Abstract

Metal-free, environmentally friendly photocatalysts offer a valuable alternative to conventional metal-based semiconductors. In this study, we developed a photocatalyst based on a covalent organic triazine polymer (COTP) using an efficient synthetic route. Comprehensive characterization was conducted to assess the physical (TEM, FESEM-EDS, and elemental mapping), chemical (FTIR and XRD), and optical (UV-Vis-DRS) properties of the synthesized photocatalyst and to evaluate its photocatalytic performance for the selective oxidation of tamoxifen (TMX) when exposed to visible light. The COTP exhibited remarkable photocatalytic efficiency, achieving a rate constant of 0.0599 min− 1 in degrading TMX. Optimal performance was obtained under the following conditions: a photocatalyst dose of 40 mg/L, a pH of 7, an initial TMX concentration of 10 mg/L, 60 min of irradiation. Furthermore, radical trapping experiments revealed that electrons (e−), superoxide radicals (O•−), and holes (h•) play crucial roles in the photodegradation process of TMX. Additionally, the COTP exhibited excellent stability, maintaining over 83% TMX degradation efficiency even after five consecutive cycles. These results highlight the significant potential of triazine-based polymers for the treatment of drug-contaminated wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic systems poses considerable adverse effects, including mutagenesis, fetotoxicity, carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, the emergence of drug resistance, and allergic reactions1,2,3. These effects can significantly impact human health as well as wildlife and other aquatic organisms4. Sources of such pollutants are diverse, encompassing discharges from healthcare facilities, residential wastewater, livestock farming, aquaculture, and large-scale agricultural operations5,6,7.

Tamoxifen (TMX) is among the pharmaceutical contaminants identified in various water sources worldwide, including drinking water, surface water, and groundwater, at concentrations in the nanograms per liter (ng/L) range8,9,10. This widespread occurrence can be largely attributed to the increasing use of chemotherapy drugs in cancer treatments11,12.

TMX, a mutagenic and teratogenic anticancer agent, is notably resistant to biological degradation13. This persistence raises serious concerns about occupational exposure and potential ecotoxicological risks, necessitating a closer examination of TMX’s impact on ecological systems and human health14. TMX is a selective estrogen receptor modulator commonly utilized in the treatment of breast cancer and, to a lesser degree, in disease prevention10,15. TMX undergoes extensive metabolism, producing several active metabolites, including N-desmethyltamoxifen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, tamoxifen-N-oxide, hydroxytamoxifen, and N-didesmethyltamoxifen16. TMX exhibits very low levels of oral bioavailability; therefore, following patient treatment, it may be expelled into the environment, both in its native form and as its metabolic byproducts8,17. Once introduced into aquatic environments, TMX can adversely affect developing eukaryotic organisms. Numerous studies have investigated various methods for the removal of TMX from aquatic environments, including membrane filtration, advanced oxidation processes, adsorption techniques, and coagulation-flocculation methods. Among these, photocatalytic processes hold particular promise as effective approaches for the degradation and removal of anticancer drugs such as TMX18,19.

Porous organic polymers (POPs) have emerged as highly promising candidates for organic semiconductor photocatalysts, particularly owing to their low cost and ease of processing20. They are especially effective in the degradation of pollutants21. Covalent triazine-based frameworks (CTFs), first developed in 2008, are among the most intriguing types of porous organic polymers (POPs) currently under investigation22,23. These materials are composed of aromatic 1,3,5-triazine units and primarily consist of readily available elements such as carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen24. Characterized by their high nitrogen content, CTFs exhibit highly reactive triazine functionalities, broad light absorption, and exceptional thermal and chemical stability under visible-light irradiation25,26. CTFs have unique features in terms of surface area, pore size, nitrogen content, and optical band gap. Porous triazine-based polymers constitute a unique class of POPs defined by their exceptionally stable triazine linkages27. Furthermore, using metal-free catalysts benefits environmental sustainability by eliminating the risk of metal leaching, thereby enhancing the ecological viability of catalytic processes28,29,30.

