Abstract

Phoradendron nervosum (hemiparasitic plant) exhibits remarkable metabolic plasticity, with significant variations in bioactive compound content, metabolite profiles, and antioxidant capacity depending on the host species (Laurus nobilis L., Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L., Populus alba L.) and organ type (leaves vs. fruits). A multi-method approach combining spectrophotometry, complementary antioxidant assays (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP), and complete metabolomic profiling by LC–MS was used to elucidate the biochemical interactions between P. nervosum and its hosts. The results obtained showed a differential distribution of total phenolic and flavonoid compounds, with leaves characterized by higher flavonoid concentrations (e.g., up to 0.286 mg QE/g DW). At the same time, fruits exhibited host-mediated modulations, especially in the species L. nobilis (e.g., the highest TPC at 2.723 mg GAE/g DW). Antioxidant activity was consistently higher in leaves (e.g., up to 41.26 µmol Trolox/g DW in DPPH assay), correlating with their enriched presence of phenolic acids and glycosylated flavonoids. The host species played a determining role in antioxidant capacity, as H. rosa-sinensis-associated plants exhibited the highest levels (e.g., 14.53 µmol Trolox/g DW in ABTS, 24.06 µmol Fe2+/g DW in FRAP). Correlation analysis suggested complex biochemical trade-offs influencing metabolic allocations. A diversity of bioactive compounds was identified by LC–MS, highlighting the synergistic interaction between metabolites in defining the physiological response of P. nervosum. Our results highlight its adaptive versatility and ecological significance, but also potential pharmacological applications, given that related mistletoe species from Europe are already used in antitumor treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parasitic plants, widely referred to as mistletoe, form enduring associations with numerous host plants. They are found worldwide in humid tropical, arid, and temperate areas; nonetheless, their occurrence is limited in regions with low temperatures1. Mistletoes are classified as hemiparasites because they can photosynthesize organic compounds. Nevertheless, their uptake of water and nutrients relies on the host plant’s xylem2. Hemiparasitic plants can perform photosynthesis owing to their production of chlorophyll, yet they rely on a host plant for vital resources like water and mineral nutrients3. To effectively penetrate the host, these plants form a specialized root (haustorium) that engages with the host’s vascular systems (phloem or xylem), potentially affecting the host’s physiology and chemical makeup4. American mistletoe includes the whole Phoradendron genus, known for hemiparasitism and its capacity to impact various shrubs and trees5. Plants belonging to the Phoradendron genus can perform photosynthesis, indicating they have chloroplasts. Nonetheless, they continue to rely on their host plant’s vascular system for water and nutrients. Consequently, this interaction can activate physiological responses, impacting both organisms, especially in the production and buildup of secondary metabolites6. Phoradendron nervosum Oliv. (mistletoe, graft, or matapalo) is a commonly found hemiparasitic shrub present in temperate, arid, and tropical areas of the Americas, spanning from Mexico to Bolivia1. Its key trait is its capability to infect the stems or branches of different host plants5. This species ranks among the most prevalent mistletoe types, with about 1600 species found globally, categorized into 88 genera within the Loranthaceae family (comprising 1000 species) and the Viscaceae family (consisting of 550 species)7.

Mistletoe varieties are divided into two groups: European and American. Phoradendron is the most prevalent among American mistletoes. Unfortunately, because of insufficient research, the particular mistletoe genera found in Ecuador are not clearly understood.

However, P. nervosum has been documented in various areas of the capital, making it a subject of interest for study due to its prominent occurrence in diverse host plants5.

The parasitism of P. nervosum triggers various types (biotic and abiotic) of responses in its host plants. Pérez et al.8 indicate that biotic stress from parasitic plants adversely affects host plant growth and reproduction, whereas abiotic stress linked to weather elements like droughts or storms worsens these changes. While research has explored the morphological and physiological impacts on host plants, there has been less focus on more nuanced changes, like differences in secondary metabolites.

Secondary metabolites are substances generated by plants as a reaction to various forms of stress, aiding in their survival. Among these, phenolic compounds are notably important because of their advantageous effects on human health, especially their antioxidant capabilities, which are vital in fighting oxidative stress9. Multiple research efforts have shown that Phoradendron species possess significant levels of phenolic compounds and flavonoids, crucial for their antioxidant capabilities and medicinal potential9.

The research into phenolic metabolites has been propelled by the therapeutic potential of these compounds. Approximately 60% of the world’s population depends on medicinal plants for healthcare. Nonetheless, the absence of regulations regarding chemical makeup raises concerns about the equilibrium between toxicity and effectiveness. Consequently, research on the isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds found in P. nervosum is essential to enhance its use in drug development10,11.

Studies on secondary metabolites in parasitic plants remain scarce in Ecuador. Therefore, research on the fruits of P. nervosum is essential to explore its phytochemical and pharmacological potential12.

