Abstract

Herein, a useful model is developed for electrical conductivity of polymer nanocomposites integrating carbon black (CB) named as PCBs. The developed Kovacs model provides a clearer understanding of how key parameters such as interphase thickness (t), tunnel size (λ), network fraction and tunneling resistance (Rt) affect the conductivity of PCBs. Empirical results of many samples corroborate the precision and logical consistency of the refined model. The electrical conductivity of PCBs exhibits an inverse relationship with the radius of CB nanoparticles (R), percolation threshold, tunneling resistance and tunneling distance, underscoring the need to minimize these parameters to enhance the conductivity. Conversely, increasing some factors such as CB volume portion (φf), interphase thickness, and network fraction positively impacts the conductivity of PCBs. The highest amount of the smallest CB nanoparticles can provide the highest conductivity in PCBs. R = 5 nm and φf = 0.08 improve the PCB conductivity to 5 S/m. Nevertheless, R = 30 nm and φf = 0.01 cause an insulative sample. Also, the densest interphase (t = 20 nm) and the narrowest tunnels (λ = 1 nm) produce the superlative conductivity of 1.9 S/m at φf = 0.05, while t < 3 nm cannot enhance the PCB conductivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon black (CB) is produced from the incomplete combustion of organic materials, a process likely first observed in ancient times when black substances were deposited on objects near burning materials1,2,3,4,5. CB extensively modifies the stiffness, electrical conductivity, and physical properties of all polymeric materials such as elastomers, thermosets and thermoplastics6,7,8,9,10. CB nanoparticles range in size from 10 nm to 100 nm. Primarily, it was used as a reinforcing component in rubbers to enhance their toughness11,12. Polymer nanocomposites integrating CB (PCBs) can be utilized in antistatic and electrostatic discharge coatings, electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding, sensors, flexible and stretchable electronics, energy storage devices including batteries and supercapacitors, rapid prototyping technologies such as 3D printing, and in environmental applications including filtration and wastewater treatment13,14,15,16.

Incorporating CB into an insulating polymer matrix can achieve a high level of electrical conductivity for their nanocomposites17,18. For instance, Pokharel et al.17 studied the effect of CB on a polyurethane (PU) matrix for the formation of a conductive network. They found that the improvement in electrical properties is due to weak dispersion of CBs, which decrease the chain mobility. Toghchi et al.18 also used a composite of polyamide 66 (PA66) with CB to develop single-strand yarn for electromagnetic shielding applications, addressing the problem of textile products. Interestingly, its electrical conductivity was more than that of the PA66 composite. The presence of CB in the polymer matrix transforms it into an electrically conductive material.

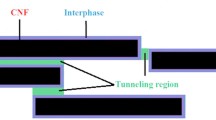

The interphase region is formed around nanoparticles in nanocomposites (Fig. 1), due to the strong surface bonding between the nanoparticle and the medium, besides the immense extent of filler surface area19,20,21,22,23. The interphase region can perform a network function in nanocomposites24,25,26. In fact, interphase regions can create percolation behavior in small volume fractions of CB in PCBs, reducing the onset of percolation and increasing electrical conductivity, but this is not mentioned in existing models for PCB conductivity.

A main mechanism leading to electron conductivity in nanocomposites is electron tunneling27,28. In this mechanism, electrons are transferred between two adjacent nanoparticles, leading to electrical conductivity throughout the system (Fig. 1)29. To increase electrical conductivity, the distance between CB nanoparticles must be very short. However, other obstacles, such as polymer resistance in the tunnels disrupts the growth of conductivity30,31. Tunneling resistance creates the big obstacle for electrical conductivity, which is explained in details in the developed model.

Although some models such as power-law have been used to estimate the conductivity of PCBs32,33,34,35, the existing models are incomplete, as they ignore the main terms such as interphase network and tunneling conductivity. The current article introduces a novel theoretical framework that improves the predictive capability of the Kovacs model36 for the conductivity of composite containing spherical CB nanoparticles. By incorporating formerly unnoticed terms such as interphase depth, tunnel size, and tunneling resistance, the refined model provides a comprehensive understanding of the key factors influencing the electrical conductivity. This methodology demonstrates a strong correlation with empirical data, confirming its validity and precision. This work not only offers more accurate estimations of critical parameters but also provides a detailed analysis of the structural and compositional elements on electrical conductivity. The advanced modeling techniques and analytical details presented in this study represent a notable advancement in the field, offering valuable insights and practical implications for the development and optimization of conductive PCBs.