Building on the insights provided, we successfully synthesized a covalent organic triazine polymer by linking 3,4,9,10-perylene tetracarboxylic dianhydride (PTCDA) as the core structural unit with tris(4-aminophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (TAT), a triazine-based amine. This approach creates a network of repeating molecular units, interconnected by robust covalent bonds, thereby enhancing the stability and applicability of the resulting polymer. The synthesized polymer functions as a metal-free polymeric semiconductor for the degradation of TMX under visible-light irradiation. The resulting photocatalyst demonstrated improved photocatalytic efficiency for degrading contaminants of emerging concern in aqueous environments.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Cyanuric chloride (C3Cl3N3), p-nitrophenol (C6H5NO3), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), acetone (CH3)2CO), methanol (CH3OH), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), ethanol (C2H6O), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), 3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (C24H8O6), anhydrous zinc acetate (C4H6O4Zn), imidazole (C3H4N2), and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were obtained from Merck, Germany. A stock solution of tamoxifen at a concentration of 1000 mg/L was prepared using deionized water. All chemicals used were of analytical quality and were used as received, without further purification.

Synthesis of covalent organic triazine polymer (COTP)

The synthesis of COTP was conducted in two distinct stages. Initially, cyanuric chloride (1.5 g, 8.2 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of acetone and stirred to ensure complete dissolution. This cyanuric chloride solution was then gradually added to a separate solution containing p-nitrophenol (3.0 g, 25.2 mmol) and sodium hydroxide (1.0 g, 25.2 mmol), which had been prepared by dissolving the p-nitrophenol and NaOH in a mixture of 100 mL of water and 20 mL of acetone. The combined reaction mixture was refluxed at 60 °C for 2 h to ensure complete reaction. Following reflux, the product was isolated by filtration, then thoroughly washed several times with deionized water and methanol, to remove any unreacted reagents and by-products. The resulting compound was then dried under vacuum, yielding tris(4-aminophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (TAT) as a white crystalline solid.

Subsequently, TAT (1.78 g, 3.7 mmol), ammonium chloride (3 g, 55 mmol), ethanol (60 mL), and deionized water (20 mL) were combined in a 250 mL flask to initiate the next reaction. The mixture was stirred and heated to 80 °C for 2 h to facilitate the subsequent reactions. After refluxing, 3.0 g (55 mmol) of reduced iron powder was introduced to the mixture and then the mixture was filtered to separate the solid components from the liquid phase. The resulting filter cake, which contained unreacted materials and by-products, was washed twice with 10 mL of ethanol.

Then, sodium bicarbonate was added to the combined filtrates to adjust the pH to 9. Upon reaching the targeted pH level, pale yellow TAT began to precipitate from the solution. In the second stage of the synthesis, a 100 mL flask was prepared by combining 0.804 g (2.0 mmol) of TAT, 1.176 g (3.0 mmol) of PTCDA, 0.55 g (3.0 mmol) of anhydrous zinc acetate, and 8.0 g of imidazole. The mixture was then heated to 200 °C for 12 h. Once cooled, the mixture was dispersed in a 200 mL solution of hydrochloric acid (1 M) and stirred for 8 h.

The resulting dark red solution was collected by vacuum filtration using a membrane filter with a pore size of 0.45 μm. To remove residual by-products, the collected solid was washed thoroughly with deionized water and then oven-dried for 24 h24 (Fig. 1).

Photocatalytic tests

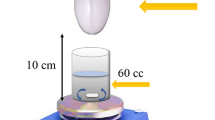

The photocatalytic performance of the synthesized covalent organic triazine polymer was assessed for its efficacy in degrading TMX in an aqueous solution. A 50 W LED-COB lamp served as the light source for photocatalytic reactions.

Following standard photocatalytic protocols, 100 mL of a TMX solution at a concentration of 10 mg/L was prepared and mixed with 40 mg/L of the synthesized COTP in a 100 mL Pyrex reactor.

To ensure optimal conditions for the adsorption process, the mixture was agitated in the dark for 30 min. The reactor was then aerated to purge the suspension and maintained at a constant temperature of 25 °C using a water-cooling system.

Once the system was adequately prepared, the lamp was switched on to initiate the photocatalytic process (Fig. 2). At predetermined intervals ranging from 0 to 2 h, 3.5 mL samples were withdrawn from the reactor. Each sample was then filtered using cellulose filters (Whatman, 0.22 μm) to remove any solid particles. The filtered samples were subjected to UV-visible spectrophotometric analysis using a Lambda 45 spectrophotometer from Perkin-Elmer.

