Abstract

The rapid evolution of wireless communications toward 6G networks has intensified concerns about sustainability, as ultra-dense deployments of small-cell base stations demand unprecedented levels of energy. Meeting this demand with conventional grid power risks escalating operational costs and increasing the sector’s carbon footprint. To address this challenge, the present study develops a comprehensive mathematical modeling framework for bio-hybrid base stations powered by synthetic biology, with emphasis on microbial fuel cells and enzyme-mediated bioenergy harvesting. The framework quantifies energy demand, conversion efficiency, and associated carbon emissions under realistic operating conditions, while explicitly incorporating stochastic factors such as pH and temperature fluctuations, substrate saturation, and toxin-induced inhibition effects. Simulation results indicate that bio-hybrid systems can achieve reliable energy autonomy, significantly reducing reliance on centralized power grids while simultaneously lowering emissions. Importantly, modeling demonstrates how environmental variability can be mitigated through system-level design and hybrid storage integration, underscoring the resilience of such architectures. The main contribution of this work lies in bridging telecommunications engineering with synthetic biology through a unified, quantitative framework that evaluates feasibility, resilience, and sustainability. These insights establish a foundation for future experimental validation, field trials, and large-scale deployment of carbon-neutral 6G infrastructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid proliferation of wireless communication systems has positioned them as both a cornerstone of modern connectivity and a significant contributor to global energy consumption1. With over a billion user subscriptions and an electricity demand approximating 1% of the world’s total usage, these systems face escalating challenges as mobile data traffic grows exponentially. The increasing reliance on mobile technologies, cloud computing, and IoT devices has fueled an unprecedented demand for high-speed, low-latency, and always-available connectivity, placing enormous pressure on existing network infrastructure2. Prior studies on 5G and emerging 6G networks have identified escalating energy demands as a major barrier to sustainable deployment [Ref–Ref]. Renewable energy integration, including solar and wind, has been proposed for powering base stations, but these sources face well-known limitations such as intermittency, weather dependency, and storage inefficiency3. In parallel, bioenergy research has explored microbial fuel cells and enzyme-based systems as alternative power sources, demonstrating power densities up to 3 W/m² and cycle lives comparable to conventional storage4. However, most work remains at the laboratory scale, with limited focus on telecom integration. Synthetic biology efforts have highlighted the potential of engineered microbes for stable electron transfer, but practical system-level applications remain largely unexplored5. Despite these advances, no existing study has provided a unified mathematical framework to evaluate the feasibility, resilience, and sustainability of bio-hybrid power systems specifically for 6G networks. Addressing this gap, our paper develops and validates such a framework, bridging telecommunications engineering with synthetic biology and grounding feasibility claims in both simulation results and experimental benchmarks6. While significant advancements have been made in utilizing solar power, wind energy, and advanced battery storage systems to reduce dependency on fossil fuels, existing solutions remain constrained by factors such as intermittent energy generation, storage limitations, and high deployment costs. These challenges become even more pronounced as industry transitions toward sixth generation (6G) networks, where massive data traffic, ultra-reliable low-latency communication (URLLC), and seamless connectivity across heterogeneous environments will place unprecedented energy demands on telecommunications infrastructure7,8,9,10.

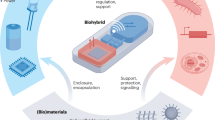

To address these challenges, researchers have begun exploring bio-inspired and bio-hybrid approaches as transformative paradigms for energy-efficient network design11. These methodologies draw inspiration from biological systems, leveraging nature’s inherent efficiency in resource management, self-organization, and adaptability qualities essential for the development of resilient, sustainable, and intelligent next-generation networks12. Bio-molecular communication models which mimic biological processes such as neural signaling, cellular communication, and metabolic pathways offer novel insights into ultra-low-power data transfer mechanisms13,14,15,16. Similarly, swarm intelligence, observed in insect colonies and other biological collectives, presents new strategies for self-organizing network topologies, enabling dynamic resource allocation, adaptive load balancing, and fault-tolerant communication architectures17. At the heart of bio-hybrid innovations lies synthetic biology, a rapidly evolving field that seeks to re-engineer biological systems to perform non-native functions, including energy harvesting, environmental sensing, and self-repair18. By integrating synthetic organisms with telecommunications infrastructure, bio-hybrid systems promise to revolutionize energy autonomy, allowing base stations to harness renewable biochemical energy sources. Among these approaches, microbial fuel cells (MFCs), photosynthesis-driven energy generation, and enzyme-catalyzed bioreactions offer viable alternatives to traditional battery- and grid-powered telecommunications networks19,20,21,22. By utilizing engineered microbial systems, base stations can convert organic substrates and environmental waste into electrical energy, thereby reducing dependence on centralized power grids while minimizing carbon footprints23. Additionally, self-repairing biofilms which can regenerate structural integrity in response to environmental degradation could significantly enhance the longevity, durability, and resilience of network hardware, lower maintenance costs and extending the operational lifespan of telecommunications infrastructure24.

The transition from 5G to 6G networks further underscores the critical need for such breakthroughs. While 5G has primarily focused on achieving higher speeds, increased bandwidth, and lower latency, 6G aims to embed intelligence, sustainability, and self-sufficiency at its core. The transition from 5G to 6G networks is expected to accelerate the deployment of ultra-dense small-cell infrastructures to support data-intensive applications such as immersive extended reality, holographic communications, and massive IoT connectivity. While these advances promise unprecedented levels of performance, they also introduce significant sustainability challenges. The energy demand of dense base station networks is projected to rise steeply, leading to increased operational costs and higher carbon emissions if powered primarily by conventional electricity grids. Existing strategies such as hardware efficiency improvements, network densification optimization, and demand-side management provide only incremental gains and are unlikely to fully offset the scale of anticipated energy consumption25,26.

Conventional renewable energy approaches, including solar and wind integration, have been proposed as alternatives to mitigate the growing energy footprint of mobile networks. However, these solutions remain constrained by intermittency, weather dependence, and the need for large-scale storage to ensure reliability. For small-cell base stations deployed in diverse and resource-limited environments, these limitations create barriers to autonomous and sustainable operation. Addressing these gaps requires novel solutions capable of providing continuous, localized, and resilient energy generation, motivating the exploration of bio-hybrid systems as a new paradigm for powering next-generation telecommunications27. The demand for high-performance, decentralized, and environmentally sustainable telecommunications will only intensify with the emergence of immersive technologies, such as holographic communications, tactile internet, brain-computer interfaces, and large-scale IoT applications28. These advancements require not only high computational efficiency but also robust, scalable, and self-sustaining energy sources, especially in remote, off-grid, or disaster-prone environments where traditional power grids are impractical. Bio-hybrid base stations, which operate independently through synthetic biology-enabled energy harvesting, present a revolutionary solution to this challenge29. By combining biological intelligence with telecommunications engineering, these systems bridge the gap between living and non-living technologies, fostering a new era of energy-autonomous, self-sustaining networks30. However, despite their immense potential, the integration of biological and electronic systems introduces unique challenges. Issues related to biocompatibility, biosecurity, ethical governance, and real-time adaptability must be carefully addressed. Additionally, the development of robust control algorithms will be essential for optimizing hybrid bio-electronic systems, ensuring they operate efficiently, securely, and sustainably in dynamic environments31.