Theoretical approaches

A sudden and substantial increase in PCB conductivity is noted when CB content touches the percolation onset37. At the percolation threshold, the PCB transitions from being an insulator to an electrical conductor. A smaller filler and thicker interphase reduce the percolation onset38, since they diminish the space among nanoparticles. Additionally, high interface tension enhances the contacts among nanoparticles decreasing the percolation onset39. The percolation threshold (vol%) in PCBs is obtained by a mathematical analysis as:

The variables R, t, γp, and γpf denote the radius of the CB, interphase thickness, polymer matrix surface tension and polymer - CB interface tension, respectively.

The polymer-filler surface tension can be estimated as follows39:

where γf denotes the filler surface tension. As Eq. (2) indicates, smaller differences between the surface energies of the filler and polymer result in better wetting of the filler by the polymer. This implies that a certain difference between the surface energies of the filler and polymer is desirable.

The interphase area that materializes around CB is of paramount significance in terms of electrical conductivity and percolation threshold. The interphase volume portion in PCBs can be estimated as40:

The CB volume fraction in PCBs is denoted as φf. The effectual volume portion of nanoparticles, considering the influence of the interphase can be expressed as:

After percolation onset, not all nanoparticles contribute to the electrical conductivity of PCBs, because only CB particles that successfully create the network can influence the conductivity. In this context, f denotes the percentage of CB particles that create the network. The percolation threshold and CB effectual volume portion are the only parameters that manage f as network percentage41 as:

By utilizing the f, one can ascertain the volume fraction of CB that resides within the network, as well as the interphase that has been established within the network. The volume fraction pertaining to tunneling regions is contingent upon the two aforementioned volume fractions. The volumetric portions of nanofiller (φN), interphase (φiN) and tunneling region (φtN) within the network are given by:

λ is the tunneling distance.

The model proposed by Kovacs et al.36. , pertaining to the composite electrical conductivity, as:

In this context, l, wf, RN, and Rt are indicative of filler length, filler weight fraction and the inherent resistances of nanofiller and tunnels, respectively. Furthermore, x serves as a coefficient. The Kovacs has reconciled 2x + 1 values ranging from 2.70 to 5.336. In another article, the variable x can oscillate between 0.0001 and 0.00138. This range is mutable, contingent on the morphology and nature of the nanoparticle. There exist other influential determinants such as interphase thickness, and resistance, which, although impactful, are not explicitly mentioned in the Kovacs model. In this innovative model, because the CB nanoparticle is spherical, we replace the length of the nanoparticle (Eq. 9) with the radius of CB. Since the denominator contains the square of the cross-sectional radius of CB, the radius of the CB present in the numerator gets canceled out with the cross-sectional radius.

Equation 9 is developed by the volume fraction of filler (φf) as:

The various types of resistances are elucidated below, accompanied by equations related to CB. The intrinsic resistance of the nanofiller is derived from Eq. (11). For spherical nanoparticles like CB, the effective region on resistance is S = πR2, as the cross-sectional area of the sphere is involved. Therefore42:

The tunneling region resistance (Rt) is constituted by the resistance of the nanoparticle (Rf) and the resistance of the polymer matrix (Rp) as:

However, the resistance attributed to the CB nanoparticle is so negligible that it can be omitted from computational considerations, due to the high conductivity of CB nanoparticles (104 S/m)43,44,45. Consequently, it is solely the intrinsic resistance of the polymer film that exerts an influence on the overall resistance of the tunneling region as:

In this context, ρ and S respectively signify the resistivity of the polymer layer and the contact area among CBs, in that order. Actually, Eq. 13 considers the main factors influencing the tunneling resistance and charge transferring through tunnels in PCBs.

There exists another case, termed as interphase resistance (Ri). Parameters influencing this resistance are CB radius (R), interphase thickness (t), and interphase conductivity (σi). Ri is obtained from:

The sum of all aforementioned resistances equates to the total resistance (RC) in the PCBs as:

In juxtaposition with all resistances delineated above, Rt exhibits paramount value. This is attributable to the fact that the resistance of the polymer film causes a direct correlation with tunnel resistance, thereby escalating its magnitude. Conversely, the resistances associated with CBs and interphases are markedly diminutive. This is due to the high conductivity of CB and interphase, being situated in the denominator, maintaining an inverse correlation with RN and Ri.

Upon determination and assessment of all significant factors and parameters, our next objective is to refine the initial Eq. (10). By Eq. (6) to (8), the effective volume fractions of different components are obtained. Also, Rt (Eq. 13) provides the final and dominant resistance. Now, Eq. 10 is systematically enhanced and developed by the mentioned terms as:

considering the concentrations of CB, interphase and tunnels in the network as well as the significant resistance of tunnels. Equation 16 is only usable for the PCBs containing the spherical CBs in the composites. It is considered that the CB nanoparticles are randomly dispersed in the nanocomposites, but the agglomeration of CBs can increase their contacts and expand the networks, which improve the conductivity of the nanocomposites46,47.

