Abstract

Annually, colorectal cancer (CRC) claims nearly 700,000 lives globally, thereby positioning it among the most lethal diseases worldwide. Scutellaria barbata D. Don (BZL), acknowledged for its demonstrated efficacy, is currently undergoing investigation as a potential therapeutic recourse for this formidable cancer. Seven diterpenes were tested, leading to identification of BZL-5 as the most promising compound. It exhibits activity against colorectal cancer via a number of different targets and mechanisms. Its ability to combat oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis is believed to be the mechanism of action. With respect to BZL-5, HIF1A exhibits the highest binding affinity, and HIF-1 may be a crucial component in the pharmacological pathway. Experimental verification in vitro was explored the possible mechanism of BZL against colorectal cancer using a thorough analytical approach. The overarching objectives of this investigation are to demystify the underlying molecular mechanism and identify potential targets instrumental in the development of novel colorectal cancer therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The third most frequent cancer in the world, colorectal cancer (CRC) is becoming more commonplace due to rising incidence and death rates worldwide. Traditionally, patients with colorectal cancer have had surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, often in combination. Unfortunately, because of their cytotoxicity and lack of specificity, these treatments have several adverse effects on all cells, including healthy cells that are proliferating and dividing. Moreover, a lot of people experience relapses even after receiving multiple treatments1. Of all malignancies worldwide, CRC has an incidence of 10.2% and a fatality rate of 9.2%. The incidence and death rate from CRC rose by about 20% in developing nations including China, Brazil, and Argentina. Moreover, the prognosis for individuals with metastatic CRC is still dismal, with a median 5-year survival of just 18.5% in the US and 27.7% in Europe2. In treating CRC, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) offers a wealth of experience and special benefits. By using in vitro/in vivo validation studies and network pharmacology, we were able to determine that the ferritinophagy pathway is how Banxia Xiexin decoction (BXD) carries out its anti-CRC actions. Additionally, we clarified the possible mechanism by which it induces ferritinophagy. These results support the broader clinical application of standard medications in combination with chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, and show their considerable promise in controlling colorectal cancer3. Systems biology and network informatics are combined to create the broad field of network pharmacology. It has recently been extensively employed in the development of novel drugs. Systems biology holds that numerous gene mutations that upset the balance of the biological network system are what generate complex diseases like cancer, rather than a single target gene mutation. The goal of network pharmacology is to investigate how biological networks are balanced. It can be used to examine how multi-component medications affect the body at the systemic level, which aids in identifying therapeutic targets for the active compounds in the medications, enhancing their effectiveness, and minimizing their adverse effects4. Molecular docking is a computer simulation technique that can predict the conformation of ligands and receptors, simulate atomic-level interactions between chemicals and proteins, and compute certain characteristics, such affinity, that are used to assess combination cases. Currently, the method is mostly utilized for drug design and biochemical pathway elucidation because of its accuracy and inexpensive cost5. In the field of biomedicine, molecular dynamics modeling is frequently utilized to examine how ligand binding and unbinding or mutations in proteins cause conformational changes in proteins. It offers various viewpoints that are challenging to find in conventional biochemical or pathological tests, such as the in-depth impact of mutations on the structure of proteins and the atomic-level interactions between proteins and ligands6.

Utilizing network pharmacology methodologies enhances our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of TCM and their formulations in treating CRC, aiding subsequent validation efforts. For instance, the key bioactive compounds of Xianlian Jiedu decoction (XJD) were identified and curated from databases to determine the overlap between compound-specific targets and disease-related targets. Experimental validation using CRC cell and xenograft models in nude mice confirmed that XJD exerts its therapeutic effects on CRC by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway7. A comprehensive approach encompassing MTT assay, network pharmacology analysis, bioinformatics, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation was employed to investigate the bioactive constituents, targets, and potential mechanisms of Ardisia gigantifolia Stapf. (AGS) against CRC. The findings underscored the significant pharmacological role of polyphenolic compounds within AGS. Notably, key targets were postulated to include SRC, MAPK1, ESR1, HSP90AA1, and MAPK8, with the MAPK signaling pathway identified as central, a finding corroborated by both in vitro and in vivo experiments8. Thus, the widespread utilization of methodologies such as network pharmacology enables the efficient and prompt prediction of the active constituents and mechanisms of action of traditional Chinese medicines.

Scutellaria barbata D. Don (BZL), also called “Ban Zhi Lian” in Chinese, is a plant with a long historical background entwined with traditional medicine. For millennia, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has used this perennial plant, which is highly valued for its numerous medicinal benefits. Its usage in treating a variety of illnesses, such as fevers, infections, and inflammations, is documented in historical writings, highlighting its importance in traditional medical procedures9. Geographically, the temperate parts of East Asia, especially China, are home to BZL, which grows wild there. The plant is usually gathered in late summer or early fall when its active ingredients are at their highest concentrations. It grows best in moist, well-drained soils. BZL is composed of many different substances, including alkaloids, terpenoids, and flavonoids. These substances are known to have strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects10. Research has elucidated the mechanisms through which these flavonoids exert their effects, including the modulation of signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Compared to other TCM herbs, BZL diterpenoids have demonstrated superior typically inhibit tumor growth by improving the inflammatory microenvironment associated with tumor growth. By disrupting angiogenesis, diterpenoids can effectively deprive tumors of nutrients and oxygen11. To put it succinctly, diterpenes’ anti-tumor qualities exhibit a variety of impacts on several facets of tumor biology, indicating their potential as therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. To fully comprehend the mechanisms and maximize their application in clinical settings, more research is required. Because of these pharmacological qualities, they present a promising option for integrated cancer treatment12.

