Abstract

Acute kidney injury is a common and critical complication in patients with community-acquired pneumonia who are admitted to intensive care units, substantially increasing their risk of short-term mortality. To enhance early clinical decision-making, we developed and validated multiple machine learning-based survival models to predict 28-day mortality using data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC IV and MIMIC III databases). Five models were evaluated: Random Survival Forests, Gradient Boosting Machine, Lasso-Cox, CoxBoost, and Survival-SVM. Among these, the CoxBoost model demonstrated superior predictive performance with an AUC of 0.737in internal validation cohort and an AUC of 0.671 in external validation cohort, outperforming established clinical scoring systems. Decision curve analysis indicated high net benefit across a clinically relevant range of predicted risks. Key predictive features identified by model interpretation included age, vasopressor use, NSAIDs use, hemoglobin level, hypertension, and blood urea nitrogen. To improve practical application, we developed a web application that allows for individualized, real-time mortality risk prediction at the bedside. This tool may help identify high-risk patients earlier and support timely, personalized treatment strategies in critical care environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) frequently occurs in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), with incidence rates ranging between 22.5% and 46%1,2. The coexistence of AKI in CAP significantly complicates clinical management, often necessitating advanced interventions such as mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and renal replacement therapy3. These interventions reflected the greater severity of illness and the increased risk of poor outcomes in this patient population. CAP patients who develop AKI exhibit significantly higher mortality rates than those without AKI. A large cohort study reported an in-hospital mortality rate of 23.5% in CAP patients with AKI, compared to 4.9% in those without AKI1. Longitudinal studies further confirmed the impact of AKI on CAP prognosis, demonstrating higher mortality rates at hospital discharge (11% vs. 1.3%), 90 days (24% vs. 9.8%), and 1 year (36.3% vs. 20.1%) 3. Moreover, AKI severity correlates with increased mortality, with 30-day mortality rising from 15.2% to 47.3% across different AKI stages1. Given the significant impact of AKI on mortality in CAP patients, early identification of high-risk individuals is essential for timely intervention.

Despite the increasing recognition of AKI’s impact on CAP outcomes, existing predictive models remain inadequate. Several models have been developed to estimate mortality risk in AKI or other critically ill populations4,5. However, these models may not adequately capture the interaction between pneumonia severity and renal dysfunction, resulting in suboptimal predictive accuracy in CAP patients with AKI. Existing ICU scoring systems, such as the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and the Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS)6,7, were not originally designed to assess mortality risk in CAP patients with AKI. To date, no dedicated model has been developed for predicting short-term mortality specifically in CAP patients with AKI. An accurate predictive model for short-term mortality in CAP patients with AKI would facilitate early clinical decision-making, improve risk stratification, and enhance patient outcomes.

Machine learning (ML)-based prediction models offer several advantages over traditional mortality risk models. ML models, including Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and Extreme Gradient Boosting, leveraged advanced algorithms to analyze large datasets and uncover complex relationships, often achieving superior predictive accuracy8,9. Additionally, ML models exhibited enhanced capabilities in complex data processing, effectively incorporating numerous variables and interactions, as demonstrated in sepsis mortality prediction10.

This study aimed to develop and validate an ML-based survival model to predict 28-day mortality in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI. We compared multiple survival analysis models, including CoxBoost, Random Survival Forests (RSF), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Lasso-Cox Regression, and Survival-SVM, and developed a web-based prediction tool for real-time risk estimation and individualized patient management.

Methods

Study design, data Source, and outcome definition

This study was a retrospective cohort analysis utilizing the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database, a publicly available dataset containing de-identified health records of critically ill patients admitted to ICUs at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The use of the MIMIC-IV database for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). As the database contains only de-identified patient information, the requirement for informed consent was waived. The first author completed the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) program and was granted access to the database (Record ID: 64595863). All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the MIMIC-IV data use agreement and complied with relevant guidelines and regulations, including those related to the ethical use of de-identified human data.

