Abstract

In current work, a new design of a heat pipe solar collector coupled with a parabolic reflector is numerically analyzed to boost the overall efficiency. The design incorporates several advanced thermal management strategies aimed at improving both heat transfer and energy storage capabilities. The region surrounding the heat pipe inside the evacuated tube is filled with paraffin (RT31), which serves as a phase change material (PCM) and is reinforced with MWCNT nanoparticles to boost its thermal conductivity and accelerate the melting process. In the condenser section, water mixed with hybrid nanoparticles (Ag–MoS2) is employed as the working fluid to significantly enhance convective heat transfer. Moreover, porous metallic foam is embedded within the PCM zone to further improve heat diffusion and reduce melting time. The thermophysical characteristics of the mixtures are incorporated through User-Defined Functions (UDFs), whereas the radiative heat transfer within the evacuated zone is also considered. The outputs reveal that the inclusion of the parabolic reflector notably increases the temperature of the heat pipe, paraffin, and water zones by approximately 31.62%, 31.43%, and 11.82%, respectively. The liquid fraction of the PCM in structure equipped with the reflector is about 2.897 times greater than that of the conventional system, demonstrating a significant improvement in melting performance. Furthermore, as the operating time increases from 10 to 40 min, the temperatures of the heat pipe, paraffin, and water zones rise by 23.77%, 24.97%, and 9.18%, respectively. When all enhancement techniques—including the reflector, hybrid nanoparticles, and porous foam—are combined, the system achieves remarkable temperature increases of 8.81%, 23.61%, and 27.18% for the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones, respectively, with the PCM liquid fraction reaching 3.247 times that of the base design. Overall, this integrated configuration demonstrates a significant advancement over conventional heat pipe solar systems by coupling optical concentration, nanomaterial enhancement, and porous media conduction within a single structure. The results highlight the strong potential of this design for improving solar thermal efficiency, accelerating energy storage, and promoting sustainable energy utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to its abundant availability, and easy accessibility, solar energy is regarded as one of the most favorable sources of renewable energy. Among solar technologies, heat pipe solar collectors have proven to be an efficient solution for converting solar irradiation into usable thermal energy. These systems are widely utilized in domestic water heating, industrial processes, and solar thermal power generation, thanks to their ability to transfer heat with minimal temperature loss and high thermal efficiency. To further improve energy storage and ensure a continuous heat supply, phase change materials (PCMs) are often incorporated into heat pipe systems. PCMs capture and store energy, providing a stable and controlled heat output for sustained system performance. Conventional PCM-based systems, however, are often limited by their inherently low thermal conductivity. To address this challenge, nanoparticles can be dispersed within the PCM, and hybrid nanofluids can be applied in the condenser water. These enhancements improve the paraffin’s effective thermal conductivity and strengthen convective heat transfer within the fluid. Consequently, these improvements lead to a substantial enhancement in the system’s efficiency and energy utilization efficiency. Furthermore, incorporating porous metallic foam within the PCM container has been demonstrated to significantly enhance heat distribution. The foam’s interconnected solid structure creates additional conductive pathways, which reduce temperature gradients, facilitate more uniform melting, and strengthen buoyancy-driven convection within the molten PCM. By combining heat pipe technology, nanoparticle-enhanced PCM, hybrid nanofluids, and porous foam, this integrated approach offers a robust strategy to maximize solar energy capture and storage. It effectively overcomes the limitations of conventional solar thermal systems and provides a pathway toward the development of next-generation, high-performance solar collectors.

Wolde et al.1 conducted a parametric research of a modular solar drying unit combined with a packed-bed thermal storage unit. Their findings revealed that implementing early airflow switching, along with optimizing storage volume and utilizing a single solar collector, can lower overall system costs by nearly 40.53% compared to traditional drying configurations. Xu et al.2 explored various enhancement techniques and practical implementations of photothermal conversion in heat pipe system. They reported that incorporating a solar tracking mechanism enables the collector to align with the sun’s path, thereby concentrating a greater amount of solar radiation onto the absorber surface. Gür et al.3 suggested a new solar-assisted system incorporating nano enhanced PCM (NEPCM) and reported that the combined use of NEPCM and a solar panel enhanced heat retention by approximately 20% compared to a baseline design using conventional PCM. Karabuga4 conducted an economic analysis of hydrogen production using both evacuated tube heat pipe and reflector, reporting that the overall system exergy efficiency was approximately 9.85%. Younis et al.5 investigated the drying behavior, as well as the environmental and economic performance, and reported that the air temperature within the chamber ranged from 44 to 75 °C.

