Abstract

Human brucellosis remains a major public health issue in endemic regions such as Iran. While climatic variables may affect transmission patterns, their role remains uncertain. This study analyzed long-term trends of human brucellosis in relation to climatic factors in Iran from 2000 to 2023. A time-series ecological design was applied using annual crude incidence rates (CIR) of brucellosis alongside climatic indicators including annual mean temperature (AMT), annual precipitation (AP), and the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). Correlation tests, linear regressions, and multivariate models were performed. The average CIR was 23.96 per 100,000. AMT showed an inverse correlation with CIR, while SPEI indicated a weak positive association. Precipitation was not significantly correlated. Multivariate models explained less than one-quarter of variance, and no climatic factor remained a significant predictor. Findings suggest that climatic variables alone have limited explanatory power for brucellosis trends in Iran, with socioeconomic, agricultural, and behavioral factors likely playing a much greater role. Rather than demonstrating a strong climate–disease link, this study highlights the complexity and potential insignificance of climatic influence on brucellosis incidence, underscoring the need for integrated One Health approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brucellosis, a bacterial zoonotic disease, is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the neglected tropical diseases. Despite its high prevalence in developing countries, it receives insufficient attention for prevention and control1. This disease has been reported in at least 170 countries, with its geographic scope expanding significantly due to global trade, increased human-animal interactions, and climate change2,3,4.

From a One Health perspective, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, brucellosis exemplifies how zoonoses are influenced by multifaceted factors5. Primarily caused by Brucella melitensis, Brucella abortus, and Brucella suis, human brucellosis is transmitted via unpasteurized dairy products or direct contact with infected animal tissues6,7,8,9,10. Socio-economic determinants, such as rural lifestyles, poverty, and traditional consumption habits, exacerbate transmission, particularly among high-risk groups like herders, slaughterhouse workers, veterinarians, men, the elderly, and rural children due to occupational exposure, weakened immunity, and dietary practices11,12,13,14.

This disease presents with flu-like symptoms including fever, fatigue, and sweating, and in chronic cases can lead to complications such as arthritis or myocarditis9,15. Epidemiologically, incidence is shaped by environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity, and precipitation) and socio-economic conditions (e.g., rural living and unpasteurized dairy consumption), often with a 2- to 4-month lag in human cases6,16,17.

Climate change further amplifies these risks by altering environmental variables like temperature, precipitation, and humidity, thereby modifying transmission patterns6,17,18,19,20. In endemic regions, integrating climate data with socio-economic and One Health frameworks is crucial for effective disease management5,21.

In Iran, brucellosis poses a significant public health challenge, especially in rural areas, with incidence rates ranging from 0.03 to over 200 cases per 100,000 population22,23,24. Prior studies indicate associations with climatic factors like reduced precipitation and moderate wind speed, though temperature effects are weaker25,26. These insights highlight the need for combined epidemiological and climate models to improve prediction and control18,27.

This study analyzes trends in the crude incidence rates (CIR) of human brucellosis in Iran from 2000 to 2023 and examines associations with climatic variables, including annual mean temperature (AMT), annual precipitation (AP), and the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). By incorporating a One Health lens and exploring both significant and non-significant associations, the findings aim to clarify the role of climatic factors while highlighting non-climatic drivers—such as socio-economic influences—and inform preventive policies and climate-informed forecasting models.

Methods

This time-series ecological study was conducted to investigate the relationship between climatic variables and the incidence of human brucellosis in Iran over the period from 2000 to 2023.

Data sources

Annual data on the number of confirmed human brucellosis cases were obtained from official reports issued by the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education for the years 2000 to 2023. These surveillance data cover the entire country and are compiled through the national portal of the Center for Communicable Diseases Management (ICDC) of the Ministry’s Deputy of Public Health (see Supplementary File S1: Brucellosis Data Source, Ministry of Health, Iran [in Persian])28. Data on climatic variables—including annual mean temperature (AMT), annual precipitation (AP), and the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)—were extracted from the Iran Climate Status Booklet, published in 2023 by the Iran Meteorological Organization, covering the same study period from 2000 to 2023 (see Supplementary File S2: Climate Status Report, Iran Meteorological Organization [in Persian, with English summary])29. Please note that the referenced source is in the Persian language.