This study represents an innovative approach in the research on P. nervosum, as it identifies the influence of host plants on its antioxidant activity, determined by the variation in the concentrations of phenolic compounds and flavonoids. In Europe, related mistletoe species are used in antitumor treatments, highlighting the importance of further exploring the pharmacological potential of this plant for future medical applications.

Results

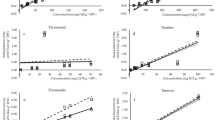

The total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) varied among the samples of P. nervosum collected from different host trees (Laurus nobilis—Laurel, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis—Cucarda, Populus alba—Alamo). In general, leaves accumulated higher levels of these compounds compared to fruits.

The TPC in leaves ranged from 2.590 to 2.708 mg GAE/g DW in samples from Laurel and from 2.592 to 2.705 mg GAE/g DW in those from Cucarda, with average values of 2.645 ± 0.041 mg GAE/g DW and 2.646 ± 0.042 mg GAE/g DW, respectively. In fruits, TPC values ranged from 2.580 to 2.723 mg GAE/g DW (Laurel) and from 2.613 to 2.712 mg GAE/g DW (Cucarda), yielding average values of 2.653 ± 0.048 mg GAE/g DW and 2.646 ± 0.042 mg GAE/g DW, respectively.

For TFC, leaf samples from Laurel ranged from 0.269 to 0.285 mg QE/g DW, and from 0.271 to 0.286 mg QE/g DW in Cucarda, with respective averages of 0.275 ± 0.005 mg QE/g DW and 0.280 ± 0.005 mg QE/g DW. In fruits, TFC values ranged from 0.249 to 0.266 mg QE/g DW in Laurel and from 0.244 to 0.257 mg QE/g DW in Cucarda, with corresponding averages of 0.260 ± 0.006 mg QE/g DW and 0.249 ± 0.006 mg QE/g DW (Fig. 1).

These results indicate that leaves of P. nervosum consistently accumulate higher concentrations of phenolic and flavonoid compounds than fruits, regardless of the host species. The highest TPC was observed in fruits parasitizing Laurel (2.723 mg GAE/g DW), while the highest TFC was recorded in leaves from Cucarda (0.286 mg QE/g DW). These differences may be explained by host-dependent metabolic modulation, organ-specific biosynthetic activity, and environmental factors. The elevated phenolic and flavonoid content in leaves may reflect their role in oxidative stress response and parasitic adaptation mechanisms (Fig. 1).

The antioxidant capacity of P. nervosum leaves and fruits parasitizing different host trees (Laurel—L. nobilis, Cucarda—H. rosa-sinensis, Alamo—P. alba) was evaluated using ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assays. The results showed distinct patterns of antioxidant activity associated with both the plant organ and the host species.

In the ABTS assay, leaves exhibited the highest antioxidant activity, particularly those parasitizing Cucarda (14.53 ± 0.28 µmol Trolox/g DW), followed by Álamo (12.55 ± 0.14 µmol Trolox/g DW) and Laurel (12.45 ± 0.07 µmol Trolox/g DW). In contrast, fruits showed markedly lower activity: 3.25 ± 0.11 µmol Trolox/g DW (Laurel), 2.90 ± 0.02 µmol Trolox/g DW (Álamo), and 2.88 ± 0.02 µmol Trolox/g DW (Cucarda).

The DPPH assay mirrored these findings. Leaves from Cucarda recorded the highest antioxidant capacity (41.26 ± 0.48 µmol Trolox/g DW), followed by those from Álamo (37.10 ± 1.06 µmol Trolox/g DW) and Laurel (36.94 ± 1.24 µmol Trolox/g DW). In fruits, antioxidant values were lower overall, though Laurel fruits showed relatively higher activity (26.14 ± 0.34 µmol Trolox/g DW) compared to Cucarda (11.63 ± 0.43 µmol Trolox/g DW) and Álamo (7.90 ± 0.26 µmol Trolox/g DW).

In the FRAP assay, which measures ferric reducing antioxidant power, leaves again displayed superior activity. The highest value was found in Cucarda (24.06 ± 0.33 µmol Fe2+/g DW), followed by Álamo (22.22 ± 0.05 µmol Fe2+/g DW) and Laurel (20.77 ± 0.20 µmol Fe2+/g DW). Among the fruits, the highest FRAP value was observed in those parasitizing Laurel (4.33 ± 0.16 µmol Fe2+/g DW), while Álamo (2.94 ± 0.17 µmol Fe2+/g DW) and Cucarda (2.67 ± 0.06 µmol Fe2+/g DW) recorded the lowest values.

These findings confirm that P. nervosum leaves possess greater antioxidant potential than fruits, regardless of the host. Furthermore, the host species significantly influences antioxidant activity, suggesting that interactions between the parasitic plant and its host modulate metabolic pathways related to oxidative stress defense (Fig. 2).

