Abstract

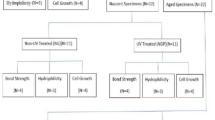

This in-vitro study evaluated the retention forces of traditional metal ball attachments compared with PEEK-milled ball attachments, combined with either nylon or PEEK retentive caps. A total of 40 samples were equally divided into four groups: Group I (metal ball with nylon cap), Group II (metal ball with PEEK cap), Group III (PEEK ball with nylon cap), and Group IV (PEEK ball with PEEK cap). Retention was measured using a Testometric machine at five intervals: initial removal (T0), and after 1 (T1), 6 (T2), 12 (T3), and 24 (T4) months of simulated aging. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni tests (α = 0.05). Results showed that groups with PEEK caps (Groups II and IV) demonstrated significantly higher retention values compared with nylon-cap groups (Groups I and III) at most time points, although all groups exhibited a progressive reduction over time. The use of PEEK as both ball attachment and retentive cap may provide improved long-term retention compared with conventional metal/nylon systems; however, further clinical studies are required to validate these in-vitro findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In elderly patients, tooth loss and alveolar bone resorption often destabilize mandibular dentures, causing functional and nutritional problems. Overdentures (ODs)—removable prostheses supported by teeth, roots, or implants1,2—use attachments to enhance retention3. Precision attachments with nylon caps need periodic replacement due to wear2,4. Ball attachments are favored for their simplicity, low cost, and ease of use, providing retention forces of 2–15 N5,6,7,8.

The main disadvantages of this system are related to functional movements during insertion and removal of the prosthesis, as well as parafunctional habits, oral microbiota, and intraoral conditions9. These factors contribute to a gradual reduction in retention force over time, necessitating frequent replacement and maintenance, particularly in situations where implants are not parallel10.

The longevity and performance of overdenture attachments depend on their retention, which is influenced by material composition, wear, and insertion–removal cycles; commonly used systems include metal and PEEK ball attachments with nylon or PEEK caps11,12,13,14.

Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) is a member of the polyaryletherketone (PAEK) family, known for its excellent chemical and heat resistance, beneficial toughness, high strength, good processability, as well as a balance of flexibility and rigidity15. PEEK is a metal-free material that can be used in dental restorations15.

PEEK is a high-temperature thermoplastic polymer with a melting point of approximately 343 °C, a density ranging from 1.3 to 1.5 g/cm3, and an elastic modulus between 3 and 4 GPa16. In comparison, titanium has an elastic modulus of 113 GPa, and zirconia reaches 204 GPa16. Therefore, PEEK presents an attractive alternative to traditional metal alloys and ceramic dental materials17.

Despite its advantages, PEEK has several disadvantages. It is relatively expensive, its low surface energy leads to poor cell adhesion, and it presents challenges in manufacturing18.

PEEK has been introduced into dentistry as a biocompatible, mechanically stable, chemically inert, and aesthetically pleasing material18. In removable prosthetics, PEEK can be used to for various applications including: denture bases, partial denture retainer clasps, telescopic crowns, frameworks, and as a retentive cap for metal ball attachments19,20.

PEEK have been examined as a framework material or as a retentive element in overdentures, but no investigations have evaluated the combined use of PEEK-milled ball attachments and PEEK-milled retentive caps. This represents a novel approach that may provide enhanced retention stability over time compared with conventional metal/nylon systems.

This in-vitro study aims to evaluate and compare the retention forces of four attachment systems: Metal Ball Attachments with Nylon caps (MBA-NC), Metal Ball Attachments with PEEK retentive caps (MBA-PC), PEEK Ball Attachments with Nylon caps (PBA-NC), and PEEK Ball Attachments with PEEK retentive caps (PBA-PC).

The findings are expected to highlight the clinical relevance of PEEK as a potential alternative to metal attachments in implant overdentures, offering improved long-term retention, reduced maintenance, and enhanced prosthesis performance.

The null hypothesis assumed no significant differences in initial retention or retention loss over time between ball attachments or retentive caps milled from PEEK and those made from other materials.

