Abstract

Ecosystem services (ES) provision and variation over spatial scales in agricultural land are often the result of interactions between agricultural management and ecological structures. Our goal was to evaluate the effect of conservation agriculture (CA) and conventional tillage (CT) practices on different ES and ecosystem disservices (DES) to evaluate their spatial variability, and to develop a new index to determine the sustainability of CA and CT systems in farmers’ fields. Under conservation agriculture and conventional tillage, the ecosystem services supplied by wheat-based cropping systems was measured, and the inverse distance weighted (IDW) interpolation technique was used to create maps of spatial variability. A new index, i.e., ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI) was developed to assess the sustainability of the study area. The gain in food was higher in some parts of the Nilokheri and Taraori villages of Karnal district, where CA was practiced over the years. The gain in regulating service, i.e., SOC stock in the study area ranged between 1.99 and 5.54 Mg ha–1. The study revealed approximately 178% increase in supporting service, i.e., soil formation in Nilokheri block over the study area. The ESSI of Karnal ranged between 1.48 and 7.60, and for Kaithal district it was between 1.22 and 6.24. In the study area, 67 villages were reported as degraded, 28 villages as vulnerable, 38 villages as sustainable but input intensive, 17 villages as sustainable. By incorporating ecosystem service concepts into conservation agriculture, wheat agroecosystems can be transformed into more robust and sustainable production systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Farming is the largest constructed ecosystem and is highly dependent on ecosystem services from the natural environment, as agricultural ecosystems make up around 40% of the Earth’s terrestrial area1. Over the past few decades, land use change has accelerated, particularly land conversions2. Growing grasslands and natural landscapes have been converted into agricultural land uses3. According to estimates, more than 40% of the terrestrial ecosystems on the earth are currently managed for agricultural purposes4. These adjustments and shifts were made to increase food production at the price of a decline in the performance of ES5,6. The ES idea explicitly states that human well-being is spatially and temporally dependent on ecosystems7,8 and can be compared to the products and services that well-operating ecosystems deliver9. Specifically, agroecosystems from different management systems provide significant ES to social well-being. Agriculture contributes to food security, improving livelihood, and reducing poverty10. Agricultural ecosystem services provide people with health, livelihood, survival, and sustain life on earth. Most of the ecosystem services agriculture provides are supplied through the soil11. Soil properties, type, and variation in fertility play an essential role in determining whether farming can take place or not and what the quality of the product will be. It also influences the productivity of that crop12. Soil fauna, i.e., earthworms, microorganisms, micro-invertebrates help to improve soil properties like structure, fertility, organic matter content, and crop production13. Soil microbes (bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, etc.) improve soil fertility by inducing organic matter decomposition and nutrient recycling14. However, some agricultural practices can decrease ES delivery, mainly due to years of soil erosion15, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions16, intensive soil disturbance with tillage16, and continuous removal of nutrients through the harvest of products.

Traditional farming practices, such as intensive tillage and flood irrigation for wheat demand significant amounts of nitrogen fertilizers, water, and machinery. These methods contribute to approximately 13–21% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with agriculture being a major source of nitrous oxide and methane17. In addition, the overuse of nitrogen fertilizers has led to nitrate pollution, with nearly 20% of groundwater samples in India exceeding safe nitrate levels18. Groundwater levels have also been severely impacted, with excessive irrigation practices depleting this vital resource18.

The environmental toll is evident in the degradation of ecosystems, reduced biodiversity, and water pollution. There is an urgent need for sustainable agricultural approaches, including conservation agriculture and balanced nutrient management to lessen these effects and guarantee long-term food security19. So, there should be an alternative way of sustainable farming to restore ES and achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). In this case, the main challenge is creating a replacement production system that can help sustain crop yields in the long run and is resilient to climate, resources, and ecosystems.

To maintain soil health in the long run, sustainable use of natural resources is the only way that can be achieved through CA. For sustainable crop intensification, conservation agriculture has been promoted as a system of agronomic practices that includes crop rotations, including cover crops, permanent organic soil cover by retaining crop residues (at least 30%), and reduced tillage (RT) or no-till (NT)20,21. Together, these practices aim to improve crop productivity by enhancing a number of supplying, regulating, and supporting ecosystem services16. Compared to traditional agriculture, CA improves soil properties and processes, which impacts the supply of ecosystem services, such as regulation and provision of water along with climate regulation through carbon sequestration and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG’s) emissions.

The assessment and measurement of ES in natural ecosystems and landscapes have been the subject of numerous studies. But there are very few reports and/or research available on the evaluation of ES at agroecosystems scale worldwide. A novel approach was applied across six villages in two regions of Burkina Faso, West Africa, revealing that ecosystem service (ES) provision becomes increasingly vital in subsistence farming systems, especially during years of poor crop performance22. Ericksen et al.23 assessed ES in semi-arid and arid regions of Northern Kenya, showing how land use and geography influence service provision and its market value. To evaluate trade-offs and synergies among the various services offered by major agroecosystems, reduce their environmental footprint, and identify and map key ecosystem areas. Moushani et al.24 updated the MEA report for the soybean agroecosystem. They quantified and mapped different ecosystem services and disservices in conservation and conventional farming fields in the Golestan Province (north of Iran), and results showed that conservation cropping systems in general provided better-performing ES than conventional cropping systems.