Results and discussion

Review of novel model by practical results

The proposed methodology demonstrates a high level of accuracy in forecasting both the conductivity of PCBs and the percolation threshold. This is evidenced by the alignment of percolation threshold values derived from Eq. (1) with laboratory data. This study incorporates four distinct samples: polystyrene (PS)/CB33, thermoplastic elastomer (TPE)/CB48, high-density polyethylene (HDPE)/CB49 and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF)/CB50, as seen in Table 1. Also, the properties of polymer matrices and CBs are mentioned in Table 1.

As revealed in Table 1, the measured percolation threshold of samples aligns well with the predictions of Eq. (1), suggesting that Eq. (1) is proficient in predicting the percolation threshold. Based on Eq. (1) and utilizing other data such as the interface tension, and CB size, the theoretical value of interphase thickness is determined. The surface energy, and density of CB, set at ~ 55 mN/m51,52, and ~ 1.8 g/cm3 in the current study. Table 1 reveals that the interphase thickness spans from 0.8 nm to 33 nm, which is logical at nanometer. Now, Eq. 16 is utilized to estimate the conductivity for PCB samples. Figure 2 shows the comparison among the empirical data and model productions for the samples. It is noticed that all predictions well follow the empirical data validating the model. Really, the suggested model is corroborated by the experimented conductivity of various examples.

Now, the tunneling properties can be calculated by the current methodology. As seen in Table 1, the tunneling distance changes from 0.5 nm to 2 nm. Also, ρ as tunneling resistivity of polymer is obtained from 45 ohm.m to 170 ohm.m. All these data are meaningful indicating the main role of tunneling mechanism in the PCB conductivity. The model also allows for the calculation of x power, which is found to be from 0.1 to 0.5 for the current samples. These data suggest that the theoretical values of x can control the electrical conductivity of PCB.

Impacts of factors on the PCB conductivity

The factors previously discussed have various impacts on the electrical conductivity of PCBs. In this section, we employ graphical analysis to investigate how each parameter can contribute to either a decrease or an increase in the conductivity. This exploration is conducted with a high level of rigor and specificity, suitable for a scholarly article. The graphs contain too applicable information for optimizing of conductivity in the CB-filled composites. These graphs provide more valuable information for the design and manufacturing of the optimized composites. Average factors are obtained from Table 1 and previously published articles53,54 as R = 20 nm, λ = 5 nm, t = 10 nm, φf = 0.05, ρ = 100 ohm.m, x = 0.1, γf = 55 mN/m, and γp = 35 mN/m. Also, the intrinsic conductivity of the polymer matrix is considered as about 0.

Figure 3 provides a clear representation for the powers of t and λ on the electrical conductivity of PCBs. As demonstrated, at t = 20 nm and λ = 1 nm, electrical conductivity of 1.9 S/m is attained. Conversely, t = 3 nm produces a decrease in electrical conductivity to 0 S/m. These observations suggest that thicker interphase layer and smaller tunneling distance enhance the electrical conductivity of PCBs. Nevertheless, very thin interphase cannot yield the charge transferring in the system.

The interphase engenders a thin layer encircling nanoparticles, thereby instigating the interaction of polymer chains with the particles22,55,56,57. This interaction precipitates the formation of a network even before nanoparticles collide with each other, thereby enhancing the electrical conductivity of PCBs, prior to their interconnection. This significantly contributes to the augmentation of the network density and expansion. If the communication between the polymer medium and nanoparticle is robust, it results in an increase in the interphase thickness. Conversely, if adhesion between the two phases is weak, interphase thickness diminishes58,59. Intrinsically, a growth in interphase depth attenuates the percolation inception (Eq. (1)) and enhances the operative filler portion, as a thicker interphase requires a lower amount of CB for the construction of the network. The proportion of CB present in the network (Eq. (5)) increases by a thicker interphase. Consequently, an upsurge in the interphase size leads to a large network, thereby enhancing the PCB conductivity.

