Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that people focus on fewer specific features of natural environments compared to built environments. This may imply that neural activity stronger converge across individuals in green environments than in built environments, where people may focus very differently on diverse and often overloading urban stimulation. We hypothesized that the similarity of mental states across individuals should increase during exposure to green environments compared to built environments. Thus, we conducted an electroencephalography study in which we measured the correlation of neural responses among 30 participants using the inter-subject correlation (ISC). Using the ISC method, we calculated the similarity of the brain activity of a group of people as they were exposed to videos of 5-minute walks through parks, boulevards, or busy roads. The behavioral results showed that on average, participants rated the videos of parks as 39 and 65% more relaxing than boulevards and busy roads, correspondingly. Our electrophysiological results showed that the average similarity in brain activity, as measured by ISCs, was significantly stronger during the observation of parks compared to boulevards and busy roads. On average, ISCs for parks were 26 and 40% higher compared to boulevards and busy roads, respectively. We also found that parks increase the similarity of brain activity, particularly in the delta band, which reflects the most evolutionary old and phylogenetically preserved cortical activity. Our results further confirm that during urban walks in busy boulevards and highways, people’s attention is distracted, as indicated by weaker brain synchronization between individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban dwellers face highly diverse environments daily, ranging from noisy built districts to calm and comfortable green zones. Almost 40 years ago, Edward Wilson1 proposed the influential biophilia theory, which posited that evolution developed the strong tendency of humans to focus on and affiliate with natural environments. In a similar line of reasoning, attention restoration theory suggests that if human cognitive functions have evolved in natural environments, people today could be overwhelmed with artificial urban stimuli2. Urbanized built environments demand a constant concentration of attention and top-down cognitive resources, leading to cognitive overload. Accordingly, natural stimuli, such as urban trees, moderately load involuntary attention and therefore restore cognitive resources. Similarly, psycho-evolutionary theory3 emphasizes that built environments lead to physiological and cognitive depletion when compared to natural environments3,4. Contrary to attention restoration theory, this theory suggests that an initial affective response to natural environments underlines the restoration of cognitive resources. Recently conditioned restoration theory proposed that the effects of natural environments are based on conditioning and associative learning: after associating nature with relaxation, subsequent exposures to nature trigger relaxation due to previous conditioning5. An alternative perceptual fluency model emphasizes the role of sensory features of nature and suggests that natural environments are processed more fluently due to their low-level sensory features6,7. Such perceptual fluency lessens cognitive processing of natural stimuli, which explains the restorative effects of nature. Overall, attention restoration theory emphasizes the restorative role of soft fascination or tranquility—environmental visual characteristics that capture involuntary attention modestly and simultaneously elicit pleasant experiences. Psycho-evolutionary theory highlights the restorative role of affective responses to natural environments. Conditioned restoration theory stresses the positive effect of relaxation associated with nature, while perceptual fluency model emphasizes the role of the less costly cognitive processing of natural stimuli. In this study, we investigated neural responses to natural and built urban environments to further explore the assumptions of these key theories in the field of urban greening.

Berto and colleagues8 demonstrated that eye movements related to photographs of natural environments are characterized by lower exploration and a smaller number of fixations compared to built environments. The results suggest that people focus on fewer specific features of natural scenes compared to built scenes. Follow-up studies convincingly showed that when viewing nature scenes, the participants made less but longer eye fixations relative to environments with low restorative potential9,10. These results may reflect a lower cognitive effort and a different cognitive strategy during the visual processing of natural scenes compared to built urban scenes. They also support attention restoration theory by confirming that less cognitive effort is required to view a green urban environment. In the current study, we aimed to test the differential processing of green and built urban environments using electroencephalography (EEG).

Roger S. Ulrich11 exposed participants to images of nature or urban environments and found that alpha EEG oscillations were significantly higher during vegetation slides compared to urban slides, and when subjects viewed water rather than urban content. EEG studies have since suggested that natural environments reliably increase the power of alpha oscillations in the EEG11,12,13,14, and favor stress reduction and attention restoration13,15,16. However, previous EEG studies have primarily focused on alpha band oscillations, which have been associated with the inhibition of neuronal activity17,18,19, playing a role in gating information flow20,21. Importantly, both attention restoration and psycho-evolutionary theories emphasize the restorative role of involuntary attention and affective responses to green environments rather than the role of the inhibition of neuronal and cognitive activity. Of significance in this context are ecologically valid studies of involuntary attention and affective responses to natural environments that consider new, complex experimental paradigms and neuroimaging tools.

The sensory processing of urban environments has mainly been investigated using static images, despite the fact that our real-life urban experience is much closer to a continuous, dynamic movie than to a still photo. To study the relationship between dynamic urban stimuli and brain activity, we measured the synchronization of neural responses among a group of participants using inter-subject correlation (ISC) analysis. In brief, ISC analysis measures the similarity of brain activity among a group of people as they respond to the same dynamic stimulus, for example, a movie, audiobook, music, or a video of urban scenes22,23. Strong engagement with the dynamic stimulus results in high neural responses that are highly correlated across all participants, while a lack of engagement manifests in generally lower neural responses that correlate less across participants. Thus, ISC objectively indexes the magnitude of selective attentional engagement24 and can be used as a novel tool to investigate human attention to various urban environments.

Previous EEG studies have demonstrated that ISC reflects audience’s engagement with naturalistic stimuli, such as narrative cohesion24,25, large-scale population preferences26, attentional state25,27, and video viewership28. Importantly, when attention is diverted away from a stimulus, the ISC across participants decreases, while the allocation of attention to the stimulus increases the ISCs25,27. Therefore, the EEG-ISC can be interpreted as an index of audience engagement, described by Dmochowski and colleagues24 as “emotionally laden attention”.

