Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a high risk factor for depression and anxiety in adulthood and are associated with the alterations in the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal (HPA) axis and monoamine neurotransmitters. This study aimed to elucidate the behavioral, neuroendocrine, and neural circuit mechanisms underlying the impact of ACEs effect on adult second-hit stress. We employed a “two-hit” mouse model that combines maternal separation (MS) with restraint stress (RS). To investigate the potential pathological effects of ACEs on depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in second-hit model mice. The mice were assessed through the behaviors test of sucrose preference test (SPT), tail suspension test (TST), open field test (OFT) and elevated zero maze (EZM). We analyzed the neural circuits in mice by immunohistochemical (IHC) technique, and detected the neuroendocrine changes of the HPA axis and monoamine neurotransmitters by ELISA, flow cytometry (FCM), and high performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD). Mice in the RS and MS + RS groups exhibited depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in the SPT, TST, OFT and EZM. Serum levels of GR, CORT, ACTH and CRH levels were decreased in the RS and MS + RS groups. Limbic‑system‑related neural circuits were activated in short- and long-term stress, with the expression of c-Fos decreasing and that of FosB increasing. Moreover, the concentrations of 5‑HT, dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and epinephrine (E) were lowered in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus. Maternal separation exerts a time-dependent dual effect on adult mice’s response to restraint stress: initially enhancing resilience, but later increasing susceptibility to depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors. These effects are likely mediated by neuroendocrine regulation of neural circuits involving HPA axis hormones and monoamine neurotransmitters. This study provides a novel two-hit mouse model for exploring how ACEs shape adult respond to stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression, a common mental disorder characterized by persistent low mood and loss of interest, is a leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide1.Its prevalence continues to rise annually2, and 62% of adults experiencing major depressive- episodes report at least one adverse childhood experience. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are also strongly associated with an increased lifetime risk of suicide3.The ACEs mainly include abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual), neglect (physical and emotional), and household dysfunction (parental divorce, domestic violence in the home, substance use disorders or mental illness experienced by a parent, and the incarceration of family members), and refers to negative events occurring during infancy, childhood, and adolescence (up to 18 years of age) that impact neurobehavioral development and many long-term health outcomes4. Compared with those with no ACEs exposure, individuals exposed to four or more ACE events have a 4- to 12-fold greater risk of depression, suicide attempts, and other health complications5.

Childhood represents a critical period for brain development. The harmful stress (e.g., ACEs) causes structural changes in developing brain regions (e.g., the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex), which may lead to potentially permanent consequences for essential functions such as regulating stress physiology, learning new skills, and developing adaptive capacities to future adversity6. Emerging research has identified specific components that link ACEs or other forms of ELS to subsequent mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, or post traumatic stress disorder), including cortisol signaling, inflammatory pathways, allostatic load (AL), DNA methylation, and telomere length7. AL is a core concept for measuring the degree of wear and tear caused by chronic stress and reflects the dysregulation of multiple physiological systems during prolonged adaptive responses8. It is utilized to study both the protective role of stress mediators during acute challenges and the detrimental effects of chronic harmful stress, offering insights into the biological consequences of ACEs9. ACEs may increase susceptibility to depression through the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal (HPA) axis response, 5-hydroxytryptaminergic function, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) deficits and immune inflammatory responses10, and they can further accelerate epigenetic aging, which is correlated with premature cellular senescence11.

Maternal separation (MS) is a primary model for simulating ELS and is designed to disrupt mother‒infant interactions and deprive developing offspring of critical sensory, nutritional, and emotional inputs12. It is widely used to investigate the biological mechanisms underlying ACE-induced depression and anxiety13.

The “two-hit hypothesis” of depression posits that an initial “first hit” (genetic or environmental insult) during early brain development increases vulnerability to psychiatric disorders, whereas a subsequent “second hit” in later life triggers individual-onset disease14,15. This hypothesis has been validated in rodent models16, with studies highlighting the pivotal role of the limbic system in mediating early-life adversity-attributable disorders17,18. Restraint stress (RS), a psychosocial stressor, causes the development of anxiety and depression19 and is a common stressor of second hit, which aligns with the “diathesis-stress” hypothesis20,21.

The “two-hit” model effectively recapitulates depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in individuals with ACEs following adult stress exposure22.This study builds a combined MS and RS model to elucidate the neuropathological mechanisms underlying the progression of depressive- and anxiety disorders in ACE-exposed individuals subjected to secondary stressors. By focusing on the effects of ACEs on anxiety and depression disorders caused by second hit in adults, the pathophysiological mechanisms behind the effects can provide new insights into the pathogenesis of ACEs and psychiatric disorders in later life.

Materials and methods

Animals

Forty female C57BL/6J mice and 10 male mice aged 8 weeks and weighing 20 ± 2 g were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (license no. SCXK (Beijing) 2021–0006). All the animals were raised in the clean-grade animal center of the Institute of Basic Theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, License No. SYXK (Beijing) 2021–0017. With free access to drinking water and food, the temperature (22 ± 2), humidity (45 ± 5%), and light/dark cycle alternated for 12 h/12 h.

Ethics and compliance

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.023 and the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals24.The animal experiments were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (Ethics No. IBTCMCACMS-21–2105-05).

Animal modeling and grouping

Maternal separation (MS).

When the animal weight increased to approximately 24 g, the female and male mice were mated to obtain pups (mixed at a ratio of 4:1). The pregnant mice were kept in a single cage before delivery, and the litters of the mice were maintained at 4 ~ 7 per cage. First, the dams were moved to a new cage, and then the pups were moved to the separation box and placed in the incubator at 32 °C for 8 h/day for 10 days (from postnatal days P5 to P14). After that, the pups remained with their mothers until P21 was weaned. The male pups were selected for the following experiments25,26.

Restraint stress (RS).

Male mice at 90 days of age (P90) were subjected to restraint stress. A pretreated 50 mL EP tube with holes for air was used as a binding device for 3 h/d27.

“Two-hit” mouse model (MS + RS).

Male mice were subjected to the maternal separation procedure, and restraint stress was continued at P90.

Animal Grouping.

There are ten groups in total, with 15 mice in each group. At P90, normal male mice were randomly divided into RS 0 d, RS 3 d, RS 7 d, RS 14 d and RS 21 d groups; male mice experienced maternal separation were randomly divided into MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d, MS + RS 7 d, MS + RS 14 d and MS + RS 21 d groups. All of them were equally subject to the corresponding number of days of restraint stress.

Behavioral testing

Behavioral tests were conducted after 3, 7, 14 and 21 days of restraint stress. The different behavioral tests were conducted at 9 a.m. every day for four consecutive days.

Sucrose preference test (SPT): Mice were pre-exposed to two bottles of 2% sucrose water for 24 h, then switched to one bottle of 2% sucrose water and one bottle of pure water for 12 h. After changing the bottle positions, the mice continued drinking for another 12 h to complete the sucrose solution adaptation period. Before the experiment began, the mice were fasted and deprived of water for 12 h.Mice were given one bottle of 2% sucrose water and one bottle of pure water that had been weighed. The test was conducted after 12 h, with the bottle being re-weighed again. The sucrose preference was calculated using the following formula: preference = (sucrose intake/total intake) × 100%28.