ES maps are essential tools for decision-makers and institutions, allowing them to spatially identify areas that should be preserved due to their high supply of ecosystem services25. The mapping of specific ES involves various methods and models, each with its approach and benefits, which can be interesting and engaging for the audience26. The indicators measuring ecosystem services vary significantly among provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services. Geospatial data plays a crucial role in determining the spatial extent of these services. Additionally, linking this data to assessment rankings facilitates smooth and efficient map generation27. In order to describe the service-providing units both visually and mathematically, a geospatial information system is crucial28. The maps, a product of these systems, play a pivotal role in assessing spatial trade-offs among ecosystem services and has a vital step in prioritizing areas of concern for sustainable agriculture. By mapping these services, we gain a deeper understanding of their dynamics, which in turn helps us identify degrading services and make informed decisions for the sustainable use of natural resources. Mapping of ES in the farmers’ fields where they have been practicing CA for a long time and assessing the sustainability of the area with the help of a newly developed index is very rare in the available literature. So, the objective of the study was to assess the effect of CA practices on different ES and DES; evaluate CA’s spatial variability, and develop a new index to determine the sustainability of the CA and CT system in farmers’ fields. The outcome of the study would help the policy makers to formulate the payment scheme for ES along with recognising the potential of CA practices in fulfilling SDGs.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was carried out in the Karnal and Kaithal districts of Haryana, located in northern India (Fig. 1). A spatial map of the study area was prepared to delineate the geographic boundaries of Karnal and Kaithal districts in Haryana with soil-sampling points collected under conservation and conventional tillage conditions. Taluk-level administrative shapefiles were downloaded from the Survey of India digital repository (Survey of India: https://onlinemaps.surveyofindia.gov.in/Digital_Product_Show.aspx), and imported into a ArcGIS environment, projected to UTM (WGS-84) coordinate system for consistency. Point coordinates corresponding to sampled farmers’ fields were georeferenced and overlaid on the district polygons, and cartographic elements were added to enhance interpretability. This area is regarded as a developing centre for agricultural growth. The study’s primary focus was on land use associated with wheat cultivation, although other crops such as rice, maize, and mustard are also commonly grown. Because of recent government initiatives to promote sustainable agricultural practices in the region, such as the adoption of conservation agriculture systems for both rice and wheat farming, wheat was chosen as the focal point.

The climate of Karnal and Kaithal districts is dry, featuring hot summers and cold winters. The cold season runs from mid-November to mid-March, while the hot season lasts until June. This region has a subtropical, semi-arid to subhumid continental climate with extreme summer heat and winter cold with significant temperature fluctuations and low humidity for most of the year. The average annual rainfall is 744 mm over 31 to 35 days, with about 82.4% occurring due to southwest monsoon. The average summer temperature is 34–39 °C, while winter temperature ranges from 6 to 7 °C (Fig. 2).

The soils found in Karnal and Kaithal districts are part of the extensive Indo-Gangetic alluvial plain. Further the Karnal region is divided into three sub-micro zones: the Assandh Plain, Karnal Bhangar, and Yamuna Khadar. Soil in this region is dominantly alluvial in origin, with surface textures ranging from loamy sand to sandy loam. While in Kaithal, the terrain is shaped by rivers such as the Yamuna, Ghaggar, and Markanda, as well as seasonal streams descending from the Siwalik hills. The area features typical alluvial landscapes associated with Indo-Gangetic plains. The main crops cultivated in these districts include wheat, rice, sugarcane, cotton, and sorghum. The soil classification falls under the Entisol order, specifically fluvents suborder and ustifluvents great group.

Soil sample and data

A stratified random sampling technique was used to select the blocks, gram panchayat, and study units (households) for primary survey. Six blocks of Karnal (Karnal, Nilokheri, Nisang, Gharaunda, Assandh, and Indri), and seven blocks of Kaithal (Kaithal, Pundri, Kalayat, Siwan, Rajound, Alewa, and Pillukhera) were selected at first level. Total of 150 farm fields in the villages of above-mentioned blocks were monitored and visited regularly during wheat growing season. The farmers were interviewed for collection of data regarding method of cultivation, cropping history, variety used, yield, irrigation water (source and depth), and the fertilizers applied (amount and type). During the survey, it was noticed that areas of practicing conservation agriculture (CA) varied in different villages. Therefore, 60 villages across two districts where both CA and CT practices were taken for a comparison study. A total 120 soil samples (0–15 cm) were collected from both CA and CT fields from the available villages during the wheat growing season (2021–22 and 2022–23), and another 30 samples were taken from the CT. Altogether, 150 soil samples were collected from the study area. The location of points from where soil samples were collected is given in Fig. 1.

Evaluation and quantification of ES

In this study, a new framework was developed for mapping of ES based on the modified Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Gain and straw yield were considered as provisioning services, available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, and water holding service are categorised under regulating services, and soil formation and soil fertility were considered under supporting services. For each of the provisioning, regulating, and supporting services we developed a quantitative system consisting field methods, laboratory experiments, questionnaire survey, and spatial analysis (Fig. 3). For all ecosystem services we sampled, analyzed, and evaluated gain in services under conservation practices over the conventional according to the following procedures.

Provisioning services

Grain and straw production make up the majority of provisioning services in wheat fields. Agroecosystems’ diverse ecosystem services (ES) produce these outputs. Samples were taken from 1.0 × 1.0 m (1m2) plots in April of 2022 and 2023 to estimate wheat yield and biomass. Following harvesting, the plant material was oven-dried for 48 h at 70 °C. The dry biomass (oven dried) was then weighed to find the dry matter content.

Regulating services

Soil organic carbon and carbon stock

The organic carbon content in soil was assessed using Walkley and Black29 wet oxidation method. To convert the oxidizable organic carbon to total soil organic carbon (SOC), a correction factor of 1.32 was applied30, ensuring improved accuracy in the estimation. The SOC stock (in Mg ha⁻1) at 0–15 cm soil depth was then computed based on equation proposed by Lal31:

where, SOCconc denotes the concentration of organic carbon expressed in kg C Mg⁻1 of soil; T is the depth of the soil layer (in meters); and BD refers to the soil bulk density (Mg m⁻3).

An improved technique utilizing an "equivalent soil mass" approach was used to account for changes in bulk density brought on by experimental treatments. To avoid bias resulting from treatment-induced BD differences (Mg m−3), the ‘equivalent depth basis’ correction (i.e., additional thickness (Tadd, m)) was calculated from the differences between soil mass and the equivalent soil mass and subsurface BD32, and was added to the formula. The updated formula incorporating this correction is:

Available soil nutrient content

Subbiah and Asija’s alkaline permanganate method33 was used to measure the amount of available N in the soil. Available P was estimated following the sodium bicarbonate extraction method described by Olsen et al.34. For the assessment of available K, method proposed by Hanway35 was employed. This technique measures exchangeable and water-soluble potassium, excluding potassium present in saline or saline-sodic soils.

