Abstract

In the era of the knowledge economy, the competition for talent has intensified, rendering star employees as critical assets for organizations. However, the high performance, status, and social capital of some star nurses may give rise to a sense of psychological entitlement, which in turn can lead to workplace deviance. Based on 438 survey responses, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of such behavior. The research findings are as follows: (1) There is a positive correlation between the star identity of front-line nurses and workplace deviance; (2) Leader - Member Exchange (LMX) serves as a mediator in the relationship between the star identity of front - line nurses and workplace deviance; (3) Psychological entitlement acts as a mediator in the relationship between the star identity of front - line nurses and workplace deviance; (4) Moral disengagement moderates the relationship between the star identity of front-line nurses and workplace deviance. These findings contribute to the theories of social cognition and self-regulation in human resource management by uncovering the cognitive-affective pathways through which star identity leads to deviance. Moreover, they provide managers with practical strategies to reduce deviant behavior and enhance resource utilization among high - performing employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the era of the knowledge economy, the “war for talent” among organizations has intensified, particularly competition over the “critical few” whose contributions are essential for achieving strategic objectives. Organizational management scholars define a small subset of employees who consistently demonstrate high performance and hold significant social status as “star employees”1,2. A growing body of research has examined the impact of star employees in recent years3,4,5,6,7,8,9. On the one hand, star employees constitute a valuable form of human capital that enhances an organization’s core competitiveness and sustainable advantages1,5,10. People often consider them central to the human resource management system, and consequently, they receive numerous benefits, including high salaries11 and ample resources12. Furthermore, star employees act as career mentors3, work assistants13, and role models14, providing substantial direct contributions to organizational outcomes. For instance, in certain fields, the top 5% of star employees frequently account for over 25% of organizational performance15. On the other hand, research also reveals that the influence of star employees is not invariably positive and may produce negative effects in some contexts4,16,17. Existing studies have primarily addressed the detrimental outcomes related to organizational performance and colleague relationships, such as disrupting information flow and workflows18, monopolizing work resources16, impairing team performance4,16, and fostering dependency among peers19.

Workplace deviance encompasses a range of voluntary behaviors that violate organizational norms, policies, or systems, thereby harming the organization or its members. Examples include deliberate procrastination, tardiness, theft or damage of company property, and disrespectful or aggressive conduct toward colleagues20. Such behavior poses a significant threat to the well-being of organizations and their members21,22. In academic research, “workplace deviance” and “counterproductive work behavior (CWB)” are often used interchangeably. Still, a notable conceptual gap exists between them. Workplace deviance is defined by the violation of key organizational or social norms, highlighting the behavior’s “inappropriateness” rather than tangible harm. It centers on rule - breaking. Conversely, CWB focuses more on the actual or potential harm to the organization or its members, such as efficiency loss, resource waste, or well - being impairment. The emphasis is on the negative outcome. All CWBs can be seen as workplace deviance as they violate the norm of employee contribution. However, not all deviant acts are counterproductive. For example, browsing non - work sites during work hours breaks norms but may not cause direct measurable harm. In recent years, organizations have faced considerable challenges due to employee misconduct, with studies indicating escalating costs associated with fraud and unauthorized online activities, resulting in annual losses amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars23. One perspective suggests that individuals adhere to rules due to organizational mechanisms that regulate behavior and enforce conformity within social groups24. When an organization weakens social control, individuals operate without customary restraints, leading to increased violations and deviant behaviors, including workplace deviance. People often refer to star employees as the critical few. They exhibit performance, recognition, status, or social capital that far exceeds that of their peers3, and they contribute disproportionately to organizational output8. They occupy elevated positions within organizations, frequently benefiting from preferential access to resources and opportunities, as well as substantial financial rewards25. Paradoxically, this privileged standing may weaken the social control mechanisms that typically deter deviant behavior.

This analysis pinpoints two significant gaps in current organizational behavior research. On one hand, while the existing literature has thoroughly explored the positive and negative impacts of star employees on their colleagues, it has persistently neglected the likelihood that these esteemed individuals might engage in behaviors that breach organizational norms. This oversight is particularly evident in healthcare settings. On the other hand, nurses shoulder the crucial responsibility of saving lives and delivering care. Those recognized as “stars” for their exceptional skills or dedicated service play central roles in their institutions. However, the paradoxical phenomenon of high - status nurses engaging in workplace deviance remains largely unexplored. In other words, the prevailing theoretical frameworks are inadequate in explaining why individuals who have achieved star status, along with the associated rewards, recognition, and privileges, would undertake actions that could jeopardize their privileged position. To fill these gaps, we propose a theoretical reframing that redirects the focus from “how stars influence others” to “why stars themselves deviate.” From this perspective, we aim to investigate the counterintuitive occurrence of deviance among front - line star nurses, despite their elevated status and access to resources, with the ultimate goal of identifying the key explanatory mechanisms behind this paradox.