This study employs network pharmacology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and experimental verification to investigate the primary objectives of halting medication and aims to identify the active components in BZL that are associated with colorectal cancer.

Methods and materials

Plant material

In this study, the aerial parts of S. barbata were collected in September 2021 from Nantong, Jiangsu Province, China. The plant material was authenticated by Prof. Chen (Department of Pharmacy, Nantong University, Nantong 226001, China). A voucher specimen (No. 2021022) has been deposited in the School of Pharmacy, Nantong University, Nantong, Jiangsu province, China.

Characterization of compounds

Tetramethylsilane was used as an internal standard while measuring the NMR spectra in methanol-d4 using a Bruker AV600 instrument. The JASCO pu-2080 spectrometer was used to measure the circular dichroism spectrum. At 20 ℃, the Peking-Elmer 241 MC Spectropolarimeter was used to quantify optical rotations. HPLC was carried out utilizing a JAI refractive index detector and a JAI UV-3702 detector with MultiChro 2000 workstation on a JAI LC9103 recycling preparative HPLC (Japan Analytical Industries) outfitted with a JAIGEL-ODS-AP-P column (YMC-Pack ODS-AQ 15 μm; 500 × 20 mm [YMC, Japan]; 25 °C). Using precoated GF254 plates (Merck), thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was used to detect the samples. Followed by spraying with 10% sulfuric acid and heating. Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and methanol (MeOH) in a 100:5 ratio were used as the mobile phase for TLC.

Isolation of compounds

To get rid of the dust, 10 kg of dried BZL aerial components were cleaned with distilled water. The herb was then extracted three times (for two hours each) using reflux-friendly 95% EtOH. To obtain the 95% ethanolic extracts, the solvent was evaporated using a vacuum rotary evaporator. After being dissolved in water, the entire extract (460 g) was divided into three parts using petroleum ether (PE), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and n-butanol (n-Bu), in that order. Fractional extracts were obtained by freezing-drying the residue left over after organic solvents were eliminated from the fractional mixtures. The weights of the fractional extracts, PE, EtOAc, n-Bu, and aqueous layer were 10 g, 90 g, 130 g, and 210 g, respectively. Following solvent evaporation, four fractions (Fr.B-1 ~ Fr.B-4) were obtained from the EtOAc fractional extract by silica gel column chromatography (5 cm × 100 cm) and eluted with a gradient of PE-EtOAc (from 100:0 to 0:100, v/v). Fr. B-2 (11 g) was used in a silica gel column chromatography (2 cm × 30 cm) with PE-EtOAc (from 100:0 to 100:10, v/v) as the mobile phase. This resulted in five fractions (Fr. B-2-1 ~ Fr. B-2-5) after the solvent had evaporated. Fr. B-2-1 was purified by preparative HPLC (MeOH-H2O, 80:20, v/v) (JAIGEL-ODS-AP-P column, 250 mm × 20 mm, 4 μm, a flow rate of 5 mL/min) to yield compound 1 (2.5 mg), 3 (5.2 mg), 7 (11.2 mg). Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (1.5 cm × 100 cm) was used to separate Fr. B-2-1. Fr. B-2-3 was purified by preparative HPLC (MeOH-H2O, 75:25, v/v) (JAIGEL-ODS-AP-P column, 250 mm × 20 mm, 4 μm, a flow rate of 5 mL/min) after being separated using Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (1.5 cm × 100 cm) by eluting with MeOH-H2O (75:25, v/v). Compounds 2 (4.2 mg), 4 (6.9 mg), 5 (6.8 mg), 6 (9.3 mg) were obtained.

Common targets prediction of drug and disease

First, we searched the eight terpenoid compounds from the super-PRED database (https://prediction.charite.de/subpages/) to obtain target genes of the compounds. Then, five databases were used to search colorectal cancer-related genes: the OMIM database (https://omim.org/)13, the DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca/)14, the DisGeNet database (https://www.disgenet.org/home/)15, the Genecards database (https://www.genecards.org/)16, and the TTD database (http://db.idrblab.net/ttd/)17. By combining the search results, we created gene set associated with colorectal cancer. Crossing the gene sets for BZL targets and colorectal cancer, a gene set relevant to both conditions was obtained using Venny2.1.0 software.

Construction of the PPI network

For study of protein-protein interactions (PPI), the putative common targets were imported into the STRING database (https://www.string-db.org)18. As an analysis criterion, we established a confidence level of 0.7 to ensure the validity and accuracy of the data. After that, the data was processed in Cytoscape 3.10.2, where edge thickness was determined by the combination score, and the degree value correlated with node size. As a result, a network diagram showing the interactions between common protein targets was made. By applying the median values of Degree, Betweenness Centrality (BC), and Closeness Centrality (CC), we were able to identify important targets of terpenoids compounds against colorectal cancer using node-based topological centrality measurements. The degree of each node denotes the number of direct connections it has; a higher degree indicates greater influence. The interaction networks were visualized using Cytoscape 3.10.2.