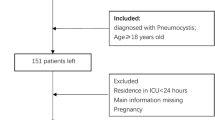

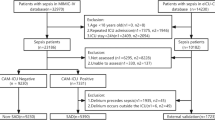

Flow chart of the study design was shown in Fig. 1. Patients diagnosed with CAP were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes. The inclusion criteria encompassed adult patients (≥ 18 and ≤ 100 years) with CAP who subsequently developed AKI before the first 24 h in ICU. AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria11, which includes: an increase in serum creatinine (SCr) by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 µmol/L) within 48 h, or an increase in SCr to ≥ 1.5 times the baseline value within the prior 7 days, or a urine output of < 0.5 mL/kg/h for at least 6 h. Patients with CAP were excluded if they met any of the following conditions: (1) did not develop AKI or develop AKI after the first 24 h in ICU; (2) had a history of chronic kidney disease stage 5 (CKD5) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD); (3) length of stay in ICU < 24 h; (4) Non-first ICU stay.

Flow chart of the study design. CAP, Community-Acquired Pneumonia; AKI, Acute Kidney Injury; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; CKD5, Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 5; ESRD, End-Stage Renal Disease; AUC, Area Under the Curve; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic; DCA, Decision Curve Analysis; KM Analysis, Kaplan-Meier Analysis; RSF, Random Survival Forests; GBM, Gradient Boosting Machine; LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; Cox, Cox Regression; SVM, Support Vector Machine.

Clinical variables extracted within the first 24 h of ICU admission included demographics (age, gender, race), vital signs (24 h-urine output, height, weight, heart rate, SBP, DBP, MBP, respiratory rate, body temperature), laboratory tests (hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets, WBC, basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, CRP, albumin, globulin, total protein, ALT, ALP, AST, total bilirubin, GGT, LDH, BUN, creatinine, anion gap, calcium, chloride, glucose, sodium, potassium, D-dimer, fibrinogen, INR, PT, PTT, CK, CK-MB, lactate, pH, SO2, PO2, PCO2, PaO2-FiO2 ratio, Base excess, Bicarbonate), comorbidities (myocardial infarct, Congestive heart failure, Cerebrovascular disease, Chronic pulmonary disease, Liver disease, Diabetes, Renal disease, Malignant cancer, Hypertension, Sepsis), clinical scores (Charlson comorbidity index, SOFA, APS III, GCS, LODS, OASIS, SIRS, APACHE II, SAPS II, CURB-65) and interventions (antibiotics, ventilation, NSAIDs, vasopressor, CRRT). The primary outcome of this study was 28-day all-cause mortality, defined as death occurring within 28 days from ICU admission. Survival time was calculated from the date of ICU admission to the date of death or last follow-up. Patients who survived beyond 28 days were censored at 28 days.

Data preprocessing and feature selection

Prior to analysis, data preprocessing was performed to address missing values and ensure data integrity. Variables with more than 25% missing values were excluded from further analysis, seen in Supplementary Table S1. For variables with ≤ 25% missing values, missing data were imputed using the missForest imputation method.

A systematic feature selection approach was employed to identify the most relevant predictors for survival modeling. First, baseline characteristics were compared between survivors and non-survivors to identify variables significantly associated with 28-day mortality. Next, a Spearman correlation analysis was performed among all candidate variables to assess multicollinearity, and variables with a correlation coefficient > 0.6 were considered closely collinear (seen in Supplementary Table S2).

Among collinear pairs, the variable with the weaker association with the primary outcome was removed. Subsequently, univariate Cox regression was conducted to examine the relationship between each remaining variable and survival. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent predictors of mortality. Statistically significant variables from the multivariate Cox model were selected as final features for machine learning model development.

Model development, validation, evaluation and interpretation

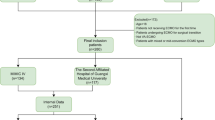

To develop predictive models for 28-day mortality, five survival analysis models were implemented: Random Survival Forests (RSF), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Lasso-Cox Regression, CoxBoost Regression, and Support Vector Machine for Survival Analysis (Survival-SVM), cross-validation was performed during hyperparameter tuning to prevent overfitting. The dataset was randomly split into a training set (70%) for model development and a testing set (30%) for model validation. An independent cohort from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III) database was extracted for external validation. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the MIMIC-IV cohort were used to identify patients with CAP complicated by AKI in MIMIC-III.

The performance of each model was assessed using multiple metrics. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the models’ ability to distinguish between survivors and non-survivors. Concordance Index (C-index) was calculated to evaluate the models’ discrimination ability in the context of time-to-event survival data. Calibration plots were used to assess model reliability. Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) was performed to determine the net clinical benefit of each model across a range of threshold probabilities. The best model was used to stratify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on predicted survival probabilities. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for the stratified groups, and log-rank tests were conducted to evaluate differences in survival distributions.