Incidence rate calculation

The annual crude incidence rate (CIR) of human brucellosis was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed cases by the annual population of Iran—obtained from the World Health Organization database—and multiplying the result by 100,00030 .

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Non-normally distributed variables and those containing negative values were normalized through logarithmic transformation. Statistical analyses were conducted in three steps:

-

(1)

Correlation analysis The initial associations between climatic variables (temperature, precipitation, and SPEI) and the crude incidence rate (CIR) of brucellosis were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation test for normally distributed data and Spearman’s rank correlation for non-normal data.

-

(2)

Simple linear regression The individual effect of each climatic variable on CIR was examined using simple linear regression models.

-

(3)

Multivariate regression The simultaneous effects of climatic variables on CIR were analyzed using multiple regression models, with adjustments for potential confounding variables. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance values. Given the high correlation between annual precipitation (AP) and SPEI, additional regression models excluding AP were performed to evaluate the robustness of associations.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0), and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant31.

Data quality control

To minimize bias, both climatic and epidemiological data were sourced from reputable and reliable databases. Prior to analysis, the data underwent a thorough review and cleaning process to ensure their accuracy and validity.

Results

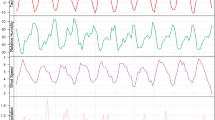

In the present study, the annual average crude incidence rate (CIR) of human brucellosis in Iran was 23.96 per 100,000 individuals (23.96 ± 5.75), with values fluctuating between 16.2 and 37.2 during the study period. The annual mean precipitation was 206.71 mm (standard deviation: 44.85), and the annual mean temperature was 18.17 °C (18.17 ± 0.50), ranging from a minimum of 17.2 °C to a maximum of 19.2 °C over the years studied. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) had an average value of -0.79 (± 0.62), with fluctuations between a minimum of -1.58 and a maximum of 0.75 (Table 1). Trends in CIR, AMT, AP, and SPEI are shown in Fig. 1 (panels a–d).

(a–d) Trends of CIR and climatic variables in Iran, 2000–2023. (a) CIR trend, (b) AMT trend, (c) AP trend, (d) SPEI trend. The time series graph of the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) from 2000 to 2023 demonstrates how climatic trends have influenced both drought and wet periods (d). This graph is presented without logarithmic transformation to preserve the actual temporal pattern of the drought index, allowing for a clearer understanding of the fluctuations in drought conditions over time.

Correlation results

Pearson correlation showed a significant negative association between CIR and AMT (r = − 0.439, p = 0.032). CIR–AP correlation was positive but not significant (r = 0.237, p = 0.265). Spearman’s rho between CIR and SPEI was ρ = 0.408 (p = 0.048). AMT was negatively correlated with AP (r = − 0.332, p = 0.113) and SPEI (r = − 0.365, p = 0.080). A very strong positive correlation was observed between AP and SPEI (r = 0.909, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Simple linear regression

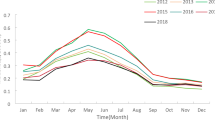

Univariate regression analyses showed that AMT was a significant predictor of CIR (B = − 5.021; p = 0.032; R² = 0.193), whereas AP exhibited a positive but non-significant association (B = 0.030; p = 0.265; R² = 0.056). Similarly, the log-transformed SPEI (SPEI_log) demonstrated a positive, though non-significant, relationship with CIR (B = 8.092; p = 0.081; R² = 0.132). Detailed coefficients for these simple models are provided in Supplementary Table S1, and corresponding scatterplots are illustrated in Fig. 2 (panels a–c).

Multivariate regression results (Effect of AMT, AP, and SPEI_log on CIR)

Model summary and analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The multivariate regression model explains 23.4% of the variance in CIR, with an adjusted R² of 0.119. The F-statistic of the model is 2.031, and the p-value is 0.142, indicating that the model is not statistically significant at the 0.05 level (Table 3).

Regression coefficients

The multivariate regression analysis showed that SPEI_log had a positive standardized coefficient (β = 0.213, p = 0.376), AMT had a negative standardized coefficient (β = -0.279, p = 0.278), and AP had a positive standardized coefficient (β = 0.141, p = 0.513) (Table 4). Although temperature showed a significant effect in univariate models, the overall explanatory power of climatic variables was low. The multivariate model explained less than 25% of the variance and was not statistically significant.

