Abstract

Understanding the hydrodynamic behaviors and fluttering motions of trawl codends is crucial for improving trawl selectivity and controlling fish escape while retaining desired catch. This study investigated factors like mesh size, twine diameter, codend length, knot direction, and twine material on codend fluttering in a flume tank. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) visualized the Strouhal number, fluttering amplitude, and drag force evolution. Backpropagation (BP) neural networks were used to predict oscillatory characteristics under various conditions. Results showed that empty codends had a waist-to-end hanging ratio > 0.8, while codends with catch had ratios < 1.2. T90 and polyethylene meshes maintained mesh openings better than T0 and nylon. The mean drag force coefficient decreased with Reynolds number and then tended to level off slowly. Extreme fluttering amplitudes occurred at Strouhal numbers between 5.41 × 10⁻⁴ and 7.15 × 10⁻⁴. Drag force amplitude increased with mean drag force coefficient for empty codends, but for codends with catch, it increased with smaller mesh sizes, twine diameters, and higher flow velocities. Positional amplitude increased with lower waist-to-end hanging ratio. BP neural network predictions matched experimental results with over 90% accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness in predicting codend oscillations under varying parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

The codend is a traditional trawl component defined as the rear trawl section that retains and accumulates the catch during the trawling. The length varies from a few meters to over 50 m1, and it accounts for approximately 10% of the entire trawl’s hydrodynamic force2. Therefore, optimized the structure geometry and hydrodynamic forces could enhance fish size selectivity and reduce the energy consumption of the codend. To optimize the catch selectivity performance of codends, multiple interacting factors need to be systematically evaluated. Among these, codend geometry (including hanging ratio and circumference), mesh configuration parameters (size, shape, and opening angle), and twine properties have been identified as key determinants3,4,5. Furthermore, the accumulation of catch during fishing operations may alter the codend geometry, reduce escape opportunities for undersized fish, and increase the drag force of codend6,7.

Previous studies have been conducted to examine the effects of solidity ratio, twine area, and knot direction on codend selectivity and hydrodynamic characteristics. Using larger diamond and T90 mesh (this term specifically refers to a type of mesh structure where the knot are rotated by 90 degrees compared to a standard mesh configuration (Fig. 1)) could improve size selectivity in codends, thereby effectively releasing undersized fish8,9. Stewart and Ferro2 investigated the drag of empty codend, the results showed that the codend drag was dependent on the towing speed, the trawl mouth circumference, and the number of meshes around the trawl mouth. In addition, O’Neill et al.6 found that codend drag increased with the increase in the solidity ratio and lateral motion of the codend. However, the fluttering motion, which is also a key factor affecting the codend selectivity and drag force2,10,11,12, must be taken into account.

The trawl codend oscillation caused by turbulence inside and behind the trawl could increase the codend drag and disrupt the swimming track of fish, resulting in difficulty for the caught fish to escape13,14,15. Bouhoubeiny et al.16 found that vortex shedding would be generated, creating strong pressure on the codend as water flow passed through it, which would result in codend oscillation. Conversely, flow field around the codend could be influenced by its oscillation. Specifically, as water flow passed through the codend, the mesh altered the flow direction, creating a pressure gradient at the rear of the codend and inducing oscillation.

The codend motion is related to the codend structure deformation and affects the trawl selectivity by influencing the fish swimming speed and direction1,17,18. Additionally, catch accumulation and codend motion can cause epidermal damage, which affects catch quality and the undersized fish survival rate1. To address the negative impacts on trawl net selectivity, many attempts have been made to improve codend stability. Madsen et al.1 compared the stability of six codend structures and found that the diamond mesh codend was the most stable. Furthermore, based on our previous study of Antarctic krill trawl codend oscillations in full-scale test at sea12, and model tests4,19, the effects of cutting ratio and mesh size on the amplitude and frequency of the codend were studied. It was found that a 4:1 cutting ratio and an enlarged mesh size could effectively improve the codend stability.

However, previous studies have investigated the effects of single or double variables on the oscillating frequency and amplitude of the codend, but, the codend stability in practice depends on multiple interacting parameters. In this study, flume tank experiments and predictive modeling were employed to test and establish the relationship between design parameters (mesh size, twine diameter, codend length, knot direction, and twine material), flow conditions (flow velocity, catch volume) and dynamic responses (geometric deformation, mean drag force, drag oscillation, and positional oscillation). The research firstly synchronously collected data on codend geometric deformation, hydrodynamic forces, and positional oscillation through physical model experiments. Subsequently, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) time-frequency analysis was applied to reveal the evolution patterns of oscillation frequency and amplitude in the experimental codend. Finally, based on codend design parameters, flow conditions, and dynamic responses, the Backpropagation (BP) neural network model was constructed to predict drag characteristics and positional oscillation patterns under all parameter combinations. The analysis would provide essential data that could not only enhance trawl stability, but also provide scientific justification for net design optimization.