Heatmap illustrating antioxidant activity in fruits and leaves of P. nervosum parasitizing three host species (Laurel—L. nobilis, Cucarda—H. rosa-sinensis, Alamo—P. alba), as determined by ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP assays. The color gradient represents antioxidant capacity (μmol Trolox Fe2+ equivalent per gram of dry weight), with notable differences observed across host species and plant parts.

The correlation analysis between antioxidant activity (ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP) and bioactive compound content (TPC and TFC) in P. nervosum (leaves and fruits) revealed host- and tissue-dependent associations. These correlations help elucidate the functional relationship between secondary metabolites and antioxidant mechanisms in this hemiparasitic species.

A moderate negative correlation was observed between FRAP and DPPH (r = − 0.290, p < 0.01), and between FRAP and TPC (r = − 0.352), particularly in samples from Cucarda Leaf (r = − 0.51) and Alamo Leaf (r = − 0.50). Interestingly, FRAP was strongly and positively correlated with TFC in Fruit Alamo (r = 0.933), suggesting that in this specific host-tissue combination, flavonoids significantly contribute to ferric reducing power.

DPPH and ABTS showed a strong negative correlation (r = − 0.463, p < 0.001), particularly in Laurel Fruit and Alamo Leaf (both r = − 0.684), indicating potential divergence in radical scavenging mechanisms depending on host-derived metabolites. This inverse relationship may be influenced by differences in compound solubility or the types of phenolics present.

In contrast, ABTS and DPPH displayed a moderate positive correlation with TPC (r = 0.256* for DPPH), especially in fruit samples from Cucarda and Cucarda Leaf (r = 0.557), suggesting a stronger role of total phenolics in radical neutralization under these conditions.

The correlation between TPC and TFC was also negative overall (r = − 0.327**, p < 0.01), particularly in Cucarda Fruit and Laurel Leaf, indicating that the accumulation of one class of compounds may occur at the expense of the other, depending on tissue type or host interaction.

These findings underscore the complex and host-modulated biochemical landscape in P. nervosum. The leaf samples tended to show more negative correlations across antioxidant assays and phenolic metrics (e.g., Cucarda Leaf: FRAP vs. DPPH, r = − 0.47), while fruits, particularly those from Alamo, displayed stronger positive correlations (e.g., FRAP vs. TFC, r = 0.933). This may reflect differential biosynthetic prioritization depending on tissue function and the metabolic influence of the host.

Overall, the results suggest that both the host species and plant organ significantly influence the antioxidant mechanisms in P. nervosum, with potential implications for its phytochemical potential and ecological adaptation (Fig. 3).

Correlation matrix between antioxidant capacity assays (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP) and bioactive compounds (TPC and TFC) in leaves and fruits of P. nervosum parasitizing three different host species (Laurel—L. nobilis, Cucarda—H. rosa-sinensis, Alamo—P. alba). Correlation coefficients (r) are presented in each cell, with statistical significance indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Diagonal plots represent the density distributions of each variable, while lower triangular panels show scatterplots with fitted regression curves. The matrix illustrates host- and tissue-specific relationships between phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties.

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC–MS) was used to identify the metabolic profile and bioactive compounds present in the leaves and fruits of P. nervosum, a hemiparasitic plant of ecological and pharmacological interest. The analysis, performed in positive and negative ionization modes, revealed a wide spectrum of secondary metabolites, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, glycosides, and other specialized compounds, which varied according to the host plant and plant tissue (see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 for representative chromatograms; Table 1).

Among the most prominent compounds detected in positive ionization mode were chlorogenic acid, hyperoside, vitexin, isovitexin, quercetin 3-β-D-galactopyranoside, rutin, kaempferol-3-O-glucuronoside, and mangiferin, recognized for their antioxidant and therapeutic potential. Additionally, specialized metabolites such as resveratrol, stigmasterol, liquiritin, and diosmetin were identified, contributing to the pharmacological richness of the species.

In the negative ionization mode, key phenolic acids such as trans-caffeic acid and sinapinic acid, as well as sugars like sorbitol and isobaric monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, mannose, galactose), were detected. Several compounds exhibited tissue-specific occurrence. For example, rutin, hyperoside, and chlorogenic acid were predominantly associated with the leaves, while flavonoid glycosides such as mirificin and diosmin were more abundant in fruits.

These findings reflect a complex and diverse phytochemical composition in P. nervosum, modulated by both tissue type (leaf vs. fruit) and host plant (Laurel—L. nobilis, Cucarda—H. rosa-sinensis, Alamo—P. alba). This chemical diversity underscores the adaptive capacity and potential bioactivity of this parasitic species (see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 for representative chromatograms).

