Abstract

This study focused on manufacturing 3D printed conductive re-entrant (RE) midsoles with two slicing directions (horizontal and vertical) and three infill densities. Optimal 3D printing conditions were assessed through analyses of slicing processes, morphology, compressive and electrical properties, electromechanical property, and plantar pressure analysis. The analysis of the RE midsole was further divided into three parts: Meta (MT), Midfoot (MF), and Heel (HL). As results, horizontal direction (HD) layers were stacked horizontally, while vertical direction (VD) layers were deposited vertically, with VD being 1.5 times more rigid than HD. For VD, rigidity decreased in the order of MF > HL > MT, while for HD, it was HL > MF > MT. Both slicing directions showed similar electrical properties, with conductivity improving with higher infill density. The 50% infill density demonstrated the best electrical and electromechanical properties. Plantar pressure analysis revealed that HD provided a wider pressure area and better pressure distribution. Overall, HD midsoles with 50% infill density exhibited softer compressive property and superior electrical property during compression, offering better stability by distributing plantar pressure more effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The midsole is the most important functional part of a shoe, playing essential roles in body stabilization, shock absorption, cushioning, and rebound resilience. In addition, the pressure applied to the sole of the foot can be reduced by distributing the load to the sole of the foot. In order to provide these properties, a certain degree of elasticity and flexibility is required at the core of the shoe. Additionally, this can be achieved by providing cushioning through the hardness of the midsole1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Recently, research has been progressing on midsoles using meta-structures and biomimetic structures to provide these functions11,12,13,14,15. Especially, meta-structures are artificially designed structures with properties and functions that natural substances cannot achieve. Unlike traditional materials, the key features of meta-structures are expressed through intentionally designed repetitive structures rather than the properties of their constituent molecules16,17. Auxetic structures among meta-structures are noteworthy for their negative poisson’s ratio (NPR), which gives them unique mechanical characteristics. As a result, the arrangement, pattern, and repeating structure of a material play a crucial role in determining its physical properties18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Among auxetic structures, the re-entrant (RE) structure exhibits a negative inward angle, resulting in axial compression of the inwardly turned edges, resulting in NPR behavior. This structure offers superior indentation resistance, toughness, and energy absorption compared to other auxetic structures. Therefore, it is highly suitable for shoe midsoles, which require shock absorption against repeated impacts28,29,30,31. Recent studies have reported that applying RE structures to midsoles or insoles can reduce pressure and improve comfort, increase the contact area with the sole, and reduce peak pressure13,33,34,40. Furthermore, in recent years, electronic footwear has a function of analyzing the user’s health signal by integrating a sensor function. It can be manufactured in the form of an insole integrated with a sock and a sensor. The sensor is an elastomeric smart plantar sensing system and can be attached with a capacitive, piezoelectric, force-sensitive resistor, or pressure sensor10,11,12,13,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42.

Customization of midsole is an extremely important research field, as the core of a shoe requires a variety of designs depending on the shape and size of the wearer’s feet. This makes 3D printing very suitable for customized modeling manufacturing, which can easily represent different physical properties depending on the output conditions. FFF (Fused Filament Fabrication) 3D printing is a method where filament is melted and extruded through a nozzle, then layered to build up the object. This allows for easy printing of models43,44. Additionally, it can express various physical properties through the setting of processing conditions. 3D printing processing conditions, such as infill pattern, infill density, print orientation, layer height, print speed, nozzle temperature, and bed temperature, can be variously configured using a 3D slicing program or depending on the materials. Recently, many studies have been conducted on these output conditions and the performance evaluation of printed objects based on these conditions45,46,47,48. In particular, infill conditions determine the internal structure of the printed object and the nozzle’s movement path. Once the infill pattern is set, the infill density is chosen, ranging from 0% to 100%. Generally, lower infill density results in softer characteristics, while higher infill density leads to harder characteristics. Additionally, in FFF 3D printing, the printing direction is a crucial factor. The printing direction refers to the way and orientation in which the object is placed on the 3D printer’s bed. This determines the manner in which layers are stacked, significantly impacting the structural properties of the printed object49,50,51.