Water holding services

Water holding services (WHS) of soil was calculated based on gravimetric water content and bulk density of soil. WHS was calculated using the following formula Eq. 3

O2 supply

The photosynthetic process, in which plants transform atmospheric carbon dioxide into organic matter, is principally responsible for generation of oxygen in wheat fields. About 1.2 kg of oxygen is released as a byproduct of the process, which involves the assimilation of 1.63 kg of carbon to create 1 kg of plant dry matter per ha. Consequently, the following relationship (Eq. 4) can be used to estimate the oxygen supply36,37,38

Water regulation

Two important factors influencing water movement in the soil were found to be saturated hydraulic conductivity and total porosity. The constant head permeameter method was used to calculate saturated hydraulic conductivity39. Soil bulk density was assessed in its undisturbed state through core auger method, following the approach of Blake and Hartge40. The following formula (Eq. 5) was then used to determine total porosity (%):

where, BD represents the soil’s bulk density PD denotes the particle density, typically assumed to be 2.65 Mg m⁻3 for mineral soils.

Soil microbial respiration

Soil microbial respiration was evaluated as a key indicator of microbial activity following crop harvest. The evaluation was carried out in the lab utilizing Nelson and Sommers’ alkali trapping technique41. The following formula (Eq. 6), which was modified from Schinner et al.42, was used to determine the rate of soil respiration:

where B is the amount of HCl (mL) used in the control procedure; S is the amount of HCl (mL) used to treat the sample; 2.2 = Conversion rate; SW = Soil Weight; N = total days of incubation.

Supporting services

Soil formation

The rate at which soil forms is intricately tied to the presence and activity of earthworms within an ecosystem. This study, assessing the ecosystem’s value concerning soil formation focused on the population density of earthworms in wheat fields. The abundance of earthworms was determined utilizing the Tullgren funnel method43. With an average biomass of 0.2 g per earthworm44, one tonne of earthworms produces one tonne of soil per hectare each year45. Sandhu et al.46 evaluated the soil formation using Eq. (7):

Soil structural stability

The structural stability of soil aggregates was assessed using Mean Weight Diameter (MWD). For this analysis, air-dried soil clods that passed through an 8 mm sieve but retained on a 4 mm sieve were selected. These clods were then subjected to wet sieving using a set of sieves with mesh sizes of 4.0, 2.0, 1.0, 0.50, 0.25, 0.10, and 0.05 mm. The sieving was performed with a Yoder-type wet sieving apparatus, following the method outlined by Kemper and Rosenau47. The following formula (Eq. 8) was used to determine the MWD:

where ‘Wi’ is the fraction of the total sample weight retained on each sieve, and ‘Di’ is the average diameter (mm) of the aggregates within each size class.

Soil fertility

Soil fertility was evaluated by determining the soil’s role in supplying nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) to crops, based on their uptake in typical soils, following the methodology of Roy et al.48. To estimate nutrient uptake per unit of crop yield, the total uptake from both soil and fertilizer sources was considered. The nutrient contribution from fertilizers was calculated using standard nutrient use efficiency (NUE) values for wheat in the Indo-Gangetic Plains (IGP), with efficiencies assumed at 30% for nitrogen (N), 25% for phosphorus (P₂O₅), and 50% for potassium (K₂O), as reported by Ravichandran and Sriramachandrasekharan49, Vinod and Heuer50, and Lakshmi et al.51. The soil’s contribution to nutrient uptake was then estimated by deducting the fertilizer-derived nutrient share from the total nutrient uptake, following the approach described by Mandal et al.16.

Spatial mapping of ES

Spatial variability map of soil physical parameters and gain in ecosystem services in Karnal and Kaithal districts was generated through inverse distance weightage (IDW) method and ArcGIS 10.7.1 was used. The schematic diagram of the process of generation of thematic maps is given in Fig. 3.

Inverse distance weighted (IDW) interpolation operates on the assumption that closer things are more like each other than those farther apart. To estimate a value for any unmeasured location, IDW utilizes the measured values surrounding that location. The values nearest to the prediction location exert more influence on the estimated value compared to those farther away. Each measured point was considered to have a local influence that diminishes with distance. This method assigns greater weights to points closest to the prediction location, with the influence decreasing as distance increases. (Eq. 9)

where,

Zp = estimated value z of a unsampled point as a function of the z-values of the nearest n points.

di = distance between the unsampled point and measured point.

n = no of nearest measured points used for interpolation.

Development of ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI)

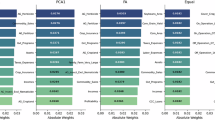

In order to assess the sustainability of agroecosystem, our study quantified the ecosystem service from wheat-based agroecosystem. After performing multiple linear regression and stepwise regression, the most significant services were selected for the development of a new index called ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI). Nine ecosystem services based on the present study were selected for the development of ESSI (Table 1).

Observed values (i.e., range obtained from the study area) of these nine services were again classified in five classes (1–5) in regular class intervals. Each class was given a score (the score is the same as the class number). Ecosystem services were classified as ‘higher is better’ meaning the highest value was given as class 5 and the lowest value as class 1. The score of each service (according to the class) was multiplied by the observed value of ES for that class. The multiplied values were summed up and again divided by 1000 to make the index value in a 0–10 scale (Eq. 10)

where,

\({\text{X}}_{\text{i}}\) = Class parameter

Wi = Class Score

Statistical analysis and software used

Statistical analysis was carried out using the “agricolae” package in as RStudio (Posit team, 2024) as described by de Mendiburu52. To determine significant differences between treatment means, Tukey’s post hoc test and the Least Significant Difference (LSD) method were applied at a 5% level of significance (α = 0.05). All spatial datasets were georeferenced using the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM)coordinate system based on the WGS-84 datum. Spatial distribution patterns of ecosystem services (ES) were interpolated using ArcGIS 10.7.1. The choice of interpolation technique was guided by the underlying data distribution and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Geostatistical modelling i.e., Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation was conducted in ArcGIS 10.7.1 using the Geostatistical Analyst tools available in ArcMap 10.7.1.

Result and discussion

Spatial variability maps of different soil ecosystem services

To detect the spatial variability of soil bulk density (Mg m–3) and porosity (%) in the study area, maps were generated through Inverse Distance Weighted for Karnal and Kaithal districts (Fig. 4).