Tail suspension test (TST): The mouse was fixed on the suspension bar with 3 M medical tape at 1 cm from the tip of their tail, suspend its head downward and keep it 60 cm above the ground29. The time was counted for 6 min, and the immobility time of the mouse was recorded in the last 4 min.

Open-field test (OFT): After the mice adapted to the laboratory environment, they were placed at the center point of the open field box (40 cm×40 cm×35 cm), and the 20 × 20 cm area near the center point was set as the central zone. The total movement distance, the number of entries into the central area, and the dwell time in the central area in the first 5 min were recorded. Open field box was cleaned between mice to eliminate odors30. Behavioral data analysis was conducted using TopScan Version 2.0 software.

Elevated zero maze (EZM): The maze measures 65 cm in outer diameter, 60 cm in inner diameter, and 60 cm in height31, consisting of two opposite open arms and two closed arms. During experiments, mice were placed in the open arms facing the closed arms, allowed to move freely in a quiet environment for 5 min, and their dwell time, number of entries on the open arm and the closed arm, and total movement distance were recorded.

Animal procedures

Animals reaching humane endpoints (> 20% weight loss or severe dyspnea) were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg, 1% solution), followed by cervical dislocation. Anesthesia depth was confirmed by loss of pedal reflex (toe pinch) and corneal reflex. All procedures complied with the AVMA Guidelines for Euthanasia (2020 edition)32.

ELISA

The mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital, followed by blood collection. The plasma was collected from the EDTA anticoagulant tube and centrifuged. A mouse adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) ELISA kit (MEIMIAN, Jiangsu, China MM-0554M1), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) ELISA kit (MM-0509M1), corticosterone(CORT) ELISA kit (MM-0061M1) was used to detect the contents of hormones related to the HPA axis in plasma according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry (FCM)

The procedure described above was used to extract blood samples. The lymphoprep was added, the mixture was centrifuged, and the red blood cells were removed. The extracted white blood cells were isolated via a mouse PBMC separation kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China P2630), and then, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression was tested via a BriCyte E6 flow cytometer.

Immunohistochemistry

After anesthesia, the mice were perfused with 0.9% saline solution, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Thirty-micron-thick brain coronal sections were subjected to primary antibodies (c-Fos, 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; c-Fos, Recombinant Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody MA5-33035; FosB, 1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The cells were incubated with the Fos B (F-7) antibody sc-398595) overnight at 4 °C. Next, the sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit serum secondary antibodies and incubated with Vectastain Elite ABC reagent. Finally, 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate D5637-5G (DAB) was used for staining (Sigma‒Aldrich Corporation).

A Lecia Aperio VERSA Brightfield slide scanner was used for scanning, and the results were analyzed via Image 1.8.0 software.

High-performance liquid chromatography with an electrochemical detector (HPLC-ECD)

Mouse brains were dissected on ice, and specific brain nuclei were isolated with the assistance of a mouse brain atlas and a rodent brain matrix. Serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E) were detected in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hypothalamus.

The mobile phases were as follows: 90 mM sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 50 mM citric acid monohydrate, 1.7 mM sodium 1-octane sulfonate, 50 µM EDTA, and 10% acetonitrile. Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; sample size: 20 µL; Quatro S C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm); column temperature: 35 °C33.

10 statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard error. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was evaluated with the Levene test. If the data meet the assumptions of parametric testing (i.e., normal distribution and uniform variance), a two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the main effects and interactions of [Factor A, e.g., “treatment method”] and [Factor B, e.g., “time”]. Significant main effects or interactions were followed by Tukey’s post-hoc tests for pairwise comparisons. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical charts were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software.

Results

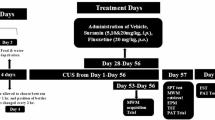

Animals experimental procedure and behavior tests. (A) Experimental temporal node flowchart for mouse modeling and behavioral testing. (B) The results of the SPT (n = 15) (C)The results of the TST (n = 15). Compared with the RS 0 d group *P < 0.05, compared with the MS + RS 0 d group #P < 0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P < 0.05.

The results of behavior tests. (A) Total distance traveled in OFT (n = 15). (B) The number of central zone entries in OFT (n = 15). (C) The time spent in the central zone in the OFT (n = 15). (D) Mouse movement locus in the OFT. (E) Total distance traveled in EZM (n = 15). (F) The number of open arms entries in the EZM (n = 15). (G) The time spent in the open arms in the EZM (n = 15). (H) Mouse movement locus in EZM. Compared with the RS 0 d group *P < 0.05, compared with the MS + RS 0 d group #P < 0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P < 0.05.

RS and MS + RS induced depressive– and anxiety-like behaviors in C57BL/6J mice

This study employed two-way ANOVA to investigate the independent effects (main effects) and interactions of RS and MS + RS on depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in mice at different times (0, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days) (Fig. 1A).

A significant interaction effect was observed in the SPF (interaction F (4, 139) = 3.433, P = 0.0104, row factor (time) F (4, 139) = 13.82, P < 0.0001, column factor (model) F (1, 139) = 15.69, P = 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d and MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d have the lowest sucrose preference (Fig. 1B, P = 0.006, P = 0.0003), RS 14 d (Fig. 1B, P = 0.0095, P = 0.0006) and RS 21 d (Fig. 1B, P = 0.0213, P = 0.0017) also have the lower sucrose preference ratio. There is a significant difference from the RS 3 d group, and the MS + RS 3 d group has the highest sucrose preference (Fig. 1B, P = 0.0004).

The two-way ANOVA of the TST data indicated a significant main effect of time and the modeling method and a non-significant interaction (interaction F (4, 136) = 1.418, P = 0.2313, row factor F (4, 136) = 2.935, P = 0.0230, column factor F (1, 136) = 15.37, P = 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d has the longest immobility time (Fig. 1C, P = 0.0009).

In OFT (Fig. 2D), the total distance traveled showed a significant main effect (interaction F (4, 136) = 11.95, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 136) = 1.365, P = 0.2495, column factor F (1, 136) = 0.2969, P = 0.5867). Compared with RS 0 d, the total distance movement of the RS 7 d, RS 14 d, and RS 21 d groups is significantly induced (Fig. 2A, P = 0.0007, P = 0.0026, P = 0.0029). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d, MS + RS 7 d, and MS + RS 21 d are reduced (Fig. 2A, P = 0.0091, P = 0.0154, P = 0.0008). The RS 0 d and MS + RS 0 d have a significant difference (Fig. 2A, P < 0.0001). The central zone entries of OFT have a significant main effect (interaction F (4, 129) = 10.94, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 129) = 1.251, P = 0.2929, column factor F (1, 129) = 17.88, P < 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, the number of entries into the central area of RS 3 d, RS 14 d, and RS 21 d is significantly increased (Fig. 2B, P = 0.0007, P = 0.0026, P = 0.0029). The time in the central zone of OFT has no significant difference (interaction F (4, 132) = 3.652, P = 0.0074, row factor F (4, 132) = 0.2335, P = 0.9191, column factor F (1, 132) = 2.788, P = 0.0973). There was no statistical difference in all groups (Fig. 2C).