Gurgenc et al.6 examined different configurations of a thermal storage system containing paraffin enhanced with Boron Carbide nanoparticles and reported that the melting duration decreased by approximately 20% in the optimal design, which featured a bottom semi-circular partition. Remlaoui et al.7 scrutinized a numerical research on a solar system and found that the average solar fraction (SF) reached its peak of over 84% during September. Sonkar8 evaluated the efficiency of a heat pipe system integrated with a seawater desalination system and reported that the maximum freshwater condensation rate of 0.154 L/h m2 was achieved in the optimized design. Gür et al.9 investigated the underfloor heating system incorporating a solar panel and NEPCM, reporting that the maximum temperature difference of 4 K was achieved between the optimized design and the baseline configuration. Jayanthi et al.10 compared the use of two distinct nanofluids in a heat pipe and observed that CuO–water produced the highest thermal efficiency, reaching 56.95%.

Despite the extensive research conducted on heat pipe solar collectors, most previous articles have primarily focused on enhancing individual components such as the working fluid, PCM, or absorber surface, while neglecting the synergistic interaction among these subsystems. Conventional systems generally employ either nanofluid-based cooling or PCM-based thermal storage, and only a few have attempted to combine these techniques within an evacuated configuration. However, those limited attempts often overlooked crucial factors such as the thermal behavior of the vacuum region, the radiative exchange effects, and the temperature-dependent variations in thermophysical properties during phase change. Moreover, the impact of porous foam structures and hybrid nanoparticles on improving the heat transfer performance and stability of PCM layers has not been comprehensively investigated within a complete solar heat pipe assembly. To bridge these research gaps, the present work proposes a newly integrated heat pipe solar collector that simultaneously incorporates vacuum insulation, hybrid nanofluid cooling (Ag–MoS2/water), nanoparticle-enhanced PCM (paraffin–MWCNT), and porous metallic foam. This multi-enhancement configuration is modeled under realistic environmental conditions of Babol city, ensuring practical relevance and accuracy. The use of UDFs in ANSYS Fluent enables precise representation of the coupled effects of phase transition, temperature variation, and property evolution, which have rarely been considered in earlier simulations. This comprehensive approach establishes a new pathway for developing high-efficiency solar thermal systems capable of storing and transferring heat more effectively, thereby contributing significantly to sustainable energy utilization and next-generation solar thermal design.

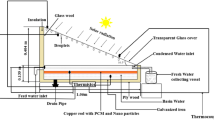

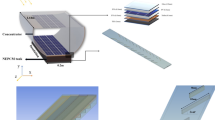

Modeling approach for the novel heat pipe system with concentrator

In this study, a hybrid heat pipe–parabolic reflector system is investigated (Fig. 1). The interior section of system is filled with paraffin wax (RT31), whereas the condenser section utilizes water as the testing fluid for heat exchange. To boost the efficiency of the paraffin, MWCNT nanoparticles are dispersed at a volume fraction of 0.03, enhancing its effective thermal conductivity. Similarly, water in the condenser is enriched with a hybrid nanofluid consisting of Ag and MoS2 nanoparticles, each with a volume fraction of 0.016, to further boost heat transfer. Additionally, metal foam is embedded within the paraffin region. The various simulation cases considered in this study, including different nanoparticle and foam configurations, are summarized in Table 1. In the simulation, the evacuated region surrounding the heat pipe is included, and the S2S radiation model is applied to accurately account for radiative heat transfer within this zone. The orientation of the pipe is set according to the latitude of Babol city, ensuring realistic solar incidence angles. Solar irradiation and ambient air conditions, including wind speed and temperature, are based on meteorological data for May 29, 2024, at noon. Detailed geometrical parameters and the properties of all layers are illustrated in Fig. 211,12,13,14,15,16,17. The initial temperature throughout the entire computational domain is set to 299.15 K. For modeling the paraffin region, the governing equations presented in Refs.18,19,20, have been adopted.

