Abstract

Unoccupied aerial systems (UAS) are becoming a regular tool in agriculture to obtain phenotypic information of plant growth and development. In this study, we collected red, green, and blue (RGB) images using UAS multiple times throughout the growing season from a cotton field experiment conducted in 2016 and 2021. Collected images were processed to obtain digital surface models (DSMs) from which canopy height (CH) measurements were extracted. Crop growth curve was obtained by fitting several non-linear growth functions on the multi-temporal CH measurements. The five-parameter logistic function performed best with highest R2 (0.98) and lowest RMSE (6.41). The first and second order derivative of the five-parameter logistic function was performed to obtain several canopy growth parameters. These parameters were used to evaluate the maturity of cotton genotypes and correlated with yield. The maximum growth rate was correlated with yield (R2 = 0.46 in 2016 and R2 = 0.68 in 2021). Additionally, the time of onset of steady phase was used to rate maturity of the genotypes with 80% accuracy. This study demonstrated an approach to summarize high-resolution multi-temporal data obtained by UAS to better understand crop growth and development with a potential to be used for assessing the maturity of the genotypes, yield estimations, and management decisions of plant growth regulators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is a perennial plant with an indeterminate growth pattern. Therefore, it simultaneously produces both vegetative and reproductive structures1. This unique growth habit allows cotton to adapt to varying environmental conditions and makes its growth more complex to manage. As the fruit load develops, the plant’s carbohydrate and nutrient demands increase in proportion to the number of growing bolls. However, the plant’s ability to supply carbohydrates is limited by canopy light interception. Canopy closure and architecture influence how effectively light penetrates through the canopy, with dense canopies reducing photosynthesis in lower leaves and further constraining carbohydrate supply. When carbohydrate demand exceeds supply, the cotton plant reaches “cutout,” which is typically a stage at five nodes above the uppermost white flower. This stage marks the end of major new node formation and shifts resources toward boll development and maturation2,3. Cutout represents a crucial transition point in cotton growth, directly impacting yield, fiber quality, and overall net returns. The growth pattern of cotton typically follows an S-shaped sigmoidal curve, commonly observed in biological systems. This curve is divided into three phases by days after planting (DAP): the lag phase (10–30 DAP), exponential phase (30–75 DAP), and maturation phase (75–120 DAP)4. The lag phase corresponds to early growth, dominated by seed germination and root establishment. During the exponential phase, rapid biomass accumulation occurs due to canopy expansion and the development of reproductive structures, such as squares and bolls5. The maturation phase, which begins after cutout, is marked by slower growth as the plant focuses on boll maturation and fiber development6.

Nonlinear growth models, such as the Gompertz curve, are widely used to study these dynamics and explain how growth rates change over time7,8,9. This approach has greater adaptability7 and has been employed for a long time to study the complex process of plant growth8. As cotton growth follows an S-shaped sigmoidal pattern, several non-linear models have been developed to describe it10,11. These functions such as three parameter (3P), four parameter logistic (4P), and five parameter (5P) differ in their flexibility12,13. The 3P function assumes a lower asymptote of zero, reaches an inflection point at maximum growth, and eventually converges exponentially7,14. The 4P function relaxes some of these constraints15, but both are limited in handling asymmetric data16. By adding a fifth parameter, the 5P function captures curve asymmetry and provides greater modeling flexibility17,18. This factor significantly reduces the lack-of-fit error19. For example, in cotton, the shift from vegetative to reproductive growth involves complex physiological changes that may not align with the rigid phases defined by simpler models2. Similarly, incorporating additional inflection points allows for a more precise estimation of growth phase timing and duration which can improve the effectiveness of assessing agronomic treatments such as irrigation, fertilization, use of growth regulators20, and evaluate genotypes for their response to the environment. Using a sigmoidal curve with five inflection points offers an opportunity to capture them and allow for more detailed growth phase analysis. This approach could improve predictions of phase timing, duration, and growth rate by addressing key limitations in current modeling techniques. These enhanced modeling approaches must be supported by accurate and high-frequency monitoring to capture the nuances of crop growth. Effective crop growth monitoring can be done by using the structural phenotypic features of the plants21. One such phenotypic feature, canopy height (CH), reflects the structural properties of the cotton canopy22 and can be used to study the growth process. Accurate growth analysis requires high-frequency data collection throughout the growing season to extract reliable parameters, which can then be used to assess the impact of biotic and abiotic stresses, cultivar maturity, and yield estimations23,24. Although some studies have investigated the rate and timing of growth, routine use in crop research remains limited. Manual data collection several times over the season is time-consuming, laborious, and often prone to errors25,26. Recent advancements in unoccupied aerial systems (UAS) technology offer a solution to these challenges27. Equipped with diverse sensors, such as RGB and multispectral cameras, UAS platforms can collect high-resolution, spatiotemporal data that can accurately assess plant growth dynamics, including CH, canopy cover, and canopy volume28,29,30. These measurements provide an understanding of growth patterns and health status over time. Moreover, UAS data enables the integration of vegetative indices such as NDVI and allows precise tracking of canopy health and maturity progression31,32. This approach has the potential to refine harvest-aid application timing and rates by incorporating spatial variability and reducing costs and environmental impact.

