Abstract

Porous composites can store and release lubricants via their unique pore structures, enabling continuous lubrication for self-lubricating bearing cages. In this study, carbon nanotube (CNT)/polyether ether ketone (PEEK) porous self-lubricating bearing cage materials were fabricated using the fused deposition molding (FDM) technique. Their preparation process, microstructure, and properties were systematically investigated. The results demonstrate the initial feasibility of preparing CNT-reinforced PEEK porous composites via FDM with optimized parameters. The incorporation of CNTs effectively modulated the material’s structure, increasing the average pore size from 0.08 μm to 11.62 μm and optimizing the porosity within a specific content range. However, higher CNT content resulted in poor extrusion flowability and nozzle clogging. Nevertheless, CNTs significantly enhanced the material’s tribological performance while maintaining good mechanical properties. This study provides a theoretical basis and process reference for preparing self-lubricating bearing cages, while also identifying that process optimization and CNT dispersion require further in-depth investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of high-speed rail, aviation, and aerospace fields is subjecting high-performance equipment to increasingly demanding operating conditions1. As critical supporting components in high-end mechanical systems, the performance of bearings and bearing units directly dictates the overall service life of the equipment. Research has indicated that lubrication failure is a leading cause of bearing failure. This is exemplified by dozens of documented satellite failures attributed to lubricant failure within bearing assemblies2. In 2005, a specific aircraft model experienced a severe incident. The investigation concluded that wear on the main shaft bearing raceway and a fractured cage led to a catastrophic failure of the main shaft3.These cases demonstrate the inadequacies of traditional lubrication technologies when applied to high-performance mechanical systems.

Scholars widely agree that porous self-lubricating materials offer a promising solution for bearing cages. Lubricant stored within the porous network of the cage is released onto the friction pair during operation, driven by centrifugal force and thermal effects. This mechanism provides continuous lubrication, thereby achieving the goal of reducing friction and wear4,5,6. Common types of self-lubricating materials include polymers (such as PEEK, PTFE, and PI), metal-matrix composites (e.g., copper-based and iron-based), and ceramic-matrix composites (e.g., silicon carbide and silicon nitride)7. Poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK), a semi-crystalline high-performance thermoplastic, is widely used in aerospace, medical, and energy sectors due to its exceptional mechanical properties, high-temperature resistance, and chemical stability. Furthermore, its excellent processability and tribological performance make it a premier candidate for fabricating porous cages8,9,10,11..

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are often used as reinforcing fillers for PEEK-based composites due to their high aspect ratio and excellent mechanical properties12. The research shows that the comprehensive properties of the composites can be effectively improved by filling it into the polyetheretherketone (PEEK) matrix after reasonable surface treatment13,14. Ata et al.15 studied the mechanical properties of CNT reinforced PEEK. It was found that when the CNT content was 5 wt %, the tensile strength of the composite reached 112 MPa, which was about 24% higher than that of pure PEEK (~ 90 MPa). Hou et al.16 compared the properties of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) reinforced PEEK under different molding processes. Under the condition of compression molding, when the content of CNTs was 4 wt %, the flexural strength of the composites reached 338.5 MPa, which was 46.9% higher than that of pure PEEK (230.4 MPa).Under the condition of injection molding, when the content of CNTs was 4 wt %, the tensile strength (101.09 MPa) was 23% higher than that of pure PEEK (82.19 MPa), and the bending strength (280.65 MPa) was 37.7% higher than that of pure PEEK (203.88 MPa). Ye Xin17 prepared CNTs/PEEK composites by 3D printing technology. The tensile strength of CNTs/PEEK composites was 107.7 MPa, which was 27.4% higher than that of pure PEEK materials. The above studies have confirmed that CNTs as a reinforcing phase can effectively improve the mechanical properties of PEEK-based composites. However, these studies did not address the properties of porous CNTs/PEEK composites.

At present, the main preparation processes of porous self-lubricating bearing materials are cold pressing sintering method and template-filtration method. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) is one of the most commonly used printing technologies in additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing) technology. FDM technology constructs three-dimensional objects by depositing molten materials layer by layer. This layer-by-layer construction method enables flexible adjustment of material composition and printing parameters in the manufacturing process, which provides the possibility for customization and optimization of high-performance composite materials18,19,20.