KEGG pathway enrichment and GO function analysis of key targets

We imported the acquired key targets into the Sandbox database (golgi.sandbox.google.com). For the KEGG pathway enrichment and GO function analysis of key targets, the species was chosen as human, the minimum overlap value was set to 3, the P value cutoff was set to P < 0.05, and the minimum enrichment value was set to 1.5. The KEGG pathway and GO function were visualized using bubble diagrams. After sorting the gene proportions from large to small, a histogram analysis was performed on the top 10 GO functions19,20,21.

Construction of ‘drug-target-pathway-disease’ network

Using Cytoscape 3.10.2, the “drug-target-pathway-disease” network diagram was created. Only the targets connected to the ten KEGG pathways with the lowest P values were kept; those not connected to these pathways were eliminated in order to clearly show the association between critical targets and pathways.

Molecular docking

To molecularly dock terpenoids, use AutoDock software (https://vina.scripps.edu/). First, Discovery studio was used to view the ligands and water molecules after downloading the protein PDB format file from( https://www.rcsb.org/). Chemdraw 3D was used to open the ligands, process them for energy minimization, and produce a file in MOL2 format. HIF1A receptor docking center coordinates are x = 22.234, y = 26.816, z = 28.218, and docking box size is x = 68.95, y = 68.95. z = 68.95. HSP90AA1 receptor docking’s center coordinates are x = 22.201, y = 26.963, z = 28.304, and the docking box’s dimensions are x = 84.0, y = 84.0, and z = 84.0. The docking box’s dimensions are x = 72.8, y = 72.8, and z = 72.8. The center coordinates for TLR4 docking were x = 22.201, y = 26.963 and z = 28.304. The size of the docking box is x = 119.35, y = 119.35, z = 119.35, and the primary coordinate for receptor docking was NFKB1 as x = 24.671, y = − 0.801, z = − 23.125. A more stable bond between the ligand and receptor is indicated by a larger absolute value of binding free energy in docking. The free energy of interaction between terpenoids and target proteins is expressed as binding affinity (kcal/mol).

Molecular dynamic simulations

For molecular dynamics simulation using the Amber18 software program, the eight terpenoid compounds and target protein exhibiting the highest absolute binding free energy from molecular docking were selected. The protein was subjected to the AMBER 32SB force field characteristics, whilst the small molecule ligands were subjected to the yellow general force field. The OPC water model was used to provide a solvent to the protein-ligand system. Na+/Cl− ions were added to a water box to keep tto maintain the system’s neutrality. A 2500-step conjugate gradient method and a 2500-step steepest descent method were used to optimize the complex system’s energy. After that, the system temperature was gradually increased at constant volume and heating rate, from 0 K to 300 K. At a constant temperature of 300 K, an NVT (isothermal and isovolumic) simulation lasting 200 ps was carried out to distribute solvent molecules uniformly. Ultimately, an NPT (isothermal and isobaric) simulation lasting 250 ns was performed on the combined system. The cutoff distance for nonbonded interactions in the molecular dynamics simulations was set to 10 Å. The CPPTRAJ module was utilized to perform root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis. The MMPBSA.py program was utilized to compute the binding free energy of active chemicals and proteins using the molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) technique. One important metric for evaluating the effectiveness of pharmacological compounds is the binding free energy, with a lower value suggesting a more stable complex.

Cell lines

The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) supplied human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116 and FHC). 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics and antimycotics were added to the media (RPMI 1640, DMEM) in which the cells were cultivated.

Cell viability assay

The cells were incubated in a humidified environment at 37℃ with 5% carbon dioxide. Sulforhodamine B protein staining was used to assess cell viability. Following 24 h of incubation, the cells were either frozen or treated with test drugs for 72 h in 96-well plates. Prior to each experiment, compound was diluted to the appropriate concentration (0, 2, 4, 8, and 16 µM) in normal saline after being solved in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 0.1% [v/v] and kept at -20℃. Three tests were conducted on each concentration. There were at least three experiments conducted. The cells were incubated, fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and stained with 0.4% sulforhodamine B in a solution of 1% acetic acid. After washing the unbound dye and drying the stained cells, they were dissolved in 10 mM Tris (pH 10.0). Cell proliferation was calculated using the following method, with absorbance measured at 515 nm: (Average absorbance compound - average absorbance zero day) / (average absorbancecontrol- average absorbance zero day) × 100% is the formula for cell proliferation (%). The Table Curve 2D program was used to do nonlinear regression analysis and determine the GI50 values.

Colony formation

A colony formation experiment was carried out to evaluate the capacity of the cells. For 10 days, 400 monolayer cells per well were cultivated in 6-well plates. Following a 15-minute methanol fixation, cells were stained with GIMSA for 30 min. After taking images of the colonies, ImageJ software was used to count how many there were. After being planted in 6-well plates, the monolayer cells were cultured in the serum-free media for the entire night.

Transwell assay

After 24 h of starvation, 200 µl of serum-free medium at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml was seeded in a 24-well transwell plate’s upper chamber with 8 μm pore size (Corning, NY, USA). 600 µl of medium supplemented with 10% FBS was placed into the lower chamber. The cells on the membrane’s upper side were removed via cotton swabs after a 24 h incubation period, and the cells on the lower surface were preserved with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The cells, after staining, were subsequently enumerated utilizing light microscope, and pictures of three replicate wells’ worth of randomly chosen fields were taken for assessment.

Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis assay

After serum starvation, HCT-116 cells were plated in a 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 10^5 cells per well and treated with BZL-5 for 48 h. The cells were then taken out and put in a binding buffer. After applying a combination solution of Annexin V-FITC (5 µl) and PI (5 µl) to the 400 µl cell suspension, it was incubated for 15 min in the dark. The samples were examined using flow cytometry, and the FlowJo 7.6 software was used to evaluate the data that was obtained.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Utilizing the Trizol reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology Co., China), total RNA was isolated from cell lines. After using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher, USA) to quantify the total RNA, the kit (Cwbio Century Biotechnology Co., China) was used to reverse-transcribe the RNA into cDNA. A QuantStudio 3 fluorescent quantitative PCR device was then used to amplify the cDNA according to the SYBR kit (Cwbio Century Biotechnology Co., China). The PCR reaction was run at 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 cycles (95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min). GAPDH served as an internal reference gene for the comparative approach (2 − ΔΔCt) utilized to calculate relative mRNA levels. Table 1 shows the primer sequences that were utilized (Huada Gene Research Institute, China).

Statistical analysis

The data were evaluated using the SPSS 22.0 program. The mean plus or minus standard deviation was used to display the data. Group comparisons were made using the Tukey’s post hoc test and one-way ANOVA; a P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

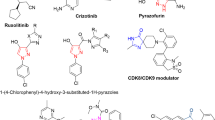

Isolation and identification compounds from BZL

Seven main components were isolated from BZL by various chromatographic methods, and their structures were determined by various spectral methods. They were scutebata D (1) 22, scutebata O (2) 23, scutebata F (3) 22, scutebata G (4) 24, barbatin A (5) 25, scutebarbatine F (6) 25, scutebarbatine G (7) 25 (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Targets genes of main compounds and PPI network analysis

Seven terpenoid compounds were linked to 799 targets in total, which were obtained from the Super-PRED database. 177 distinct targets remained after duplicates were eliminated. Furthermore, 1206 pertinent targets were found in the DisGeNET database, while 5,929 targets associated with colorectal cancer were taken from the GeneCards database. In addition, a total of 6,726 targets relevant to colorectal cancer were retrieved from the TTD database, 502 targets from the OMIM database, and 38 targets from the DrugBank database. Eight terpenoids and colorectal cancer may share 126 potential targets, according to an intersection of these two target categories (Fig. 2A). Specific screening criteria were created based on the centrality measurements of network topology, namely degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality: degree value ≥ 10, BC ≥ 0.003, and CC > 0.400. Thirty-two major targets were found in this study, indicating that these targets are important members of the network and could be potential targets for the seven terpenoids (Fig. 2B). The top ten targets according to CC, BC, degree value, and gene names. The top ten targets based on degree value are STAT3 (Degree = 24, BC = 0.133383, CC = 0.794872), HSP90AA1 (Degree = 21, BC = 0.142569, CC = 0.738095), NFKB1 (Degree = 20, BC = 0.075424, CC = 0.720930), HIF1A (Degree = 20, BC = 0.091745, CC = 0.720930), TLR4 (Degree = 18, BC = 0.086517, CC = 0.688889), PIK3CA (Degree = 17, BC = 0.021210, CC = 0.673913), CXCR4 (Degree = 15, BC = 0.016159, CC = 0.645833), KDR (Degree = 14, BC = 0.008538, CC = 0.620001), TGFBR2 (Degree = 13, BC = 0.009104, CC = 0.620001) and PIK3CG (Degree = 12, BC = 0.026145, CC = 0.620001). Table 3 summarizes the gene names along with their degree values, BC, and CC for these key targets. The interaction network diagram for these targets is illustrated. The top five targets based on degree value are STAT3 (Degree = 24), HSP90AA1 (Degree = 21), HIF1A (Degree = 20), NFKB1 (Degree = 20), and TLR4 (Degree = 18).

Identification of the drug-target disease-related genes by taking an intersection of drug target genes and colorectal cancer -related genes (A); Key subnetwork of top 32 nodes analysed (B); GO enrichment analysis of the target genes (C); KEGG enrichment analysis of the target genes (D); Drug-target-pathway-disease network (E).

GO and KEGG analysis

Gene GO function enrichment analysis was performed by uploading 32 key targets to the Sandbox database. These targets were annotated under three GO categories: molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP). The analysis unveiled 1725 BP, 71 CC, and 285 MF terms. The top 10 terms by degree value from each category were visualized using histograms and bubble diagrams. Among the BP, notable enrichments included cellular response to chemical stimulus, response to chemicals/organic substances, positive regulation of metabolic processes (including macromolecule and nitrogen compound metabolism), and stress response. Protein-containing complexes, the endomembrane system, the cytosol, nuclear regions (part, lumen, nucleoplasm), and different extracellular spaces were among the CC with notable enrichments. Important enrichments were found in the following MF: small molecule binding, drug and anion binding, nucleotide/nucleoside phosphate binding, carbohydrate derivative binding, catalytic activity, and various kinds of binding ATP and adenyl nucleotide binding. The highest 10 degree values from each category’s analysis were chosen, plotted, and displayed as bubble diagrams (Fig. 2C). By entering the 32 main targets into the Sandbox database, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was carried out, producing 116 signaling pathways. The annotation of these KEGG pathways and their corresponding putative targets are shown in Table 4. The top 10 enriched KEGG pathways were as follows: cellular senescence, Ras signaling pathway, pancreatic cancer, PD-L1 expression, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, human cytomegalovirus infection, and pathways in cancer (Fig. 2D). A network diagram showing the connections between BZL, 32 important targets, the top 10 signaling pathways, and colorectal cancer was created using the Cytoscape 3.10.2 program (Fig. 2E). The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the initiation and advancement of cancer.