While UAS enables the collection of large amounts of data, these datasets are often underutilized. Studies primarily focus on basic applications, such as detecting phenotypic features, estimating yield or measuring instantaneous growth parameters, without analyzing how these features evolve over time33,34,35. Based on these studies, this underutilization arises from a lack of advanced modeling tools and standardized workflows to integrate and interpret high-dimensional, multi-temporal UAS data. This lack of tools and workflows prohibit machine learning and time-series analysis to unlock dynamic crop growth analysis. This creates a scenario where important temporal information remains untapped and limits the potential for overall crop growth analysis. For example, while CH measurements are routinely extracted from UAS data, their integration into growth models for phase-specific analysis or yield estimation is rarely explored22. To address this, our study proposes using UAS-derived multi-temporal datasets to develop growth curves and extract growth parameters.

The novelty of this study was to demonstrate the adaptation and integration of growth functions on UAS-derived CH and derive growth parameters that can be potentially used to assess genotypes in breeding programs. Additionally, we hope that these growth parameters can be used by agronomists to optimize irrigation timing and plant growth regulators. A web-based user interface was developed to perform growth analysis using UAS-based canopy features such as CH and to extract growth parameters proposed in this study. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to propose a crop growth analysis tool that can summarize multi-temporal data sets collected by UAS and can obtain parameters to quantify the timing, rate, and length of major crop growth phases with use cases for evaluating cotton maturity and yield estimations36. Hence, this study aimed to (i) perform growth analysis by using CH measurements obtained from UAS, (ii) extract growth parameters from CH, and (iii) assess the relationship between the yield of cotton varieties and the growth parameters obtained from CH.

Materials and methods

Experimental set-up

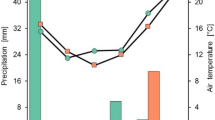

This study was conducted at Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Corpus Christi (27.780834 N, 97.561389W) in 2016 and 2021. The soil in the research field is classified as Victoria clay [fine smectic hyperthermic Sodic Haplusterts Vertisol (Soil Series Classification Database, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 2014)]. The weather data from 2016 and 2021 (Fig. 1) were collected from a local weather station (Campbell scientific: HMP60-L10 Vaisala Temperature and RH Sensor, and TE525-L25 6″ Orifice Rain Gauge) located at the experimental site. The year 2021 was wet and the average maximum temperature from planting to harvest was 36.6 °C and received a cumulative rainfall of 620 mm. In 2016, the cotton growing season was relatively dry with cumulative rainfall of 295 mm and the average maximum temperature was 38.3 °C. Our aim in selecting two years with contrasting weather was to investigate if CH differences and subsequent variations in growth rates due to weather would create any differences in growth analysis and parameters.

Trial establishment

Thirty varieties in 2016 and forty-two varieties in 2021 were planted in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with four replications under rainfed cropping system. Each plot consists of two rows, 10 m long, and 96 cm spacing. In both years, seeds were planted using a two-row cone planter at seeding rate of 12 seeds/meter. Planting was done on April 1st in 2016 and March 26, 2021. Plots were machine harvested with a modified John Deere 9930 spindle picker on August 9, 2016 and August 24, 2021.

UAS data collection and processing

DJI Phantom 2 Vision Plus (2016) and DJI Phantom 4 RTK (2021) (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) was used as the UAS platforms to collect images. Phantom 2 is equipped with a 1/2.3′′ 14 Mega pixels (4383 × 3288 pixels) Red, Green, Blue (RGB) sensor, whereas Phantom 4 is equipped with a 20-megapixel, 2.54 cm RGB sensor. UAS data were collected multiple times during the season (Table 1) at an altitude of 25 m with 90% front and side overlap in 2016, and 85% in 2021. This resulted in a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 0.9 cm/pixel in 2016 and 0.65 cm/pixel in 2021. Flights were not conducted beyond 100 DAP in 2021, as previous data from 2016 indicated that canopy height (CH) plateaued after this stage. A total of 9 semi-permanent Ground Control Points (GCP) were installed across the field as geodetic benchmarks for multi-temporal image georeferencing. The GCPs are 0.6 m × 0.6 m plywood boards painted yellow and black for easy recognition during image processing. In 2016, GCPs were surveyed using a dual frequency, post processed kinematic (PPK) GPS system, model 20 Hz V-Map Air (Micro Aerial Project L.L.C., Gainesville, FL). In 2021 the position of GCPs was surveyed using Real Time Kinematic Global Positioning System (RTK-GPS) device, Emlid Reach RS2 (EMLID, Hong Kong, China). GCPs were used for improving absolute accuracy as well as validation of georeferencing. Agisoft Metashape software (Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) was used for image processing to generate geospatial data products such as 3D point cloud, orthomosaic, DSM (Digital Surface Model), and DTM (Digital Terrain Model) (Fig. 2A)28.