Materials and methods

The required sample size was initially estimated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9) based on the study of El Charkawi and Abdelaziz20, which reported an effect size (Cohen’s f) of 0.65. This yielded a total of 40 specimens (10 per group) to achieve 90% power for a four-group ANOVA at a significance level of α = 0.05.

In addition, a pilot study involving 20 mechanical units (ball–cap assemblies) was conducted to verify the adequacy of this estimate and to assess the variability of the retention force among material combinations. Based on the pilot data, an effect size (Cohen’s f) of approximately 0.9 was obtained, corresponding to a required total sample size of 20 specimens (5 per group) at α = 0.05. Consequently, the larger calculated sample (n = 10 per group; total N = 40) was adopted to enhance the robustness and reliability of the study findings.

The study sample consisted of 40 specimens, divided into four groups as follows: Group I –Metal Ball Attachments with Nylon Caps (MBA-NC; n = 10); Group II – Metal Ball Attachments with PEEK retentive Caps (MBA-PC; n = 10); Group III – PEEK Ball Attachments with Nylon Caps (PBA-NC; n = 10); Group IV – PEEK Ball Attachments with PEEK retentive Caps (PBA-PC; n = 10).

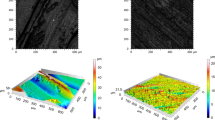

Initially, the digital workflow began with the acquisition of the ball attachment geometry (Ball Abutment, J Dental Care, Italy) using an optical scanner i500 (Medit Corp., Seoul, South Korea) (Fig. 1). This scan was used to 3D print 20 metal ball attachments (Realloy-N+ , Really E.K, Krefeld, Germany) via CAD/CAM and to mill 20 PEEK ball attachments from PEEK discs (Marco Dental, Zhengzhou, China), ensuring identical size and shape between the metal and PEEK attachments.

The nylon caps were obtained as original components directly from the manufacturer (Elastic Retention Caps, JDEvolution, J Dental Care, Italy), which were incorporated within metal housings specifically designed to provide secure and resilient retention.

The PEEK retentive cap was then virtually designed using Exocad DentalCA, version 3.1 (Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) and further refined in Meshmixer, version 3.5 (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA).

The inner surface of the cap was modeled as a negative replica of the outer surface of the ball attachment, incorporating a 0.5 mm spacer on all aspects except the cervical margin, which was fully adapted (Fig. 2). The cap covered three-quarters of the ball and featured a groove on its outer surface to allow fixation with Type II Self-Curing acrylic (HUGE Denture Base Polymers, China).

A 0.5 mm vertical spacer was incorporated into the cap design to allow limited vertical and slight rotational movement of the cap over the ball attachment, minimizing friction and mechanical stress. This controlled freedom helps preserve the retentive force overtime and prevents trauma to the surrounding gingival tissues. The neck of the cap terminates 0.5 mm above the ball attachment neck, enabling a downward movement of equal magnitude without tissue interference. This design has been validated and patented (No. 2025020005-13022025).

The design was exported as an STL file to the CAM system for milling the attachments and retentive caps from PEEK discs (Marco Dental Co., Zhengzhou, China) using a milling machine SHARP2-5X (DOF Inc., Seoul, South Korea). Each ball attachment and retentive cap were placed separately into acrylic blocks (1 × 1 × 1 cm diameters) vertically using a surveyor, the cervical margin was 2 mm above the acrylic surface (Fig. 3).

The undercut areas were sealed using red wax (Cavex, Haarlem, The Netherlands) and rubber dam material, simulating the direct intraoral pickup technique. The retentive caps (each cap individually) were placed onto the ball attachments, and the specimens were numbered accordingly.

Acrylic blocks were used to standardize sample dimensions and material properties, ensuring uniform testing conditions. Attempts to replicate the spiral shape of commercial ball-and-socket implants via intraoral scanning were unsuccessful, and STL files were not provided by the implant company. Using extracted teeth would have required individual cores and caps for each sample, increasing time and cost while introducing variability that could confound retention force comparisons.