Molecular docking

In order to evaluate the binding interactions between small molecule medications and possible targets and get insight into their therapeutic potential, molecular docking was utilized. Stronger binding affinities are indicated by lower, more negative binding energies, which indicate effective ligand binding to the receptor target protein. We present the findings from the docking of seven diterpenoid compounds with five major targets, whose crystal structures were taken from the PDB database (7AAH for TLR4, 5NJX for HSP90AA1, 1H2M for HIF1A, 8TKL for NFKB1, 6NJS for STAT3). Interestingly, BZL-5 bound well to all of the major targets, including HIF1A. These results imply that BZL may target these proteins to produce anti-colorectal cancer actions. Table 5 summarizes the substances and proteins that were simulated using molecular dynamics. The top 4 binding energies were 7AAH and BZL-2, 7AAH and BZL-5, 1H2M and BZL-4, 1H2M and BZL-5 (Fig. 3) and docking scores ranged from − 6.364 kcal/mol to − 9.989 kcal/mol. Lower docking scores indicate stronger binding affinities, with scores < − 5.0 kcal/mol indicating potential binding and scores < − 7.0 kcal/mol denoting strong binding affinities. Based on the docking results, the top five binding affinities were selected for analysis. For HIF1A, BZL4 and BZL5 exhibited the highest binding affinities with docking scores of − 8.604 kcal/mol and − 9.989 kcal/mol, respectively. For TLR4, the strongest binding ligands were BZL-2 and BZL5, with docking scores of − 9.464 kcal/mol and − 9.974 kcal/mol, respectively. The binding pocket of TLR4 is tightly occupied by BZL-2 and BZL-5, which are stabilized by hydrogen bonding interactions. TLR4 and BZL-2 form hydrogen bonds ARG-163 (2.20 Å), LYS-66 (2.50 Å), ARG-93 (3.10 Å and 3.30 Å). TLR4 and BZL-5 form hydrogen bonds: TYR-58(3.10 Å), ARG-93 (2.60 Å and 2.80 Å). BZL-5 was stably accommodated in the binding pocket of HIF1A, and the binding is stabilized by hydrogen bonding forces. HIF1A forms hydrogen bonds with BZL-4, VAL-242(3.10 Å), ASN-246 (2.20 Å), ASP-243(2.90 Å and 3.40 Å), and lly-99 (2.90 Å). HIF1A and BZL-5 form hydrogen bonds, PRO-333(3.00 Å), GLN-241 (1.90 Å and 2.80 Å) and GLY-337(2.3 Å and 2.80 Å). These results indicated that diterpenoid compounds could effectively bind to the core targets through hydrogen bonding. Notably, BZL-5 exhibited favorable binding to all key targets, particularly with HIF1A.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations are the most reliable method for evaluating the degree to which molecular medicines are binding to significant target proteins. Because of its high binding force, the molecular docking procedure outlined in Table 5 was utilized for molecular dynamics simulations. The state of a protein’s binding to a ligand can be evaluated using five metrics. They are root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), hydrogen bonding (H-Bond), radius of gyration (RG) and free energy landscape map.

A protein’s RMSD displays the shift in location between its original conformation and its conformation during the simulation. The trend of the RMSD of the protein and ligand complexes is another crucial sign of whether the simulation has stabilized. When the upward and downward fluctuations are less than 1 nm, or 1 Å, the simulation is said to have attained a steady state. At the start of the simulation, the BZL-2/7AAH protein complex is in an unstable condition with significant fluctuations, but after 140 ns, it is essentially in a stable form. Overall, the fluctuation range is stable, at no more than 0.1 nm. The BZL-5/7AAH protein complex’s simulated state is insufficiently stable; it is constantly in an unstable state, and the entire process is rife with instability, suggesting that its binding mechanism is not stable. At the start of the simulation, the BZL-4/1H2M protein complex is in an unstable state with significant fluctuations within 70 ns. It begins to stabilize at 70 ns, but at 160 ns it begins to fluctuate a lot until it reaches a pretty steady condition again at 50 ns. There is instability throughout the entire simulation procedure. Following significant oscillations during the first 60 ns of the simulation, the BZL-5/1H2M protein complex started to stabilize at 60 ns and stayed there for a significant period of time, indicating relatively stable binding. In contrast, the BZL-5/1H2M complex has the best binding stability while having the lowest kinematic elasticity of any residue (Fig. 4A).

Molecular dynamics simulations of top binding affinity for BZL-2/TLR4 (7AAH), BZL-5/TLR4 (7AAH), BZL-4/HIF1A (1H2M), BZL-5/HIF1A (1H2M). RMSD Conformational dynamics analysis (A), RMSF Conformational dynamics analysis (B), Rg Conformational dynamics analysis (C), Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between protein-ligand (D), free energy landscape plot (E).