Recently, in a study developing shoe components using 3D printing, Leung et al.13 manufactured a heel pad with three re-entrant angles of 60°, 80°, and 90° using SLA 3D printers and flexible resins for use by diabetic mellitus patients. The results of the compression performance assessment show that flexible resin has elasticity and strength over conventional PU foam. And, when compressed to 750 N using various hardness hempisphere, the 80° re-entrant structure showed the most contact points with the compression ball. The contact point increased by more than 15% from 90°. On the other hand, it was confirmed that the lowest pressure value was identified during compression, which could provide optimal cushioning. Chen and Lee40 had shown the outsole designs with 3-, 4-, and 6-pointed star-shaped patterns and various thicknesses for 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0 mm, which were fabricated with a FDM 3D printer using lightweight TPU filament. The recovery absorption capacity of the prototypes was improved for adding thickness outsoles for n-pointed star-shaped outsoles. The static compressive confirmed with decreased tendency as the thickness increased, indicating the recovery absorption capacity was improved for adding thickness outsoles. In the case of surface pressure evaluation, the LW 3PS-10 presented the largest pressure area and lower pressure force, and was considered a comfort prototype. Therefore, the midsole should be able to disperse pressure exerted on the foot to reduce overall pressure.

Thus, in this research, conductive re-entrant (RE) midsole structure was manufactured according to the FFF 3D printing with various process conditions for checking the optimal 3D printing conditions. For manufacturing the midsole structure, the carbon black/TPU composite filament was used. In our previous research, this filament was confirmed the most suitable for 3D printed conductive structure52. And a RE pattern was applied. Also, the 3D printing conditions with various infill densities and printing directions were applied. For infill density, 20, 50, and 80% were applied. For printing direction, two options were used: vertical direction (VD) and horizontal direction (HD). Then, the re-entrant midsole structure was analyzed by slicing image analysis, compressive property, electrical property, electro-mechanical property, and plantar pressure analysis. Additionally, the performance of the RE midsole was assessed by dividing it into three parts: Meta (MT), Midfoot (MF), and Heel (HL). Our previous studies have investigated the electromechanical properties of 3D-printed structures using CB/TPU composite filaments, focusing on both re-entrant auxetic geometries and simple cubic unit cells with varying infill patterns52,53. These researches demonstrated that CB/TPU structures exhibited measurable electrical responses under mechanical deformation and hold potential for sensing applications. Building upon these findings, the present study expands the scope by implementing a full-scale midsole design based on the RE structure, aiming to evaluate not only compressive and electrical properties but also plantar pressure performance under simulated foot conditions. This multi-faceted approach bridges structural, electrical, and application perspectives to explore the feasibility of electrically functional midsoles for wearable applications.

Results and discussion

Analysis of slicing image and morphology

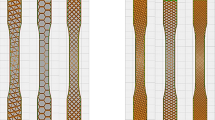

Figure 1a shows images of the RE midsole positioned in the VD and HD directions in the slicing program. Figure 1b appears the slicing images of the RE pattern for the midsole with different infill densities in both the VD and HD directions. Figure 1c depicts the scheme stacked on the RE structure. For the VD case, the interior of RE pattern was filled with a zigzag. Additionally, it was confirmed that the layers were stacked vertically in the RE pattern, with the pattern connected as layers of the same RE shape were stacked. For the HD case, the RE pattern was filled with layers internally. Also, the layers were stacked in the horizontal direction of the RE structure and that the structures were connected through infill.

Figure 1d illustrates the morphology of the 3D printed RE midsole structure with two types of print directions and 20% infill density. As confirmed in the morphology, in the VD case, the re-entrant structures were stacked vertically, while in the HD case, the RE structures were stacked horizontally. Therefore, it was confirmed that the output direction can affect compression and electrical characteristics.

Compressive property

Figure 2 displays the compressive stress-strain (S-S) curves of the 3D printed RE midsole with various infill densities and print directions. The initial modulus ranged from 0.03 MPa to 0.08 MPa. Specifically, the initial modulus of the midsole with MT was lower than that of MF and HL.

For the VD, the strength at 30% elongation varied with infill density was 0.03–0.05 MPa at VD20, 0.05–0.09 MPa at VD50, and 0.11–0.15 MPa at VD80. The strength increased as the infill density increased. By part, for VD20, the strength was highest in the order of MT > HL > MF. For VD50 and VD80, the order was MF > HL > MT. As the infill density increased, the middle part of the midsole became harder. There was a sharp increase in compressive strength at over 30% compression displacement. While the MF and HL regions exhibited a strong initial modulus, MT showed a higher rate of increase after 30%.