Theoretical review and hypothesis development

Theoretical review

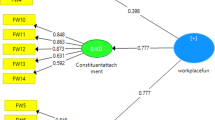

Mischel and Shoda26 pioneered the cognitive-affective processing system (CAPS) theory. This theory posits that external situations and experiential cues can activate an individual’s internal cognitive-affective units, thereby shaping subsequent reactions and behaviors. In this study, the star identity of frontline nurses acts as a crucial situational cue and self-schema, triggering their cognitive-affective processing system. This activation initially promotes the establishment of high-quality leader–member exchange (LMX), which strengthens their perception of privilege within the organizational context. Interpreting such a privileged environment further activates a core affective unit—psychological entitlement, reflecting a persistent belief that one deserves special treatment. Ultimately, whether such cognition and affect lead to workplace deviance depends on activating a key self-regulatory cognitive unit: moral disengagement. When star employees highly activate moral disengagement, they employ cognitive strategies, such as justifying deviant behavior through their superior contributions, to disengage self-regulatory moral controls, thereby facilitating norm-violating behaviors.

Graen and Uhl-Bien27,28 developed the LMX theory, which explains how leaders form differentiated exchange relationships with subordinates. In this study, star employees typically establish high-quality LMX relationships and receive more trust, resources, and autonomy from leaders29,30. Although people often associate these relationships with positive outcomes—including improved job performance and organizational citizenship behavior31,32,33—this study focuses on their potential negative implications. High-quality LMX may produce a sense of privilege and exceptionalism, which fosters entitled cognition and reduces compliance with organizational norms. As favored “insiders,” star employees may perceive immunity from normal constraints, thereby increasing their likelihood of engaging in deviant behaviors such as absenteeism, resource misuse, or other ethical violations34,35.

Hobfoll36 originally proposed the conservation of resources (COR) theory, arguing that individuals strive to acquire, retain, and safeguard valuable resources. Owing to their high status and performance, star employees often possess more tangible and intangible resources. However, COR theory suggests that perceived threats of resource loss can prompt defensive or entitled actions36. In this study, the resource advantage and social capital linked to star identity intensify psychological entitlement, which Campbell et al.37 conceptualize as a stable belief in one’s deservingness of special treatment8,38. This heightened entitlement motivates individuals to protect and expand their resource gains, even if doing so entails engaging in deviant behavior39,40.

Hirschi41 advanced social control theory, emphasizing how internal and external controls prevent deviant behavior. In organizations, social control integrates structural constraints and individual moral agency42. In this research, moral disengagement—a concept deriving from Bandura’s social cognitive theory—functions as a failure of internal moral control43,44,45. It comprises cognitive mechanisms through which individuals rationalize and excuse norm-violating actions by redefining morality, distorting consequences, or shifting responsibility46. For star employees, high moral disengagement weakens self-imposed moral constraints, enabling workplace deviance without expected guilt or shame and thereby representing a breakdown of social control.

We integrate these theoretical perspectives within a CAPS-guided moderated mediation model. CAPS provides the overarching framework, tracing the process from the situational trigger (star identity) to the behavioral outcome (deviance) through cognitive-affective mediation. LMX theory offers a relational explanation for how perceptions of privilege form; COR theory clarifies the motivational role of psychological entitlement in resource-driven behaviors; and social control theory explains the moral-cognitive regulation mechanism of moral disengagement. Together, these theories provide a multilayered, theoretically grounded account of why and when star nurses engage in workplace deviance.

Star employees and workplace deviance

The star identity, which organizations confer as a scarce and fluid characteristic, compels employees who attain it to actively protect and maintain this status. These employees strive to meet the expectations linked to this identity while also managing potential identity threats47. In the workplace, star employees primarily face identity threats from three sources. First, the threat stems from high performance. Because leaders recognize star employees for their exceptional performance, they often hold heightened performance expectations for them5,10,48. However, since work performance follows the law of diminishing returns, star employees—who already achieve outstanding results—must expend even greater effort to surpass their current achievements. Second, the threat arises from visibility. Star employees enjoy high visibility, which attracts significant attention both within and outside the organization14. Other organizational members constantly scrutinize their actions49, compelling them to engage in more surface acting. Because outward expressions often conflict with genuine feelings, surface acting frequently accompanies emotional disturbances50. Finally, abundant social capital poses a threat. Star employees typically possess substantial social capital, which leads others to rely heavily on them for assistance3. When star employees confront these identity threats, they experience considerable coping pressure. According to the COR Theory, individuals must actively mobilize resources to tackle challenging tasks and difficulties. If they fail to manage these effectively, significant stress may result, leading to continuous depletion of physical and mental resources51. This, in turn, triggers negative emotions, fatigue, insomnia, and other adverse effects. Additionally, such stress can provoke emotional and behavioral responses52, such as tardiness, absenteeism, or job-hopping, and even more severe negative behaviors like interpersonal aggression, incivility, complaints, sabotage, and theft53. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: A positive correlation exists between the star identity of frontline nurses and workplace deviance.

The mediating role of LMX

In organizations, the outstanding performance and social status of star employees provide essential support to their teams. This support not only helps teams complete tasks efficiently and effectively but also enhances their overall reputation and access to external resources1,15. Moreover, power and status significantly influence resource allocation in hierarchical organizations, and leaders hold an advantage over subordinates in these areas54,55. If subordinates wish to obtain more resources, they proactively increase their willingness to collaborate with leaders. Consequently, leaders and subordinates align their goals more closely in terms of completing team tasks and improving team performance. In other words, both leaders and star employees strongly desire to enhance cooperation, which lays the foundation for building high-quality leader-member relationships.