For the first time, to our knowledge, we applied ISC analysis to assess psychological and brain states in green and built environments. More precisely, we used ISC analysis to study the brain-to-brain similarity of brain activity in response to videos of green areas (parks), streets with rows of trees (boulevards), and built districts with busy roads (highways). As mentioned earlier, previous studies have shown that people focus on fewer specific features in green environments compared to built environments8,9,10, suggesting that green scenes should evoke more similar brain activity (higher ISC) of a group of people than built urban scenes. By contrast, busy built environments constantly distract attention due to their numerous salient features, resulting in highly dissimilar brain activity across individuals. Thus, a higher ISC in green areas than in urban areas may further support the view that less neurocognitive effort is required to view green urban scenes than built urban scenes. Alternatively, someone might suggest that focusing on fewer features in green environments could indicate mind wandering29, which could result in a very different brain activity of people, depending on what the person starts thinking about. For example, Kathryn Williams and colleagues30 suggested that if no response is required, attention may become inwardly focused leading to mind wandering in natural environments. Our study aims to clarify these conflicting views by carefully analyzing ISCs.

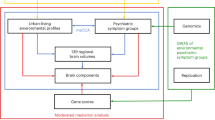

To test this hypothesis, we recorded the EEG of 30 participants while they watched the videos of a 5-minute walk through parks, boulevards, or busy highways (Fig. 1). If natural environments trigger more focused visual exploration and stronger emotional engagement than built environments, green parks should evoke higher ISC and, thus, more similar brain activity among a group of people compared to urban scenes in boulevards or highways.

Results

Behavioral results

Preferences for urban environments: The questionnaires revealed that participants preferred green and quiet urban environments. Specifically, participants indicated the importance of green spaces (mean rating = 6.6 out of 7), the quiet pace of urban life (mean rating = 4.6 out of 7), the moderate level of noise (mean rating = 5.5 out of 7), and the moderate importance of road conditions (mean rating = 4.1 out of 7).

The participants rated the videos of urban environments differently (see Fig. 2). The one-way Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance showed significant differences in perceived environmental risks (“Does this environment threaten the health of residents?”) for six videos (p < 0.0001, effect size η² = 0.521). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that highways were perceived as associated with significantly higher environmental risks than boulevards (p < 0.0001, with large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.579 to 0.630), 95% CI ranging from [2.00, 2.50] to [3.50, 4.00]) and parks (p < 0.0001, with large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.733 to 0.786), 95% CI ranging from [3.50, 4.00] to [4.50, 5.50]). Similarly, boulevards were perceived as associated with significantly higher environmental risks than parks (p < 0.001, with moderate to large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.479 to 0.653), 95% CI ranging from [1.00, 1.50] to [2.00, 3.00]). Overall, participants rated parks as the least environmentally risky environment. The Kruskal–Wallis analysis also indicated a significant difference in the perceived level of urban boredom (“Is this environment boring?”) for the six videos (p < 0.0001, η² = 0.227, large effect size). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that highways were rated as significantly more boring than parks (p < 0.05, with moderate effect sizes (r ranging from 0.318 to 0.471), 95% CI ranging from [0.50, 1.00] to [2.50, 3.00]) and boulevards (p < 0.001, with large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.517 to 0.665), 95% CI ranging from [1.50, 2.00] to [3.00, 3.50]). Despite the abundance of visual events and noise, highways were perceived as the most boring urban environments. Finally, we found a significant difference in the perceived restorative potential of urban environments (“Is it difficult to relax in this environment?”, Kruskal–Wallis analysis, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.464, large effect size). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that highways were rated as significantly less relaxing than boulevards (p < 0.01, with moderate to large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.443 to 0.654), 95% CI ranging from [1.00, 3.00] to [3.00, 4.00]) and parks (p < 0.001, with large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.640 to 0.751), 95% CI ranging from [2.50, 4.00] to [4.50, 5.00]). Further, parks were rated as significantly more relaxing than boulevards (p < 0.01, with moderate to large effect sizes (r ranging from 0.455 to 0.632), 95% CI ranging from [1.00, 1.50] to [2.00, 2.50]). Thus, on average, participants rated the videos of parks as 39 and 65% more relaxing than boulevards and busy roads, correspondingly. The findings indicated that urban environments that feature green spaces and a quiet pace of life were preferred by the participants. Moreover, parks were found to be the most relaxing and least environmentally risky environment, whereas highways were perceived as the least relaxing and most environmentally risky.

Mean ratings evaluating the environmental quality of six urban environments (videos). The results of 7-point Likert scale questions represent (A) perceived environmental risks, (B) the level of stimulation, and (C) difficulties in relaxation for highways, boulevards, and parks. Note. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) within each condition. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

EEG results: shared brain responses to urban environments

To test our hypothesis, we statistically compared the similarity of brain activity, measured as ISC scores, in the group of participants during exposure to videos of a 5-minute walk through parks, boulevards, or highways. We calculated one aggregate ISC-score for each video (for details, see the “Methods” section). A one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of the factor environment (Highway 1, Highway 2, Park 1, Park 2, Boulevard 1, and Boulevard 2) on brain activity synchronization across participants: F(5, 145) = 8.73, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.174. Post-hoc analyses revealed that ISC scores for two parks were significantly larger than ISC scores for other urban environments with a medium to large effect size: Park 1 vs. Highway 1 (p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = -1.09, 95% CI [-1.54, -0.63]); Park 1 vs. Highway 2 (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = -0.69, 95% CI [-1.08, -0.28]); Park 1 vs. Boulevard 1 (p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = -0.80, 95% CI [-1.21, -0.38]); Park 2 vs. Highway 1 (p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = -1.04, 95% CI [-1.48, -0.59]); Park 2 vs. Highway 2 (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = -0.69, 95% CI [-1.08, -0.29]). Other post hoc tests showed no significant differences between ISC scores (see Fig. 3). Thus, participants demonstrated higher brain-to-brain synchrony in response to parks than to boulevards or highways. On average, ISCs for parks were 26 and 40% higher compared to boulevards and\ highways, correspondingly.

Manipulation check: analysis of control videos

Previous studies have shown that engaging action movies evoke strong brain activity synchronization across participants, while open scenes of the sea evoke low brain activity synchronization24. In this study, we used Control 1 (an action movie) and Control 2 (a scene of a seaside) videos to verify the effect of attentional engagement on brain activity synchronization across participants. Supplementary Figure S2 shows that videos Control 1 and Control 2, as expected, evoked the highest and lowest ISC scores, respectively. This trend was supported by a one-way repeated measures ANOVA, which showed the significant effect of the factor environment (Highway 1, Highway 2, Park 1, Park 2, Boulevard 1, Boulevard 2, Control 1, Control 2): F(2, 57.89) = 727.08, p < 0.0001, η² = 0.952. Post-hoc pairwise analyses revealed that the similarity of brain activity across participants for the Control 1 video was significantly higher than for the other seven videos (p < 0.0001). By contrast, the similarity of the brain activity across participants for the Control 2 video was significantly lower than for Park 1 (p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = -1.16, 95% CI [-1.61, -0.69]), Park 2 (p = 0.01, Cohen’s d = -0.88, 95% CI [-1.29, -0.45]), and Control 1 video (action movie).