For the HD, HD20 was measured at 0.03–0.04 MPa, HD50 at 0.04–0.08 MPa, and HD80 at 0.05–0.13 MPa. Similar to VD, the strength increased with higher infill densities. In terms of strength by region, HD20 was hardest in MF, while HD50 and HD80 were firmest in HL. For all three infill densities, MT had the lowest strength. Additionally, after 40% compression strain for HD20 and after 30% compression strain for HD50 and HD80, the strength increased sharply. Although HD exhibited a larger initial modulus than VD, the rate of increase in stress with increasing compression strain was relatively smaller, indicating that HD is more elastic and softer. This was also confirmed in the slicing image, as HD was inferred to have layers deposited horizontally. Generally, samples stacked in the HD direction have reported wider outputted beads. Therefore, it can exhibit softer characteristics when compressed54,55. In addition, in FDM 3D printing, the direction of nozzle movement is determined by modeling and slicing conditions, which can affect mechanical property as layer bonding. It has been reported that improved layer bonding, depending on 3D printing process conditions, leads to improved mechanical strength and reduced voids56,57. Therefore, due to its lower compressive stress, HD was deemed more suitable for the RE midsole structure in terms of compression properties.

Electrical property

Figure 3 displays the electrical current-voltage (I-V) curves of the 3D printed RE midsole structure with various infill densities and print directions. At 10 V, the current values for VD samples consistently ranged from 0.04 to 0.05 A across all infill densities. For HD samples, the current values at 10 V were 0.03–0.04 A for HD20 and HD50, and 0.04–0.05 A for HD80. There were no significant differences based on infill density and print direction, although a slight increase in current values was noted with higher infill density. Previous research has shown that nozzle movement can influence fiber orientation and electrical anisotropy depending on the FDM 3D printing infill process conditions. Therefore, HD demonstrated superior conductivity as layers were stacked horizontally and RE patterns were connected through internal infill51,52,53.

Regarding current values by part, significantly higher values were observed in all samples, with HL > MF > MT. The HL pattern, containing the highest number of RE patterns among the parts, likely contributed to the increased amount of carbon material.

Electromechanical property

Figure 4 shows electromechanical curves of 3D printed RE midsole structure with various infill densities and print direction. The electro-mechanical properties during repeated compression were analyzed. After undergoing 5 compressions, VD samples showed current values of 0.01–0.04 A for 20% infill, 0.02–0.07 A for 50% infill, and 0.02–0.07 A for 80% infill. Similarly, in HD, current values ranged from 0.01 to 0.07 A for HD20, 0.01–0.10 A for HD50, and 0.01–0.09 A for HD80. All samples exhibited increased current values during compression, indicating enhanced conductivity as layer spacing decreased. In addition, HD samples demonstrated higher conductivity than VD samples. As confirmed in the slicing image and compressive property, it was inferred that HD can have narrower spacing between layers compared to VD because it was softer when compressed. Additionally, since HD was connected through filling the RE pattern, it appeared to be more effective when compressed. Regarding infill density, conductivity followed the order of 50% > 80% > 20%. This can be attributed to the compressive properties, where the 80% density allowed for closer layer spacing during compression compared to the 50% density.

Therefore, the change in current value during repeated compression was confirmed through electromechanical property analysis. In all samples, the current value increased during compression, it was indicated that the interlayer spacing was reduced and thus the conductivity was improved. In particular, as the HD sample was softer, the interlayer spacing could be narrower during compression than the VD sample, which could lead to a narrower interlayer spacing. Similarly, the 50% infill density sample showed the best conductivity due to the appropriate compressive strength and increased carbon material content. This can be confirmed to be the same tendency as that reported in a previous study, in which nonlinear hysteresis and gradual stabilization through stabilization were observed in 3D printed sensors made of TPU/Carbon materials under repeated deformation depending on the process, carbon material contents, and number of cycles58,59,60. Also, across different parts of the midsole, current values were measured in the order of HL > MF > MT. This corresponds with the number of RE patterns included in each part. The HL part, containing 25 patterns, likely contained the most carbon. Thus, it can be inferred that the HL part, with the highest content of conductive material, exhibited the best conductivity. However, since this study only performed five cycles, future studies will require extended cycles and long-term fatigue and hysteresis tests, including rate-dependence testing.

