Abstract

In this study, we introduce a refractive index (RI) sensor based on topological interface states (TISs) in one-dimensional photonic crystals. The design incorporates a porous cap layer positioned at the interface between two photonic crystals, enabling the support of TIS modes. Owing to its porosity, the cap layer makes the device particularly suitable for aqueous and biological analytes, and the reported analysis focuses on the RI range relevant for such biosensing applications. The behavior of TISs is investigated through the transfer matrix method by tuning the physical parameters of the cap layer, and the findings are further validated using FEM simulations. The sensing characteristics are examined as a function of structural parameters, showing robust performance across the RI range of 1.33–1.43 with an almost constant sensitivity of ~ 745 nm/RIU. Although performance optimization was not the main goal, results reveal that in the fully porous case—where the analyte itself serves as the defect layer—the sensitivity can reach up to 941 nm/RIU. As a practical demonstration, the sensor was applied to glucose detection. For concentrations up to 36 g/L and at 85% porosity, the sensitivity, figure of merit, and detection limit were found to be 803 nm/RIU, 6.5 × 10⁶, and 1.4 × 10⁻⁷ RIU, respectively, surpassing previously reported works in all major metrics. These findings highlight the potential of the proposed structure for diverse biosensing applications, while noting that similar principles could be applied to other RI ranges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, topological photonics has garnered significant attention for its ability to provide unprecedented robustness and enhanced functionality in light manipulation1. A key feature in this field is the topological interface state (TIS), a localized optical mode formed at the boundary between two structures with distinct bulk band topologies. TISs exhibit inherent immunity to fabrication imperfections, structural defects, and disorder, while enabling strong light confinement and intensified light–matter interactions2,3. One-dimensional (1D) periodic photonic systems offer a straightforward yet effective framework for investigating topological phenomena. A TIS arises when the bulk band topologies—characterized by Zak phases and related to surface impedance—differ on either side of the interface4,5. The TIS has paved the way for advancements in a variety of devices, including topological lasers6, waveguides7,8, filters9, optical sensors10, and cavity lasers11. A fundamental advantage of free-space topological photonic crystal (PC) sensors over evanescent-wave counterparts is that all light reaching the detector traverses the sensing medium. This results in a stronger overlap between the optical field and the sample, leading to enhanced sensitivities12. Coupled with the simple geometry of 1D PCs, this facilitates integration into compact, cost-effective devices. Compared to complex 2D and 3D structures, 1D topological PCs provide easier fabrication and simpler design, while enabling advanced functionalities such as sensing enhancements via mirror heterostructures and coupling between topology and Fano resonances13. Consequently, these systems are well suited for a variety of sensing applications, including glucose detection in blood and aqueous solutions—critical for medical diagnostics, biotechnology, and food analysis—where detection of low concentrations is essential14,15,16. Unlike alternative sensing methods such as surface plasmon resonance or mid-infrared photoacoustic techniques which involve high fabrication costs and complexity, 1D topological PCs can achieve near-unity transmission (up to 99%), high quality (Q) factors, and excellent figures of merit (FOM) with low detection limits. Recent studies on one-dimensional topological photonic crystals (1D-TPhCs) have demonstrated a wide range of advanced sensing functionalities. For example, a glucose sensor with a high sensitivity of 604 nm/RIU and a low detection limit has been developed17, along with a RI sensor achieving 254 nm/RIU sensitivity18 and a gas sensor exhibiting an ultra-high sensitivity of 888 nm/RIU19. Complete light absorption has been realized in a graphene-integrated 1D-TPhC heterostructure20, while Su et al. introduced a high-performance biosensor based on Tamm plasmon polaritons in 1D-TPhCs21. In addition, investigations revealed that a polarization-independent, ultra-sensitive biosensor employing 1D-TPhCs can achieve extremely high figures of merit (FOM)22. Overall, these configurations have significantly advanced sensor technologies, including applications in temperature and RI detection23,24,25,26.

Porous silicon (PSi) has also been utilized in parity-time symmetric photonic crystals to amplify resonant peaks, making them more distinct and improving biosensing performance27. Owing to its extremely high surface area and abundant pore structures that facilitate molecular adsorption, PSi has shown significant promise in biosensors and biomedical applications28,29,30. Typically fabricated via electrochemical etching of crystalline p-type silicon substrates in ethanol–hydrofluoric acid solutions31, PSi pore sizes can be precisely tailored by adjusting doping levels, etching current densities, and solution concentrations32, optimizing its sensing properties.