Discussion

The present research unequivocally establishes the notable metabolic plasticity of the hemiparasitic plant P. nervosum. Significant variations observed in the content of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, detailed metabolite profile, and antioxidant capacity, both between organs and as a function of the host species (Laurel—L. nobilis, Cucarda—H. rosa-sinensis, Alamo—P. alba), underscore the adaptive capacity of this species. Using a multi-method approach that combined spectrophotometry, complementary antioxidant assays (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP), and exhaustive metabolomic profiling by LC–MS, this study offers a detailed perspective on the complex biochemical dance that defines the interaction between P. nervosum and its diverse hosts, revealing far-reaching functional and ecological implications.

A central finding is the differential distribution of total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) between leaves and fruits. Leaves of P. nervosum13,14 generally tended to accumulate consistently higher levels of TFC. This greater investment in flavonoids in leaf tissue, especially marked in plants parasitizing the Cucarda host (reaching 0.286 mg QE/g DW), is consistent with the known protective role of these compounds against oxidative damage and as herbivore deterrents. In contrast, the pattern for TPC was more complex, indicating a more nuanced regulation than a simple leaf-fruit dichotomy.

The host’s influence on the phenolic profile was particularly evident in the case of TPC, where P. nervosum fruits on Laurel exhibited the highest levels (up to 2.723 mg GAE/g DW), even surpassing leaves in some instances. This phenomenon suggests potent modulation by the host, which could involve the direct translocation of phenolic compounds or their precursors from Laurel, a species known for its rich phytochemistry15, to the parasite’s fruits16,17. LC–MS analysis supports this view by identifying a diversity of phenolic acids (e.g., chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid) and glycosylated flavonoids (e.g., rutin, hyperoside). The predominance of rutin and hyperoside in leaves underscores their foliar defensive role18, while differential accumulation in fruits, such as mirificin and diosmin, points to organ-specific strategies possibly linked to seed defense or interaction with dispersers, orchestrated by the host interaction19,20.

Antioxidant capacity, evaluated by three complementary methods, revealed a more consistent pattern of superiority in leaves compared to fruits. This elevated leaf antioxidant activity is physiologically expected, given the high production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inherent in the photosynthetic process and continuous exposure to environmental stressors21,22. The antioxidant machinery in leaves must be robust to maintain redox homeostasis and protect vital cellular structures. LC–MS data provide the molecular basis for this observation, with the detection of compounds such as resveratrol, chlorogenic acid, rutin, hyperoside, and quercetin 3-β-D-galactopyranoside, all recognized for their potent antioxidant properties and frequent localization in photosynthetically active tissues23,24.

The host species emerged as a determining factor of antioxidant capacity, as P. nervosum leaves parasitizing Cucarda (H. rosa-sinensis L.) consistently exhibited the highest antioxidant activity in all assays (e.g., 41.26 µmol Trolox/g DW in DPPH), which positively correlated with their high TFC levels. This suggests that interaction with Cucarda could induce a phytochemical profile particularly effective in neutralizing free radicals. This induction could be the result of the transfer of specific metabolites from Cucarda that act as direct antioxidants or as elicitors of defense pathways in the parasite, or a response of the parasite to a particular oxidative stress environment imposed by this host.

Correlation analysis between bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity unveiled a more complex network of interactions than expected. The absence of a universal positive correlation between TPC/TFC and antioxidant activity, along with the appearance of significant negative correlations (e.g., FRAP vs. DPPH; FRAP vs. TPC), highlights the diversity of the compounds involved and the inherent mechanistic differences of the antioxidant assays used25,26. While the strong positive correlation between FRAP and TFC in fruits of P. nervosum parasitizing Alamo (r = 0.933) points to flavonoids as the main reducing agents in that specific context, negative correlations suggest that different subsets of metabolites, with varying reactivities and solubilities, contribute differentially to the results of each assay. The general negative correlation observed between TPC and TFC (r = − 0.327) could also be indicative of biosynthetic "trade-offs," where the plant preferentially allocates resources to the synthesis of one class of phenols over another, depending on environmental signals and physiological demands27.

Metabolomic profiling by UHPLC-Ion Trap MS was crucial for transcending the limitations of spectrophotometric measurements of “total phenols” or "total flavonoids." The tentative identification of a wide range of metabolites, including not only diverse phenolic acids and glycosylated flavonoids (such as rutin, hyperoside, vitexin, mangiferin), but also other compounds like sterols (stigmasterol, campesterol) and triterpenes (obacunone, uncaric acid), offers a much richer picture of P. nervosum's chemical composition. This diversity underscores that the observed biological activity is likely the result of the synergistic, additive, or even antagonistic action of multiple compounds, and not just of the major classes. Detailed profiling allows for the formulation of hypotheses about the specific roles of these compounds and how their biosynthesis is orchestrated in response to the host.