However, high-quality LMX relationships can weaken the leader’s social control over employees. Objectively, such relationships reduce the deterrent effect of the leader’s formal power over employees56, including creating ambiguity regarding the certainty and severity of punishment24. In this situation, leaders, considering organizational performance, find it difficult to make reasonable decisions about star employees’ workplace deviance and tend to avoid conflict with them57. This decrease in the certainty and severity of punishment leads star employees to perceive that deviations are tolerated. Subjectively, high-quality LMX relationships bring leaders and employees closer socially, making it challenging for leaders to evaluate employees objectively and fairly58. For example, leaders may exhibit attribution biases toward employees with whom they have better exchange relationships. When employees display workplace deviance (such as tardiness, absenteeism, or early departures), leaders are more likely to attribute the causes to external factors rather than internal factors like poor attitudes59,60. When star employees perceive this attribution bias, the leader’s social control over them diminishes further, resulting in increased workplace deviance. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: LMX acts as a mediator in the relationship between the star identity of front-line nurses and workplace deviance.

The mediating role of psychological entitlement

According to the cognitive-affective processing system theory, individuals possess two parallel modes of behavioral response: the “hot processing system,” which centers on emotional impulsivity, and the “cold processing system,” which centers on rational cognition. The hot system processes personal emotions automatically; when external situational stimuli activate emotions, this internal system triggers impulsive responses reflexively. By contrast, the cold system supports controllable responses, meaning individuals can cognitively process external situational stimuli, shaping their subsequent behavior. In practice, when people believe they have made significant contributions to the organization, they may exaggerate their contributions’ importance and feel entitled to receive more61. Star employees may also experience psychological entitlement. First, their unique skills may lead them to deliberately exaggerate the novelty of their contributions, leading them to perceive themselves as distinctively superior to ordinary employees, thereby fostering a sense of superiority62. Second, high visibility and social capital allow star employees to control substantial critical resources within the organization; they believe they can decide how and when to share these resources3,12. Finally, star employees often attribute their good fortune—such as high performance—to their own merits rather than to those of ordinary employees63,64. These tendencies may encourage self-serving biases, leading star employees to credit their successes to themselves, reinforcing their belief that they deserve greater rewards from the organization. As a result, frontline star nurses may feel they should receive more rewards than ordinary nurses, leading to psychological entitlement.

Psychological entitlement among star employees often correlates with negative work outcomes. First, it can produce unrealistically high cognitive expectations65. Inflated self-perceptions lead employees to expect more rewards, recognition, and positive interpersonal treatment66. When reality does not meet these expectations, individuals experience a strong sense of unfairness. This emotional state distorts their perception of reciprocity, ultimately sparking workplace deviance67. Second, psychological entitlement reinforces self-serving attribution biases in star employees66. This biased thinking leads them to expect preferential treatment, so they regard their own workplace deviance as acceptable. Furthermore, psychological entitlement can lead star employees to adopt looser moral standards. They rationalize their deviant behaviors, believing they have a right to violate moral norms40, which allows them to act without guilt68. Empirical research also shows that psychological entitlement can breed disrespect for others69, reduce helping behaviors70, increase dishonesty71, and even escalate conflicts with supervisors72. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Psychological entitlement functions as a mediator in the relationship between the star identity of front-line nurses and workplace deviance.

The moderating role of moral disengagement

Moral disengagement refers to an individual’s cognitive restructuring process that justifies immoral behavior, and it varies across individuals73,74. When a person’s moral disengagement mechanism activates, they rationalize immoral conduct through moral justification, euphemistic labeling, and advantageous comparison. They also diffuse and transfer responsibility via external attributions, downplaying the harm of immoral actions and even dehumanizing victims while blaming them75. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of moral disengagement tend to justify workplace deviance morally and activate mechanisms that diffuse and transfer responsibility, thereby impairing moral self-regulation. This reduction manifests as diminished moral condemnation and less guilt when engaging in workplace deviance76. Consequently, the “soft control” that the organizational environment exerts on employees weakens further, making employees more prone to workplace deviance amid moral dilemmas. Conversely, employees with lower levels of moral disengagement are more likely to uphold moral standards, reduce responsibility diffusion and transfer, and significantly decrease their likelihood of engaging in workplace deviance. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Moral disengagement moderates the relationship between the star identity of frontline nurses and workplace deviance, such that the positive relationship is stronger when moral disengagement is high.

The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Data collection

We collected data from January 12, 2024, to April 24, 2024, using a questionnaire survey. The questionnaire comprised two parts. The first part explained the purpose and significance of the research and assured participants that their data would serve scientific research only, not commercial applications. We also included an informed consent clause at the end of this section to ensure that every participant provided informed consent. The second part contained various variables, and we randomized the item sequence to reduce guesswork by respondents. We selected a total of 30 hospitals for data collection. Geographically, these hospitals were located in 8 regions of China, 4 in Thailand, 4 in Malaysia, 4 in Kazakhstan, 4 in the United States, 3 in the UK, and 3 in New Zealand. Before collecting data, the Ethics Committee of the School of Business Administration at Henan University of Animal Husbandry and Economy reviewed and approved this study (Approval No. EA2024029).