As depicted in Fig. 3, tunneling distance clearly impacts electrical conductivity, and it is desirable for λ to be small. In PCBs, electrical conductivity is generated by the transfer of electrons via the tunneling mechanism. The conductive paths formed for electrical conductivity in PCBs is highly dependent on the distance between nanoparticles. If the distance between CBs is too large and exceeds the critical limit, electrons cannot be transferred to neighboring CBs, no conductive network is formed, and the PCB is not electrically conductive and behaves as an insulator. However, if the distance between CB nanoparticles is small and does not exceed the critical limit, electric charge is easily transferred between CB nanoparticles and a conductive network is formed causing the PCBs to be conductive30. Therefore, the distance between two CB particles is of significant importance, which naturally diminishes with an increase in the volume fraction of CB. So, the presented model accurately demonstrates this behavior and logics in relation to λ.

In the graphical elucidation presented in Fig. 4, the roles of R and φf are expounded. Each of these parameters knowingly influences the electrical conductivity. Within specific domain where R = 30 nm and φf = 0.01, PCBs demonstrate electrical conductivity of zero. However, the conductivity enhancement reaches its apex, denoted as 5 S/m, when R = 5 nm, and φf = 0.08. Hence, to reach pinnacle of electrical conductivity, it is essential to decrease the value of R and increase the extent of CB concentration.

The radius of carbon black (CB) plays a crucial role in determining the percolation threshold, which marks the transition from an insulating to a conductive state60. A reduction in CB radius not only increases the total number of particles per unit volume but also significantly enhances the specific surface area, thereby increasing the number of potential contact sites between neighboring fillers. These additional contacts reduce the average tunneling distance that provides more electron tunneling. As the tunneling resistance decreases exponentially with decreasing distance, smaller CB particles provide more efficient electron transport channels, which explains the marked improvement in conductivity for lower R values. Furthermore, a smaller CB radius effectively promotes the formation of localized agglomerates that facilitate percolation at lower filler loadings. In contrast, larger CB particles are fewer in number and are separated by wider polymer regions, which interrupt the electron transport paths and raises the percolation onset. Hence, finer CBs contribute to a denser and more continuous conductive network, validating the trend predicted by the model.

Increasing the CB concentration (φf) enhances the interphase volume fraction (φi) and the fraction of fillers within the conductive network (f), as described by Eqs. (3)–(5). Physically, this corresponds to a higher probability of particle–particle contacts and electron tunneling, allowing the formation of an extensive conductive cluster. Once the CB concentration exceeds the percolation threshold, these interconnected clusters span the entire composite, transforming the matrix from an insulating to a conductive material. Below this threshold, isolated CB domains act as discrete charge traps, contributing little to overall conduction. Therefore, the conductivity enhancement with increasing filler content arises from the combined effects of reduced tunneling distance, increased inter-particle connectivity, and network coalescence, which collectively govern electron mobility within the composite. This interpretation provides a physical foundation for the mathematical model and supports the trends predicted by the developed model.

The influences of the percolation threshold of CB (φp) and polymer tunneling resistance (ρ) on the electrical conductivity of PCBs, according to the proposed model, is illustrated in Fig. 5. When ρ = 190 ohm.m and φp = 0.1, electrical conductivity becomes exceedingly negligible, approximately 0.02 S/m. This leads to the conclusion that high values of ρ and φp exert a negative effect on electrical conductivity, which is not a desired outcome. In essence, to enhance the electrical conductivity in PCBs, both φp and ρ should be minimized. As observed in Fig. 5, when φp = 0.01 and ρ = 30 ohm.m, electrical conductivity reaches 0.5 S/m. Consequently, low extents of both φp and ρ are needed to optimize the PCB conductivity.

The percolation threshold is a key factor influencing electrical conductivity. It has an inverse relationship with electrical conductivity26,61,62,63, meaning that lower percolation thresholds enhance the electrical conductivity of PCBs, while higher ones reduce it. Ideally, the percolation threshold should be low, because a lower percolation threshold requires a smaller volume fraction of CB nanoparticles to form an electrically conductive network for electron transfer. As a result, more CB nanoparticles within PCBs are part of this network, which improves electrical conductivity. Conversely, a high percolation threshold negatively impacts electrical conductivity as it reduces the size and density of the network. This effect is accurately predicted by advanced model.

An increase in tunneling resistance results in decreased electrical conductivity. According to Eq. (13), polymer tunneling resistance directly affects the tunneling resistance. Therefore, an increase in polymer tunneling resistance naturally leads to a decrease in electrical conductivity, which is counterproductive to achieving high electrical conductivity. Increased resistance in the tunneling region due to higher polymer tunneling resistivity results in weaker charge transfer among CB nanoparticles. Conversely, a decrease in the resistance of the tunneling region leads to the acceleration of electron transfer within tunneling areas. This fact substantiates the model accuracy in predicting the effect of ρ on the PCB conductivity.