When precipitation (AP) was excluded from the multivariate model to address collinearity with SPEI, the remaining predictors (AMT and SPEI_log) did not achieve statistical significance (AMT: β = − 0.343, p = 0.147; SPEI_log: β = 0.181, p = 0.435). The model explained only 14.2% of the variance (adjusted R²), and the overall model was not statistically significant (F = 2.902, p = 0.077). These findings confirm that multicollinearity did not mask any substantial climatic effect, and that climatic variables had limited explanatory power for brucellosis incidence.

Discussion

This ecological study of human brucellosis in Iran from 2000 to 2023 revealed an average annual incidence rate of 23.96 ± 5.75 per 100,000 population, with the lowest rate in 2010 (16.2 per 100,000) and the highest in 2006 (37.2 per 100,000). Univariate analyses showed a significant negative correlation between annual mean temperature (AMT) and incidence, while the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) exhibited a significant positive correlation. However, none of the climatic variables— including annual precipitation—emerged as significant predictors in multivariate models, which explained less than 25% of the variance in incidence rates. These results underscore the limited and ambiguous influence of climatic factors on temporal trends in brucellosis.

Comparisons with prior studies

Our findings align with previous reports from Iran, where average incidence rates have ranged from 19.91 to 29.83 per 100,000 population13,32,33. The overall downward trend in incidence over the study period is consistent with studies documenting a decline from 26.83 per 100,000 in 2015 to 18.3 per 100,000 in 202032. This reduction may stem from enhanced animal control programs, greater public awareness, and improved surveillance systems22,34,35,36,37.

Factors influencing trends and incidence peaks

The observed downward trend could be driven by improvements in livestock management and public health measures. However, recent increases in incidence may reflect reduced adherence to preventive protocols, shifts toward small-scale non-industrial farming in urban and peri-urban areas post-COVID-19, antibiotic resistance, or heightened diagnostic sensitivity25,38,39,40. Peaks in incidence during 2006, 2015, 2020, and 2023 likely relate to non-climatic disruptions. In particular, the 2020 peak may be linked to COVID-19-related disruptions, including reduced zoonotic disease surveillance, altered food consumption patterns during lockdowns, and underreporting of infectious diseases overall. Studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic similarly affected reporting of diseases like tuberculosis and visceral leishmaniasis, suggesting parallel dynamics for brucellosis41,42.

Moreover, the intrinsic epidemiological cyclicity of brucellosis plays a critical role in incidence fluctuations. This cycle involves animal reservoirs (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats), horizontal transmission via aborted fetuses or contaminated milk, environmental persistence of Brucella influenced by factors like temperature and humidity, and spillover to humans through direct contact or unpasteurized products. Periodic peaks may occur independently of climate trends, driven instead by epidemiological factors such as vertical transmission in animals or lapses in reservoir control43,44.

Role of climatic factors

The negative correlation between AMT and brucellosis incidence is consistent with studies suggesting reduced Brucella survival at higher temperatures16,18. However, contrasting reports indicate that warmer temperatures in certain ranges may enhance bacterial metabolism and persistence17,45. The positive SPEI correlation implies indirect effects of drought, such as diminished vegetation leading to livestock congregation and heightened transmission risk17,46. Yet, discrepancies exist, with some Iranian studies showing inverse associations under quasi-drought conditions16. Precipitation results remain inconsistent, similar to other infectious diseases, where altered rainfall patterns have been linked to outbreaks of West Nile virus, diarrheal diseases, and waterborne infections47,48,49. Such parallels emphasize the need for nuanced investigations into indirect precipitation effects.

Overall, weak associations observed in simple regressions (e.g., AMT) did not persist in multivariate models, underscoring the limited explanatory power of climate alone. Strong multicollinearity between precipitation (AP) and SPEI was observed, so the analysis was repeated excluding AP; however, the associations remained non-significant, further indicating that climatic variables alone are insufficient to explain incidence trends.