Feature generation and data extraction

We obtained CH from the Canopy Height Model (CHM) which was obtained by subtracting the DTM from the DSM37 (Fig. 2B). DTMs were generated from UAS data collected before planting and DSMs were the surface models acquired throughout the growing season38. A plot boundary shape file was generated by using the plot boundary tool in the UAS hub (https://uashub.tamucc.edu) and was overlaid on the CHM to extract plot level CH data.

Nonlinear growth models

The cotton crop growth and development follow an S-shaped sigmoidal curve39 as shown in (Fig. 3). Therefore, the multi-temporal CH measurements obtained throughout the growing period were plotted. Multiple 3P, 4P, and 5P models were used to fit cotton CH data, as they represent common nonlinear growth functions with increasing parameter complexity. This allows comparison of model flexibility and goodness-of-fit in describing canopy growth. Curves such as sigmoid, logistic, Weibull, Gompertz, Hill, and Chapman were chosen to compare their ability to describe growth over time. We tested several functions that depict the S-shaped patterns representing cotton growth and development (Table 2) and were fitted using nonlinear least squares (Levenberg–Marquardt method), implemented in SigmaPlot (v15.0.0; Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA), which was also used to generate fitted curves and visualizations. Their performances were compared using coefficient of determination (R2) and the root mean square error (RMSE) to identify the best-fitting model for cotton growth.

Statistical analysis

Growth parameters for each plot were calculated using Python scripts and visualized using the Matplotlib package (Python Software Foundation, 2001). The first and second order derivatives were performed on the 5P logistic function and ten different parameters that relate to the timing and rate of growth were obtained. Using first-order derivative of the 5P logistic function we obtained the time (Tmax) and rate (Rmax) of the maximum growth rate. The growth parameters i.e., the time of onset of the exponential phase (T1), the time (T2) and rate (R2) of onset of linear phase, the time (T4) and rate (R4) of end of linear phase, and the time of onset of the steady phase (T5) were obtained by conducting second order derivative of the function. For each year, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute, 2008) to compare the effect of genotype on growth parameters. The experimental design followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with genotype as a fixed effect and replication as a random effect. To investigate the relationship between the growth parameters and the yield, linear regression analysis was conducted in Python separately for 2016 and 2021. The residuals were checked for normality and heteroscedasticity to ensure model assumptions were met. To assess the goodness of fit for the regression models, the R2 and RMSE were computed.

Results

Multi-temporal CH measurements and growth analysis

Upon plotting the multi-temporal CH measurements obtained from UAS, a similar trend (Fig. 4) was found in both years. The crop attained maximum height around 85–90 DAP with an average of 125 ± 24 cm during this time. In both years, crop growth and development follow an S-shaped sigmoidal curve39. Based on this pattern, several sigmoidal growth functions were applied to the multi-temporal CH data averaged across plots (Fig. 5). We found that the 5P logistic function had the best fit with the lowest RMSE (6.41) and highest R2 (0.98) compared to the rest of the sigmoidal functions (Table 3). This may reflect underlying asymmetry, possibly caused by variation in availability and distribution of resources such as water and fertilizer during the growing season. Therefore, an additional parameter in the growth function to address this asymmetry. Based on these results, the 5P logistic function was selected to demonstrate growth analysis and to obtain growth parameters. This function has the potential to provide the flexibility needed to fit the data obtained across the environment.

Growth parameters extraction

The first and second order derivatives were performed on the 5P logistic function and ten different parameters that relate to the timing and rate of growth (Table 4) were obtained. As shown in Fig. 6a, T1 represents the time when the growth of the plant is at initiation of canopy expansion, resulting in the gradual development of its canopy structure. T2 and R2 represent the time and rate during onset of the linear phase when the canopy growth starts to increase. At this stage, the plant produces squared buds that affect yield potential. Over time these floral buds develop into mature cotton bolls. Tmax and Rmax depict the time and rate when the canopy growth rate is at its peak. T4 and R4 represent the end of the linear phase, where the plant growth rate gradually declines. T5 shows the onset of the steady phase which means plant growth is at minimum and directs energy towards boll development. This is also the reason that a negative slope on the growth rate curve is observed at 50–80 DAP (Fig. 6). DL describes the linear phase of the plant and DE represents the whole exponential growth phase. Performing the first-order derivative of the 5P logistic function we obtained the time (Tmax) and rate (Rmax) of the maximum growth rate (Eq. 1 and Fig. 6b). The growth parameters i.e., the time of onset of the exponential phase (T1), the time (T2) and rate (R2) of onset of linear phase, the time (T4) and rate (R4) of end of linear phase, and the time of onset of the steady phase (T5) were obtained (Fig. 6) by conducting second order derivative of the function (Eq. 2 and Fig. 6c).

where, a is the starting point for the growth of the canopy after planting, b is the slope of the curve, x0 is the time at which the maximum growth occurs or inflection point, and y0 is the highest maximum growth before harvest, c is an asymmetric factor (c > 0).