To enhance model interpretability, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was conducted. A Shiny-based application was developed for real-time 28-day mortality prediction using the model with best performance.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were conducted using R software (version 4.4.2). Continuous variables were summarized as mean (SD) or median (IQR), depending on the data distribution. Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Independent t-tests were used for normally distributed continuous variables, while Mann-Whitney U tests were applied to non-normally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with CAP and AKI in survival and non-survival groups

A total of 1795 ICU-admitted patients with CAP and AKI were included in the study, among whom 453 died within 28 days. The baseline characteristics of the study population, stratified by survival status, were summarized in the Supplementary Table S3.

Compared to survivors, non-survivors were older and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, renal disease, malignancy, hypertension, and sepsis. Additionally, non-survivors exhibited lower wight, higher respiratory rates and heart rates. Laboratory findings indicated that non-survivors had lower hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets, and higher WBC, ALP, anion gap, BUN, creatinine, INR, PT, PTT. Regarding clinical severity scores, non-survivors had significantly higher Charlson comorbidity index, SOFA, APS III, LODS, OASIS, SIRS, APACHE II, SAPS II, and CURB-65, indicating greater disease burden and organ dysfunction. In terms of treatment interventions, non-survivors were more likely to receive CRRT, vasoactive support, and less use of NSAIDs.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis

To identify independent risk factors associated with 28-day mortality in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed (Table 1). In univariate analysis, existence of myocardial infarct, congestive heart failure, liver disease, renal disease, malignant cancer, hypertension, higher age, heart rate, WBC, BUN, anion gap, PT, PTT, and use of vasopressor were identified as high-risk factors. While, use of NSAIDs, higher hemoglobin and weight were associated with a reduced risk.

After adjusting for potential confounders, multivariate Cox regression analysis identified several independent risk factors for 28-day mortality, including increased age (HR = 1.02, 95%CI: 1.01–1.03, P < 0.001), elevated heart rate (HR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00–1.01.00.01, P = 0.001), history of myocardial infarct (HR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.03–1.71, P = 0.027), liver disease (HR = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.16–1.96, P = 0.002), malignant cancer (HR = 1.44, 95%CI: 1.12–1.83, P = 0.004), hypertension (HR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.02–1.59, P = 0.033), higher BUN levels (HR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00–1.01.00.01, P < 0.001), elevated ALP (HR = 1.00, 95%CI: 1.00–1.00, P < 0.001), prolonged PTT (HR = 1.00, 95%CI: 1.00–1.01.00.01, P = 0.002), reduced urine output (HR = 1.00, 95%CI: 1.00–1.00, P = 0.036), platelet count (HR = 1.00, 95%CI: 1.00–1.00, P < 0.001), and vasopressor use (HR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.34–2.05, P < 0.001), while protective factors included NSAIDs administration (HR = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.55–0.84, P < 0.001), higher weight (HR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.99–1.00.99.00, P = 0.021), and elevated hemoglobin levels (HR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.88–0.96, P < 0.001).

Model development, evaluation, and clinical application

To develop a predictive model for 28-day mortality, five survival models were trained and validated, including RSF, GBM, Lasso-Cox Regression, CoxBoost Regression, and Survival-SVM. Model discrimination ability was evaluated using ROC curves and the C-index (Fig. 2). The ROC curves (Fig. 2a) showed that CoxBoost had the highest discriminatory performance, with AUC values of 0.737, followed by Lasso-Cox (AUC = 0.736), RSF (AUC = 0.723) and GBM (AUC = 0.718), while Survival-SVM had significantly lower performance (AUC = 0.593). The time-dependent C-index analysis (Fig. 2b) indicated that CoxBoost, Lasso-Cox, GBM, and RSF showed similar trajectory. Conversely, the Survival-SVM exhibited a poor value of C-index along with time.

Calibration plots (Fig. 3) demonstrated that CoxBoost and Lasso-Cox exhibited best calibration performance, with predicted survival probabilities closely aligning with observed outcomes across all risk levels. In contrast, Survival-SVM demonstrated significant miscalibration.