The bulk density (BD) of the study area ranged between 1.34 and 1.77 Mg m–3 and was classified into six classes, as shown in the map (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the porosity of the study area varied between 33 and 49% (Fig. 4b). The spatial variability map of BD and porosity for the study area revealed that the eastern part of the study area, i.e., Nilokheri blocks, and some parts of the Karnal district had the lowest BD and the highest porosity. On the other hand, the areas where CT was practiced, i.e., some parts of Assandh, Gharaunda, Alewa, and Kalayat, had higher BD and lower porosity values. Results revealed that mean weight diameter (MWD) of the whole study area ranged between 0.25 and 1.38 mm (Fig. 5a) and hydraulic conductivity varied between 3.05 and 9.74 cm hr–1 (Fig. 5b). The spatial variability map of the study region showed that the villages under the Nilokheri region, some parts of Karnal, and a few villages of Siwan had less BD, high soil organic carbon, higher hydraulic conductivity (HC), and higher available N, P, K as those regions were under CA based cultivation for last 9 years53.

An interpolated map of soil organic carbon (%) (Fig. 6a) and SOC stock (Fig. 6b) of the study region showed that the SOC values ranged between 0.43 and 0.93% and SOC stock varied between 8.38 and 20.81 Mg hr–1. The spatial variability map of SOC and SOC stock revealed that the Karnal and Nilokheri block of the Karnal district had high SOC content. Similarly, for SOC stock, the Nilokheri region and Karnal block showed comparatively higher SOC stock over other regions. The spatial variability map of soil available N, P, and K in the study area (Fig. 7) showed that in Nilokheri and some parts of the Karnal district where CA followed, the higher value of available N, P, and K was found. The nitrogen content available in the soil varied between 106.7 and 234.0 kg ha–1, being more abundant in Nilokheri compared to other areas (Fig. 7a). In a similar way, the phosphorus present in the soil ranged from 15.3 to 33.2 kg ha–1, with concentrations of available soil P being higher in the Nilokheri region (Fig. 7b).

The available potassium in the soil ranged from 183.9 to 204.6 kg ha–1 across the study area (Fig. 7c). The eastern part of the study area, especially in Nilokheri and Karnal block of Karnal district, showed significantly high soil available N, P, K over other regions where CT was primarily followed. The regions where CA was practiced had improved soil physical structure, and improved or gained ecosystem service over CT was also higher. CA-based farming in the Nilokheri region had a significant gain in provisioning service over other areas as CA leads to higher grain and by-product yield. Improved SOC, soil respiration, and available N, P, and K directly influence the yield in that region53. Palm et al.54 and Adak et al.55 reported that conservation agriculture systems improve soil properties and processes, such as organic matter and organic carbon, while also reducing erosion and runoff and improving water quality, soil quality, and biotic production capacity. According to Auerswald et al.56, organic matter has a direct impact on soil erosivity and an indirect impact on the integrity of soil structure. Chen et al.57 found that in wheat monoculture on China’s Loess Plateau, conservation and decreased tillage techniques increased soil organic matter and total nitrogen. Conservation methods increase microbial respiration because they keep crop leftovers on the ground, increase soil moisture rates, and make nutrients available to soil microorganisms.

Soil respiration in the examined area ranged from 25.81 to 42.43 mg CO2 kg–1 soil day–1 (Fig. 8). The interpolated soil respiration map for the study area revealed that the Karnal block, the Nilokheri region, and several villages in Kaithal, particularly in the Siwan district, exhibited higher soil respiration rates than other CT-based regions.

Austin et al.58 determined that microbial biomass and respiration are critical characteristics and indicators of soil development and processes such as the global carbon cycle, nutrient cycles, and biological enhancement. The current study generated a microbial respiration map utilizing the interpolation technique within an ArcGIS 10.7.1 framework. This map indicates that villages in the Nilokheri region demonstrate elevated levels of microbial respiration. This finding suggests that the type of cropping systems employed can influence soil microbial respiration, resulting in higher rates in conservation fields.

Improvement in ES under CA practices

Improvement in provisioning ES under CA over CT

The gain in provisioning ecosystem services in CA over CT was analysed at the regional scale using IDW interpolation technique of ArcGIS 10.7.1 software (Fig. 9). Gain in food (wheat yield) in the entire study area ranged between 0.55 and 0.77 t ha–1 with a mean of 0.63 t ha–1 (Fig. 9a). The gain in food was recorded higher in some parts of the Nilokheri and Taraori village of Karnal district where CA was practiced over the years. The result indicated ⁓ 42% increase in food (grain yield) in the Nilokheri region over the area. Similarly, in the case of by-product, the gain in by-product value in CA over CT of the study area ranged between 0.85 and 1.10 t ha–1 where the average gain in by-product was reported as 1.06 t ha–1 (Fig. 9b).

The highest gain in by-product value was observed in the eastern part of the study area, i.e., the Nilokheri block of Karnal district where whereas the lowest was observed in Kaithal district. In the Nilokheri region, the villages where CA was practiced for a long period had shown a 38% increase in by-product value over the regions where the gain in byproduct was lowest. The spatial variability map of gain in food and by-product in the study area, showed the highest gain in the areas where CA was practiced for a longer period.

Improvement in regulating ES under CA over CT

The gain in regulating ecosystem services under CA compared to CT was analyzed on a regional scale using IDW interpolation techniques of ArcGIS 10.7.1 software (Fig. 10). The gain in SOC stock in the study area ranged between 1.99 and 5.54 Mg ha–1 with an average of 5.22 Mg ha–1 (Fig. 10a). The gain in SOC stock was recorded higher in some parts of Nilokheri and Taraori village of Karnal district where CA was practiced over a long period of time. The study reported ⁓ 9.1% increase in the gain of SOC stock in the Nilokheri region over the area where the lowest gain in SOC stock was observed.