The above equations are applied for modeling paraffin in the existence of metal foam. In the current study, aluminum foam is employed. The permeability (K) of the porous structure is determined using the following relations21:

The density of the paraffin–nanoparticle mixture is determined using the following expression, which incorporates both the phase change behavior of paraffin and its temperature-dependent variations22,23:

Similarly, the specific heat capacity and latent heat of the paraffin–nanoparticle mixture are determined using the following expressions22,23:

The thermal conductivity and viscosity of the paraffin–nanoparticle mixture are calculated applying the following expressions22,23:

All features of the NEPCM were calculated using the aforementioned equations and implemented in ANSYS Fluent through UDFs. The features of the nano-powders employed in this study were summarized in Table 222,23,24,25.

In current study, the heat pipe is represented as a solid zone possessing high thermal conductivity. This assumption facilitates efficient heat transfer along the pipe, minimizing thermal resistance and enabling rapid transport of heat from the absorber to the condenser. Using a material with superior thermal conductivity allows the model to accurately capture the peak thermal performance of the system without being constrained by the inherent conduction limits of the heat pipe material. Such a simplification is commonly adopted in numerical analyses to emphasize system-level behavior and to isolate the effects of working fluids and geometry on overall thermal performance. The governing equation for heat conduction in the solid region is given as follows:

The equations for the fluid behavior within the condenser are given as follows26,27:

The water in the condenser is enhanced with Ag and MoS₂ hybrid nanoparticles, and the thermophysical features of the resulting nanofluid are calculated using the following formulations25,28:

The evacuated region is simulated using the S2S radiation model, with the following formulations applied29,30:

For the current unsteady simulation, ANSYS Fluent was employed. The unsteady terms were discretized using an implicit scheme, and the enthalpy–porosity approach was applied to model melting. Convergence was ensured by maintaining the residuals of all governing equations below 1e−5.

Results and discussion

In this article, a new configuration of a heat pipe–based solar collector is introduced to boost the efficiency of solar energy harvesting, storage, and conversion. The system is specifically designed according to the climatic conditions of Babol city, where the optimal tilt angle, solar irradiation intensity, and ambient air characteristics have been carefully selected to ensure realistic operation. The collector is composed of four key thermal regions: the evacuated zone, the solid heat pipe region, PCM zone surrounding the heat pipe, and the water condenser section. To enhance the useful heat recovery within the condenser region, a hybrid nanofluid composed of Ag–MoS2 nanoparticles dispersed in water is utilized. In the PCM zone, paraffin wax is selected as the base material for thermal storage, which is further reinforced with MWCNTs to boost thermal conductivity and reduce melting time. Additionally, the PCM zone is embedded with porous metallic foam, which acts as a conductive network that accelerates both melting and solidification, enhancing energy storage and release efficiency. To capture the complex variations in thermophysical properties during phase transition and temperature change, user-defined functions (UDFs) are developed and implemented in ANSYS FLUENT. The integration of hybrid nanofluid cooling, nanoparticle-enhanced PCM, and porous foam within an evacuated heat pipe structure introduces a multi-scale enhancement approach that has rarely been investigated in the literature. Overall, this new hybrid design represents an important step toward the development of advanced solar thermal systems capable of achieving higher efficiency, greater energy storage density, and improved operational stability.

To assess the optical efficiency of the heat pipe solar system, simulations were conducted for both configurations—with and without a parabolic reflector—using two specialized software tools. Tonatiuh was used to model the system without a reflector, while SolTrace was utilized for the configuration including the parabolic reflector. Figures 3 and 4 present the resulting distributions of the concentration ratio (CR) for the two cases. The parabolic reflector in this study has a reflectivity of approximately 0.8. Using the solar irradiation data, the local heat flux distribution on the absorber surface was calculated, capturing the spatial variation of solar energy input. This space-dependent heat source was then implemented into the ANSYS Fluent simulations through a UDF, allowing accurate coupling of the optical analysis with the thermal and fluid dynamics modeling.