Materials and methods

Experimental codend

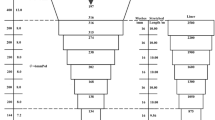

This study used an Antarctic krill trawl codend as the full-scale net, with a total length of 24 m. The codend features a double-layered netting structure, but this experiment focused solely on the outer. The outer netting specifications are: mesh size 144 mm, twine diameter 12 mm. During testing, the inner was removed to conduct experiments using only the outer netting. The model codend based on the modified Tauti’s law was scaled with a large-scale λ of 16 and a small-scale ratio λ’ of 3. Each codend was a four-piece structure, which were detailed in Table 1; Fig. 2. The numbers on the Figure represent the number of meshes on the upper and lower sides of each codend in T-direction and N-direction.

The mesh had two knot directions (T0 and T90), which were shown in Fig. 1.

Experimental equipment and procedures

The experiment was conducted in a flume tank with a capacity of approximately 380 tons of freshwater, as shown in Fig. 3. The main dimensions of the tank are 15.0 m (length) × 3.5 m (width) × 2.3 m (depth), and the flow velocity range is 0–1.5 m/s. A current meter (three-component ECVM ACM3-RS, JFE Advanntech Co., Ltd, Nishinimiya, Japan) was installed approximately 2.0 m upstream of the codend model to detect the flow velocity. The model codend was attached to a circular rigid frame with a diameter of 36 cm (The ring part is made of 304 steel with a diameter of 5 mm, and the handle is made of 304 steel with a diameter of 10 mm.), and the tank provides a camera (manufactured by Dantec Hi-sense, frequency: 59 Hz, resolution: 1920 × 1080 pixels2) to observe and record the codend behavior. To determine the drag force of the codend, the circular rigid frame’s drag was subtracted from the combined structure’s drag. The hydrodynamic force signals of a circular rigid frame and the combined structure were measured with a six-component load cell (TLP-5KS, Tokyo Measuring Instruments Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) with capacity of 5 ± 2% kgf each, the signals were amplified with a dynamic strain amplifier (DPM-6 H), and then sent to an A/D converter and a computer. The data were sampled at 100 Hz.

First of all, the six-component load cell was calibrated and zeroed at the beginning of all experiments. Then the circular rigid frame was connected to a six-component load cell, and positioned perpendicular to the flow direction. The drag force of the frame was then measured at different flow velocities, ranging from 0.3 to 1.1 m/s in 0.1 m/s intervals. Secondly, the measurements of the combined netting-frame were conducted at five different flow velocities (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9 m/s) with a total of 10 × 5 = 50 tests. The six-component instrument was connected to the rigid frame and empty model codend. The flow velocity was adjusted until the codend shape was unfolded and stable. Lastly, the codend with a simulated catch was also measured following same experimental procedure. The catch was simulated using table tennis balls filled with an average of 33.6 g of water, and the diameter of the table tennis balls was 40 mm4,5,19. The total weight of the table tennis balls was 5.04 kg. For each experiment, 80 data points were recorded at a frequency of 4 Hz over a period of 20 s. In addition, the rigid frame had no obvious deformation during all the experiments.

Data extraction of codend motion

During the experiments, a series of images were obtained at 4 Hz over a period of 20 s from the recorded video and were imported into graph digitizing software (GetData 2.20) to extract the coordinates of characteristic points of the model codend. After that, these coordinates, representing the codend behaviors, were subsequently interpolated, thereby allowing the determination of the temporal motions of the different codends. In this study, the markers were placed at codend apex to follow the motions of the whole trawl codend. Thus, only the temporal evolution of the codend apex motions was determined in order to analyze the effect of design factors on the whole codend motions. The longitudinal distance at different points of the codend was taken as the diameter of the cross-section circle. Moreover, the strains in the camera lens, water refraction, and parallax would affect the extraction of these coordinates. A staff was used to mitigate the effect of these strains and to calibrate the measurements (Fig. 4).

Data processing

In this study, the hanging ratio (Et) standardized mesh form was used to reflect mesh opening degree:

where, d is the diameter of the cross-section circle, a is the mesh size, n is the number of mesh at cross-section circle.

The waist-to-end hanging ratio (Rt) means the hanging ratio of the mesh at codend middle part (50% codend length position) to the codend apex part (86% codend length position), which was used to standardize the degree of codend mesh shrinkage at codend middle part.

