Abstract

This study presents a novel approach for the prediction of daily pan evaporation (Evp) based on identifying an optimal combination of model inputs. The Kardeh Dam catchment area in northeastern Iran, where significant evaporation occurs, was investigated in this study. Initially, an appropriate combination of inputs was identified through the gamma test and genetic algorithm (GTGA). Using the ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD), each input data was converted into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), which were then used as input to long short-term memory (LSTM) and convolutional neural network (CNN) models. The model inputs considered in this work for predicting pan evaporation included maximum and minimum temperature, precipitation, and evaporation in earlier stages. Each input variable was transformed into nine IMFs, simplifying the complex pattern of input variables and leading to improved performance of both CNN and LSTM models. The prediction results using the CNN exhibited RMSE, MAE, and SI values equal to 0.33 mm, 0.24 mm, and 0.06, respectively. Using the LSTM, these values were equal to 0.043 mm, 0.11 mm, and 0.016, respectively. The proposed methodology can be applied in various regions for improved evaporation prediction, offering decision-makers and researchers a clearer understanding of future evaporation trends to effectively manage water resources and prevent wastage of water, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In arid and semi-arid regions, water availability, control, and management for various purposes are of paramount concern1,2. The reduction in water quantity also affects water quality unfavorably3. Evaporation is a process that renders a large portion of water unavailable. The increase in evaporation rate can be considered an important indicator of global warming4,5. Evaporation plays a crucial role in the implementation of water resources strategies and the design of irrigation systems6. Reliable prediction of evaporation is essential for hydrological and water resources managers, enhancing water use and water balance7,8. Diverse methodologies have been used for this prediction, including energy balance, water balance, mass transfer, the Penman method, and pan evaporation7,9,10. The most common method for measuring evaporation is the pan evaporation method11,12. However, this method is a time-consuming process, influenced by meteorological variables such as wind speed and vapor pressure. Evaporation pans cannot be installed everywhere because, in addition to the high installation costs, they require skilled maintenance and management13. Indirect techniques involve determining pan evaporation (Evp) using meteorological data and physical concepts such as volume and energy storage, which require careful adjustment based on weather and climate and necessitate specialized tools and skilled labor14. On the other hand, using these models for regions with different climates may yield varying results, requiring calibration15,16.

In situations where techniques for calculating hydrological variables face limitations, the use of new data-driven models can be useful2,13,17. The growing trend of such methods based on artificial intelligence, and more particularly, deep learning, has had a profound impact on the field of time series forecasting18,19. Long short-term memory (LSTM) and convolutional neural networks (CNN) are deep learning models that exhibit great potential in generating nonlinear mapping rules between intricate time series patterns20,21. They are specifically designed to learn linear and nonlinear patterns to solve regression problems22,23. These models have been successfully used to forecast groundwater level24,25, drought26,27, evaporation13,28, river flow29,30, and precipitation31. The presence of complex patterns in the input data can impact the performance of these models. This is particularly evident in LSTM, which may struggle in capturing the pattern of data features in nonlinear time series forecasting32. Similarly, CNN models sometimes do not perform well in predicting time series with one-dimensional features33. To address such challenges, the empirical mode decomposition (EMD), introduced by Huang et al.34, can be used for analyzing data characterized by noise. The EMD technique is self-consistent, making it preferable to other traditional methods35. However, there are various challenges when using the EMD to decompose data. For example, the intrinsic mode functions (IMF) obtained from the EMD often suffer from modal mixing, resulting in incorrect decomposition36.

The ensemble-EMD (EEMD) has been proposed, incorporating white noise decomposition to address the modal mixing issue observed in EMD. EEMD offers several advantages over EMD: it effectively separates oscillations by adding white noise, resulting in more accurate IMF components; the added noise helps dampen measurement noise, making the decomposition more resilient to noise contamination; and it provides more accurate time-frequency analysis, leading to better insights from the decomposed IMFs.

The EEMD also effectively suppresses modal mixing and improves the decomposition quality37. Despite some research on combining EEMD with machine learning models for various applications, such as the research by Hung et al.38 on enhancing the performance of wind speed prediction using LSTM and GPR models, Wu et al.39 on oil price forecasting with LSTM-EMD, Tian et al.40 on runoff forecasting using EEMD-artificial neural networks (ANN), Liao et al.41 on utilizing EEMD-ANN for runoff forecasting, and Liu et al.42 on employing EEMD-autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) in urban runoff forecasting, there is still a need for more comprehensive research on EEMD, particularly for meteorological and hydrological prsdiction.