Average inter-subject neural synchronization for different urban environments (videos), as measured by ISCs. Overall, the participants demonstrated a higher similarity of brain activity in response to parks than to busy boulevards or highways. Note. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) within each condition. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Dynamic shared brain responses in different urban environments

To identify the specific urban events that induced the strongest peaks of brain-to-brain synchrony, we calculated the changes in the ISC score over the course of the videos for the strongest correlated components (see Fig. 4, where the gray line represents the significance threshold). We used a 1-second window with an 80% overlap that allowed us to capture dynamic changes in brain-to-brain synchrony. To identify ISC peaks we utilized a significance threshold, established using 1000 phase-randomized permutations (for details, see the “Methods” section).

Interestingly, in the point-by-time point ISC analysis, different event types triggered peaks in brain-to-brain synchrony when the participants watched videos of different urban environments. For example, during the Park 1 video, a flowerbed and passers-by evoked the strongest peaks of ISC scores (Fig. 4A). During the crowded Boulevard 1 video, the strongest ISC peaks were induced by a running child and a moving cyclist. However, during videos of the Highway 1, peaks were triggered by an approaching car and a significant change of view. For details of different events that triggered peaks in brain-to-brain synchrony, see Supplementary Table S4. Overall, during the videos of parks, the participants’ attention was guided by urban stimuli associated with soft fascination, while safety-related urban stimuli guided their attention while watching videos of boulevards, particularly during videos of highways.

The strongest peaks of inter-subject neural synchronization (right) and topographic maps of the mean ISCs (left) for three urban environments (videos). For the Park 1 video, the strongest ISC peaks were triggered by an attractive flower bed and rare passersby, while for Boulevard 1 and Highway 1, the peaks occurred during observations of a running child and a quickly approaching car, respectively. The photos illustrate scenes that coincide with the strongest local peaks of the ISC scores. Note. The dynamic ISC and topo-plots are represented by the first maximally correlated Component 1 only. The gray color indicates the time-varying statistical significance threshold that represents the 95th percentile of permutations.

Neural synchronization in different frequency bands

Since different EEG frequency bands represent different cognitive and physiological states, we reanalyzed the ISC separately for four frequency bands of interest (delta: 0.5–4 Hz, theta: 4–8 Hz, alpha: 8–12 Hz, beta: 12–25 Hz). Figure 5 shows that the differences in overall ISC scores between urban environments were driven mainly by differences in the delta range. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed the strong significant effect of the factor environment (Highway 1, Highway 2, Park 1, Park 2, Boulevard 1, and Boulevard 2) on brain activity in the delta frequency band (F(5,145) = 10.63, p < 0.0001) and the weaker effect in the theta frequency band (F(5,145) = 2.58, p < 0.05).

In the delta band, post-hoc analyses revealed that ISC scores for two parks were significantly larger than ISC scores for other urban environments: Park 1 vs. Highway 1 (p < 0.0001); Park 1 vs. Highway 2 (p < 0.01); Park 1 vs. Boulevard 1 (p < 0.01); Park 1 vs. Boulevard 2 (p < 0.05); Park 2 vs. Highway 1 (p < 0.0001); Park 2 vs. Highway 2 (p < 0.01); Park 2 vs. Boulevard 1 (p < 0.01); Park 2 vs. Boulevard 2 (p < 0.01). In the theta band, post-hoc analyses revealed that only ISC scores for Boulevard 2 were significantly larger than ISC scores for Boulevard 1 (p < 0.01).

Thus, we observed the strongest brain synchronization between individuals in the delta range for parks, which has been suggested to reflect the most evolutionary ancient and phylogenetically preserved cortical circuits particularly involved in basic motivation and reward31.

Discussion

During the EEG recording, the participants in this study were shown videos of boulevards, parks, and highways, and their brain synchronization was measured using ISC, which is a neural index of audience engagement. Our results showed that parks elicited stronger brain synchronization between individuals compared to highways and boulevards. Detailed EEG analysis revealed that parks strongly attracted the participants’ attention to a limited number of pleasant visual events, which led to relatively similar neurocognitive processing of urban elements, resulting in stronger brain synchronization between individuals. By contrast, videos of urban walks in boulevards and highways drew attention to numerous safety-related distractive urban events, leading to weaker brain synchronization between individuals due to the varying cognitive processing of urban elements.

The ISC approach has been developed to study how the brain deals with the complexity and dynamics of naturalistic sensory streams, such as movies, audiobooks, or music23,32. Previous studies have shown that ISC is strongly influenced by attentional engagement24,25,27. If attention is diverted away from a sensory stream, ISC is smaller25,27, while attentional engagement increases ISC. For example, ISC is larger when attending to audiovisual narratives than when attention is directed inward to a mental arithmetic task25. Further, a significant reduction in ISC occurs even upon a second viewing of the same video, which makes it less engaging24. Overall, previous studies suggest that ISCs, as maximally correlated components of neural activity, reflect attention- and emotion-modulated cortical processing. Thus, our findings that parks evoke higher ISCs in a group of people than built urban scenes indicate that green urban areas strongly engage people in the cognitive processing of emotionally positive events that required less neurocognitive effort than built urban scenes. Importantly, the participants in our study also rated parks as the most restorative environment.

Our finding of a particularly large brain-to-brain synchrony when participants were exposed to videos of parks is in line with previous eye-tracking studies. Eye movements reflect visual attention and determine where people focus on33. For instance, Martínez-Soto and colleagues found that eye movements during the observation of photos with higher restorative potential were characterized by fewer fixations than those of photos with lower restorative potential34. Thus, green restorative environments are associated with reduced eye movement activity, which reflects low cognitive effort in processing natural scenes. Many eye-tracking studies have shown that eye movements during the processing of photographs of natural environments are characterized by lower exploration and a smaller number of fixations compared to those rated low on fascination urban environments8,9,10,34,35. Thus, eye-racking studies reflect different cognitive strategies during the processing of natural and built scenes. Our EEG and behavioral results, combined with previous eye-tracking studies, further support the idea that built urban environments overload attention compared to green environments, while the latter may effectively restore the cognitive resources of human brains.