Analysis revealed that in the EZM (Fig. 2H), the total distance traveled is significantly influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 129) = 12.88, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 129) = 7.303, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 129) = 0.07465, P = 0.7851). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 21 d has the longest move distance (Fig. 2E, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d and MS + RS 7 d have shorter move distance (Fig. 2E, P = 0.0262, P = 0.0371). There are significant difference between RS and MS + RS at 0 d and 21 d (Fig. 2E, P = 0.0002, P = 0.0003). In addition to a significant main effect of time, a significant interaction effect was also observed on open arm entries (interaction F (4, 137) = 9.686, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 137) = 4.441, P = 0.0021, column factor F (1, 137) = 0.1431, P = 0.7058). Compared with RS 0 d, open arm entries of RS 21 d were reduced (Fig. 2F, P < 0.0059). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 7 d and MS + RS 21 d have fewer entries (Fig. 2F, P = 0.0007, P = 0.0006). There are significant differences between RS and MS + RS at 0 d and 21 d (Fig. 2E, P = 0.0024, P = 0.0017). The open arm dwell time showed a significant main effect, with the modeling method being a key influencing factor (interaction F (4, 129) = 6.821, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 129) = 2.172, P = 0.0757, column factor F (1, 129) = 12.33, P = 0.0006). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 7 d and MS + RS 21 d spent less time in the open arm (Fig. 2G, P = 0.0007, P = 0.0163). Significant differences were observed between RS and MS + RS at 0 d and 3 d (Fig. 2G, P = 0.0009, P = 0.0479).

Monoamine neurotransmitter levels are reduced in crucial brain regions of the limbic system

The RS and MS + RS mice presented changes in 5-HT, DA, NE, and E in the cerebral limbic system. (A-D) The contents of NE, E DA and 5-HT in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hypothalamus, respectively, were measured in the RS and MS + RS groups (n = 8). Compared with the RS 0d group *P<0.05, compared with the MS+RS 0d group #P<0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P<0.05.

The NE content in the hippocampus (HIPP) was significantly affected by the time factor (interaction F (4, 70) = 1.612, P = 0.1808, row factor F (4, 70) = 21.78, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.4086, P = 0.5248). Compared with RS 0 d and MS + RS 0 d, RS 21 d and MS + RS 21 d have declined (Fig. 3A, P = 0.027, P < 0.0001). The analysis of E revealed significant main effects for both factors, along with a significant interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 18.69, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 110.7, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 24.12, P < 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d has risen (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0480), and RS 14 d and 21 d have declined (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0003, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d have reduced (Fig. 3B, P < 0.0001). The RS and MS + RS groups have significant differences at 0 d, 3 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 3B, P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0017, P = 0.0426). For DA, both main effects and their interaction were statistically significant (interaction F (4, 70) = 3.418, P = 0.0130, row factor F (4, 70) = 50.84, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 19.48, P < 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0004), and RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3C, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3C, P < 0.0001). There are significant differences between RS 14 d and MS + RS 14 d (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0115). For 5-HT, the interaction and the main effect of time were significant (interaction F (4, 70) = 5.478, P = 0.0007, row factor F (4, 70) = 23.61, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.6630, P = 0.4183) in HIPP. Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3D, P < 0.0001).

The NE content in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) was significantly regulated by the main effect of time as well as its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 5.187, P = 0.0010, row factor F (4, 70) = 43.91, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.5757, P = 0.4506). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d was raised (Fig. 3A, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d declined (Fig. 3A, P = 0.0021, P < 0.0001). For E, both main effects and their interaction were statistically significant (interaction F (4, 70) = 18.20, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 228.8, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 10.63, P = 0.0017). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d decreased (Fig. 3B, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0003), and MS + RS 14 d and 21 d declined (Fig. 3. B P < 0.0001). The RS and MS + RS groups have significant differences at 0 d, 3 d, and 21 d (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0004, P = 0.0003, P < 0.0001). For DA, the interaction and the main effect of time were significant (interaction F (4, 70) = 19.47, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 132.9, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 3.569, P = 0.0630). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0018), and RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3C, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0003), and MS + RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d declined (Fig. 3C, P < 0.0001). The RS and MS + RS groups have significant differences at 0 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0228, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0105). For 5-HT, both main effects and their interaction were statistically significant (interaction F (4, 70) = 2.961, P = 0.0255, row factor F (4, 70) = 70.70, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.01970, P = 0.8888). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3D, P = 0.0001), and RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3D, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d declined (Fig. 3D, P = 0.0317, P < 0.0001).

In the amygdala (AMY), NE content showed significant main effects and a significant interaction (interaction F (4, 70) = 3.797, P = 0.0075, row factor F (4, 70) = 53.99, P < 0.0001, column factor 1.426 F (1, 70) = 0.001039, P = 0.9744). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 14 d and 21 d have decreased (Fig. 3A, P = 0.0254, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d also decreased (Fig. 3A, P = 0.0003, P < 0.0001). The contents of E were significantly influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 13.28, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 114.9, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 3.118, P = 0.0818). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d have decreased (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0039, P = 0.0017, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d also decreased (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0001, P < 0.0001). There are significant differences between the RS and MS + RS groups at 0 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0425, P = 0.0019, P = 0.0001). For DA, significance was found for both the main effect of time and the interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 8.564, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 31.19, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.02164, P = 0.8835). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d have decreased (Fig. 3C, P < 0.0001). There is a significant difference between RS 14 d and MS + RS 14 d (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0103). Regarding 5-HT, a significant main effect of time as well as a significant interaction was observed (interaction F (4, 70) = 3.047, P = 0.0225, row factor F (4, 70) = 24.39, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.7748, P = 0.3817). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 21 d have decreased (Fig. 3D, P = 0.0152). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d has decreased (Fig. 3D, P < 0.0001).

In the hypothalamus (HYPO), NE content showed significant main effects of time and a significant interaction (interaction F (4, 70) = 3.565, P = 0.0105, row factor F (4, 70) = 26.47, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 3.064, P = 0.0844). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d increased (Fig. 3A, P = 0.0453), and RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3A, P = 0.0433). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d also has decreased (Fig. 3A, P < 0.0001). The contents of E were significantly influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 2.661, P = 0.0397, row factor F (4, 70) = 98.94, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.1966, P = 0.6589). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 14 d, and 21 d has decreased (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0011, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d also have decreased (Fig. 3B, P < 0.0001). For DA, a significant effect was found for both time and its interaction (interaction F (4, 70) = 3.254, P = 0.0166, row factor, F (4, 70) = 25.43, P < 0.0001, column factor, F (1, 70) = 3.220, P = 0.0771). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 21 d decreased (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0008). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d also have decreased (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0106, P < 0.0001). And 5-HT was significantly influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 70) = 7.520, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 70) = 81.13, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 70) = 0.009819, P = 0.9213). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 21 d has decreased (Fig. 3D, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d also have decreased (Fig. 3D, P < 0.0001).