The reliability of the numerical method was confirmed through a two-step validation procedure. In the first step, the phase change behavior of paraffin was simulated based on previous work31, where RT82 was used within a porous zone. The hot wall temperature was set to 343 K, while the initial PCM temperature was 366 K. Figure 5a offers a comparison between the predicted LF and the reference data, demonstrating excellent agreement with a maximum error of less than 5%. In the second step, the behavior of the heat pipe in the presence of PCM was evaluated32. In this case, Rubitherm 55 was used as the PCM, and the hot wall was maintained at T = 335 K. The predicted LF values were compared with published results, as depicted in Fig. 5b, and the maximum error was found to be less than 2.3%. Overall, the validation outputs prove that the proposed numerical setup effectively reproduces the phase transition and behavior of the heat pipe–PCM configuration, underscoring the dependability and strength of the simulation method applied in this work.

A sensitivity analysis has been conducted to verify the reliability of the simulation outputs by examining how variations in mesh density and time-step size affect the predicted liquid fraction (LF) for Case 3. Figure 6 presents the LF values obtained for various grid resolutions and different time-step levels. The results indicate that increasing the mesh density and decreasing the time step improves the precision of the numerical solution; however, beyond a certain threshold, further refinement yields negligible changes in LF while significantly increasing computational cost. Based on this analysis, a mesh consisting of 1,187,697 elements combined with ∆t of 0.05 s was selected as the optimal configuration. This choice provides an accurate solution while maintaining computational efficiency, balancing numerical accuracy with reasonable simulation time. The corresponding mesh structure applied in the numerical model is demonstrated in Fig. 7, showing the discretization used for the PCM, heat pipe, and condenser regions. This careful selection of mesh and ∆t ensures that the subsequent simulation results are both reliable and computationally efficient.

Figures 8, 9, 10 and 11 illustrate the temporal evolution of temperature in the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones for all simulated cases. In these figures, the legends for the water and PCM zones represent the mixture properties, reflecting the combined influence of the nanoparticles and the base fluids. According to Table 1, Case 1 represents the base system without any enhancement techniques, Case 2 includes a parabolic reflector, Case 3 incorporates the reflector along with nanoparticles, and Case 4 combines the reflector, nanoparticles, and porous foam. Upon exposure to solar irradiation, the paraffin begins to melt first, absorbing thermal energy. Afterward, the heat pipe transports the heat toward the condenser zone, leading to a gradual rise in the water temperature. As expected, the temperature in all three zones increases over time due to continuous solar heating and heat transfer from the PCM. Between 10 and 40 min, the PCM temperature rises by approximately 5.92%, 34.65%, 34.17%, and 24.97% for Cases 1 through 4, respectively. Over the same period, the water temperature increases by 1.71%, 13.72%, 15.31%, and 8.18%, and the heat pipe temperature rises by 4.76%, 37.5%, 37.2%, and 23.77% for Cases 1 to 4, respectively. These results indicate that Case 2, which includes the parabolic reflector, exhibits the largest temporal temperature variation, highlighting the strong effect of concentrated solar irradiation. After 40 min of operation, the inclusion of a parabolic reflector enhances the temperatures of the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones by approximately 11.82%, 31.43%, and 31.62%, respectively, compared to the base case. The additional use of nanoparticles and porous foam (Case 4) further improves thermal performance, raising the temperatures of the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones by 8.81%, 23.61%, and 27.18%, respectively, relative to Case 1.

Figure 12 depicts the temporal variation of LF for all four simulated cases. As the simulation progresses, heat penetrates deeper into the PCM domain, gradually converting solid paraffin to liquid and producing a clear increasing trend in LF over time. At t = 40 min, the LF values have increased approximately 4.68, 4.22, 4.15, and 3.88 times compared to their respective values at t = 10 min for Cases 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The application of a parabolic reflector (Case 2) markedly enhances heat absorption in both the PCM and water zones. The LF in Case 2 increases by about 2.897 times. This occurs because the reflector concentrates solar irradiation onto the system, boosting the local heat flux and accelerating the melting, thereby improving energy storage and overall thermal efficiency. The introduction of nanoparticles in both the PCM and water zones (Case 3) further increases the LF by approximately 2.84% relative to Case 2. Nanoparticles in the paraffin improves its effective thermal conductivity, facilitating faster and more uniform heat distribution, while hybrid nanoparticles in the water coolant improve convective heat transfer, reduce thermal resistance, and stabilize temperature distribution throughout the condenser. These effects collectively contribute to higher system efficiency. Finally, embedding porous foam within the PCM region (Case 4) leads to an additional LF increase of about 8.98%. The highly conductive metal foam creates an interconnected network for heat conduction, accelerating energy transfer from hotter to cooler regions within the PCM and promoting uniform melting. When all three enhancement strategies—reflector, nanoparticles, and porous foam—are applied together, the LF of Case 4 reaches approximately 3.247 times that of the base configuration.

Figures 13, 14 and 15 illustrate LF, temperature, and velocity distributions within the PCM for Cases 1, 2 and 3 from both sectional and lateral perspectives. The results reveal that, in all cases, the top region exhibits a higher LF due to the action of buoyancy-driven convection, which transports warmer, lower-density fluid upward while cooler, denser material remains at the bottom. Once the melting starts, the top portions of the PCM attain higher temperatures than the lower layers due to buoyancy-driven heat transfer. In the absence of a reflector, the upper PCM region receives a concentration ratio (CR) of approximately 0.632, while the inclusion of a parabolic reflector significantly increases the heat flux to the lower PCM region, raising its CR to about 1.193. Hence, enhanced heat absorption at the lower section promotes faster melting and leads to a higher liquid fraction in that area. Within the molten PCM, natural convection causes the warmer fluid to rise, generating eddy structures and circulating flows in the upper zones. In the early phase, when most of the PCM is still solid, conductive heat transfer prevails, resulting in higher temperatures at the bottom region where solar radiation is most concentrated. As melting progresses, buoyancy-driven convection becomes increasingly significant. Hot, less dense PCM rises toward the top, while cooler, denser PCM remains near the bottom. In inclined tubes, convection cells develop along the surface, enhancing vertical heat transport. Over time, the upper regions of the PCM may become hotter than the lower regions, despite receiving lower direct irradiation, as heat is continuously carried upward by the rising molten PCM. This dynamic process highlights the combined effects of conduction, natural convection, and optical concentration in achieving uniform PCM melting and efficient thermal energy distribution.

Figure 16 illustrates the transient temperature distribution of Case 4 at various simulation times. In this configuration, aluminum porous foam with high porosity is embedded within the PCM region surrounding the heat pipe. The primary purpose of incorporating this metallic foam is to enhance the conduction mode, which is inherently limited in pure paraffin. In a conventional system without foam, heat propagates mainly by conduction through the PCM, leading to slow thermal diffusion and the formation of steep temperature gradients between the lower (hot) and upper (cold) regions. When the aluminum foam is introduced, its interconnected solid structure provides multiple high-conductivity pathways for heat transfer. Heat absorbed from the region exposed to higher solar irradiation at the bottom is rapidly transmitted to the upper zones. This mechanism significantly reduces local temperature gradients, leading to more uniform isotherms. The foam acts as a heat-spreading network, accelerating the melting process by transferring energy evenly across the phase change interface. Over time, as more PCM melts, buoyancy-driven convection becomes more pronounced due to the temperature-dependent density variations within the molten PCM. The improved thermal conduction offered by the foam facilitates this convective flow, leading to a faster and more uniform melting front that progress upward. Consequently, the PCM achieves uniform melting, elevated average temperatures, and improved heat storage efficiency compared to systems without foam. The interplay of heat conduction through the metallic foam framework and convection within the molten PCM markedly enhances overall thermal performance and energy utilization.

Figures 17 and 18 illustrate the temperature and velocity contours within the condenser zone of Case 4 at different operating times. In this configuration, the condenser section receives heat indirectly from the evaporator and PCM regions through the heat pipe structure. Once absorbed, the heat moves through the wall of the heat pipe and is passed on to the hybrid nanofluid flowing through the condenser, where it is effectively utilized for thermal exchange. This hybrid nanofluid, which contains Ag–MoS2 nanoparticles, serves as the working fluid and exhibits enhanced thermal conductivity compared to pure water. When heat is conveyed from the pipe wall into the fluid, the resulting temperature increase causes the fluid density to decrease. This density gradient initiates buoyancy-driven natural convection, which promotes fluid circulation within the condenser region. In the initial phase of heating, significant temperature variations occur close to the outer wall, primarily due to conduction, while the interior fluid region remains relatively cold. As time progresses, heat is gradually distributed throughout the fluid domain through convection, resulting in a more uniform temperature field. The development of thermal plumes becomes evident near the upper region of the heat pipe as warmer fluid ascends and cooler fluid descends to replace it, creating a natural convective loop. This circulation enhances the overall heat transfer within the condenser and promotes faster energy transport away from the heat pipe wall. With increasing operating time, both the intensity of the thermal plume and the velocity magnitude of the fluid increase, signifying stronger convective motion. The bottom region of the condenser consistently shows lower temperatures due to the reduced buoyancy forces and weaker circulation near the base. The formation of eddy structures and recirculation zones above the heat pipe further signifies the shift from conduction to convection. The observed flow circulation is key to achieving temperature balance and facilitating more effective heat dissipation from the condenser region. Overall, the contours clearly demonstrate that the use of hybrid nanofluid in Case 4 significantly improves heat transport mechanisms within the condenser zone. The combination of nanoparticle-enhanced conductivity and buoyancy-induced convection leads to a more effective thermal exchange process, ensuring rapid and uniform heating of the working fluid. This enhanced convective behavior contributes to the superior performance of the hybrid heat pipe solar system compared with conventional configurations.

Conclusion

This study introduced an innovative design of a heat pipe system that integrates multiple enhancement strategies. The system was designed based on the real climatic conditions of Babol city, considering the optimal tilt angle, solar irradiation, and ambient air characteristics. The proposed configuration consists of four thermally interactive zones—namely, the evacuated region, the solid heat pipe zone, the PCM section surrounding the pipe, and the condenser region filled with water. The radiative behavior within the vacuum zone was modeled using the S2S approach, while the heat pipe was represented as a high-conductivity solid to ensure accurate prediction of the energy balance and thermal resistance. To intensify the heat transfer process, a hybrid nanofluid was utilized in the condenser region. Moreover, the PCM region, composed of paraffin wax enhanced with MWCNT nanoparticles and reinforced with porous foam, facilitated faster melting and solidification while improving the stability of energy storage. UDFs were developed and implemented in ANSYS Fluent to incorporate the variations in temperature and phase change characteristics of the working materials. In this study, four different configurations of a heat pipe system were numerically investigated to evaluate the combined effects of a parabolic reflector, nanoparticle enhancement, and porous foam integration on the system’s thermal and storage performance. Case 1 represents the base configuration of the system without any enhancement techniques. Case 2 incorporates a parabolic reflector to intensify solar radiation absorption. Case 3 extends the design by adding nanoparticles to both the PCM and water regions in the presence of the reflector. Finally, Case 4 introduces a comprehensive enhancement strategy that combines all three techniques—porous foam embedded in the PCM region, nanoparticle augmentation in both the PCM and condenser water, and the addition of concentrator. The findings reveal the superior performance of the modified systems over the baseline. Nanoparticle dispersion increases the PCM’s LF by about 2.84%, and the presence of porous foam elevates it further by around 8.98%, reflecting faster melting and improved energy storage. When all three enhancement techniques are employed simultaneously, the temperatures of the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones increase by 8.81%, 23.61%, and 27.18%, respectively, with the overall liquid fraction rising by approximately 224.71% after 40 min of operation. Additionally, as time progresses from 10 to 40 min in Case 4, the temperatures of the water, PCM, and heat pipe regions increase by 9.18%, 24.97%, and 23.77%, respectively, demonstrating the system’s stable and continuous thermal response under prolonged exposure. The inclusion of the reflector alone also produces a noticeable improvement, increasing the temperatures of the water, PCM, and heat pipe zones by 11.82%, 31.43%, and 31.62%, respectively, after 40 min, while the corresponding liquid fraction in Case 2 is about 2.897 times greater than that of the base case. These results confirm that the combined application of optical concentration, nanoparticle enhancement, and porous media conduction substantially strengthens the system’s overall heat transfer and thermal storage performance. In summary, the proposed hybrid heat pipe solar collector demonstrates remarkable potential for achieving higher efficiency, faster PCM melting, and more stable thermal operation compared to conventional designs. The synergistic integration of a parabolic reflector, NEPCM, hybrid nanofluid, and porous foam creates a robust energy conversion mechanism that significantly enhances solar energy utilization.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Wolde, I., Calderón-Vásquez, I., Molina, M., Pailahueque, N. & Cardemil, J. M. Parametric analysis of a modular solar drying and packed bed thermal energy storage system. Sol. Energy. 300, 113764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2025.113764 (2025).

Xu, Y. et al. Enhancement strategies and engineering applications of photothermal conversion for evacuated tube solar collectors coupling heat pipes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 220, 115893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2025.115893 (2025).

Muhammed Gür, E., Gürgenç, H., Coşanay, Hakan, F. & Öztop January, Solar-assisted radiant heating system with nano-B4C enhanced PCM for nearly zero energy buildings. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 65, 105544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105544 (2025).

Karabuga, A. Exergy and economic analysis of evacuated tube heat pipe solar collector and parabolic trough solar collectors based power, cooling and hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 146, 150006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.06.196 (2025).

Younis, O. S. et al. Drying characteristics, environmental and economic analysis of a solar dryer with evacuated tube solar collector for drying nile tilapia slices. Sci. Rep. 15, 9822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94194-9 (2025).

Ezgi Gurgenc, M., Gur, H., Cosanay, T., Gurgenc, H. F. & Oztop. Effects of position of semi-circular body on melting of a novel B4C/RT44HC PCM nanocomposite in a closed space. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 65, 105628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105628 (2025).

Remlaoui, A. et al. Numerical simulation of a forced circulation solar water heating system. Sci. Rep. 14, 28999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80576-y (2024).

Sonkar, M. & Naik, B. K. Performance assessment of sustainable evacuated tube heat pipe solar collector driven seawater desalination system. Solar Compass. 14, 100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solcom.2025.100112 (2025).

Muhammed Gür, Hakan, F., Öztop, F. & Selimefendigil. Analysis of solar underfloor heating system assisted with nano enhanced phase change material for nearly zero energy buildings approach. Renew. Energy. 218, 119265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.119265 (2023).

Jayanthi, N., Venkatesh, M., Kumar, S., Babu, R. R. & Prabakar, S. P. Experimental evaluation of CuO and Al2O3 nanofluids for enhanced heat transfer in evacuated tube heat pipe solar collectors. Results Eng. 27, 106299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.106299 (2025).

Gong, J., hao Sun, Z., Wang, J. & Lund, P. D. Performance studies of novel all-glass heat pipe evacuated collector tube integrating numerical simulation and experiment method. Solar Energy. 253, 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.02.028 (2023).

Pawar, V. R. & Sobhansarbandi, S. CFD modeling of a thermal energy storage based heat pipe evacuated tube solar collector. J. Energy Storage. 30 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101528 (2020).

Farjallah, R., Chaabane, M., Mhiri, H., Bournot, P. & Dhaouadi, H. Thermal performance of the U-tube solar collector using computational fluid dynamics simulation. J. Solar Energy Eng. Trans. ASME. 138 (6). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4034517 (2016).

Ma, L., Lu, Z., Zhang, J. & Liang, R. Thermal performance analysis of the glass evacuated tube solar collector with U-tube, Building and environment. Sep 45 (9), 1959–1967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.01.015 (2010).

Lim, C. S. L. & Sobhansarbandi, S. CFD modeling of an evacuated U-tube solar collector integrated with a novel heat transfer fluid. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 52 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102051 (2022).

Tiari, S. & Qiu, S. Three-dimensional simulation of high temperature latent heat thermal energy storage system assisted by finned heat pipes. Energy. Conv. Manag. 105, 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2015.08.004 (2015).

Staliulionis, Z. et al. Thermal modelling and design of on-board DC-DC power converter using finite element method. Elektronika ir. Elektrotechnika. 20 (7), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.eee.20.7.8022 (2014).

Mahdi, J. M. & Nsofor, E. C. Melting enhancement in triplex-tube latent heat energy storage system using nanoparticles-metal foam combination. Appl. Energy. 191, 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.11.036 (2017).

Hamada, A., Emam, M., Refaey, H. A., Moawed, M. & Abdelrahman, M. A. Investigating the performance of a water-based PVT system using encapsulated PCM balls: an experimental study. Energy. 284, 128574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128574 (2023).

Choi, S. H., Sohn, D. K. & Ko, H. S. Experimental study on PVT–PCM system performance using bubble-driven flow. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Transf. 146, 106919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2023.106919 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Numerical investigation and optimization of the melting performance of latent heat thermal energy storage unit strengthened by graded metal foam and mechanical rotation. Renew. Energy. 227, 120537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120537 (2024).

Hai, T. et al. Optimization of nano-finned enclosure-shaped latent heat thermal energy storage units using CFD, RSM, and enhanced hill climbing algorithm. Sci. Rep. 1512486. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96599-y (2025).

Anter, A. G., Sultan, A. A., Hegazi, A. A. & El Bouz, M. A. Thermal performance and energy saving using phase change materials (PCM) integrated in Building walls. J. Energy Storage. 67, 107568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107568 (2023).

Singh, D. K. Free convection with MWCNT/water nanofluid having varying aspect ratio of MWCNT nanoparticle in thermally undulated enclosures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 178, 105626, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.105626 (2020).

Abbas, M., Khan, N., Hashmi, M. S. & Younis, J. Numerically analysis of Marangoni convective flow of hybrid nanofluid over an infinite disk with thermophoresis particle deposition. Sci. Rep. 13, 5036. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32011-x (2023).

Elsaady, W., Moughton, C., Nasser, A. & lacovides, H. Coupled numerical modelling and experimental analysis of domestic induction heating systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 227, 120170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120170 (2023).

Alnakeeb, M. A., Abdel Salam, M. A., Hassab, M. A. & El-Maghlany, W. M. Numerical study of thermal and electrical performance of a new configuration of hybrid photovoltaic solar panel phase-change material cooling system. J. Energy Storage. 97, 112945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112945 (2024).

Nadeem, M., Siddique, I., Awrejcewicz, J. & Bilal, M. Numerical analysis of a second-grade fuzzy hybrid nanofluid flow and heat transfer over a permeable stretching/shrinking sheet. Sci. Rep. 12, 1631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05393-7 (2022).

Lu, X. & Wang, T. Investigation of radiation models in entrained-flow coal gasification simulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 67, 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.08.011 (2013).

Ben-Mansour, R., Abuelyamen, A. & Mokheimer, E. M. A. CFD analysis of radiation impact on Stirling engine performance. Energy. Conv. Manag. 152, 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.09.056 (2017).

Mahdi, J. M. & Nsofor, E. C. Solidification enhancement in a triplex-tube latent heat energy storage system using nanoparticles-metal foam combination. Energy 126, 501e512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.03.060 (2017).

Mahdavi, M., Tiari, S. & Pawar, V. A numerical study on the combined effect of dispersed nanoparticles and embedded heat pipes on melting and solidification of a shell and tube latent heat thermal energy storage system. J. Energy Storage. 27, 101086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.101086 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and M.J.S. carried out the simulations and analyzed the results. M.S. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, while M.J.S. generated the figures. H.R.A. and L.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript and verified the validation procedures. All authors contributed to the final review and approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikholeslami, M., Sarmadi, M.J., Momayez, L. et al. Development of a novel solar system incorporating a heat pipe within a porous enclosure for simulating paraffin melting. Sci Rep 15, 43465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27501-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27501-z