In arid and semi-arid regions like Iran, evaporation from the land surface is significant that has a devastating impact on local water resources. Daily pan evaporation (Evp) prediction in such regions is considered an effective step in managing water resources and reserves. Despite significant advances in machine learning models, limited research has been conducted on Evp prediction. Selecting effective variables among available features is one of the main challenges for introducing an appropriate combination of input variables for the prediction tasks. Reducing or eliminating noise in time series is another challenge in increasing the performance of time series prediction. The current research thus, aimed to: (1) use the gamma test and genetic algorithm (GTGA) to select the most effective input variables and create an appropriate combination of inputs to predict Evp, (2) utilize the EEMD method to reduce noise and eliminate fluctuations in the input data time series, and (3) predict Evp in a typical semi-arid region using two deep learning models, CNN and LSTM. The proposed method can improve the performance of Evp using noise removal and deep learning methods. Moreover, this study is an effort to find the least available meteorological information for the prediction task.

Study area

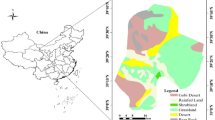

The Kardeh Dam watershed, located in northeastern Iran and north of Mashhad City, is one of the most important sub-basins of the Ghare-Ghom River (Fig. 1a), covering an area of approximately 540 km2. This basin is mountainous with relatively steep slopes, reaching a maximum elevation of 2948 m and a minimum elevation of 1291 m at the Kardeh Dam site. The average elevation of the sub-basin is 2014 m above sea level (Fig. 2b), which depicts its elongated rectangular shape. The predominant geology of the area consists of limestone formations. The soil in the region is relatively diverse, with Calcixerepts soil being the most prevalent and Ochric soil having the lowest coverage. Economic activities in the area primarily involve animal husbandry and agriculture, highlighting the region’s heavy reliance on water resources. Therefore, accurate prediction of evaporation rates is crucial for effective water resource management in the region. The average annual evaporation rate in this region is 100 mm, while the average annual rainfall ranges from 350 mm in the plain to 640 mm in the highlands. The construction of the Kardeh Dam in 1987 marked a significant development in the area, with its primary objectives being to provide water for agricultural lands downstream of the dam and to supply water to the city of Mashhad.

Location of the study area, (a) Location of the Ghare-Qom sub-basin, (b) Location of the Kalat Naderi study area (Kardeh station)—ArcMap 10.8 (https://www.arcgis.com/index.html).

Materials and methods

The model input variables for the prediction of pan evaporation (Evp) included maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation, and Evp values one to three days earlier [Evp(n-1), Evp(n-2), and Evp(n-3)]. Optimal combination of input variables was determined using the GTGA method. Each input variable was individually preprocessed by the EEMD and converted into IMFs. Subsequently, the IMFs were used as input to the CNN and LSTM models. The Evp was modeled using two scenarios: before and after data preprocessing by the EEMD to investigate the performance of EEMD (Fig. 2). The models’ performance was evaluated using various error evaluation criteria and graphical representation, such as Taylor’s diagram, violin diagram, and ridgeline plot.

Data collection

Figure 3 illustrates the daily changes in the input variables between 2015 and 2017. Maximum and minimum temperatures exhibit sinusoidal patterns, with temperatures peaking above average in the first six months of the year and dropping below average in the second half. The maximum temperature reaches 40.0 °C, while the lowest temperature hovers around − 20.0 °C (Fig. 3b). The fluctuations in both temperature values closely mirror the changes in Evp, suggesting a strong correlation among them. Figure 3(c) displays the daily precipitation changes during the specified period, alongside the Evp. Unlike temperature, precipitation fluctuations are not consistent with the changes in Evp. Generally, when precipitation levels are high, evaporation values reach their minimum, indicating an inverse relationship between precipitation and Evp.

The heatmap of correlation between input and output variables shows that precipitation has an inverse relationship with temperature and Evp (Fig. 4). The correlation coefficient between precipitation and Evp is -0.106, indicating a low relationship. The correlation with Evp(n-1) and Evp(n-2) is slightly higher (-0.140 and − 0.135, respectively). The highest correlation between input variables and the Evp is Evp(n-1), with a correlation coefficient of more than 0.95. Evp(n-2) has a correlation of about 0.946 with the output, indicating a strong dependence of evaporation on the values of previous days. Among the variables studied, only precipitation has a weak correlation with the Evp. The correlation coefficient of maximum and minimum temperature with the Evp is greater than 0.8, suggesting they can be effective in the prediction task. When compiling various input scenarios, a total of 2n-1 scenarios can be created. In this study, considering the six input variables (n = 6), 63 input scenarios can be generated. The GTGA was used to finding the most efficient combination of model inputs.