To evaluate clinical applicability, DCA and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed. DCA plots (Fig. 4) showed that CoxBoost provided the highest net clinical benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities (5%−65%), outperforming all other models. GBM and RSF also showed relatively lower net clinical benefit in a narrow range of threshold. However, Lasso-Cox and Survival-SVM didn’t show clinical net benefits at all.

CoxBoost was ultimately selected as the best model due to its strong overall performance. KM survival curves (Fig. 5) further confirmed the excellent stratification performance of CoxBoost to distinct high-risk from low-risk groups (p < 0.0001).

To further assess the predictive performance of the CoxBoost model in comparison to traditional ICU prognostic scores, we evaluated the AUC for each scoring system (Fig. 6). The CoxBoost model significantly outperformed established ICU prognostic scores such as SAPS II (AUC = 0.697, 95% CI: 0.646–0.749), APACHE II (AUC = 0.684, 95% CI: 0.634–0.735), Charlson Comorbidity Index (AUC = 0.678, 95% CI: 0.627–0.729), LODS (AUC = 0.675, 95% CI: 0.621–0.730), APS III (AUC = 0.670, 95% CI: 0.617–0.723), SOFA (AUC = 0.646, 95% CI: 0.590–0.701), OASIS (AUC = 0.644, 95% CI: 0.589–0.698), and CURB-65 (AUC = 0.644, 95% CI: 0.592–0.696). Notably, CoxBoost exhibited a greater ability to distinguish high-risk patients than CURB-65 and OASIS, which were commonly used for pneumonia severity assessment. These findings suggested that CoxBoost model may provide enhanced risk stratification beyond traditional clinical scoring systems, potentially aiding in early decision-making and targeted interventions for ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI.

A total of 998 patients with CAP and AKI were identified in the MIMIC-III cohort for external validation, and the baseline characteristics were shown in Supplementary Table S4. As shown in Fig. 7, the CoxBoost model achieved an AUC of 0.671 (95% CI: 0.631–0.710), which outperformed traditional prognostic scores, including SAPS II (AUC = 0.651, 95% CI: 0.611–0.692), APS III (AUC = 0.633, 95% CI: 0.592–0.674), CURB-65 (AUC = 0.607, 95% CI: 0.568–0.646), and others. These findings confirmed the robustness of the CoxBoost model when applied to an independent dataset.

Model interpretation and web application deployment

To enhance the interpretability of the CoxBoost model, SHAP analysis was conducted to assess the contribution of individual features to model predictions (Fig. 8). The feature importance ranking (Fig. 8a) indicated that age, vasopressor use, NSAIDs use, hemoglobin, hypertension, and BUN were the most influential predictors of 28-day mortality, suggesting their crucial roles in patient prognosis. SHAP beeswarm plot (Fig. 8b) further illustrated the direction of impact of these features across the entire patient cohort, showing that age, vasopressor use, hypertension and higher BUN increased mortality risk, while NSAIDs use and higher hemoglobin were associated with reduced risk. SHAP waterfall plot (Fig. 8c) was used to explain how the variables influenced individual outcome. The relationship between single feature and SHAP value was explored in detail using SHAP dependence plots (Supplementary Fig. 1). The model learned strong, near-linear relationships for key continuous variables: mortality risk increased linearly with rising age and BUN levels, and decreased linearly with higher hemoglobin. For binary predictors, the plots clearly show a positive shift in SHAP values when vasoactive support or hypertension was present (value = 1), whereas NSAIDs use resulted in a significant negative shift, visually confirming its role as a protective factor within the model.

SHAP-based feature importance and interpretation for 28-day mortality prediction in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI. (a) Mean SHAP values for feature importance ranking. (b) SHAP beeswarm plot displaying the distribution of SHAP values for each feature. (c) SHAP waterfall plot illustrating individual-level feature contributions.

To facilitate clinical implementation, a Shiny-based web application was developed for real-time 28-day mortality prediction using the CoxBoost model (Fig. 9). The application allowed clinicians to input patient characteristics and received personalized 28-day mortality, survival curves, and individual waterfall plot, aiding in early and personalized intervention strategies. By integrating explainable machine learning with an accessible user interface, this tool bridged the gap between advanced predictive modeling and practical decision-making in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI. The application can be used through the link (https://predicti.shinyapps.io/cap_aki_prediction/).