To overcome geographical constraints, we used an online data collection method. We first contacted friends, classmates, or acquaintances working at the target hospitals. With their consent, we distributed survey links and asked them to invite nurses who met the following criteria: their head nurses or unit managers had formally nominated them as top 5–10% performers within their unit, and institutional metrics had objectively verified their excellence—such as patient satisfaction scores related to their care, volume of specialized procedures performed, and low medical error rates. To encourage participation, we offered a small gift to each respondent who completed the survey. We distributed 540 questionnaires and received 476 responses. After excluding surveys with errors or missing information, we retained 438 valid surveys. Among these nurses, 174 (39.7%) held a diploma or below, 211 (48.2%) had a bachelor’s degree, 45 (10.3%) had a master’s degree, and 8 (1.8%) had a doctorate; 208 (47.5%) had worked for 5 years or less, 152 (34.7%) for 5 to 10 years, and 78 (17.8%) for over 10 years; the average age was 26.5 years (SD 3.4).

Measure

We measured star employees using the scale developed by Call et al.2, which covers three dimensions: high performance, high visibility, and high social capital, with a total of 26 items. Representative items include: “Compared to my colleagues, I can better complete the tasks assigned by my superiors,” “In the hospital, leaders and colleagues know my work reputation,” and “I spend time developing relationships with people outside my department.”

We assessed LMX using a 4-item scale adapted from Janssen and Van Yperen77. A sample item is: “I trust my superior leader and support their decisions.”

To measure psychological entitlement, we employed the 4-item Psychological Entitlement Scale developed by Yam et al.68. Example items include: “I genuinely feel that I should enjoy more rights than other colleagues.”

We evaluated moral disengagement with a short form of the scale introduced by Moore et al.78, which contains 5 items. One example is: “It is acceptable to spread rumors to protect those you care about.”

For workplace deviance, we used the 5-item scale from Qin et al.20. A sample item reads: “I often arrive late without permission.”

All items used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Tools

In this study, data analysis was conducted using the open-source R package “lavaan” (version 0.6.17).

Sample common method bias test

To address potential common method bias, we introduced a common method factor using the latent error variable control approach. Our results show that including this factor improved the overall model fit. Specifically, RMSEA decreased by 0.01 and SRMR dropped by 0.02, while CFI increased by 0.02. Furthermore, Harman’s single-factor test showed that the first factor explained only 39.15% of the total variance. Together, these findings indicate that common method variance did not substantially affect the results, which supports the statistical robustness of the model.Results.

Reliability and validity

Table 1 presents the factor loadings, all of which exceeded 0.60. Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.81 to 0.86, indicating good reliability. Additionally, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct surpassed 0.50, meeting the acceptable threshold for convergent validity. As Table 2 shows, the square root of the AVE for each variable was greater than its correlation with any other variable, thereby supporting discriminant validity.

Model fit

The model fit indices were χ2/df = 2.84, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07, and SRMR = 0.06, demonstrating that the model exhibited a good fit.

Mediating effect

As summarized in Table 3, the total effect of star identity on workplace deviance was significant (β = 0.29, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). The direct effect also reached significance (β = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1). Furthermore, we identified two significant indirect effects: the path through LMX was significant (β = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01), supporting H2; and the path through psychological entitlement was also significant (β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001), supporting H3. Bootstrap analysis with 5,000 iterations confirmed that the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for both indirect effects excluded zero, further validating the mediating roles of LMX and psychological entitlement.

Moderating effect

Table 4 demonstrates a significant interaction effect between star identity and moral disengagement (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, p < 0.05), indicating that moral disengagement moderates the relationship between star identity and workplace deviance among frontline nurses, thus supporting H4.

To further interpret this interaction, we conducted a simple slopes analysis. The results revealed that for nurses with high moral disengagement (+ 1 SD), the positive effect of star identity on workplace deviance was stronger (simple slope = 0.39, p < 0.001). For nurses with low moral disengagement (–1 SD), the relationship remained significant but weaker (simple slope = 0.17, p < 0.05). Figure 2 visually presents this pattern, clearly illustrating that as moral disengagement increases, the relationship between star identity and workplace deviance becomes steeper, suggesting that higher levels of moral disengagement amplify the effect of star identity on deviance.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine why frontline star nurses, despite their elevated status and resources, engage in workplace deviance. Guided by the CAPS theory, we tested a model incorporating mediating and moderating mechanisms to explain this paradoxical phenomenon. The findings align coherently with the CAPS framework, illustrating how star identity—functioning as a salient situational cue and self-schema—activates a sequential chain of cognitive–affective units, namely LMX and psychological entitlement, ultimately resulting in deviant behavior, particularly under conditions of high moral disengagement.

First, we identified a significant positive correlation between star identity and workplace deviance. Within the CAPS framework, star identity serves not only as an external marker of status but also as an internalized self-schema that guides cognition and behavior. According to COR theory, employees strongly motivate themselves to protect and maintain this valued identity once acquired47. When star nurses encounter identity-related threats, performance pressures, or challenges to their status, they experience heightened stress and accelerated resource depletion51. This resource loss predisposes them to negative emotional and behavioral outcomes52,53, including various forms of workplace deviance as a maladaptive coping response.

Second, our research confirmed the important mediating roles of both LMX and psychological entitlement. High-performing star employees often establish high-quality LMX relationships1,15, characterized by greater trust, support, and resource exchange with leaders. Although beneficial in many respects, these differentiated relationships can reduce perceived supervisory monitoring and weaken leaders’ enforcement of normative controls24,57,58, thereby creating perceived impunity. Furthermore, this relational privilege reinforces the individual’s perception of being “special,” activating a core affective unit within the CAPS framework: psychological entitlement. Here, individuals develop a stable belief that they deserve exemptions and preferential treatment61, which fosters justifications for engaging in norm-violating behaviors69,70,71.