The drag forces (\(\:{F}_{d}\)) on the trawl codend were found by subtracting the averaged measurements for each flow velocity on the rigid frame from the averaged measurements for each flow velocity on the rigid frame and trawl codend:

The drag coefficient was calculated as follows:

where Cx is the drag coefficient, ρ is the density of water (= 998.2 kg/m³), S is the codend twine areas, and V is the flow velocity.

Reynolds number represents the ratio of inertial and viscous forces:

where d is the twine diameter, ν is the kinematic viscosity (= 0.001005 Pa*s), Re is the Reynolds number.

The FFT methods were implemented to analyze the temporal drag force and codend motion. The FFT was often utilized as a mathematical tool to extract the fluctuating signals in which the features of the signal in time domain, frequency domain, or amplitude can be obtained. The FFT of a discrete time series representing a finite function (t) allow to study the global spectral behavior and enables the extraction of the fluctuating input signals of the random phenomenon in the frequency domain and can be represented by a series, which is defined as:

where (t) is the generic function in the time domain, (f) is the generic function in the Fourier domain, f is the frequency, which can be define as the inverse of the periodicity.

Thus, the Fourier power spectrum that yields the energy distribution of the signal in the frequency domain evaluated over the entire time interval can be defined as:

where Pxx(f) is the Fourier spectrum.

In this study, to analyze the oscillation phenomenon, the spectrum is plotted versus the Strouhal number (\(\:{S}_{t}\)):

where d is the twine diameter, \(\:{u}_{0}\) is the flow velocity.

Data analysis

Backpropagation is an algorithm used to train a neural network in machine learning20. Figure 5 shows the structure of the BP neural network training. Xn is the experimental value, which is input value for the input layer (i = 1, 2, …, n), and n is the number of the input layer; wij is the weight of the j-th hidden layer from the i-th input layer (j = 1, 2, …, p), and p is the number of the hidden layer; wjk is the weight of the k-th output layer from the j-th hidden layer (k = 1, 2, …, m), m is the number of the output layer, and Yk is described as the objective value. For transfer functions from the input to the hidden layer and from the hidden to the output layer, a tangent sigmoid transfer function (tansig) and a linear transfer function (purelin) are chosen and denoted as follows, respectively:

where, aj and bk are threshold values for the hidden and output layers. Ok is the predicted value. The error (ek) different from the expected value Yk is demonstrated as follows:

In each iteration, the weight and threshold values were trained by referring to the gradient descent backpropagation as follows:

where η is the learning rate coefficient (η = 0.1 in this study). The root mean square error (RMSE) less than the order of negative four was applied for convergence. The number of hidden layers was determined using the regression R²-value. In this study, the twine material, mesh size, twine diameter, knot direction, codend length, and flow velocity were the experimental values (Xi) of the six input layers. Additionally, since both twine material and knot direction are categorical variables, “0” and “1” were used to represent “PE” and “PA” materials, respectively, while “0” and “90” were employed to denote “T0” and “T90” knot directions, respectively. The drag force amplitude, and x and z direction positional amplitudes were the objective values (Yk) of the four output layers. The number of units for the hidden layer was chosen as 36 since the excellent prediction accuracy with the regression R²-value was close to 1 in our pretest work. The procedure was conducted using Matlab (The MathWorks Inc.).

Results

The hanging ratio of codend

The hanging ratio of codends assembled on the circular rigid frame was 0.4, and Figs. 6a–j illustrate the mesh hanging ratios at different positions of the codend. It was observed that as the mesh size and twine diameter increased, while codend length decreased, the hanging ratio of the codend increased at the same position. Specifically, the hanging ratio of codend I was the largest, indicating that the codend with T90 mesh exhibited better mesh opening performance. The hanging ratio of codend D was slightly larger than that of codend J, suggesting that the codend with PE mesh had better mesh opening performance compared to the nylon mesh codend. Additionally, the waist-to-end hanging ratio of the codends was greater than 0.8 (Fig. 6k).

When simulated catch was added in the codend, the hanging ratio of the codend waist began to decrease (Fig. 6l), averaging only about 65.2% of that of empty codends. Specifically, the hanging ratio of codend I was the highest. Taking into account the results of the empty codend, it can be considered that the codend using T90 mesh could effectively ensure the maximum opening of the mesh. The waist-to-end hanging ratio of the codend increased as both the mesh size and twine diameter increased. Additionally, the waist-to-end hanging ratio of codend D was 1.72 times that of codend J on average.