Many studies of the visual processing of urban environments have been based on attention restoration theory36, which emphasizes the negative impact of effortful focused attention on cognitive functions in urban settings. According to Kaplan and Kaplan36, voluntary attention, which requires significant effort, induces cognitive fatigue. By contrast, a form of involuntary attention, known as fascination, is based on a genuine interest in visual details that require little cognitive effort. Fascinating natural scenes allow the depleted attentional system to rest. Previous eye-tracking studies have indicated that a lower number of fixations on natural scenes signifies a lack of distractions. Our results further support this view, demonstrating that different people display more similar brain activity/mental states in parks than in busy boulevards and highways, where various urban events can distract people and make brain activity highly dissimilar across individuals. Our ISCs data show that during urban walks, the green environment tunes attention to rare salient events, such as beautiful details of nature, which helps people focus on emotionally positive, highly fascinating urban episodes. Our results further reveal that for parks, the strongest shared brain responses were evoked by an attractive flower bed, while for crowded boulevards and highways, the strongest peaks of shared brain responses were triggered by a moving cyclist or an approaching car.

Our in-depth ISC analysis also supports psycho-evolutionary theory3, which emphasizes the key role of an “initial affective response” to natural environments in the restoration of cognitive resources. We found that stronger inter-subject synchronization in parks was underlined by EEG activity in the low-frequency delta band. Interestingly, delta waves have been implicated in the integration of brain activity with homeostatic processes31. Previous studies have shown that overnight delta activity negatively correlates with arterial pressure37 and cortisol levels38. Furthermore, EEG delta activity correlates positively with basal metabolic rate over the human lifespan39. Overall, low-frequency EEG is a reliable feature of reduced alertness31,40, which has been used in an EEG-based sedation index41,42.

Some studies have indicated a link between delta oscillations and attention processes43,44,45,46, as well as the processing of emotional stimuli47 and the detection of motivationally salient stimuli in the environment48,49. Importantly, delta EEG activity generation has been linked to the activity of the ventral tegmental area, the nucleus accumbens, and the medial prefrontal cortex, which are key regions of the brain reward system31. For example, Zen meditators showed stronger delta activity in the medial prefrontal cortex during rest compared to controls, which may indicate inhibition of the prefrontal cortex, resulting in reduced cognitive engagement50. Furthermore, delta activity can inhibit or amplify sensory input and play a role in efficiently encoding stimuli51,52.

To summarize, our results support both attention restoration theory, which emphasizes the role of natural environments in the restoration of cognitive resources, and psycho-evolutionary theory, which focuses on the “initial affective response” to natural environments. Stronger shared brain responses to parks than to built environments highlight the role of the soft, fascinating cognitive characteristics of parks that capture involuntary attention and do not overload cognitive systems. However, the strong shared delta activity evoked by parks also supports the role of affective responses to natural environments in the restoration of cognitive resources. It is worth mentioning that our results also do not contradict conditioned restoration theory, which links natural environments with the associative learning-related relaxation and perceptual fluency hypothesis that emphasizes the less costly cognitive processing of natural stimuli. Our results are further in line with the recent literature that links natural exposure and enhanced inhibitory control6,7. Nature-related reductions in cognitive efforts are manifested in inhibitory efficiency, which is performance-related and a well-established indicator of cognitive effort53,54.

Previous EEG studies that investigated the effects of the environment on brain activity have mainly used traditional data analysis methods, focusing on the alpha (8–13 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) frequency bands11,12,55. However, the current study used the ISC signal to capture shared brain responses, which reflect different brain activity than more traditional EEG analyses. Hasson and colleagues developed a revolutionary ISC technique that compared neural responses across individuals instead of within individuals22. The ISC technique calculates the correlation across participants’ brain signals to estimate the reliability of brain responses between participants. Unlike traditional approaches, the ISC technique can be applied to continuous, dynamic natural stimuli, such as video, music, or speech, without the need for specific event markers23. The ISC method specifically identifies the stimulus-driven brain activity shared by the majority of participants. Thus, this method compares neural responses across participants, assuming that when a group of individuals attends to the same dynamic stimulus, a portion of the induced neural activity is synchronized across participants, indicative of a similar reaction to the external world or of an increase in the attention directed to a stimulus rather than an internal state25,56. Notably, our results show that a large proportion of the participants shared delta waves, measured by EEG and ISC, when they viewed videos of urban walks through parks. Importantly, our findings do not contradict previous studies indicating that natural environments reliably increase the power of alpha oscillations in the EEG11,12,13,14 : since such stronger alpha oscillations in natural environments are not necessarily correlated between participants an inter-subject synchronization of alpha EEG activity (ISCs) could be very minimal.

Our results further suggest that highways and boulevards dramatically disrupt people’s engagement in urban environments. In particular, cars, cyclists, and pedestrians dissipate attention during urban walks. Our findings can be important for landscape planning to maximize attention restoration. Landscape architects may make an extra effort to isolate roads from green areas, using dense planting, to reduce the density of pedestrians and to further separate cycling and walking routes. Nowadays, an evidence-based approach to landscape planning is essential to supporting or challenging popular trends in landscape architecture. We further show that salient urban elements that attract attention are not necessarily beneficial for health or attention restoration. Importantly, such an evidence-based approach to landscape planning is also more persuasive for policymakers and decision makers at the city and municipal levels. Our results are in line with the previous studies that examined the impact of greenery on urban stress4,57,58,59. Importantly, Cao and colleagues59 explored the recovery effects of various types of greenway environments and demonstrated a superior psychophysiological recovery potential of urban park-type greenways. Altogether, it suggests that urban greenways should not only connect urban communities, but also provide spaces for relaxation, physical and mental health restoration. Overall, our findings further advocate for environmental changes to increase access to parks. The results further suggest that urban planners should prioritize green spaces, particularly quiet areas, to improve urban environments.