Finally, moral disengagement—a key self-regulatory cognitive mechanism rooted in social cognitive theory74—significantly moderated the relationship between star identity and deviance. When highly activated, moral disengagement leads star employees to engage in cognitive restructuring processes such as moral justification, diffusion of responsibility, and distortion of consequences76. This process effectively neutralizes their internal moral controls and weakens the restraining power of organizational and social constraints. These findings match social control theory, emphasizing that the interaction between internal cognitive mechanisms and external situational controls jointly shapes behavioral outcomes.

Theoretical contributions

-

(1)

We adopt a perspective centered on frontline star nurses to explore the relationship between star identity and workplace deviance, which encompasses individual negative behaviors. Star employees represent a highly valuable form of human capital1,5,10, and existing research predominantly investigates their positive impacts on organizations3,13,14. Few studies that focus on the negative effects of star employees primarily emphasize their impact on organizational performance and colleague relationships4,16,19, but researchers have conducted relatively little study on the negative behavioral impacts on the star employees themselves. Our findings demonstrate that the star identity of frontline nurses may lead to workplace deviance, offering a new perspective for research on star employees.

-

(2)

Drawing on the CAPS theory, LMX theory, and social control theory, we examine the mediating mechanism linking star identity and workplace deviance among frontline nurses. On one hand, star employees typically bring high performance to the organization1,15, facilitating the establishment of high-quality leader-member exchange relationships, which subsequently weakens the social control that leaders exert over employees24,57,58. Additionally, when star employees perceive that they have made significant contributions to the organization, they feel entitled to more61, leading to psychological entitlement and fostering negative behaviors69,70,71. On the other hand, moral disengagement influences employee behavior through individuals’ subjective interpretations of objective conditions74. When frontline nurses exhibit a higher level of moral disengagement, they more readily justify workplace deviance on moral grounds and diffuse responsibility, thereby weakening the “soft control” that the organizational environment imposes on employees. Conversely, when moral disengagement levels are lower, the opposite effect occurs.

Practical implications

-

(1)

Hospitals should address star employees appropriately. While establishing star nurses as role models to leverage their motivational effects, they must also monitor their psychological dynamics. As “center stage” employees, these individuals inevitably attract more attention, with others scrutinizing their every word and action, which silently places significant pressure on them. Therefore, hospitals ought to implement effective support plans that enhance star employees’ emotional regulation and psychological counseling, strengthen their ability to cope with workplace stress and negative emotions, help them effectively handle negative incidents, and prevent the spread of workplace anxiety and subsequent negative behaviors.

-

(2)

Leaders should recognize the potential negative impacts of high quality LMX. In such exchanges, star nurses often become leader “insiders,” showing strong loyalty and making extra contributions. In return, leaders greatly trust them, listen more to their advice, and offer both life and work support. However, during this process, “insiders” may perceive that leaders tolerate their workplace deviance, which encourages them to engage in such behaviors. Therefore, hospital leaders at all levels should consciously manage their relationships with star nurses. Regardless of the LMX quality, all actions must adhere to organizational rules and regulations, with clear rewards and penalties in place.

-

(3)

To mitigate psychological entitlement among star employees, organizations should first set clear expectations by defining the responsibilities, roles, and performance standards for all nurses, including stars, to prevent misconceptions about status or privileges. Second, they should encourage humility and gratitude by promoting these values within the organization, recognizing contributions from all team members, not only star nurses, to emphasize teamwork. Third, organizations ought to monitor and address privileged behaviors by closely observing star nurses’ actions and intervening promptly through one on one conversations, counseling, or other necessary measures. These steps help create a harmonious and efficient hospital work environment.

-

(4)

Hospitals can enhance the moral standards of star nurses through several measures. First, they should strengthen moral education and training by regularly offering courses on ethics and professional conduct, especially for star nurses. Second, cultivating a team culture that emphasizes teamwork, respect, and mutual assistance is essential. Third, providing regular feedback and guidance helps star nurses align their behavior with hospital moral standards. Fourth, establishing role models by recognizing and commemorating nurses who demonstrate high moral behavior encourages star nurses to uphold higher standards. Fifth, prioritizing mental health support for star nurses prevents moral decline due to stress and burnout.

-

(5)

Preventing and managing workplace deviance among star employees requires clear rules and regulations. Hospitals should formulate explicit policies and codes of conduct so all employees understand acceptable and unacceptable behavior. They should also strengthen communication and feedback mechanisms, encouraging open dialogue where employees can comfortably express opinions and concerns. Regularly conducting performance evaluations and feedback helps promptly identify and correct deviance. Offering training on professional ethics and compliance enhances employees’ moral awareness and responsibility. Finally, designing incentive mechanisms that value both individual achievement and teamwork reduces excessive competitive pressure and discourages workplace deviance.

Limitations and future research directions

First, although we used cross-sectional data and conducted rigorous empirical analysis, this approach inherently limits our ability to establish causal relationships between variables. To enhance the validity and capture temporal dynamics of the proposed model, future research should adopt longitudinal and experience-sampling designs. For example, longitudinal field studies that track star employees over time could clarify how changes in moral disengagement or psychological entitlement influence subsequent deviant behaviors. Additionally, experience sampling methodology would allow researchers to capture within-person fluctuations in entitlement and deviance across situations and time, offering finer-grained insights into real-time psychological mechanisms underlying these behaviors.