Gamma test and genetic algorithm

The gamma test (GT) is a nonlinear optimization model that can be utilized to analyze an optimal combination of various inputs for modeling and creating a stable model with minimal error43. This test can also be used to some extent to estimate the portion of the output data variance that cannot be derived from the input data by creating a stable and smooth model. In the GT, each input scenario consists of a row of zeros and ones, known as a mask. Zero values indicate the non-participation of an input variable in the model, while ones indicate the participation of that variable in the input scenario43. The selection of the best mask as the optimal input scenario in the GT is determined based on the calculation of the gamma statistic (Γ) and index (Vratio). This process is facilitated by the genetic algorithm (GA). To identify the best mask, all meaningful combinations (masks) of the input data should be manually created to calculate the Γ and Vratio. The closer the Γ and Vratio are to zero, the more suitable the mask is for modeling. Conversely, if they are closer to one, it indicates a significant random error in modeling, and creating a model based on selected masks diminishes model accuracy. The GA was employed in this work to determine appropriate combination values in conjunction with the GT. The implementation of the GTGA was conducted using the Gamma Win software. The population size used for the GA was 100. Additionally, the crossover rate and mutation rate were set to 0.5 and 0.05, respectively.

Deep learning models

LSTM, a variant of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), has recently gained popularity for its superior ability to handle sequential data compared to conventional neural networks. Unlike typical RNNs, LSTM networks incorporate memory cells and gating mechanisms at each node, allowing them to retain, adjust, prioritize, or discard information over extended sequences44. The operations of LSTM cells are detailed in Eq. (1) to (5);

where it, f, ot, ct, and mt represent the input gate, forget gate, output gate, the current cell state, and the memory at time t, respectively. LSTM networks capture long-term dependencies through three main gates—forget, input, and output—working alongside the cell state. The forget gate removes unnecessary information, the input gate incorporates new relevant data, and the output gate determines what information should be passed forward. The gate-based mechanism enables LSTMs to preserve critical information over extended time periods, making them well-suited for time series forecasting tasks. In this study, a uniform, sequential LSTM model was developed for multi-step forecasting of pan evaporation. The univariate model relies solely on historical values of the target variable to recursively forecast future values. The architecture comprises four layers: a sequence input layer, an LSTM layer, a fully connected layer, and a regression layer. The input and fully connected layers are aligned with the number of input and output variables, respectively, while the LSTM layer contains the hidden units. The regression layer handles the prediction task. Among these, the sequence input and LSTM layers are critical for enabling the network to process and learn dependencies in time series data. A detailed description of the model can be found in45. The model was used to predict the Evp, with hyperparameters optimized through trial and error. The setup included 20 neurons, three hidden layers, and 1000 training iterations.

CNNs are available in one-, two-, and three-dimensional forms, with the two-dimensional model being most commonly applied to image classification tasks. The one- and three-dimensional variants are also widely used in various engineering applications. Despite their dimensional differences, all CNN models share core characteristics and follow a consistent methodology. CNNs differ from traditional neural networks by incorporating multiple layers, localized connections, weight sharing, and data fusion. Typically, a CNN architecture includes convolutional layers (CLs), activation layers, pooling layers (PLs), and rectified linear unit (ReLU) layers46. The convolutional layer extracts spatial relationships and patterns from the input data47. The pooling layer, often referred to as the fusion layer, reduces dimensionality through downsampling, which helps prevent overfitting before the data reaches the fully connected layer48. Finally, the fully connected layer combines all features to generate the output46,47. Figure 5 illustrates a basic CNN layout tailored for regression tasks. For the Evp prediction model, hyperparameters were tuned by setting 25 neurons, 15 intermediate layers, 35 hidden layers, and 1500 training iterations.

The EEMD is a mathematical technique designed to extract nonlinear and non-stationary components from raw data49. It involves preprocessing time series data by breaking it down into a small number of oscillatory components, each corresponding to a specific local time scale50. These oscillatory components are known as IMFs. EMD, the foundational method behind EEMD, is a self-adaptive time-frequency analysis tool that decomposes signals into a combination of slow and fast oscillations, each with a zero mean, represented as IMFs34,49. Each IMF captures a basic oscillatory pattern, offering a more flexible representation than a traditional harmonic function. The steps of this method are summarized in six steps. In the first step, all extrema, containing local maximum and minimum points of the given time series (y(t)), are detected. In step 2, the obtained local maximum points are used to create an emax(t) on the upper envelope, and also all minimum points are used to obtain emin(t) of the lower envelope by spline interpolation. In step 3, the average of m(t) for the two envelopes is calculated using

In step 4, m(t) is subtracted from the IMF-generated data.