In this study, CNTs reinforced PEEK based porous self-lubricating bearing cage materials were prepared by melt deposition-water washing method. On this basis, the porous self-lubricating bearing cage material was prepared by FDM. Based on the previous research on the sample combination with excellent comprehensive performance (50% NaCL porogen + 50% PEEK)21[,22[,23. This work systematically investigates how preparation parameters dictate the microstructure of porous self-lubricating materials and, consequently, their mechanical and tribological properties. The findings provide a theoretical foundation for the integrated design and fabrication of porous self-lubricating bearing cages tailored for specific performance requirements.

Materials and methods

Preparation of composite wire

Pretreatment of composite powder

To enhance the interfacial bonding between CNTs and the matrix material and prevent CNT agglomeration in porous parts—which can adversely affect pore formation—the powder underwent pretreatment involving surface modification, particle size control, and dispersion optimization.

PEEK powder was supplied by Jilin Warnat Polymer Co., Ltd., with a particle size of 200 mesh, a density of 1.3 g/cm³, and a melting point of 334 °C. CNTs (TNMC7) were provided by Chengdu Zhongke Time Nano Technology Co., Ltd.; their main parameters are listed in Table 1. Sodium chloride (NaCl) powder was obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., with a density of 2.1 g/cm³ and a melting point of 804 °C. The NaCl powder was sieved through a 325 mesh screen.

The CNT pretreatment procedure was as follows: First, the CNTs were reflux-cleaned in acetone, rinsed with ethanol, and then dried at 120 °C to remove sizing agents and surface contaminants. Subsequently, they were subjected to ultrasonic dispersion for 5 h to improve dispersibility, followed by oven drying for later use.

The nano-calcium carbonate was also modified for subsequent application. It was first dispersed in deionized water via ultrasonication for 30 min and then heated to 90 °C in a water bath. Molten sodium stearate was added to the slurry, and the reaction was maintained at 90 °C for 2 h before filtration. The resulting filter cake was washed with a hot anhydrous ethanol solution, dried, ground, and sieved.

The specific mass ratios of PEEK/NaCl and the CNT addition amounts are provided in Table 2 According to this table, appropriate quantities of NaCl and PEEK powder (both pre-dried at 120 °C for 12 h) were accurately weighed. The pretreated CNTs were also weighed and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 6 h. Based on 0.5 wt% and 1 wt% of the total composite PEEK/NaCl powder mass, cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid diisononyl ester and modified nano-calcium carbonate were weighed. The PEEK/CNT/NaCl mixture was then blended with these additive powders (cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate and modified nano-calcium carbonate) in a ball mill for 8 h. Finally, the mixed powder was dried in an oven at 120 °C for 10 h.

Preparation of composite wire

The composite filament was prepared via a melt-blending extrusion process, with the temperature settings for each zone of the twin-screw extruder carefully controlled. Using the preparation of the composite filament for sample CN3#−1 as an example, the specific temperatures for each extruder zone are provided in Table 3 The prepared filament was stored in a 60 °C drying oven.

Preparation of porous samples

The FDM process was performed using an ENGINEER Q300 rapid prototyping system (Shaanxi Jugao Additive Intelligent Manufacturing Technology Development Co., Ltd., Weinan, China). The process parameters were as follows: nozzle diameter of 1.0 mm, nozzle temperature of 420 °C, platform temperature of 75–85 °C, ambient chamber temperature, printing speed of 30 mm/s, and layer thickness of 0.2 mm. The preparation process is shown in Fig. 1.

Removal of NaCL porogen

The sample was subsequently subjected to ultrasonic cleaning for 48 h, accompanied by mechanical stirring to facilitate the removal of the internal pore-forming agent, NaCl. After cleaning, the sample was placed in an oven for low-temperature drying over 5 h.

Performance test

Structural characteristics

The filamentation properties and printing properties of CNTs/PEEK composite powders were observed. The macroscopic morphology of the fibers was observed by optical microscope. The microstructure of CNTs reinforced PEEK matrix composites was observed by laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM, Zeiss-LSM800, Chernenko, Germany). The field emission scanning electron microscope (EDS, JSM-IT800, Tokyo Electronics Co., Ltd., Japan) was used to test the removal effect of Nacl inside the sample. The pore size and porosity distribution of CNTs-reinforced PEEK porous samples were tested using a mercury pore size meter (Mike, Autopore IV 950).