Second, although we established a research model to explore the internal mechanisms of workplace deviance among frontline star nurses, several questions remain for future investigation. These include whether distinct subgroups exist within the sample, whether these subgroups yield different conclusions, and whether individuals transition between profiles over time. Subsequent studies should further examine these aspects using person-centered approaches such as latent profile analysis and latent transition analysis.

Third, diverse cultural traditions and social customs can significantly influence individual behavioral choices. Although we utilized a multi-country sample to enhance the generalizability of our findings, we did not examine how cultural differences, such as power distance or individualism, might shape the outcomes. These factors may substantially influence the development and expression of leader-member exchange and psychological entitlement. Future research should integrate cultural dimensions into the theoretical framework, for instance by testing the moderating role of cultural values or conducting multi-group comparisons of structural paths across cultural contexts. Researchers should also employ cross-cultural measurement invariance testing and culturally stratified sampling to strengthen the robustness and depth of future findings.

Fourth, although we employed a multi-method approach integrating supervisor nominations, self-reported star identity, and objective performance indicators to operationalize star employees, each method has inherent limitations. Supervisor evaluations may suffer from interpersonal bias or vary in cross-team comparability. Self-report measures, even when based on established scales, remain vulnerable to self-enhancement and social desirability biases. Although we included objective metrics to triangulate the results, the availability and interpretation of such data can differ across organizations and settings. Future research could improve the measurement of star identity by incorporating peer assessments, adopting more granular and standardized performance benchmarks, or developing integrated metrics from multiple sources.

Conclusion

The results demonstrate that star identity acts as a salient situational cue that triggers a sequential mediation process through both LMX and psychological entitlement, ultimately leading to deviant behavior. Moral disengagement significantly moderates this relationship by weakening self-regulatory processes and amplifying the effect of star identity on deviance. These findings substantially extend human resource management theory by integrating social-cognitive and self-regulatory perspectives into research on high-status employees. From a practical standpoint, we recommend a balanced approach to managing star employees that recognizes their contributions while maintaining clear ethical accountability. Organizations should implement supportive leadership practices along with targeted interventions to reduce moral disengagement and mitigate entitlement perceptions. By addressing both relational and cognitive mechanisms, healthcare institutions can more effectively reduce workplace deviance while preserving the valuable contributions of star employees.

Data availability

Available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SE:

-

Star employees

- LMX:

-

Leader—member exchange

- PE:

-

Psychological entitlement

- MD:

-

Moral disengagement

- WD:

-

Workplace deviance

References

Kehoe, R. R., Lepak, D. P. & Bentley, F. S. Let’s call a star a star: task performance, external status, and exceptional contributors in organizations. J. Manag. 44 (5), 1848–1872 (2018).

Call, M. L., Nvberg, A. J. & Thatcher, S. M. B. Stargazing: an integrative conceptual review, theoretical reconciliation, and extension for star employee research. J. Appl. Psychol. 100 (3), 623–640 (2015).

Asgari, E. et al. Red giants or black holes? The antecedent conditions and multilevel impacts of star performers. Acad. Manag. Ann. 15 (1), 223–265 (2021).

Call, M. L., Campbell, E. M., Dunford, B. B., Boswell, W. R. & Boss, R. W. Shining with the stars? Unearthing how group star proportion shapes non-star performance. Pers. Psychol. 74 (3), 543–572 (2021).

Barlow, M. A., Hesterly, W. S. & Verhaal, J. C. Catching a falling star: mobility of declining star performers, peer efects, and organizational performance in the National football league. J. Bus. Res. 165, 114053 (2023).

Villamor, I. & Aguinis, H. Think star, think men? Implicit star performer theories. J. Organiz. Behav. 45, 6 (2024).

Kehoe, R. R., Collings, D. G. & Cascio, W. F. Simply the best? Star performers and high potential employees: critical refections and a path forward for research and practice. Pers. Psychol. 76 (2), 585–615 (2023).

Aguinis, H. & O’Boyle, E. Star performers in twenty-frst century organizations. Pers. Psychol. 67 (2), 313–350 (2014).

Groysberg, B. & Lee, L. E. Star power: colleague quality and turnover. Ind. Corp. Change. 19 (3), 741–765 (2010).

Kim, J. & Makadok, R. Where the stars still shine: some efects of star-performers-turned-managers on organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 43 (12), 2629–2666 (2022).

Terry, R. P., McGee, J. E., Kass, M. J. & Collings, D. G. Assessing star value: the infuence of prior performance and visibility on compensation strategy. Hum. Resource Manage. J. 33 (2), 307–327 (2023).

Li, Y., Li, N., Li, C. & Li, J. The Boon and Bane of creativestars: a social network exploration of how and when team creativity is (and is not) driven by a star teammate. Acad. Personality Social Psychol. 71 (1), 91–103 (2020).

Oettl, A. Reconceptualizing stars: scientist helpfulness and peer performance. Manage. Sci. 58 (6), 1122–1140 (2012).

Downes, P. E., Crawford, E. R., Seibert, S. E., Stoverink, A. C. & Campbell, E. M. Referents or role models? The self-efficacy and job performance efects of perceiving higher performing peers. J. Appl. Psychol. 106 (3), 422–438 (2021).

O’Bovle, E. & Aguinis, H. The best and the rest:revisiting the norm of normality of individual performance. Pers. Psychol. 65 (1), 79–119 (2012).