In the next step, if h(t) satisfies the predefined stopping criterion, then it is designated as the first IMF. In step 6, once the residual either forms a uniform trend or includes a local maximum and minimum point, the shifting process is halted, indicating that no more IMFs can be extracted. The original signal can be reconstructed after this shifting procedure by adding together the IMF and the residual using

The EEMD was implemented in the R programming language, where various input variables were divided into different IMFs. Figure 6 provides an example of EEMD application and analysis of the changes in precipitation (RStduio programing). In this example, approximately nine IMFs are formed, with residual values specified at the end. It is also noted that noise separation reaches a relatively constant value by the end of IMF9. The range of changes in IMF1 was between − 5.0 and 5.0 mm, while IMF9 ranged from 3.0 mm to 15.0 mm.

Performance evaluation criteria

The performance evaluation criteria were utilized to assess the models’ performance. Two types of criteria are commonly utilized. The first type is numerical criteria, including RMSE (Eq. 9), MAE (Eq. 10), the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) (Eq. 11), normal root mean square error (NRMSE) (Eq. 12), MSE (Eq. 13), SI (Eq. 14), and correlation coefficient (CC) (Eq. 15). The second type involves graphical representations, such as Taylor’s diagram, violin diagram, data scatter diagram, and ridgeline plot that were used in this study51.

Results

The proposed GTGA included all input variables in the optimal input scenario, except for Evp(n-3), which was determined based on the Γ (1.2615) and Vratio (0.0422) criteria (Fig. 7). The decline in the Γ and Vratio can be seen in the figure, where both variables reached their lowest value in the 62nd model. The final mask was 111,011, representing the inclusion of maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation, Evp(n-1), and Evp(n-2) in the input scenario.

Figure 8 shows the number of IMFs produced for each variable, in which eight IMFs were produced for the minimum temperature. The trend of changes at the beginning of the IMF is intense and eventually reaches a value with much less fluctuation. For other variables, the number of IMFs produced and the residual value are shown in Fig. 8, included nine IMFs for precipitation, maximum temperature, and Evp. Their fluctuation was as intense as the minimum temperature at the beginning of the produced IMFs, which eventually approached an almost constant value in the final IMF.

To investigate the performance of the EEMD, both the raw data of input variables and their IMFs were considered to predict the EVp. Table 1 presents the error evaluation criteria for the LSTM and CNN models, as well as their hybrid algorithms with EEMD. The NSE for both groups in all models falls between 0.92 and 0.99. In the simulation of training data, the single LSTM model (with MSE, RMSE, MAE, NSE, NRMSE, and SI of 0.36 mm, 0.60 mm, 0.50 mm, 0.988, 0.077, and 0.107, respectively) outperformed the CNN model (with MSE, RMSE, MAE, NSE, NRMSE, and SI of 1.51 mm, 1.23 mm, 0.87 mm, 0.950, 0.156, and 0.217, respectively). However, when simulating the test data, the CNN model performed better (MSE, RMSE, MAE, NSE, NRMSE, and SI of 1.44 mm, 1.20 mm, 0.86 mm, 0.949, 0.155, and 0.213, respectively). Utilizing the EEMD in the structure of both models increased their prediction performance. In the EEMD-CNN hybrid model, the evaluation criteria for the test data (MSE, RMSE, MAE, NSE, NRMSE, and SI of 0.75 mm, 0.87 mm, 0.62 mm, 0.972, 0.113, and 0.155, respectively) demonstrated its better performance than the EEMD-LSTM model (with MSE, RMSE, MAE, NSE, NRMSE, and SI of 2.01 mm, 1.42 mm, 1.03 mm, 0.935, 0.175, and 0.230, respectively).

According to Fig. 9, the position of the observational data (horizontal axis) and the predicted values by the models (vertical axis) relative to the y = x line shows that, except for LSTM, they are closely aligned with the line and exhibited less dispersion around the y = x line. In the LSTM, the correlation coefficient was 0.966, the lowest among the models used. It can also be seen from the LSTM graph that the maximum values (between 15 and 20 mm) were consistently estimated between 10 and 15 mm. As a result, the data trend at the end of the graph deviated significantly from the y = x line. In contrast, the EEMD-LSTM hybrid model had a correlation coefficient of 0.979, showing much less dispersion of the data compared to LSTM. The highest correlation of 0.989 was observed for the EEMD-CNN. Additionally, this model showed a higher density of points along the y = x line, indicating limited data dispersion. This is an improvement over the CNN results, which had a correlation of 0.976.

The performance of the CNN and LSTM models with and without using EEMD was evaluated using violin plots. Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of predictions and observations. According to the figure, the median of the observational data is greater than 5 mm and around 6 mm. The CNN algorithm estimated values around the median to some extent, similar to the observational data, and the same trend was observed in the EEMD-CNN hybrid model. In contrast, the LSTM model simulated lower values. However, the EEMD improved the LSTM simulation, resulting in values similar to the observations. The shape of the four models in the first quartile range is more elongated compared to the observations. The LSTM models estimated peak data to be less than the observations, but this discrepancy was largely mitigated in the EEMD-LSTM model.