High temperature tribological performance test

The friction and wear properties of the material under dry friction conditions were tested using a high temperature friction and wear tester (Lanzhou Zhongke Kaihua Technology Development Co., Ltd., HT-1000, Lanzhou, China). The test conditions are set as follows : the diameter of the grinding ball is 5 mm, the material of the steel ball is 9Cr18, the applied load is 5 N, the friction radius is 5 mm, the rotation speed is set to 392 r/min, and the test time is 30 min.

Mechanical performance test

In order to study the mechanical properties of CNTs reinforced PEEK porous samples, Shore hardness tester (TIME5410 type) was used for testing. The bending strength and tensile strength of porous PEEK materials were tested by electronic universal testing machine (UTM5305 type). The mechanical performance test standard of the sample is shown in Table 4.

Result

Composite wire preparation performance

Preparation properties of composite materials

The preparation parameters for composite powder melt-blending extrusion and FDM printing are summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5 shows that the extrudability of the composite filament decreases with increasing CNT content. This trend is attributed to the rise in melt viscosity caused by a higher proportion of CNTs, which impairs extrusion flowability. Furthermore, the addition of CNTs altered the rheological behavior of the composite, enhancing its non-Newtonian characteristics and resulting in poorer fluidity.

As shown in Table 6, an increase in CNT content adversely affects the printing process and the surface quality of the printed parts. Specifically, the smoothness of filament feed and retraction decreases, leading to rougher part surfaces. The incorporation of CNTs alters material properties such as the coefficient of thermal expansion and shrinkage, preventing uniform contraction and expansion during the molding process and resulting in warpage. To address this issue, a substrate modification technique was adopted, which involved using a glass substrate with an adhesive film to enhance the adhesion between the printing layer and the substrate, thereby preventing warpage.

Macroscopic and microscopic morphology of composite wire

Macroscopic morphology of composite wire

The surface and fracture morphology of the composite filaments were observed using an optical microscope (Figs. 2 and 3).

As shown in Fig. 2, for 1:1 mass ratio of NaCl to PEEK, an increase in CNT content significantly worsened the filament surface roughness and adversely affected its FDM printability. Furthermore, the winding performance and diameter controllability of the filament deteriorated with the incorporation of CNTs. The primary reason for these phenomena is that the CNTs impaired the flow behavior of the composite material. This effect was more pronounced at a CNT mass fraction of 3%, where severe agglomeration occurred, further increasing the surface roughness and reducing the flexibility of the filament.

Figure 3 shows that the fracture morphology of the filaments, across different CNT mass fractions, exhibits relatively uniform protrusions, pore sizes, and distribution.

Microstructure of CNTs reinforced PEEK-based porous materials

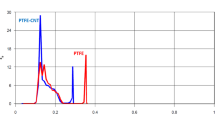

The porous structure of the CNT-reinforced PEEK composites was analyzed using laser confocal scanning microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 4). The elemental content of the porous sample after NaCl removal was subsequently determined by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Fig. 5). Finally, key microstructural parameters, including pore size and porosity, were characterized using mercury intrusion porosimetry (Fig. 6).

The distribution and size of microscopic pores within the porous material are key factors governing its macroscopic properties. The results in Fig. 4 reveal a uniform internal pore distribution and good interconnectivity within the CNT-reinforced PEEK structure after NaCl leaching. This indicates that the excellent pore-forming capability of the NaCl agent was not compromised by the incorporation of CNTs. This successful pore formation is attributed to the inherent suitability of NaCl as a porogen and the uniform particle size achieved by sieving, which enables the preparation of composites with abundant, controllable porosity.

EDS analysis (Fig. 5) confirmed that the NaCl pore-forming agent was almost entirely removed via the aqueous leaching process under the experimental conditions. This result indicates that the introduction of CNTs did not impede the removal of NaCl from within the porous PEEK matrix. Consequently, CNT-reinforced PEEK porous composites can effectively avoid the detrimental effects of residual pore-forming agent, ensuring the material’s good applicability.

As shown in(6- a), the incorporation of CNTs significantly increased the average pore size of the porous PEEK materials. When the CNT mass fraction reached 3%, the average pore size increased markedly from 0.08 μm (without CNTs) to 11.62 μm. This phenomenon can be attributed to the following mechanism: the addition of CNTs reduced the flowability of the composite melt, which promoted the agglomeration of NaCl particles. Consequently, after the removal of NaCl, a significant increase in pore size was observed.