Discussion

This study developed a machine learning-based CoxBoost survival model to predict 28-day mortality in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI. The model exhibited strong predictive performance across multiple evaluation metrics, surpassing conventional ICU risk scores including SAPS II, APACHE II, APS III, OASIS, and CURB-65. SHAP analysis identified age, vasopressor use, hypertension, and higher BUN as risk factors, while NSAIDs use and higher hemoglobin as the protective factors of 28-day mortality. Furthermore, a web-based tool was implemented, allowing real-time individualized mortality prediction and recognizing most influential factors promoting mortality, assisting clinical decision-making, and supporting early intervention strategies.

Currently, no specialized predictive model exists for assessing short-term mortality risk in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI, emphasizing the novel contribution of this study. Conventional ICU prognostic tools, including SAPS II, APACHE II, CCI, SOFA, APS III, LODS, OASIS, and CURB-65, have been utilized for disease severity and mortality prediction in critically ill populations. A study evaluating these models in sepsis-associated acute respiratory failure reported AUC values of 0.731, 0.755, 0.706, and 0.606 for LODS, APS III, OASIS, and SOFA, respectively, indicating variable predictive performance in critically ill patients12. CCI has been shown to outperform CURB-65 in predicting in-hospital mortality in CAP patients13. SOFA and the dynamics of SOFA were both also a strong predictor of ICU mortality6. SAPS II and APACHE II also exhibited good performance to predict in-hospital mortality of coronary care unit patients14. Compared to these traditional scoring systems, our CoxBoost model demonstrated superior predictive performance, as evidenced by higher AUC in predicting mortality of patients with CAP and AKI. In the meanwhile, the model was convenient to clinical use as all the variables included were common and necessary in ICU.

Beyond its aggregate predictive performance, the clinical acceptance and trustworthiness of a predictive model are critically dependent on the plausibility of the features driving its predictions. The SHAP analysis performed in our study moved beyond a ‘black box’ approach by providing a clear hierarchy and directional impact for each predictor. This allowed for a deeper clinical interrogation of the model’s logic. Age emerged as a key predictor of mortality in our analysis, with advanced age correlating with increased mortality in CAP patients with AKI. This aligns with previous studies, where a progressive rise in mortality risk was observed with advancing age among CAP patients (OR = 1.02)2. Additionally, in cases of contrast-induced nephropathy, age above 75 years has been recognized as an independent predictor of mortality15,16. The heightened mortality risk in elderly patients may stem from physiological aging, multimorbidity, and immune senescence, all of which exacerbate susceptibility to severe infections and fatal outcomes in acute illness.

Hypertension was identified as a risk factor of 28-day mortality in patients with CAP and AKI in our study, which was in coincidence with previous studies. Hypertension may not directly cause death within 28 days, but it likely reflects an underlying vulnerability. Patients with hypertension frequently have coexisting cardiovascular disease, renal impairment, and vascular dysfunction, all of which may exacerbate acute illness and increase susceptibility to poor outcomes when CAP and AKI occur simultaneously. Hypertension itself also was reported as an independent risk factor of in-hospital and 30-day mortality in patients with CAP1. Use of ARBs to control blood pressure was associated with reduced in-hospital mortality of patients with CAP and hypertension17. In addition, hypertension exacerbated renal damage by increasing the pressure load on the kidneys, which can lead to further deterioration of renal function. ACEI/ARBs use was associated with lower all-cause ICU-mortality in patients with AKI18.

Higher hemoglobin was found beneficial to 28-day survival in patients with CAP and AKI in our study. Hemoglobin often reflected the immune and nutritional status. Lower hemoglobin may indicate malnutrition and immune disorders, which decreased the capacity to prevent and sweep away pathogens. While it didn’t seem the more, the better. In critically ill patients with sepsis, hemoglobin showed nonlinear association with in-hospital mortality with a threshold on 10.2 g/dL19. Another study reported that both lower (men: <13.0 g/dL; women: <11.0 g/dL) and higher (men: ≥16.0 g/dL; women: ≥14.0 g/dL) hemoglobin were associated with increased mortality, and with lower hemoglobin at higher mortality risk than those with higher hemoglobin. Fortunately, it also showed that improves hemoglobin levels decreased the mortality, compared with continuous lower levels of hemoglobin20. It provided beneficial advice for physicians to maintain normal levels of hemoglobin of patients.

NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase, reducing prostaglandin synthesis, which can impair renal perfusion and exacerbate renal burden, thereby contributing to AKI development. Research has identified NSAIDs use as an independent risk factor for AKI, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect, where higher doses correlate with increased AKI risk21,22. However, some studies suggest that early NSAID administration may not necessarily worsen renal function in specific patient populations, such as critically ill trauma patients23. A previous study reported that ibuprofen use significantly reduced 30-day mortality in patients with hypothermic sepsis24. Therefore, the use of NSAIDs in CAP patients remains controversial in clinical practice. Interestingly, in our study, NSAIDs was observed as a protective factor for survival. We hypothesized that the survival benefit of NSAIDs may be attributed to their properties to reduce inflammation and pain, though the precise mechanisms require further investigation in future studies. Studies also mentioned that NSAIDs use has been associated with both positive and negative outcomes dependent on the timepoint of administration. For instance, NSAIDs treatment within 24 h before AKI onset was linked to decreased 14-day mortality25. Consequently, after considering the dose and time of NSAIDs use, it may be a potential treatment to reduce mortality of CAP patients with AKI according our model.

BUN, a marker of renal function, is often elevated in AKI and can serve as an indicator of disease severity and prognosis. BUN levels usually increase with the progression of AKI stages. As mentioned above, higher AKI stages were associated with increased mortality in CAP patients with AKI1. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that elevated BUN levels are correlated with increased mortality in this patient population. Studies have found the association between BUN or indicators containing BUN and prognosis of critically ill patients. Studies reported that elevated BUN levels have been associated with increased mortality in various conditions, including cirrhosis and acute pancreatitis26,27. The BUN/creatinine ratio (BCR) has been shown to predict mortality in critically ill patients with AKI. Patients with a BCR > 20 showed more severe condition and higher mortality28. BUN/serum albumin ratio (BAR) was also identified as an independent risk factor for mortality of AKI patients and was associated with higher 28-day mortality when the value > 4.32. All of these studies suggested the potential as a prognostic marker in CAP complicated by AKI of both BUN and indicators containing BUN.

The pathophysiology of AKI in CAP patients was often associated with hemodynamic alterations, microcirculatory dysfunction, and inflammatory responses, which contributed to the high mortality rate29. Vasopressor, such as norepinephrine, are commonly used to manage hemodynamic instability in these critically ill patients. However, it was reported that their use was associated with increased mortality in patients with AKI requiring dialysis, particularly when used in higher doses30,31. Additionally, the Vasoactive-Inotropic Score is a tool used to quantify the degree of cardiovascular support required by patients. Higher VIS values have been associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients, including those with AKI32,33. On one hand, those patients who needed the treatment often suffered more severe conditions and worse prognosis. On the other hand, these medications acted by inducing vasoconstriction and increasing cardiac output to maintain blood pressure. However, they may also reduce renal perfusion, leading to renal ischemia and exacerbating AKI severity. Therefore, the administration of vasoactive agents reflected the severity of the patient’s condition and was associated with poorer prognosis.