Non-climatic drivers

Given the modest role of climate, socioeconomic, managerial, and behavioral factors likely dominate brucellosis epidemiology. Brucellosis disproportionately burdens low- and middle-income populations, such as farmers and herders, imposing economic strains through medical costs and livestock productivity losses. Rural and poorer areas face amplified challenges due to limited healthcare access, delayed care-seeking, and regional inequalities50,51,52. Effective control hinges on livestock management, including vaccination (e.g., RB51 for cattle, REV-1 for small ruminants), testing, culling infected animals, and surveillance22,53,54. Vaccination, while cost-effective, requires integration with sanitation, farmer education, and infrastructure to succeed, though occupational risks (e.g., needle-stick injuries) persist and can be mitigated with protective measures.

Human behaviors—shaped by cultural, gender, and social norms—further influence transmission. For example, gender roles in animal care or dairy processing affect exposure, while practices like consuming unpasteurized milk stem from limited awareness or economic constraints55,56. Interventions should therefore prioritize culturally sensitive education and protective practices.

One health framework

These findings reinforce the relevance of a One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health. Cross-sector collaboration is essential to expand livestock vaccination, strengthen surveillance, and promote food safety awareness5,21,57. Incorporating socioeconomic and behavioral data into such frameworks can provide a more complete picture of disease dynamics and improve control strategies.

Study limitations

First, the use of annual, national-level data precluded analyses of regional, seasonal, or lagged effects. Second, important climatic indicators (e.g., relative humidity, wind speed, sunshine hours) were unavailable. Third, strong collinearity between precipitation and SPEI undermined the stability of multivariate models. Fourth, underreporting and evolving diagnostic practices—particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic—may have biased incidence estimates. Finally, socioeconomic and behavioral drivers were not analyzed, limiting a holistic understanding of brucellosis epidemiology.

Conclusions

Climatic variables such as temperature and drought show some correlation with brucellosis incidence, but their influence appears weak, inconsistent, and overshadowed by socioeconomic, health, and epidemiological factors. The main strength of this study lies in demonstrating the absence of a strong unidirectional link with climate. Rising temperatures may even hinder transmission, contributing to the overall downward trend. Effective control strategies in Iran should therefore emphasize livestock management, socioeconomic interventions, and culturally tailored community engagement within a One Health framework.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lashley, F. Emerging infectious diseases at the beginning of the 21st century. Online J. Issues Nurs. 11 (2006).

Huang, S. et al. Risk effects of meteorological factors on human brucellosis in Jilin province, China, 2005–2019. Heliyon 10, e29611 (2024).

Liu, Z., Gao, L., Wang, M., Yuan, M. & Li, Z. Long ignored but making a comeback: a worldwide epidemiological evolution of human brucellosis. Emerg. Microbes Infections. 13, 2290839 (2024).

Marzaleh, M. A. & Ainvand, M. H. Strategic solutions to overcome emerging public health challenges with emphasis on vector-borne diseases (VBDs). EXCLI J. 23, 1353 (2024).

Ghanbari, M. K. et al. One health approach to tackle brucellosis: a systematic review. Trop. Med. Health. 48, 86 (2020).

WOAH. Brucellosis. https://www.woah.org/en/disease/brucellosis/ (2025).

Franc, K., Krecek, R., Häsler, B. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC public. Health. 18, 1–9 (2018).

Franco, M. P., Mulder, M., Gilman, R. H. & Smits, H. L. Human brucellosis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 7, 775–786 (2007).

McDermott, J., Grace, D. & Zinsstag, J. Economics of brucellosis impact and control in low-income countries. Revue Scientifique Et Technique (International Office Epizootics). 32, 249–261 (2013).

Wu, Z. et al. Human brucellosis and fever of unknown origin. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 868 (2022).

Alton, G. & Forsyth, J. Brucella. Medical Microbiology, 4th edn (Churchill Livingstone, 1996).

Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C. & Blasco, J. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. des. Epizoot. (2013).

Golshani, M. & Buozari, S. A review of brucellosis in iran: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis, control, and prevention. Iran. Biomed. J. 21, 349 (2017).

Pereira, C. R. et al. Occupational exposure to Brucella spp.: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008164 (2020).

Sahar, M. J. Current Topics in Zoonoses (ed Rodriguez-Morales Alfonso, J.) (IntechOpen, 2024).