The results(6- b) in demonstrate that introducing an appropriate amount of CNTs considerably enhances the material’s porosity. At a CNT mass fraction of 1%, the porosity increased from 12.92% to 28.50%, representing an increase of 120%. This change is primarily due to two synergistic effects: (1) the micron-sized pore structure formed by the NaCl particles within the PEEK matrix, and (2) the unique hollow tubular structure of the CNTs, which acts as a ‘nano-bridge’ to effectively interconnect adjacent pores, thereby constructing a three-dimensional network.

However, when the CNT mass fraction was further increased to 3 wt%, the porosity of the porous material decreased to 18.14%. This reduction is caused by the severe impairment of composite fluidity at high CNT loading, which affects the dispersion uniformity of both NaCl and CNTs. The aggravated agglomeration of both components compromises pore connectivity, ultimately leading to a decrease in overall porosity. In summary, while CNT addition significantly influences the microstructure of porous PEEK, the porosity does not increase monotonically with CNT content but exhibits an optimal range. By rationally designing the filament composition and processing parameters, porosity can be controlled, and the pore-forming effect can be optimized.

Properties of CNTs reinforced PEEK-based porous composites

Mechanical property

The mechanical behaviors were systematically evaluated to investigate the regulatory effect of CNTs on the macroscopic properties of the porous materials. The combined property and porosity data reveal a clear trend: the incorporation of CNTs optimizes the pore structure while forming a complex interplay with the matrix, which collectively governs the final mechanical performance of the materials Fig.7.

Specifically, the baseline sample without CNT addition (3#) exhibited a flexural strength, hardness, and tensile strength of 44.1 MPa, 80.3 HD, and 22.7 MPa, respectively, corresponding to a porosity of 12.92%. Upon introducing 0.5 wt% CNTs (sample CN3#−1), the material’s porosity increased significantly to 24.92%. This highly porous structure enhanced stress concentration effects, leading to a reduction in flexural strength and hardness to 31.8 MPa and 74.7 HD, respectively. It is noteworthy that despite the detrimental effect of high porosity on mechanical properties, the reinforcing role of CNTs began to manifest in the tensile performance, with a slight increase in strength to 23.14 MPa.

When the CNT content was increased to 1 wt% (sample CN3#−2), the porosity reached its peak value of 28.5%. At this concentration, an optimal balance was achieved between the reinforcing effect of the CNTs and the weakening effect of the pores: the flexural strength recovered to 36.4 MPa, the hardness returned to 79.6 HD (approaching the baseline level), and the tensile strength peaked at 27.11 MPa, representing a significant increase of 19.4% compared to the baseline sample. This phenomenon underscores the effectiveness of CNT reinforcement, demonstrating that their introduction can enhance the overall mechanical performance even under high porosity conditions. For instance, in a previous study, sample 4# without CNTs and with a porosity of 23.65% exhibited a hardness of only 73 HD. In contrast, the CN3#−2 sample in this work, despite having a higher porosity (28.5%), achieved a hardness of 79.6 HD, convincingly demonstrating the reinforcing contribution of the CNTs.

From a microstructural perspective, a plausible explanation for the improved tensile strength is that the carboxylated CNTs formed stronger interfacial bonding with the PEEK matrix during melt blending, thereby enhancing stress transfer. However, it must be noted that the chemical state of the interface was not characterized in this study; therefore, this mechanism requires validation through direct evidence.

When the CNT content was further increased to 3 wt% (sample CN3#−3), excessive CNTs induced severe agglomeration. This not only blocked pore channels, causing the porosity to decrease to 18.14%, but also created numerous stress concentration points within the matrix, leading to the deterioration of all mechanical properties: the flexural strength, hardness, and tensile strength dropped to 27.8 MPa, 73.4 HD, and 25.08 MPa, respectively. It should also be noted that the dispersion and orientation of CNTs within the matrix significantly influence the mechanical properties of composites. In this study, the dispersion and orientation of CNTs in the prepared composites exhibited a certain degree of randomness, which could be a factor affecting the stability of the mechanical properties.

In summary, the mechanical properties of the CNT-reinforced porous PEEK materials are governed by the combined effects of porosity and CNT reinforcement efficiency. Under the conditions of this study, a CNT content of 1 wt% resulted in the most favorable mechanical performance, providing critical insight for subsequent material design and optimization.