In the present work, inspired by the unique attributes of porous silicon and leveraging the characteristics of topological interface states, as well as building upon our recent study highlighting the influence of the cap layer’s physical properties on tuning TIS modes33, we propose and investigate a novel 1D centrosymmetric photonic crystal structure. This design incorporates a porous silicon cap layer between two photonic crystals, functioning simultaneously as a cavity supporting TISs and as an active sensing medium to achieve enhanced sensing performance. In contrast to previous studies that utilized defect modes within the Kretschmann configuration—where sensing performance depends on minimizing the reflection coefficient—our proposed design allows the entire incident light to pass through the sensing medium before reaching the detector, thereby improving sensor efficiency22,23,24,25. Moreover, in heterogeneous photonic crystals where the conventional central defect is entirely filled with an aqueous medium, the structure needs to be separated into two distinct photonic crystals, which is clearly different from the traditional one-dimensional defect-based photonic crystal configuration26. However, by incorporating a porous layer, the entire configuration can be realized as a single, continuous, and integrated structure. The presence of porosity also offers the advantage of supporting well-defined defect mode characteristics, while enabling the sensing properties to be suitably engineered through the porosity parameter. PSi is an ideal substrate for detecting concentrations like glucose in blood and aqueous solutions, making it useful for medical and commercial purposes. Because reliable and sensitive glucose sensors play a crucial role in clinical diagnostics, biotechnology, and food quality analysis, there has been continuous and strong interest in advancing glucose sensor technology14. We begin by examining the sensing performance of the system through variations in key physical parameters, including the thickness and porosity of the silicon, and compare the results with recent studies. The results show that the proposed structure delivers superior sensing capabilities relative to previously reported designs. In particular, the sensor features a wide dynamic range and maintains nearly constant sensitivity over a broad range. For benchmarking, its performance in detecting glucose concentration is analyzed in greater detail and compared with earlier works. The analysis is conducted using the transfer matrix method for evaluating the optical properties, while selected cases are further studied using the finite element method implemented in COMSOL to obtain field profiles, and the results from both approaches are compared. Section 2 introduces the theoretical model and framework, detailing the numerical analysis performed using the transfer matrix method (TMM). It investigates the characteristics of topological interface states (TISs) under different structural configurations, with particular attention to their relevance for biosensing performance metrics. Finally, Sect. 3 presents the conclusions of the work.

Structure, theory and results

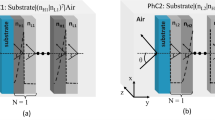

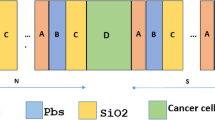

We begin our study by examining a topological photonic crystal (TPhC) structure formed through the combination of two centrosymmetric photonic crystals, denoted as PhC1 and PhC2, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The configuration under consideration is inspired by our recently reported topological PhC designs33, with the distinction that the conventional cap layer is replaced here by a porous silicon layer, thereby enabling the investigation of its sensing performance.

The proposed structure is constructed by joining two finite photonic crystals, each characterized by a lattice constant d and comprising N unit cells. The left-hand photonic crystal (PhC1) consists of alternating dielectric layers A and B, whereas the right-hand photonic crystal (PhC2) is composed of layers C and D. In the limiting case where the thickness of the silicon layer approaches zero, the resulting configuration corresponds to bare interface states arising between two binary photonic crystals.

A schematic diagram of the heterostructure is presented. The centrosymmetric unit cell of each photonic crystal is delineated between two vertical dashed lines, each possessing a thickness of d. At the central region of the structure, a porous silicon layer is incorporated, functioning as the sensing medium.