The demonstrated metabolic plasticity of P. nervosum has profound ecological implications. The ability to modulate its phytochemistry in response to different hosts is undoubtedly a fundamental adaptive strategy that allows the parasite to exploit a wider range of resources and persist in heterogeneous environments. Optimized chemical defense and enhanced antioxidant capacity, depending on the host, can confer significant advantages in terms of resilience to abiotic stress, defense against host-specific herbivores and pathogens, and even in interspecific competition28. This chemical variability could, furthermore, play a role in determining host specificity or preference, as well as in structuring the communities of organisms associated with the parasite29

From an application point of view, the identification of compounds with recognized pharmacological activity underlines the potential of the analyzed species as a reservoir of valuable phytochemicals, which determine a notable antioxidant activity. Thus, the leaves of P. nervosum plants parasitizing on H. rosa-sinensis (Cucarda), suggest the potential of the species in the nutraceutical/coadjuvant therapeutic products industry. However, the biotechnological exploitation of parasitic plants presents unique challenges. The marked host-dependent chemical variability, as demonstrated in this study, implies that the standardization of extracts to ensure consistent composition and efficacy would be complex and would require rigorous control of the host source30. Furthermore, exhaustive toxicological and bioavailability studies are needed before considering any direct application.

In conclusion, this study illuminates the intricate relationship between P. nervosum, its specific organ, and the host species, manifested through a pronounced plasticity in its secondary metabolite profile and antioxidant capacity. The combination of biochemical assays with LC–MS metabolomic profiling has provided a more complete view.

To deepen our understanding, future research will prioritize: (a) structural confirmation and absolute quantification of key metabolites using reference standards and NMR techniques; (b) conducting comparative metabolomic and transcriptomic ("multi-omics") studies to correlate gene expression profiles with metabolite profiles in response to different hosts, thereby identifying regulated biosynthetic pathways; (c) evaluating the bioactivity of purified fractions or compounds in more specific assays (e.g., anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cytotoxic); and (d) investigating the origin and significance of less common, tentatively identified compounds. These approaches will not only further unravel the chemical ecology of host-parasite interactions but could also pave the way for the discovery of new bioactive molecules and sustainable strategies for their production.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study illuminates the intricate relationship between P. nervosum, its specific organ, and the host species, manifested through a pronounced plasticity in its secondary metabolite profile and antioxidant capacity. The combination of biochemical assays with LC–MS metabolomic profiling has provided a more complete view of the biochemical interactions in this hemiparasitic plant. Our findings highlight the adaptive versatility of P. nervosum, demonstrating how host-dependent variations influence phenolic and flavonoid contents, as well as antioxidant activity, with leaves generally showing higher levels than fruits. Ecologically, this plasticity enables the parasite to thrive in diverse environments by optimizing defense mechanisms against stress and herbivores. Pharmacologically, the identification of bioactive compounds with antioxidant potential underscores the species’ promise for applications similar to European mistletoes in antitumor treatments, potentially advancing drug development in Ecuador where such research is scarce. This work contributes a novel multi-method approach to understanding parasitic plant metabolism, filling a gap in local phytochemical studies and paving the way for future explorations in ecological and therapeutic contexts.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Fully developed leaves and ripe fruits of P. nervosum were collected in March 2023 from different host tree species (Laurus nobilis L.—Laurel, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L.—Cucarda, Populus alba L.—Alamo) in Pichincha, a region encompassing diverse climatic and ecological conditions. The species and hosts were accurately identified by a trained taxonomist with experience in parasitic flora of the Andean region, and voucher specimens have been documented digitally under the identifier ECU-HVIR-2025-015.

The species was identified by a trained taxonomist with experience in parasitic flora of the Andean region. Sampling was conducted at an elevation of approximately 2500 m above sea level, where mean temperatures range between 17 and 29 °C. The selection of this site was intended to capture potential host-mediated and environmental influences on the antioxidant potential, phenolic content, and metabolomic profile of P. nervosum tissues (leaves and fruits).

Extraction of bioactive constituents

The extraction of bioactive constituents from P. nervosum leaves and fruits was conducted based on a previously reported method (Claros, 2021)31, with protocol modifications to enhance suitability for this species and tissue types. Fresh, mature plant material (both fruits and leaves) was manually ground using a sterilized mortar and pestle until a uniform consistency was achieved. To ensure results were expressed on a dry weight (DW) basis and account for water content variability, subsamples of fresh material were oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight, and the fresh-to-dry weight ratio was applied to normalize all quantitative data. An aliquot of 1.0 g of the resulting material was accurately weighed and placed into 15 mL Falcon tubes containing 10 mL of 96% ethanol. The suspensions were gently stirred using a glass rod and subsequently incubated at 5 °C for 72 h to maximize the extraction of antioxidant and phenolic compounds. Following incubation, the extracts were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain clear supernatants. To measure the supernatant’s absorbance, a UV–Vis spectrophotometer was used.