The hydrodynamic characteristic of different codends

The mean drag force of 10 empty codends ranged from 5.19 ± 1.64 N to 14.88 ± 3.44 N at flow velocities ranging from 0.5 m/s to 0.9 m/s. The mean drag force increased with larger twine diameter, longer codend length, and higher flow velocities, but decreased with smaller mesh sizes. Notably, the mean drag force of codend I was the highest among all tested codends, reaching up to 22.83 ± 0.18 N at 0.9 m/s (Fig. 7a). For the codend containing catch, the mean drag force ranged from 9.55 ± 3.48 N to 28.85 ± 9.40 N, and it increased as the twine diameter decreased. Furthermore, the mean drag force of codend I remained the largest (Fig. 7b). The drag coefficients of 10 empty codends initially decreased and then tended to level off slowly with increasing Reynolds number (ranging from 660 to 1000). The drag force coefficient of most codends was approximately 0.17, while that of codend I was significantly higher at 0.25. Additionally, the drag force coefficient increased with smaller mesh sizes, larger twine diameters, and longer codend lengths. On average, the drag force coefficient of codend I was the largest (Fig. 7c).

The drag force and positional Oscillation of codends

To facilitate the analysis of codend oscillation characteristics, FFT was applied to analyze the frequency characteristics of codend oscillation signals, and to obtain the correlations among codend drag force, oscillation amplitude, and Strouhal number (Fig. 8). The drag force amplitude of the empty codend was significantly lower compared to the codend with catch (Fig. 8a–j). The positional oscillation of each codend was periodic, with the oscillation amplitude in vertical (z) direction (to the flow direction) being larger than that in horizontal (x) direction (Fig. 8k–t). Additionally, the dominant Strouhal number, corresponding to the primary oscillation frequency, ranged from 5.41 × 10− 4 to 7.15 × 10− 4. In the drag force oscillations of the codend with catch, two distinct amplitude peaks were identified, with the Strouhal number associated with the higher amplitude peak being approximately twice that of the lower amplitude peak (Fig. 8f–j).

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in the amplitudes of drag force and positional oscillations at different flow velocities. The results revealed that the drag force amplitudes of empty codends were below 0.3 N within the velocity range of 0.5 m/s to 0.9 m/s. The amplitudes increased with increasing flow velocity and twine diameter but decreased with decreasing mesh size (Fig. 9a and b). At low flow velocities (< 0.7 m/s), the amplitude of the codend drag force increased with the length of the codend. However, at high flow velocities (> 0.7 m/s), the amplitude decreased with increasing codend length, as shown in Fig. 9c. Furthermore, the drag force amplitude of codend J was significantly higher than that of codends D and I (Fig. 9d and e).

For the codend with catch, the amplitude of the drag force ranged from 0.1 N to 0.5 N. The amplitude increased with the increase of flow velocity and codend length, while the decrease of mesh size and twine diameter (Fig. 9f and g, and 9h). Furthermore, the average drag force amplitudes of codend I and codend J were 17.8% and 34.5% higher than that of codend D, respectively, as shown in Fig. 9i and j.

In x direction, the average positional amplitude of codend B was the largest (0.37 cm), followed by codend C (0.31 cm) and codend A (0.29 cm) (Fig. 9k). The positional amplitude in the x direction of the codend increased with the decreasing twine diameter and codend length (Fig. 9l and m). The positional amplitudes of codend I and codend J were larger (178.9%, 191.2%, respectively) than that of codend D (0.13 cm) (Fig. 9n and o). In z direction, the average amplitude of codend B was the largest (2.98 cm), followed by codend A (2.13 cm), and the average amplitude of codend C was smallest (1.15 cm) (Fig. 9p). Moreover, in z direction, the positional amplitude increased as the twine diameter decreased (Fig. 9q). However, there was no significant relationship between codend length and positional amplitude in z direction, which was different from the x direction (Fig. 9r). Additionally, the positional amplitudes of codend I and codend D were basically the same at the same flow velocity (Fig. 9s), while the average positional amplitude of codend J (3.02 cm) was 2.1 times as much as that of codend D (1.41 cm) (Fig. 9t).

Analysis of the codend Oscillation based on BP neural network training

BP neural network training was used to predict the experimental parameters (twine material, mesh size, twine diameter, knot direction, codend length, and flow velocity) on the drag force and positional amplitudes of codend, and the results were shown in Fig. 10. Based on BP neural network training, the test errors for the drag force amplitude and positional amplitude of the codend were 5.66%, 3.92%, 8.45%, and 10.02%, respectively, corresponding to the drag force amplitude of empty codend, drag force amplitude of codend with catch, positional amplitude in x direction, and positional amplitude in z direction.