Our study presented the first ML-based predictive model specifically designed for short-term mortality risk assessment in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI, addressing a critical gap in existing prognostic tools. Despite the value in research and benchmarking of conventional ICU scoring systems, they were seldom used in daily ICU practice to directly guide bedside treatment decisions. Compared with these traditional scoring systems, our CoxBoost model not only demonstrated superior predictive performance, as evidenced by higher AUC values in CAP patients with AKI, but also holds greater potential for actionable integration into ICU workflows. High-risk patients identified by our model can trigger a KDIGO-concordant kidney-protective bundle, including early hemodynamic optimization, strict urine output and serum creatine surveillance, and avoidance or dose adjustment of nephrotoxins, which has been associated with reduced progression of AKI and fewer major adverse kidney events34,35. Earlier nephrology consultation, for example within 24 h of ICU admission, has also been linked to lower in-hospital mortality and shorter length of stay in critically ill AKI populations36,37. Risk information further supports proactive preparation for renal replacement therapy (RRT), for a multinational, randomized, controlled trial found patients with AKI who received accelerated RRT within 12 h were at lower risk of 90-day mortality than those who received standard RRT with specific indications38. Moreover, high-risk labeling can prioritize intensified monitoring such as higher nurse-to-patient ratios, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, bedside ultrasound for fluid responsiveness, and more frequent laboratory and urine output assessments, measures associated with improved AKI detection and outcomes39. Finally, for the sickest patients, early goals-of-care or palliative consultation has been shown to improve communication, reduce non-beneficial interventions, and optimize ICU resource utilization40,41. In this way, our model provides a framework for linking mortality risk prediction to concrete escalation pathways in ICU settings, thereby facilitating timely and personalized management strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, although we conducted external validation using the MIMIC-III database, the model’s AUC was lower than in the internal validation but still outperformed conventional ICU scores, suggesting that it retains prognostic value in an independent cohort. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the need for further refinement and multicenter validation to optimize performance and ensure broader applicability. Additionally, our analysis was constrained by missing data, as some clinically relevant variables were unavailable or incomplete in the dataset. This may have influenced model performance. Future studies should focus on improving model generalizability across diverse clinical settings, expanding predictor availability, and exploring dynamic, time-series modeling to enable continuous and adaptive risk assessment in ICU practice.

In conclusion, this study developed a CoxBoost ML model for predicting 28-day mortality in ICU-admitted CAP patients with AKI, demonstrating superior predictive performance compared to traditional scoring systems. The integration of SHAP analysis enhanced model interpretability, providing insights into key predictors of mortality. Additionally, the development of a web-based application offered a practical tool for real-time risk estimation, supporting early clinical decision-making in ICU settings.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the publicly available MIMIC-IV database, which contains de-identified health records of critically ill patients. Access to the MIMIC-IV database requires completion of the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) course and adherence to the database’s data use agreement. Researchers can request access and download the dataset from the PhysioNet repository [](.) ([https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv)).

References

Chen, D. et al. Impact of acute kidney injury on in-hospital outcomes in Chinese patients with community acquired pneumonia. BMC Pulm Med. 21, 143 (2021).

Almutairi, A. et al. The prevalence of acute kidney injury in patients with community-acquired pneumonia who required mechanical ventilation. Ann. Saudi Med. 44, 104–110 (2024).

Murugan, R. et al. Acute kidney injury in non-severe pneumonia is associated with an increased immune response and lower survival. Kidney Int. 77, 527 (2009).

Li, M. et al. Development and deployment of interpretable machine-learning model for predicting in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with acute kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 44, 1886–1896 (2022).

Gao, T. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Ren. Fail. 46, 2316267 (2024).

Ferreira, F. L., Bota, D. P., Bross, A., Mélot, C. & Vincent, J. L. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA 286, 1754–1758 (2001).

EL-Manzalawy, Y. et al. OASIS +: leveraging machine learning to improve the prognostic accuracy of OASIS severity score for predicting in-hospital mortality. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 21, 156 (2021).

Zaka, A. et al. Machine learning for prediction of all-cause mortality in acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 45, ehae6663448 (2024).

Zaka, A. et al. Machine-learning versus traditional methods for prediction of all-cause mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open. Heart. 12, e002779 (2025).

Wu, H. et al. Comparison between traditional logistic regression and machine learning for predicting mortality in adult sepsis patients. Front. Med. 11, 1496869 (2025).

Kellum, J. A. & Lameire, N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit. Care. 17, 204 (2013).

Fan, S. & Ma, J. The value of five scoring systems in predicting the prognosis of patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory failure. Sci. Rep. 14, 4760 (2024).

Bahlis, L. F., Diogo, L. P. & Fuchs, S. C. Charlson comorbidity index and other predictors of in-hospital mortality among adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J. Bras. Pneumol. 47, e20200257 (2021).

Kahraman, F., Yılmaz, A. S., Ersoy, İ., Demir, M. & Orhan, H. Predictive outcomes of APACHE II and expanded SAPS II mortality scoring systems in coronary care unit. Int. J. Cardiol. 371, 427–431 (2023).

Guo, W. et al. The impact of Contrast-Associated acute kidney injury on All-Cause mortality in older patients after coronary angiography:a 7.5-year Follow-Up. Angiology 75, 434–440 (2024).