Faramarzi, H., Nasiri, M., Khosravi, M., Keshavarzi, A. & Rezaei Ardakani, A. R. Potential effects of Climatic parameters on human brucellosis in Fars Province, Iran, during 2009–2015. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 44, 465–473. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijms.2019.44968 (2019).

Wu, D. et al. Risk effects of environmental factors on human brucellosis in Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, 2014–2023. Sci. Rep. 15, 2908 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. Driving role of Climatic and socioenvironmental factors on human brucellosis in china: machine-learning-based predictive analyses. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 12, 87–100 (2023).

Jäger, J. & O’Riordan, T. In the Politics of Climate Change 1–31 (Routledge, 2019).

van Dalen, H. P. & Henkens, K. Population and climate change: consensus and dissensus among demographers. Eur. J. Popul. 37, 551–567 (2021).

Ghai, R. R. et al. A generalizable one health framework for the control of zoonotic diseases. Sci. Rep. 12, 8588 (2022).

Dadar, M., Alamian, S. & Zowghi, E. Comprehensive study on human brucellosis Seroprevalence and Brucella species distribution in Iran (1970–2023). Microb. Pathog. 198, 107137 (2025).

Pordanjani, S. R. et al. Geographical epidemiology and Temporal trend of brucellosis in Iran using geographic information system and join point regression analysis: A 10-year study. Iran. J. Public. Health. 53, 1446–1456 (2024).

Zeinali, M., Doosti, S., Amiri, B., Gouya, M. M. & Godwin, G. N. Trends in the epidemiology of brucellosis cases in Iran during the last decade. Iran. J. Public. Health. 51, 2791 (2022).

Kanannejad, Z. et al. Effect of Human, Livestock Population, Climatic and Environmental Factors on the Distribution of Brucellosis in Southwest Iran 35 (2019).

Mohammadian-Khoshnoud, M., Sadeghifar, M., Cheraghi, Z. & Hosseinkhani, Z. Predicting the Incidence of Brucellosis in Western Iran Using Markov Switching Model 14 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. A systematic analysis of and recommendations for public health events involving brucellosis from 2006 to 2019 in China. Ann. Med. 54, 1859–1866 (2022).

Center for Infectious Disease Control, t. M. o. H., Treatment, and Medical Education of Iran. brucellosis_situation. https://icdc.behdasht.gov.ir/brucellosis_situation/%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%B9%DB%8C%D8%AA-%D8%A8%DB%8C%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B1%DB%8C-%D8%AA%D8%A8-%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84-1401 (2023).

Ministery Of Roads And Urban Development Of & Iran, I. M. O. وضعیت اقلیم کشور در سال 1402 (سالنامه شمسی 1402). http://wheatiran.ir/1403/06/05/%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%B9%DB%8C%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%82%D9%84%DB%8C%D9%85-%DA%A9%D8%B4%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84-1402-%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%87-%D8%B4%D9%85%D8%B3%DB%8C-1402 (2024).

Nations, U. UN Population Division Data Portal. https://population.un.org/dataportal/home?df=419414c7-0ba7-41b3-aec7-c2e2debcf178 (2025).

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp, 2019).

Delam, H., Keshtkaran, Z., Rezaei, B., Soufi, O. & Bazrafshan, M. R. Changing patterns in epidemiology of brucellosis in the South of Iran (2015–2020): based on Cochrane-Armitage trend test. Annals Global Health. 88, 11 (2022).

Pordanjani, S. R. et al. Spatial epidemiology and Temporal trend of brucellosis in Iran using geographic information system (GIS) and join point regression analysis: an ecological 10-Year study. Iran. J. Public. Health. 53, 1446 (2024).

Ghugey, S. L., Setia, M. S. & Deshmukh, J. S. The effects of health education intervention on promoting knowledge, beliefs and preventive behaviors on brucellosis among rural population in Nagpur district of Maharashtra state, India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11, 4635–4643 (2022).

Novitsky, A., Pleshakova, V., Trofimov, I., Alekseeva, I. & Lorengel, T. Areas of concern of brucellosis specific prevention. Adv. Anim. Veterinary Sci. 7, 94 (2019).