(2) Friction performance.

Under extreme operating conditions such as ultra-high vacuum, alternating high and low temperatures, and frequent start-stop cycles, lubricant depletion between friction pairs is accelerated, resulting in aerospace bearings operating under dry friction conditions. Accordingly, this study focuses on the most challenging dry friction conditions encountered in practical applications, with no investigation into boundary lubrication or fluid-film lubrication states. The tribological properties of porous materials under dry friction conditions were systematically investigated.

The friction coefficient curves obtained under dry friction conditions using a high-temperature tribometer are presented in Fig. 8, while the corresponding average friction coefficients are summarized in Fig. 9.

Figure 8 demonstrates that under dry friction conditions, the friction coefficient of the CNT-reinforced PEEK composites stabilized during a much shorter running-in period compared to the pure PEEK samples. This improvement can be attributed to two primary factors. First, the high strength and rigidity of CNTs enable them to effectively bear and distribute external load, thereby increasing the actual contact area. Second, the excellent thermal conductivity of CNTs allows for efficient transfer and dissipation of frictional heat, reducing thermal wear. Moreover, CNT wear debris may act as a solid lubricant. In summary, the incorporation of CNTs effectively enhances the tribological performance of PEEK-based porous materials.

Figure 9 indicates that the friction coefficients under high-temperature dry friction conditions were consistently higher than those at room temperature. The intense friction generates substantial heat, leading to a continuous rise in localized temperature, which can induce adhesion between the contacting surfaces and consequently increase the friction coefficient. With the incorporation of CNTs, the friction coefficients of the PEEK-based porous composites exhibited a decreasing trend, with a maximum reduction of 31.71%. At room temperature, the friction coefficient decreased significantly with increasing CNT content: sample CN3#−3 showed the highest reduction of 63.4%, while CN3#−2 exhibited the smallest reduction of 30.9%. These results collectively demonstrate that CNT addition effectively enhances the tribological properties of PEEK-based porous materials and improves their friction stability at elevated temperatures.

For porous materials, the macroscopic friction performance is affected by the synergistic effect of many factors such as material density, pore size and porosity. It is difficult to independently analyze any of the factors in the specific analysis. The limitation of this study is that we studied the preparation method of CNTs reinforced PEEK composites, the effect of sample porosity on its mechanical properties and the dry friction properties of the samples, but did not avoid the agglomeration of CNTs with high mass ratio and did not get the optimal addition amount of CNTs. In addition, the self-lubricating performance of bearing cage needs further study on its oil content, oil retention rate and oil friction. Therefore, the friction properties of the materials prepared in this study need to be further studied.

Conclusions

This study investigates the feasibility of fabricating carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced PEEK-based porous composites using fused deposition modeling (FDM). Composite samples were prepared through powder-based filament formation, with NaCl pore-forming agents removed via an aqueous leaching method. The effects of different CNT contents on the properties of PEEK-based porous samples were systematically studied, leading to the following main.

(1) Using optimized FDM parameters, structurally intact PEEK-based porous samples with higher porosity reinforced by CNTs were successfully prepared, preliminarily validating the feasibility of the “powder pretreatment-filament extrusion-FDM printing-aqueous pore-forming agent removal” process route. However, this process still faces challenges, including nozzle clogging, reduced extrusion flowability, and impaired filament flexibility at higher CNT contents.

(2) NaCl demonstrates excellent pore-forming capability in CNT/PEEK composites, enabling the formation of uniformly distributed micron-sized pore structures.

(3) The incorporation of CNTs effectively regulates material porosity and pore size, with the average pore size significantly increasing from 0.08 μm to 11.62 μm. However, porosity does not continuously improve with increasing CNT content, exhibiting an optimal addition range (0.5–1.5 wt% in this study). Excessive CNTs (e.g., 3 wt%) cause agglomeration that compromises pore connectivity, ultimately reducing porosity.

(4) The mechanical properties of CNT-reinforced PEEK porous materials show an initial improvement followed by deterioration with increasing CNT mass fraction, while tribological performance demonstrates notable enhancement. However, excessive CNT addition significantly reduces flexural strength, hardness, and tensile strength due to agglomeration issues.