Determination of total phenolic content

The Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric assay32 with adaptations for this species was used to quantify the total phenolic content from P. nervosum extracts. The method consists of mixing 0.4 mL of ethanolic extract, 2.0 mL of 10% (v/v) diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and 1.6 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution. This mix was kept for 30 min at ambient temperature, in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer calibration curve was generated using standards, and results (expressed in milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry weight, mg GAE/g DW) were obtained using a calibration curve generated using gallic acid (0–250 mg/L) as a standard. Blank samples prepared by substituting the extract with ethanol were used.

Determination of total flavonoid content

To enhance the understanding of the antioxidant profile, the flavonoid content was evaluated via the aluminum chloride colorimetric technique as outlined by Pekal et al.33, including minor adjustments. In this assay, 1.0 mL of ethanolic extract was combined with 1.5 mL of absolute ethanol, 100 µL of 1 M sodium acetate (CH3COONa), 100 µL of 10% (v/v) aluminum chloride (AlCl3), and 2.3 mL of distilled water. The solutions were held at room temperature for 40 min, and then absorbance measurements were recorded at 435 nm. Quercetin served as a reference standard for creating a calibration curve (0–1.5 mg/L), with results reported as milligrams of quercetin equivalents per gram of dry weight (mg QE/g DW).

Antioxidant activity assays

The antioxidant potential of P. nervosum extracts (obtained from leaves and fruits) was evaluated using three different and complementary in vitro tests: ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging, and 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical cation decolorization. These assays offered a thorough assessment of the extracts’ ability to donate electrons and neutralize radicals.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The FRAP assay, centered on the conversion of ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) ions, was conducted according to the procedure outlined by Rajurkar et al.34, with alterations. The FRAP solution was made by combining 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 40 mM HCl, and 20 mM FeCl3·6H2O. For every sample, 100 µL of extract was combined with 300 µL of distilled water and 3.0 mL of the recently prepared FRAP reagent. Following a 30 min incubation at ambient temperature, absorbance was recorded at 593 nm. A standard curve was created with FeSO4 7H2O (0–5 mM), and antioxidant capacity was represented as ferrous ion equivalents (Fe2+).

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay

The DPPH assay, which evaluates the capacity of antioxidants to scavenge free radicals, was adapted from the procedures of Sachett et al.35 and Thaweesang36, with slight adjustments. A DPPH solution of 1 µg/L⁻1 concentration was previously prepared and mixed with 0.1 mL of extract in a final volume of 2.1 mL, the mix being kept for 30 min, in the dark, at ambient temperature. Absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. Trolox was used as the standard required to make the calibration curve. The results were expressed as Trolox equivalents.

2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay

For the ABTS assay, the method reported by Kuskoski et al.37 was followed. The ABTS•+ radical cation was generated and diluted to an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.10 at 754 nm. Subsequently, 20 µL of the extract was mixed with 2.0 mL of the ABTS solution and allowed to incubate in the dark for 7 min. Absorbance was recorded at 754 nm, and outcomes were expressed in Trolox equivalents (TE) as well.

LC–MS analysis

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC–MS) was used for the preliminary identification of bioactive metabolites from parallel samples of the previously analyzed P. nervosum batches. For this, ethanolic extracts were made by macerating 1.0 g of lyophilized tissue in 20 mL of 80% ethanol to optimize for metabolomic detection and prevent instrument issues, while maintaining consistency with spectrophotometric samples. The extracts were stored at 30 °C for 2 h with continuous shaking39. Following extraction, the suspensions were centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 rpm at 4 °C, and the supernatants were filtered (0.22 µm). The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation at 30 °C, and the concentrated extracts were stored at − 20 °C in sealed polypropylene containers until chromatographic analysis.

For the analyses, a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to an Ion Trap mass spectrometer was used, the Accucore Vanquish C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm) maintained at 35 °C, with a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, 10 µL injection volume, mobile phase was represented by formic acid (0.1%) in water40. Mass spectral data acquisition was conducted in both positive and negative ionization modes, and compounds were tentatively identified by comparing retention times and mass fragmentation patterns with reference standards and spectral libraries, including PubChem, ChEBI, METLIN, and LC–MS compound databases41.