As 6G network development accelerates, the convergence of synthetic biology and telecommunications will play a pivotal role in shaping the future of energy-efficient, adaptive, and environmentally responsible communication infrastructure32. This integration has the potential to fundamentally transform the telecommunications landscape, unlocking unprecedented levels of sustainability, resilience, and operational autonomy. By embracing bio-hybrid solutions, the industry can not only meet the growing demands of next-generation connectivity but also contribute to global efforts in building a greener, smarter, and more sustainable digital future33. The aim of this paper is to explore the design and optimization of bio-hybrid base stations for next-generation 6G networks, with a specific focus on leveraging synthetic biology to achieve energy autonomy. As the demand for high-speed, ultra-reliable, and sustainable communication networks continues to grow, traditional infrastructure faces increasing challenges, particularly regarding energy consumption, scalability, and environmental impact. The reliance on conventional power grids to support the mass deployment of SCBS has led to significant operational costs and carbon footprints, necessitating the development of alternative energy solutions. In response, this paper investigates how synthetic biology, a field that re-engineers’ biological systems for novel technological applications, can be harnessed to power and sustain bio-hybrid telecommunications infrastructure. To achieve this, we begin by critically analyzing the limitations of existing renewable energy solutions, such as solar and wind power, in supporting decentralized telecommunications infrastructure. While these technologies have made strides in reducing dependence on fossil fuels, they remain subject to intermittency issues, storage constraints, and spatial limitations, which hinder their seamless integration into next-generation networks. The growing demand for self-sustaining, decentralized base stations highlights the need for innovative approaches that can provide consistent, scalable, and adaptive energy sources.

Problem statement and research objectives

The transition to sixth generation (6G) wireless networks introduces unprecedented demands for energy efficiency, sustainability, and scalability. Current infrastructure, reliant on ultra-dense small-cell base station (SCBS) deployments, faces critical challenges due to its dependency on conventional power grids and non-renewable energy sources. Below, we expand the problem formulation to address technical, environmental, socio-economic, and ethical dimensions34.

The rapid expansion of 6G networks creates unprecedented energy demands that conventional renewable sources struggle to meet due to intermittency and scalability constraints. Bio-hybrid systems, powered by microbial and enzymatic energy conversion, offer a potential pathway toward self-sustaining, low-carbon telecommunications. However, several gaps remain unaddressed:

-

I.

How can the energy consumption of ultra-dense 6G small-cell base stations be mathematically modeled in relation to bio-hybrid energy harvesting capacity?

-

II.

What are the performance limits of microbial fuel cells and enzyme-driven systems when integrated into telecom infrastructure, particularly under fluctuating environmental conditions?

-

III.

How resilient and sustainable are bio-hybrid base stations compared to conventional energy sources, when evaluated in terms of outage probability, carbon footprint, and cost?

-

IV.

What socio-ethical considerations must be addressed to ensure responsible deployment of living systems in communication networks?

This paper addresses these questions by developing a mathematical modeling framework for bio-hybrid 6G base stations, validating its feasibility through simulation, benchmarking assumptions against experimental data, and discussing practical deployment challenges and solutions.

-

I.

Escalating energy demand and environmental impact

The energy consumption of 6G networks grows cubically with the number of connected devices \(\:{N}_{d}\:\)and data traffic \(\:\:\lambda\:\):

-

Carbon Footprint: Each SCBS emits \(\:{\text{CO}}_{2}=\alpha\:\cdot\:{E}_{\text{total}}\), where \(\:\alpha\:=0.5\hspace{0.17em}\text{kg\:}{\text{CO}}_{2}/\text{kWh}\). Global 6G deployment could contribute \(\:\:\ge\:2\backslash\:\%\:\) of annual carbon emissions.

-

Intermittent Renewables: Solar/wind supply \(\:S\left(t\right)\) follows stochastic profiles, risking outages:

where \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{weather}}\) is regional climate volatility.

-

II.

Technical limitations of bio-hybrid systems.

-

a.

Bio-energy harvesting efficiency.

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) and photosynthetic systems face bottlenecks:

- Substrate Utilization: Engineered microbes metabolize organic waste \(\:{S}_{\text{org}}\) with efficiency:

where \(\:{k}_{\text{cat}}\) (turnover rate) and \(\:{K}_{m}\) (affinity) are limited by genetic design.

-

Electron Transfer Losses: Extracellular electron transfer (EET) in electrogenic bacteria degrades with pH/temperature fluctuations:

-

III.

Biocompatibility and stability

-

Microbial survival: Engineered consortia in MFCs require optimal conditions:

Toxins from electronic components inhibit growth \(\:{K}_{i}\approx\:0.1\hspace{0.17em}\text{ppm}\).

-

Biofilm Durability: Self-repair kinetics depend on nutrient availability \(\:\left[N\right]\)

-

IV.

Socio-economic and deployment challenges

High \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) demands \(\:{{\uprho\:}}_{\text{SCBS}}\ge\:{10}^{3}\hspace{0.17em}{\text{nodes}\text{/}\text{km}}^{2},\)but space constraints limit bio-harvester placement.

Low \(\:\:{\uplambda\:}\:\)but limited grid access. Bio-hybrid systems must achieve levelized cost of energy (LCOE) \(\:\le\:0.10/\text{kWh}\:\):

where \(\:\:r\)is the discount rate and CapEx includes bioreactor installation.

Assumptions (base case)

CapEx = $170,000; OpEx = $12,000/year; discount rate r = 8%; lifetime T = 15T = 15 years; annual net deliverable energy E = 60,000 kWh.

Using the standard LCOE expression consistent with the manuscript:

The present-value annuity factor is\(\:AF=1-\left(1+r\right)-Tr=8.559AF=\frac{1-{\left(1+r\right)}^{-T}}{r}=8.559.\)\(\begin{aligned} Thus,PV\left( {energy} \right) & = E \cdot AF = 513,568.7 = E \cdot AF = 513,568.7kWh,PV\left( {\cos ts} \right) = CapEx + OpEx \cdot AF = 272,713.74 \\ & = CapEx + OpEx \cdot AF = 272,713.74. \\ \end{aligned} .\).

-

b.

Integration with legacy infrastructure.

Retrofitting 5G macro-cells with bio-hybrid SCBS requires:

-

Frequency coordination: Avoid interference between 5G (Sub-6 GHz) and 6G (THz) bands.

-

Energy sharing: Prioritize URLLC traffic via hybrid power allocation:

-

V.

Security and ethical risks.

-

Biotampering: Adversarial attacks could reprogram synthetic microbes to overproduce waste:

Where \(\:\:{\uptheta\:}\)represents genetic parameters.

-

Data-Biology Interface: Secure communication between biological and electronic components:

-

GMO regulations: Compliance with biosafety protocols limits deployable strains.

-

Ethical concerns: Public distrust of “living networks” necessitates transparency indices \(\:\:{\uptau\:}\):

-

VI.

Latency-reliability trade-offs in URLLC

Bio-hybrid systems must guarantee \(\:\text{Pr}\left(L>1\hspace{0.17em}\text{ms}\right)\le\:{10}^{-5}\) under energy constraints. For a network slice \(\:\:S\:\):

where \(\:{C}_{S}\) is slice capacity and \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{S}\:\) is service rate. Energy fluctuations induce queuing delays \(\:{Q}_{S}\propto\:\text{Var}\left({E}_{\text{bio}}\right)\).

Research objectives

The study pursues a multidisciplinary strategy to advance sustainable 6G networks through bio-hybrid innovations. (1) Genetic circuit optimization focuses on reprogramming microbial consortia using CRISPR-based metabolic engineering to enhance bioenergy harvesting efficiency beyond 30%, prioritizing robustness against environmental variability in organic waste and pH levels. (2) Hybrid energy storage integrates AI-driven algorithms to intelligently balance bio-supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries, optimizing for minimal system weight and cost while ensuring a cycle life exceeding 10,000 charge-discharge phases. (3) Ethical deployment frameworks employ region-specific surveys to quantify public acceptance, synthesizing weighted metric such as transparency (τ), energy cost (LCOE), and safety into a deployment score (δ) to guide equitable infrastructure rollout. (4) Socio-economic feasibility is rigorously evaluated by contrasting urban deployments, constrained by limited bioreactor space, against rural scenarios reliant on decentralized bio-energy solutions. (5) Security protocols address emerging cyber-biological risks, including adversarial manipulation of microbial pathways, ensuring metabolic stability and public trust in bio-augmented networks. Together, these objectives bridge synthetic biology, AI, and socio-technical governance to deliver scalable and ethically grounded 6G systems.

-

I.