To evaluate the photocatalytic performance quantitatively, the removal efficiency was calculated using Eq. (1), which defines the removal efficiency parameter, qe. This parameter is crucial for understanding the removal capacity of the photocatalyst and its effectiveness in degrading TMX under the given experimental conditions.

where C0 and Ce represent the initial and equilibrium TMX concentrations in mg/L, respectively, V denotes the volume of the standard TMX solution in L, and W indicates the mass of COTP used in each test in grams.

Results and discussion

Characterization of COTP

The FT-IR spectra of COTP, TAT, and PTCDA are illustrated in Fig. 3. The spectrum of PTCDA displays characteristic symmetric and asymmetric stretching bands of the anhydride C = O groups at wavelengths of 1770 cm− 1 and 1736 cm− 1, respectively. In contrast, the FT-IR spectrum of TAT reveals stretching vibrations of NH2 groups at 3367 cm− 1. Additionally, significant C = N stretching vibrations and the breathing modes of the triazine cores appear at 1586 cm− 1 and 832 cm− 1, respectively.

After polymerization, a prominent absorption peak emerges at 1662 cm− 1, indicating the formation of imide groups. The broadening of peaks in the fingerprint region further reflects the development of the polymeric architecture of COTF-P. Notably, the 1770 cm− 1 and 1736 cm− 1 peaks characteristic of the PTCDA spectrum disappear, confirming structural transformation upon polymerization.

The crystal structure of COTP was evaluated using X-ray diffraction (XRD). As depicted in Fig. 4a, several prominent peaks are evident at 2θ = 8.0°, 10.1°, and 15.9°; while, the presence of a peak at 2θ = 26.1° indicates partial crystallinity of the polymer. Based on the data presented in Fig. 4b, nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis using the BET method indicated that COTP possesses a specific surface area of 3.78 m²/g and a total pore volume of 0.011 cm³/g. In terms of its behavior, the COTP specimen exhibits features characteristic of a typical type IV isotherm, with an H3 hysteresis loop.

To examine the morphology of COTP in detail, TEM and FESEM images were captured at various magnifications. The TEM images reveal that COTP has a nanosheet-like arrangement, showing a stacked, layered structure formed by overlapping two-dimensional sheets (Fig. 5a, b, and c). As shown in Fig. 5d, e, and f, the FESEM images confirm this nanosheet-like structure. Furthermore, EDX and FESEM-EDX elemental mapping analysis of COTP demonstrate the high purity of the synthesized material and confirm the presence of the expected elements (C, O, and N) (Figs. 5g–I, 6 and 7).

The optical characteristics were analyzed using DRS-UV-visible technique, with the absorption spectra shown in Fig. 6a. The COTP sample exhibited strong absorption in two regions, with a significant drop occurring around 410 nm and 923 nm. The energy gap values, calculated using the Tauc plot method (Fig. 6b), were estimated at 1.16 eV and 2.4 eV. For the photocatalytic studies, the energy gap of 2.4 eV was considered because the recombination rate is significantly higher.

Photoactivity of COTP for TMX degradation

To assess the effectiveness of COTP for degrading pollutants, TMX was used as a model compound. Before light exposure, the samples were kept in the dark for 30 min to reach a stable adsorption-desorption state. COTP showed only slight TMX adsorption, approximately 10%. TMX also exhibited degradation under light alone, resulting in only a 21.5% reduction observed in the absence of a catalyst. As shown in Fig. 7, the photocatalytic activity of COTP resulted in approximately 97.3% TMX removal within 60 min.

To gain deeper insight into the photocatalytic processes involved in TMX degradation, we employed a pseudo-first-order kinetic model. This approach allowed us to compare the TMX removal efficiencies of various samples under photocatalytic conditions.

where kt is the rate constant based on the Langmuir-Hinshelwood model, illustrating the relationships between relevant factors. The variable t represents the duration of light exposure, while, Ct and Ce (mg/L) denote the TMX concentrations at the start and at time t ranging from − 30 to 120 min. Based on Fig. 8a and b, the calculated rate value ‘k’ for the photocatalytic degradation of TMX is 0.0599 min-1. The results indicate that the synthesized COTP achieved a high degradation efficiency of 99.2% for tamoxifen, outperforming the photocatalytic systems reported in other studies (see Table 1).