Metabolite annotation and data processing were performed using MZmine 2 (version 2.53; available at https://github.com/mzmine/mzmine242), with additional confirmation based on values from previously published literature and comparison with databases. This approach enabled the comprehensive characterization of host-dependent variations in the phytochemical profile of P. nervosum tissues41.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (R version 4.4.1). To evaluate the impact of host species and tissue type (leaf versus fruit) on antioxidant activity, total phenolic compounds, and flavonoid levels, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used; statistical significance was determined at a level of p < 0.05. Experimental results were reported as means ± standard deviation (SD), based on triplicate independent assays. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine potential associations between levels of specific secondary metabolites and antioxidant capacity (as determined by FRAP, DPPH, and ABTS assays). These correlations provided further insights into the biochemical relationships underpinning the antioxidant functionality of P. nervosum across different host associations.

Data availability

All relevant data supporting the findings of our study have been included in the manuscript. Additional information is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Dr. Raluca Mihai. The voucher specimen of the studied parasitic plant has been documented digitally and catalogued under the identifier ECU-HVIR-2025-015, pending inclusion in the digital repository.

References

Muche, M., Muasya, A. M. & Tsegay, B. A. Biology and resource acquisition of mistletoes, and the defense responses of host plants. Ecol. Process. 11(1), 24 (2022).

Teixeira-Costa, L. & Davis, C. C. Life history, diversity, and distribution in parasitic flowering plants. Plant Physiol. 187(1), 32–51 (2021).

Scheidel, A. Evaluating the multi-level community effects of root hemiparasites in Northern Illinois. MS Thesis, Illinois State University (2021).

González, F. & Pabón-Mora, N. The remarkable diversity of parasitic flowering plants in Colombia. Bot. Rev. 89, 331–385 (2023).

Carrera, M., Altamirano, L. & Barragán, K. Host species of the hemiparasitic shrub Phoradendron nervosum Oliv. in densely urban areas of Quito, Ecuador. ACI Avances Cienc. Ing. 15(2), 9 (2023).

Khristi, V. & Patel, V. H. Therapeutic potential of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis: A review. Int. J. Nutr. Diet. 4, 105–123 (2017).

Mudgal, G. et al. Mitigating the mistletoe menace: Biotechnological and smart management approaches. Biology 11(11), 1645 (2022).

Pérez-de-Luque, A., Moreno, M. & Rubiales, D. Host plant resistance against broomrapes (Orobanche spp.): Defence reactions and mechanisms of resistance. Ann. Appl. Biol. 152, 131–141 (2008).

Twyford, A. D. Parasitic plants. Curr. Biol. 28(13), R857–R859 (2018).

Assanga, S. B. I. et al. Comparative analysis of phenolic content and antioxidant power between parasitic Phoradendron californicum (toji) and their hosts from Sonoran Desert. Results Chem. 2, 100079 (2020).

Paniagua-Zambrana, N. Y., & Bussmann, R. W. Phoradendron nervosum Oliv. Santalaceae. In N. Paniagua-Zambrana & R. Bussmann (Eds.), Ethnobotany of the Andes. Ethnobotany of Mountain Regions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77093-2_229-1, (2020).

Mendoza, M. Inducción de metabolitos de interés nutracéutico en germinados de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) y el efecto de su consumo en un modelo de dislipidemia. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico, (2018).

Brunetti, C., Di Ferdinando, M., Fini, A., Pollastri, S., & Tattini, M. Flavonoids as antioxidants and developmental regulators: Relative significance in plants and humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(5), 1377 (2018).

Fang, C., Zhang, R., Wei, Y., Ma, K., Wu, S., & Pei, Z. Plant adaptation to environmental stress: An epigenetic perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 25(10), 1020–1035, (2020).

Ezzat, S. M., Salama, M. M., Mahrous, E. A., El-Fishawy, A. M., & El-Khatib, A. H. Phytochemical profiling and biological assessment of Laurus nobilis L. leaves and fruits. Foods. 9(7), 912, (2020).

Jiang, F., Zhang, L., & Zhou, J. Molecular dialogue between parasitic plants and their hosts. New Phytol. 230(1), 66–72 (2021).

Schneider, A. C., Wüst, M., Harrison, J. G., & van Dam, N. M. Uptake and modification of host-plant iridoid glycosides by the parasitic plant Cuscuta gronovii. New Phytol. 230(3), 1207–1220 (2021).

Ganeshpurkar, A., & Saluja, A. K. The pharmacological potential of rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 25(2), 149–164 (2017).

Cipollini, D., Walters, D., & Van Dam, N. M. The ‘moving target’ model of plant defense: The roles of evolution, development, and plasticity. J. Chem. Ecol. 43(10), 927–941 (2017).

Pan, S., Li, X., Xiong, L., Cao, J., Tan, Z., Tu, Z., Lu, J., & Chen, X. Host tree species significantly influence the phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activities of Viscum coloratum. Molecules, 27(15), 4907 (2022).

Das, K., & Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci., 2, 53 (2014).

Noctor, G., Reichheld, J. P., & Foyer, C. H. ROS-related redox regulation and signaling in plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 80, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.013, (2018).

