antonissen, G. et al. The impact of fusarium mycotoxins on human and animal host susceptibility to infectious diseases. Toxins (Basel) 6, 430–452 (2014).

Pierron, A., Alassane-kpembi, I. & Oswald, I. P. Impact of two mycotoxins deoxynivalenol and fumonisin on pig intestinal health. Porcine Health Manag. 2, 1–8 (2016).

Wedagedera, J. R. et al. Population PBPK modelling using parametric and nonparametric methods of the simcyp® simulator, and bayesian samplers. Pharmacomet. & Syst. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1002/PSP4.12787 (2022).

Hsieh, N.-H. et al. A Bayesian population physiologically based pharmacokinetic absorption modeling approach to support generic drug development: application to bupropion hydrochloride oral dosage forms. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-021-09778-5 (2021).

Dalaijamts, C., Cichocki, J. A., Luo, Y.-S., Rusyn, I. & Chiu, W. A. Quantitative characterization of population-wide tissue-and metabolite-specific variability in perchloroethylene toxicokinetics in male mice. Toxicol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.brv15dv94 (2021).

Chiu, W. A., Okino, M. S. & Evans, M. V. Characterizing uncertainty and population variability in the toxicokinetics of trichloroethylene and metabolites in mice, rats, and humans using an updated database, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model, and Bayesian approach. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 241, 36–60 (2009).

De Paepe, E. et al. A validated multi-matrix platform for metabolomic fingerprinting of human urine, feces and plasma using ultra-high performance liquid-chromatography coupled to hybrid orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim Acta 1033, 108–118 (2018).

Braun, D. et al. Monitoring Early Life Mycotoxin Exposures via LC-MS/MS Breast Milk Analysis. Anal Chem 90, 14569–14577 (2018).

Kyei, N. N. A., Boakye, D. & Gabrysch, S. Maternal mycotoxin exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Mycotoxin Res. 36, 243–255 (2020).

Nielsen, J. K. S., Vikström, A. C., Turner, P. & Knudsen, L. E. Deoxynivalenol transport across the human placental barrier. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49, 2046–2052 (2011).

Warth, B. et al. Transfer and metabolism of the xenoestrogen zearalenone in human perfused placenta. Environ. Health Perspect. 127, 107004 (2019).

Martins, C. et al. earlyMYCO: a pilot mother-child cohort study to assess early-life exposure to mycotoxins—challenges and lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 7716 (2022).

More, S. J. et al. Guidance on the use of the Threshold of Toxicological Concern approach in food safety assessment. EFSA Journal 17 (2019).

De Spiegeleer, M. et al. Impact of storage conditions on the human stool metabolome and lipidome: preserving the most accurate fingerprint. Anal. Chim Acta 1108, 79–88 (2020).

Visintin, L. et al. Unraveling biomarkers of exposure for tenuazonic acid through urinary metabolomics. Food Chem. Toxicol. 182, 114183 (2023).

Audano, M. et al. Investigating metabolism by mass spectrometry: from steady state to dynamic view. J. Mass Spectrom. 56, 1–12 (2021).

Arroyo-Manzanares, N., Campillo, N., López-García, I., Hernández-Córdoba, M. & Viñas, P. High-resolution mass spectrometry for the determination of mycotoxins in biological samples. Rev. Microchem. J. 166, 106197 (2021).

Malachová, A. et al. Advanced LC–MS-based methods to study the co-occurrence and metabolization of multiple mycotoxins in cereals and cereal-based food. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 410, 801–825 (2018).

Alladio, E. et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on alcohol consumption: a perspective from hair analysis. Front. Psychiatr. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Chen, L., Zhong, F. & Zhu, J. Bridging targeted and untargeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics via hybrid approaches. Metabolites 10, 1–19 (2020).

Compound discoverer. https://www.thermofisher.com/be/en/home/industrial/mass-spectrometry/liquid-chromatography-mass-spectrometry-lc-ms/lc-ms-software/multi-omics-data-analysis/compound-discoverer-software.html?erpType=Global_E1#menu1 (2025).

R Core Team, R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2022).

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Preprint at (2020).

Thévenot, E. A., Roux, A., Xu, Y., Ezan, E. & Junot, C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index, and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J. Proteome Res. 14, 3322–3335 (2015).

R Core Team, R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2022).

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Preprint at (2020).

Bhattacharjee, M., Dhar, S. K. & Subramanian, S. Recent advances in biostatistics. (World Scientific). https://doi.org/10.1142/8010. (2011)

Hubert, M., Rousseeuw, P. J. & Vanden Branden, K. ROBPCA: A new approach to robust principal component analysis. Technometrics 47, 64–79 (2005).