Taking the codend I as an example, the estimated oscillation characteristics showed good agreement with the model experiments, with validation errors of 18.98% for the drag force amplitude of the empty codend, 3.33% for the drag force amplitude of the codend with catch, 6.26% for the positional amplitude in x direction, and 7.15% for the positional amplitude in z direction, as shown in Fig. 11. This means that the model based on BP neural network training can be used as a prediction method of codend amplitude.

Discussion

Selection rationale for catch substitutes in codend model experiments

In actual fishing operations, the accumulation of catch in the codend produced debris and settlement, which affected experimental results and equipment. Therefore, catch substitutes were used in model experiments. Madsen et al.1 used multiple small water-filled bags to evaluate the effects of mesh type on the hydrodynamic characteristics and oscillations of the codend. Liu et al.4,19 used water-filled table tennis balls to assess the effects of codend cutting ratio and mesh size on codend oscillation characteristics. However, this method had limitations. Firstly, in this study, although water-filled table tennis balls offered good operability and repeatability, their surface properties and buoyancy parameters differed significantly from those of real catch. The smooth surface of the water-filled table tennis balls could not simulate the hydrodynamic characteristics of fish mucus layers. Their uniform density distribution also struggled to replicate the non-uniform mass distribution of actual catch. Secondly, these limitations directly affected the accuracy and generalizability of neural network predictions. Systematic deviations between training data and actual scenarios could lead to errors in the model in the following aspects: first, predictions of codend resistance might deviate from actual values; second, predictions of codend swing frequency might not accurately reflect the dynamic response of real catch; third, model performance might decline when extended to different fish species. Finally, when applying these research findings to future fishing gear design, it was necessary to fully consider the experimental constraints. We recommended introducing appropriate correction factors in practical applications. Sufficient sea trials were also necessary during the prototype testing phase. Meanwhile, future studies should establish more comprehensive fish catch databases to gradually reduce reliance on substitutes.

It should be noted that the use of water-filled table tennis balls in this study was a necessary choice based on experimental feasibility. Their advantage lay in providing stable experimental conditions and ensuring consistency and comparability of measurement data. Although the aforementioned limitations existed, the analytical framework and methodology established in this study remained valuable for future research.

The effect of drag force on hanging ratio of codend

The geometry configuration and mesh opening of the codend were primarily influenced by hydrodynamic drag force and catch loading4. During trawling operations, the shape of the flexible codend and external forces interacted dynamically. External forces deformed the codend shape, which in turn altered force distribution. This formed a fluid-structure coupling process. Notably, mesh opening affected not only the hydrodynamic performance of the codend but also enabled undersized fish to escape. This improved size selectivity, which was crucial for sustainable fishery resource utilization.

In the empty codend condition, the waist-to-end hanging ratio of most codends was greater than 1 (the cross-sectional area at the waist was larger than that at the posterior). This might indicate that the external force distribution on the codend was relatively balanced. Under water flow, the meshes were able to fully expand. However, the codend H exhibited different mechanical characteristics. Its waist-to-end hanging ratio was approximately 0.8 (the cross-sectional area at the posterior was larger than that at the waist). This suggested a force concentration phenomenon. We speculated that there might be three possible reasons for this. Firstly, the codend H had a larger twine area and longer codend length. Secondly, the netting near the codend posterior was affected by the shielding effect from forward netting, limiting its expansion. Thirdly, external hydrodynamic forces consequently concentrated at the posterior of the codend. This special force distribution resulted in hydrodynamic force concentration occurring at the posterior, and the hydrodynamic forces created inward transverse pressure on the waist, leading to its contraction. This unique hydrodynamic distribution pattern explained why the waist-to-end hanging ratio of codend H was below 1.

When codend was loaded with catch, the waist-to-end hanging ratio was typically less than 1, which could indicate that the codend waist contracted into a narrow channel while the posterior cross-sectional area increased relatively. This phenomenon reflected fundamentally the significant influence of catch accumulation on the hydrodynamic characteristics around the codend. Bouhoubeiny et al.16 analyzed this phenomenon using PIV technology, and revealed that catch blocked the meshes at the codend posterior. The blockage obstructed direct water passage through the meshes at codend posterior, inducing reverse flow that exited through the meshes at waist. This flow redirection created a distinct impact load concentration zone at the codend posterior, causing an aggregated external force distribution pattern19. Notably, a special phenomenon was observed during experiments with codend G, where the waist-to-end ratio reached 1.2 at 0.5 m/s flow velocity but decreased to 0.8 when the velocity increased to 0.8 m/s. This transitional pattern originated likely from the shorter length of codend G. Under lower flow velocities, the inward transverse pressure generated by hydrodynamic force at the posterior of codend was insufficient to cause significant waist constriction. However, as flow velocity increased, the enhanced hydrodynamic force strengthened substantially the waist contraction force, eventually forming the typical narrow-waist structure and demonstrating similar hydrodynamic response characteristics as other codends.