Plantar pressure analysis

Figure 5a show the results of the plantar pressure diagram conducted while maintaining a static posture for 10 s. Figure 5b presents the force percentage of plantar pressure analysis per four zones. And Fig. 5c illustrates the plantar pressure force during 10 s at 1-second intervals.

As shown in Fig. 5a, the plantar pressure diagrams revealed that the barefoot contacted with the ground across all three parts MT, MF, and HL, with the highest pressure applied to the HL part. VD showed a narrow pressure range, and as infill density increased, the foot almost didn’t touch the ground. Conversely, HD samples resembled the barefoot shape and distributed plantar pressure over a wider area. HD50 showed the closest resemblance to the bare foot, enabling all three parts to contact the ground and disperse pressure effectively. These results align with compression characteristics, where HD samples, being softer than VD, distributed plantar pressure over a wider range and provided more comfortable ground contact.

In Fig. 5b, comparing foot pressure across four areas, it was evident that the outside metatarsal Q2 and the inside heel experienced the highest pressure, accounting for over 60%. As shown in Fig. 5c, during static plantar pressure for 10 s, VD exhibited pressures of 130 N for 20%, 120 N for 50%, and 92 N for 80%. In HD, pressures reached up to 160 N for HD20, 125 N for HD50, and 120 N for HD80. While HD20 and VD20 samples showed unstable values, HD50, HD80, and VD80 maintained stable foot pressure over 10 s. This confirms that HD can maintain posture more stably, with HD50 being the most effective in distributing pressure exerted on the foot.

(a) Plantar pressure diagram of 3D printed RE midsole structure with two types of print direction and three types of infill density. (b) Force percentage of plantar pressure analysis per four zones of 3D printed RE midsole structure with two types of print direction and three types of infill density. (c) Plantar pressure force during 10 s of 3D printed RE midsole structure with two types of print direction and three types of infill density.

Conclusions

This study aimed to manufacture 3D printed conductive RE midsoles with two slicing directions and three infill densities. The optimal 3D printing conditions were determined through slicing process analysis, morphology, compressive property, electrical property, electromechanical property, and plantar pressure analysis.

Slicing image analysis and morphology examination confirmed that the layers of HD were stacked horizontally, while VD layers were deposited vertically. The compressive property results showed that VD was over 1.5 times more rigid than HD. Therefore, higher infill densities were deemed more suitable for HD midsoles due to their softer nature. For VD, rigidity followed the order of MF > HL > MT, while for HD, it was HL > MF > MT.

In terms of electrical property, the CB/TPU midsole showed similar tendencies and values between HD and VD, ranging from 0.03 to 0.05. Increasing infill density resulted in 1.2 times increase in current values, with conductivity being excellent in the order of HL > MF > MT. During compression, the electromechanical properties of the 50% infill density exhibited excellent conductivity. In the plantar pressure test, HD demonstrated a wider pressure area and well-distributed pressure.

Consequently, based on the RE structure, HD, with horizontally stacked layers, exhibited softer compression performance and superior electrical performance during compression. It also provided better stability by distributing plantar pressure over a wider range. Among these findings, it was evident that the 50% infill density showed the best electrical performance and most effectively distributed plantar pressure force. Furthermore, since the RE midsole’s electrical signal changes in response to mechanical deformation, it appears feasible to implement it as a piezoresistive sensor in the future. While this study demonstrated the potential of CB/TPU-based RE midsoles in terms of electrical and cushioning performance, the scope was limited to static conditions with a single participant. Future research plans to develop various midsole models and evaluate their performance based on plantar pressure data. Additionally, to further validate the applicability of this approach, further studies, including a broader range of participants and dynamic motion analyses, will be conducted to fully understand the impact of foot morphology, gait dynamics, and user variability on RE midsole performance. Also, this study plan to conduct durability evaluations under dynamic usage conditions to study the continued usability of the RE midsole. Furthermore, based on insights into print orientation and infill density, we aim to explore diverse midsole designs suitable for commercial and healthcare applications.