Genotypic variation in growth parameters

As the cotton genotypes were different in different years, the analysis of variance for growth parameters was conducted separately for both years to assess the effect of genotypes on growth parameters. Significant differences were observed among the genotypes (p < 0.05) for all the parameters obtained from CH except for T1 in 2016. In 2016, T1 ranged from 9 to 19 DAP, T2 ranged from 39 to 50 DAP, R2 ranged from 1.65 to 2.79 cm day−1, Tmax ranged from 57 to 68 DAP, Rmax ranged from 2.45 to 3.11 cm day−1, T4 ranged from 72 to 85 DAP, R4 ranged from 1.75 to 3.58 cm day−1, T5 ranged from 102 to 109 DAP, DL ranged from 33 to 40 DAP, and DE ranged from 87 to 100 DAP. In 2021, T1 ranged from 26 to 42 DAP, T2 ranged from 40 to 49 DAP, R2 ranged from 2.2 to 4 cm day−1, Tmax ranged from 52 to 60 DAP, Rmax ranged from 5 to 7.3 cm day−1, T4 ranged from 59 to 66 DAP, R4 ranged from 2.5 to 3.7 cm day−1, T5 ranged from 70 to 106 DAP, DL ranged from 11 to 18 DAP, and DE ranged from 33 to 67 DAP (Fig. 7).

Box plots for all the growth parameters of CH from 2016 and 2021. Growth parameters included are the time of onset of the exponential phase (T1), the time (T2) and rate (R2) of onset of linear phase, the time (Tmax) and rate (Rmax) of maximum growth, the time (T4) and rate (R4) of end of linear phase, the time of onset of the steady phase (T5), and duration of linear (DL) and exponential (DE) phases.

T1 was earlier in 2016 compared to 2021, while T2, Tmax, T4, and T5 were earlier in 2021. This indicates that, compared to 2016, it took longer for cotton in 2021 to reach an exponential growth phase, but it reached maximum growth rate and maximum height earlier. Furthermore, the plants grew with lower R2, Rmax, and R4 in 2016 compared to 2021, indicating 2021 had higher growth rate. Difference in DAP of growth parameters can be attributed to the differences in rainfall pattern over both years (Fig. 1a). Within the first 45 DAP (Feb 27th to Apr 13th in 2021; and Apr 1st to May 15th in 2021) cotton received almost no rain in 2021 compared to about 50 mm in 2016. This could have led to faster early growth and early T1 in 2016. For the later part of the life cycle, rainfall was erratic in 2016 and consistent in 2021 leading to cumulative rainfall of 2016 (295 mm) to be less than half of 2021 (620 mm). This consistent rain of 2021 might have been the reason behind early T2, Tmax, T4 and T5, and higher R2 and Rmax in 2021 compared to 2016. The difference in growth parameters in 2016 could be drought response of cotton plants44. This drought response might also explain the longer DL and DE in 2016 compared to 2021.

Relationship between growth parameters and yield

Comparing the Pearson’s correlation coefficients we observed that growth parameters T2, DL, R2, and Rmax were significantly correlated (P < 0.01) with cotton yield in both 2016 and 2021 (Table 5). Among these, Rmax had the highest positive correlation with yield (r = 0.67 in 2016 and r = 0.82 in 2021). This suggests that a higher maximum growth rate leads to a better yield. Significant correlation with R2 indicates that faster early growth contributes to higher yield and DL, the time it takes to grow from T2 to T4, shows that a longer linear growth phase is linked to better yield. These traits are essential for cotton yield because they reflect the plant’s ability to grow quickly and sustain growth over time. However, the time of onset of growth phases (T1 through T5) showed insignificant or poor correlation. This may be due to differences between varieties and variations in environmental conditions, which affect growth timing but not necessarily final cotton yield. Linear regression of Rmax with cotton yield also suggest that maximum growth rate shows potential as an indicator for estimating cotton yield, although its predictive strength varies across years and environments (Fig. 8).

Assessing the maturity of cotton using growth parameters

Maturity rating of cotton cultivar was assessed using T5 growth parameter. Twenty varieties from the 2021 season with documented maturity ratings as short season, medium season, and full season were selected45. Using the information from this previous study, we classified T5 values ≤ 80 DAP as short season, values between 81 and 90 as medium season, and values above 90 as full season. Overall classification accuracy was 80% (Table 6). Good accuracy in rating maturity in cotton cultivars using T5 growth parameter showed that cotton varieties with early onset of steady phase had early physiological maturity. This is because the onset of steady phase coincides with ceasing of vegetative growth and beginning of flowering, followed by boll formation and development, and physiological maturity is the only way forward for a cotton plant.