Genetic circuit optimization: Engineer microbial consortia to achieve \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{bio}}\ge\:30\backslash\:\%\:\)via CRISPR-based metabolic pathway editing.

-

II.

Hybrid energy storage: Develop AI-driven buffers combining bio-supercapacitors \(\:{C}_{\text{bio}}\) and lithium-ion cells:

$$\:\text{min}\left(\text{Weight}\cdot\:{C}_{\text{bio}}+\text{Cost}\cdot\:{C}_{\text{Li}}\right)\hspace{1em}\text{s.t.}\hspace{1em}\text{Cycle\:Life}\ge\:{10}^{4}$$(14) -

III.

Ethical Deployment Frameworks: Quantify public acceptance via surveys and derive region-specific deployment scores \(\:\:{\updelta\:}\):

$$\:{\updelta\:}={w}_{1}\cdot\:{\uptau\:}+{w}_{2}\cdot\:\text{LCOE}+{w}_{3}\cdot\:\text{Safety}$$(15)

Modeling 6G ultra-dense network dynamics

The study holistically analyzes the interplay of energy, infrastructure, and socio-technical factors in ultra-dense 6G networks. Energy consumption dynamics are modeled by decomposing total demand into transmission, computation, cooling, and backhaul components, emphasizing how device density and AI-driven signal processing amplify thermal and operational inefficiencies35. Thermal management frameworks evaluate cooling system performance under fluctuating workloads, correlating heat dissipation with microbial bioenergy harvesting rates to ensure sustainable thermal regulation. Security and ethical risks are dynamically mapped, incorporating adversarial threats to bio-hybrid systems and public transparency metrics to mitigate distrust in genetically engineered energy solutions36.

Energy consumption model

The energy consumption model provides a comprehensive framework to quantify and optimize the operational power demands of 6G ultra-dense networks. Total energy demand is decomposed into four interdependent components: transmission energy from wireless signal propagation across densely deployed small-cell base stations (SCBS), computation energy for AI-driven network management and real-time signal processing, cooling energy to mitigate heat generated by electronic components, and backhaul energy for data routing via fiber-optic or microwave links. Transmission energy scales linearly with the number of connected devices and SCBS density, while computation energy is amplified by machine learning algorithms optimizing beamforming and resource allocation. Cooling efficiency directly impacts sustainability, as thermal dissipation from transmission and computation hardware necessitates energy-intensive climate control systems37.

The total energy demand of a 6G ultra-dense network can be broken into transmission, computation, cooling, and backhaul energy:

where:

-

\(\:{N}_{d}\) = number of connected devices.

-

\(\:{P}_{\text{Tx}}\) = transmission power of SCBS.

-

\(\:{P}_{\text{comp}}\) = computation power required for signal processing.

-

\(\:{Q}_{\text{thermal}}\)= heat generated by electronic components.

-

\(\:{\eta\:}_{\text{cool}}\) = cooling system efficiency \(\:\left(0\le\:\eta\:cool\le\:10\le\:{\eta\:}_{\text{cool}}\le\:1\right).\).

-

\(\in _{{backhaul}}\)= backhaul transmission loss factor.

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{fiber}}\) = energy required for fiber-optic backhaul.

The total carbon emissions associated with small-cell base station (SCBS) deployment are estimated by multiplying the network’s total energy consumption (\(\:{E}_{\text{total}}\)) by the carbon emission coefficient (α). This relationship is expressed mathematically

The parameter represents the carbon emission coefficient, which quantifies the amount of carbon dioxide released per unit of energy consumed. As shown in Eq. (18), a typical value is taken as

The overall energy consumption of an ultra-dense 6G network is obtained by summing the contributions from transmission, computation, cooling, and backhaul subsystems. This relationship is expressed in Eq. (19):

where:

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{Tx}}\) = Transmission energy (power used for wireless signal transmission).

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{comp}}\) = Computation energy (signal processing, AI-based network management).

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{cool}}\) = Cooling energy (for thermal regulation of SCBS).

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{backhaul}}\) = Backhaul energy (data transmission via fiber optic or wireless links).

Each component can be further expanded.

-

(i)

Transmission energy consumption.

The transmission energy consumption of small-cell base stations (SCBS) is calculated as the product of the number of SCBS, their operating time, and the transmission power per unit as shown in Eq. (20):

where:

-

NSCBSN\(\:{}_{\text{SCBS}}\) = Number of small-cell base stations.

-

T = Operational time (hours per year).

-

\(\:{P}_{\text{Tx}}\) = Average transmission power per SCBS (Watt).

-

(ii)

Computation energy consumption

The computational energy required for tasks such as signal processing and network optimization is determined by the number of small-cell base stations, their operational duration, and the computation power per unit. This relationship is given in Eq. (21):

where:

-

\(\:{P}_{\text{comp}}\) = Computation power per SCBS (Watt).

-

(iii)

Cooling energy consumption

The energy required for cooling small-cell base stations (SCBS) is determined by the amount of heat generated during operation and the efficiency of the cooling system as expressed in Eq. (22):

where:

-

\(\:{Q}_{\text{thermal}}\) = Waste heat generated by SCBS.

-

\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{cool}}\) = Cooling system efficiency (typically 0.3–0.5).

Since \(\:{Q}_{\text{thermal\:}}\)is largely proportional to transmission and computation power, we approximate:

Where is the heat dissipation coefficient.

-

(iv)

Backhaul energy consumption

The backhaul energy consumption of SCBS arises from data transmission over fiber-optic and microwave networks and is proportional to the energy required by the fiber component. This relationship is given in Eq. (24):

where:

-

\(\in _{{backhaul}}\) = Backhaul loss factor.

-

\(\:{E}_{\text{fiber}}\) = Fiber-optic power consumption per unit data.

Carbon emission estimation

The carbon footprint of 6G ultra-dense networks is quantified by correlating energy consumption with region-specific emission coefficients, translating operational power demands into environmental impact. Emissions are derived from the cumulative energy use of transmission, computation, cooling, and backhaul systems, with transmission and AI-driven processing identified as dominant contributors due to their dependency on energy-intensive hardware and cooling infrastructure38. Regional disparities in grid carbon intensity such as coal-dominated versus renewable-powered grids are integrated into tailor mitigation strategies, prioritizing bioenergy harvesting and hybrid storage in high-emission zones. The total carbon footprint from SCBS deployment is:

where:

-

\(\:{\upalpha\:}\) = Carbon emission coefficient (kg CO₂ per kWh).

Bioenergy harvesting model

The bioenergy harvesting model integrates microbial fuel cell (MFC) technology to sustainably power 6G networks by converting organic waste into electrical energy. System efficiency is governed by substrate utilization rates, electron transfer kinetics, and power circuit performance, with CRISPR-engineered microbial consortia optimizing metabolic pathways to enhance waste-to-energy conversion beyond 30% efficiency thresholds. Real-time AI algorithms dynamically adjust microbial growth conditions and nutrient inputs, stabilizing energy output against fluctuations in organic waste composition and environmental factors like pH and temperature. Scalability is validated through field trials, where bio-hybrid systems are co-deployed with small-cell base stations (SCBS), demonstrating resilience in both urban settings with intermittent waste availability and rural areas reliant on decentralized biomass sources. This model bridges synthetic biology and energy systems engineering, enabling self-sustaining network nodes while reducing reliance on carbon-intensive power grids39,40,41.

-

(i)

Microbial fuel cell (MFC) efficiency.

The efficiency of bio-hybrid energy is constrained by substrate conversion, electron transfer, and power circuit performance:

where:

-

\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{sub}}\) = substrate utilization efficiency (waste-to-energy conversion).

-

\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{electro}}\) = extracellular electron transfer (EET) efficiency.

-

\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{circuit}}\) = power circuit efficiency.

The substrate utilization efficiency is described as follows:

where:

-

\(\:{k}_{\text{cat}}\) = catalytic turnover rate of microbial enzymes.

-

\(\:{K}_{m}\) = substrate concentration at half-maximal efficiency.

-

[E] = concentration of electroactive bacteria.