Methods

Materials

In order to fabricate the RE midsole, the carbon black (CB)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composite filament (Filaflex, Recreus, Spain) for FFF 3D printing was used. The hardness of the filament was measured at Shore 94 A for CB/TPU. The diameter and density were 1.75 mm and 1.35 g/cm3. The specific analysis of CB/TPU was proceeded in previous study50,51. Additionally, the composite filament was stored in a desiccator prior to print.

Fabrication of 3D printed RE midsole with various two types of print directions and three types of infill density

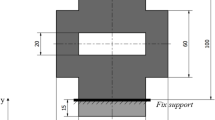

Figure 6 shows modeling images of RE midsole. The 3D modeling of RE midsole was taken from open source website61. For 3D printing, the FFF 3D printer (Single plus − 320 C, Cubicon Co., Ltd., Korea) was used. The following are the 3D printing processing conditions. The size of RE midsole was set at 235.00 × 80.43 × 39.70 mm3. The infill density was fixed to 20%, 50%, and 80%. And the identical infill pattern was applied to Zigzag which takes the short printing time. The nozzle temperature was set to 250 ℃. And the bed temperature was room temperature around 30 ℃ for CB/TPU. The printing speed was 60 mm/s.

Various 3D printing directions and detailed parts of the 3D printed RE midsole structure

Figure 7a shows slicing images and printed samples of RE midsole structure with various printing directions. Figure 7b indicates three parts of RE midsole structure. In order to check the optimal 3D printing output conditions, two output directions were set. The output direction was rotated based on the X axis. There are two output directions: Horizontal direction, which is the direction laid down based on the X-axis, and vertical direction, which is the direction where it is erected. The output times and weights are as follows: VD20 was 28 h (hours) 58 m (minutes) 4 s (seconds), VD50 was 32 h 53 m 06 s, and VD80 was 35 h 51 m 20 s. The printed weights are measured as 165.03 g, 179.76 g, and 203.16 g, respectively. For HD samples, the output times were confirmed to be 20 h 17 m 0 s for HD20, 22 h 33 m 51 s for HD50, and 25 h 08 m 18 s for HD80. The printed weights were measured to be 134.60 g, 153.99 g, and 192.33 g. Therefore, it was confirmed that both the output time and weight of the printed materials were greater for VD than for HD. In addition, the experiment was conducted by dividing the RE midsole into detailed three parts: meta (MT), midfoot (MF), heel (HL). The MT at the front of the foot included toes and metatarsals. The MF placed at the middle of the foot, including arch. The HL was at the back of the foot. The size of each part was 80 × 80 × 15 mm3 for MT, 80 × 80 × 25 mm3 for MF, and 80 × 65 × 25 mm3 for HL. Additionally, the number of included patterns was confirmed to be 11, 19, and 25. Sample code is shown Table 1.

Characterizations

The 3D printed RE midsole, with two types of print directions and three types of infill densities, was analyzed using various methods as slicing process, morphology, compressive property, electrical property, electromechanical property, and a plantar pressure test. The slicing image analysis was conducted using a slicing program, where the model was confirmed as solid on the print preparation screen after adjusting size and printing direction, focusing mainly on the infill, excluding the outer walls. Morphological examination was done using a fabric image analysis microscope (NTZ-6000, Nextecvision Co. Ltd., Korea) at a magnification of ×4.5, observing both the surface and cross-section, with the cross-section checked in the HL part after cutting the sample into three parts.

The compressive properties of the 3D printed RE midsole with two types of print directions and three types of infill densities were tested according to the KS M ISO 604 (Korean agency for technology and standards [KATS], 2018) standard. A compression test was performed using a universal testing machine (Instron 4201, Shimadzu, Japan) with a 5 kN load cell and a jig with a diameter of 100 mm and thickness of 15 mm. The compression direction was the -z direction, conducted at a speed of 100%/min, with the maximum displacement limited to 12.5 mm for compression up to 50% of the sample. A compressive stress-strain (S-S) curve was obtained to confirm the compressive initial modulus and stress at 50% compression. Each sample was measured three times, and the average value was used.

The electrical properties of the 3D printed RE midsole with two types of print directions and three types of infill densities were measured using a 2450 source measure unit (Keithley, USA). The current values were measured by holding the RE pattern in the middle of both sides with measuring clamps, with measurement positions indicated in (Fig. 7b). The voltage range of 0 to 10 V was measured at 0.5 V intervals, checking the current (A) at an applied voltage of 0 to 10 V. To minimize environmental effects on electrical measurements, all tests were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, maintaining a temperature of 25 ± 5 °C and relative humidity between 40 and 65%.