The HPA axis was dysfunctional in RS and MS + RS mice

Variation in hormones regulated by the HPA axis in RS and MS + RS mice. (A) GR expression in peripheral blood leukocytes detected by FCM (n=6). (B) Light scatter plot of GR in white blood cells. (C) The contents of CRH, ACTH and CORT in the serum (n=6). Compared with the RS 0 d group *P<0.05, compared with the MS+RS 0 d group #P<0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P<0.05.

The GR of peripheral white blood cells (Fig. 4B) exhibited significant interaction and main effects (interaction F (4, 49) = 6.083, P = 0.0005, row factor F (4, 49) = 45.09, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 49) = 5.585, P = 0.0221). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 14 d decreased (Fig. 4A, P = 0.0007). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d, 14 d, and 21 d also have decreased (Fig. 4A, P = 0.0081, P < 0.0001). There is a significant difference between RS 21 d and MS + RS 21 d (Fig. 4A, P = 0.0016).

The CRH content in peripheral blood was also affected by both main effects and their interaction (interaction F (4, 50) = 4.426, P = 0.0039, row factor F (4, 50) = 6.770, P = 0.0002, column factor F (1, 50) = 5.414, P = 0.0241). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d and RS 7 d were raised (Fig. 4C, P = 0.0104, P = 0.0057). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 21 d increased (Fig. 4C, P = 0.0136). The contents of ACTH were significantly influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect (interaction F (4, 50) = 4.454, P = 0.0037, row factor, F (4, 50) = 19.29, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 50) = 3.182, P = 0.0805) in the serum. Compared with RS 0 d, RS 7 d was raised (Fig. 4C, P = 0.01). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d increased (Fig. 4C, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0026, P < 0.0001). The contents of CORT were also influenced by both the main effect of time and its interaction effect significantly (interaction F (4, 50) = 6.075, P = 0.0005, row factor F (4, 50) = 8.305, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 50) = 0.1370, P = 0.7129) in serum. Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 4C, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0004).

Different brain regions exhibit distinct Temporal responses to RS and MS + RS stress

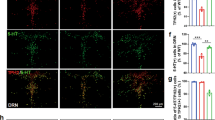

The expression of c-Fos changes in different brain areas. (A) Heatmap of c-Fos expression in different brain areas. (B) In the MS and MS + RS groups, c-Fos was expressed in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). (C) In the MS and MS + RS groups, c-Fos was expressed in the ventral pallidum (VP). (D) In the MS and MS + RS groups, c-Fos was expressed in the cingulate cortex (CC). (E) In the MS and MS + RS groups, c-Fos was expressed in the lateral septal nucleus (LSN). Compared with the RS 0 d group *P < 0.05, compared with the MS + RS 0 d group #P < 0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P < 0.05.

Changes in the expression of FosB in various brain areas. (A) Heatmap of FosB expressed in different brain areas. (B) In the MS and MS + RS groups, FosB was expressed in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), and the results of the IHC analysis of c-Fos (200 ×) are shown. (C) FosB was expressed in the lateral septal nucleus (LSN) in the MS and MS + RS groups. (D) FosB was expressed in the anterior amygdaloid area (AA) in the MS and MS + RS groups. (E) FosB was expressed in the amygdala (AMY) in the MS and MS + RS groups. Compared with the RS 0 d group *P < 0.05, compared with the MS + RS 0 d group #P < 0.05; at the same time point, the two groups were compared @P < 0.05.

An initial visual analysis of the data from all brain regions was conducted using heatmaps (Figs. 5A and 6A). Subsequently, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied separately to each brain region that showed marked expression differences. If a main effect or interaction was significant, Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post‑hoc test was employed for further multiple comparisons.

The expression of c-Fos in mPFC was significantly influenced by both main effects and its interaction (interaction F (4, 110) = 26.84, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 110) = 14.37, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 14.99, P = 0.0002). Compared with RS 0 d, the expression of c-Fos in RS 3 d and RS 7 d increased (Fig. 5B, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0007). There is a significant difference between RS 3 d and MS + RS 3 d (Fig. 5B, P < 0.0001). In VP, it also was affected by both main effects and its interaction (interaction F (4, 110) = 5.235, P = 0.0007, row factor F (4, 110) = 15.52, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 30.13, P < 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, the expression of c-Fos increased in RS 3 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 5C, P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0004). There are significant differences between RS 3 d, RS 14 d, MS + RS 3 d, and MS + RS 14 d (Fig. 5C, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0236). In CC, a significant main effect of time was observed (interaction F (4, 110) = 0.2035, P = 0.9360, row factor F (4, 110) = 12.38, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 0.04872, P = 0.8257). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d and 7 d increased (Fig. 5D, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0014). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, the expression of c-Fos increased in MS + RS 3 d and 7 d (Fig. 5D, P = 0.0019, P = 0.0037). In LSN (interaction F (4, 110) = 2.936, P = 0.0238, row factor F (4, 110) = 26.02, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 32.00, P < 0.0001). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d increased (Fig. 5). E P < 0.0001, P = 0.0278, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 3 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 5E, P = 0.0021, P = 0.001). The RS 3 d, 14 d, and MS + RS 3 d, 14 d have differences (Fig. 5E, P = 0.0081, P = 0.003).

The expression of FosB in NAc showed significant main effects and a significant interaction (interaction F (4, 110) = 2.577, P = 0.0414, row factor F (4, 110) = 22.76, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 4.972, P = 0.0278). Compared with RS 0 d, the expression of FosB increased in RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 6B, P = 0.0382, P < 0.0001, P = 0.042). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 6B, P = 0.0005, P = 0.0003). There is a significant difference between RS 21 d and MS + RS 21 d (Fig. 6B, P = 0.0382). In LSN, a significant effect was found for both time and its interaction (interaction F (4, 110) = 3.937, P = 0.0050, row factor F (4, 110) = 5.592, P = 0.0004, column factor F (1, 110) = 0.9667, P = 0.3277). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 14 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 6C, P = 0.0001, P = 0.0171). In AA, the expression of FosB was significantly influenced by both main effects and its interaction (interaction F (4, 110) = 7.229, P < 0.0001, row factor F (4, 110) = 42.71, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 9.135, P = 0.0031). Compared with RS 0 d, the expression of FosB increased in RS 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d (Fig. 6D, P = 0.0004, P = 0.001, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d increased (Fig. 6D, P < 0.0001). The RS and MS + RS groups have significant differences at 7 d and 21 d (Fig. 6D, P = 0.0015, P = 0.0246). In AMY, a significant main effect of time as well as interaction was observed (interaction F (4, 110) = 4.948, P = 0.0010, row factor F (4, 110) = 41.06, P < 0.0001, column factor F (1, 110) = 0.02072, P = 0.8858). Compared with RS 0 d, RS 14 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 6E, P < 0.0001). Compared with MS + RS 0 d, MS + RS 14 d and 21 d increased (Fig. 6E, P < 0.0001). There is a significant difference between RS 21 d and MS + RS 21 d (Fig. 6E, P = 0.0342).