Further, the Joy plots (Fig. 11a) show that the density of data in the LSTM model has a large elongation in the range of 0.0 to 4.0 mm. However, in the EEMD-LSTM model, the data in the high-density range are more consistent with the observations. This positive performance was also observed in the CNN and EEMD-CNN models. The EEMD-CNN has a better fit with the observations. Overall, the distribution shape of data for the EEMD-CNN and EEMD-LSTM models in the range of 5.0 to 15.0 mm closely resembles the observations. Generally, the performance of the hybrid models was better than that of the single models. In Taylor’s diagram (Fig. 11b), three indices of correlation coefficient, RMSE, and standard deviation determine the spatial location of the simulated data by the models. The figure illustrates that the locations of all models, except for LSTM, are close to each other and align with the observational data. Moreover, the EEMD-CNN exhibited the best performance among all the methods used, with a correlation coefficient, RMSE, and standard deviation of 0.997, 0.81 mm, and 5.2 mm, respectively.

Figure 12 displays the time series of simulated Evp data for each model, along with the uncertainty band (gray area) at the daily time step. The results clearly indicate that the Evp base values consistently have a larger uncertainty band, suggesting that within the range of 0 to 5 mm/day, uncertainty can be significant. Conversely, values exceeding 10 mm consistently have a smaller uncertainty band. However, some simulated values have surpassed the allowable uncertainty band, particularly in the range of 15 mm to 20 mm, indicating greater uncertainty. Furthermore, the estimated values from the LSTM model at maximum values in certain steps, such as between samples 1100 and 1250, as well as between 1550 and 1650, have consistently been less accurate. This shortcoming has been addressed in the EEMD-LSTM model. Nonetheless, the comparison of simulated and actual trends and changes in the graphs reveals that most models effectively capture trends and remain within the acceptable uncertainty band.

Discussion

Despite the variety of predictive models available for evaporation prediction, further research is still necessary to achieve accurate and promising results. In this study, the EEMD was utilized to enhance the accuracy of individual deep learning models. The results indicated that the combination of EEMD with the CNN and LSTM was effective and appropriate. These findings are partially supported by the results of previous studies by Huang et al.52 on runoff prediction using EEMD-LSTM and Wu et al.39 in oil price prediction using EEMD-LSTM. However, there have been limited studies on EEMD-CNN. One of these research studies is Singh and Kumar53. Comparing the results of the current study with similar ones in the field suggests that the EEMD generally enhances model performance. This enhancement has also been observed by Liu et al.29 on the use of EEMD-ARIMA and EEMD-SVM in predicting urban water consumption, as well as the use of EEMD-ANN in runoff estimation40 and evapotranspiration prediction54.

To a limited extent, some research, including the research of Sezen55 on examining the performance of EEMD and random forest in predicting the Evp, has indicated appropriate performance of such approaches. Along with the current research, these investigations reveal the need to use noise reduction methods in hydrological time series problems since hydrological data always contain much noise that have negative effects on the forecast results. Therefore, the use of such approaches in other similar fields is recommended.

The results of this research showed that the EEMD performs better in improving CNN compared to LSTM simulations. Although the use of EEMD improves the results, it also increases the complexity of the input structure and the number of inputs. For example, in this research, the number of inputs was increased from 6 to 54 by considering the EEMD. This results in higher computational complexity in predictions. It should be noted that when the number of input variables is high (more than 10), the performance of the prediction models may be adversely affected. Other methods, such as CEEMDAN, VMD, and SSA, can be used for either reducing or eliminating noise in time series. It is recommended that such methods be evaluated in future research and compared with the results of this study to determine the most appropriate noise removal method in the field of Evp prediction.

The GTGA was suggested to optimize input variables and reduce unnecessary input features, thereby preventing complexity. Utilizing the GTGA suggested a suitable input scenario, which decreased the number of calculations, ultimately reducing processing time and cost. In addition, based on GTGA, the number of appropriate delays for the prediction task can also be estimated. In this study, the results showed that the data of evaporation one and two days earlier can be effective in Evp prediction. The data from three days earlier and before that might have much less impact. Therefore, this method can be a suitable approach for selecting effective features and combining the most appropriate features to create a reliable input scenario.