To understand the photocatalytic mechanism of COTP, we conducted chemical scavenger experiments to assess the roles of different reactive oxygen species. We introduced BQ, AgNO3, TBA, and EDTA-2Na to quench superoxide radicals (\(\:{\text{O}}_{2}^{{\cdot\:}-})\), excited electrons (e-), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and photogenerated holes (h•), respectively. The results shown in Fig. 8c and d reveal that the degradation process was significantly affected by the presence of BQ, with the TMX rate constant k dropping from 0.0599 min-1 to 0.0034 min-1, highlighting the critical role of \(\:{\text{O}}_{2}^{{\cdot\:}-}\). Similarly, EDTA-2Na reduced the rate constant to 0.0048 min-1 and degradation efficiency to 32%, suggesting that photogenerated holes play a crucial role. AgNO3 also exhibited a substantial inhibitory effect on TMX degradation. In contrast, TBA caused only an 18% decrease in TMX removal efficiency (Fig. 8c and d), with kOBS decreasing from 0.0599 min-1 to 0.03 min-1. This indicates that TMX photodegradation continues with minimal reduction in OH• activity, implying that hydroxyl radicals contribute less to TMX degradation compared to other reactive species generated by COTP.

Analying the degradation of TMX using COTP under visible light reveals its effectiveness, despite a relatively narrow band gap of 2.4 eV, which can be attributed to the presence of oxygen vacancies. These vacancies facilitate the rapid reduction and oxidation of TMX by providing excess electrons and holes within COTP during photocatalytic degradation reactions.

Furthermore, photogenerated electrons within the COTP structure may contribute to the conversion of molecular oxygen (O2) into superoxide radical anions (\(\:{\text{O}}_{2}^{{\cdot\:}-}\)). Subsequently, these activated superoxide species participate in TMX degradation, either directly or through the generation of secondary reactive species within the reaction environment (Eq. 3 to 8).

According to Athar et al. (2024) and Zandipak et al. (2024), a plausible photocatalytic mechanism is proposed. As shown in Fig. 9, the bandgap (Eg) of COTP was determined to be 2.4 eV, with valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) potentials at + 1.49 V and − 0.61 V, respectively. Under visible light irradiation, the COTP photocatalyst absorbs energy, leading to electron excitation and the generation of electron-hole pairs. Owing to the high charge carrier mobility facilitated by its sp²-hybridized carbon framework with C = C bonds, electrons (e−) are efficiently promoted from the VB to the CB. This process leaves behind a significant number of positively charged holes (h+) in the VB, increasing the exposure of photogenerated holes on the catalyst surface24,31. Subseuently, these holes effectively oxidize TMX molecules.

Effect of primary pH

The photocatalytic efficiency of TMX degradation is significantly influenced by the initial pH level, due to its effects on both the surface charge of the COTP and the ionization state of TMX. Specifically, in the photodegradation of TMX, an increase in pH from 3.0 to 7.0 led to a significant enhancement in performance, with removal efficiency rising from 35% to 97%, and the rate constant increasing significantly from 0.006 min− 1 to 0.059 min− 1 (Fig. 10a, b). However, beyond pH 7.0, the photocatalytic performance declined. Thus, the optimal pH for TMX degradation was determined to be 7.0, where the reaction rate constant (k) reached its maximum value.

The acid-base properties of TMX, characterized by a pKa of 8.7, determine its ionic state at different pH levels. At pH values near 8.7, the zwitterionic form prevails, while anionic and cationic species dominate at pH values below and above this point, respectively. Concurrently, the surface charge of COTP depends on the solution pH relative to its pHpzc, which was experimentally determined to be 5. At pH values above the pHpzc, the COTP surface acquires a negative charge due to the preferential adsorption of OH− ions. Conversely, below pH 5, the surface becomes positively charged because of the presence of H ions. At pH ≤ pHpzc (≤ 5), the COTP surface is predominantly positively charged. In the presence of TMX, this results in the formation of positively charged TMX+ species.