Discussion

Model performance

For our study, the multi-temporal CH data obtained from UAS was analyzed in detail to extract physiologically significant growth parameters. The CH data effectively captured growth patterns and developmental stages, aligning with prior studies that linked cotton’s morphological traits to its growth phases5. Traits associated with plant growth, architecture, and development were generated and analyzed, following approaches outlined in earlier research46. By examining growth rates, the study drew strong parallels between plant physiology and growth characteristics, consistent with prior findings47,48. Additionally, modeling relative growth rates enhanced the analysis of growth performance and efficiency49. For a detailed evaluation of crop growth over time, non-linear models such as sigmoidal growth functions were used, which are known for their effectiveness in analyzing initial growth stages50. This study uniquely applied these models to UAS-derived data in plant growth research, addressing a gap in the current literature. Several logistic growth functions, including 3P, 4P, and 5P models, were tested for analyzing cotton growth51,52. The 5P logistic function proved to be the most robust model with lowest RMSE (6.41) and highest R2 (0.98) for analyzing multi-temporal CH measurements compared to other functions. Its best fit (lowest RMSE and highest R2) can be attributed to its ability to address the inherent asymmetry in cotton growth. This additional parameter in the 5P model enabled a better representation of real-world crop growth processes compared to simpler models like the 4P and 3P logistic functions, which struggle with asymmetric data due to delayed saturation phase and prolonged early growth53. Similar studies, such as those by Gottschalk & Dunn19 and Pinheiro & Bates50, have emphasized the importance of additional parameters for capturing asymmetry in biological systems. Other 5P functions compared in this study such as 5P Weibull, also evaluated in this study, can model growth with flexibility but it often requires more parameters to achieve a similar fit for complex biological systems leading to overfitting or less intuitive biological interpretations52. The 5P Sigmoid is capable of modeling S-shaped growth but might not adapt as effectively to the specific growth patterns of cotton where growth rates slow due to resource limitations, unlike the logistic which naturally accommodates this through its parameter structure54.

Growth parameters

The use of the first- and second-order derivatives of the 5P logistic function was the next step to understand cotton growth dynamics. Our approach to derive first and second order derivative and use its parameters to correlate cotton development has been previously done using 4P logistic function55. Both studies found significant correlation between the maximum growth rate (Rmax) (r-value of 0.71 compared to our 0.82), identified as the inflection point in the first-order derivative, and the duration of the linear phase (DL) of CH with yield. Parameters T2 and T4 represent the transition from exponential to linear growth phases. These parameters represent the linear phase duration of 40 to 80 days after emergence and are influenced by environmental and genetic variables2,55. We found similar scenario in our study where low rainfall and subsequent drought stress caused the duration between T2 and T4 (DL) to be longer than 2021. Additionally, T1 and T5, derived using a 0.005 threshold in the second order function, are focused on the initial exponential and steady growth phases. The T5 parameter signifies the steady growth phase and is linked to boll maturation, with growth rates at T1 and T5 stages being below 1%, indicative of early lag and saturation phases. During this maturation phase, as noted by56, there’s a shift in carbohydrate allocation to developing and mature bolls, leading to reduced canopy growth and fewer new nodes or squares, a phenomenon also observed by6. These parameters were instrumental in understanding early growth trends and the maturation process in cotton crops. It is worth noting that our methodology here involved using 2016 data to build the 5P logistic and its first and second order derivative functions. These functions were then fitted using the 2021 dataset (different study with separate sets of cultivars). This approach proves the consistency and repeatability of this method across different growing seasons and cultivars which is important for agricultural crops.

Genotypic and environmental variations

Growth parameters can be used in understanding drought response mechanisms and their application in agricultural research and farming, a trend also observed in the 2016 and 2021 crop data57,58. For example, compared to 2021, higher than usual rainfall caused early T1 in 2016 but erratic rainfall later in the season caused delayed T4 and T5, longer DL and DE, and lower R2, Rmax and R4. This suggests that cotton adjusted to environmental conditions by extending the linear and exponential growth phases while reducing growth rates, likely as a drought tolerance strategy44,59. These traits suggest that cotton can optimize its growth dynamics to enhance survival and productivity under adverse conditions. Therefore, integrating growth parameters derived from UAS data into agricultural research could be used for high-throughput phenotyping of cotton for drought tolerance60. By using parameters such as Rmax, DL and DE researchers can pinpoint cultivars with enhanced drought resilience. This can help with precision farming practices as well for variable rate irrigation management in a water-limited environment.

Yield and maturity

Previous studies have discussed the use of mathematical functions in plant growth analysis and showed significant variations in growth parameters among different cotton varieties10. We used such variation in our study to estimate cotton maturity type using growth parameters T5. By classifying cotton cultivars based on their DAP to T5 values (with 80% accuracy in our study), researchers can better understand and assess how different varieties will mature under various environmental conditions. This knowledge is crucial for selecting cultivars that align with specific growing seasons or climates, thereby optimizing planting schedules, irrigation, and harvest timing. For farmers, knowing the maturity type can lead to more precise agricultural management, enhancing yield quality by ensuring that each variety is harvested at its peak maturity, which in turn affects fiber quality and market value. It is noteworthy to mention here that T5 (end of steady growth phase) being related to cotton maturity has to do with its growth physiology. Cotton crop growth habit enables the plant to simultaneously produce vegetative and reproductive structures61. As the fruit load develops, the demand for carbohydrates and nutrients increases in proportion to the number of developing fruits. However, the supply of carbohydrates reaches a limit which is set by canopy light interception. When the demand for carbohydrates exceeds the supply, the crop temporarily pauses its vegetative growth and begins a phenomenon commonly named as “cutout”2, which represents physiological maturity. Cotton crop maturity is a complex trait and is associated with yield, fiber quality, and net returns.