Discussion

Depressive- and anxiety- like behaviors observed in the RS and MS+RS mouse groups are associated with alterations in monoamine neurotransmitter levels within the limbic system

We selected MS combined with RS to establish a two-hit model, which aligns with the “diathesis-stress” hypothesis. ACEs increase susceptibility to psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression. However, recent attention has focused on the potential positive impact of ACEs on resilience to stress in adulthood34. We observed the effects of early MS on the response to adult RS at different time points. The statistical results indicated that MS add RS modeling and RS separately induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in mice at different time points were different.

The study revealed that with time prolonged, both the MS + RS and RS groups of mice exhibited depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors, characterized by a decreased sucrose preference ratio and increased immobility time at 21d. Interestingly, the MS + RS showed the highest sucrose preference and the shortest immobility time at 3 days. Studies have shown that MS can reduce the sensitivity of C57 mice to depression when exposed to CSDS in adulthood35. This seems like a sign of resilience from depression or anxiety, “inoculation of stress“ hypothesis holds that early life stress induces the development of subsequent stress resistance36. Another report also confirmed the results37.

In OFT and EZM, with increasing RS duration, the initially active exploratory behavior of MS + RS 0 d group mice gradually shifted to anxiety-like behaviors, including reduced total movement distance and decreased number of entries into/duration spent in the central zone or open arms. Reports in the literature suggest that MS might exhibit higher anxiety levels38. Exposure to MS can also induce susceptibility to depressive–like behaviors in rodents39. This finding indicates a dual effect of MS (promoting resilience or increasing susceptibility), the outcome of which may depend on the duration of stress exposure. In the RS groups, with prolonged stress exposure, induces depressive–like to anxiety-like behaviors, the 7–14 days potentially being a critical time point. RS, as a psychosocial stressor, has been reported to interact with disease in ways influenced by the nature, number, and persistence of the stressor, as well as the individual’s biological vulnerability (e.g., genetic, constitutional factors), psychosocial resources, and learned coping patterns40. The behavioral changes in the RS groups exhibited a relatively smooth trend, as constitutive and repetitive stress often induces adaptation.

Most importantly, the behavioral test results indicate that exposure to a single stressor can induce anxiety- or depressive–like manifestations in mice in the short term while leading to adaptation or resistance states in the long term. MS exerts a protective effect against restress in adulthood in the short term but increases susceptibility to depression and anxiety in the long term. This differential effect may be related to factors such as the timing and intensity of the second stressor. The predictability of stress is also a significant factor influencing whether resilience or susceptibility develops41.

In another two-hit model study, a 5-HT/NE/DA triple-reuptake inhibitor was found to reduce susceptibility to depression in mice42. Monoamine neurotransmitters such as 5-HT, DA, and E are not only critically involved in mood regulation43 but also serve as indicators for evaluating depressive– and anxiety-like behaviors in mice44. Extensive research supports the significant role of dysfunction in the serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic systems in the neurobiology of depression and anxiety45,46,47, which is also implicated in ELS-induced mental disorders48,49,50.

This study revealed a comprehensive decrease in the contents of 5-HT, DA, NE, and E in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus of mice in both the RS and MS + RS groups, providing a clear explanation for the observed depressive– and anxiety-like behaviors. The curves of the RS groups exhibit a fluctuating pattern, and the MS + RS groups curve decreases slightly. Shortly after stress onset, the release of monoamines such as 5-HT, DA, and NE typically increases. This release is triggered either directly by brain circuits involved in assessing the stressful event or indirectly through activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Enhanced monoamine release poststress has been documented in the hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens51 Initially, this change serves to maintain monoaminergic system homeostasis. However, chronic stress (repetitive and/or prolonged stimulation) reduces monoamine neurotransmitter content, likely due to impaired neuroplasticity, persistent activation of the HPA axis, neuroinflammation, abnormal activation of neural circuits, and so on52,53.

ACEs exert lasting effects on amygdala function and structure, and the amygdala‒prefrontal cortex circuit may play a crucial role in the neurobiological etiology of emotional dysregulation in humans following ELS54. The hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex not only regulate emotion and cognition but also modulate the response to stress itself and are implicated in depression55. The involvement extends beyond the activity of multiple neurotransmitters within the limbic system; the responses of other chemicals and hormones (primarily glucocorticoids, GCs) also play key roles in the physiological mechanisms of the stress response56. The HPA axis serves as a necessary complement and effector system for the emotional functions of the monoamine system. Limbic structures, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus, are also involved in regulating the HPA axis57. Current research suggests that the body’s response to stress requires body–brain integration, which is consistent with our results.

Dysregulation of the HPA axis in the RS and MS+RS groups may constitute the biological basis underlying the dual effects of maternal separation

The HPA axis functions to adapt to challenges, regulating numerous bodily systems to help the organism cope with threats. The GR, which is primarily regulated by the HPA axis, is crucial for neuronal excitability, stress responsiveness, and behavioral adaptation. The initial stress signal prompts the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) to release CRH. CRH binds to CRH receptors in the anterior pituitary, stimulating the secretion of ACTH. ACTH then induces the adrenal cortex to secrete glucocorticoids (GCs). In humans, the primary GC is cortisol, whereas in rodents, it is predominantly CORT. Simultaneously, high levels of GCs can act on GRs in the hippocampus and pituitary gland, forming GC-GR complexes that reduce ACTH release, ultimately restoring GC secretion to homeostasis. This process constitutes the negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis.

Studies indicate that MS can disturb the programming of the HPA axis and exert lasting effects58. It has been reported that cumulative stress and ELS can lead to a blunted CORT response59. The expression level of GRs is relatively high, especially in the pituitary gland and hypothalamus, as well as various regions of the limbic system (including the amygdala, hippocampus and PFC), which are important for cognitive and psychological functions60.

Our findings demonstrated that in the MS + RS 7 d, 14 d and 21days, the CRH and ACTH levels remained persistently elevated, whereas the CORT and GR levels consistently decreased, with slight fluctuations observed on day 14. In the RS groups from days 7–14, decreases in the CORT, GR, CRH, and ACTH levels were detected, whereas from days 14–21, increases in the CORT, GR, CRH, and ACTH levels were detected. These findings indicate HPA axis dysfunction and dysregulated negative feedback regulation in the MS + RS group on day 7 and HPA axis hyperactivity with impaired negative feedback regulation in the RS group on day 14. This differential response might be due to MS damaging the sensitivity of the early development of the HPA axis, whereas repeated exposure to the same stressor induces habituation of the HPA axis response61. Substantial evidence confirms that stress in the early phases of development causes persistent alterations in the HPA axis to respond to stress in adulthood, a mechanism contributing to increased susceptibility to psychiatric disorders62. Critically, the observed alterations in monoamine neurotransmitters in brain regions and the changes in hormones in the peripheral HPA axis jointly constitute the neuroendocrine regulatory network, which is also the way in which the dual effects of MS are exerted.