Consequently, the electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged COTP surface and TMX+ molecules reduces their interaction, thereby impeding the oxidation of the formed TMX+. However, as the pH is gradually increased, TMX degradation efficiency rises, reaching a peak removal rate of 97% at pH 7. This optimal degradation efficiency is attributed to the COTP surface assuming a negative charge at this pH, as evidenced by pHpzc analysis, while TMX concurrently exists in the TMX+ form in solution. The resulting electrostatic attraction between TMX+ and the negatively charged COTP surface promotes oxidation. In addition, hydroxyl radicals (OH•) play a significant role in TMX degradation at neutral and alkaline pH. Nevertheless, increasing the pH above 7 results in a marked decrease in degradation efficacy, likely due to increased electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged COTP surface and the TMX molecules present at these higher pH values. Overall, the most effective TMX degradation in this study was observed to occur under neutral pH conditions.

Effect of COTP dose

The impact of photocatalyst loading on the degradation kinetics of TMX is detailed in Fig. 11, which presents data for COTP concentrations between 0.02 g/L and 0.06 g/L. The results indicate that increasing the COTP concentration from 0.02 g/L to 0.04 g/L markedly improved the photocatalytic degradation rate, enhancing the removal rate from 55% to 97%, under controlled conditions (pH 7, visible light source: 50 W LED lamp, irradiation time: 60 min). The observed increase in kTMX values, peaking at approximately 0.04 g/L, is attributed to the greater availability of catalytic surface area and active sites. This promotes the generation of photocatalytically active species on the catalyst surface, leading to a higher concentration of reactive oxidizing agents, including electron holes, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide radicals, which are crucial for efficient TMX photodegradation. However, increasing the catalyst concentration beyond 0.04 g/L led to a decline in degradation efficiency at 0.06 g/L, likely due to increased turbidity of the reaction mixture. These findings suggest that 0.04 g/L is the optimal photocatalyst concentration for this system.

Photostability and reusability of COTP

To minimize expenses and prevent secondary pollution, two essential factors- stability and reusability- were prioritized in the assessment of the photocatalytic materials used in practical applications. Accordingly, TMX degradation experiments were conducted over five consecutive cycles (Fig. 12). To ensure sufficient photocatalyst availability for the final cycle, five separate batches underwent identical TMX photocatalytic degradation tests under controlled conditions. In each batch, 0.04 g/L of the synthesized COTP was mixed with 100 mL of TMX solution at a concentration of 10 mg/L. After completing all degradation tests, the COTP samples were collected, filtered, dried, and weighed (with an approximate loss of 10 mg) to prepare for the initial cycle experiment. The recovered COTP was sufficient to perform the five initial cycle experiments, after which the COTP was collected again to carry out the second cycle using the same methodology. This procedure was repeated until the final cycle was completed. Throughout these cycles, conducted under identical conditions, a slight decline of only 13.6% in TMX degradation efficiency was observed, demonstrating the excellent photostability and reusability of COTP.

Conclusion

The COTP photocatalyst was synthesized via a reflux method under a nitrogen atmosphere using two precursors, TAT and PTCDA. The resulting material was characterized by TEM, FESEM, EDS, XRD, FT-IR, and DRS techniques. UV–Vis DRS analysis determined the band gap of the synthesized COTP to be 2.4 eV. The photocatalyst was then applied to the degradation of TMX in water, demonstrating optimal efficiency at pH = 7.0, with in an initial TMX concentration of 10 mg/L, and a COTP dose of 40 mg/L, under visible light irradiation. Moreover, an analysis of the reaction dynamics along with quenching experiments demonstrated the crucial role of e−, \(\:{\text{O}}_{2}^{{\cdot\:}-},\:\)and \(\:{\text{h}}^{{\cdot\:}}\) groups in the degradation of TMX molecules. Furthermore, findings indicated that the COTP photocatalyst exhibited good reusability, maintaining a TMX degradation efficiency of 83% within 60 min over five consecutive cycles, underscoring its stability. For future research, exploring novel covalent organic polymer photocatalysts is recommended to further advance solutions for water treatment and clean energy production.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

References

Zandipak, R. & Sobhanardakani, S. Novel mesoporous Fe3O4/SiO2/CTAB–SiO2 as an effective adsorbent for the removal of amoxicillin and Tetracycline from water. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 20, 871–885 (2018).