-

\(\:\left[{S}_{\text{org}}\right]\) = concentration of organic waste in the MFC.

-

(ii)

Electron transfer efficiency

Electrogenic bacteria transfer electrons via redox reactions. The efficiency is modeled as:

where:

-

\(\:{\upgamma\:}\) = redox reaction rate constant.

-

\(\:{\Delta\:}pH\:=\:pH\) variation affecting electron transfer.

Energy storage and load balancing

The hybrid energy storage system combines bio-supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries to address the intermittent nature of bioenergy harvesting and fluctuating 6G network demands. AI-driven reinforcement learning algorithms dynamically allocate energy between storage units, prioritizing bio-supercapacitors for rapid charge-discharge cycles during peak loads while reserving lithium-ion cells for baseline stability, thereby minimizing combined weight and cost under lifecycle durability constraints. Load-balancing protocols adapt to real-time energy availability, factoring in microbial fuel cell output variability, thermal dissipation limits, and urban-rural grid reliability disparities to prevent outages and voltage drops. This approach harmonizes sustainability with operational resilience, critical for scalable 6G deployments. Hybrid energy storage includes bio-supercapacitors \(\:{C}_{\text{bio}}\) and lithium-ion batteries \(\:{C}_{\text{Li}}\), optimized as:

subject to:

where W is the weight factor and \(\:{C}_{\text{cost}}\) is the cost per unit capacity.

-

i)

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs): Reported power densities between 1 and 3 W/m² and conversion efficiencies up to 10–15%. These values were used to calibrate \(\:{\eta\:}_{bio}\) in our simulations.

-

ii)

Enzyme-catalyzed systems: Enzyme turnover rates (k_{cat}) in the range of 50–200 s⁻¹ and Michaelis constants \(\:{K}_{m}\) between 0.2 and 1.5 mol/L from experimental biochemical energy studies, supporting our choice of kinetic parameters.

-

iii)

Bio-supercapacitors: Recent prototypes demonstrate specific capacitances of 100–200 F/g and cycle lives exceeding 10,000 cycles, comparable to conventional electrochemical storage.

Socio-economic and deployment constraints

Deploying 6G ultra-dense networks faces region-specific challenges shaped by infrastructure readiness, economic viability, and public trust. Urban areas prioritize high-density small-cell base station (SCBS) deployments to meet bandwidth demands but grapple with space constraints for bioenergy bioreactors and elevated capital costs for hybrid energy storage systems. Rural regions, while benefiting from decentralized bio-hybrid energy solutions, encounter financial barriers due to limited grid connectivity and higher levelized energy costs (LCOE), necessitating subsidies or public-private partnerships to offset upfront investments. These constraints underscore the need for adaptive policies that balance technological innovation with equitable access and cultural acceptance. Urban and rural deployment constraints differ due to varying network densities:

In urban areas, supporting ultra-dense 6G connectivity requires deploying small-cell base stations (SCBS) at very high spatial densities. As shown in Eq. (32):

but space constraints limit the deployment of microbial bioreactors.

In rural areas, the required density of small-cell base stations (SCBS) is significantly lower compared to urban deployments as expressed in Eq. (33), showing that fewer than one hundred SCBS units per square kilometer are typically sufficient to provide coverage in less populated regions.

but face limited grid access, making bioenergy more viable.

-

(ii)

Cost optimization

The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is used to assess the long-term economic viability of bio-hybrid base stations, ensuring that energy generation costs remain competitive with conventional power sources. As shown in Eq. (34), LCOE accounts for both capital expenditure (CapEx) and operational expenditure (OpEx), discounted over the project lifetime at rate thereby reflecting the average cost per unit of energy produced.

-

\(\:\text{CapEx}\) = capital investment in microbial bio-energy systems.

-

\(\:\text{OpEx}\) = operational costs over the system’s lifetime.

Security and ethical considerations

The integration of bio-hybrid energy systems into 6G networks introduces unique security and ethical challenges that require careful qualitative assessment. Unlike traditional electronic-only systems, the inclusion of living biological components creates new dimensions of risk related to both cyber–physical vulnerabilities and public acceptance. Mitigating the risks of bio tampering in bio-hybrid 6G networks requires a combination of technical, biological, and system-level safeguards. Physical containment is the first line of defense, where bioreactors are housed in secure, closed modules that prevent unauthorized access and minimize the possibility of environmental leakage. At the biological level, genetic safeguards such as kill-switch mechanisms or nutrient dependencies can be engineered into microbial strains, ensuring that they cannot survive outside controlled environments. To detect malicious interference in real time, intrusion detection algorithms can be deployed to monitor microbial performance metrics, such as redox potential or growth rates, and flag abnormal deviations that may indicate tampering. Finally, system-level redundancy and isolation—through parallel operation of independent microbial consortia—ensures that even if one subsystem is compromised, overall functionality can be maintained without service disruption.

Addressing ethical concerns and building public trust require equally robust strategies. A foundation of transparency and communication is critical, supported by structured risk–benefit disclosure frameworks that make system performance, safety measures, and environmental impacts accessible to the public. Equally important is regulatory compliance, ensuring alignment with international biosafety standards (e.g., WHO, OECD) and verification through third-party audits. To strengthen societal acceptance, stakeholder engagement should occur early in deployment, involving local communities, regulators, and end-users in dialogue and decision-making. Moreover, ethical oversight boards dedicated to bio-hybrid telecom projects can provide continuous monitoring of societal impacts and evolving risks. In practical deployments, small-cell base stations should rely on modular bioreactor units that can be safely replaced or decommissioned if issues arise. To measure and communicate trustworthiness, a transparency index (τ) is retained as a conceptual tool, now explicitly linked to governance practices and community reporting mechanisms. Together, these measures create a layered approach to security and ethics, ensuring responsible deployment of bio-hybrid infrastructures.

Security risks

A major security concern involves the possibility of adversarial interference with microbial metabolic pathways, which could destabilize energy output or reduce system efficiency. While specific attack models remain theoretical, such risks highlight the importance of robust monitoring of microbial performance and the early detection of anomalous behavior. Rather than relying on speculative technical solutions, we emphasize practical safeguards such as redundancy in microbial consortia design, continuous system health diagnostics, and layered access control to limit unauthorized manipulation of bioreactor settings.

Ethical and biosafety risks

The deployment of genetically engineered microorganisms within public infrastructure raises issues of biosafety, regulation, and societal perception. Ethical considerations include potential environmental impacts, the safe handling of engineered strains, and the need for compliance with international GMO guidelines. Public skepticism toward “living networks” may present additional challenges. Addressing these concerns requires transparent governance, clear risk–benefit communication, and the establishment of oversight frameworks that prioritize safety and accountability.

Trust and transparency

Building public trust is essential for the acceptance of bio-hybrid telecommunications. One practical approach is to adopt transparency indices, where risks are systematically disclosed and weighed against benefits. Regular reporting of safety performance, third-party audits, and stakeholder engagement can help ensure that communities understand both the potential and the limitations of bio-hybrid systems.

The integration of bio-hybrid energy systems into 6G networks introduces novel vulnerabilities and societal challenges requiring proactive mitigation. Cyber-biological security addresses risks such as adversarial manipulation of microbial metabolic pathways, where malicious actors could reprogram genetic circuits to destabilize bioenergy output or induce system failures, necessitating AI-powered anomaly detection and blockchain-based audit trails to safeguard microbial consortia.

-

(i)

Cyber-biological threats

The integration of biological components into 6G base stations introduces new security vulnerabilities, as living systems can potentially be exploited in ways not relevant to traditional electronic infrastructures. Adversarial reprogramming could alter microbial metabolic pathways, reducing energy output or destabilizing system performance, thereby posing a critical risk to the reliability of bio-hybrid networks.

where \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{\text{adv}}\) represents malicious genetic modifications.

-

(ii)

Ethical constraints

Public distrust in bio-hybrid networks requires transparency indices:

indicate that at least 80% of risks must be disclosed to gain public trust.