Study limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of the study. First, we used videos of real urban walks, making it difficult to control all aspects of the urban scenes, including the number of passers-by in each frame. Future studies should control for the number of people (faces) in the videos and for the complexity of the visual scenes, as this can modulate participants’ attention. Second, we normalized the sounds of the videos, largely ignoring the cognitive effect of urban noise. The effect of acoustic noise on the sensory processing of urban spaces should be investigated in more detail in follow-up studies. Additionally, the videos lack some important sensory features of urban space, such as urban smells, kinesthetic sense of movement, and location. To avoid moment artifacts, we also instructed the participants to avoid movements that may affect brain activity and behavior. Furthermore, the ISCs technique requires perfect synchronization of stimuli across participants, which limits experimental paradigms. In our study, the participant viewed eight videos that potentially can induce some learning, fatigue, or carry-over effects. Importantly, this type of experimental design is typical in the field and it is usually addressed by similar randomization procedures60,61,62. Nevertheless, future studies could consider shorter or between-subject paradigms to better control for extraneous experimental variables which can potentially affect the sensitivity of the statistical analysis. Future studies should also focus on the role of other sensory modalities in the sensory processing of urban spaces, examine spatial/temporal frequencies of the visual flow in various urban environments and account for the duration of urban walks and the individual or cultural differences of participants.

Conclusion

Our neurourbanism study demonstrated that the average similarity across the brain activity of 30 participants was particularly strong during the observation of parks compared to the observation of highways and boulevards. Such stronger inter-subject brain synchronization measured by ISCs indicates an increasing similarity of mental states across individuals in green urban spaces. Our results suggest that parks do not distract people’s attention, as they expose visitors to a limited number of visual events requiring low cognitive effort. We show that parks increase inter-subject synchronization of EEG activity, particularly in the delta band, reflecting the most evolutionary old and phylogenetically preserved cortical activity involved in basic motivation and reward31. Overall, our results suggest that cognitive and neural processing of parks converge across individuals stronger than processing of highways and boulevards, which leads to stronger brain synchronization between individuals. On the contrary, during urban walks on boulevards and highways, people’s attention is distracted, which leads to weaker brain synchronization between individuals.

Methods

Participants

Thirty participants (20 females), aged 19–47 (mean = 28.5, standard deviation = 7.5), with normal vision and hearing, right-handed, and without neurological conditions and/or disorders participated in the study. All participants signed an informed consent form to participate in the study and were compensated for their time. The study was approved by the university ethics committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval and informed consent were waiver by HSE university ethical committee. The participants were informed in detail of the purpose and nature of the study and signed their informed consent for study participation and publication of identifying information/images. The sample size was calculated based on the guidelines for ISC research. An EEG study assessed the reliability of ISC and demonstrated that to achieve a minimally acceptable reliability, a sample size of n = 15 is required63. Furthermore, the dynamic pattern of a video can be reliably tracked using a sample size of n = 27. Furthermore, Kauppi and colleagues64 demonstrated that ISC analysis can be conducted with as few as 12 participants. Taking into account the explorative nature of the study, the sample size was larger than in previous studies exploring ISCs with similar setups24,26. The participants were recruited via social media.

Stimuli and questionnaires

During the EEG recording, participants were exposed to eight videos, with each video lasting five minutes (Fig. 1). Six of these videos depicted urban environments, and two control videos (see below for details) were included. The loudness of all videos was normalized. The order of videos shown were randomized across participants with an interstimulus interval of 60–120 s. After the first four videos, a 5-minute break was given.

To create the six videos of urban environments, we filmed 5-minute walks through a highway, boulevard, and city park in two different cities (see supplementary materials for video files) with a professional camera (for details, see Supplementary Figures S1.1–S1.6). Supplementary Tables S1-S2 summarize the features of videos (for details of the similar approach, see65. The highways (Highway 1 and Highway 2) were represented by urban areas with car traffic and limited greenery. The parks (Park 1 and Park 2) were filmed in green areas with no buildings or paved roads, while the videos of boulevards (Boulevard 1 and Boulevard 2) were recorded in green urban areas with buildings, limited transport, and people walking. Supplementary Figures S1.1–S1.8 illustrate all the videos used in the current study. All videos were recorded by the same cameraman during the daytime (July, 2020) in two million cities separated by a distance of 700 km. In each city video-recordings of the highway, boulevard, and city park were conducted on the same day. While selecting highways, boulevards, and city parks in two different cities, we searched for urban areas with similar types of vegetation, land use/purpose, socio demographics.

Two control videos were included: Control 1 video depicted a scene from the movie “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” (1966), while Control 2 video showed an open scene of a seaside (for details, see Supplementary Figures S1.7–S1.8). Importantly, previous studies have shown that such control videos either evoke very high (Control 1 video showing the action movie) or extremely low (Control 2 video showing the empty seaside) ISC scores (e.g.,24). We used ISCs for the control videos as reference points for the descriptive analysis of ISCs for urban environments. We assumed, as a sanity check, that among eight videos, the control video (Control 1) should evoke the highest ISC scores, while the control video (Control 2) should evoke the lowest ISC scores (see Supplementary Figure S2).

During the study, the participants were instructed to watch the videos attentively and to avoid movements. The study was programmed using NBS Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.). The videos were presented on an HD monitor (1920 × 1080 resolution), and light detection photodiode (detecting onsets of videos) controlled the synchronization of videos and EEG recording. The EEG study lasted approximately 60 min. Since the ISC method requires the identical sensory stimulation of all participants we used the standard video stimuli instead of 360-degree virtual reality videos that allow the user to change the view as desired.

At the end of the study, the participants rated the urban environments (videos) presented during the EEG recordings, reported their preferences regarding urban environments, and answered socio-demographic questions. The participants rated each video on a 7-point scale: 1 — fully agree, 7 — fully disagree. The list of all questions is available in Supplementary Table S3. Not all questions were used in the current study, as a large set of questions was collected for another project. For this study, we analyzed the questions screening participants’ evaluations of videos: how relaxing, boring, familiar and healthy the urban environments were perceived (It is impossible to relax in this environment; This environment is very boring; Does this environment threaten the health of residents; How familiar is this environment to you? Have you been there before? ). We also screened participants’ preferences for different parameters of urban spaces (the presence of green areas; a quiet environment; fast-paced, active life) using a 7-point scale (1 — not important at all, 7 — very important).