The electromechanical properties were confirmed during repeated compression, using a 2450 source measure unit (Keithley, USA) and a universal testing machine (Instron 4201, Shimadzu, Japan). The measuring voltage was applied at 5 V for 10 min, with repeated compression cycles applied 5 times at a compressive speed of 100%/min. The maximum stroke was 7.5 mm. The current (A) in the measuring voltage range during repeated compression cycles was confirmed. These electromechanical tests were also performed in a controlled environment, consistent with laboratory standards, to ensure result reliability.

Plantar pressure analysis was performed using a plantar pressure analyzer (Materialise, Belgium) and a Foot scanner (Alchemaker, Korea) program. One cycle of the experimental procedure consisted of static standing for 1 min, followed by a rest for 3 min. Only the right foot was measured, and the subject was confirmed to have a height of 155 cm, weight of 60 kg, and foot size of 225 mm.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author S. Lee (shlee014@dau.ac.kr) on reasonable request.

References

Tang, U. H. et al. Comparison of plantar pressure in three types of insole given to patients with diabetes at risk of developing foot ulcers – A two-year, randomized trial. J. Clin. Transl Endocrinol. 1, 121–132 (2014).

Shakouri, E., Mossayebi, A. & Saraeian, P. Fabrication of medical footwear for suitable distribution of stress and strain and reduction of plantar pressure by numerical and experimental approaches. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 223 (10), 1–13 (2019).

Tsai, Y. & Powers, C. M. Increased shoe sole hardness results in compensatory changes in the utilized coefficient of friction during walking. Gait Posture. 30, 303–306 (2009).

Lam, W-K., Ng, W. X. & Kong, P. W. Influence of shoe midsole hardness on plantar pressure distribution in four basketball-related movements. Res. Sports Med. 25 (1), 37–47 (2017).

Wong, P-L., Chamari, K., Mao, D. W., Wisloff, U. & Hong, Y. Higher plantar pressure on the medial side in four soccer-related movements. Br. J. Sports Med. 41 (2), 93–100 (2007).

Park, C-C. The effects of hardness on the compression-rebounding properties of shoe midsole. Elastomer 39 (3), 186–192 (2004).

Wit, B. D., Clercq, D. D. & Lenoir, M. The effect of varying midsole hardness on impact forces and foot motion during foot contact in running. J. Appl. Biomech. 11 (4), 395–406 (1995).

Cheung, J. T. M. & Zhang, M. Parametric design of pressure-relieving foot orthosis using statistics-based finite element method. Med. Eng. Phys. 30 (3), 269–277 (2008).

Chatzistergos, P. E., Naemi, R., Healy, A., Gerth, P. & Chockalingam, N. Subject specific optimization of the stiffness of footwear material for maximum plantar pressure reduction. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 45, 1929–1940 (2017).

Bickel, B. et al. Design and fabrication of materials with desired deformation behavior. ACM Trans. Graph. 29 (4), 63 (2010).

Chen, T., Tian, M. & Wang, X. A novel porous structural design of the orthotic insole for diabetic foot. In 2021 International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics 188–192 (2021).

Cheng, H., Liu, B., Liu, M. & Cao, W. Design of three-dimensional Voronoi strut midsoles driven by plantar pressure distribution. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 9, 1410–1429 (2022).

Leung, M. S., Yick, K., Sun, Y., Chow, L. & Ng 3D printed auxetic heel pads for patients with diabetic mellitus. Comput. Biol. Med. 146, 1055872 (2022).

Dehaghani, M. R., Nourani, A. & Arjmand, N. Effects of auxetic shoe on lumbar spine kinematics and kinetics during gait and drop vertical jump by a combined in vivo and modeling investigation. Sci. Rep. 12, 18326 (2022).

Riddick, R. C. et al. Stiffening the human foot with a biomimetic exotendon. Sci. Rep. 11, 22778 (2021).

Momeni, F., Hassni, S. M. M., Liu, X. & Ni, J. A review of 4D printing. Mater. Des. 122, 42–79 (2017).