Algorithmic implementation and multi-objective optimization framework for sustainable 6G ultra-dense networks

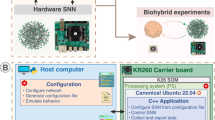

The implementation integrates advanced methodologies to address energy efficiency and system reliability. Genetic circuit optimization leverages CRISPR-based transcriptional tuning and metabolic flux analysis to rewire microbial pathways, targeting substrate utilization efficiency \(\:{\eta\:}_{\text{sub}}\) and electron transfer rates \(\:{\eta\:}_{\text{electro}}\) to achieve \(\:({\eta\:}_{\text{bio}}\ge\:30\backslash\:\%)\). Collaborative design between synthetic biologists and network engineers ensures microbial consortia are tailored for SCBS deployment, prioritizing robustness against pH fluctuations and organic waste variability. AI-driven power balancing employs reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms, such as Q-learning or deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG), to dynamically allocate energy between bio-supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries, minimizing \(\:W\cdot\:{C}_{\text{bio}}+{C}_{\text{Li}}\cdot\:{C}_{\text{cost}}\) while adhering to cycle-life constraints. Multi-agent RL frameworks enable decentralized decision-making across urban and rural SCBS clusters, adapting to real-time grid availability and bioenergy harvesting fluctuations. Monte Carlo simulations quantify outage probabilities under stochastic energy demand, microbial metabolic drift, and renewable energy intermittency. These simulations validate energy stability thresholds by correlating thermal dissipation limits, backhaul loss \(\in _{{backhaul}} ~\), and bio-hybrid storage resilience, enabling risk-aware deployment strategies for ultra-dense 6G networks.

Genetic circuit optimization

The design of genetic circuits focuses on reprogramming microbial consortia to maximize bioenergy efficiency through precision metabolic engineering. CRISPR-based tools and synthetic biology techniques are employed to edit metabolic pathways, enhancing substrate utilization and electron transfer rates in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) to achieve bioenergy conversion efficiencies exceeding 30%. Stability under real-world conditions is prioritized by engineering redundancy into microbial genomes, ensuring resilience against environmental stressors such as pH fluctuations and organic waste variability in both urban and rural deployments. Iterative lab-to-field validation cycles refine microbial performance, coupling computational models with bioreactor experiments to balance energy output with genetic load, ultimately enabling scalable, self-regulating bio-hybrid systems for sustainable 6G infrastructure. This approach bridges synthetic biology and network engineering, transforming organic waste into a reliable energy asset.

-

I.

Enzyme kinetics

The enzymatic processes governing substrate conversion in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) are modeled using Michaelis-Menten kinetics, a foundational framework for quantifying reaction rates under steady-state conditions. linking enzymatic performance to system-level energy output. This multi-scale approach bridges molecular biology and energy systems engineering, enabling predictive tuning of microbial consortia for sustainable 6G networks.

where \(\:\:v\:\): Reaction rate, \(\:{V}_{\text{max}}\:\): Maximum enzyme activity, \(\:\left[S\right]\): Substrate concentration, \(\:{K}_{m}\): Half-saturation constant.

To optimize substrate utilization efficiency \(\:{\eta\:}_{\text{sub}}\:\), a critical determinant of overall bioenergy efficiency \(\:{\eta\:}_{\text{bio}}\), the system enforces:

ensuring \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{sub}}\ge\:0.5\) when \(\:\left[S\right]\ge\:{K}_{m}\:\). (3) Environmental perturbations, such as pH shifts or temperature fluctuations, are incorporated via modified rate constants. For instance, temperature dependence follows the Arrhenius equation:

where \(\:A\) is the pre-exponential factor, \(\:{E}_{a}\) is the energy activation, \(\:R\) is the gas constant, and \(\:T\:\) is the temperature K. Competitive inhibition by metabolic byproducts is modeled as:

where \(\:\left[I\right]\) is the inhibitor concentration and \(\:{K}_{i}\:\)is the inhibition constant. These equations collectively inform CRISPR-based genetic edits to microbial pathways, targeting \(\:{K}_{m}\) minimization and \(\:{V}_{\text{max}}\) maximization for \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{bio}}\ge\:30\backslash\:\%\), while ensuring stability under dynamic bioreactor conditions.

-

II.

Metabolic control analysis

where \(\:{C}_{E}^{J}\): Control coefficient of enzyme \(\:E\) on pathway flux \(\:\:J\).

-

III.

Optimization problem

Maximize flux \(\:J\) through target pathways:

Where \(\in _{i}\): Enzyme efficiency, \(\:\left({\Delta\:}{G}_{i}\right)\): Gibbs free energy change.

AI-driven power balancing

The system employs reinforcement learning algorithms, such as Q-learning and deep deterministic policy gradients (DDPG), to dynamically optimize energy distribution between bio-supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries, prioritizing cost and weight efficiency while adhering to strict lifecycle durability requirements. These AI models continuously adapt to real-time variables, including fluctuating bioenergy output from microbial fuel cells, regional energy demand disparities, and thermal dissipation limits, ensuring stable power delivery across urban and rural network nodes. Use reinforcement learning (RL) to optimize energy storage and distribution. Q-Learning Update Rule could be represented as follows:

where \(\:\:{\upalpha\:}\): Learning rate, \(\:\:{\upgamma\:}\): Discount factor.

Monte Carlo simulations

The probabilistic framework employs Monte Carlo methods to evaluate the resilience of bio-hybrid 6G networks under stochastic energy and operational uncertainties. Thousands of randomized iterations model scenarios such as fluctuating bioenergy output from microbial fuel cells, abrupt traffic load spikes, and intermittent grid failures, quantifying outage probabilities and energy stability thresholds across urban and rural deployments. Simulations identify critical vulnerabilities. The results guide risk-aware infrastructure planning, balancing cost-performance trade-offs while ensuring compliance with ethical transparency indices and carbon neutrality targets, ultimately enabling robust, future-proof network architectures. Quantify outage probabilities and stochastic energy stability. The stochastic energy harvesting process of bio-hybrid systems is modeled as a combination of continuous and discrete random components, capturing variability in biological and environmental conditions as shown in Eq. (44):

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{\text{bio}}\): Mean bioenergy, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{\text{bio}}^{}\:\)Variability, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{\text{light}}\): Photon flux events.

The outage probability quantifies the likelihood that harvested bioenergy is insufficient to meet the total power demand of the base station over a given time horizon T as defined in Eq. (45):

The Value-at-Risk (VaR) metric is applied to quantify the worst-case shortfall in stored bioenergy at a given confidence level, providing a risk-oriented measure of system stability as expressed in Eq. (46):

Typically, \(\:{\upalpha\:}=\:0.95\)

Control and optimization framework

Expanding beyond reinforcement learning and Q-learning, this study highlights a broader suite of AI-driven control strategies that can enhance the adaptability of hybrid bio-electronic systems in dynamic environments. Model Predictive Control (MPC) provides an anticipatory mechanism by leveraging system dynamics to optimize inputs such as substrate feeding and storage switching over a finite horizon, making it particularly effective under fluctuating microbial performance and forecasted load conditions. Adaptive neural controllers, including deep recurrent architectures like LSTMs, capture temporal dependencies in bioenergy generation and predict short-term variations, enabling proactive energy balancing. In addition, hybrid rule-based and AI frameworks combine hard-coded safety constraints, such as minimum biofilm health thresholds, with data-driven optimization, ensuring interpretability without sacrificing adaptability.

In multi-node scenarios, multi-agent systems extend these concepts by enabling distributed base stations to coordinate energy use, share resources, and manage redundancy collectively. Practical adaptability is demonstrated through several examples: MPC can reallocate energy storage in response to toxin-induced reductions in microbial output; LSTM-based models can anticipate daily substrate consumption patterns, adjusting feeding schedules to stabilize energy supply; and multi-agent reinforcement learning allows one base station to offload tasks when another experiences a bioenergy shortfall. Together, these strategies move the control framework beyond theoretical constructs, demonstrating how real-time adaptability can strengthen both the reliability and sustainability of bio-hybrid 6G networks.