The parameters f and x can also induce changes in the electrical conductivity of PCBs, as illustrated in Fig. 6. An increased f = 0.9 and x = 0.1 cause the electrical conductivity of 0.35 S/m. On the other hand, a decrease in f and higher x significantly reduces electrical conductivity. At f < 0.2, the electrical conductivity is extremely weak, approximating to 0. These findings highlight that to achieve the desired electrical conductivity, it is crucial to determine the optimal values of f.

An increase in the f bolsters electrical conductivity. f indicates the proportion of CB within the network. A substantial f value signifies a noteworthy presence of CB network within PCBs. This proliferation of the network paves the way for the escalated transfer of electrons amidst CB nanoparticles, thereby augmenting electrical conductivity. On the other hand, a reduced f value implies the formation of tiny network, which obstructs electron transfer, making it challenging or even impossible. This results in the dispersion of CB and subsequent attenuation in electrical conductivity. The f straightly governs the density and dimensions of conductive network in the PCBs. It can thus be deduced that the proposed model offers the most precise predictions.

A low value of x is desirable for electrical conduction as it intensifies the networks of CB, tunneling region, and interphase in PCB. In contrast, a high x weakens the efficiency of these parameters, leading to a decrease in the electrical conductivity. However, the intrinsic nature of x needs more studies for optimization. Consequently, this model accurately describes the role of x in the PCB conductivity.

Figure 7 shows the impressions of γp and γf on the PCB conductivity. A reduction in γp coupled with an increase in γf results in high electrical conductivity of PCBs. This is evident that at γp < 24 mN/m and γf > 60 mN/m, the PCB has the conductivity of 0.17 S/m. However, when γp = 35 mN/m and γf = 45 mN/m, the PCBs shows the negligible conductivity of 0.04 S/m. To gain a higher conductivity, it necessitates to decrease the γp and increase the γf. Actually, higher difference between γp and γf can improve the conductivity in this sample.

The electrical conductivity behavior illustrated in this section can be physically explained by the influence of surface energy on the particle dispersion, agglomeration dynamics, and the resulting electron transport pathways in the PCBs. When the difference between the surface energies of the polymer (γp) and the filler (γf) increases, the interfacial tension at the polymer–filler boundary rises. A higher interfacial tension reduces the wettability of the CB nanoparticles by the polymer chains, which in turn promotes agglomeration and clustering of CBs rather than uniform dispersion. Although poor dispersion is generally undesirable for mechanical performance, in the context of electrical conductivity is beneficial, because the agglomerated CBs form dense conductive domains with shorter tunneling distances between adjacent particles64. These localized clusters improve the electron transport, facilitating the formation of continuous percolated networks across the matrix. In this way, higher interfacial tension fosters electronic conductivity through aggregation-driven contact points. Conversely, when γp and γf are similar (resulting in low interfacial tension), the polymer phase wets the CB particles effectively, leading to uniform dispersion and isolation of conductive fillers within the insulating polymer medium. The large separation between individual CBs increases the tunneling resistance and delays the formation of a conductive pathway, thereby raising the percolation threshold and lowering the composite’s conductivity. The enhancement in conductivity thus originates from a microstructural transition from isolated particles to a network of aggregated CB domains that provide multiple overlapping charge transport paths throughout the nanocomposite. This interpretation aligns with the proposed model and validates the observed dependence of PCB conductivity on the interfacial energy parameters.

Conclusions

A novel theoretical framework has been proposed to refine the Kovacs model for predicting electrical conductivity in PCBs. The enhanced Kovacs model has been validated through comparison with empirical results, demonstrating its capability to estimate the vital factors like interphase size, tunneling length, and polymer tunneling resistance. The conductivity of a system containing CB nanoparticles is enhanced by several key factors: a high amount and effectual concentration of CB, a low percolation threshold, a small radius of CB, a thick interphase, high interfacial tension, a short tunnel, and low polymer tunneling resistance. The highest conductivity for PCBs was found to be 5 S/m, reached with the smallest radius of CB (5 nm), and the highest amount of CB (φf = 0.08). However, the conductivity decreased to 0 S/m, by R = 30 nm and φf = 0.01. Additionally, the deepest interphase (t = 20 nm) and the shortest tunnels (λ = 1 nm) improve the conductivity to 1.9 S/m. Conversely, very thin interphase (t = 3 nm) produces an insulated sample. Also, at ρ = 190 ohm.m and φp = 0.1, the conductivity becomes exceedingly negligible, while the poorest ranges of φp = 0.01 and ρ = 30 ohm.m enhance the conductivity to 0.5 S/m. Furthermore, inferior surface tension for polymer with upper CB energy can increase the conduction in the PCBs, while high surface tension of polymer with low CB energy produce a poor conductivity. Also, more network fraction and lower x yield the higher conductivity. This study demonstrates that the electrical conductivity of the sample is primarily influenced by the size and the amount of the CB.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from corresponding author.