Growth parameters like Rmax, R2, DL, and DE showed significant correlation with cotton yield. This might have been because the high early to maximum growth rate translates to taller plants with potentially higher leaf area, a greater number of nodes and branches leading to more squares. Moreover, the linear growth phase of cotton begins at branch development stage and ends at pin head square stage, physiologically crucial stages for better reproductive growth in cotton2,62. Yield estimation using growth parameter Rmax suggests that mid-season yield predictions can be made with significant accuracy. Such estimations allow researchers to evaluate the efficacy of new cultivars or agricultural techniques under real-world conditions, while farmers can optimize resource allocation, like water and nutrients, for maximum yield potential. Seed cotton yield in 2016 was lower than 2021 which could be due to erratic rainfall and drought stress during mid to late season leading to poor reproductive growth. However, the comparative analysis between 2016 and 2021 showed that yield estimation was less accurate in 2016 (R2 of 0.46 compared to 0.68 in 2021). Also, average Rmax value in 2016 (2.75 cm day-1) was half that of 2021 (5.95 cm day-1) but average yield in 2016 (1301 kg ha-1) was about two-thirds of 2021 (1987 kg ha-1); and final CH were similar (123 cm and 125 cm) in both years. This shows that though drought stress affected growth rates, cotton plants compensated for the drought at later stages. Previous drought studies on cotton have explained the physiology behind this compensatory effect63. High overall accuracy (80%) in rating maturity in cotton cultivars using T5 growth parameter showed that cotton varieties with early onset of steady phase had early physiological maturity. This is because the onset of steady phase coincides with ceasing of vegetative growth and beginning of flowering, followed by boll formation and development, and physiological maturity is the only way forward for a cotton plant. Its use in maturity classification generally aligns with crop growth dynamics, with full-season varieties showing clear separation. However, medium-maturity varieties were more ambiguous, with lower F1 score (0.60). This could be due to overlapping physiological timing and natural variation in growth rates. The high F1 scores for short (0.89) and full (0.71) season types indicate that early and late transitions are more distinct. However, limited sample size (n = 20) constrains the robustness of these classifications. Further studies with more sample number could improve the reliability of T5 as a physiological maturity indicator.

Limitations and future work

This study discussed that the compensatory effect mainly affected leaf area, root biomass and reproductive parts such as bolls and fiber. This scenario highlights a limitation of using CH for growth parameter analysis in cotton, where abnormal environmental factors can significantly influence the accuracy of yield predictions. However, it is important to note that we used CH because it could be measured reliably using UAS. Our priority was using UAS for cotton phenotyping to be used for growth parameter study as a proof of concept. Further studies are required to use UAS measured phenotypes such as canopy cover, canopy volume, lateral growth, total leaf area, or node count for growth parameter study. Moreover, this study did not account for management and architectural traits such as growth regulator application or fruit branch density. Incorporating these factors could further refine UAV-based growth assessments in future work. However, as plants structures become more complex, their increasing leaf, stem size and number lead to more obstruction complicating plant growth analysis and UAS data collection64,65.

Conclusion

The use of UAS derived plant phenotypes combined with nonlinear growth models improved characterization of the indeterminate growth patterns of cotton. 5P logistic model providing the best fit due to its ability to capture asymmetry in growth data. Second order derivatives of this model were used to extract growth parameters describing the rate and timing of growth which showed correlations with yield outcomes. Mid-season parameters such as Rmax, representing peak growth rate, can estimate potential yield and can inform management of inputs like water, fertilizers, and growth regulators. T5, marking the onset of the steady growth phase, was used to classify cotton maturity types, achieving 80% accuracy for short, mid, and full season varieties. This classification can support better timing of planting, irrigation, and harvest to optimize fiber quality and yield. Environmental variability, such as drought in 2016, reduced prediction accuracy and represents the influence of conditions beyond CH on yield. Incorporating additional UAS derived traits such as canopy cover, volume, or spectral indices, could improve growth modeling under diverse conditions and enhance cultivar evaluation for breeding programs. The spatiotemporally high resolution data enabled by UAS provides valuable opportunities to advance crop growth analysis and management. These methods may be extended to other crops and environments to support more resilient and productive agriculture.

Data availability

The datasets generated are not publicly available because they are being used to prepare other manuscripts but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kohel, R. & Benedict, C. Growth analysis of cottons with differing maturities 1. Agron. J. 79(1), 31–34 (1987).

Landivar, J. A., Reddy, K. R. & Hodges, H. F. Physiological simulation of cotton growth and yield. Physiol. Cotton 2010:318–331.

Byrd, S. Defining cutout in cotton. 2018.

Li, M., Liu, J., Yang, W., Sun, X. & Guo, Z. Structure-revealing low-light image enhancement via robust retinex model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27(6), 2828–2841 (2018).

Ritchie, G. L. Ground-based and aerial remote sensing methods for estimating cotton growth, water stress, and defoliation. University of Georgia Athens; 2007.