Song, H. & Kim, J. 4D printing with smart materials and structures. Ceramist 23 (1), 27–37 (2020).

Ren, X., Das, R., Tran, P., Ngo, T. D. & Xie, Y. M. Auxetic metamaterials and structures - A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 27 (2), 023001 (2018).

Lakes, R. S. Negative poisson’s ratio materials - Auxetic solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 47, 63–81 (2017).

Bhullar, S-K. Three decades of auxetic polymers: a review. E-Polymers 15, 205–215 (2015).

Yang, C., Vora, H-D. & Chang, Y. Behavior of auxetic structures under compression and impact forces. Smart Mater. Struct. 27, 025012 (2018).

Novak, N., Vesenjak, M. & Ren, Z. Auxetic cellular materials: a review. Stroj Vestn - J. Mech. Eng. 62 (9), 485–493 (2016).

Kabir, S., Kim, H. & Lee, S. Physical property of 3D-printed sinusoidal pattern using shape memory TPU filament. Text. Res. J. 90 (21–22), 2399–2410 (2020).

Kabir, S., Kim, H. & Lee, S. Characterization of 3D printed auxetic sinusoidal patterns/nylon composite fabrics. Fibers Polym. 21 (6), 1372–1381 (2020).

Li, T., Liu, F. & Wang, L. Enhancing indentation and impact resistance in auxetic composite materials. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 198, 108229 (2020).

Xi, H., Xu, J., Cen, S. & Huang, S. Energy absorption characteristics of a novel asymmetric and rotatable re-entrant honeycomb structure. Acta Mech. Solid Sin. 34 (4), 550–560 (2021).

Kim, H. & Lee, S. Characterization of electrical heating of Graphene/PLA honeycomb structure composite manufactured by CFDM 3D printer. Fash Text. 7, 8 (2020).

Kim, H. & Lee, S. Electrical heating performance of graphene/PLA-based various types of auxetic patterns and its composite cotton fabric manufactured by CFDM 3D printer. Polymers 13 (12), 2010 (2021).

Choi, H. Y., Shin, E. J. & Lee, S. H. Design and evaluation of 3D-printed auxetic structures coated by CWPU/graphene as strain sensor. Sci. Rep. 12, 7780 (2022).

Choi, H. Y., Shin, E. J. & Lee, S. Piezo-resistive sensor of auxetic structures based on 3D-Printed TPU coated by Castor-oil-Based waterborne Polyurethane/Graphene. Fibers Polym. 24, 15–28 (2023).

Jung, I., Kim, H. & Lee, S. Charaterizations of 3D printed re-entrant pattern/aramid knit composite prepared by various tilting angles. Fash Text. 8, 44 (2021).

Jung, I. & Lee, S. Shape recovery properties of 3D printed re-entrant strip using shape memory thermoplastic polyurethane filaments with various temperature conditions. Fash Text. 10, 27 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Efficacy of auxetic lattice structured shoe sole in advancing footwear comfort—From the perspective of plantar pressure and contact area. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1412518 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Pressure-Reducing design of 3D-Printed diabetic shoe midsole utilizing auxetic lattice structure. Appl. Sci. 14 (12), 5291 (2024).

Kim, E. & Kim, S. Development of smart insole for cycle time measurement in sewing process. Fash Text. 8, 3 (2021).

Zuniga, J. et al. Development of 3D-printed orthopedic insoles for patients with diabetes and evaluation with electronic pressure sensors. Designs 6 (5), 95 (2022).

Orsu, B. & Shaik, Y. P. Compression strength analysis of customized shoe insole with different infill patterns using 3D printing. OALib 9, e8712 (2022).

Peker, A. et al. Additive manufacturing and Biomechanical validation of a patient-specific diabetic insole. Polym. Adv. Technol. 31 (5), 988–996 (2020).

Tan, X. et al. Bioinspired flexible and programmable negative stiffness mechanical metamaterials. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5 (6), 2200400 (2023).

Chen, X. & Lee, S. Physical property of 3D-printed N-pointed star-shaped outsole prepared by FDM 3D printer using the lightweight TPU. Polymers 14 (15), 3189 (2022).

Zolfagharian, A., Lakhi, M., Ranjbar, S. & Bodaghi, M. Custom shoe sole design and modeling toward 3D printing. Int. J. Bioprint. 7 (4), 396 (2021).