References

Barghamadi, M., Ghoreishy, M. H. R., Karrabi, M. & Naderi, G. Multiscale modeling of hyperviscoelastic behavior of particulate rubber composites based on hybrid silica/carbon black filler system. Polym. Compos. 45 (5), 4359–4373 (2024).

Elmaghraby, N. A. et al. Fabrication of carbon black nanoparticles from green algae and sugarcane Bagasse. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5542 (2024).

Laithong, T., Nampitch, T., Ourapeepon, P. & Phetyim, N. Quality improvement of recycled carbon black from waste tire pyrolysis for replacing carbon black N330. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 23726 (2025).

El-Khiyami, S. S., Ali, H., Ismail, A. & Hafez, R. Tunable physical properties and dye removal application of novel Chitosan polyethylene glycol and polypyrrole/carbon black films. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 20124 (2025).

Fernandez, M. G. C., Hakim, M. L., Alfarros, Z., Santos, G. N. C. & Muflikhun, M. A. Nanoengineered polyaniline/carbon black VXC 72 hybridized with woven Abaca for superior electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 14548 (2025).

Billotte, C., Romana, L., Flory, A., Kaliaguine, S. & Ruiz, E. Recycled from waste tires carbon black/high-density polyethylene composite: Multi‐scale mechanical properties and polymer aging. Polym. Compos. 45 (13), 11605–11618 (2024).

Haghgoo, M., Alidoust, A., Ansari, R., Jamali, J. & Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M. K. Breadth-first search algorithm on the finite element simulation of the electrical resistivity of the carbon black elastomeric pressurized sensor. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 187, 108523 (2024).

Tian, C. et al. Revealing the nanoscale reinforcing mechanism: how topological structure of carbon black clusters influence the mechanics of rubber. Compos. Sci. Technol. 258, 110847 (2024).

Dwivedi, P., Rathore, A. K., Srivastava, D. & Vijayakumar, R. Impact on mechanical and thermal characteristics of epoxy nanocomposites by waste derived carbon nanotubes, carbon black, and hybrid CNT/FCB reinforcing materials. Polym. Compos. 45 (13), 11701–11713 (2024).

Saberi, M., Moradi, A., Ansari, R., Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M. K. & Jamali, J. Developing an efficient analytical model for predicting the electrical conductivity of polymeric nanocomposites containing hybrid carbon nanotube/carbon black nanofillers. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 185, 108374 (2024).

Kumar, V. et al. Improved interfacial mechanical strength and synergy in properties of nano-carbon black reinforced rubber composites containing functionalized graphite nanoplatelets. Surf. Interfaces. 39, 102941 (2023).

Yuan, B., Zeng, F., Peng, C. & Wang, Y. Effects of silica/carbon black hybrid nanoparticles on the dynamic modulus of uncrosslinked cis-1, 4-polyisoprene rubber: Coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Polymer 238, 124400 (2022).

Díez-Pascual, A. M. Carbon-based Polymer Nanocomposites for high-performance Applications p. 872 (MDPI, 2020).

Jiang, D. et al. Electromagnetic interference shielding polymers and nanocomposites-a review. Polym. Rev. 59 (2), 280–337 (2019).

Chiu, S-H., Wicaksono, S. T., Chen, K-T., Chen, C-Y. & Pong, S-H. Mechanical and thermal properties of photopolymer/CB (carbon black) nanocomposite for rapid prototyping. Rapid Prototyp. J. 21 (3), 262–269 (2015).

Ayalew, A. A. Application of Polymer/Carbon Nanocomposite for Organic Wastewater Treatment. Polymer Technology in Dye-containing Wastewater: Volume 1: Springer; pp. 199–224. (2022).

Pokharel, P., Xiao, D., Erogbogbo, F. & Keles, O. A hierarchical approach for creating electrically conductive network structure in polyurethane nanocomposites using a hybrid of graphene nanoplatelets, carbon black and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 161, 169–182 (2019).

Toghchi, M. J. et al. Electrical conductivity enhancement of hybrid PA6, 6 composite containing multiwall carbon nanotube and carbon black for shielding effectiveness application in textiles. Synth. Met. 251, 75–84 (2019).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Assessment of electrical conductivity of polymer nanocomposites containing a deficient interphase around graphene nanosheet. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 8737 (2024).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Tensile modulus of polymer Halloysite nanotubes nanocomposites assuming stress transferring through an imperfect interphase. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 23219 (2024).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. A novel technique including two steps for modulus prediction in polymer Halloysite nanotube composites. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20511 (2024).

Doineau, E. et al. Multiscale analysis of hierarchical flax-epoxy biocomposites with nanostructured interphase by Xyloglucan and cellulose nanocrystals. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 184, 108270 (2024).

Soudmand, B. H., Biglari, H., Fotouhi, M., Seyedzavvar, M. & Choupani, N. A finite element approach for addressing the interphase modulus and size interdependency and its integration into micromechanical elastic modulus prediction in polystyrene/SiO2 nanocomposites. Polymer 309, 127463 (2024).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. A novel approach to predict the electrical conductivity of nanocomposites by a weak interphase around graphene network. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 21514 (2024).

Hadi, Z., Yeganeh, J. K., Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Predicting of electrical conductivity for Polymer-MXene nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28, 4229–4238 (2024).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Influences of defective interphase and contact region among nanosheets on the electrical conductivity of polymer graphene nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13210 (2024).

Hadi, Z., Yeganeh, J. K., Munir, M. T., Zare, Y. & Rhee, K. Y. An innovative model for electrical conductivity of MXene polymer nanocomposites by interphase and tunneling characteristics. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 186, 108422 (2024).

Zare, Y. & Rhee, K. Y. A simulation study for tunneling conductivity of carbon nanotubes (CNT) reinforced nanocomposites by the coefficient of conductivity transferring amongst nanoparticles and polymer medium. Results Phys. 17, 103091 (2020).

Dagar, S., Pathak, D., Oza, H. V. & Mylavarapu, S. V. Tunneling nanotubes and related structures: molecular mechanisms of formation and function. Biochem. J. 478 (22), 3977–3998 (2021).

Haghgoo, M., Ansari, R. & Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M. Predicting effective electrical resistivity and conductivity of carbon nanotube/carbon black-filled polymer matrix hybrid nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 161, 110444 (2022).

Mazaheri, M., Payandehpeyman, J. & Jamasb, S. Modeling of effective electrical conductivity and percolation behavior in conductive-polymer nanocomposites reinforced with spherical carbon black. Appl. Compos. Mater. :1–16. (2022).

Sohi, N., Bhadra, S. & Khastgir, D. The effect of different carbon fillers on the electrical conductivity of ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer-based composites and the applicability of different conductivity models. Carbon 49 (4), 1349–1361 (2011).

Motaghi, A., Hrymak, A. & Motlagh, G. H. Electrical conductivity and percolation threshold of hybrid carbon/polymer composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. ;132(13). (2015).

Qu, M., Nilsson, F. & Schubert, D. W. Novel definition of the synergistic effect between carbon nanotubes and carbon black for electrical conductivity. Nanotechnology 30 (24), 245703 (2019).

Shao, J., Liu, X. & Ji, M. Effect of interfacial properties of filled carbon black nanoparticles on the conductivity of nanocomposite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139 (6), 51604 (2022).

Kovacs, J. Z., Velagala, B. S., Schulte, K. & Bauhofer, W. Two percolation thresholds in carbon nanotube epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 67 (5), 922–928 (2007).

Payandehpeyman, J., Mazaheri, M., Zeraati, A. S., Jamasb, S. & Sundararaj, U. Physics-Based modeling and experimental study of conductivity and percolation threshold in carbon black polymer nanocomposites. Appl. Compos. Mater. 31 (1), 127–147 (2024).

Arjmandi, S. K., Khademzadeh Yeganeh, J., Zare, Y. & Rhee, K. Y. Development of Kovacs model for electrical conductivity of carbon nanofiber–polymer systems. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 7 (2023).

Taherian, R. Experimental and analytical model for the electrical conductivity of polymer-based nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 123, 17–31 (2016).

Ji, X. L., Jing, J. K., Jiang, W. & Jiang, B. Z. Tensile modulus of polymer nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 42 (5), 983–993 (2002).

Feng, C. & Jiang, L. Micromechanics modeling of the electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube (CNT)–polymer nanocomposites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 47, 143–149 (2013).

Badrul, F. et al. Preliminary investigation on the correlation between mechanical properties and conductivity of low-density polyethylene/carbon black (LDPE/CB) conductive polymer composite (CPC). Journal of Physics: Conference Series: IOP Publishing; p. 012020. (2022).

Neffati, R. & Brokken-Zijp, J. Electric conductivity in silicone-carbon black nanocomposites: percolation and variable range hopping on a fractal. Mater. Res. Express. 6 (12), 125058 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Microstructural modeling and simulation of a carbon Black-Based conductive polymer A template for the virtual design of a composite material. ACS Omega. 7 (33), 28820–28830 (2022).