Singh, B. B., Kostoulas, P., Gill, J. P. & Dhand, N. K. Cost-benefit analysis of intervention policies for prevention and control of brucellosis in India. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006488 (2018).

Zhang, N. et al. Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Prev. Vet. Med. 160, 105–115 (2018).

Charypkhan, D. & Rüegg, S. R. One health evaluation of brucellosis control in Kazakhstan. PLoS One. 17, e0277118 (2022).

Elbehiry, A. et al. Proteomics-based screening and antibiotic resistance assessment of clinical and sub-clinical Brucella species: an evolution of brucellosis infection control. PLoS One. 17, e0262551 (2022).

Narimisa, N., Razavi, S. & Masjedian Jazi, F. Risk factors associated with human brucellosis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 24, 403–410 (2024).

Belleudi, V. et al. Direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 10, 2388 (2021).

Spaziante, M. et al. Interrupted time series analysis to evaluate the impact of COVID-19-pandemic on the incidence of notifiable infectious diseases in the Lazio region, Italy. BMC Public. Health. 25, 132 (2025).

Bagheri, H. et al. Forecasting the Monthly Incidence Rate of Brucellosis in West of Iran Using Time Series and Data Mining from 2010 to 2019 15 (2020).

Mirnejad, R., Jazi, F. M., Mostafaei, S. & Sedighi, M. Epidemiology of brucellosis in iran: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis study. Microb. Pathog. 109, 239–247 (2017).

Ahmadkhani, M. & Alesheikh, A. A. Space-time analysis of human brucellosis considering environmental factors in Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Disease. 7, 257–265. https://doi.org/10.12980/apjtd.7.2017D6-353 (2017).

Arotolu, T. E. et al. Modeling the current and future distribution of brucellosis under climate change scenarios in Qinghai lake basin, China. Acta Vet. 73 (2023).

Baharom, M., Ahmad, N., Hod, R., Arsad, F. S. & Tangang, F. The impact of meteorological factors on communicable disease incidence and its projection: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 11117 (2021).

Horn, L. M. et al. Association between precipitation and diarrheal disease in Mozambique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15, 709 (2018).

Lorenzon, A. et al. Effect of climate change on West nile virus transmission in italy: A systematic review. Public Health Rev. 46, 1607444 (2025).

Alusi, P. M. Socio-cultural and Economic Risk Factors for Human Brucellosis in Lolgorian Division, TransMara District (University of Nairobi, 2014).

Méndez-González, K. Y. et al. Brucella melitensis survival during manufacture of ripened goat cheese at two temperatures. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 1257–1261 (2011).

Rubach, M. P., Halliday, J. E., Cleaveland, S. & Crump, J. A. Brucellosis in low-income and middle-income countries. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 26, 404–412 (2013).

Alamian, S., Bahreinipour, A., Amiry, K. & Dadar, M. The control program of brucellosis by the Iranian veterinary organization in industrial dairy cattle farms. Arch. Razi Inst. 78, 1107 (2023).

Elbehiry, A. et al. The development of diagnostic and vaccine strategies for early detection and control of human brucellosis, particularly in endemic areas. Vaccines 11, 654 (2023).

Baron-Epel, O., Obeid, S., Kababya, D., Bord, S. & Myers, V. A health promotion perspective for the control and prevention of brucellosis (Brucella melitensis); Israel as a case study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010816 (2022).

Kulabako, C. T. et al. Gender and cultural aspects of brucellosis transmission and management in Nakasongola cattle corridor in Uganda. PloS One. 20, e0320364 (2025).

Shafique, M. et al. Traversed dynamics of climate change and one health. Environ. Sci. Europe. 36, 1–18 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KA and MH designed and conceptualized the study. AS and OE gathered the data and MH and KA analyzed them. MH, KA, AS and OE drafted the manuscript. All the authors participated in writing the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study utilized officially published, aggregated data and did not involve human participants or the collection of personal data. Therefore, formal ethical approval was not required. Clinical trial number: not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamyali-Ainvand, M., Eilami, O., Soltani, A. et al. Ecological study of human brucellosis in Iran from 2000 to 2023 and the limited role of climatic factors. Sci Rep 15, 43459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27249-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27249-6