The working wavelength is chosen to be around 1.55 μm, which is the most common operating window for biosensing applications due to its low optical loss in biological media and compatibility with standard optical communication technologies. In this configuration, layers A and C consist of silicon (Si) with a RI of 3.45, layer B is composed of hafnium dioxide (HfO₂) with a RI of 1.98, and layer D is formed from silicon dioxide (SiO₂) with a RI of 1.4634. These materials and their respective parameters are typical values that will not compromise the validity of the results. The layer thicknesses are chosen as 127 nm for layer A, 565 nm for layer B, 275 nm for layer C, and 417 nm for layer D. The lattice constant is set to d = 692 nm for both photonic crystals, with thickness ratios of dA/d = 0.1837 and dB/d = 1 − dA/d, as well as dC/d = 0.3970 and dD/d = 1 − dC/d, following the ratios established in our recent work33. These parameters are selected to realize a TIS near the wavelength of 1550 nm, utilizing both the transfer matrix method and the finite element method for numerical verification. The refractive index of porous silicon can be determined using the following relation27,35:

where p denotes the porosity, and nSi and ns represent the refractive indices of silicon and the analyte filling the pores, respectively.

The band structure of the binary PhCs for normal incidence of light is determined by36,37,38,39:

where \({k_{iz}}=(\omega /c){[{\varepsilon _i}{\mu _i}]^{1/2}}\), \({F_i}={k_{iz}}/{\varepsilon _i}\), (i = A, B). Here, \({\varepsilon _i}\) (\({\mu _i}\)) is the permittivity (permeability) of i’th layer, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, and c is the light speed in vacuum and \(\:{K}_{B}\:\)denotes the Bloch wavevector.

Panels (a) and (b) show the band structures of PhC1 and PhC2 for the normal incidence, respectively, with the Zak phases indicated for each individual band. The cyan and orange strips correspond to gaps with \(\:{\upzeta\:}<0\) and \(\:{\upzeta\:}>0\), respectively. (c) The transmission spectrum of the proposed PhC1|silicon layer|PhC2 heterostructure with 6-unit cells for each photonic crystal is presented. The existence of a TIS at \(\:\text{d}/{\uplambda\:}=0.4495,\) corresponding to a wavelength of 1540 nm, is clearly observed within the shared second bandgap displayed in this panel. The vertical axes represent the normalized frequency of light. In panels (a) and (b), the horizontal axes correspond to the normalized Bloch wavevector, while in panel (c) the horizontal axis indicates the transmission of the structure.

Figure 2 presents the band structure of PhC1 in panel (a) and that of PhC2 in panel (b). For each isolated band n, the Zak phase takes quantized values of either 0 or π, and is defined as4:

Here, \(\:\epsilon\:\left(z\right)\) denotes the spatially varying permittivity, while \(\:{u}_{mK}\left(z\right)\) is the Bloch eigenfunction of the electric or magnetic field in the n-th passband. The term in brackets represents the Berry connection, evaluated over the unit cell. The calculated Zak phases for each band are shown in panel (c) of Fig. 2.

The existence of a TIS can be inferred from the cumulative Zak phase below a given bandga The surface impedance of the n-th gap, \(\:{Z}_{S}^{n}\), is connected to the free-space impedance, \(\:{Z}_{0}\) , by the relation: \(\:{Z}_{S}^{n}/{Z}_{0}=i{\zeta\:}^{n}\).

To establish the presence of interface states, one must identify a common gap for which the signs of \(\:{\zeta\:}^{n}\) differ in the two photonic crystals forming the heterostructure. The sign of \(\:{\zeta\:}^{n}\) is determined using the formula4:

where l is the number of band-crossing points located below the n-th ga In the band diagrams of PhC1 and PhC2, regions with \(\:\zeta\:<0\:\)are highlighted in cyan, whereas regions with \(\:\zeta\:>0\:\)are marked in orange. As depicted in panels (a) and (b), the second bandgap corresponds to a change in the Zak phase between bands 1 and 2, accompanied by a sign reversal of the surface impedance. Consequently, when PhC1 is placed on the left and PhC2 on the right, a TIS is expected to emerge within the second bandga This feature is confirmed by numerically analyzing the transmission spectrum of a heterostructure composed of PhC1 (six-unit cells) on the left and PhC2 (six-unit cells) on the right, both placed in vacuum. A non-porous silicon layer, serving as a simple defect layer with thickness d, is embedded at the center. The corresponding transmission spectrum under normal electromagnetic wave incidence is illustrated in panel (c) of Fig. 2. The calculation is performed using the well-established transfer matrix method (TMM)40.