Similarly, in the case of soil available nitrogen, the gain in CA over CT of the study area ranged from 64.7 to 85.7 kg ha–1 where the average gain was reported as 73.2 kg ha–1 (Fig. 10b). The highest gain in available N was observed in the eastern part of the study area, i.e., Nilokheri block of Karnal district whereas the lowest was observed in Kaithal district. In the Nilokheri block, the villages where CA was practiced for long period of time had shown a 31% increase in gain of soil available N over the regions where the gain in soil available N was the lowest. The spatial variability map of improvement in soil available P of the study region showed highest gain in areas where CA was practiced for a long while. Gain in the soil available P ranged between 7.0 and 11.7 kg ha–1 over the study region whereas the average gain in soil available P was 9.2 kg ha–1 (Fig. 10c). The highest gain in the soil available P was recorded in the Nilokheri and some villages of Karnal block and the lowest was in Kaithal and Siwan block and some parts of Assandh. The study showed that the gain in the soil available P was approximately 33% higher in the Nilokheri block over the regions where the gain in soil available P was the lowest. Spatial variability map of improvement in soil available K of the study region showed that the eastern region of the study area was higher in terms of gain in soil available K. There was approximately 28.1% increase in gain in Nilokheri region over where the lowest gain in soil available K was observed. The gain in soil available K over the study area was ranged between 55.9 and 87.1 kg ha–1 with an average value of 71.1 kg ha–1 (Fig. 10d). Those maps revealed regions where CA was practiced for almost 9–10 years provide the highest gain in regulating services. This is likely due to higher concentrations of available soil nutrients such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) observed in these areas. Previous studies have indicated that CA enhances soil fertility and boosts nutrient availability59,60. Compared to conventional tillage (CT), CA practices tend to increase the surface concentration of N, P, and K59. In the Nilokheri region of Karnal, for instance, supporting services, particularly those related to soil fertility (N, P, K contributions), showed significant improvement under CA. This can be attributed in part to residue retention, which reduces nutrient losses by slowing nitrogen mineralization61,62. The elevated phosphorus levels observed in residue-retained plots may result from organic acids released during organic matter decomposition, which enhance the solubilization of native phosphorus reserves63,64. Additionally, the increased availability of potassium in CA-managed soils may stem from the substantial potassium input via cereal crop residues, which are rich in total K and can rapidly convert to plant-available forms65. These findings are consistent with earlier research by Jat et al.66 and Malecka et al.67.

Spatial variability map of study area revealed that the gain in water holding service (WHS) was higher in Nilokheri region of Karnal and some part of Kaithal block. Gain in WHS was ranged between 86.8 and 332.9 m3 ha–1 with an average of 171.8 m3 ha–1 for the whole study region (Fig. 10e). It was observed that the highest gain in water holding services (WHS) was in Nilokheri region as the farmers practices CA from very long time. The lowest gain in WHS was observed in Kalayat and Rjound area of Kaithal district. Soil water holding capacity (WHC), the total amount of water retained in the soil after excess has drained is more than a technical measurement; it plays a critical role in supporting crop productivity and mitigating the impacts of climate variability. Enhancing WHC strengthens soil resilience, improving the agroecosystem’s ability to withstand extreme weather events68. Increased soil WHC is not just a number, it is a shield, associated with higher infiltration rates and lower runoff. Also, it is a powerful tool demonstrating decreased potential of soil erosion, especially during intense rain events69. On the other hand, soils with low WHC often suffer from inefficient water use due to excessive percolation, which can result in nutrient leaching, environmental degradation, and reduced economic returns70,71,72. Adoption of conservation agriculture has shown promise in this regard. Practices associated with CA can enhance soil organic matter and improve pore size distribution, contributing to increased WHC73. The spatial variability map of gain in water holding services in villages where CA was practiced showed the highest gain in the areas of Nilokheri, where most of the CA fields were in existence.

Improvement in supporting ES under CA over CT

The gain in supporting ecosystem services under CA compared to CT was analysed on a regional scale using Inverse distance weightage (IDW)interpolation of through ArcGIS 10.7.1 software (Fig. 11). Among the supporting services, the spatial variability map of improvement in soil formation of the study region showed that gain in soil formation ranged between 42.04 and 136.04 kg ha–1 yr–1 in the study region with an average value of 75.63 kg ha–1 yr–1 (Fig. 11a). The study revealed that there was approximately 178% increase in gain in soil formation in the Nilokheri district over the region’s lowest gain was observed. The gain in soil formation over the study region was the lowest in the Siwan, Kalayat, and Kaithal blocks of Kaithal district.

Soil fertility is the ability of soil to contribute major nutrients (N, P, and K) to the plant. Result indicated that the gain in soil contribution for nitrogen (kg ha–1) in the study region ranged from 45.9 to 54.6 kg ha–1 with a mean value of 49.0 kg ha–1 (Fig. 11b). The spatial variability map of gain in soil contribution of N had shown that gain was higher in the eastern region of the study area (i.e., Nilokheri region and some parts of Kaithal district). The gain in soil contribution of phosphorus in the study region varied from 11.8 to 14.7 kg ha–1 with the mean value of 13.0 kg ha–1 (Fig. 11c). Spatial variability of the soil contribution of P showed an improvement in the Nilokheri region of Karnal over all other region of the study. Similarly, the spatial variability map of the soil contribution of K showed a significant gain in Nilokheri and some parts of Siwan where CA was practiced for a long period of time. Soil contribution to K ranged between 23.4 and 33.6 kg ha–1 with an average of 27.5 kg ha–1 (Fig. 11d). The contribution of soil K showed up to 26% higher gain in Nilokheri over the area where gain was lowest. CA-based management techniques may have a direct or indirect positive impact on the soil’s WHS because of its hydrophilic qualities and indirectly by changing the particle size distribution (PSD) and soil pore connectivity by boosting SOM74. So, conservation agriculture and its components have been associated with many benefits, including carbon (C) stored in the soil75, improved soil quality76, decreased runoff and soil erosion77, increasing water productivity78, energy use efficiency79, and higher yield and profitability80.

Development of ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI)