Chen, J. S. & Garg, P. Dancing with the stars: Benefts of a star employee’s temporary absence for organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 39 (5), 1239–1267 (2018).

Prato, M. & Ferraro, F. Starstruck: how hiring high-status employees afects incumbents’ performance. Organ. Sci. 29 (5), 755–774 (2018).

Overbeck, J. R., Correll, J. & Park, B. Internal Status Sorting in Groups: the Problem of Too Many Stars (Elsevier, 2005).

Kehoe, R. R. & Tzabbar, D. Lighting the way or stealing the shine? An examination of the duality in star scientists’ efects on Frm innovative performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 36 (5), 709–727 (2015).

Qin, X., Chen, C. & Yam, K. C. The double-edged sword of leader humility: investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 105 (7), 693–712 (2020).

Ferris, D. L., Spence, J. R., Brown, D. J. & Heller, D. Interpersonal injustice and workplace deviance: the role of esteem threat. J. Manag. 38 (6), 1788–1811 (2012).

Robinson, S. L. & Bennett, R. J. A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: a multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manag. J. 38 (2), 555–572 (1995).

Lian, H., Ferris, D. L. & Brown, D. J. Does taking the good with the bad make things worse? How abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to impact need satisfaction and organizational deviance. Organiz. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 117 (1), 41–52 (2012).

Cheng, L., Li, Y., Li, W., Holm, E. & Zhai, Q. Understanding the violation of is security policy in organizations: an integrated model based on social control and deterrence theory. Comput. Secur. 39 (1), 447–459 (2013).

Malhotra, P. & Singh, M. Indirect impact of high performers on the career advancement of their subordinates. Hum. Resource Manage. Rev. 26 (3), 209–226 (2016).

Mischel, W. & Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 102 (2), 246–268 (1995).

Dansereau, F., Graen, G. & Haga, W. J. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: a longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organiz. Behav. Hum. Perform. 13 (1), 46–78 (1975).

Graen, G. B. & Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Quart. 6 (2), 219–247 (1995).

Liden, R. C., Erdogan, B. & Sparrowe, W. R. T. Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: implications for individual and group performance. J. Organiz. Behav. 27 (6), 723–746 (2010).

Erdogan, B. & Bauer, T. N. Differentiated leader-member exchanges: the buffering role of justice climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 95 (6), 1104–1120 (2010).

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L. & Ferris, G. R. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J. Manag. 38 (6), 1715–1759 (2012).

Gottfredson, R. K., Wright, S. L. & Heaphy, E. D. A critique of the leader-member exchange construct: back to square one. Leadersh. Q. 31 (6), 101–385 (2020).

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M. & Liden, R. C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: a social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 40 (1), 82–111 (1997).

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Bonner, J. M., Webster, B. D. & Kim, J. Supervisor expediency to employee expediency: the moderating role of leader–member exchange and the mediating role of employee unethical tolerance. J. Organiz. Behav. 39 (4), 525–541 (2018).

Lin, Y. & Cheng, K. Leader-member exchange and employees′ unethical pro-organizational behavior: a differential mode perspective. J. Manage. Sci. (Chinese). 29 (5), 57–70 (2016).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44 (3), 513–524 (1989).

Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J. & Bushman, B. J. Psychological entitlement: interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J. Pers. Assess. 83 (1), 29–45 (2004).

Wang, H., Zou, C. & Cui, Z. The influence of differential leadership to bootleg innovation: a moderated mediation model. Sci. Technol. Progress Policy (Chinese). 35 (9), 131–137 (2018).

Chen, C., Zhang, Z. & Jia, M. Research on the dark side of stretch goals: a moderated mediation model based on psychological licensing theory. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manage. (Chinese). 35 (04), 72–80 (2021).

Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A. & Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics. 154 (1), 109–126 (2019).

Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency (University of California Press, 1969).

Chua, C. E. H. & Myers, M. D. Social control in information systems development: a negotiated order perspective. J. Inform. Technol. 33 (3), 173–187 (2018).

Bandura, A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Moral. Educ. 31 (2), 101–119 (2002).

Detert, J. R., Trevin, L. K. & Sweitzer, V. L. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 (2), 374–391 (2008).

Moore, C. Moral disengagement in processes of organizational corruption. J. Bus. Ethics. 80 (1), 129–139 (2008).

Smith, P. K. et al. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 49 (4), 376–385 (2008).

Petriglieri, J. L. Under threat: responses to and the consequences of threats to individuals’ identities. Acad. Manage. Rev. 36 (4), 641–662 (2011).

Jacobsen, C. B. & Andersen, L. B. High performance expectations: concept and causes. Int. J. Public. Adm. 42 (2), 108–118 (2019).

Lam, C. K., Van dVGS, Walter, F. & Huang, X. Harming high performers: a social comparison perspective on interpersonal harming in work teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 96 (3), 588–601 (2011).

Grandey, A. A. & Gabriel, A. S. Emotional labor at a crossroads: where do we go from here? Annu. Rev. Organiz. Psychol. Organiz. Behav. 2 (1), 323–349 (2015).

Zhang, K., Lu, G. & Wang, J. Job stress and job burnout: the path model of mediating effect of psychological capital. Stud. Psychol. Behav. (Chinese). 1, 91–96 (2014).