Mazzara, S. Application of multivariate data analysis for the classification of two dimensional gel images in neuroproteomics. J. Proteom. Bioinform. 04, 16–21 (2011).

de Bruyn Kops, C. et al. GLORY: generator of the structures of likely cytochrome P450 metabolites based on predicted sites of metabolism. Front. Chem. 7, 1–15 (2019).

de Bruyn Kops, C., Šícho, M., Mazzolari, A. & Kirchmair, J. GLORYx: prediction of the metabolites resulting from phase 1 and phase 2 biotransformations of xenobiotics. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 34, 286–299 (2021).

Progenesis QI software. https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/products/informatics-and-software/mass-spectrometry-software/progenesis-qi-software.html (2025).

Meyer, D. et al. Package ‘e1071’ - Misc functions of the department of statistics probability theory group (Formerly: E1071) TU Wien (2019).

Vapnik, V. N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. (1995).

Therneau, T. & Atkinson, B. rpart: Recursive partitioning and regression trees. Preprint at (2019).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R. News 2, 18–22 (2002).

Chen, T. et al. xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. Preprint at (2021).

Probst, P., Au, Q., Casalicchio, G., Stachl, C. & Bischl, B. Multilabel classification with R Package mlr (2017).

Nascimento, R. S. et al. Comparison between ordinary least squares regression and weighted least squares regression in the calibration of metals present in human milk determined by ICP-OES. Talanta 80, 1102–1109 (2010).

Vigneau, E., Bertrand, D. & Qannari, E. M. Application of latent root regression for calibration in near-infrared spectroscopy. Comparison with principal component regression and partial least squares. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 35, 231–238 (1996).

Mevik, B.-H., Wehrens, R. & Liland, K. H. pls: Partial least squares and principal component regression. Preprint at (2020).

Fritsch, S., Guenther, F. & Wright, M. N. neuralnet: training of neural networks. Preprint at (2019).

LeDell, E. et al. h2o: R Interface for the ‘H2O’ scalable machine learning platform. Preprint at (2021).

Bischl, B. et al. {mlr}: machine learning in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–5 (2016).

Lu, E. H. et al. Advancing probabilistic risk assessment by integrating human biomonitoring, new approach methods, and Bayesian modeling: A case study with the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Environ. Int. 182, 108326 (2023).

Gelman, A., Bois, F. & Jiang, J. Physiological pharmacokinetic analysis using population modeling and informative prior distributions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 1400–1412 (1996).

Fæste, C. K. et al. Prediction of deoxynivalenol toxicokinetics in humans by in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation and allometric scaling of in vivo animal data. Arch. Toxicol. 92, 2195–2216 (2018).

Andrieu, C., De Freitas, N., Doucet, A. & Jordan, M. I. An introduction to MCMC for machine learning. Mach. Learn. 50, 5–43 (2003).

Krauss, M. et al. Using Bayesian-PBPK modeling for assessment of inter-individual variability and subgroup stratification. Silico. Pharmacol. 1, 6 (2013).

van Ravenzwaaij, D., Cassey, P. & Brown, S. D. A simple introduction to Markov Chain Monte-Carlo sampling. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 143–154 (2018).

Bois, F. Y. GNU MCSim: Bayesian statistical inference for SBML-coded systems biology models. Bioinformatics 25 1453–1454 https://www.gnu.org/software/mcsim/ (2009)

Geman, S. & Geman, D. Stochastic relaxation, gibbs distributions, and the bayesian restoration of images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.1984.4767596 (1984).

Gelfand, A. E. & Smith, A. F. M. Sampling-based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 85, 398–409 (1990).

Gelman, A. & Rubin, D. B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. sci. https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/11770111367.457-472 (1992).

Gelman, A. & Meng, X. L. Applied Bayesian Modeling and Causal Inference from Incomplete-Data Perspectives (John Wiley & Sons Inc Chichester, 2004).

Lu, E. H. et al. Advancing probabilistic risk assessment by integrating human biomonitoring, new approach methods, and Bayesian modeling: a case study with the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Environ. Int. 182, 108326 (2023).

Gelman, A., Bois, F. & Jiang, J. Physiological pharmacokinetic analysis using population modeling and informative prior distributions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 1400–1412 (1996).

Tohon, H., Nong, A., Moreau, M., Valcke, M. & Haddad, S. Reverse dosimetry modeling of toluene exposure concentrations based on biomonitoring levels from the Canadian health measures survey. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health - Part A: Curr. Issues 81, 1066–1082 (2018).

Brown, K. et al. Reconstructing exposures from biomarkers using exposure-pharmacokinetic modeling–a case study with carbaryl. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 73, 689–698 (2015).

U.S. EPA. Approaches for the application of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and supporting data in risk assessment (Final Report). (2006).

Johanson, G. Toxicokinetics and modeling. Comprehensive Toxicology 14 (Elsevier 2018).

Fæste, C. K. et al. Prediction of deoxynivalenol toxicokinetics in humans by in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation and allometric scaling of in vivo animal data. Arch. Toxicol. 92, 2195–2216 (2018).

Coecke, S. et al. Toxicokinetics as a key to the integrated toxicity risk assessment based primarily on non-animal approaches. Toxicol. In Vitro 27, 1570–1577 (2013).