Dual effects of maternal separation are associated with the fear circuitry within the brain’s limbic system

Major depressive- disorder (MDD) is increasingly viewed as a “circuitopathy“63. Neuroimaging studies have revealed abnormal functional connectivity within frontal‒limbic circuits—including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and limbic structures (amygdala)—in MDD patients64. The limbic system, encompassing the hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, and prefrontal cortex65, primarily mediates emotional perception, thought, and memory processes and is recognized as playing a crucial role in psychiatric disorders. To further explore the neural circuits responsive to MS, we utilized c-Fos and FosB labeling, focusing on the limbic circuitry.

c-Fos and FosB are members of the Fos family and are also markers of neuronal activity66. We analyzed the results of the IHC analysis of the c-Fos and FosB proteins in different brain areas and preliminarily filtered 19 brain regions. These include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), nucleus accumbens (NAc), ventral pallidum (VP), cingulate cortex (CC), lateral septum nucleus (LSN), medial septum nucleus (MSN), external globus pallidus (GPe), anterior amygdaloid area (AA), anterior hypothalamic region (AH), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), amygdala (AMY), periaqueductal gray (PAG), median raphe nucleus (MnR), dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), nucleus cuneatus (NCF), Hippocampus CA1 region (CA1), Hippocampus CA2 region (CA2), Hippocampus CA3 region (CA3), and Hippocampus DG region (DG) areas.

Our findings indicate that the number of brain regions containing c-Fos-positive cells increased with increasing RS duration, whereas the number of FosB-positive cells decreased. Furthermore, c-Fos appeared more sensitive to RS, whereas FosB was more responsive to MS. On the one hand, the activation of c-Fos and FosB is time dependent; acute stress increases c-Fos expression, whereas chronic stress elevates FosB expression. In support of this, studies have confirmed that stress activates distinct patterns of c-Fos and FosB protein expression in specific brain regions, patterns that are altered by repeated stress exposure67.

On the other hand, the mPFC, LSN, VP, CC, and MSN presented the most pronounced c-Fos effects, whereas the primary brain regions associated with the FosB effects were the AA, AMY, CA1, NAc, and LSN. On day 3 of RS, the highest numbers of c-Fos-positive cells were observed in the mPFC, LSN, VP, CC and MSN, with activation persisting for 21 days; by day 21 of MS + RS, the highest numbers of FosB-positive cells were found in the AA, AMY, CA1, and NAc, with stress-induced activation commencing from day 7. Limbic network regions (the mPFC, CC, VP, CA1, AMY, LSN, and MSN) were activated by both MS and RS, resulting in high c-Fos intensity in the prefrontal cortex, septal nuclei, cingulate cortex, and pallidum during short-term stress, whereas long-term stress led to increased FosB expression in the amygdala, hippocampus, septal nuclei, and nucleus accumbens. The ventral hippocampus → lateral septal nucleus → basolateral amygdala circuit is implicated in emotional empathy and fear extinction68, whereas the anterior cingulate circuit is involved in fear and safety assessment69. Another MS study in C57BL/6J mice revealed significantly increased c-Fos expression in numerous hypothalamic and limbic brain regions70.

The lateral septal nucleus (LSN), a highly interconnected hub region of the central brain whose activity modulates widespread circuits linked to anxiety and aggression regulation71, appears to be a core node within the neural circuitry underlying the dual effects of MS.

Additionally, the expression of c-Fos is transient and diminishes over time or with repeated stress, while FosB exhibits an accumulative pattern and persists for a longer duration. This results consistent with previous research72,73. On the basis of evidence that c-Fos reflects neuronal plasticity74 and that FosB may possess the capacity to modulate behaviors relevant to mood disorders75, this study demonstrated that the dual effects of MS are associated with brain fear-related circuitry. Anxiety behaviors arising from a lack of nutritional access and warmth during development76 may lower the safety assessment threshold, exerting long-lasting effects on neural circuit plasticity. This potentially confers self-protection during the initial phase of restress. However, sustained or excessive stress damages individual resilience (“plasticity imprinting”), ultimately leading to susceptibility to and the onset of psychiatric disorders.

Clinical implications of the “two-hit” mouse model and prospective intervention strategies

Preclinical experiments often use a two-hit model to study ELS. The results show that the various consequences of physiological and nonphysiological challenges that occur during the sensitive period of neural or immune development remain obvious in adulthood, especially after subsequent stressors. ELS is associated with two hypothetical pathways of psychopathology: innate immunity and the neuroendocrine system. The first hit is physiological, such as MS, and the second hit usually involves psychosocial stressors77. The two-hit model (MS + RS) employed in this study to assess how ACEs (MS) modulates an individual’s response to a subsequent stressor (RS) encountered in adulthood.

Our research analyzed the impact of ELS on the behavioral phenotypes related to anxiety and depression caused by stress events in adulthood and explained this process in terms of monoamine neurotransmitters and HPA axis hormones. Using c-Fos and FosB to label stressed brain regions, we attempted to identify the neural circuits that link the dual effects of MS to anxiety and depressive- behaviors. We found that the resilience of individuals with MS takes effect first, but as the duration or intensity of the stressor increases, their susceptibility to depression and anxiety increases78.

The latest systematic review and meta-analysis across 65 studies revealed that ACEs are common among children aged 18 or younger79 and that ACEs have always been associated with an increased risk of common mental disorders and suicidal tendencies80. Cross-sectional studies also revealed that ACEs are a risk factor for the burden of chronic diseases among middle-aged and elderly people in China81, and the economic burden of ACE-related health conditions for adults in the United States is substantial82.

Therefore, focusing on the prevention, early identification and precise intervention of ACEs are the key measures to mitigate their long-term impact. Antalarmin (a CRHR1 antagonist) and environmental enrichment therapy successfully restored early stress-induced PVI activity and cognitive deficits83. Lactobacillus plantarum strain PS128 can reduce depressive-like behaviors induced by ELS, normalize the HPA axis and the immune system, and regulate the levels of DA and 5-HT in the PFC84.

Neural circuits mediate social and environmental risks and resilience85. The human brain is plastic and has the inherent ability to restructure its structure and function throughout the lifespan86. ACEs are linked to negative impacts on health and development during early childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and later life, and early intervention in ACEs is highly efficient87.Therefore, early identification, screening and intervention for the development of ACEs are extremely urgent. The two-hit model can provide a time window sensitivity and multipathway (monoamine + HPA axis) strategic theory for the early intervention of ACEs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that maternal separation exerts a time-dependent dual effect on stress responses in adulthood. Short-term adaptive changes enhance resilience, whereas long-term alterations increase vulnerability to depression- and anxiety-like behaviors. The depression- and anxiety-like phenotypes induced in mice are accompanied by changes in limbic fear-circuit activity, neuroendocrine monoamine neurotransmitter levels, and HPA axis function.

The two-hit model may help delineate the critical period for neurodevelopmental interventions, although its clinical applicability requires further validation in translational studies.