To assess the sustainability of the agroecosystem, the study quantified the ecosystem service from the wheat-based agroecosystem. After performing multiple linear regression and stepwise regression, the most significant services were selected for the development of the Ecosystem Service Sustainability Index (ESSI). The steps for the development of ESSI are given in Section "Development of ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI)". Ecosystem Service Sustainability Index was reclassified in five class and the 0–2 of ESSI was interpreted as “degraded”, 2–4 was interpreted as “vulnerable”, 4–6 of ESSI as “sustainable but input intensive”, 6–8 as “sustainable” and 8–10 as “hot spot” region (Table 2). Result indicated that ESSI of Karnal and Kaithal was ranged between 1.48 and 7.60 and 1.22 to 6.24, respectively (Fig. 12). For the whole study area in Karnal and Kaithal district, 67 villages were reported as “degraded”, 28 villages as “vulnerable”, 38 villages as "sustainable but input intensive", 17 villages as “sustainable”. The spatial variability map of ESSI for the whole study region showed that ESSI varied between 1.22 and 7.6 (Fig. 12). Villages of Nilokheri and Karnal block, and some portion of Siwan and Kaithal were in the “sustainable” category, as mostly CA-based farming was practiced. Villages under Assandh, Pillukhera and Indri ESSI were in the “degraded” category. These findings have practical implications for the long-term sustainability of CA-based farming in these areas. Bhattacharya et al.53 conducted a comprehensive study on the Nilokheri block of Karnal, Haryana, where farmers have been implementing conservation agriculture practices for the past nine years. Importantly, our study aligns with the results reported by Leh et al.81, providing further validation to our findings. As Leh et al.81 also proposed the ecosystem service status index, a tool used to evaluate the overall health of the ecosystem in a typical small dairy farm and its watershed in Benton County, Arkansas. This index, which measured ecosystem service change on a scale from -1 to + 1, with + 1 indicating improved service delivery, was instrumental in our study. This innovative approach to farming prioritizes sustainable practices that protect soil health, and the study revealed marked improvements in both the physical and biological properties of the soil when compared to traditional conventional tillage methods. Specifically, we measured key changes in several soil characteristics, finding that the bulk density had decreased significantly, indicating a lighter soil that can better support plant growth. Additionally, there was a notable increase in soil porosity, which enhance the soil’s ability to retain water and provide aeration to plant roots. Improved soil aggregation was also reported, leading to a more stable soil structure that can resist erosion and compaction. On the other hand, residue retention in CA lead to enhanced soil microbial activity, soil organic carbon, and available nutrients82. Our findings placed the Nilokheri region firmly within the “sustainable” category, reflecting the long-term benefits of CA not only for crop yields but also for environmental health. Our study proofed that managing agro-ecosystems for sustainably improved productivity, better profits, and food security, while safeguarding the environment and improving natural resources which are the hallmarks of CA system13,53.

Conclusion

The findings indicate that conservation agriculture-based farming systems offer higher ecosystem services over traditional cropping systems in the wheat-based agroecosystems of northern India. Further our study demonstrated that conservation systems benefits the agriculture and surrounding ecosystem. By improving soil physical health, nutrient availability, water regulation, and biological activity, CA creates more resilient and productive farming systems. The development of the ecosystem service sustainability index (ESSI) further demonstrated its value as a diagnostic tool, enabling spatial assessment of sustainability across villages and highlighting critical areas in the need of intervention. Regions with long-term adoption of CA, such as Nilokheri in Karnal, Haryana consistently exhibited higher ESSI values, improved soil health, and greater provisioning, regulating, and supporting services, and cultural services, underscoring the cumulative benefits of sustained CA adoption. Beyond immediate gains in crop yield and soil fertility, CA contributes to broader environmental goals, including carbon sequestration, groundwater conservation, and mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, we recommend that this research should be expanded to include additional crops and cropping systems. This research underscores the significant positive impact of adopting conservation practices on soil quality and sustainability, suggesting that such methods could be vital for future agricultural practices in similar regions. Based on our research, we recommend switching from standard cropping to conservation systems to increase the ongoing supply of various ES and safeguard the environment.

Limitation of the study

A careful attention is needed on the sampling scheme, and the intrinsic variability of diverse soil characteristics is essential while merging numerous soil ecosystem services as one synthetic index. We only estimated ES in this study. As a result, we advise looking into dis-services as well. To include the cultural services in the framework, we need to quantify cultural services in a very rigorous way. Lastly, to improve comparability across regions, nations, and management systems, ES assessment in agroecosystems should adhere to internationally recognized frameworks like TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity), IPBES (The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and ES), and CICES (Common International Classification of ESs). Nevertheless, there is a dearth of information to support a forecast of when conservation systems outperform traditional systems in terms of ES delivery. Thus, we recommend that this research be expanded to include additional crops and cropping systems.

Data availability

As per our Institute Policy we are not supposed to share our data in the public domain but the datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

FAO. The future of food and agriculture – alternative pathways to 2050. (FAO, 2018). http://www.fao.org/3/I8429EN/i8429en.pdf

Xiao, J., Zhang, Y. & Xu, H. Response of ecosystem service values to land use change, 2002–2021. Ecol. Indic. 160, 111947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111947 (2024).

Azadi, H., Barati, A. A., Nazari Nooghabi, S. & Scheffran, J. Climate-related disasters and agricultural land conversion: Towards prevention policies. Clim. Dev. 14(9), 814–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.2008291 (2022).

Stewart-Koster, B. et al. Living within the safe and just Earth system boundaries for blue water. Nat. Sustain. 7(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01247-w (2024).

Foley, J. A. et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 309, 570–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772 (2005).

Logsdon, R. A., Kalcic, M. M., Trybula, E. M., Chaubey, I. & Frankenberger, J. R. Ecosystem services and Indiana agriculture: farmers’ and conservationists’ perceptions. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 11(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2014.998711 (2015).

Fisher, B., Turner, R. K. & Morling, P. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol. Econ. 68, 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.014 (2009).

Hassan, R., Scholes, R., Ash, N., Condition, M. & Group, T. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Series). (Island Press, 2005).

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The new generation of watershed management programmes and projects A resource book for practitioners and local decision-makers based on the findings and recommendations of a FAO review, Rome (2006).

Rasheed, S. et al. Ecosystem valuation and eco-compensation for conservation of traditional paddy ecosystems and varieties in Kerala India. Ecosyst. Serv. 49, 101272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101272 (2021).

Kopittke, P. M., Minasny, B., Pendall, E., Rumpel, C. & McKenna, B. A. Healthy soil for healthy humans and a healthy planet. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2023.2228651 (2024).

Freeman III, A. M., Herriges, J. A. & Kling, C. L. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods. (RFF PRESS, Routledge, 2014). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315780917

Mandal, N., Maity, P. P., Maity, A. & Mukherjee, A. Ecosystem Services from Agriculture: an outlook. Food Sci. Rep. 2 (2021).

Prasad, S. et al. Soil microbiomes for healthy nutrient recycling. In Current Trends in Microbial Biotechnology for Sustainable Agriculture 1–21. (Springer, Singapore, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6949-4_1.

Mishra, P. K., Rai, A., Abdelrahman, K., Rai, S. C. & Tiwari, A. Land degradation, overland flow, soil erosion, and nutrient loss in the Eastern Himalayas India. Land 11(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020179 (2022).

Mandal, N. et al. Long-term conservation agriculture influences ecosystem service in maize-wheat cropping system in the North-Western Indo-Gangetic Plain. J. Agric. Food Res. 19, 101720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101720 (2025).