Then, the specimen was immersed in artificial saliva during the mechanical testing (insertion and removal cycles) to simulate the intraoral environment. The artificial saliva was prepared at the Faculty of Science according to the formula Pytko-Polonczyk et al.21.

The specimens were placed in universal testing machine (Testometric Co. Ltd., Rochdale, England). The part containing the ball attachment was fixed in the lower compartment of the machine, while the part containing the retentive cap was secured in the movable upper compartment.

The test was carried out at a crosshead speed of 50 mm/min with removal parallel to the axis of the ball attachment, in the presence of artificial saliva between the retentive cap and the ball attachment.

The retention values were recorded at the initial stage and after 90 (C 1), 540 (C2), 1080 (C3), 2160 (C4) insertion and removal cycles which equivalent three daily insertion and removal cycle for 1 (T1), 6 (T2), 12 (T3), 24 (T$) months by the patient.

Retention values were recorded at T0 (The first removal of the retentive cap from the ball attachment), T1 (1 month of artificial ageing; 90 insertion–removal cycles), T2 (6 months of artificial ageing; 540 insertion–removal cycles), T3 (12 month of artificial ageing; 1080 insertion–removal cycles), and T4 (24 month of artificial ageing; 2160 insertion–removal cycles).

All specimens were prepared by a single calibrated operator to minimize variability. The universal testing machine was calibrated before testing. Specimen dimensions were standardized using acrylic blocks (10 × 10 × 10 mm). The same retentive cap was used for each specimen throughout all insertion–removal cycles to simulate clinical long-term use.

Data normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction was used to detect intergroup differences at each time point. Effect sizes (η2) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to complement p-values (0.05). Descriptive statistics—including mean, standard deviation, standard error, minimum, and maximum—were reported. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMM) was used to account for repeated measures within each sample. The fixed effects included Ball Material (Metal vs. PEEK), Cap Material (Nylon vs. PEEK), and Time (T0–T4), as well as all possible interactions. Sample ID was treated as a random effect to model intra-sample dependency, and model parameters were estimated via Maximum Likelihood (ML). Wald chi-square tests were used to assess the significance of the fixed effects and their interactions. All analyses were conducted using the statsmodels package in Python, with the significance level set at α = 0.05.

Results

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p > 0.05) confirmed normal data distribution across all groups and time points, and the Cronbach’s alpha test demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.975).

At baseline (T0), both PEEK-cap groups (MBA-PC and PBA-PC) exhibited significantly higher retention forces than the nylon-cap groups (MBA-NC and PBA-NC), a trend that persisted through T1 and T2 (p < 0.01; Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 4). From T3 to T4, all groups showed progressive reductions in retention, with PBA-PC maintaining the highest values and the nylon-cap groups showing the lowest (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 4). The overall mean retention loss was greater in nylon caps (≈50–55%) than in PEEK caps (≈35–40%) (Fig. 5).

According to the Linear Mixed-Effects Model (Table 3), Cap Material had a highly significant main effect (χ2 (1) = 60.94, p < 0.001), indicating superior retention of PEEK caps compared with nylon caps. Time also exerted a strong main effect (χ2 (4) = 146.68, p < 0.001), confirming a consistent decline in retention with artificial aging. In contrast, Ball Material showed no significant main effect (χ2 (1) = 0.35, p = 0.55). Significant Cap × Time (χ2 (4) = 127.10, p < 0.001) and Ball × Cap × Time (χ2 (4) = 16.48, p = 0.0024) interactions indicated that the pattern of retention loss varied depending on both ball and cap materials.

Effect size analysis (η2 = 0.42 at T2; η2 = 0.38 at T3) supported a large treatment effect, while larger standard deviations observed in the PEEK-cap groups reflected greater intra-group variability (Table 2).