By considering this topological mode, we will investigate the sensing performance of the structure. The objective of the present work is not solely to optimize the design for achieving the highest possible sensitivity, but rather to develop a sensor that offers a broad dynamic range. Following this analysis, the sensor will be further examined for a specific application—glucose detection. The sensitivity (S), figure of merit (FoM), quality factor (Q), and limit of detection (LoD) are evaluated to assess the performance of the model using the following equations41:

Here, FWHM denotes the full width at half maximum of the peaks., and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{R}\) represents its resonance position.

Figure 3 presents the transmittance spectra of the TPhC under normal light incidence. In this configuration, six periods are placed on each side of the interface, and the cap layer thickness is fixed at dcap=1d. Two scenarios are considered: p = 0 and p = 1, with a sample RI of ns=1.33. The parameter p denotes the porosity of the cap layer, ranging from 0 to 1. These cases represent a silicon defect cap layer and a liquid medium with a RI of 1.33, where the TIS modes emerge at 1563 nm and 1603 nm and shift by about 40 nm as the porosity varies from 0% to 100%.

To illustrate the effect of cap layer porosity at the interface on the TISs, Fig. 4 presents the variation of TISs with porosity for a thickness of dcap= d, with a typical sample RI of ns=1.33.

The transmittance map of the heterostructure is presented as a function of the cap layer porosity for \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{cap}}=\text{d}\), considering a sample RI of \(\:{\text{n}}_{\text{s}}=1.33\), within the second common bandgap of the heterostructure. In the map, regions with lower transmission are depicted in blue, whereas increasing transmission values are represented by a gradual transition toward red tones.

The position of the TIS within the bandgap shows a moderate dependence on the cap layer porosity. TISs near the midgap display high transmission with sharp peaks, while their transmission decreases and the peaks broaden as they approach the bulk band edges. At certain porosity values, two TISs can be observed.

Similarly, Fig. 5 presents the transmission map of the TISs as a function of the cap layer thickness, calculated at normal incidence for a representative porosity of p = 55%.

The position of the TIS within the bandgap strongly depends on the cap layer thickness for a porosity of 55% and a sample RI of ns=1.33. Changes in thickness around dcap=0.45d cover the entire bandga In fact, the transmission exhibits an almost periodic pattern with a period of approximately 0.47d for the chosen parametric structure.

For the typical values of p = 55% and dcap=d, we now examine the effect of increasing the number of periods N on the transmission spectrum of the TPhC. As shown in Fig. 6(a), the resonance peaks become significantly narrower as N increases from 3 to 15, with narrower peaks corresponding to higher N values. This narrowing reflects a decrease in the full width at half maximum of the peaks. While a higher number of layers sharpens the peaks, which is beneficial for sensing performance, it also reduces the peak intensity, which is undesirable. In Fig. 6(b), the quality factors and peak intensities are plotted together to illustrate this behavior Fig. 7.

(a) Transmission spectra of the TPhC at normal incidence for different numbers of periods N, showing that the peaks become narrower as N increases, using the same parameters as in the previous figures. (b) Quality factors and the corresponding peak values plotted as a function of the number of periods.

The quality factor of the TISs can reach values on the order of millions; however, for more than eleven periods, the peak intensities decrease markedly. It can be observed that the increase of one parameter is accompanied by the reduction of another important factor. Therefore, in this work, the number of layers in the calculations was fixed at six. Although choosing a value such as eleven could yield better results, our focus here is not on finding the optimal numbers.

To gain deeper insight into the behavior of the supported TISs, we present the corresponding electric field profiles within the porous cap layer for a thickness of dcap=2d, a porosity of 55%, and a sample RI of 1.33.

The absolute value profiles of the electric field for the TIS at \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{c}\text{a}\text{p}}=2\) and \(\:{\uplambda\:}=1535\:\text{n}\text{m}\) are shown for a porous cap layer with 55% porosity and a sample RI of ns=1.33. The upper panel displays the corresponding profiles obtained from COMSOL, while the lower panel presents the TIS profile derived using TMM. The vertical dotted lines mark the interfaces between the photonic crystals and the air, as well as the region of the cap layer, with the white area representing the air medium.

The results were obtained using both the Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) and the Finite Element Method (FEM) in COMSOL Multiphysics, with the two sets of simulations showing excellent agreement. The TIS exhibits a uniform field distribution across the cap layer, a characteristic that is particularly advantageous for sensing applications.

Our attention now turns to the sensing characteristics of the proposed porous structure, following an analysis of the structural effects on the TISs. Figure 8 illustrates the sensitivity factor of the structure as a function of the thickness of the porous silicon capp layer, assuming a porosity of 55% and using a representative RI of 1.33 for the sample.

It is observed that the sensitivity increases as the thickness of the cap layer decreases, which is expected due to the larger effective sample volume. The enhancement tends to saturate for thicknesses above dcap=11d. It should also be noted that at certain thicknesses, no sensitivity is observed, resulting in gaps, because the structure does not support TISs at those thicknesses.

Since the sample volume plays a significant role in the sensing process, the sensitivity is analyzed as a function of porosity. In Fig. 9, the sensitivity is plotted versus the porosity values for a sample RI of 1.33.

The sensitivity increases almost uniformly with porosity for a sample RI of 1.33, ranging from zero at a porosity of 0% to 910 at 100% porosity—that is, for a cap layer consisting of a single defect layer with a RI of 1.33. This represents a remarkably high value compared to previously reported works27.

We now attempt to evaluate the sensitivity values for other samples with different refractive indices. For this purpose, in Fig. 10, the sensitivity is plotted as a function of the RI of sample for a high porosity of 85%, which essentially provides the dynamic range of the sensor.

It is observed that, fortunately, the proposed sensor provides an almost constant sensitivity over a wide range of analytes, which is its most important characteristic, since most reported sensors are limited to a narrow operational range19,21. For comparison with previous studies, we now apply the proposed sensor to glucose sensing, and the corresponding results are presented in Fig. 11. The linear relationship connecting glucose concentration to the corresponding RI is expressed as17,42: ns=0.00011889×Cg + 1.33230545 where ns represents the RI of an aqueous sample at a given glucose concentration, and Cg denotes the glucose concentration in the solution (gL− 1).

It is quite interesting that this figure is plotted for a wide concentration range of glucose up to 36 g/L, and across this entire range the sensitivity, figure of merit, and detection limit remain nearly constant at approximately 803 (nm/RIU), 6.5 × 106, and 1.4 × 10− 7(RIU), respectively. These values are significantly higher than those reported in previous works43,44,45,46. The structural parameters of the cap layer are the same as those considered in the two preceding figures.

Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of the results obtained from our proposed biosensors with those reported in previous studies.

It is observed that our proposed sensor demonstrates superior performance across all indicators, even though the primary aim of this work was not to optimize the structure for achieving the highest possible values. For instance, when the porosity of the cap layer is taken as complete and the RI is set to 1.33, the calculated sensitivity reaches a value of 941. It should be noted that our results remain valid even for refractive indices up to 1.7. However, since our structure is based on the presence of aqueous materials within the porous medium, we have reported values only up to 1.44. None of the previous studies provide such a wide dynamic range while simultaneously maintaining superior sensing characteristics across all key factors, which highlights the high quality of the proposed structure.

Conclusion

In this work, a refractive index sensor based on topological modes in photonic crystals was proposed. The structure consists of a porous cap layer placed at the interface of two one-dimensional photonic crystals supporting topological interface modes. The porous nature of the cap layer makes the sensor suitable for aqueous and biological analytes. The sensing properties of the proposed structure were analyzed as a function of its structural parameters, demonstrating excellent performance across a wide dynamic range of analytes. For instance, within the RI range of 1.33–1.43, the sensor exhibits an almost constant sensitivity of about 745 nm/RIU. It was shown that the sensitivity of the sensor increases with the degree of porosity. Although the structure was not optimized to maximize performance, it was found that under complete porosity—where the analyte effectively acts as the defect layer—the sensitivity can reach 941 nm/RIU. As a case study, the structure was tested for glucose sensing and compared with previously reported works. The results show that for concentrations up to 36 g/L and at a porosity of 85%, the sensitivity, figure of merit, and limit of detection reach values of 803 (nm/RIU), 6.5 × 106, and 1.4 × 10− 7(RIU), respectively, outperforming earlier studies in all key metrics.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the analysis of current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljacic, M. Topological Photonics Nat. Photonics 8, 821, (2014).

Ozawa, T. et al. Topological Photonics Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 015006, (2019).

Lustig, E. & Segev, M. Topological photonics in synthetic dimensions. Adv. Opt. Photon. 13, 426 (2021).

Xiao, M., Zhang, Z. Q. & Chan, C. T. Surface impedance and bulk band geometric phases in one-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. X. 4, 021017 (2014).

Wang, Q., Xiao, M., Liu, H., Zhu, S. & Chan, C. T. Measurement of the Zak phase of photonic bands through the interface States of a metasurface/photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. B. 93 (R), 41415 (2016).

Palatnik, A., Sudzius, M., Meister, S. & Leo, K. One-dimensional Planar Topological Laser Nanophotonics 10, 2459, (2021).

Iwamoto, S., Ota, Y. & Arakawa, Y. Recent progress in topological waveguides and nanocavities in a semiconductor photonic crystal platform, opt. Mat. Express. 11, 319 (2021).

Haldane, F. D. M. & Raghu, S. Possible realization of directional optical waveguides in photonic crystals with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 013904 (2008).

Zhang, Z. et al. Dispersion tunable photonic topological wave-guides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 011701 (2022).

Tsurimaki, Y. et al. Topological engineering of interfacial optical Tamm States for highly sensitive near-singular-phase optical detection. ACS Photonics. 5, 929 (2018).

Lin, Y. C., Zhang, Y. Z., Cheng, S. H., Huang, C. Y. & Hsueh, W. J. Conjugated topological cavity-states in one-dimensional photonic systems and bio-sensing applications. Science 4, 106400 (2023).

Mortensen, N. A., Xiao, S. S. & Pedersen, J. Liquid-infiltrated photonic crystals: enhanced light-matter interactions for lab-on-a-chip applications. Microfluid Nanofluid. 4, 117 (2008).

Elshahat, S., Abood, M. S. M. E. I., Ouyang, Z. & Lu, C. One-dimensional topological photonic crystal mirror heterostructure for sensing, Nanomaterials 11, 2021. (1940).

Huang, J. et al. A novel glucose sensor based on MoS2 nanosheet functionalized with Ni nanoparticles. Electrochim. Acta. 136, 41 (2014).

Baghbadorani, H. K. & Barvestani, J. Sensing improvement of 1D photonic crystal sensors by hybridization of defect and Bloch surface modes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 537, 147730 (2021).

Kaviani, H. & Barvestani, J. Photonic crystal-based biosensor with the irregular defect for detection of blood plasma. Appl. Surf. Sci. 599 (599), 153743 (2022).

Elshahat, S., Mohamed, Z. E. A., Almokhtar, M. & Lu, C. High tunability and sensitivity of 1D topological photonic crystal heterostructure. J. Opt. 24, 035004 (2022).

Qing, Y. M., Ma, H. F., Wu, L. & Cui, T. J. Manipulating the light-matter interaction in a topological photonic crystal heterostructure. Opt. Express. 28, 34904 (2020).

Elshahat, S., Mohamed, Z. E. A., Abd-Elnaiem, A., Ouyang, Z. & Almokhtar, M. One dimensional topological photonic crystal for high-performance gas sensor. Micro Nanostruct. 172, 207447 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Multi-channel perfect absorber based on a one-dimensional topological photonic crystal heterostructure with graphene. Opt. Lett. 43, 4256 (2018).

Su, M. et al. Tamm-plasmon polariton biosensor based on one-dimensional topological photonic crystal. Results Phys. 48, 106454 (2023).

Su, M. et al. Polarization-independent and ultra-sensitive biosensor with a one-dimensional topological photonic crystal. Opt. Express. 30, 42415 (2022).

Haidar, O. et al. Enhancing Tamm plasmon sensor performance using nanostructured gold grating and porous materials. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 20452 (2024).

barghouti, M. E., Houari, F., Talbi, A., Mir, A. & Akjouj, A. Surface plasmon resonance sensors: temperature effects. Opt. Mater. 155, 115865 (2024).

Lamayny, K., Abouti, O. E., Amrani, M. & Boudouti, E. E. Surf. States One Dimensional grapheme-dielectric Photonic Cryst. Interact. 245, 356, (2024).

Rahmat, M. et al. Development of a novel Ozone gas sensor based on sol–gel fabricated photonic crystal. Sens. Actuators, A. 220, 53 (2014).

Zaky, Z. A., Alamri, S., Zhaketov, V. D. & Aly, A. H. Refractive index. Sens. Magnified Resonant signal. Sci. Rep. 12, 13777, (2022).

Çetinel, A. Characterization of octahedral Cu2O nanostructures grown on porous silicon by electrochemical deposition. Mater. Chem. Phys. 277, 125532 (2022).

Jenie, S. N. A. et al. Lanthanide luminescence enhancements in porous silicon resonant microcavities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 12012 (2014).

Arshavsky-Graham, S., Massad-Ivanir, N., Segal, E. & Weiss, S. Porous silicon-based photonic biosensors: current status and emerging applications. Anal. Chem. 91, 441 (2018).

Osminkina, L. A. and e. al., Antiviral adsorption activity of porous silicon nanoparticles against different pathogenic human viruses, Bioact. Mater. 7, 39, (2022).

Coffer, J. L. & Canham, L. T. Nanoporous silicon as a green, high-tech educational tool, Nanomaterials 11, 553, (2021).

Barvestani, J. Comprehensive and analytical investigation of topological interface States in one-dimensional photonic systems. Opt. Comm. 578, 131500 (2025).

http://refractiveindex.info.

Salem, M. S., Sailor, M. J., Harraz, F. A., Sakka, T. & Ogata, Y. H. Electrochemical stabilization of porous silicon multilayers for sensing various chemical compounds. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 083520 (2006).

Yariv, A. & Yeh Optical Waves in Crystals: Propagation and Control of Laser Radiation (Wiley, 1984).

Barvestani, J., Kalafi, M., Vala, A. S. & Namdar, A. Backward surface electromagnetic waves in semi-infinite one-dimensional photonic crystals containing left-handed materials. Phys. Rev. A. 77, 013805 (2008).

Barvestani, J. Analytical investigation of one-dimensional photonic crystals with a dielectric-superconducting pair defect. Opt. Comm. 284 (1), 231 (2011).

Mehrabi, M., Vala, A. S. & Barvestani, J. Localized photonic modes in photonic crystal heterostructures. Opt. Comm. 284, 5444 (2011).

Zhan, T., Shi, Y. D. X., Liu, X. & Zi, J. Transfer matrix method for optics in graphene layers. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 25 (21), 215301 (2013).

Ayyanar, N., Raja, G. T., Sharma, M. & Kumar, D. S. Photonic crystal fiber-based refractive index sensor for early detection of cancer. IEEE Sens. J. 18, 7093 (2018).

Lee, K., Babajanyan, A., Kim, C., Kim, S. & Friedman, B. Glucose aqueous solution sensing by a near-field microwave microprobe. Sens. Actuators A. 148, 28 (2008).

Abohassan, K. M., Ashour, H. S. & Abadla, M. M. Tunable wide Bandstop and narrow bandpass filters based on one-dimensional ternary photonic crystals comprising defects of silver nanoparticles in water. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 161, 110484 (2022).

Abohassan, K. M., Ashour, H. S. & Abadla, M. M. 1D photonic crystal-based sensor for detection of cancerous blood cells. Opt. Quantum Electron. 53, 1 (2021).

Sabsi, S. et al. Temperature sensor based on topological edge States in one-dimensional photonic crystals with a superconductor cavity. Opt. Comm. 591, 132180 (2025).

Mohamed, Z. A., Elshahat, S., Elnaiem, A. M. A. & Almokhtar, M. Sensing performance of Fano resonance induced by the coupling of two 1D topological photonic crystals. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 943 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by research project in the University of Tabriz titled as “The sensors based on photonic layered structures” with the number of 138.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All parts of the manuscript, including the research idea, computational work, result interpretation, and manuscript writing, were carried out by Jamal Barvestani.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barvestani, J. Topological interface state-based photonic crystal sensor with porous cap layer for high-performance biosensing. Sci Rep 15, 43675 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27526-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27526-4