The flexibility and force of motion of protein amino acids during simulations can be described by RMSF, which is the average value of atomic locations across time. In this work, we used RMSF to examine the flexibility of protein amino acids and the relationship between protein flexibility and ligand-binding active amino acids. The 7AAH and BZL-2 complexes have a comparatively high degree of flexibility at the amino acid residues 50–60, 90–120, and 148–165, which serve as active sites for ligand binding. The comparatively flexible residues 50–60, 90–125, and 150–165 of the 7AAH and BZL-5 complex serve as the active sites for ligand binding. The 1H2M and BZL-4 combination exhibits comparatively considerable flexibility at residues 111, 230–250, and 300–340 (the ligand binding active site). The combination of 1H2M and BZL-5 demonstrated comparatively considerable flexibility at the ligand-bound active sites (residues 7-160, 230–250, and 300–350). As can be shown, the RMSF trends for 7AAH and BZL-2, 7AAH and BZL-5 are roughly the same as those for 1H2M and BZL-4 and 1H2M and BZL-5. These two proteins’ flexible distorted regions appear to be as long as the active site and virtually remain unchanged after interacting with ligands (Fig. 4B).

The complex’s RG can be used to characterize the tightness of the protein structure, and it can also be used to characterize how the peptide chains of the proteins fluctuate in tightness and looseness during the course of the simulation. The two proteins’ architecture and characteristics generally stayed the same throughout this simulation (Fig. 4C). Gromacs determines hydrogen bonding using two criteria: hydrogen bond spacing R < = 0.35 nm and angle alpha < = 30° (angle between hydrogen donor and acceptor less than 30°). The system is in a more stable state when there is a significant increase in the number of hydrogen bonds. The stability of the system can also be inferred indirectly from the amount of hydrogen bonds. The 1H2M and BZL-4 complexes (Fig. 4D) generated the most hydrogen bonds during the simulation, suggesting that their systems are comparatively stable. The complexes’ relative free energies, not their absolute free energies, are displayed in the free energy landscape plot. The first two essential elements of the system’s motion, PC1 and PC2, are typically displayed. The trajectory of the system is described by 3 N Cartesian coordinates in ordinary molecular dynamics simulations, which makes it difficult to analyze and assess high-dimensional data. Low-energy conformations, sometimes referred to as optimal conformations, are represented by the low-lying areas in the picture. The size of the low-lying zone increases with simulation stability. The combination of 7AAH and BZL-5 generated the most stable simulations according to the metrics mentioned above (Fig. 4E).

Cell viability assay

We used a CCK-8 assay to look at how BZL-5 affected the viability of CRC (HCT-116). BZL-5 dramatically decreased HCT-116 cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, as seen in Fig. 5A. BZL-5 had strong antiproliferative action in the HCT-116 cell line, and its IC50 was 4.35 µM. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of treating seven cell lines (FHC) with different BZL-5 doses for 24 h is shown in Fig. 5B. The CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the cells’ vitality. It proves that BZL-5 does not significantly harm FHC cells.

Antiproliferative activity of HCT-116 with varying concentrations of BZL-5 (A), cytotoxicity of FHC with varying concentrations of BZL-5 (B), colony formation assay and number of colonies with varying concentrations of BZL-5 (C), scratch wound healing and cell invasion assays and area of migration with varying concentrations of BZL-5 (D), flow cytometry of HCT-116 and cell apoptosis rate of flow cytometry with varying concentrations of BZL-5 (E), mRNA expression of the STAT3, HSP90AA1, HIF1A, NFKB1, TLR4, PIK3CA genes with the 8 µM BZL-5 (F). Note: * represents for vs. CON group (p < 0.05), ** represents for vs. CON group (p < 0.01), *** represents for vs. CON group (p < 0.001), respectively.

Transwell assay

We used a Transwell experiment to investigate how BZL-5 affected these behaviors in HCT-116. The findings demonstrated that BZL-5 inhibits HCT-116 migration in a concentration-dependent manner by causing HCT-116 cells to migrate in smaller numbers from the upper chamber, which lacked serum, to the bottom chamber, which had serum (Fig. 5C).

Wound healing assay

In contrast to BZL-5 (0 µM), it showed considerable healing after 24 h, according to the wound-healing experiment. HCT-116 moved from the intact monolayer to the scratched area when BZL-5 concentrations rose to 2, 4, and 8 µM. The migration rate decreased with increasing BZL-5 concentrations (Fig. 5D), suggesting that BZL-5 markedly and dose-dependently prevented cancer cells from healing.

Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis assay

We used the Annexin V-FITC/PI double-staining technique in flow cytometry to detect apoptosis in order to examine if BZL-5 causes it. The proportion of apoptosis in HCT-116 increased in a dose-dependent manner when compared to the control group, as seen in Fig. 5E.

qRT-PCR

We employed qRT-PCR to measure the expression of markers linked to the STAT3, HSP90AA1, HIF1A, NFKB1, TLR4, PIK3CA and apoptosis following 48 h of treatment with each medication in order to confirm whether BZL-5 caused apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. The mRNA expression of the STAT3, HSP90AA1, HIF1A, NFKB1, TLR4, PIK3CA genes was lower (P < 0.05) in the 8 µM BZL-5-treated group than in the CON group (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

The disease’s variability, sophisticated diagnosis, intricate relationships between genetic and environmental factors, treatment resistance, prognostic constraints, and the lack of adequately safe medications medications confounds research on colorectal cancer. Molecular docking, network pharmacology, and molecular dynamics simulation techniques can be useful for preclinical drug verification, drug screening, and drug mining. We discovered 32 protein targets by network pharmacology screening that may be diterpene targets against colorectal cancer. The top five in terms of degree value were TLR4, NFKB1, HIF1A, HSP90AA1, and STAT3. The likelihood that the protein target is involved in BZL’s pharmacological effect increases with the degree value. Numerous studies have examined the relationship between colorectal cancer and the expression levels of the proteins STAT3, HSP90AA1, HIF1A, and NFKB1, emphasizing their important roles in tumor growth, inflammation, and the cancer microenvironment.