EEG recording

The EEG was recorded using the actiCHamp system (BrainProducts) at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz. We used a standard 64-electrode cap according to the extended 10/20 international system. Reference electrodes Tp9 and Tp10 were placed on the left and right mastoids, respectively. The ground electrode was placed at Fpz. To remove eye movement artifacts, an electrooculogram (EOG) was also recorded with two auxiliary electrodes. The impedance level was kept below 15 kΩ. The EEG recordings were conducted in a soundproof, lightproof and electrically shielded room during the daytime.

EEG preprocessing

First, the EEG signal was visually inspected to exclude datasets (or EEG channels) with clear artifacts. For each participant, the noisy EEG channels were manually set to zero but were not excluded from the dataset to preserve the temporal structure of the datasets and perform further cross-covariance calculations correctly. Signal processing and data analysis were performed offline using MATLAB software (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). Second, EEG and EOG data were high-pass filtered (0.5 Hz cutoff), and notch-filtered at 50 Hz. Eye movement artifacts were removed by linearly regressing the signals in the EOG channels from the signals in the EEG channels. Lastly, since ISC is sensitive to outliers, EEG data points above three standard deviations of the mean in each electrode were set to zero. For the additional analysis, the EEG signal was then filtered into four frequency bands (cut-off frequencies: delta: 0.5–4 Hz, theta: 4–8 Hz, alpha: 8–12 Hz, beta: 12–25 Hz).

Inter-subject correlation (ISC) analyses

ISC is a measure of the similarity in neural activity between pairs of individuals that reflects the extent to which their brain responses are synchronized during shared tasks. To calculate the ISC for each video clip, we implemented a correlated component analysis— CorrCA24. This approach assumes that participants who are engaged with video content exhibit neurocognitive responses that are correlated among each other23. By contrast, a lack of engagement with video content leads to weak and highly variable neurocognitive responses that are not correlated across participants23. Below we explain the ISC analysis in more detail.

Aggregate ISC scores. CorrCA identifies linear combinations of EEG electrodes that have a similar time course in all participants (for details, see25,60. Each such linear combination is a correlated component. To compute the ISC for each video clip, we summed the three strongest correlated components, following previous studies24,25. This was performed using a leave-one-out approach, resulting in a single ISC value per video and participant, reflecting the synchronization level between this participant and the rest of the group, while watching this video24,60.

In more details, CorrCA extracts data projections with maximal correlation24. The pooled between-subject cross-covariance and pooled within-subject covariance were calculated as described below. Between-subject cross-covariance was computed by pooling the cross-covariance of all electrodes in one subject with all electrodes in every other subject (as detailed in60).

where Rkl represents the cross-covariance of all electrodes in subject k with all electrodes in subject l. Here:

where xk(t) is the scalp voltage at time t for subject k, and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{x}}_{k}\) represents the mean scalp voltage for subject k over time.

Within-subject covariance was calculated as the average of each subject’s cross-covariance matrix.

where Rkk is the covariance of EEG signals within the same subject.

Overall, the ISC measure calculates the largest correlation between subjects by maximizing the ratio of between-subject to within-subject covariance. The correlation measure C for each component vi is given by:

High values of C indicate strong similarity across participants. To ensure data stability, the pooled within-subject covariance matrix was regularized66. Both between-subject and within-subject covariance matrices were computed for all participants across all video segments. We selected the three strongest correlated components for the ISC calculation, and the final ISC was computed as the sum of these components:

The ISC analyses were performed in MATLAB (R2019b), and the scripts (links) are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Point-by-point ISC analysis. To analyze the temporal dynamics of neural synchrony, we calculated the ISC over short segments of each video rather than its entire duration. Specifically, we used sliding time windows of 5 s duration and 4 s (80%) overlap24. This approach enabled the visualization of changes in brain-to-brain synchrony over time.

Finally, we visualized the spatial distribution of the ISC by calculating the “scalp projections” of the ISC values through the forward model67. The resulting topoplots illustrate which EEG electrodes contributed the most significantly to each correlated component, providing an estimate of the cortical areas involved.

Statistical analyses

For self-reported preferences, we applied the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess normality, which indicated that the data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05). Therefore, we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test to examine differences across conditions. Significant effects were further explored using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, with p-values adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction68. Adjusted p-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Aggregate ISC scores. To examine whether different videos evoked different levels of neural synchrony, we compared the aggregate ISC values between videos60. Specifically, after confirming the normal distribution of the aggregate ISC values (Shapiro-Wilk test, p > 0.05), we performed a one-way repeated measures ANOVA, with video as the within-subject factor (highways, parks, and boulevards). Significant effects were followed by post hoc paired t-tests, with p-values adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. Adjusted p-values below 0.05 were deemed significant.

Point-by-time point ISC analysis. To explore dynamic brain responses, we conducted a time-resolved ISC analysis. ISC was calculated for each 1-second time window with 80% overlap. Statistical significance was assessed using 1000 permutations, generating surrogate datasets by randomizing EEG signal phases while preserving spectral properties. This approach creates a null distribution for each time window under the hypothesis of no synchronization.

Such a permutation test provided a time-varying statistical significance threshold for ISC over time – the threshold represented the 95% percentile of the random distribution. This approach allowed us to identify at which moment participants, as a group, produced correlated brain responses that were significantly greater than chance24. To correct for multiple comparisons, we applied the false discovery rate (FDR) correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to the p-values obtained from the permutation tests. This correction was performed separately for each component across all time windows. A significance threshold of p < 0.01 (after FDR correction) was applied to identify ISC values exceeding chance levels.

ISC peaks and video content analysis. For each video, we identified peaks of ISCs that crossed the time-varying significance threshold, corresponding to moments of highest synchronization. The video content associated with these peaks was analyzed to identify the events that may have triggered shared attention (for details on Highway 1, Boulevard 1, and Park 1, see Supplementary Table S4). In interpreting the ISC peaks, we considered the contextual significance of the most vivid event that triggered brain-to-brain synchrony across the participants. The peaks reflect genuine attentional shifts synchronized among participants in response to salient urban events.