Chataut, G., Bhatta, B., Joshi, D., Subedi, K. & Kafle, K. Journal of agriculture and food research. J. Agric. Food Res. 11, 100533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100533 (2023).

Singh, B. & Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: an increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04521-8 (2021).

Mrabet, R. Sustainable agriculture for food and nutritional security. In Sustainable agriculture and the environment 25–90. (Academic Press, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90500-8.00013-0

Saad, A. A. et al. Energy auditing of a maize–wheat–greengram cropping system under conventional and conservation agriculture in irrigated north-western Indo-Gangetic Plains. Energy 116, 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.09.115 (2016).

FAO. Conservation Agriculture: Principles, Sustainable Land Management and Ecosystem Services. FAO, Rome http://www.fao.org/ag/ca/CAPublications/CA_Teramo_Kassam_Friedrich.pdf. Accessed 13 October 2023 (2011)

Sinare, H., Gordon, L. J. & Kautsky, E. E. Assessment of ecosystem services and benefits in village landscapes–A case study from Burkina Faso. Ecosyst. Serv. 21, 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.08.004 (2016).

Ericksen, P., De Leeuw, J., Said, M., Silvestri, S. & Zaibet, L. Mapping ecosystem services in the Ewaso Ng’iro catchment. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 8(1–2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2011.651487 (2012).

Moushani, S., Kazemi, H., Klug, H., Asadi, M. E. & Soltani, A. Ecosystem service mapping in soybean agroecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 121, 107061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107061 (2021).

Balvanera, P. et al. Conserving biodiversity and ecosystem services. Science 291, 2047–2047. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.291.5511.2047 (2001).

Maes, J., Egoh, B., Qiu, J., Heiskanen, A. S., Crossman, N. D. & Neale, A. Mapping ecosystem services in national and supra-national policy making. In Mapping Ecosystem Services 295–302. (Pensoft Publishers, Sofia, 2017). https://doi.org/10.3897/ab.e12837

Burkhard, B. & Maes, J. Problematic ecosystem services. In Mapping Ecosystem Services 271–280 (Pensoft Publishers, Sofia, 2017). https://doi.org/10.3897/ab.e12837

Boyd, J. & Banzhaf, S. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecol. Econ. 63, 616–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.01.002 (2007).

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37(1), 29–38 (1934).

Jha, P. et al. Predicting total organic carbon content of soils from Walkley and Black analysis. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 45(6), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2013.874023 (2014).

Lal, R. Conservation tillage for sustainable agriculture: tropical versus temperate environments. Adv. Agron. 42, 86–197 (1998).

Ellert, B. H. & Bettany, J. R. Calculation of organic matter and nutrients stored in soils under contrasting management regimes. Can. J. Soil Sci. 75(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjss95-075 (1995).

Subbiah, B. V. & Asija, G. L. A rapid procedure for the estimation of available nitrogen in soils. (1956).

Olsen, S. R. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate (No. 939). US Department of Agriculture (1954).

Hanway, J. J. Soil analysis methods as used in the Iowa state college soil testing laboratory. Iowa Agric. 57, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2022.2094204 (1952).

Chen, Z. & Zhang, X. Value of ecosystem services in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 45(10), 870–876 (2000).

Li, J. & Ren, Z. Research on the values of CO2 fixation and O2 release by landuse ecosystem in Loess Plateau in Northern Shaanxi Province. Sci. Agric. Sin. 44, 2943–2950 (2011).

Li, J., Ren, Z. & Zhou, Z. Ecosystem services and their values: a case study in the Qinba mountains of China. Ecol. Res. 21, 597–604 (2006).

Klute, A. & Dirksen, C. Hydraulic conductivity and diffusivity: Laboratory methods. In Methods of soil analysis: Part 1 physical and mineralogical methods,Vol. 5, 687–734 (1986). https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.1.2ed.c28

Blake, G.R. & Hartge, K.H. Methods of Soil Analysis. In Part 1. Physical and Mineralogical Methods 363–375. 1986.

Nelson, D.W. & Sommers, L.E., Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of soil analysis. Part 3. Chemical methods. Soil Science Society of America & American Society of Agronomy (eds Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., & Sumner, M.E.) 961–1010 (Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 1996).

Schinner, F., Ohlinger, R., Kandeler, E. & Margesin, R. Methods in soil biology (Springer, 1996).

Southwood, T. R. E. Ecological Methods (Chapman and Hall, 1978).

Fraser, P. M., Williams, P. H. & Haynes, R. J. Earthworm species, population size and biomass under different cropping systems across the Canterbury Plains New Zealand. Appl. Soil Ecol. 3, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0929-1393(95)00062-3 (1996).

Pimentel, D. et al. Environmental and economic costs of soil erosion and conservation benefits. Science 267, 1117–1125 (1995).

Sandhu, H. S., Wratten, S. D., Cullen, R. & Case, B. The future of farming: The value of ecosystem services in conventional and organic arable land. An experimental approach. Ecol. Econ. 64, 835–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.05.007 (2008).

Kemper, W. D. & Rosenau, R. C. Aggregate stability and size distribution. In Methods of soil analysis: Part 1 Physical and mineralogical methods, Vol. 5, 425–442 (1986). https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.1.2ed.c17

Roy, R. N., Finck, A., Blair, G. J. & Tandon, H. L. S. Plant nutrition for food security. A guide for integrated nutrient management. FAO Fertil. Plant Nutr. Bull. 16(368), 201–214 (2006).

Ravichandran, M. & Sriramachandrasekharan, M. V. Optimizing timing of potassium application in productivity enhancement of crops. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 24(1), 75–80 (2011).

Vinod, K. K. & Heuer, S. Approaches towards nitrogen-and phosphorus-efficient rice. AoB Plants 2012, pls028. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/pls028 (2012).

Lakshmi, C. S. R. et al. Nitrogen use efficiency and production efficiency of rice under rice-pulse cropping system with integrated nutrient management. J. Rice Res. 5(1–2), 42–51 (2012).

de Mendiburu, F. agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. 2023.

Bhattacharya, P. et al. Assessment of soil health parameters and application of the sustainability index to fields under conservation agriculture for 3, 6, and 9 years in India. Heliyon 6, e05640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05640 (2020).