A key player in the biology of cancer, HIF1A (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha) regulates how the body reacts to low oxygen levels. It coordinates multiple vital mechanisms that lead to the advancement of tumors and resistance to treatment26. HIF1A primarily stimulates angiogenesis by upregulating VEGF, which makes it easier for tumors to receive oxygen and nutrients. Furthermore, it promotes metabolic reprogramming, which causes cancer cells to switch from oxygen metabolism to glycolysis, enabling them to survive in low oxygen conditions. By controlling pro-tumorigenic, HIF1A also used to reduce tumor survival and angiogenesis27. Moreover, it affects the immunological landscape of tumors, frequently fostering an immunosuppressive milieu that impedes the effectiveness of anti-tumor responses28. These processes highlight the possibility of using HIF1A targeting in cancer treatment plans to enhance patient outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. We look into how fasting affects the metabolism of glucose and the risk of colorectal cancer. We discover that when CRC cell aerobic glycolysis and proliferation are inhibited, fasting upregulates the expression of a cholesterogenic gene called Farnesyl-Diphosphate Farnesyltransferase 1 (FDFT1). Furthermore, FDFT1 downregulation is associated with poor prognosis and malignant development in colorectal cancer. Furthermore, FDFT1 is an essential tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer. Mechanistically, AKT/mTOR/HIF1α signaling is negatively regulated by FDFT1 to exert its tumor-inhibitory effects. Moreover, fasting and mTOR inhibitors work together to suppress the growth of colorectal cancer29. The above literature indicates that HIF1A plays an important role in the treatment of colon cancer. Compared with normal cells, the expression of HIF1A in colon cancer cell lines is elevated, because the HIF1A pathway is activated, and both positive drugs and traditional Chinese medicines have antagonistic effects on HIF1A. Through the network pharmacological simulation, it was found that a series of compounds isolated from BZL have different degrees of inhibition on HIF1A, suggesting that HIF1A plays an important role in the treatment process, which is worthy of further computer and in vitro experiments.

The results of molecular docking show that HIF1A/BZL-4/BZL-5 and TLR4/BZL-2/BZL-5 interacted closely and both displayed hydrogen bond formation. The stability of a protein-compound complex can be inferred from the stability of RMSD, RMSF, and RG values. Additionally, a higher count of hydrogen bonds typically indicates increased stability of the complex. The most stable binding was revealed by a thorough analysis of the molecular dynamic simulation data involving HIF1A/BZL-5. BZL-5 showed no discernible cytotoxicity in FHC and dramatically decreased the cell survival of HCT-116 in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 value of 4.35 µM, according to the CCK-8 assay. BZL-5 considerably and dose-dependently inhibited cancer cells, according to experimental study using Transwell, wound-healing, and Annexin V-FITC/PI double-staining. qRT-PCR showed that BZL-5 dramatically reduced the levels of STAT3, HSP90AA1, HIF1A, NFKB1, TLR4, PIK3CA. It was established via molecular docking that HIF1A is a significant protein with a therapeutic function. BZL-5 and HIF1A shown a strong ability to interact, molecular dynamics modeling was used to further identify BZL-5 as a potentially significant molecule and to activate the HIF1A pathway by binding with HIF1A, thereby achieving the therapeutic impact of colorectal cancer. In vitro cell tests validated the simulation, demonstrating that BZL-5 had a specific property, the best effect on HCT116 was dose-dependent, and it considerably decreased the proliferation efficiency of colorectal cancer cells. Furthermore, BZL-5 dramatically decreased HCT116’s cell migration and apoptosis. The anti-colorectal cancer effect of BZL-5 via HIF1A pathway was preliminary confirmed by a PCR test, but subsequent work needs to be further verified. Among the isolated compounds, BZL-5 exhibits the most potent anti-CRC activity, possibly attributed to its enhanced formation of stable hydrogen bonds with the HIF1A gene. This interaction potentially augments the binding affinity and activation of the HIF-1 pathway, thereby facilitating its anti-CRC efficacy. Nonetheless, the limited sample size of isolated diterpenoids precludes a comprehensive elucidation. Consequently, additional research is imperative for further investigation.

Following network pharmacological analysis, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and in vitro experimental validation, BZL-5 demonstrated notable anti-CRC efficacy while exhibiting non-toxicity towards normal kidney cells. BZL-5 shows promise as a lead candidate with therapeutic potential by activating the HIF-1 pathway. However, further validation is essential through intricate in vivo animal studies and human trials. Hence, this study represents an initial step towards the development of BZL-5 as a pharmaceutical agent, necessitating additional rigorous experimentation and clinical investigations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, BZL yielded seven common diterpenoids. Although the nuclear parent of these seven compounds are similar, some of them include substituents called nicotinamides that result in diterpenoid alkaloids. However, nicotinamide substituents might not be necessary groups for activity, according to later modeling and verification tests. The HIF1A gene and HIF-1 pathway are crucial for BZL therapy of colorectal cancer, according to molecular docking and molecular dynamics. BZL-5 exhibited potent anti-proliferation action against colorectal cancer cell HCT116, according to preliminary in vitro tests. Additionally, mechanism verification shown that BZL-5 can influence the HIF-1 pathway for therapeutic reasons and reduce tumor survival and angiogenesis. However, further studies are required to establish a definite mechanism. This investigation established a pharmacological basis for the plant’s current clinical use in addition to elucidating its characteristic material base.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript information files.