The post-hoc power analysis for the primary outcome (retention at T4) showed an achieved power > 0.99 for the overall ANOVA (Cohen’s f = 1.22, α = 0.05), confirming adequate power to detect major between-group differences. The specific MBA-PC versus PBA-PC comparison yielded a power of ≈ 0.47, indicating reduced sensitivity for smaller pairwise effects due to higher variability within the PBA-PC group. This limitation is further discussed in the Discussion section.

Discussion

This study investigated the retention behavior of metal and PEEK ball attachments combined with nylon and PEEK retentive caps over different artificial aging periods. The results demonstrated significant differences among the groups, with PEEK caps consistently providing higher and more stable retention compared to nylon caps. Furthermore, the combined use of PEEK ball attachments with PEEK caps (PBA-PC) showed the highest long-term retention. These findings reject the original null hypothesis, which assumed no significant differences in retention between the tested materials.

The superior performance of PEEK retentive caps may be attributed to their intrinsic material properties. Unlike nylon, which undergoes gradual wear, deformation, and fatigue with repeated insertion–removal cycles17,20,22, PEEK exhibits higher flexural strength and distributes stresses more evenly across the cap surface15,18,20. This reduces permanent deformation and explains the stability of retention values observed in the PEEK groups.

The findings of the present study are consistent with those of El Charkawi and Abdelaziz20, who reported increased retention force when using retentive caps milled from PEEK. Similarly, the results align with those of Sharaf et al.17, who observed higher retention forces for PEEK-milled caps compared to conventional caps after 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of artificial ageing. While these results collectively support the use of PEEK, it should be noted that the cited studies differed in attachment design and methodology, limiting direct comparability with the present work.

Importantly, this study highlights not only the significance of the retentive cap material but also the influence of the ball attachment material. Although both MBA-PC and PBA-PC groups maintained higher retention than nylon-cap groups, PBA-PC performed better at later intervals. This may be explained by the closer elastic modulus compatibility between PEEK ball and PEEK cap, which reduces surface abrasion compared to the metal–PEEK interface. Thus, the results suggest that the combined use of PEEK ball attachments and PEEK caps provides an additional advantage in preserving long-term retention.

The findings of the present study are consistent with those of Nassar and Abdelaziz23, who compared the retention forces of PEEK and nylon clips attached to a metal bar. Their results indicated that PEEK clip provided comparable or even superior retention due to their high resistance to surface changes and wear.

Although PEEK showed promising performance, its drawbacks must also be considered. PEEK is relatively expensive, requires specialized milling equipment, and has low surface energy that may reduce bonding24. These drawbacks highlight that despite the material’s superior mechanical behavior in this study; its clinical adoption may be influenced by cost and processing challenges.

The additional mixed-model analysis confirmed the robustness of the primary findings and provided deeper insight into the interaction between material type and time. The significant Cap × Time and Ball × Cap × Time interactions indicate that PEEK caps not only maintained superior retention compared with nylon but also exhibited a more stable retention profile across the aging intervals, particularly when combined with PEEK ball attachments.

These outcomes are consistent with Sharaf et al. study17 which found that PEEK retentive elements outperform conventional materials under cyclic loading. Similarly, Wichmann et al.25 reported that PEEK/PEKK systems maintained superior retention compared to nylon over 5,000 to 30,000 cycles.

However, caution is warranted: Mayinger et al.26 documented that not all forms of PEEK sustain their performance equally under aging, and PEEK ones with less favorable milling (or structure) degraded faster after extended artificial aging.

The novelty of this study lies in being the first to evaluate PEEK-milled ball attachments in combination with PEEK-milled retentive caps. The findings indicate that this configuration offers superior stability compared with traditional metal/nylon systems, and may reduce the need for frequent replacement of nylon caps, which are prone to rapid wear. This could translate into improved patient comfort and fewer maintenance visits.

Certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, this in-vitro model did not incorporate cyclic occlusal loading, lateral (oblique) forces, or thermal cycling, all of which are important intraoral variables that influence the long-term fatigue and wear behavior of attachment materials. In the oral cavity, repeated temperature fluctuations and multidirectional stresses accelerate surface degradation and micro-deformation, particularly in polymeric materials such as PEEK. The absence of these factors in the present setup may therefore have underestimated the actual clinical wear and retention loss of PEEK components. Second, although all specimens were prepared by a single calibrated operator to minimize variability, this may introduce operator-related bias in sample handling and processing. Third, while no visible deformations, fractures, or failures were observed in PEEK ball attachments or caps after 2160 cycles, the possibility of microstructural changes cannot be excluded without further microscopic analysis.

Although the study had excellent overall power (≥ 0.99) for detecting major between-group differences, the post-hoc analysis revealed limited sensitivity (≈0.47) for smaller pairwise effects, particularly between MBA-PC and PBA-PC. This likely reflects variability within the PEEK-based groups. Still, the consistent trends and robustness of the mixed-model analysis support the reliability of the findings. Further studies with larger samples and extended aging cycles are warranted to confirm these results and clarify minor intergroup differences.

Given these limitations, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the present findings directly to clinical practice. Real-world variables—including patient-specific oral hygiene, implant angulation, and frequency of prosthesis removal—may substantially affect outcomes. Future investigations should incorporate thermomechanical aging and multidirectional load simulation, as well as long-term randomized clinical trials, to confirm whether the promising in-vitro performance of PEEK translates into superior clinical effectiveness.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this in-vitro study, ball attachments combined with PEEK retentive caps demonstrated higher and more stable retention than nylon caps over simulated aging. The combination of PEEK ball attachments and PEEK caps (PBA-PC) showed the greatest long-term retention, suggesting potential advantages over conventional metal/nylon systems.

Data availability

The data provided for the results presented in this study is available through the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- OD:

-

Overdenture

- PEEK:

-

Polyetheretherketone

- PAEK:

-

Polyaryletherketone

- MBA-NC:

-

Metal ball attachments with nylon caps

- MBA-PC:

-

Metal ball attachments with PEEK retentive caps

- PBA-NC:

-

PEEK ball attachments with nylon

- PBA-PC:

-

PEEK ball attachments with PEEK retentive caps

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

References

Leong, J. Z., Beh, Y. H. & Ho, T. K. Tooth-supported overdentures revisited. Cureus 16(1), e53184. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.53184 (2024).

Ferro, K. J. et al. The glossary of prosthodontic terms: Ninth edition. J. Prosthet. Dent. 117(5S), e1–e105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.12.001 (2017).

Hobrink, J. et al. Prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients: Complete dentures and implant-supported prostheses (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2003).

Stalder, A. et al. Biological and technical complications in root cap-retained overdentures after 3–15 years in situ: A retrospective clinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 25(4), 2325–2333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03555-3 (2021).

Yalamolu, S. S. S., Bathala, L. R., Tammineedi, S., Pragallapati, S. & Vadlamudi, C. Prosthetic journey of magnets: A review. J Med Life 16, 501–506. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2020-0012 (2023).

Berger, C. H. et al. Root-retained overdentures: Survival of abutment teeth with precision attachments on root caps depends on overdenture design. J Oral Rehabil 47(10), 1254–1263. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13060 (2020).

Wakam, R., Benoit, A., Mawussi, K. B. & Gorin, C. Evaluation of Retention, Wear, and maintenance of attachment systems for single- or two-implant-retained mandibular overdentures: A systematic review. Materials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15051933 (2022).

Payne, A. G. et al. 2018 Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Attachment systems for implant overdentures in edentulous jaws. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 10(10), CD008001. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008001.pub2 (2018).

de Campos, M. R., Botelho, A. L. & Dos Reis, A. C. Reasons for the fatigue of ball attachments and their O-rings: A systematic review. Dent Med. Probl. 60(1), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.17219/dmp/146719 (2023).

Andriessen, F. S., Rijkens, D. R., Van Der Meer, W. J. & Wismeijer, D. W. Applicability and accuracy of an intraoral scanner for scanning multiple implants in edentulous mandibles: A pilot study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 111(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.07.010 (2014).

Osman, R. B. & Abdel Aal, M. A. H. Comparative assessment of retentive characteristics of nylon cap versus retention sil. in ball-retained mandibular implant overdentures. A randomized clinical trial. Egypt. Dental J. 65(2), 1787–1794 (2019).

Fayed, M. S., Elsherbini, N. N., Mohsen, B. & Osman, R. Digital wear analysis and retention of poly-ether-ether-ketone retentive inserts versus conventional nylon inserts in locator retained mandibular overdentures: In-vitro study. Clin Oral Investig 28(5s), 468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05831-y (2024).

Kang, T. Y., Kim, J. H., Kim, K. M. & Kwon, J. S. In vitro effects of cyclic dislodgement on retentive properties of various titanium-based dental implant overdentures attachment system. Materials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12223770 (2019).

Abdel Hamid, S. M., Selima, R. A. & Basiony, M. Z. Surface topography changes and wear resistance of different non-metallic telescopic crown attachment materials in implant retained overdenture (prospective comparative in vitro study). BMC Oral Health 24(1), 1123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04839-w (2024).

Parate, K. P., Naranje, N., Vishnani, R. & Paul, P. Polyetheretherketone material in dentistry. Cureus 15(10), e46485. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46485 (2023).

Brizuela, A. et al. Influence of the elastic modulus on the osseointegration of dental implants. Materials (Basel) 12(6), 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12060980 (2019).

Sharaf, M. Y., Eskander, A. & Afify, M. A. Novel PEEK retentive elements versus conventional retentive elements in mandibular overdentures: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Dent 28(2022), 6947756. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6947756 (2022).

Bathala, L., Majeti, V., Rachuri, N., Singh, N. & Gedela, S. The role of polyether ether ketone (Peek) in dentistryṣ—A review. J Med Life 12(1), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2019-0003 (2019).

Skirbutis, G., Dzingutė, A., Masiliūnaitė, V., Šulcaitė, G. & Žilinskas, J. A review of PEEK polymer’s properties and its use in prosthodontics. Stomatologija 19(1), 19–23 (2017).

El Charkawi, H. G. & Abdelaziz, M. S. Novel CAD-CAM fabrication of a custom-made ball attachment retentive housing: an in-vitro study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28(1), 520. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01498-5 (2023).

Pytko-Polonczyk, J., Jakubik, A., Przeklasa-Bierowiec, A. & Muszynska, B. Artificial saliva and its use in biological experiments. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 68(6), 807–813 (2017).

Alsabeeha, N. H., Payne, A. G. & Swain, M. V. Attachment systems for mandibular two-implant overdentures: A review of in vitro investigations on retention and wear features. Int. J. Prosthodont 22(5), 429–440 (2009).

Nassar, H. I. & Abdelaziz, M. S. Retention of bar clip attachment for mandibular implant overdenture. BMC Oral Health 22(1), 227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02262-7 (2022).

Ge, Y., Zhao, T., Fan, S., Liu, P. & Liu, X. Effects of surface treatments on the adhesion strengths between polyether ether ketone and both composite resins and poly(methyl methacrylate). BMC Oral Health 25(1), 940. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-06305-7 (2025).

Wichmann, N., Kern, M., Taylor, T., Wille, S. & Passia, N. Retention and wear of resin matrix attachments for implant overdentures. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 110, 103901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103901 (2020).

Mayinger, F. et al. Retention force of polyetheretherketone and cobalt-chrome-molybdenum removable dental prosthesis clasps after artificial aging. Clin. Oral Investig. 25(5), 3141–3149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03642-5 (2021).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sana Lala: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Data curation, Investigation, Roles/writing—original draft. Ammar Almustafa Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Roles/writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Hasan Alzoubi: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lala, S., Almustafa, A. & Alzoubi, H. In vitro study of retention forces in traditional and PEEK milled ball attachments with two retentive caps. Sci Rep 15, 41750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27192-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27192-6