Shen, X., Zhang, J. & Zheng, H. RhB-sensitized MIL-125(Ti)/g-C3N4/Bi2O3 composite for adsorption and visible-light photocatalytic removal of drugs from water. Colloids Surf., A. 709, 136089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.136089 (2025).

Ahmed, I. & Jhung, S. H. Nanoarchitectonics of porous carbon derived from urea-impregnated microporous triazine polymer in KOH activator for adsorptive removal of sulfonamides from water. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 143, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2024.08.041 (2025).

Zhang, H., Zhao, Y., Wang, C., Liu, B. & Yu, Y. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by Boron nitride loaded with Co mixed oxides and Boron vacancy for ultrafast removal of drugs in surface water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114241 (2024).

Khaleeq, A., Tariq, S. R. & Chotana, G. A. Fabrication of samarium doped MOF-808 as an efficient photocatalyst for the removal of the drug Cefaclor from water. RSC Adv. 14, 10736–10748. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra00914b (2024).

Fang, X. et al. g-C3N4/polyvinyl alcohol-sodium alginate aerogel for removal of typical heterocyclic drugs from water. Environ. Pollut. 319, 121057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121057 (2023).

Fahmy, L. M., Mohamed, D., Nebsen, M. & Nadim, A. H. Eco-friendly tea waste magnetite nanoparticles for enhanced adsorptive removal of Norfloxacin and Paroxetine from water. Microchem. J. 206, 111619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2024.111619 (2024).

Ghoochian, M., Panahi, H. A., Sobhanardakani, S., Taghavi, L. & Hassani, A. H. Synthesis and application of Fe3O4/SiO2/thermosensitive/PAMAM-CS nanoparticles as a novel adsorbent for removal of Tamoxifen from water samples. Microchem. J. 145, 1231–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2018.12.004 (2019).

Paşa, S., Yılmaz, N., Bulduk, İ. & Alagöz, O. Effective adsorption performance of hemp root-derived activated carbon for tamoxifen-contaminated wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 425, 127219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2025.127219 (2025).

Ferrando-Climent, L. et al. Elimination study of the chemotherapy drug Tamoxifen by different advanced oxidation processes: transformation products and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 168, 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.057 (2017).

Castellano-Hinojosa, A. et al. Anticancer drugs alter active nitrogen-cycling communities with effects on the nitrogen removal efficiency of a continuous-flow aerobic granular sludge system. Chemosphere 376, 144279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2025.144279 (2025).

Cheraghi, M. Synthesis of GO/Fe3O4-ZnO/CS nanocomposite as an ideal adsorbent for removal of Tamoxifen from water. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102, 7135–7154. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2020.1826462 (2022).

Teunissen, S. F., Rosing, H., Schinkel, A. H., Schellens, J. H. M. & Beijnen, J. H. Bioanalytical methods for determination of Tamoxifen and its phase I metabolites: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 683, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2010.10.009 (2010).

Borgatta, M., Decosterd, L. A., Waridel, P., Buclin, T. & Chèvre, N. The anticancer drug metabolites Endoxifen and 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen induce toxic effects on daphnia pulex in a two-generation study. Sci. Total Environ. 520, 232–240 (2015).

Gjerde, J. et al. Identification and quantification of Tamoxifen and four metabolites in serum by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1082, 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2005.01.004 (2005).

Drooger, J. C. et al. Development and validation of an UPLC–MS/MS method for the quantification of Tamoxifen and its main metabolites in human scalp hair. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 114, 416–425 (2015).

Haidary, S. M., Mohammed, A. B., Córcoles, E. P., Ali, N. K. & Ahmad, M. Effect of coatings and surface modification on porous silicon nanoparticles for delivery of the anticancer drug Tamoxifen. Microelectron. Eng. 161, 1–6 (2016).

Sobhan Ardakani, S., Cheraghi, M., Jafari, A., Zandipak, R. & and PECVD synthesis of ZnO/Si thin film as a novel adsorbent for removal of Azithromycin from water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102, 5229–5246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2020.1793973 (2022).

Zandipak, R. et al. Synergistic effect of graphitic-like carbon nitride and sulfur-based thiazole-linked organic polymer heterostructures for boosting the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in water. Chem. Eng. J. 494, 152843 (2024).