The codend I showed the highest overall hanging ratio compared to other codends. This suggests that using T90 mesh may be an effective method to improve size selectivity of codends and facilitate the escape of undersized fish. Herrmann et al.9 and Priour21 demonstrated that meshes stretched in the T0 direction tend to form closed rhomboid shapes. In contrast, the T90 meshes maintain open hexagonal shapes due to support from knot structure (Fig. 1). During fishing operations with simulated catch loads, transverse forces cause the codend waist to contract into a narrow channel. However, the T90 meshes can maintain a relatively high waist hanging ratio ranging from 0.7 to 0.9 because of their knot orientation. This preserves continuous escape opportunities for undersized fish. Numerical simulations by Priour21 confirmed that T90 codends exhibit less waist contraction and significantly shorter narrow sections than T0 codends under identical conditions. Furthermore, the study found that adjusting mesh size, twine diameter, or changing twine material had no significant effect on improving the waist hanging ratio.

The effect of hanging ratio on Oscillation of codend

There was a noticeable oscillation of the codend when the simulated catch was located (Figs, 8k–t), which had also been confirmed by previous studies16,19,22. However, the amplitude of codend increased with the decrease of twine diameter. The reason might be that the catch altered the codend shape, with the front mesh closed and the rear contour bulged23. The catch blocked direct water flow through the posterior meshes of the codend, diverting and forcing it to reverse through the front meshes. Thereby generating a series of alternating up-and-down vortices16,24,25.

Notably, the waist-to-end hanging ratio of codend F (0.52) was significantly lower than that of codend E (0.73) and codend D (0.74), with reductions of 29.46% and 29.88%, respectively. The narrow waist of codend F could not provide sufficient lateral binding force to counteract the hydrodynamic forces, resulting in higher oscillation amplitudes. Additionally, codends G, E, and H demonstrated that lateral amplitude did not increase proportionally with codend length. The results might indicate the amplitude of the codend was correlated with the waist-to-end hanging ratio. Specifically, a higher waist-to-end hanging ratio enhanced lateral binding force, thereby reducing oscillation amplitude of the codend.

The knot direction and twine material could significantly affect the oscillation of the codend. The drag force amplitude of empty codend I (with T90 mesh) was smaller than that of codend D (with T0 mesh). That might be due to the T90 mesh could maintain the mesh opening and keep large filtration of codend. Even when the codend was loaded with catch, codend I maintained a high hanging ratio (0.70–0.90), effectively suppressing oscillations through enhanced lateral binding. Furthermore, nylon exhibited greater flexibility compared to PE, and the waist-to-end ratio of codend J was relatively small, resulted in insufficient lateral binding force and larger oscillation amplitudes than codend D. It was recommended to select stiffer materials to improve codend stability.

The drag oscillation exhibited two dominant amplitudes (Figs. 8f–j). The larger Strouhal number was twice the smaller one, indicating dual primary frequencies, with the higher frequency doubing the lower. Liu et al.19 reported that third-order Fourier transforms achieved 86.7% accuracy in fitting drag oscillations, whereas second-order sufficed for positional oscillations. This complexity might arise from alternating strong vortices (large amplitude) and weak vortices (small amplitude), both contributing to positional oscillations. However, due to observational limitations (side-view recording), positional oscillations displayed only one dominant amplitude.

Liu et al.12 previously analyzed the oscillation characteristics of the full-scale codend used in this study during actual fishing operations. A comparison between the full-scale trawl codend and the model codend revealed both similarities and differences in their oscillation characteristics. The full-scale trawl tests showed that the codend oscillation period ranged from 50 to 90 s, with an amplitude reaching up to 4 m during net shooting and hauling stages, while it stabilized at 0.2–0.6 m during the towing stage. In contrast, the model codend also exhibited significant oscillations, but its amplitude variations were more sensitive to structural parameters such as twine diameter and hanging ratio. Notably, external factors like warp tension dominated the amplitude changes in the full-scale trawl codend, whereas the model codend highlighted the critical role of the waist-to-end hanging ratio, an internal structural parameter in governing oscillations. Additionally, the model codend exhibited two dominant frequency oscillations, a feature not observed in full-scale tests due to environmental complexity. These differences indicated that full-scale trawl codend better reflect macro-scale hydrodynamic behavior during actual operations, while model trawls are more suitable for investigating micro-scale mechanisms related to gear structural parameters. The two approaches complement each other and collectively enhance the understanding of codend oscillation dynamics.