Limitations of the present work include the exclusive use of male rodents and the lack of direct causal evidence. Future research should integrate multi‑omics data and perform cross‑species validation to link these findings with human ACEs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the policies and confidentiality agreements adhered to in our laboratory, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Anterior amygdaloid area

- AH:

-

Anterior hypothalamic area

- An:

-

Amygdaloid nucleus

- CA1:

-

Field CA1 of hippocampus

- CA2:

-

Field CA2 of hippocampus

- CA3:

-

Field CA3 of hippocampus

- Cg:

-

Cingulate cortex

- CnF:

-

Cuneiform nucleus

- DG:

-

Field DG of hippocampus

- DR:

-

Dorsal raphe nucleus

- MnR:

-

Median raphe nucleus

- MSN:

-

Medial septal nucleus

- LSN:

-

Lateral septal nucleus

- LGP:

-

Lateral globus pallidus

- mPFC:

-

Medial prefrontal cortex

- NAc:

-

Nucleus Accumbens

- PAG:

-

Periaqueductal gray

- PVN:

-

Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus

- VP:

-

Ventral pallidum

References

Lu, J. et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in china: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 8, 981–990 (2021).

Greenberg, P. et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the united States (2019). Adv. Ther. 40, 4460–4479 (2023).

O’Shields, J. D., Slavich, G. M. & Mowbray, O. Adverse childhood experiences, inflammation, and depression: evidence of sex- and stressor specific effects in a nationally representative longitudinal sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychol. Med. 55, e140 (2025).

Bath, K. G. Synthesizing views to understand sex differences in response to early life adversity. Trends Neurosci. 43, 300–310 (2020).

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258 (1998).

Shonkoff, J. P. et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics129 129, e232-246 (2012).

Dosanjh, L. H. et al. Five hypothesized biological mechanisms linking adverse childhood experiences with anxiety, depression, and PTSD: a scoping review. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 171, 106062 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Association between adverse experiences and longitudinal allostatic load changes with depression symptom trajectories in middle-aged and older adults in China. J. Affect. Disord. 372, 377–385 (2025).

Finlay, S. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and allostatic load: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 136, 104605 (2022).

Szymkowicz, S. M. et al. Biological factors influencing depression in later life: role of aging processes and treatment implications. Transl Psychiatry13 13, 160 (2023).

Klopack, E. T. et al. Accelerated epigenetic aging mediates link between adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms in older adults: results from the Health and Retirement Study. SSM Popul. Health17 17, 101071 (2022).

Birnie, M. T. & Baram, T. Z. The Evolving Neurobiology of early-life Stress, Neuron, Vol. 113, 1474–1490 (2025).

Cui, Y. et al. Early-life stress induces depression-like behavior and synaptic-plasticity changes in a maternal separation rat model: gender difference and metabolomics study. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 102 (2020).

Cao, P. et al. Early-life Inflammation Promotes Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence Via Microglial Engulfment of Dendritic Spines, Neuron, Vol. 109, 2573–2589 (2021).

Hill, R. A. et al. Sex-specific disruptions in spatial memory and anhedonia in a ‘two hit’ rat model correspond with alterations in hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and signaling. Hippocampus 24, 1197–1211 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Early maternal separation potentiates the impact of later social isolation in inducing depressive-like behavior via oxidative stress in adult rats. Psychopharmacology 242, 2503 (2025).

Gildawie, K. R. et al. Sex differences in prefrontal cortex microglia morphology: impact of a two-hit model of adversity throughout development. Neurosci. Lett. 738, 135381 (2020).

Worlein, J. M. Nonhuman primate models of depression: effects of early experience and stress. ILAR J. 55, 259–273 (2014).

Seo, J. S. et al. Cellular and molecular basis for stress-induced depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 22, 1440–1447 (2017).

Calcia, M. A. et al. Stress and neuroinflammation: a systematic review of the effects of stress on microglia and the implications for mental illness. Psychopharmacology 233, 1637–1650 (2016).

Monpays, C. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: determination of mitochondrial respiratory activity in a two-hit mouse model. J. Mol. Neurosci. 59, 440–451 (2016).

Deng, S. et al. Early-life stress contributes to depression-like behaviors in a two-hit mouse model. Behav. Brain Res. 452, 114563 (2023).

Percie du Sert. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000411 (2020).

National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory (Animals National Academies, 1996).

Mallaret, G. et al. Involvement of toll-like receptor 5 in mouse model of colonic hypersensitivity induced by neonatal maternal separation. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 3903–3916 (2022).

Orso, R. et al. Maternal behavior of the mouse dam toward pups: implications for maternal separation model of early life stress. Stress 21, 19–27 (2018).

Deng, Y. et al. Involvement of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in chronic restraint stress: disturbances of the kynurenine metabolic pathway in both the gut and brain. Gut Microbes. 13, 1–16 (2021).

Liu, M. Y. et al. Sucrose preference test for measurement of stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1686–1698 (2018).

Trunnell, E. R. et al. The need for guidance in antidepressant drug development: revisiting the role of the forced swim test and tail suspension test. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 151, 105666 (2024).

Hao, Y., Ge, H., Sun, M. & Gao, Y. Selecting an appropriate animal model of depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4827 (2019).

Tucker, L. B. & McCabe, J. T. Behavior of male and female C57BL/6J mice is more consistent with repeated trials in the elevated zero maze than in the elevated plus maze. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 13 (2017).

Leary, S. et al. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 (Edition American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020).

Guo, Y. X. et al. Loganin improves chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive-like behaviors and neurochemical dysfunction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 308, 116288 (2023).

Barrantes-Vidal, N. et al. Genetic susceptibility to the environment moderates the impact of childhood experiences on psychotic, depressive, and anxiety dimensions. Schizophr Bull. 51, S95–S106 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Maternal separation regulates sensitivity of stress-induced depression in mice by affecting hippocampal metabolism. Physiol. Behav. 279, 114530 (2024).

Parker, K. J., Buckmaster, C. L., Sundlass, K., Schatzberg, A. F. & Lyons, D. M. Maternal mediation, stress inoculation, and the development of neuroendocrine stress resistance in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 103, 3000–3005 (2006).

Calpe-López, C. et al. Brief maternal separation inoculates against the effects of social stress on depression-like behavior and cocaine reward in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 825522 (2022).

Cevik, O. S. et al. Maternal separation increased memory function and anxiety without effects of environmental enrichment in male rats. Behav. Brain Res. 441, 114280 (2023).

Ding, R. et al. Lateral Habenula IL–10 controls GABAA receptor trafficking and modulates depression susceptibility after maternal separation. Brain Behav. Immun. 122, 122–136 (2024).

Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G. & Siegel, S. D. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1, 607–628 (2005).

Shi, D. D. et al. Predictable maternal separation confers adult stress resilience via the medial prefrontal cortex Oxytocin signaling pathway in rats. Mol. Psychiatry. 26, 7296–7307 (2021).

Meng, P. et al. Epigenetic mechanism of 5-HT/NE/DA triple reuptake inhibitor on adult depression susceptibility in early stress mice. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 848251 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Monoamine neurotransmitters control basic emotions and affect major depressive disorders. Pharmaceuticals 15, 1203 (2022).

Jiang, N. et al. Antidepressant effects of parishin C in chronic social defeat stress-induced depressive mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 325, 117891 (2024).