Landivar, J. & Benedict, J. Monitoring system for the management of cotton growth and fruiting. Bull B 1996, 2 (1996).

Archontoulis, S. V. & Miguez, F. E. Nonlinear regression models and applications in agricultural research. Agron. J. 107(2), 786–798 (2015).

Gompertz, B. XXIV. On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies. In a letter to Francis Baily, Esq. FRS &c. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. London 1825(115):513–583.

Tessmer, O. L., Jiao, Y., Cruz, J. A., Kramer, D. M. & Chen, J. Functional approach to high-throughput plant growth analysis. BMC Syst. Biol. 7, 1–13 (2013).

Hunt, R. Plant growth analysis: second derivatives and compounded second derivatives of splined plant growth curves. Ann. Bot. 50(3), 317–328 (1982).

Richards, F. J. A flexible growth function for empirical use. J. Exp. Bot. 10(2), 290–301 (1959).

Fresco, L. A model for plant growth. Estimation of the parameters of the logistic function. Acta Botanica Neerlandica 22(5), 486–489 (1973).

Paine, C. T. et al. How to fit nonlinear plant growth models and calculate growth rates: An update for ecologists. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3(2), 245–256 (2012).

France, J. & Thornley, J. H. Mathematical models in agriculture; 1984.

Nelder, J. A. The fitting of a generalization of the logistic curve. Biometrics 17(1), 89–110 (1961).

Rodbard, D. Statistical quality control and routine data processing for radioimmunoassays and immunoradiometric assays. Clin. Chem. 20(10), 1255–1270 (1974).

Badrick, T., Ward, G. & Hickman, P. The effect of the immunoassay curve fitting routine on bias in troponin. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 61(2), 188–195 (2023).

Cao, L., Shi, P.-J., Li, L. & Chen, G. A new flexible sigmoidal growth model. Symmetry 11(2), 204 (2019).

Gottschalk, P. G. & Dunn, J. R. The five-parameter logistic: A characterization and comparison with the four-parameter logistic. Anal. Biochem. 343(1), 54–65 (2005).

Dhondt, S., Wuyts, N. & Inzé, D. Cell to whole-plant phenotyping: The best is yet to come. Trends Plant Sci. 18(8), 428–439 (2013).

Moeckel, T. et al. Estimation of vegetable crop parameter by multi-temporal UAV-borne images. Remote Sens. 10(5), 805 (2018).

Maimaitijiang, M. et al. Soybean yield prediction from UAV using multimodal data fusion and deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111599 (2020).

Bennett, R., Burow, M., Balota, M., Chagoya, J., Sarkar, S., Sung, C.-J. et al. Response to drought stress in a subset of the US peanut mini-core evaluated in Oklahoma, Texas, and Virginia. Peanut Sci. 2022, 49(1).

Chapu, I. et al. Exploration of alternative approaches to phenotyping of late leaf spot and groundnut rosette virus disease for groundnut breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 912332 (2022).

Xie, C. & Yang, C. A review on plant high-throughput phenotyping traits using UAV-based sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 178, 105731 (2020).

Sarkar, S. Development of high-throughput phenotyping methods and evaluation of morphological and physiological characteristics of peanut in a sub-humid environment. 2020.

Jung, J. et al. The potential of remote sensing and artificial intelligence as tools to improve the resilience of agriculture production systems. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 70, 15–22 (2021).

Bhandari, M. et al. Unmanned aerial system-based high-throughput phenotyping for plant breeding. Plant Phenome J. 6(1), e20058 (2023).

Sarkar, S. & Jha, P. K. Is precision agriculture worth it? Yes, may be. J Biotechnol Crop Sci 9(14), 4–9 (2020).

Weiss, M., Jacob, F. & Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111402 (2020).

Balota, M., Sarkar, S., Bennett, R. S. & Burow, M. D. Phenotyping peanut drought stress with aerial remote-sensing and crop index data. Agriculture 14(4), 565 (2024).

Sarkar, S. et al. Evaluation of the US peanut germplasm mini-core collection in the Virginia-Carolina region using traditional and new high-throughput methods. Agronomy 12(8), 1945 (2022).

Chawade, A. et al. High-throughput field-phenotyping tools for plant breeding and precision agriculture. Agronomy 9(5), 258 (2019).

Sarkar, S. et al. Aerial high-throughput phenotyping of peanut leaf area index and lateral growth. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 21661 (2021).

Sarkar, S. et al. Integrating remote sensing and soil features for enhanced machine learning-based corn yield prediction in the Southern US. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 25(2), 543 (2025).

Bhandari, M. High-Throughput Field Phenotyping in Wheat Using Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). Texas A&M University; 2020.

Chang, A., Jung, J., Maeda, M. M. & Landivar, J. Crop height monitoring with digital imagery from unmanned aerial system (UAS). Comput. Electron. Agric. 141, 232–237 (2017).

Sarkar, S. et al. High-throughput measurement of peanut canopy height using digital surface models. Plant Phenome J. 3(1), e20003 (2020).