He, H. et al. A comparison between two definitions of Contrast-Associated acute kidney injury for Long-Term mortality in elderly and Non-elderly patients after elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 720857 (2021).

Chen, D., Tan, Y. & Wan, X. Impact of angiotensin receptor blockers use on In-Hospital mortality in Community-Acquired pneumonia patients with hypertension. Kidney Dis. 9, 424–432 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. The effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: an observational study using the MIMIC database. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 918385 (2022).

Sheng, S. et al. Association between hemoglobin and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: evidence from two large databases. BMC Infect. Dis. 24, 1450 (2024).

Lee, G. et al. Association of hemoglobin concentration and its change with cardiovascular and All-Cause mortality. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 7, e007723 (2018).

Su, L. et al. Association of ibuprofen prescription with acute kidney injury among hospitalized children in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e210775 (2021).

Ungprasert, P., Cheungpasitporn, W., Crowson, C. S. & Matteson, E. L. Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26, 285–291 (2015).

Hatton, G. E. et al. Do early non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia worsen acute kidney injury in critically ill trauma patients? An inverse probability of treatment weighted analysis. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 89, 673 (2020).

Arons, M. M. et al. Effects of ibuprofen on the physiology and survival of hypothermic sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 27, 699 (1999).

Wang, H. et al. NSAID treatment before and on the early onset of acute kidney injury had an opposite effect on the outcome of patients with AKI. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 843210 (2022).

Abendaño-Rivera, D. F. et al. BUN/creatinine ratio associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis and acute kidney injury. Ann. Hepatol. 29, 101439 (2024).

Pando, E. et al. Early Changes in Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) Can Predict Mortality in Acute Pancreatitis: Comparative Study between BISAP Score, APACHE-II, and Other Laboratory Markers—A Prospective Observational Study. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6643595 (2021). (2021).

Rachoin, J. S. et al. The fallacy of the bun:creatinine ratio in critically ill patients. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 27, 2248–2254 (2012).

Ma, S. et al. Sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: A disease of the microcirculation. Microcirculation 26, e12483 (2019).

Chen, Y. Y. et al. Norepinephrine administration is associated with higher mortality in Dialysis requiring acute kidney injury patients with septic shock. J. Clin. Med. 7, 274 (2018).

Ramesh, A. et al. Use of vasopressors in patients with acute kidney injury on continuous kidney replacement therapy. PLOS ONE. 19, e0315643 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Vasoactive-Inotropic score as a promising predictor of acute kidney injury in adult patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 70, 586 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Prognostic evaluation of the norepinephrine equivalent score and the vasoactive-inotropic score in patients with sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1415769 (2024).

Kolhe, N. V. et al. Impact of compliance with a care bundle on acute kidney injury outcomes: A prospective observational study. PLOS ONE. 10, e0132279 (2015).

See, C. Y. et al. Improvement of composite kidney outcomes by AKI care bundles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 27, 390 (2023).

Ponce, D., Zorzenon, C., de Santos, P. F. & Balbi, A. L. N. Y. dos Early nephrology consultation can have an impact on outcome of acute kidney injury patients.

Rhee, H., Park, M. & Kim, I. Y. Nephrology consultation improves the clinical outcomes of patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 44, 102–110 (2025).

Investigators, T. S. A. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2000741 (2020).

Malbrain, M. L. N. G. et al. Urine output is an early and strong predictor of acute kidney injury and associated mortality: A systematic literature review of 50 clinical studies. Ann. Intensive Care. 14, 110 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Early palliative care consultation in the medical ICU: A cluster randomized crossover trial. Crit. Care Med. 47, 1707–1715 (2019).

Helgeson, S. A. et al. Early versus usual palliative care consultation in the intensive care unit. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 40, 544–551 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the MIT Laboratory for Computational Physiology for providing access to the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. We sincerely appreciate the efforts of the MIMIC-IV development team in maintaining and curating this valuable critical care dataset, which has significantly contributed to advancements in clinical research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. T.L., M.L., N.W., and T.Li collected, cleaned, and reviewed the literature and data. G.W. revised and proofread the manuscript. T.H. and Z.S. critically reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, W., Wang, G., Liu, T. et al. A machine learning model for predicting 28-day mortality in ICU patients with community-acquired pneumonia and acute kidney injury. Sci Rep 15, 43454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27236-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27236-x