Köhler, S. et al. The serotonergic system in the neurobiology of depression: relevance for novel antidepressants. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 13–22 (2016).

Liu, Y., Zhao, J. & Guo, W. Emotional roles of monoaminergic neurotransmitters in major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Front. Psychol. 9, 2201 (2018).

Ressler, K. J. & Nemeroff, C. B. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety12, 2–19 (2000).

Kim, S. et al. Early adverse experience and substance addiction: dopamine, oxytocin, and glucocorticoid pathways. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1394, 74–91 (2017).

Malave, L., van Dijk, M. T. & Anacker, C. Early life adversity shapes neural circuit function during sensitive postnatal developmental periods. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 306 (2022).

Sheppard, M. et al. Noradrenergic alterations associated with early life stress. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 164, 105832 (2024).

Joëls, M. & Baram, T. Z. The neuro-symphony of stress. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 459–466 (2009).

Flügge, G., Van Kampen, M. & Mijnster, M. J. Perturbations in brain monoamine systems during stress. Cell. Tissue Res. 315, 1–14 (2004).

Tripathi, S. J., Chakraborty, S. & Rao, B. S. S. Remediation of chronic immobilization stress-induced negative affective behaviors and altered metabolism of monoamines in the prefrontal cortex by inactivation of basolateral amygdala. Neurochem Int. 141, 104858 (2020).

VanTieghem, M. R. & Tottenham, N. Neurobiological programming of early life stress: functional development of amygdala-prefrontal circuitry and vulnerability for stress-related psychopathology. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 38, 117–136 (2018).

Lucassen, P. J. et al. Neuropathology of stress. Acta Neuropathol. 127, 109–135 (2024).

Mora, F. et al. Stress, neurotransmitters, corticosterone and body-brain integration. Brain Res. 1476, 71–85 (2012).

Herman, J. P., Ostrander, M. M., Mueller, N. K. & Figueiredo, H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry29, 1201–1213 (2005).

Thomas, J. C. et al. Social buffering of the maternal and infant HPA axes: mediation and moderation in the intergenerational transmission of adverse childhood experiences. Dev. Psychopathol. 30, 921–939 (2018).

Young, E. S. et al. Life stress and cortisol reactivity: an exploratory analysis of the effects of stress exposure across life on HPA-axis functioning. Dev. Psychopathol. 33, 301–312 (2021).

Cui, L. et al. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 30 (2024).

Herman, J. P. et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr. Physiol. 6, 603–621 (2016).

Juruena, M. F., Bourne, M., Young, A. H. & Cleare, A. J. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction by early life stress. Neurosci. Lett. 759, 136037 (2021).

Lu, J. et al. An entorhinal-visual cortical circuit regulates depression-like behaviors. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 3807–3820 (2022).

Bennett, M. R. The prefrontal-limbic network in depression: modulation by hypothalamus, basal ganglia and midbrain. Prog Neurobiol. 93, 468–487 (2011).

Kamali, A. et al. The Cortico-Limbo-Thalamo-Cortical circuits: an update to the original Papez circuit of the human limbic system. Brain Topogr. 36, 371–389 (2023).

Fóscolo, D. R. C. et al. Early maternal separation alters the activation of stress-responsive brain areas in adulthood. Neurosci. Lett. 771, 136464 (2022).

Perrotti, L. I. et al. Induction of DeltaFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J. Neurosci. 24, 10594–10602 (2004).

Peng, S. et al. Dual circuits originating from the ventral hippocampus independently facilitate affective empathy. Cell. Rep. 43, 114277 (2024).

Wu, K. et al. Distinct circuits in anterior cingulate cortex encode safety assessment and mediate flexibility of fear reactions. Neuron 111, 3650–3667 (2023).

Nishi, M. Effects of early-life stress on the brain and behaviors: implications of early maternal separation in rodents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7212 (2020).

Hunt, P. J. et al. Cotransmitting neurons in the lateral septal nucleus exhibit features of neurotransmitter switching. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 12, 390–398 (2022).

Engeln, M. et al. Selective inactivation of striatal FosB/∆FosB-expressing neurons alleviates L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Biol. Psychiatry. 79, 354–361 (2016).

Moellenhoff, E. et al. Effect of repetitive Icv injections of ANG II on c-Fos and AT(1)-receptor expression in the rat brain. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 280, R1095–1104 (2001).

Jaworski, J., Kalita, K. & Knapska, E. c-Fos and neuronal plasticity: the aftermath of kaczmarek’s theory. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 78, 287–296 (2018).

Ohnishi, Y. N. et al. FosB is essential for the enhancement of stress tolerance and antagonizes locomotor sensitization by ∆FosB. Biol. Psychiatry. 70, 487–495 (2011).

Trask, S., Kuczajda, M. T. & Ferrara, N. C. The lifetime impact of stress on fear regulation and cortical function. Neuropharmacology 224, 109367 (2023).

Kuhlman, K. R. Pitfalls and potential: translating the two-hit model of early life stress from preclinical nonhuman experiments to human samples. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 35, 100711 (2023).

Jaric, I. et al. Sex and estrous cycle effects on anxiety- and depression-related phenotypes in a two-hit developmental stress model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12, 74 (2019).

Madigan, S. et al. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in child population samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 179, 19–33 (2025).

Sahle, B. W. et al. The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 31, 1489–1499 (2022).

Lin, L. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and subsequent chronic diseases among middle-aged or older adults in China and associations with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. JAMA Netw. 4, e2130143 (2021).

Peterson, C. et al. Economic burden of health conditions associated with adverse childhood experiences among US adults. JAMA Netw. 6, e2346323 (2023).

Ma, Y. N. et al. Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons mediate CRHR1-dependent early-life stress-induced cognitive deficits in adolescent male mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 30, 2407–2426 (2025).

Liu, Y. W. et al. Psychotropic effects of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 in early life-stressed and naïve adult mice. Brain Res. 1631, 1–12 (2016).

Holz, N. E., Tost, H. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Resilience and the brain: a key role for regulatory circuits linked to social stress and support. Mol. Psychiatry. 25, 379–396 (2020).

Vaidya, N. et al. The impact of psychosocial adversity on brain and behavior: an overview of existing knowledge and directions for future research. Mol. Psychiatry. 29, 3245–3267 (2024).

Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and lifelong health. Nat. Med. 29, 1639–1648 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 82174251]; Beijing Natural Science Foundation [grant numbers 7232300]; the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Natural Science Foundation [Project Nos. 2024AAC03727]and the Autonomous Region health system research project [grant numbers 2024-NWZC-A010].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zihan Gong: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - Reviewing and Editing, Jingwen Yang: Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization, Ying Wang: Validation, Investigation, Methodology, Wenqing Liang : Validation, Investigation, Methodology, Shaohan Luo : Investigation, Xiang Li: Writing - Reviewing and Editing, Guangxin Yue : Conceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, Z., Yang, J., Wang, Y. et al. The double-edged sword effect of adverse childhood experiences forging adult stress into depression and anxiety. Sci Rep 15, 43632 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27535-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27535-3