(5) This study has several limitations: the agglomeration of CNTs at high mass fractions remains incompletely resolved, and the performance of porous materials under lubricated conditions (including oil content, retention rate, and boundary lubrication behavior) has not been systematically investigated. These aspects represent important directions for future research.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cai, X. C., Ma, S. H., Liang, M. G. & Ji, Z. J. Research progress on new materials and technologies for self-lubricating spherical plain bearing fabric liners. Lubr Eng. 50, 196–208 (2025).

Yadav, E. & Chawla, V. K. An explicit literature review on bearing materials and their defect detection techniques. Mater. Today Proc. 50, 1637–1643 (2022).

Li, S. H., Wei, C., Wu, Y. H. & Zhang, L. X. Research progress and key technologies of Si₃N₄ all-ceramic bearings for extreme working conditions. Bearing 9, 1–10 (2023).

Sun, J., Yan, K., Zhu, Y. & Hong, J. A high-similarity modeling method for low-porosity porous material and its application in bearing cage self-lubrication simulation. Materials 14, 5449 (2021).

[Marchetti, M., Jones, W. R. Jr., Pepper, S. V., Jansen, M. J. & Predmore, R. E. In-situ, on-demand lubrication system for space mechanisms. Tribol T. 46, 452–459 (2003).

Friedrich, K. Polymer composites for tribological applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 1, 3–39 (2018).

John, M. & Menezes, P. L. Self-lubricating materials for extreme condition applications. Materials 14, 5588 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Influences of cryo-thermal cycling on the tensile properties of short carbon fiber/polyetherimide composites. Compos Struct 344, 118336. (2024).

Li, P. X. et al. Research progress on biological 3D printing: additive manufacturing of animal, plant and microbial cells. J. Membr. Sci. 59, 237–252 (2023).

Wang, Q., Zheng, F. & Wang, T. Tribological properties of polymers PI, PTFE and PEEK at cryogenic temperature in vacuum. Cryogenics 75, 19–25 (2016).

Pei, X. & Friedrich, K. Sliding wear properties of PEEK, PBI and PPP. Wear 274, 452–455 (2012).

Robeson, L. M. Correlation of separation factor versus permeability for polymeric membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 62, 165–185 (1991).

Robeson, L. M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 320, 390–400 (2008).

Waidan, R., Ghanem, B. & Pinna, I. Fine-tuned intrinsically ultra microporous polymers redefine the permeability/selectivity upper bounds of membrane-based air and hydrogen separations. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 947–951 (2015).

Ata, S. et al. Improving thermal durability and mechanical properties of poly(ether ether ketone) with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Polymer 176, 60–65 (2019).

Hou, Y. J. Preparation and properties of polyetheretherketone/nanotube composites. (Dissertation, Dalian Polytechnic University, 2017).

Ye, X. Study on crystallization characteristics and fused deposition 3D printing performance of PEEK/CNTs materials. (Dissertation, Zhejiang Normal University, 2022).

Wang, P. et al. Preparation of short CF/GF reinforced PEEK composite filaments and their comprehensive properties evaluation for FDM-3D printing. Compos. B: Eng. 198, 108175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108175 (2020).

Zhang, Y. N. et al. Tensile and interfacial properties of polyacrylonitrile-based carbon fiber after different cryogenic treated condition. Compos. B: Eng. 99, 358–365 (2016).

Tian, G. Q. et al. Effect of FDM process parameters on dimensional accuracy of CF/PETG parts. Eng. Plast. Appl. 52 (8), 104–109 (2024).

Zhang, H., Duan, M., Qin, S. & Zhang, Z. Preparation and Modification of Porous Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) Cage Material Based on Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Polymers. 14, 5403 (2022).

Zhang, H., Duan, D. M., Qin, S. K., Zhang, Z. Z. & Deng, S. E. FDM Preparation of porous polyetheretherketone cage material and study on its tribological properties. Bearing 10, 57–62 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Study on mechanics and high temperature tribological properties of porous bearing cage material. J. Reinf Plast. Comp. 43, 1165–1178 (2024).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by Henan Provincial Natural Science Foundation [No. 252300421327].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B. and Z.Z. wrote the manuscript. W.X. and G.R. and D.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, B., Zhang, Z., Wang, X. et al. Preparation of CNT/PEEK porous composites via NaCl leaching and FDM for bearing cage applications. Sci Rep 15, 43083 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27346-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27346-6