Stove, C. P., Ingels, A.-S.M.E., De Kesel, P. M. M. & Lambert, W. E. Dried blood spots in toxicology: from the cradle to the grave?. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 42, 230–243 (2012).

De Kesel, P. M. M., Lambert, W. E. & Stove, C. P. Does volumetric absorptive microsampling eliminate the hematocrit bias for caffeine and paraxanthine in dried blood samples?. Comp. study. Anal. Chim Acta 881, 65–73 (2015).

Bastos-Moreira, Y. et al. A multi-omics and human biomonitoring approach to assessing the effectiveness of fortified balanced energy-protein supplementation on maternal and newborn health in burkina faso: a study protocol. Nutrients 15, 4056 (2023).

Delahaye, L., Baerdemaeker, L. . De. & Stove, C. P. Determination of paracetamol and its metabolites via LC-MS/MS in dried blood volumetric absorptive microsamples: a tool for pharmacokinetic studies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 206, 114361 (2021).

Vidal, A. et al. Volumetric absorptive microsampling as an alternative tool for biomonitoring of multi-mycotoxin exposure in resource-limited areas. Toxins (Basel) 13, 1–21 (2021).

Lei, B. U. W. & Prow, T. W. A review of microsampling techniques and their social impact. Biomed. Microdevices 21, 4 (2019).

Guerra Valero, Y. et al. Microsampling to support pharmacokinetic clinical studies in pediatrics. Pediatr. Res. 91, 1557–1561 (2022).

Deng, Y. et al. Biomarkers of deoxynivalenol (DON) and its modified form DON-3-glucoside (DON-3G) in humans. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 110, 551–558 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Development of a sensitive and reliable UHPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of multiple urinary biomarkers of mycotoxin exposure. Toxins (Basel) 12, 1–19 (2020).

Abia, W. A. et al. Bio-monitoring of mycotoxin exposure in cameroon using a urinary multi-biomarker approach. Food Chem. Toxicol. 62, 927–934 (2013).

Martins, C. et al. Exposure assessment of Portuguese population to multiple mycotoxins: the human biomonitoring approach. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 222, 913–925 (2019).

Krausová, M. et al. Trace analysis of emerging and regulated mycotoxins in infant stool by LC-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 414, 7503–7516 (2022).

Turner, P. C. et al. Dietary wheat reduction decreases the level of urinary deoxynivalenol in UK adults. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 18, 392–399 (2008).

Maruvada, P. et al. Perspective: dietary biomarkers of intake and exposure - exploration with omics approaches. Adv. Nutr. 11, 200–215 (2020).

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., Balla, J. R. & Grayson, D. Is more ever too much? the number of indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 33, 181–220 (1998).

Chin, W. W. & Newsted, P. R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. in (1999).

Wold, H. Soft modelling by latent variables: the non-linear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) approach. J. Appl. Probab. 12, 117–142 (1975).

Bylesjö, M. et al. OPLS discriminant analysis: combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. J. Chemom. 20, 341–351 (2006).

Trygg, J. & Wold, S. Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J. Chemom. 16, 119–128 (2002).

Worley, B. & Powers, R. PCA as a practical indicator of OPLS-DA model reliability. Curr. Metabol. 4, 97–103 (2016).

Bois, F. Y., Jamei, M. & Clewell, H. J. PBPK modelling of inter-individual variability in the pharmacokinetics of environmental chemicals. Toxicology 278, 256–267 (2010).

Visintin, L. et al. Derivation of human toxicokinetic parameters and internal threshold of toxicological concern for tenuazonic acid through a human intervention trial and hierarchical Bayesian population modeling. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00746-6 (2025).

Vidal, A. et al. Humans significantly metabolize and excrete the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol and its modified form deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside within 24 hours. Sci. Rep. 8, 5255 (2018).

Mengelers, M. et al. Biomonitoring of deoxynivalenol and deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside in human volunteers: Renal excretion profiles. Toxins (Basel) 11, 466 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 946192, HUMYCO). These results reflect only the authors’ view and the ERC is not responsible for any use that be made of the information it contains.

Funding

Horizon Europe European Research Council,946192,946192,946192,U.S. NIH/NIEHS,P30 ES029067,P30 ES029067,P30 ES029067.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.D.B., E.A., and W.C.; Data curation: L.V., E. L. and E.A.; Formal analysis: L.V., E. L., and M.G.N.; Funding acquisition, M.D.B.; Investigation: L.V., E.A. and W.C.; Methodology: M.D.B., E.A., and W.C.; Project administration: M.D.B. and T.G.; Resources: M.D.B. and W.C.; Software: E.A. and W.C.; Supervision: S.D.S., M.D.B., E.A., and W.C.; Writing – original draft, L.V. and M.G.N.; Writing – review & editing, L.V., T.G., S.D.S., M.D.B., E.A., and W.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions