Abstract

Myanmar amber is famous worldwide for its abundant, exquisite, and diverse fossils (including those of flowers). However, the importance and value of this amber flora are still underappreciated. Here we report a group of well-preserved tiny seeds embedded in Myanmar amber. Many winged seeds are concentrated in a very limited space, revealing a high abundance and a great diversity of angiosperms previously unknown. There are another group of seeds probably from a single plant fruit, but they demonstrate variable wingless morphologies. The variable morphologies of these seeds indicate a previously unknown seed morphological plasticity of the mother plant. The common feature of all these seeds is their tiny size. The present discovery reflects that, during their mid-Cretaceous radiation, at least some taxa adopted a strategy similar to that of extant orchids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Angiosperms are the single largest group in the plant kingdom, including over 261,000 species (APG, 2025)1. However, botanists currently know little about the early history and evolution of angiosperms. The so-called sudden occurrence of angiosperms, once termed the “abominable mystery”, was actually a radiation of angiosperms (especially eudicots) in the Mid-Cretaceous2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Amber preservation is a superior mode for fossil organisms, it has been a focus of studies in palaeontology18,19,20,21. Although Myanmar amber of the Mid-Cretaceous has yielded numerous fossil plants (including at least 31 angiosperms or their flowers)2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,21,22,23, the radiation of angiosperms in the Mid-Cretaceous is poorly understood. Due to their size and beauty, flowers and angiosperms are frequently reported from this fossil lagerstätte2,3,12,13,22, but tiny bodies including seeds are usually ignored. To balance the view on the flora, here we document numerous tiny winged and wingless seeds of various morphologies concentrated in a limited space of Myanmar amber, which is dated as early Cenomanian (98.79 Ma5,10,11,14,17). The concentration of these diverse seeds indicates that angiosperms were abundant and diverse in North Myanmar during the Mid-Cretaceous.

Our samples (PB206074, PB206075) were collected from the Noije Bum 2001 Summit Site, Hukawng Valley, Kachin, Myanmar (26˚20´N, 96˚36´E). Previous paleontological works suggest an early Cenomanian, Cretaceous (98.79 Ma5,10,13,17) age for our samples. The samples were ground, polished, and finally cut and polished as thin sections, for better observation and imaging. The observations and photographs were made with a Nikon SMZ1500, a Zeiss Zoom.V16, a Zeiss Axio Zoom V16, and a Zeiss Lab.A1 microscope at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Nanjing, China. All the figures were organized for publication in Photoshop 7.0.

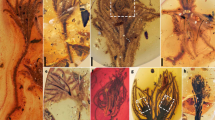

Two blocks of Myanmar amber were studied (Figs. 1, 2 and 3, S1). The amber blocks are transparent, and brownish in color, with various plant inclusions (Figs. 1a-l, 2a-u and 3a-d, S1). The current paper focuses on tiny propagules in amber blocks (Figs. 1a-l, 2a-u and 3a-d, S1). In a triangular-round block, which is 3 cm long, 2.5 cm wide, and approximately 1 cm thick, there are various plant inclusions (Fig. 1a). There are 33 propagule individuals of 14 Morphotypes (Type I ~ XIV) recognized in the block (Figs. 1a-l and 2a-u). Among them, 28 propagule individuals of 11 Morphotypes (Type I ~ VII, X ~ XIII, XIV) (Figs. 1c and 2a-u) are concentrated in a slice less than 80 mm3 (Fig. 1b). In addition to their variations in morphology, the propagules vary greatly in their dimensions, ranging from 30 to 260 μm in length and 15 to 210 μm in width (Figs. 1c-l and 2a-u).

Another oval-shaped block of amber measures 19.6 mm long, 15.5 mm wide, and less than 10 mm thick (Fig. S1). In the block, there are at least five capsules and other inclusions (Fig. S1). Notably, a group of propagules (Type XV), including at least 66 individuals, are concentrated in an area of less than 1 mm2 (Fig. 3a). These propagules are all wingless, but vary in size and morphology (Figs. 3b-c). Some of them are elongated and rounded, measuring 43 ~ 55 μm long and 21 ~ 27 μm wide, whereas most others are rectangular in shape, measuring 34 ~ 43 μm long and 28 ~ 39 μm wide (Figs. 3a-d, S1).

For detailed description, see the supplementary file.

Amber preservation is a superior preservation mode for fossil plants, since such preserved fossils are secluded in amber in three dimensions and are immune to most diagenetic influence during fossilization. This is why many palaeontologists favour plant fossils preserved in ambers2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,16,23. Myanmar amber has previously yielded various fossil plants2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,22, but these are usually preserved separately in different blocks. Therefore, they are good proxies of the diversity of plants (especially angiosperms) in the Cenomanian (Mid-Cretaceous) in Myanmar. However, the abundance and propagules of these plants are poorly understood, thus the current understanding of angiosperms during this special period is limited. Our findings in two blocks of Myanmar amber apparently fill this knowledge gap and shed new light on this important but poorly understood time period for the evolution of angiosperms.

The history of seed plants can be dated back to the Late Devonian (over 360 Ma ago)24. The morphology of seeds varies greatly among different morphotypes of seed plants. For example, the largest extant seeds are those of Lodoicea maldivica (Arecaceae, angiosperms), which measures up to 50 cm long and 30 cm wide, and a single seed may be up to 43 kg in weight25. The smallest seeds also occur in angiosperms, for example, the dust seeds of orchids may be only 50 μm long, and their minimal weight may be as light as 24 µg (Table 1)26. Compared with those of angiosperms, the contrast among the seeds of gymnosperms is less drastic. The largest seeds in the Mesozoic (Dinospermum kelameiliensis)27 and Palaeozoic (Pachytesta gigantea)28 both are over 10 cm long, whereas their dwarf peers in gymnosperms are greater than 1 mm in length24. Compared with the dimensions of seeds in known seed plants, the dimensions of the propagules reported here (< 0.3 mm in length, Figs. 1, 2 and 3, S1) are apparently much smaller than those of fossil and extant gymnosperms. Therefore, we exclude gymnosperms from our following consideration.

Various inclusions, such as anthers, pollen grains, insects, and microorganisms have been reported from amber all over the world18,20,21,22. Some microorganisms, especially those reported by Girard et al18., may appear similar to our morphotypes. For example, Morphotype 6 and 7 in Fig. 2r and u may appear similar to “three-celled Myrmecia-like green alga” in Fig. 2g of Girard et al.18 in general configuration. However, detailed analysis indicates that these two are distinct in sizes: while the “three-celled Myrmecia-like green alga” is less than 20 μm in length, Morphotype 6 and 7 are at least 150 μm in length, in addition to their difference in presence of a dark body in Morphotype 6 and 7 and its complete lack in “Myrmecia-like green alga”. Girard et al. appear to be the pioneers in paying close attention to microorganisms in amber, and we hope this work will further underscore this frequently ignored aspect of amber biota.

Despite their great morphological variation, a common feature of the propagules embedded in PB206074 (Figs. 1d-l and 2a-r and t-u) is that most of them include a body of dense organic material attached to a wing of variable morphology. This unique morphology implies that their dispersal relies on wind rather than animal vectors. At least these angiosperms appear to have not yet established their ecological ties with contemporary animals, which might be derived during later evolution (it is noteworthy that roach pollination has been documented in Cretaceous Myanmar and Lebanese ambers19). Notably, these tiny propagules resemble the dust seeds observed in orchids26,29, which are interpreted as highly derived in the APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) system30. If later studies may confirm the phylogenetic relationship between our fossils and orchids, the current interpretation of orchid history would need revision. On the basis of currently available data and ignoring the possible relationship among these groups, the wing morphology of these propagules suggests that some Mid-Cretaceous angiosperms have adopted a strategy that was more or less similar to that of extant orchids in their propagule dispersal. This dispersal strategy of angiosperms has never been heard before for angiosperms in the Mid-Cretaceous.

A common feature is that all the seeds have no well-defined seed coat, which is more likely to be preserved in fossils. Although unusual-appearing, such a lack of seed coat is frequently observed in orchids26,29,31,32. This feature is in line with the above discussed presence of a wing for the seeds. Both of these features suggest an affinity to Orchidaceae. As shown in Table 1, although most morphotypes documented here have wing-like structures (which are helpful for their floating in the air) and lack well-developed seed coat, they lack the usually linear seed form frequently seen in extant orchids. Therefore we prefer not to relate them to orchids. Instead, we tend to think that their dispersal was carried out in a way more or less similar to that in Orchidaceae. This is a new ecological aspect of Mid-Cretaceous angiosperms, which was previously unknown.

A conspicuous phenomenon of these propagules is that at least 25 propagule individuals of 14 Morphotypes (Figs. 1c and 2a-u) are concentrated in a slice of amber less than 1.5 mm thick and less than 80 mm3 in volume (Fig. 1b). This high diversity and concentration of propagules in limited space implies that the diversity of local angiosperms is greater than what previous studies have implied2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,16,23. This implication for the first time highlights the diversity of angiosperms in local area. Among these propagules, some morphotypes occur at greater frequencies, whereas others occur at much lower frequencies. This variation in occurrence frequency depends on the number of individual plants and their seed-setting, It may also be affected by differences in the production of plant seeds or pollen. Although our current data apparently cannot provide comprehensive information on the individual number and seed-setting of the concerned morphotypes, the possibility of future studies doing so cannot be excluded completely.

Another observation is that propagules of the same morphotype may be of distinct shapes (Figs. 3a-d, S1). While most of the propagules are rectangular in shape (Fig. 3d), some of them are round (Fig. 3c). This distinction may be attributed to the abortion of some propagules (early ovules may be round and different from mature seeds), or to the morphological plasticity of this angiosperm. The rectangular shape of most seeds in Figs. 3a-d is hitherto unheard for fossil angiosperms and is at most rarely seen in extant angiosperms33. For example, Chamaecrista fasciculata and C. nictitans (Fabaceae) have rectangular-shaped seeds arranged in a row in pea pods, more or less similar to the propagules seen in Figs. 3a-d. However, it should be noted that the seeds of these fabaceous plants are more than 2 mm in any dimension, which is distinct from the seeds/propagules seen in present Myanmar amber (Figs. 3a-d). According to currently available data, the seeds/propagules in Figs. 3a-d and S1 represent the smallest rectangular-shaped seeds throughout the history of plants.

The concentration of more than 66 individuals in a limited area (less than 1 mm2) and the absence of any other plant inclusions imply that these propagules were formerly in a single fruit and that a fruit of the angiosperm may yield numerous seeds. This is thus far the greatest yield of seeds per fruit for fossil angiosperms. In addition to their unique shapes and tiny sizes (discussed above), these fossil seeds, for the first time, indicate that there are so many seeds per fruit in a fossil plant. This number distinguishes the mother plant from all known gymnosperms (fossil and extant), highlighting its resemblance and affinity to some angiosperms (e.g., Orchidaceae). The bottom line is that some Mid-Cretaceous angiosperms have adopted a survival strategy similar to that of orchids, the history of such a strategy in angiosperms is much older than formerly assumed, and the orchid survival strategy apparently is not newly derived.

Conclusions

The propagules/seeds exquisitely preserved in Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber are highly abundant, diverse, and variable. Although the fossil plants in Myanmar amber have been repeatedly documented, microecological aspects of Mid-Cretaceous fossil angiosperms, which used to be considered pioneer angiosperms, were previously unrevealed. Our new observations and data provide the raw materials to enhance and deepen our understanding of early angiosperms, and to refine the picture of plant evolution during the radiation of angiosperms in the Mid-Cretaceous.

Ethics approval

This study includes fossil specimens that comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation The amber fossils in this study were collected from the Hukawng Valley in Kachin State, northern Myanmar, near the village of Noije Bum (26°20′N, 96°36′E), located approximately 18 km southwest of Tanai Township. Research on Burmese amber has a century-long history, with hundreds of related studies published worldwide to date. It is permanently curated at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS), Nanjing, China, under the catalog number PB206074.

Consent to participate

No ethical approval or consent was necessary for this research, as it did not involve endangered or protected plant species. Specimens support open access, and the identification of specimens was completed by the corresponding author of this article.

A Myanmar amber and its various inclusions. d-l are from the region outside of the quadrilateral in a. PB206074. a. Myanmar block. Scale bar = 10 mm. b. A small piece of amber with various inclusions (including three capsules), enlarged from the quadrilateral in a. Some of the winged seeds are labelled with triangles. Scale bar = 1 mm. c. Two different inclusions in proximity. Scale bar = 50 μm. d. Three different inclusions in proximity. Scale bar = 0.2 mm. e. Two different inclusions in proximity. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. f. A winged seed with an eccentric wing. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. g. A seed completely surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. h. A seed attached to the base part of a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. i. A three-winged seed enlarged from Fig. 1c. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. j. A seed completely surrounded by a wing with an irregular margin. Scale bar = 50 μm. k. A seed completely surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. l. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Various seeds in a piece of Myanmar amber shown in Fig. 1b. PB206075. a. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 10 μm. b. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. c. Two seeds with funiculi, enlarged from Fig. 1c. Scale bar = 50 μm. d. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 20 μm. e. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. f. A seed with three lobes of a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. g. A seed completely surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. h. A seed attached to a bilobate wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. i. A seed attached to an eccentric wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. j. A seed completely surrounded by a round-triangular wing. Scale bar = 20 μm. k. A seed completely surrounded by an eccentric wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. l. A seed (?) with a wing. Scale bar = 20 μm. m. A seed attached to a bilobate wing. Scale bar = 20 μm. n. A seed attached to a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. o. A seed almost completely surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. p. A seed half-surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. q. A seed surrounded by a wing. Scale bar = 50 μm. r. A seed surrounded by two wings with wavy margins. Scale bar = 50 μm. s. A germinating pollen grain. Scale bar = 10 μm. t. A seed attached to a wing by a stalk. Scale bar = 50 μm. u. Three or four adherent seeds. Scale bar = 50 μm.

A group of seeds with variable morphology in a piece of Myanmar amber. PB206075. a. A group of seeds in proximity, enlarged from the rectangle in Fig. S1. Scale bar = 0.2 mm. b. Detailed view of the rectangle in Fig. 3a. Scale bar = 0.2 mm. c. Twelve seeds in proximity but of different forms (round or rectangular). Scale bar = 0.1 mm. d. Two rectangular seeds. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Data availability

All data are reported in this paper.

References

Crepet, W. L. & Niklas, K. J. Darwin’s second abominable mystery: why are there so many angiosperm species? Am. J. Bot. 96, 366–381 (2009).

Liu, Z. J., Huang, D., Cai, C. & Wang, X. The core eudicot boom registered in Myanmar amber. Sci. Rep. 8, 16765. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35100-4 (2018).

Poinar, G. O. & Chambers, K. L. Palaeoanthella Huangii gen. And sp. nov., an early cretaceous flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. Sida 21, 2087–2092 (2005).

Poinar, G. Jr, Lambert, J. B. & Wu, Y. Araucarian source of fossiliferous Burmese amber: spectroscopic and anatomical evidence. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 1, 449–455 (2007).

Poinar, G. O. Jr., Buckley, R. & Chen, H. A primitive mid-Cretaceous angiosperm flower, Antiquifloris latifibris gen. AND sp. nov., in Myanmar amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 10, 155–162 (2016).

Poinar, G. O. Jr., Chambers, K. & Buckley, R. An early cretaceous angiosperm fossil of possible significance in Rosid floral diversification. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2, 1183–1192 (2008).

Poinar, G. O. Jr., Chambers, K. L. & Buckley, R. Eoëpigynia burmensis gen. And sp. nov., an early cretaceous eudicot flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 1, 91–96 (2007).

Poinar, G. O. Jr., Chambers, K. L. & Wunderlich, J. Micropetasos, a new genus of angiosperms from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 7, 745–750 (2013).

Chambers, K. L., Poinar, G. O. Jr. & Buckley, R. Tropidogyne, a new genus of Early Cretaceous Eudicots (Angiospermae) from Burmese amber. Novon 20, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.3417/2008039 (2010).

Xing, L. et al. A mid-Cretaceous embryonic-to-neonate snake in amber from Myanmar. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5042. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat5042 (2018).

Poinar, G. Burmese amber: evidence of Gondwanan origin and Cretaceous dispersion. Hist. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2018.1446531 (2018).

Poinar, G. O., Chambers, K. L. & Wunderlich, J. Micropetasos, a new genus of angiosperms from midcretaceous Burmese amber. Palaeodivers. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 2 (2013).

Poinar, G. O. J. & Chambers, K. L. Tropidogyne pentaptera, sp. nov., a new mid-Cretaceous fossil angiosperm flower in Burmese amber. Palaeodiversity 10, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.18476/pale.v10.a10 (2017).

Poinar, G. Jr A mid-Cretaceous Lauraceae flower, Cascolaurus burmitis gen. And sp. nov., in Myanmar amber. Cretac. Res. 71, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2016.11.015 (2017).

Poinar, G. O. Jr & Chambers, K. L. Palaeoanthella Huangii gen. And sp. nov., an early cretaceous flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. Sida 21, 2087–2092 (2005).

Shi, C. et al. Fire-prone Rhamnaceae with South African affinities in cretaceous Myanmar amber. Nat. Plants. 8, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-01091-w (2022).

Shi, G. et al. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U–Pb dating of zircons. Cretac. Res. 37, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.014 (2012). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Girard, V. et al. Taphonomy and palaeoecology of mid-Cretaceous amber-preserved microorganisms from Southwestern France. Geodiversitas 31, 153–162 (2009).

Sendi, H. et al. Roach nectarivory, gymnosperm and earliest flower pollination evidence from cretaceous ambers. Biologia 75, 1613–1630. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-019-00412-x (2020).

Schmidt, A. R. & Dilcher, D. L. Aquatic organisms as amber inclusions and examples from a modern swamp forest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707949104 (2007).

Ross, A. J. Complete checklist of Burmese (Myanmar) amber taxa 2023. Mesozoic 1, 21–57 (2024).

Poinar, G. Flowers in Amber, Vol. 215 (Springer, 2022).

Schmidt, A. R. et al. Selaginella was hyperdiverse already in the cretaceous. New Phytol. 228, 1176–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16600 (2020).

Linkies, A., Graeber, K., Knight, C. & Leubner-Metzger, G. The evolution of seeds. New Phytol. 186, 817–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03249.x (2010).

Bellot, S. et al. On the origin of giant seeds: the macroevolution of the double coconut (Lodoicea maldivica) and its relatives (Borasseae, Arecaceae). New Phytol. 228, 1134–1148. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16750 (2020).

Barthlott, W., Groβe-Veldmann, B. & Korotkova, N. Orchid Seed Diversity: A Scanning Electron Microscopy Survey, 211 (Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem, 2014).

Lu, H., Zhou, X., Hou, Y., Yin, P. & Wang, X. The biggest seed from the mesozoic and its evolutionary implications. Int. J. Health Sci. 8, 198–208 (2024).

Brongniart, A. Recherches Sur Les Graines Fossils silicifiées (Imprimerie Nationale, 1881).

Arditti, J. & Ghani, A. K. A. Numerical and physical properties of Orchid seeds and their biological implications. New Phytol. 145, 367–421 (2000).

APG. APG IV. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20 (2016).

Nakanishi, H. Seed morphology and dispersibility of orchids in warm temperate Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica Et Geobotanica. 73, 19–33. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.202114 (2022).

Cameron, K. & Chase, M. Seed morphology of the vanilloid orchids. Lindleyana 13, 148–169 (1998).

Martin, A. C. & Barkley, W. D. Seed Identification Manual, 221 (Blackburn, 2000).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Ms. Jingjing Tang for help with microscopy. We appreciate Dr. Dany Azar for his exquisite preparation of specimens. The hard work of two reviewers has left a deep impression on us, and we would like to express our sincere gratitude to them here.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF0807601) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42288201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: X.W. designed the research project, and drafted the manuscript. W.H. collected the specimens. All authors have analyzed the data, modified, finalized and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, W., Wang, X. Fossil evidence of orchid-like dust seeds in Myanmar amber featuring early angiosperm radiation. Sci Rep 15, 43177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27211-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27211-6