Xu, Y., Jin, S., Xu, H., Nagai, A. & Jiang, D. Conjugated microporous polymers: design, synthesis and application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 8012–8031 (2013).

Yu, S. Y. et al. Direct synthesis of a covalent triazine-based framework from aromatic amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8438–8442. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201801128 (2018).

Zandipak, R., Bahramifar, N., Younesi, H. & Zolfigol, M. A. Decoration of carbon nanodots on conjugated triazine framework nanosheets as Z-scheme heterojunction for boosting opto-electro photocatalytic degradation of organic hydrocarbons from petrochemical wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13, 115380 (2025).

Wang, Z., Zhang, S., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z. & Ma, S. Covalent organic frameworks for separation applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 708–735 (2020).

Zandipak, R., Bahramifar, N., Younesi, H. & Zolfigol, M. A. Electro-photocatalyst effect of N-S-doped carbon Dots and covalent organic triazine framework heterostructures for boosting photocatalytic degradation of phenanthrene in water. Chemosphere 364, 142980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142980 (2024).

Lohse, M. S. & Bein, T. Covalent organic frameworks: structures, synthesis, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1705553 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Covalent organic framework as an efficient, metal-free, heterogeneous photocatalyst for organic transformations under visible light. Appl. Catal. B. 245, 334–342 (2019).

Ma, Z. et al. Efficient decontamination of organic pollutants from wastewater by covalent organic framework-based materials. Sci. Total Environ. 901, 166453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166453 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Regulating donor-acceptor interactions in triazine-based conjugated polymers for boosted photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B. 312, 121374 (2022).

Sheng, Y., Li, W., Zhu, Y. & Zhang, L. Ultrathin perylene Imide nanosheet with fast charge transfer enhances photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B. 298, 120585 (2021).

Hassan, A., Alam, A., Ansari, M. & Das, N. Hydroxy functionalized triptycene based covalent organic polymers for ultra-high radioactive iodine uptake. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 130950 (2022).

Athar, M. S. et al. Z-scheme designed LaNiO3/g-C3N4/MWCNT nanohybrid with bifunctional photocatalytic applications under visible light. Mater. Today Sustain. 26, 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100779 (2024).

Nasseh, N., Al-Musawi, T. J., Miri, M. R., Rodriguez-Couto, S. & Panahi, A. H. A comprehensive study on the application of FeNi3@SiO2@ZnO magnetic nanocomposites as a novel photo-catalyst for degradation of Tamoxifen in the presence of simulated sunlight. Environ. Pollut. 261, 114127 (2020).

Arghavan, F. S. et al. Complete degradation of Tamoxifen using FeNi3@SiO2@ZnO as a photocatalyst with UV light irradiation: a study on the degradation process and sensitivity analysis using ANN tool. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 128, 105725 (2021).

Nasseh, N., Samadi, M. T., Ghadirian, M., Panahi, A. H. & Rezaie, A. Photo-catalytic degradation of Tamoxifen by using a novel synthesized magnetic nanocomposite of FeCl2@ac@ZnO: a study on the pathway, modeling, and sensitivity analysis using artificial neural network (AAN). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107450 (2022).

Rashtchi, N., Sobhanardakani, S., Cheraghi, M., Goodarzi, A. & Lorestani, B. High-efficient photocatalytic degradation of Tamoxifen and doxorubicin by novel ternary heterogeneous GO@Fe3O4@CeO2 photocatalyst. Toxin Reviews. 42, 701–708 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all supporting organizations for providing facilities to conduct and complete this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Seyed Mohammad Amir Shah Karami, Soheil Sobhanardakani, Mehrdad Cheraghi, Bahareh Lorestani, and Atefeh Chamani. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Seyed Mohammad Amir Shah Karami and Soheil Sobhanardakani, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. The corresponding author ensured that all the listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission, including the metadata.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All authors have read, understood, and complied with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of Authors” as found in the Instructions for Authors. They are aware that, with minor exceptions, no changes can be made to authorship once the paper is submitted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amir Shah Karami, S.M., Sobhanardakani, S., Cheraghi, M. et al. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of tamoxifen using covalent organic triazine polymer. Sci Rep 15, 43331 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27281-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27281-6