Zhu, R., Chen, X. & Peng, L. The effects of emotional intelligence on job performance: an analysis of the job stress as a mediator. J. Stat. Inform. (Chinese). 2, 104–108 (2013).

Zhang, Y. & Chen, W. The research of the relationship between job stress and employee workplace deviance. East. China Econ.Manage. (Chinese). 10, 90–94 (2008).

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H. & Anderson, C. Power,approach, and Inhibition. Psychol. Rev. 110 (2), 265–284 (2003).

Maner, J. K. & Mead, N. L. The essential tension between leadership and power: when leaders sacrifice group goals for the sake of self-interest. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 99 (3), 482–497 (2010).

Wenzel, M. The social side of sanctions: personal and social norms as moderators of deterrence. Law Hum. Behav. 28 (5), 547–567 (2004).

Ren, S. & Chadee, D. Is Guanxi always good for employee self-development in china? Examining non-linear and moderated relationships. J. Vocat. Behav. 98 (10), 108–117 (2017).

Hong, Y., Pavlou, P. A., Wang, K. & Shi, N. On the role of fairness and social distance in designing effective social referral systems. MIS Q. 41 (3), 787–809 (2017).

Duarte, N. T., Goodson, J. R. & Klich, N. R. Effects of dyadic quality and duration on performance appraisal. Acad. Manag. J. 37 (3), 499–521 (1994).

Heneman, R. L., Greenberger, D. B. & Anonyuo, C. Attributions and exchanges: the effects of interpersonal factors on the diagnosis of employee performance. Acad. Manag. J. 32 (2), 466–476 (1989).

Graffin, S. D., Bundy, J., Porac, J. F., Wade, J. B. & Quinn, D. P. Falls from grace and the hazards of high status: the 2009 British Mp expense scandal and its impact on parliamentary elites. Adm. Sci. Q. 58 (3), 313–345 (2013).

Sachdeva, S., Iliev, R. & Medin, D. L. Sinning saints and saintly sinners: the paradox of moral self-regulation. Psychol. Sci. 20 (4), 523–528 (2009).

Anderson, L. S. & Heyne, L. A. Flourishing through leisure: an ecological extension of the leisure and well-being model in therapeutic recreation strengths-based practice. Therapeut. Recreation J. 46 (2), 121–140 (2012).

Fast, N. J., Sivanathan, N., Mayer, N. D. & Galinsky, A. D. Power and overconfident decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum Decis. Process. 117 (2), 249–260 (2012).

Jordan, P. J., Ramsay, S. & Westerlaken, K. M. A review of entitlement: implications for workplace research. Organiz. Psychol. Rev. 7 (2), 122–142 (2017).

Harvey, P. & Martinko, M. J. An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. J. Organiz. Behav. 30 (4), 459–476 (2009).

Zhang, Y., Shang, G., Zhang, J. & Zhou, F. Perceived overqualification and employee job performance: a perspective of psychological entitlement. Manage. Rev. (Chinese). 31 (12), 194–206 (2019).

Yam, K. C., Klotz, A. C., He, W. & Reynolds, S. J. From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Acad. Manag. J. 60 (1), 373–396 (2017).

Twenge, J. M. & Campbell, S. M. Generational differences in psychological traits and their impact on the workplace. J. Manager. Psychol. 23 (8), 862–877 (2008).

Zitek, E. M., Jordan, A. H., Monin, B. & Leach, F. R. Victim entitlement to behave selfishly. J. Personality Social Psychol. 98 (2), 245–255 (2010).

Vincent, L. C. & Kouchaki, M. Creative, rare, entitled, and dishonest: how commonality of creativity in one’s group decreases an individual’s entitlement and dishonesty. Acad. Manag. J. 59 (4), 1451–1473 (2016).

Laird, D. M., Harvey, P. & Lancaster, J. Accountability, entitlement, tenure, and satisfaction in generation Y. J. Managerial Psychol. 30 (1), 87–100 (2015).

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V. & Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in exercise of moral agency. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 71 (2), 364–374 (1996).

Bandura, A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of illhumanities. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 3 (3), 193–209 (1999).

Newman, A., Le, H., North-Samardzic, A. & Cohen, M. Moral disengagement at work: a review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics. 167 (2), 535–570 (2020).

Samnani, A-K., Salamon, S. D. & Singh, P. Nagative affect and counterproductive workplace buhavior: the moderating role of moral disengagement and gender. J. Bus. Ethics 119 (2), 235–244 (2014).

Janssen, O. & Yperen, N. W. V. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 47 (3), 368–384 (2004).

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L. & Mayer, D. M. Why employees do bad things: moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Pers. Psychol. 65 (1), 1–48 (2012).

Funding

We did not receive any funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhe Liu was in charge of the framework design, data processing, and manuscript writing; Yijun Dong was tasked with questionnaire design and data collection. All authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before data collection, the study underwent review and approval by the Ethics Committee of the School of Business Administration at Henan University of Animal Husbandry and Economy (Approval No. EA2024029). The review confirmed that the study utilized anonymized interview data, safeguarded participants from harm, and did not involve experiments on humans or the use of human tissue samples. Additionally, the study did not infringe upon sensitive personal information or commercial interests. It adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. Furthermore, in accordance with relevant legislation, all participants were adults, as the legal working age exceeds the age of majority. All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Dong, Y. Unveiling the formation mechanism of workplace deviance among front-line star nurses. Sci Rep 15, 43063 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27135-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27135-1