Frequency band ISC analysis. Additionally, ISCs were also computed within specific frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta and gamma) to investigate frequency-specific neural synchronization in different urban environments. Similar to aggregate ISC scores, for each frequency band we performed a one-way repeated measures ANOVA to compare these ISC values across videos and significant effects were followed by post hoc paired t-tests, with p-values adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

Data availability

The analysis script has been uploaded to GitHub: https://github.com/ML-D00M/urban-environment-eeg-analysis. Data have been made publicly available at: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/ubz5vj2vc706xek5qtpbl/h?rlkey=6cd5z4q7j2k9xok9z83m69uu4&st=ntrkz5im&dl=0.

References

Wilson, E. O. Biophilia (Harvard University Press, 1986).

Kaplan, S. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environ. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973106 (2001).

Ulrich, R. S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment (1983). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4.

Ulrich, R. S. et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 11, 201–230 (1991).

Egner, L. E., Sütterlin, S. & Calogiuri, G. Proposing a framework for the restorative effects of nature through conditioning: conditioned restoration theory. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 145 (2020).

Benedetti, V. et al. Virtual forest environment influences inhibitory control. Land 12, 1523 (2023).

Benedetti, V. et al. Interplay among anxiety, digital environmental exposure, and cognitive control: implications of natural settings. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 14, 323 (2024).

Berto, R., Massaccesi, S. & Pasini, M. Do eye movements measured across high and low fascination photographs differ? Addressing kaplan’s fascination hypothesis. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 185–191 (2008).

Valtchanov, D. & Ellard, C. G. Cognitive and affective responses to natural scenes: effects of low level visual properties on preference, cognitive load and eye-movements. J. Environ. Psychol. 43, 1452 (2015).

Franěk, M., Šefara, D., Petružálek, J., Cabal, J. & Myška, K. Differences in eye movements while viewing images with various levels of restorativeness. J. Environ. Psychol. 57, 10–16 (2018).

Ulrich, R. S. Natural versus urban scenes. Environ. Behav. 13, 523–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916581135001 (1981).

Chang, C. Y., Hammitt, W. E., Chen, P. K., Machnik, L. & Su, W. C. Psychophysiological responses and restorative values of natural environments in Taiwan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 85, 79–84 (2008).

Grassini, S. et al. Processing of natural scenery is associated with lower attentional and cognitive load compared with urban ones. J. Environ. Psychol. 62, 1–11 (2019).

Roe, J., Aspinall, P., Mavros, P. & Coyne, R. Engaging the brain: the impact of natural versus urban scenes using novel EEG methods in an experimental setting. Environ. Sci. 1, 93–104 (2013).

Aspinall, P., Mavros, P., Coyne, R. & Roe, J. The urban brain: analysing outdoor physical activity with mobile EEG. Br. J. Sport Med. 49, 272–276 (2015).

Lin, W. et al. Sitting or walking? Analyzing the neural emotional indicators of urban green space behavior with mobile EEG. J Urban Heal. 97, 142 (2020).

Klimesch, W., Sauseng, P. & Hanslmayr, S. EEG alpha oscillations: the inhibition–timing hypothesis. Brain Res. Rev. 53, 63–88 (2007).

Mathewson, K. E., Gratton, G., Fabiani, M., Beck, D. M. & Ro, T. To see or not to see: prestimulus α phase predicts visual awareness. J. Neurosci. 29, 2725–2732 (2009).

Jensen, O. & Mazaheri, A. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by Inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 186 (2010).

Gould, I. C., Rushworth, M. F. & Nobre, A. C. Indexing the graded allocation of visuospatial attention using anticipatory alpha oscillations. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 1318 (2011).

Haegens, S., Nácher, V., Luna, R., Romo, R. & Jensen, O. α-Oscillations in the monkey sensorimotor network influence discrimination performance by rhythmical Inhibition of neuronal spiking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 108, 19377–19382 (2011).

Hasson, U., Nir, Y., Levy, I., Fuhrmann, G. & Malach, R. Intersubject synchronization of cortical activity during natural vision. Science 80, 303 (2004).

Nastase, S. A., Gazzola, V., Hasson, U. & Keysers, C. Measuring shared responses across subjects using intersubject correlation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 14, 667–685 (2019).

Dmochowski, J. P., Sajda, P., Dias, J. & Parra, L. C. Correlated components of ongoing EEG point to emotionally laden Attention – a possible marker of engagement? Front Hum. Neurosci. 6, 14523 (2012).

Ki, J. J., Kelly, S. P. & Parra, L. C. Attention strongly modulates reliability of neural responses to naturalistic narrative stimuli. J. Neurosci. 36, 3092–3101 (2016).

Dmochowski, J. P. et al. Audience preferences are predicted by temporal reliability of neural processing. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9 (2014).

Cohen, S. S. et al. Neural engagement with online educational videos predicts learning performance for individual students. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 155, 60–64 (2018).

Cohen, S. S., Henin, S. & Parra, L. C. Engaging narratives evoke similar neural activity and lead to similar time perception. Sci. Rep. 71, 1–10 (2017).

Atchley, R. A., Strayer, D. L. & Atchley, P. Creativity in the wild: improving creative reasoning through immersion in natural settings. PLoS One. 7, e51474 (2012).

Williams, K. J. H. et al. Conceptualising creativity benefits of nature experience: attention restoration and Mind wandering as complementary processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 59, 36–45 (2018).

Knyazev, G. EEG delta oscillations as a correlate of basic homeostatic and motivational processes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 677–695 (2012).

Jääskeläinen, I. P., Klucharev, V., Panidi, K. & Shestakova, A. N. Neural processing of narratives: from individual processing to viral propagation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 2563 (2020).

Yarbus, A. L. Eye movements and vision. Eye Move. Vis. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-5379-7 (1967).

Martínez-Soto, J., de la Fuente Suárez, L. A., Gonzáles-Santos, L. & Barrios, F. A. Observation of environments with different restorative potential results in differences in eye patron movements and pupillary size. IBRO Rep. 7, 52 (2019).

Dupont, L., Ooms, K., Duchowski, A. T., Antrop, M. & Van Eetvelde, V. Investigating the visual exploration of the rural-urban gradient using eye-tracking. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 17, 65–88 (2017).