Liu, J.-H. et al. Simulation of crop growth, time to maturity and yield by an improved sigmoidal model. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 7030 (2018).

Nelder, J. A. A note on some growth patterns in a simple theoretical organism. Biometrics 17(2), 220–228 (1961).

Winsor, C. P. The Gompertz curve as a growth curve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 18(1), 1–8 (1932).

Hill, A. V. The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of hemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J. Physiol. 40, 4–7 (1910).

Chapman, S., Hammer, G. & Palta, J. Predicting leaf area development of sunflower. Field Crop Res 34(1), 101–112 (1993).

Blum, A. Plant breeding for water-limited environments: Springer Science & Business Media; 2010.

Silvertooth, J. C. General maturity groups for cotton varieties (College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ), 2015).

Berger, B., Parent, B. & Tester, M. High-throughput shoot imaging to study drought responses. J. Exp. Bot. 61(13), 3519–3528 (2010).

Brand, D. G., Weetman, G. F. & Rehsler, P. Growth analysis of perennial plants: the relative production rate and its yield components. Ann. Bot. 59(1), 45–53 (1987).

Turnbull, L. A., Paul-Victor, C., Schmid, B. & Purves, D. W. Growth rates, seed size, and physiology: do small-seeded species really grow faster. Ecology 89(5), 1352–1363 (2008).

Pommerening, A. & Muszta, A. Methods of modelling relative growth rate. For. Ecosyst. 2, 1–9 (2015).

Pinheiro, J. C. & Bates, D. M. Extending the basic linear mixed-effects model. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS 2000:201–270.

Sun, S. et al. In-field high throughput phenotyping and cotton plant growth analysis using LiDAR. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 16 (2018).

Yin, X., Goudriaan, J., Lantinga, E. A., Vos, J. & Spiertz, H. J. A flexible sigmoid function of determinate growth. Ann. Bot. 91(3), 361–371 (2003).

Prentice, R. L. A generalization of the probit and logit methods for dose response curves. Biometrics 1976:761–768.

Wen, Y., Liu, K., Liu, H., Cao, H., Mao, H., Dong, X. et al. Comparison of nine growth curve models to describe growth of partridges (Alectoris chukar). J. Appl. Animal Res. 2019.

Gregorczyk, A. The logistic function-its application to the description and prognosis of plant growth. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 60(1–2), 67–76 (1991).

da Costa, V. A. & Cothren, J. T. Cotton flowering and fruiting: Control and modification with plant growth regulators. Flower. Fruit. 2012:79.

Zhao, H. et al. Recent advances and future perspectives in early-maturing cotton research. New Phytol. 237(4), 1100–1114 (2023).

Sarkar, S., Ramsey, A. F., Cazenave, A.-B. & Balota, M. Peanut leaf wilting estimation from RGB color indices and logistic models. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 658621 (2021).

Dinkar, V., Sarkar, S., Pandey, S. & Antre, S. H. Plant stress phenotyping: Current status and future prospects. Adv Agron 188, 247 (2024).

Sarkar, S., Rai, A. & Jha, P. K. Remote Sensing and High-Throughput Techniques to Phenotype Crops for Drought Tolerance. In: Soil-Water, Agriculture, and Climate Change: Exploring Linkages. Springer; 2022: 107–129.

Mauney, J. R. Anatomy and morphology of cultivated cottons. Cotton 57, 77–96 (2015).

Oosterhuis, D. M. Growth and development of a cotton plant. Nitrogen Nutr. Cotton Pract. Issues 1990:1–24.

Niu, J. et al. The compensation effects of physiology and yield in cotton after drought stress. J. Plant Physiol. 224, 30–48 (2018).

Paproki, A., Sirault, X., Berry, S., Furbank, R. & Fripp, J. A novel mesh processing based technique for 3D plant analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 1–13 (2012).

Paulus, S., Schumann, H., Kuhlmann, H. & Léon, J. High-precision laser scanning system for capturing 3D plant architecture and analysing growth of cereal plants. Biosys. Eng. 121, 1–11 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Cotton Incorporated (Texas State Support Committee project number 17-519TX) for funding our project.

Declaration of plant materials used

The seeds of cotton genotypes used in this study were obtained from respective breeders, Smith, Hague, Dever and Stelly; and the commercial variety seeds were obtained from respective companies such as Deltapine and Phytogen with the provider granting permission for their collection and use. Formal identification of the plant material was conducted by Dr Juan Landivar, Texas A&M AgriLife research, Corpus Christi, TX and a voucher specimen has been deposited at Texas A&M AgriLife Research station at Corpus Christi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., J.L., N.R., S.A. conceptualized the study, designed the experiments, and acquired funding. M.M., J.J., J.L.S. did field and aerial data acquisition, J.M. did experimental design and established these field study, L.Z. S.S analyzed the data and fitted the functions, S.P., S.S. drafted the manuscript, created the tables and figures, and M.B. made significant edits to it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Palla, S., Sarkar, S., Zhao, L. et al. Growth analysis of cotton using UAS derived multi temporal canopy features. Sci Rep 15, 43759 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27174-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27174-8