A delimitation of this study is the lack of information on variables such as wind speed, sunshine hours, relative humidity, solar radiation, and number of sun days, which can impact the Evp prediction results. Instead, the least possible data were used for prediction. In future research, considering such information would be beneficial. However, the uncertainty of results indicated that the output of the models did not exhibit significant errors. It was noted that the maximum values consistently fell within the critical range of allowable uncertainty. This underscores the importance of thorough attention to data collection and examination of uncertainty and errors in data collection. The results of CNN were generally better than those of LSTM and could simulate the Evp with less uncertainty. This is one of the notable findings of the present study, as compared to previous research. For example, Deng et al.56 conducted research on the use of CNN and LSTM in runoff prediction.

Despite encouraging results of deep learning models, these methods have limitations. For example, these methods may not perform well in situations where there is not an appropriate number of data in the time series. These methods normally require a large number of data samples that might not be available for some areas or data collection programs. The compared two methods are complex and within black-box models that require advanced simulation techniques and require relatively powerful hardware compared to conventional methods57,58. Thus, the CNN and LSTM deep learning methods require professional users. Their hyperparameter tuning and sensitivity to data are among other limitations that have a significant impact on the accuracy of time series prediction.

Conclusions

This study investigated methods for identifying optimal input variables and improving the performance of Evp prediction in arid and semi-arid regions. The GTGA was utilized to choose appropriate input scenarios, and data preprocessing was conducted using the EEMD method, which transformed complex raw input data into simpler patterns through IMFs and residuals. Subsequently, two deep learning methods, CNN and LSTM, were employed to forecast Evp in the Kardeh River basin. The use of the GTGA led to the selection of maximum and minimum temperature, precipitation, and evaporation data one- and two-day earlier as model inputs. By applying the EEMD, each input variable was transformed into nine IMFs, enhancing the model’s performance. The CNN provided Evp predictions with the RMSE, MAE, and SI values of 0.06 mm, 0.24 mm, and 0.33, respectively. Similarly, in the LSTM model, these values were 0.016 mm, 0.14 mm, and 0.042, respectively. The results of Taylor’s diagram, violin graph, and ridgeline plots indicated the high performance of the EEMD-CNN and EEM-LSTM hybrid models compared to the CNN and LSTM. Among the models, EEMD-CNN demonstrated the most appropriate performance. The forecast values fell within an acceptable range of uncertainty. However, the maximum predicted values always exhibited partial uncertainty, which necessitates further investigation. Considering variables such as wind speed can enhance the performance of the model, which were not taken into account in this study due to insufficient information. Such variables along with other factors like absolute minimum and absolute maximum temperature, can improve the results in future research. Utilizing the method introduced in this work in other research areas, as well as comparing it with other machine learning techniques, will make this approach more comprehensive.

Data availability

Data available on request from the corresponding authors.

References

Milan, S. G., Roozbahani, A. & Banihabib, M. E. Fuzzy optimization model and fuzzy inference system for conjunctive use of surface and groundwater resources. J. Hydrol. 566, 421–434 (2018).

Bahmani, M. J. et al. Development of a new hybrid model to enhance streamflow Estimation using artificial neural network and reptile search algorithm. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 6098 (2025).

Pereira, L. S., Oweis, T. & Zairi, A. Irrigation management under water scarcity. Agric. Water Manage. 57 (3), 175–206 (2002).

Dai, A., Zhao, T. & Chen, J. Climate change and drought: a precipitation and evaporation perspective. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 301–312 (2018).

Su, T., Feng, G., Zhou, J. & Ye, M. The response of actual evaporation to global warming in China based on six reanalysis datasets. Int. J. Climatol. 35 (11) (2015).

Uddin, J., Smith, R., Hancock, N. & Foley, J. P. Droplet evaporation losses during sprinkler irrigation: an overview. In Australian Irrigation Conference and Exibition 2010: Proceedings (2010).

Kayhomayoon, Z. et al. Prediction of evaporation from dam reservoirs under climate change using soft computing techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (10), 27912–27935 (2023).

Wang, K. & Dickinson, R. E. A review of global terrestrial evapotranspiration: Observation, modeling, climatology, and Climatic variability. Rev. Geophys. 50 (2) (2012).

Fan, J. et al. Comparison of support vector machine and extreme gradient boosting for predicting daily global solar radiation using temperature and precipitation in humid subtropical climates: A case study in China. Energy Convers. Manag. 164, 102–111.

Fan, J. et al. Evaluation of SVM, ELM and four tree-based ensemble models for predicting daily reference evapotranspiration using limited meteorological data in different climates of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 263, 225–241 (2018).

Kahler, D. M. & Brutsaert, W. Complementary relationship between daily evaporation in the environment and pan evaporation. Water Resour. Res. 42 (5) (2006).

Vicente Serrano, S. M. et al. A Comparison of Temporal Variability of Observed and Model-Based Pan Evaporation Over Uruguay (1973–2014) (2018).