Kaplan, R. & Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. J. Sleep Res. 1989, 340 (1989).

Charloux, A. et al. Time-courses in Renin and blood pressure during sleep in humans. J. Sleep Res. 11, 73–79 (2002).

Gronfier, C., Simon, C., Piquard, F., Ehrhart, J. & Brenberger, G. Neuroendocrine processes underlying Ultradian sleep regulation in man. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 2686–2690 (1999).

Boord, P. R., Rennie, C. J. & Williams, L. M. Integrating ‘brain’ and ‘body’ measures: correlations between EEG and metabolic changes over the human lifespan. J. Integr. Neurosci. 6, 205–218 (2011).

Hlinka, J., Alexakis, C., Diukova, A., Liddle, P. F. & Auer, D. P. Slow EEG pattern predicts reduced intrinsic functional connectivity in the default mode network: an inter-subject analysis. Neuroimage 53, 239–246 (2010).

Schwender, D., Daunderer, M., Klasing, S., Finsterer, U. & Peter, K. Power spectral analysis of the electroencephalogram during increasing end-expiratory concentrations of isoflurane, desflurane and Sevoflurane. Anaesthesia 53, 1422 (1998).

Sleigh, J. W. & Donovan, J. Comparison of bispectral index, 95% spectral edge frequency and approximate entropy of the EEG, with changes in heart rate variability during induction of general anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 82, 666–671 (1999).

Harmony, T. et al. EEG delta activity: an indicator of attention to internal processing during performance of mental tasks. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 24, 14523 (1996).

Schroeder, C. E. & Lakatos, P. Low-frequency neuronal oscillations as instruments of sensory selection. Trends Neurosci. 32, 9–18 (2009).

Lakatos, P., Karmos, G., Mehta, A. D., Ulbert, I. & Schroeder, C. E. Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science 80, 320 (2008).

Will, U. & Berg, E. Brain wave synchronization and entrainment to periodic acoustic stimuli. Neurosci. Lett. 424, 14523 (2007).

Bhattacharya, J. & Petsche, H. Shadows of Artistry: cortical synchrony during perception and imagery of visual Art. Cogn. Brain Res. 13, 1423 (2002).

Knyazev, G. Motivation, emotion, and their inhibitory control mirrored in brain oscillations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31, 2563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.10.004 (2007).

Knyazev, G., Slobodskoj-Plusnin, J. & Bocharov, A. Event-related delta and theta synchronization during explicit and implicit emotion processing. Neuroscience 164, 1588–1600 (2009).

Tei, S. et al. Meditators and Non-Meditators: EEG source imaging during resting. Brain Topogr. 22, 158–165 (2009).

Händel, B. & Haarmeier, T. Cross-frequency coupling of brain oscillations indicates the success in visual motion discrimination. Neuroimage 45, 1040–1046 (2009).

Schroeder, C. E., Lakatos, P., Kajikawa, Y., Partan, S. & Puce, A. Neuronal oscillations and visual amplification of speech. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12, 106–113 (2008).

Baumeister, R. F. Self-regulation, ego depletion, and Inhibition. Neuropsychologia 65, 14523 (2014).

Ferreira, M. E. C., Lima-Junior, D., Faro, H., Roelands, B. & Fortes, L. S. Prolonged cognitive effort impairs inhibitory control and causes significant mental fatigue after an endurance session with an auditive distractor in professional soccer players. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 70, 14523 (2024).

Yang, F., Bao, Z. Y. & Zhu, Z. J. An assessment of psychological noise reduction by landscape plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Heal. 8 (8), 1032–1048 (2011).

Parkinson, C., Kleinbaum, A. M. & Wheatley, T. Similar neural responses predict friendship. Nat. Commun.. 91 9, 1–14 (2018).

Herzog, T. R., Maguire, C. P. & Nebel, M. B. Assessing the restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 23, 159–170 (2003).

van den Berg, M. M. H. E. et al. Autonomic nervous system responses to viewing Green and Built settings: differentiating between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 12, 15860–15874 (2015).

Cao, S. et al. Effects of urban greenway environmental types and landscape characteristics on physical and mental health restoration. Forests 15, 679 (2024).

Cohen, S. S. & Parra, L. C. Memorable audiovisual narratives synchronize sensory and supramodal neural responses. eNeuro 3, 1523 (2016).

Kosonogov, V., Ntoumanis, I., Hajiyeva, G. & Jääskeläinen, I. The role of engagement and arousal in emotion regulation: an EEG study. Exp. Brain Res. 242, 179–193 (2024).

Ntoumanis, I. et al. Altered cerebral processing of videos in children with motor dysfunction suggests broad embodiment of perceptual cognitive functions. J. Pers. Med. 12, 1841 (2022).

van Diepen, R. M., Boksem, M. A. S. & Smidts, A. Reliability of EEG metrics for assessing video advertisements. J. Advert. 54, 506–526 (2025).

Kauppi, J. P., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Sams, M. & Tohka, J. Inter-subject correlation of brain hemodynamic responses during watching a movie: localization in space and frequency. Front. Neuroinform. 4, 14523 (2010).

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Sia, A., Fogel, A. & Ho, R. Features of urban green spaces associated with positive emotions, mindfulness and relaxation. Sci. Rep.. 121 (12), 1–13 (2022).

Blankertz, B., Lemm, S., Treder, M., Haufe, S. & Müller, K. R. Single-trial analysis and classification of ERP components - A tutorial. Neuroimage 56, 14523 (2011).

Haufe, S. et al. NeuroImage on the interpretation of weight vectors of linear models in multivariate neuroimaging. Neuroimage 87, 96–110 (2014).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 57, 1523 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This work/article has been carried out using an HSE automated system of non-invasive brain stimulation with the possibility of synchronous registration of brain activity and registration of eye movements. This article is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University). We thank Evgeny Dotsenko for his assistance in the EEG recording.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K., P.A. and V.K. wrote the main manuscript text, P.A., N.K., I.B. and V.K. designed the methods and algorithm, I.N. and P.A. implemented and tested the algorithm, P.A. and V.K. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 and P.A. and V.M. performed additional data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerimova, N., Akimov, P., Ntoumanis, I. et al. Green urban environments enhance brain-to-brain synchrony. Sci Rep 15, 43524 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27429-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27429-4