Results and analysis

This section presents the key findings derived from the simulations and analytical models developed in this study. Various performance metrics are examined to evaluate system behavior under different conditions, including energy efficiency, reaction kinetics, inhibition effects, risk quantification, and outage probability. The results are visualized through a series of plots that highlight critical relationships among variables such as energy input, substrate concentration, time duration, and system confidence levels. These visualizations provide insights into the operational limits, trade-offs, and sensitivity of the system components. By interpreting the patterns and trends observed, the section aims to validate theoretical assumptions and support the design of more resilient and efficient systems. The following figures serve as a foundation for drawing meaningful conclusions in the subsequent discussion. Together, they reflect the interdisciplinary integration of biological processes and network performance metrics, offering a holistic view of how synthetic biology can transform 6G infrastructure. The insights gained also inform practical guidelines for optimizing bio-hybrid network deployment in real-world scenarios.

Figure 1 illustrates how different components contribute to total network energy consumption as device density rises. At modest scales, transmission and computation are the primary drivers of energy demand, but in ultra-dense networks, cooling and backhaul requirements emerge as major contributors. For deployment, this trend implies that future 6G infrastructures must integrate advanced cooling technologies and energy-efficient backhaul solutions to avoid disproportionate overhead costs. Without such measures, the sustainability benefits of bio-hybrid energy harvesting could be undermined by escalating non-transmission energy demands. The blue region represents the energy used for transmission and computation, which forms a substantial portion of the total. The green segment depicts cooling energy, highlighting its significant role in overall consumption, while the thin red layer indicates backhaul energy, which remains relatively minor. This visualization underscores the importance of optimizing both transmission and cooling mechanisms to enhance energy efficiency in future 6G deployments. Moreover, it provides a clear framework for identifying target areas for sustainable energy innovations, particularly in the context of bio-hybrid and energy-autonomous base stations.

Figure 2 highlights the close relationship between computational workloads and cooling energy in small-cell base stations. As network load grows, computation requirements escalate due to tasks such as scheduling, optimization, and AI-driven management. This, in turn, increases thermal output, driving up cooling energy demand. For deployment, this indicates that improvements in computational efficiency must be paired with innovations in thermal management; otherwise, gains in processing efficiency will be offset by rising cooling costs. Incorporating energy-aware algorithms and high-efficiency cooling systems is therefore essential to maintaining the overall sustainability of bio-hybrid 6G networks. This trend implies that energy uncertainty due to weather variability becomes more significant over longer periods. Visualization provides critical insight into the influence of stochastic weather behavior on energy system reliability. By quantifying the probability of supply shortfalls, this figure supports the development of more robust system architectures capable of withstanding environmental uncertainty. Ultimately, such probabilistic modeling enables more informed planning for storage capacity, redundancy mechanisms, and real-time energy management in future sustainable networks.

Figure 3 displays a contour visualization of enzyme efficiency\(\:\:{\eta\:}_{\text{sub}}\) as a function of enzyme concentration E and substrate concentration \(\:{S}_{\text{org}}\). The color gradient represents varying efficiency values, with light shades corresponding to higher efficiencies. At lower substrate levels, increasing E leads to higher efficiency, evident in the concentrated lighter regions near the bottom of the plot. However, as \(\:{S}_{\text{org}}\:\)becomes large, the enzyme efficiency tends to plateau or decrease due to saturation effects. This figure demonstrates that backhaul energy grows substantially with rising data traffic, eventually becoming one of the dominant components of network energy consumption. In ultra-dense 6G scenarios, where high capacity backhaul, links are essential, inefficient backhaul infrastructure could impose a critical energy bottleneck. For deployment, this result emphasizes the need to optimize backhaul technologies through high-efficiency fiber systems, advanced compression techniques, or hybrid architectures so that the energy savings achieved through bio-hybrid power generation are not negated by unsustainable backhaul overhead. This ensures that both access and transport layers contribute to the overall sustainability of next-generation networks. This visualization aids in identifying optimal enzyme-substrate ratios for maximizing catalytic effectiveness in biochemical systems. Figure 4 underscores the importance of maintaining controlled operating environments: even with sufficient feedstock, elevated toxin levels can destabilize bio-hybrid energy systems. Robust monitoring and mitigation strategies are therefore required to ensure reliable power output in practical base station applications. However, as toxin concentration increases, the growth rate is significantly suppressed, regardless of how much substrate is available. This behavior reflects the dual influence of nutrient availability and toxin presence on microbial viability. The visualization highlights the sensitivity of microbial systems to environmental stressors, particularly toxins, even when nutrients are abundant.

Figure 5 shows the concentration of Species R, which exhibits an initial exponential increase followed by saturation, indicating that the system approaches a steady-state condition within approximately 20 h. This pattern is characteristic of microbial or biochemical systems where growth or accumulation occurs rapidly until limited by resource availability or equilibrium constraints. From a deployment standpoint, the result highlights that bio-hybrid energy systems require a stabilization period before reaching consistent performance. Designing base stations with adequate buffering or hybrid storage is therefore essential to ensure continuous operation during the early dynamic phase of microbial activity. This suggests a process governed by first-order kinetics, such as product accumulation in a biochemical reaction or the uptake of a resource by a saturating system. The gradual plateau implies that the system is reaching a steady state or equilibrium as time progresses. The smooth and continuous nature of the curve indicates stable dynamics without oscillations or sharp fluctuations.

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between channel capacity and the maximum allowable encryption key size under an overhead constraint of 0.1. The x-axis represents the channel capacity in megabits per second (Mbps), while the y-axis denotes the maximum key size in Mbps that meets the constraint. The shaded green region indicates the feasible range of key sizes that comply with the condition that encryption overhead remains less than or equal to 10% of the total capacity. The linear boundary reflects a proportional relationship where larger channel capacities allow correspondingly larger encryption keys. This ensures secure communication without violating bandwidth efficiency requirements. The plot serves as a design guide for selecting key sizes that maintain secure yet lightweight encryption within bandwidth-limited systems. From a deployment perspective, this figure provides a practical design guideline for configuring encryption parameters in bandwidth-limited bio-hybrid 6G networks, ensuring that data security is preserved while minimizing performance penalties.

Feasible region of encryption key sizes as a function of channel capacity under an overhead constraint of ≤ 0.1. The plot highlights the proportional scaling between secure key size and available bandwidth, providing a practical guideline for configuring encryption in bandwidth-limited 6G systems without exceeding efficiency thresholds.

Figure 7 presents a bar chart illustrating the breakdown of total energy consumption across different components in a network system. The three categories displayed are Devices Energy, Cooling Energy, and Backhaul Energy, measured in watt-hours (Wh). Devices Energy is the largest contributor, consuming 800 Wh, followed by Cooling Energy at approximately 630 Wh. Backhaul Energy contributes the least, with only 100 Wh, indicating its relatively minor role in total energy expenditure. The significant energy demands of devices and cooling systems highlight critical targets for optimization in energy-efficient network design. This breakdown provides valuable insights for engineers and researchers aiming to reduce operational costs and environmental impact. From a deployment perspective, the figure highlights that energy-efficiency strategies should prioritize device-level optimization and advanced cooling technologies, as improvements in these areas will yield the greatest reductions in operational cost and environmental footprint. Figure 8 presents a pie chart illustrating the distribution of total energy consumption, which amounts to 1100 Wh, across four primary components. Transmission Energy accounts for the largest share at 36.4%, indicating its dominant role in overall consumption. Computational Energy follows with 27.3%, underscoring the substantial energy demands of processing tasks in networked systems. Cooling Energy represents 22.7% of the total, reflecting the importance of thermal management in maintaining operational efficiency. Backhaul Energy contributes the smallest portion at 13.6%, showing it has a relatively minor impact on total energy usage. This visual breakdown is useful for identifying energy hotspots and prioritizing areas for efficiency improvements in network infrastructure.