Li, Y., Kong, D., Fu, Y., Sussman, M. R., & Wu, H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 148, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.01.006, (2020).

Yao, L. H., Jiang, Y. M., Shi, J., Tomás-Barberán, F. A., Datta, N., Singanusong, R., & Chen, S. S. Flavonoids in food and their health benefits. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 76(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-021-00890-2, (2021).

Apak, R., Özyürek, M., Güçlü, K., & Çapanoğlu, E. Antioxidant activity/capacity measurement. 1. Classification, physicochemical principles, mechanisms, and in vitro assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64(5), 997–1027, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04739 (2016).

Prior, R. L., Wu, X., & Schaich, K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53(10), 4290–4302, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0502698, (2005).

Züst, T., & Agrawal, A. A. Trade-offs between plant growth and defense against insect herbivory: An emerging mechanistic synthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 38, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.005. (2017).

Harvey, J. A., Heinen, R., Gols, R., & Thakur, M. P. Climate change-mediated effects on plant-insect interactions: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 2921, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59873-y, (2020).

Smolko, A., Těšitel, J., & Fibich, P. Host specificity in parasitic plants: Current understanding and research perspectives. Plant Direct. 5(10), e00367. https://doi.org/10.1002/pld3.367, (2021).

Wink, M. Modes of action of herbal medicines and plant secondary metabolites. Medicines. 2(3), 251–286, https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines2030251. (2015).

Claros, P. Evaluación de la capacidad antioxidante total y contenido de polifenoles totales del Phaseolus vulgaris “Frijol”. Undergraduate Thesis, Universidad Nacional José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, Huacho, (2021).

López-Froilán, R., Hernández-Ledesma, B., Cámara, M., & Pérez-Rodríguez, M. Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of mixed fruit-based beverages: A new insight on the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Food Anal. Met. 11, 2897–2906, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-018-1259-1. (2018).

Pekal, A., & Pyrzynska, K. Evaluation of aluminum complexation reaction for flavonoid content assay. Food Anal. Met. 7, 1776–1782. (2014).

Rajurkar, N. S., & Hande, S. M. Estimation of phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of some selected traditional. Indian J. Pharm. Sci., 73, 146–151 (2011).

Sachett, A., Gallas-Lopes, M., Conterato, G. M. M., Herrmann, A., & Piato, A. Antioxidant activity by DPPH assay: In vitro protocol. Protocols.io. https://www.protocols.io/view/antioxidant-activity-by-dpph-assay-in-vitro-protocbtbpnimn. (2021).

Thaweesang, S. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic compounds of fresh and blanching banana blossom (Musa ABB cv. Kluai “Namwa”) in Thailand. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. . 639, 012047 (2019).

Kuskoski, E. M., Asuero, A. G., Troncoso, A. M., Mancini-Filho, J., & Fett, R. (2005). Aplicación de diversos métodos químicos para determinar actividad antioxidante en pulpa de frutos. Food Sci. Technol., 25, 726–732.

Tohma, H., Koksal, E., Kılıc, O., Alan, Y., Yılmaz, M. A., Gulcin, I., Bursal, E., & Alwasel, S. H. RP-HPLC/MS/MS analysis of the phenolic compounds, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Salvia L. species. Antioxidants. 5, 5040038 (2016).

Irakli, M., Skendi, A., Bouloumpasi, E., Chatzopoulou, P., & Biliaderis, C. G. LC-MS identification and quantification of phenolic compounds in solid residues from the essential oil industry. Antioxidants. 10(12), 2016, (2021).

Lluskal, T., Castillo, S., Villar-Briones, A., & Orešič, M. MZmine 2: Modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinform. 11, 395 (2010).

Cellier, G., Moreau, A., Chabirand, A., Hostachy, B., Ailloud, F., & Prior, P. (2015). A duplex PCR assay for the detection of Ralstonia solanacearum phylotype II strains in Musa spp. PLoS ONE. 10(3), e0122182.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Universidad de Las Fuerzas Armadas—ESPE for financial support.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de Las Fuerzas Armadas-ESPE, grant number CV-GNP-0066-2020, and the Institute of Biology Bucharest, Romanian Academy, RO1567-IBB06/2025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.M. conceived the project, managed the project, wrote the original version and revised the final manuscript; R.F.V.G., F.A.S.A., R.A.L.M. realized the formal analysis, M.A.N.P., J.E.C.C., A.R.C. realized the investigation; R.D.C. participated at the writing of the original version, editing and revised the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mihai, R.A., Vivanco Gonzaga, R.F., Silva Ayo, F.A. et al. Host-dependent variations in antioxidant activity, metabolic profile, and phenolic content of the parasitic plant Phoradendron nervosum Oliv.. Sci Rep 16, 1556 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27242-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27242-z