Binelli, M. R. et al. Digital manufacturing of personalised footwear with embedded sensors. Sci. Rep. 13, 1962 (2023).

Rodriguez-Parada, L., de la Rosa, S. & Mayuet, P. F. Influence of 3D-printed TPU properties for the design of elastic products. Polymers 13 (15), 2519 (2021).

Ursini, C. & Collini, L. FDM layering deposition effects on mechanical response of TPU lattice structures. Materials 14 (19), 5645 (2021).

Shanmugam, V. et al. Fatigue behaviour of FDM-3D printed polymers, polymeric composites and architected cellular materials. Int. J. Fatigue. 143, 106007 (2021).

Fekete, I., Ronkay, F. & Lendvai, L. Highly toughened blends of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and natural rubber (NR) for FDM-based 3D printing applications: the effect of composition and infill pattern. Polym. Test. 99, 107205 (2021).

Lee, S. K., Kim, Y. R., Kim, S. H. & Kim, J. H. Investigation of the internal stress relaxation in FDM 3D printing: annealing conditions. J. Korean Soc. Manuf. Process. Eng. 17 (4), 130–136 (2018).

Thrimurthulu, K., Pandey, P. M. & Reddy, N. V. Optimum part deposition orientation in fused deposition modeling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 44 (6), 585–594 (2004).

Chacón, J. M., Caminero, M. A., García-Plaza, E. & Núñez, P. J. Additive manufacturing of PLA structures using fused deposition modelling: effect of process parameters on mechanical properties and their optimal selection. Mater. Des. 124, 143–157 (2017).

Scapin, M. & Peroni, L. Numerical simulations of components produced by fused deposition 3D printing. Materials 14, 4625 (2021).

Jung, I., Shin, E. J. & Lee, S. Study on CNT/TPU cube under the 3D printing conditions of infill patterns and density. Sci. Rep. 13, 17728 (2023).

Jung, I. & Lee, S. Three-dimensional printed re-entrant strain sensor using various carbon types/thermoplastic polyurethane filaments. Text. Res. J. 94 (5–6), 658–670 (2024).

Jung, I. & Lee, S. Electro-mechanical property of 3D printed cubic structure using carbon Materials/Thermoplastic polyurethane filament with various infill patterns. Fiber Polym. 26, 1717–1728 (2025).

Pibulchinda, P., Barocio, E., Favaloro, A. J., Pipes, R. & Byron Influence of printing conditions on the extrudate shape and fiber orientation in extrusion deposition additive manufacturing. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 261, 110793 (2023).

Keles, O., Blevins, C. W. & Bowman, K. J. Effect of build orientation on the mechanical reliability of 3D printed ABS. Rapid Prototyp. J. 23 (2), 320–328 (2017).

Beloshenko, V. et al. Mechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane-based three-dimensional-printed lattice structures: role of build orientation, loading direction, and filler. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 10 (2), 245–255 (2023).

Mencarelli, M., Sisella, M., Puggelli, L., Innocenti, B. & Volpe, Y. Sensitivity analysis of 3D printing parameters on mechanical properties of fused deposition Modeling-Printed polylactic acid parts. Appl. Mech. 6 (1), 17 (2025).

Sánchez, C., Rodríguez, D., Otero, S. & Monje, C. A. Enhancing sensing performance of 3D-printed TPU/CB piezoresistive strain sensors through integration of silver ink IDE. Sens. Actuators Phys. 393, 116757 (2025).

Kim, E., Khaleghian, S. & Emami, A. Behavior of 3D printed stretchable structured sensors. Electronics 12 (1), 18 (2023).

Hohimer, C. J., Petrossian, G., Ameli, A., Mo, C. & Pötschke P. 3D printed conductive thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube composites for capacitive and piezoresistive sensing in soft pneumatic actuators. Addit. Manuf. 34, 101281 (2020).

Hochman, L. Thingivers. https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2897250 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant (No. NFR-2021R1A4A1022059) of the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea. And This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT)(No. RS-2023-00272281).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. conceived the work; I.J. prepared the samples and performed the experiments. I.J and S.L are participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, I., Lee, S. Characterization of 3D printed re-entrant midsole structure with various infill density and print direction. Sci Rep 15, 43719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27421-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27421-y