References

Johdi, N. A. & Sukor, N. F. Colorectal cancer immunotherapy: Options and strategies. Front. Immunol. 11, 1624. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01624 (2020).

Mathey, M. D., Pennella, C. L. & Zubizarreta, P. Colorectal carcinoma in children and adolescents. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 119, e487–e498. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2021.eng.e487 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect and mechanism of Banxia Xiexin decoction in colorectal cancer: A network pharmacology approach. Phytomedicine 123, 155174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155174 (2024).

Lin, F. et al. A network pharmacology approach and experimental validation to investigate the anticancer mechanism and potential active targets of ethanol extract of Wei-Tong-Xin against colorectal cancer through induction of apoptosis via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 303, 115933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115933 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Mechanism of Bazhen decoction in the treatment of colorectal cancer based on network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental validation. Front. Immunol. 14, 1235575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1235575 (2023).

Wu, X., Xu, L. Y., Li, E. M. & Dong, G. Application of molecular dynamics simulation in biomedicine. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 99, 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/cbdd.14038 (2022).

Fan, X. et al. Network pharmacology alliance with experimental validation unveils the anti-colorectal cancer mechanism of Xianlian Jiedu decoction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 342, 119361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2025.119361 (2025).

Dai, W. et al. Anti-colorectal cancer of ardisia gigantifolia Stapf. and targets prediction via network pharmacology and molecular docking study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 23, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-022-03822-8 (2023).

Chen, Q., Rahman, K., Wang, S. J., Zhou, S. & Zhang, H. Scutellaria barbata: A review on chemical constituents, pharmacological activities and clinical applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 26, 160–175. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666191216124310 (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Chemical constituents, anti-tumor mechanisms, and clinical application: A comprehensive review on scutellaria Barbata. Molecules 29, 4134 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29174134 (2024).

Li, H. Y. et al. Phytotoxic neo-clerodane diterpenoids from the aerial parts of scutellaria Barbata. Phytochemistry 171, 112230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112230 (2020).

Shen, J. et al. Traditional uses, ten-years research progress on phytochemistry and pharmacology, and clinical studies of the genus scutellaria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 265, 113198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.113198 (2021).

Amberger, J. S., Bocchini, C. A., Schiettecatte, F., Scott, A. F. & Hamosh, A. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D789–798. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1205 (2015).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: A major update to the drugbank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–d1082. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1037 (2018).

Piñero, J. et al. DisGeNET: A comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D833–d839. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw943 (2017).

Rebhan, M., Chalifa-Caspi, V., Prilusky, J. & Lancet, D. GeneCards: Integrating information about genes, proteins and diseases. Trends Genet. 13, 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01103-7 (1997).

Zhu, W. et al. The use of network pharmacology to investigate the mechanism of action of scutellaria Barbata in the treatment of prostate cancer. J. Men’s Health. 20, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.22514/jomh.2024.065 (2023).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D607–d613. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1131 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Wang, M., Ma, C., Chen, Y., Li, X. & Chen, J. Cytotoxic neo-clerodane diterpenoids from scutellaria Barbata D.Don. Chem. Biodivers. 16, e1800499. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.201800499 (2019).

Zhu, F. et al. Neoclerodane diterpenoids fromscutellaria Barbata. Planta Med. 77, 1536–1541. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1270797 (2011).

Feng, Z. et al. Cytotoxic neoclerodane diterpenoids from scutellaria Barbata. J. Nat. Prod. 73, 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1021/np900309p (2010).

Dai, S. J., Tao, J. Y., Liu, K., Jiang, Y. T. & Shen, L. neo-Clerodane diterpenoids from scutellaria Barbata with cytotoxic activities. Phytochemistry 67, 1326–1330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.024 (2006).

Wu, Q. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors: Master regulators of hypoxic tumor immune escape. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01292-6 (2022).

Mu, G. et al. Calmodulin 2 facilitates angiogenesis and metastasis of gastric cancer via STAT3/HIF-1A/VEGF-A mediated macrophage polarization. Front. Oncol. 11, 727306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.727306 (2021).

Cowman, S. J. & Koh, M. Y. Revisiting the HIF switch in the tumor and its immune microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 8, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2021.10.004 (2022).

Weng, M. L. et al. Fasting inhibits aerobic Glycolysis and proliferation in colorectal cancer via the Fdft1-mediated AKT/mTOR/HIF1α pathway suppression. Nat. Commun. 11, 1869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15795-8 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Kanehisa laboratory to provide KEGG software.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200314), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX24_3662), Ningbo Health Technology Project (2022Y18), and the Research Proiect of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2022FSYYZQ19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: Yuru Yang, Xiaotian Cheng; Acquisition of data: Xiaotian Cheng, Yaonan He; Analysis of data: Yaonan He, Tingting Chen; Interpretation of data: Tingting Chen; Drafting the manuscript: Andong Wang; Revising the manuscript: Di Chen, Andong Wang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Cheng, X., He, Y. et al. Mechanisms of diterpenes from Scutellaria Barbata D. Don against colorectal cancer via network pharmacology and experimental verification. Sci Rep 15, 42779 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27124-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27124-4