Percentage contributions of transmission, computation, cooling, and backhaul to the total network energy consumption of 1100 Wh. The breakdown highlights the relative weight of each component, identifying transmission and computation as dominant drivers and guiding priorities for energy-optimization strategies in 6G system design.

Figure 9. illustrates the relationship between energy transmission and bio-efficiency over time. The blue line represents how transmission of energy steadily increases as time progresses, indicating a direct relationship between operational duration and energy consumption. In contrast, the red dashed line represents bio-efficiency, which remains constant regardless of time, reflecting its dependence on fixed internal system parameters. The graph emphasizes the difference in behavior between a dynamic energy metric and a static efficiency value. While energy requirements grow over time due to continuous activity, the bio-efficiency reflects an inherent characteristic of the system’s performance. This side-by-side comparison helps to distinguish between time-varying operational demands and the fixed efficiency of energy conversion mechanisms.

Comparison of transmission energy growth over time under constant bio-efficiency, illustrating the mismatch between increasing network energy demand and fixed system performance. The result underscores the need for adaptive bio-hybrid energy systems that can scale with dynamic load requirements in integrated 6G deployments.

Figure 10 demonstrates how substrate efficiency changes in response to increasing concentrations of organic substrate. As the concentration of substrate rises, the efficiency of substrate utilization decreases sharply at first and then more gradually. This trend suggests a diminishing return in efficiency as the system becomes saturated with substrate. The curve indicates that at lower concentrations, the system operates more efficiently due to higher catalytic responsiveness. As substrate levels increase, the active sites of the enzyme system may become saturated, reducing the system’s ability to maintain high efficiency. This visualization helps to understand the limitations of biochemical systems under varying substrate availability.

Inverse relationship between substrate efficiency and organic substrate concentration, showing how efficiency declines as biochemical systems approach saturation. This trend highlights the importance of controlled substrate dosing in bio-hybrid base stations to avoid wasted resources and maintain stable energy output.

Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between reaction rate and substrate concentration in a biochemical system. As the concentration of substrate increases, the reaction rate initially rises sharply, indicating high responsiveness at low substrate levels. Over time, the increase in rate begins to slow down, forming a curve that gradually approaches a maximum limit. This behavior reflects the saturation of enzymatic sites, where additional substrate no longer significantly boosts the reaction speed. The curve suggests that while substrate availability is crucial for activity, its influence diminishes once the system nears its capacity. This type of response is typical of enzyme-mediated reactions and helps characterize their kinetic behavior. Figure 12 demonstrates the effect of competitive inhibition on the reaction rate as substrate concentration increases. Multiple curves represent different levels of inhibitor presence, showing how the system responds under varying degrees of interference. As the inhibitor concentration rises, the reaction rate decreases at all substrate levels, indicating that the inhibitor competes with the substrate for the active site. Despite this inhibition, all curves eventually show a trend toward saturation, though the maximum rate becomes harder to reach with higher inhibitor levels. The separation between the curves highlights the sensitivity of the reaction to even small amounts of inhibitor. This visualization effectively captures the impact of competitive inhibition on enzymatic kinetics and provides insight into how biological systems regulate activity. Figure 13 illustrates the relationship between differential efficiency and energy input in a system where performance responsiveness diminishes with increased energy investment. As energy input begins at a low value, the system operates at its highest differential efficiency, indicating that small energy contributions yield relatively large performance gains. However, as energy input continues to rise, the efficiency curve steadily declines, suggesting a diminishing return on energy investment. This behavior reflects the inherent saturation effect observed in many biological and engineered systems, where additional energy no longer proportionally increases output. The curve visually emphasizes the need for careful energy budgeting, especially in self-sustaining or resource-limited scenarios such as bio-hybrid 6G networks. Understanding this efficiency trend is essential for optimizing energy allocation strategies and maintaining long-term system sustainability. Figure 14 illustrates how differential efficiency changes as energy input increases within a system. At low energy input levels, the differential efficiency is high, indicating a strong return on energy investment. As energy input rises, efficiency steadily declines, following a downward-sloping curve. This trend suggests diminishing returns, where each additional unit of energy yields a smaller increase in output. The curve highlights the nonlinear relationship between energy input and system response, emphasizing the importance of optimizing energy use. Such a pattern is commonly observed in biological and engineering systems where resource efficiency decreases with excess input.

Nonlinear increase in reaction rate with rising substrate concentration, illustrating saturation kinetics typical of enzymatic processes. The trend emphasizes that beyond a certain threshold, additional substrate provides little benefit, guiding optimal substrate dosing strategies for efficient bio-hybrid energy generation.

Effect of increasing inhibitor concentration on reaction rate across substrate levels, demonstrating the characteristic behavior of competitive inhibition in enzymatic systems. The result highlights the need for robust bioreactor designs that minimize exposure to inhibitory compounds, ensuring reliable and sustained energy output in bio-hybrid base stations.

Figure 15 displays the relationship between outage probability and the time duration over which energy availability is assessed. The curve remains flat and constant at the maximum value, indicating that the probability of outage is consistently high across all tested time windows. This suggests that the system is unable to meet its energy demands at any duration within the observed range. The flat trend line implies a persistent energy shortfall, regardless of how long the system operates. Such a result may highlight issues in energy harvesting, storage inefficiencies, or insufficient generation. This type of visualization is useful for diagnosing energy reliability in time-critical applications.

Constant outage probability across different time windows, reflecting a boundary-case scenario of persistent energy insufficiency. This result highlight’s critical reliability risks in bio-hybrid base stations and underscores the need for redundancy or hybrid storage solutions to ensure continuous operation in practical deployments.

The flat, maximum outage probability observed in this figure reflects a boundary-case simulation conducted under conservative assumptions of insufficient bioenergy harvesting capacity. This outcome does not indicate a modeling error but rather illustrates a critical deployment risk: if microbial fuel cells or hybrid storage systems are not adequately scaled, the base station will experience persistent outages regardless of the operational time window. This finding underscores the necessity of redundancy in system design, where multiple energy-harvesting units or hybrid storage buffers must be integrated to ensure resilience and continuous service in practical deployments. Figure 16 illustrates how the Value at Risk changes with varying confidence levels in an energy system context. As the confidence level increases, the Value at Risk decreases, indicating that higher certainty is associated with lower expected losses. This inverse relationship suggests that the system becomes less risky when aiming for greater reliability. The curve shows a gradual decline at first, followed by a sharper drop at higher confidence levels. This pattern reflects the conservative nature of risk assessment, where more stringent reliability demands require smaller acceptable risk thresholds. The graph provides useful insight into how risk management metrics behave under changing levels of confidence.

Inverse relationship between confidence level and Value-at-Risk (VaR), showing that greater certainty in energy availability corresponds to reduced expected risk exposure. This finding underscores the value of incorporating probabilistic risk analysis into bio-hybrid 6G network design to size storage systems appropriately and enhance reliability.

Discussion: insights into Bio-Hybrid 6G network performance and implications

A comprehensive understanding of the dynamic behavior of bio-hybrid base stations within ultra-dense 6G networks would be provided in this section. The energy consumption analysis demonstrates a clear linear correlation between the number of connected devices and the total power demand, with transmission and computation constituting the most energy-intensive components. Cooling requirements emerge as a substantial secondary burden, reinforcing the importance of thermal management strategies in future network design. Backhaul energy consumption, although relatively minor, should not be disregarded in long-term energy planning due to its cumulative effect across large-scale deployments. The probabilistic analysis of energy supply under varying weather conditions highlights the vulnerability of traditional renewable systems to environmental volatility, with outage probability increasing under higher uncertainty and longer durations. These findings validate the necessity of incorporating stable and continuous bioenergy sources, such as microbial fuel cells, to supplement or replace intermittent energy systems. Furthermore, enzyme and microbial kinetics visualizations confirm the saturation behavior typical of biological processes, underscoring the critical need for careful calibration of substrate concentrations and toxin tolerance thresholds to maintain system efficiency.

The contour plots of enzyme and microbial activity offer key insights into how synthetic biological systems can be tuned for maximum performance in fluctuating environments. Enzyme efficiency is shown to be highest at moderate substrate concentration. Microbial growth is likewise inhibited at high toxin concentrations, even in the presence of ample substrate, indicating the necessity of maintaining balanced biochemical conditions within microbial fuel cells. The reaction rate curves further affirm the non-linear nature of enzymatic responses, with competitive inhibition causing a noticeable decline in reaction efficiency across all substrate levels. These biological constraints underscore the importance of genetic circuit optimization to enhance system resilience under practical deployment scenarios. Differential efficiency analysis reinforces the concept of diminishing returns in energy systems, emphasizing the need for adaptive energy management protocols to optimize performance across varying load conditions. These biological and computational findings collectively highlight the intricate interplay between system design, environmental inputs, and bio-hybrid behavior.

The risk-based performance metrics, including outage probability and Value at Risk (VaR), provide additional depth in evaluating the operational reliability of bio-hybrid networks. Monte Carlo simulations reveal that under current configurations, persistent energy insufficiency can occur if bioenergy systems are not adequately scaled or managed, especially in high-demand urban settings. The flat outage probability curves observed indicate that without proper load balancing and predictive storage control, energy autonomy may not be consistently achievable. Conversely, the VaR analysis shows that with increased confidence levels, expected energy shortfalls significantly decrease, suggesting that strategic energy buffering and risk mitigation can yield more robust system performance. Integrating AI-powered storage optimization, as demonstrated in the study, becomes essential in mitigating the volatility of bioenergy harvesting and maintaining service continuity. These findings align with the broader goal of creating sustainable and self-regulating network architectures, where biological efficiency and algorithmic intelligence coexist. In summary, the results not only validate the feasibility of synthetic biology-enabled 6G base stations but also point toward the future need for interdisciplinary coordination across biology, engineering, and data science to fully realize their potential.

The integration of synthetic biology into telecommunications infrastructure also raises crucial considerations regarding scalability, ethical deployment, and public acceptance. Urban and rural deployment models exhibit contrasting challenges urban environments benefit from high network density but suffer from space constraints for bioreactor installation, while rural areas have more physical space but limited grid access, making decentralized bioenergy systems more attractive yet financially challenging. These socio-technical trade-offs must be addressed through adaptive infrastructure policies and economic incentives such as public-private partnerships or targeted subsidies. Furthermore, ethical concerns surrounding the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in public systems necessitate transparent risk communication and compliance with international biosafety standards. The introduction of transparency indices and deployment scores, as proposed in this study, offers a systematic way to evaluate and enhance public trust. Additionally, security vulnerabilities related to cyber-biological interference, such as adversarial manipulation of microbial metabolic pathways, must be proactively mitigated through secure genetic circuit design and blockchain-based monitoring systems. Public perception plays a pivotal role in the large-scale rollout of bio-hybrid systems, and user-centered design frameworks must incorporate feedback from diverse stakeholder groups. These broader implementation aspects demonstrate that while the technological feasibility of bio-hybrid 6G networks is promising, their successful adoption will depend equally on social, regulatory, and ethical readiness. Thus, future research must extend beyond technical optimization to embrace inclusive, secure, and transparent deployment strategies.

Mitigating electron transfer losses under fluctuating pH and temperature conditions requires a combination of biochemical stabilization and adaptive monitoring. One effective approach is the incorporation of pH-buffering electrolytes, such as phosphate- or bicarbonate-based buffers, to maintain stable local microenvironments. Complementary to this, the use of thermostable redox enzymes and genetically engineered microbial strains with broader tolerance ranges can enhance resilience against environmental variability. In parallel, real-time biosensors that continuously monitor redox potential and detect environmental drift can trigger adaptive adjustments in feedstock delivery or circuit load, ensuring that electron transfer efficiency is preserved under dynamic conditions. Together, these strategies provide both proactive and reactive mechanisms for safeguarding bioenergy conversion in bio-hybrid systems.

Equally important is ensuring the long-term stability and functionality of microbial consortia. Designing synthetic consortia with complementary metabolic pathways allows for redundancy, so that if one microbial population declines, others can maintain energy generation. Biofilm engineering techniques, including extracellular polymeric substance enrichment and quorum sensing modulation, can further strengthen structural robustness and prolong system viability. Operational strategies such as periodic substrate cycling and controlled toxin flushing help reduce metabolic stress, while coupling bio-hybrid units with bio-supercapacitors provides buffering capacity, reducing peak-load stress on the microbial systems. For deployment in small-cell base stations, modular bioreactor designs are recommended, enabling units to be replaced or regenerated without full system downtime. These measures not only extend microbial longevity but also align with biosafety regulations, ensuring that bio-hybrid energy systems operate within controlled and monitorable environments suitable for real-world 6G applications.

Future work

This study has demonstrated the feasibility of bio-hybrid 6G base stations through mathematical modeling and simulation, providing evidence that synthetic biology can play a transformative role in enabling energy-autonomous telecommunications. However, further steps are required to translate this conceptual framework into deployable infrastructure. First, long-term bioreactor field trials are essential to validate the stability, efficiency, and scalability of microbial fuel cells and enzyme-driven systems under real-world conditions. Such trials should measure not only energy autonomy but also durability under fluctuating temperature, pH, and toxin exposure, providing operational datasets that can guide engineering refinements. Second, the integration of AI-driven control systems should be explored to optimize adaptive energy management. Beyond reinforcement learning, advanced approaches such as model predictive control, recurrent neural networks, and multi-agent coordination can help base stations adjust dynamically to variations in bioenergy output and network load, ensuring reliable and resilient service.

Third, socio-technical frameworks must be refined to address issues of public trust, regulatory compliance, and ethical governance. This includes transparent communication of risks and benefits, alignment with international biosafety standards, and mechanisms for stakeholder engagement to build legitimacy for deploying “living networks” in public spaces. Finally, expanded risk assessment models should be developed to couple biosafety with network-level reliability. These models must capture interactions between microbial system vulnerabilities and telecommunications performance metrics, enabling comprehensive resilience planning.

Conclusion

This study presented a comprehensive mathematical modeling framework for bio-hybrid 6G base stations powered by microbial fuel cells and enzyme-driven energy systems. By integrating stochastic energy harvesting dynamics, outage probability analysis, and risk-oriented measures such as Value-at-Risk, the model demonstrates the theoretical feasibility of achieving energy autonomy while reducing carbon emissions in ultra-dense 6G networks. The results highlight both the resilience and sustainability potential of bio-hybrid systems, particularly when supported by efficient storage and adaptive control strategies. At the same time, we recognize that these findings are primarily simulation-based. While the models validate feasibility and resilience in principle, large-scale scalability must be confirmed through controlled field trials and experimental validation. Such efforts are essential to test long-term stability, optimize microbial performance under real-world conditions, and refine socio-technical frameworks that ensure public trust and regulatory compliance. Simulation results validate the effectiveness of AI-driven power balancing strategies and identify key thresholds for outage probability and value at risk, offering practical tools for real-time energy management. Moreover, the discussion addresses the socio-economic and regulatory implications of deploying living technologies in both urban and rural contexts, emphasizing the need for transparency, public engagement, and robust cyber-biological security. Ultimately, this research positions synthetic biology as a critical enabler of self-sustaining, carbon-neutral 6G communication systems. Future work should expand on field validation, long-term bio-reactor performance, and human-centered design to ensure that bio-hybrid networks are not only technologically viable but also ethically sound and socially accepted.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhan, S. & Chong, A. Building occupancy and energy consumption: case studies across building types. Energy Built Environ. 2, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbenv.2020.08.001 (2021).

Khanh, Q. V., Hoai, N. V., Manh, L. D., Le, A. N. & Jeon, G. Wireless communication technologies for IoT in 5G: vision, applications, and challenges. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 3229294. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3229294 (2022).

Hemanand, D. et al. Enabling sustainable energy for smart environment using 5G wireless communication and Internet of Things. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 28, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.013.2100158 (2021).