Brunella, V., Rossatto, B. G., Mastropasqua, C., Cesano, F. & Scarano, D. Thermal/electrical properties and texture of carbon black PC polymer composites near the electrical percolation threshold. J. Compos. Sci. 5 (8), 212 (2021).

Haghgoo, M., Ansari, R. & Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M. K. The effect of nanoparticle conglomeration on the overall conductivity of nanocomposites. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 157, 103392 (2020).

Haghgoo, M., Ansari, R., Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M. K., Jang, S-H. & Nankali, M. Simulation of the role of agglomerations in the tunneling conductivity of polymer/carbon nanotube piezoresistive strain sensors. Compos. Sci. Technol. 243, 110242 (2023).

Dang, Z-M. et al. Complementary percolation characteristics of carbon fillers based electrically percolative thermoplastic elastomer composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 72 (1), 28–35 (2011).

Ren, D., Zheng, S., Huang, S., Liu, Z. & Yang, M. Effect of the carbon black structure on the stability and efficiency of the conductive network in polyethylene composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 129 (6), 3382–3389 (2013).

Ram, R., Soni, V. & Khastgir, D. Electrical and thermal conductivity of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)–Conducting carbon black (CCB) composites: validation of various theoretical models. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 185, 107748 (2020).

Badard, M., Combessis, A., Allais, A. & Flandin, L. Effect of viscosity and surface tension on dynamic percolation in liquid media. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 135 (24), 46313 (2018).

Merzouki, A. & Haddaoui, N. Electrical conductivity modeling of polypropylene composites filled with carbon black and acetylene black. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2012 (1), 493065 (2012).

Abdollahi, F. et al. A predictive model for electrical conductivity of polymer carbon black nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 46, 7491–7502 (2025).

Zare, Y., Naqvi, M., Rhee, K. Y. & Park, S-J. Advancing conductivity modeling: A unified framework for polymer carbon black nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 36, 26–33 (2025).

Farajifard, M., Yeganeh, J. K., Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Simulation of tensile strength for polymer hydroxyapatite nanocomposites by interphase and nanofiller dimensions. Polym. Compos. 45 (11), 10234–10245 (2024).

Mohammadpour-Haratbar, A., Boraei, S. B. A., Munir, M. T., Zare, Y. & Rhee, K. Y. A model for tensile strength of cellulose nanocrystals polymer nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 213, 118458 (2024).

Nematollahi, H., Mohammadi, M., Munir, M. T., Zare, Y. & Rhee, K. Y. Two-Step method for predicting young’s modulus of nanocomposites containing nanodiamond particles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 2343–2352 (2024).

Wang, J., Li, Y., Liu, H. & Tong, J. Surface tension, viscosity and electrical conductivity characteristics of new ether-functionalized ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 351, 118621 (2022).

Farajifard, M., Khademzadeh Yeganeh, J., Zare, Y., Munir, M. T. & Rhee, K. Y. Predicting the strength in hydroxyapatite-filled nanocomposites through advanced two‐phase modeling. Polym. Compos. 45 (18), 17121–17133 (2024).

Vieira, L. S. et al. A review concerning the main factors that interfere in the electrical percolation threshold content of polymeric antistatic packaging with carbon fillers as antistatic agent. Nano Select. 3 (2), 248–260 (2022).

Mazaheri, M., Payandehpeyman, J. & Khamehchi, M. A developed theoretical model for effective electrical conductivity and percolation behavior of polymer-graphene nanocomposites with various exfoliated filleted nanoplatelets. Carbon 169, 264–275 (2020).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T., Rhee, K. Y. & Park, S-J. Multi-scale prediction of effective conductivity for carbon nanofiber polymer composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 8895–8902 (2024).

Zare, Y., Munir, M. T., Rhee, K. Y. & Park, S-J. Effects of a deficient interface, tunneling size and interphase depth on the percolation inception, percentage of graphene in the Nets and conductivity of nanocomposites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 142, 110791 (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. Preparation of conductive polylactic acid/high density polyethylene/carbon black composites with low percolation threshold by locating the carbon black at the interface of co-continuous blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138 (17), 50291 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A., M.M. and Y.Z. prepared the paper. M.N., K.Y.R. and S-J.P. revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdollahi, F., Mohammadi, M., Zare, Y. et al. Unraveling of electrical conductivity for nanocomposites containing carbon black: a new insight into tunneling resistance. Sci Rep 15, 43554 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27527-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27527-3