Abed, M., Imteaz, M. A., Ahmed, A. N. & Huang, Y. F. Modelling monthly Pan evaporation utilising random forest and deep learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 13132 (2022).

Singh, V. P. & Xu, C. Y. Evaluation and generalization of 13 mass-transfer equations for determining free water evaporation. Hydrol. Process. 11 (3), 311–323 (1997).

Nourani, V., Elkiran, G. & Abdullahi, J. Multi-station artificial intelligence-based ensemble modeling of reference evapotranspiration using Pan evaporation measurements. J. Hydrol. 577, 123958 (2019).

Sarıgöl, M. & Katipoğlu, O. M. Estimation of monthly evaporation values using gradient boosting machines and mode decomposition techniques in the Southeast Anatolia project (GAP) area in Turkey. Acta Geophys. 72 (2), 999–1016 (2024).

Arya Azar, N., Milan, G., Kayhomayoon, Z. & S., & Predicting monthly evaporation from dam reservoirs using LS-SVR and ANFIS optimized by Harris Hawks optimization algorithm. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 1–14 (2021).

Sakib, M., Mustajab, S. & Alam, M. Ensemble deep learning techniques for time series analysis: a comprehensive review, applications, open issues, challenges, and future directions. Cluster Comput. 28 (1), 73 (2025).

Kong, X. et al. Deep learning for time series forecasting: a survey. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 1, 1–34 (2025).

Mahmoud, A. & Mohammed, A. Leveraging hybrid deep learning models for enhanced multivariate time series forecasting. Neural Process. Lett. 56 (5), 223 (2024).

Ullah, K. et al. Short-term load forecasting: A comprehensive review and simulation study with CNN-LSTM hybrids approach. IEEE Access (2024).

Mandic, D. P. & Chambers, J. Recurrent Neural Networks for Prediction: Learning Algorithms, Architectures and Stability (Wiley, 2001).

Schuster, M. & Paliwal, K. K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 45 (11), 2673–2681 (1997).

Malakar, P., Sarkar, S., Mukherjee, A., Bhanja, S. & Sun, A. Y. Use of machine learning and deep learning methods in groundwater. In Global Groundwater 545–557 (Elsevier, 2021).

Khan, J., Lee, E., Balobaid, A. S. & Kim, K. A comprehensive review of conventional, machine leaning, and deep learning models for groundwater level (GWL) forecasting. Appl. Sci. 13 (4), 2743 (2023).

Danandeh Mehr, A., Rikhtehgar Ghiasi, A., Yaseen, Z. M., Sorman, A. U. & Abualigah, L. A novel intelligent deep learning predictive model for meteorological drought forecasting. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 14 (8), 10441–10455 (2023).

Agana, N. A. & Homaifar, A. A deep learning based approach for long-term drought prediction. In SoutheastCon 2017 1–8 (IEEE, 2017).

Majhi, B., Naidu, D., Mishra, A. P. & Satapathy, S. C. Improved prediction of daily Pan evaporation using Deep-LSTM model. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 7823–7838 (2020).

Liu, D., Jiang, W., Mu, L. & Wang, S. Streamflow prediction using deep learning neural network: case study of Yangtze river. IEEE access. 8, 90069–90086 (2020).

Mangukiya, N. K. & Sharma, A. Deep learning-based approach for enhancing streamflow prediction in watersheds with aggregated and intermittent observations. Water Resour. Res. 61 (1), e2024WR037331 (2025).

Mahakur, V., Mahakur, V. K., Samantaray, S. & Ghose, D. K. Prediction of runoff at ungauged areas employing interpolation techniques and deep learning algorithm. HydroResearch 8, 265–275 (2025).

Fu, L., Ding, X. & Ding, Y. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition-based preprocessing method with Multi-LSTM for time series forecasting: a case study for hog prices. Connection Sci. 34 (1), 2177–2200 (2022).

Hao, H., Yu, F. & Li, Q. Soil temperature prediction using convolutional neural network based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Ieee Access. 9, 4084–4096 (2020).

Huang, N. E. et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454 (1971), 903–995 (1998).

Tayyab, M., Ahmad, I., Sun, N., Zhou, J. & Dong, X. Application of integrated artificial neural networks based on decomposition methods to predict streamflow at upper indus Basin, Pakistan. Atmosphere 9 (12), 494 (2018).

He, Y., Mo, J. & Hu, W. A comparative study of EMD, NSP and VMD for signal decomposition. In International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Security (ICSPCS 2024), Vol. 13222, 209–217 (SPIE, 2024).

Chen, Z. et al. An improved method based on EEMD-LSTM to predict missing measured data of structural sensors. Appl. Sci. 12 (18), 9027 (2022).