Palm, C., Blanco-Canqui, H., DeClerck, F., Gatere, L. & Grace, P. Conservation agriculture and ecosystem services: An overview. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 187, 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.010 (2014).

Adak, S. et al. Impact of contrasting tillage, residue mulch and nitrogen management on soil quality and system productivity under maize-wheat rotation in the north-western Indo-Gangetic Plains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1230207. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1230207 (2023).

Auerswald, K., Kainz, M. & Fiener, P. Soil erosion potential of organic versus conventional farming evaluated by USLE modelling of cropping statistics for agricultural districts in Bavaria. Soil Use Manag. 19, 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2003.tb00320.x (2003).

Chen, H. et al. Effects of 11 years of conservation tillage on soil organic matter fractions in wheat monoculture in Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res. 106(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2009.09.009 (2009).

Austin, A. T. et al. Water pulses and biogeochemical cycles in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Oecologia 141, 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1519-1 (2004).

Zhang, C., Mu, P. & Shang, J. M. Effects of continuous returning corn straw on soil chemical properties, enzyme activities and yield trait. Res. Soils Water Conserv. 25, 92–98 (2018).

Büchi, L., Wendling, M., Amossé, C., Necpalova, M. & Charles, R. Importance of cover crops in alleviating negative effects of reduced soil tillage and promoting soil fertility in a winter wheat cropping system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 256, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.01.005 (2018).

Bohoussou, Y. N. D. et al. Impacts of the components of conservation agriculture on soil organic carbon and total nitrogen storage: a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 842, 156822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156822 (2022).

Jahangir, M. M. R. et al. Carbon and nitrogen accumulation in soils under conservation agriculture practices decreases with nitrogen application rates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 168, 104178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104178 (2021).

Margenot, A. J. et al. Can conservation agriculture improve phosphorus (P) availability in weathered soils? Effects of tillage and residue management on soil P status after 9 years in a Kenyan Oxisol. Soil Tillage Res. 166, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2016.09.003 (2017).

Kumawat, C. et al. Phosphorus forms under crop residue retention and phosphorus fertilization in maize-wheat rotation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 53, 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2021.1993882 (2022).

Ranaivoson, L. et al. Agro-ecological functions of crop residues under conservation agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 37, 1–17 (2017).

Jat, H. S. et al. Assessing soil properties and nutrient availability under conservation agriculture practices in a reclaimed sodic soil in cereal-based systems of North-West India. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 64, 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2017.1359415 (2018).

Malecka, I., Blecharczyk, A., Sawinska, Z. & Dobrzeniecki, T. The effect of various long-term tillage systems on soil properties and spring barley yield. Turk. J. Agric. For. 36, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.3906/tar-1104-20 (2012).

Williams, T. G., Dressler, G., Stratton, A. E. & Müller, B. Ecological and financial strategies provide complementary benefits for smallholder climate resilience: insights from a simulation model. Ecol. Soc. 26(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12207-260214 (2021).

Williams, A. T., Rangel-Buitrago, N., Pranzini, E. & Anfuso, G. The management of coastal erosion. Ocean Coast. Manag. 156, 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.03.022 (2018).

Zekry, M., Nassar, I., Salim, H. & Abdallah, A. The Potential of super absorbent polymers from diaper wastes to enhance water retention properties of the soil. Soil Environ. 39, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.25252/SE/2020/132058 (2020).

Wei, Y. & Durian, D. J. Rain water transport and storage in a model sandy soil with hydrogel particle additives. Eur. Phys. J. E. 37, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1140/epje/i2014-14097-x (2014).

Abdallah, A. et al. The potential of recycling wool residues as an amendment for enhancing the physical and hydraulic properties of a sandy loam soil. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 8, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-019-0283-5 (2019).

Abdallah, A. M. et al. Conservation agriculture effects on soil water holding capacity and water-saving varied with management practices and agroecological conditions: A review. Agronomy 11, 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11091681 (2021).

Hallam, J. & Hodson, M. E. Impact of different earthworm ecotypes on water stable aggregates and soil water holding capacity. Biol. Fertil. Soils 56, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-020-01432-5 (2020).

Wan, D. et al. Effects of long-term fertilization on calcium-associated soil organic carbon: Implications for C sequestration in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 772, 145037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145037 (2021).

Naorem, A. et al. Eight-year impacts of conservation agriculture on soil quality, carbon storage, and carbon emission footprint. Soil Tillage Res. 232, 105748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105748 (2023).

Prats, S. A., Malvar, M. C. & Wagenbrenner, J. W. Compaction and cover effects on runoff and erosion in post-fire salvage logged areas in the Valley Fire California. Hydrol. Process. 35, 13997. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13997 (2021).

Magar, S. T., Timsina, J., Devkota, K. P., Weili, L. & Rajbhandari, N. Conservation agriculture for increasing productivity, profitability and water productivity in rice-wheat system of the Eastern Gangetic Plain. Environ. Chall. 7, 100468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2022.100468 (2022).

Congreves, K. A. et al. Nitrogen use efficiency definitions of today and tomorrow. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 637108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.637108 (2021).

Corbeels, M., Naudin, K., Whitbread, A. M., Kühne, R. & Letourmy, P. Limits of conservation agriculture to overcome low crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Food 1, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0114-x (2020).

Leh, M. D., Matlock, M. D., Cummings, E. C. & Nalley, L. L. Quantifying and mapping multiple ecosystem services change in West Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 165, 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.12.001 (2013).

Mishra, A. K. et al. Conservation agriculture enhances crop productivity and soil carbon fractions in Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 1476292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1476292 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The first author is grateful to ICAR-IARI, New Delhi for providing facility and scholarship for carrying out the research work.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nandita Mandal: Writing—original draft, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. Pragati Pramanik Maity: Writing—review & editing, writing—original draft, supervision, resources, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition, formal analysis, conceptualization. Nilimesh Mridha: Writing—review & editing, formal analysis. Tapas Kumar Das: Writing—review & editing, writing—original draft, resources, investigation, funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Kali Kinkar Bandyopadhyay: Writing—review & editing, resources. Subash N. Pillai: Writing—review & editing, resources. Asim Biswas: Writing—review & editing, resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mandal, N., Maity, P.P., Mridha, N. et al. Conservation agriculture enhances ecosystem services and sustainability of the system over conventional agriculture. Sci Rep 15, 43087 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27164-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27164-w