Prediction of codend Oscillation characteristics based on BP neural network training

This study employed a BP neural network to model the oscillation characteristics of trawl codends, demonstrating its capability to predict variations in drag force and displacement amplitude under different parameter combinations (mesh size, twine diameter, codend length, knot direction, twine material, and flow velocity). The training results showed prediction errors of 5.66% (empty codend drag amplitude) and 3.92% (codend with catch drag amplitude), while the errors for x and z-direction displacement amplitudes were 8.45% and 10.02%, respectively, with an overall fitting accuracy exceeding 90%. This might indicate the model’s high reliability. Notably, error distribution analysis revealed that predictions for empty codends exhibited higher errors (18.98%) compared to loaded catches (3.33%), possibly due to unstable flow separation points caused by excessive mesh deformation in unloaded conditions.

The model further elucidated the influence of various parameters on hydrodynamic performance: twine diameter contributed maximal impact to drag variations (42.3%), while knot direction had minimal impact on vertical amplitude (6.8%). This finding provided clear guidance for optimizing fishing gear design. Compared to conventional CFD simulations, this approach significantly improved computational efficiency, reducing analysis time from hours to minutes while maintaining 85% accuracy, making it highly valuable for rapid decision-making in fisheries engineering.

The accuracy of the BP neural network training could be improved by using a large volume of training data26. Thus, future studies could explore transfer learning techniques to enhance prediction accuracy under limited experimental data by incorporating finite element method (FEM) simulations. Additionally, as datasets expand, graph convolutional networks (GCNs) might prove more effective in modeling dynamic topological changed in netting structures, offering new possibilities for next-generation smart fishing gear design.

Conclusion

In this study, the hydrodynamic forces and fluttering motions of codends in midwater fisheries were systematically investigated, focusing on the effects of mesh size, twine diameter, knot direction, twine material, and codend length. Through a series of experiments involving ten codend models in a flume tank, key hydrodynamic parameters such as the mesh hanging ratio, drag force, and drag force coefficient were measured under both empty and catch conditions. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis was employed to visualize the drag force and positional oscillation of the codend, while BP neural network training was utilized to model the fluttering motion and predict oscillatory characteristics under various parameter combinations.

For the empty codend, the drag force coefficient was found to decrease with increasing mesh size and decreasing twine diameter. Notably, the T90 mesh codend exhibited the highest drag force coefficient and waist-to-end hanging ratio among all experimental models, suggesting its potential to enhance trawl selectivity. In the case of codends with catch, FFT analysis revealed a synchronization between drag force and positional oscillation. Both drag force and positional amplitude increased as the waist-to-end hanging ratio decreased and flow velocity increased. Furthermore, the use of T90 and PE mesh was shown to improve the stability of the codend.

The BP neural network training demonstrated high accuracy, with a fitting accuracy exceeding 90% based on the six dependent variables established in the experiments. This suggests the BP neural network training is a reliable method for predicting codend drag force and positional amplitude across all parameter combinations. Overall, the findings provide valuable insights into optimizing codend design and operation in midwater fisheries, contributing to improved selectivity and stability in trawl systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Madsen, N., Hansen, K. & Madsen, N. A. H. Behavior of different trawl codend concepts. Ocean. Eng. 108, 571–577 (2015).

Stewart, P. A. M. & Ferro, R. S. T. Four experiments investigating codend drag. Fish. Res. 5, 349–358 (1987).

Priour, D. Numerical optimization of trawls design to improve their energy efficiency. Fish. Res. 98, 40–50 (2009).

Liu, W. et al. The profile and fluttering characteristics of a codend with different mesh sizes and catch by fast fourier transform and Morlet wavelet methods. Fish. Res. 264, 106714 (2023).

Nyatchouba, N. B. T. et al. Experimental analysis of the influence of gear design and catch weight on the fluid-structure interaction of a flexible codend structure used in trawl fisheries. Appl. Sci. 13, 2505 (2023).

O’Neill, F. G., Knudsen, L. H., Wileman, D. A. & McKay, S. J. Cod-end drag as a function of catch size and towing speed. Fish. Res. 72, 163–171 (2005).

Wan, R. et al. Hydrodynamic performance of a newly-designed Antarctic Krill trawl using numerical simulation and physical modeling methods. Ocean. Eng. 179, 173–179 (2019).

Grimaldo, E., Sistiaga, M. & Larsen, R. B. Evaluation of codends with sorting grids, exit windows, and diamond meshes: size selection and fish behavior. Fish. Res. 91, 271–280 (2007).

Herrmann, B., Priour, D. & Krag, L. A. Simulation-based study of the combined effect on cod-end size selection of turning meshes by 90° and reducing the number of meshes in the circumference for round fish. Fish. Res. 84, 222–232 (2007).

Kim, Y. H. Analysis of turbulence and Tilt by in-situ measurements inside the codend of a shrimp beam trawl. Ocean. Eng. 53, 6–15 (2012).

Kim, Y. H. Fluttering characteristics of the ropes and Nets as an active stimulating device inside the Cod end of a trawl net. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 16, 101–108 (2013).

Liu, W. et al. Revealing the phenomenon of fluttering motions of a mid-water trawl codend through sea trials: A case study of Antarctic Krill trawl codend. J. Ocean. U China. 22, 555–564 (2023).

Bouhoubeiny, E., Druault, P. & Germain, G. Phase-averaged mean properties of turbulent flow developing around a fluttering sheet of net. Ocean. Eng. 82, 160–168 (2014).

Lomeli, M. J. M. & Wakefield, W. W. The effect of artificial illumination on Chinook salmon behavior and their escapement out of a midwater trawl bycatch reduction device. Fish. Res. 218, 112–119 (2019).

Nyatchouba, N. B. T. et al. Comparison between physical model testing and numerical simulation using two-way fluid-structure interaction approach of new trawl design for coastal bottom trawl net. Ocean. Eng. 233, 109112 (2021).

Bouhoubeiny, E., Germain, G. & Druault, P. Time-resolved PIV investigations of the flow field around rigid cod-end net structure. Fish. Res. 108, 344–355 (2011).

Priour, D. & Prada, A. An experimental/numerical study of the catch weight influence on trawl behavior. Ocean. Eng. 94, 94–102 (2015).

Nyatchouba, N. B. T., Tang, H., Achille, N. P., Xu, L. & Hu, F. Unsteady turbulent flow developing inside and around different parts of fluttering trawl net in flume tank. J. Fluid Struct. 108, 103451 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Effect of cutting ratio and catch on drag characteristics and fluttering motions of mid-water trawl codend. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 256 (2021).

Dong, S. C., You, X. X. & Hu, F. X. Effects of design factors on drag forces and deformations on marine aquaculture cages: a parametric study based on numerical simulations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8, 125 (2020).

Priour, D. Modelling axisymmetric codends made of hexagonal mesh types. Ocean. Eng. 92, 1–11 (2014).

Pichot, G., Germain, G. & Priour, D. On the experimental study of the flow around a fishing net. Eur. J. Mech. B-Fluid. 28, 103–116 (2009).

O’Neill, F. G. Differential equations governing the geometry of a diamond mesh cod-end of a trawl net. J. Appl. Mech. 64, 7–14 (1997).

Jones, E. G., Summerbell, K. & O’Neill, F. The influence of towing speed and fish density on the behaviour of Haddock in a trawl cod-end. Fish. Res. 94, 166–174 (2008).

Nyatchouba, N. B. T. et al. Identifying the turbulent flow developing inside and around the bottom trawl by electromagnetic current velocity meter approach in the flume tank. J. Hydrodyn. 33, 636–656 (2021).

You, X., Hu, F., Dong, S., Takahashi, Y. & Shiode, D. Shape optimization approach for cambered otter board using neural network and multi-objective genetic algorithm. Appl. Ocean. Res. 100, 102148 (2020).

Funding

This study was supported by the Marine S&T Fund of Shandong Province for Qingdao Marine Science and Technology Center (No.2022QNLM030001-4), Taishan Industrial Innovation Leading Talent of Shandong Province, the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, ECSFR, CAFS (NO. 2022YC02), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD2401203), Special Fund for Science and Technology Development in Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province (2022A01037), the Shanghai Sailing Program (23YF1459700; 24YF2759300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WL investigation, methodology, sofware, writing original draft, data curation, conceptualization, validation. MM investigation, conceptualization, funding acquisition, review & editing the original draft, data curation, validation. NBTN conceptualization, data curation. ZW conceptualization, validation. YL methodology, software. XZ funding acquisition, review & editing the original draft, data curation, supervision. LW investigation, conceptualization, validation, data curation, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Min, M., Nyatchouba, B.N. et al. Estimating dynamic behavior of trawl codend based on machine learning models. Sci Rep 15, 43353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27276-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27276-3