Huang, Y., Liu, S. & Yang, L. Wind speed forecasting method using EEMD and the combination forecasting method based on GPR and LSTM. Sustainability 10 (10), 3693 (2018).

Wu, Y. X., Wu, Q. B. & Zhu, J. Q. Improved EEMD-based crude oil price forecasting using LSTM networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 516, 114–124 (2019).

Tian, Q. F. et al. An adaptive middle and long-term runoff forecast model using EEMD-ANN hybrid approach. J. Hydrol. 567, 767–780 (2018).

Liao, S. et al. Runoff forecast model based on an EEMD-ANN and meteorological factors using a multicore parallel algorithm. Water Resour. Manage. 37 (4), 1539–1555 (2023).

Liu, X., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Q. Comparison of EEMD-ARIMA, EEMD-BP and EEMD-SVM algorithms for predicting the hourly urban water consumption. J. Hydroinformatics. 24 (3), 535–558 (2022).

Remesan, R. Model data selection and data pre-processing approaches. In Hydrological Data Driven Modelling: A Case Study Approach 41–70 (2015).

Brownlee, J. Long Short-Term Memory Networks with Python: Develop Sequence Prediction Models with Deep Learning (Machine Learning Mastery, 2017).

Roy, D. K. Long short-term memory networks to predict one-step ahead reference evapotranspiration in a subtropical Climatic zone. Environ. Processes. 8, 911–941 (2021).

Panahi, M., Sadhasivam, N., Pourghasemi, H. R., Rezaie, F. & Lee, S. Spatial prediction of groundwater potential mapping based on convolutional neural network (CNN) and support vector regression (SVR). J. Hydrol. 588, 125033 (2020).

Khosravi, K. et al. Convolutional neural network approach for Spatial prediction of flood hazard at National scale of Iran. J. Hydrol. 591, 125552 (2020).

Sameen, M. I., Pradhan, B. & Lee, S. Application of convolutional neural networks featuring bayesian optimization for landslide susceptibility assessment. Catena 186, 104249 (2020).

Wu, Z. & Huang, N. E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: a noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 1 (01), 1–41 (2009).

Rehman, N. & Mandic, D. P. Multivariate empirical mode decomposition. Proc. Royal Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 466 (2117), 1291–1302 (2010).

Arya Azar, N., Kardan, N. & Ghordoyee Milan, S. Developing the artificial neural network-evolutionary algorithms hybrid models (ANN-EA) to predict the daily evaporation from dam reservoirs. Eng. Comput. 39 (2), 1375–1393 (2023).

Singh, A. & Kumar, A. EEMD-CNN based method for compound fault diagnosis of bearing. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Computational Intelligence (CyberneticsCom) 253–258 (IEEE, 2022).

Huang, S. et al. Runoff prediction of irrigated paddy areas in Southern China based on EEMD-LSTM model. Water 15 (9), 1704 (2023).

Amirashayeri, A., Behmanesh, J., Rezaverdinejad, V., Attar, F. & N Evapotranspiration Estimation using hybrid and intelligent methods. Soft. Comput. 27 (14), 9801–9821 (2023).

Sezen, C. Pan evaporation forecasting using empirical and ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) based data-driven models in the euphrates sub-basin, Turkey. Earth Sci. Inf. 16 (4), 3077–3095 (2023).

Deng, H., Chen, W. & Huang, G. Deep insight into daily runoff forecasting based on a CNN-LSTM model. Nat. Hazards. 113 (3), 1675–1696 (2022).

Mohammadi, P. & Asefpour Vakilian, K. Machine learning provides specific detection of salt and drought stresses in cucumber based on MiRNA characteristics. Plant. Methods. 19 (1), 123 (2023).

Javidan, S. M., Ampatzidis, Y., Banakar, A., Asefpour Vakilian, K. & Rahnama, K. An intelligent group learning framework for detecting common tomato diseases using simple and weighted majority voting with deep learning models. AgriEngineering 7 (2), 31 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Middle East in the Contemporary World (MECW) project at the Centre for Advanced Middle Eastern Studies, Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.K.: Methodology, Validation, Software, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft.N.A.A: Formal Analysis, Software, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft.S.Gh.M: Visualization, Writing-review& Editing, Software, Supervision.R.B.: Project Administration, Writing-review& Editing, Supervision.P.K.: Project Administration, Writing-review& Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kayhomayoon, Z., Arya Azar, N., Ghordoyee Milan, S. et al. Improving the performance of daily pan evaporation (Evp) prediction using the ensemble empirical mode decomposition combined with deep learning models. Sci Rep 15, 43178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27255-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27255-8