Abstract

Field based ecological studies are efficient tools enabling decision makers to keep an eye on the health of forest ecosystem especially under anthropogenic stress. In current work, by employing the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) technique, we have evaluated the ecological health status of 3 riverine forests comprising of 110 plants species. The results revealed a negative connection of anthropogenic activities with the FQI. FQI scores and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) exhibited a good correlation and co-variance at the places with high degree of human interference. The mean FQI score of these forests was 25.31. The Coefficient of Conservatism (CC value) score ranked 40 species at grade 0, 33 species into the range 1–3, 25 species into the range 4–6, 9 species in the range 7–8 and only 3 plant species attained the top score in the range 9–10. Bela Qila Jawar Singh (QJS) forest had the highest number of exotic species i.e., 36% followed by Khangarh (KG) forest (33%) and Thatha Faqir Ullah (TFU) forest (32%). Cluster Analysis (CA) revealed that QJS and TFU forests showed closer similarity in species composition, while Khangarh forest was ecologically distinct. Indicator species analysis revealed that intermediate groupings (Rankings 1–3 and 4–6) contained the majority of significant indicator species, with several species exhibiting high fidelity and specificity, indicating distinct compositional differentiation. The p-value (≤ 0.05) confirms their strong statistical reliability as indicator species evident of the disturbed health status of this environment. This study can assist in developing efficient management techniques, which makes it quite intriguing to protect ecosystems especially riverine forests from anthropogenic and climatic threats to biodiversity. Strengthening habitat restoration and reducing human-induced disturbances are recommended to improve forest health. The recovery of indicator and native species should be the main focus of efforts. To monitor development and preserve ecosystem stability, it is also recommended to conduct ecological evaluations on a regular basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Riverine forests are distinct, internationally significant ecosystems that support a wide range of vulnerable plant species1. Agricultural growth, unchecked grazing, fuel wood collection, overexploitation, and border conflicts pose serious threats to these woods, notwithstanding their critical importance1. Pakistan is a climate susceptible country due to abrupt extreme weather events like a series of intense rainfalls that resulted in flash, urban, and riverine flooding in 20222 and most recently in 2025. The population living along riversides has been largely uprooted by riverbank erosion3, which has resulted in human casualties, loss of assets and revenues from livelihoods, and a loss of historical identity4. Rising riverbank erosion is mostly caused by factors such as increasing riverine encroachments, poor water resource management, improper farmed land use, crucial geological location, and climate dynamics5.

Pakistan has a significant deficiency in forest areas; only 5% of its territory is covered by woods. Between 2017 and 2021, a few areas in Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were subjected to the Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) program, which was a joint venture between the Ministry of Climate Change (MoCC), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Its main objective was to promote sustainable management practices in Pakistan’s riverine forests, subtropical broad-leaved evergreen thorn forests and Western Himalayan Temperate Coniferous forests. The goals of this endeavour were to mitigate climate change, improve biodiversity protection and maintain the services provided by forest ecosystems6.

To really focus on managing, protecting, and restoring our forests, we need a smart way to find high-quality forests, keep an eye on restoration projects and check how well our management activities are working. It isn’t practical to track every little human impact on riverine forests because there are just too many and they’re quite complicated7. Human disruptions, both in time and space play a huge part in which plant species can hang on or thrive in any given area. So, when we look at what type of plants are growing in a specific place, we’re really seeing how past and present impacts come together. This can tell us about the ecological health or condition of that spot.

We know quite a bit about how different plants respond to various conditions or stressors. This knowledge helps to pinpoint specific changes that might affect the forest’s health and overall balance1. People are not only to blame for the disruptions that allow exotic plants to invade, but they also serve as trajectories for the spread of exotic plant species across the woodland environment through the propagule transport process8. It has been noted that the parameters that generate disturbances can filter the makeup of a community and affect species occurrence by altering the availability of resources and habitat9. The effects of regional and taxonomic parameters on the rapid growth of invasive species are not well understood10. Therefore, it’s important to investigate the effects of spatial heterogeneity and identify the circumstances that a species is most vulnerable11. Due to their competition for resources, exotic plant species have an impact on nearby native plant species12. They take up space and deplete soil nutrients, which hinders the growth of nearby vegetation.

Globalization of the market, quick travel, the tourism sector and increased trade between countries are all significant factors that have contributed to the noticeably increasing number of biotic invasions over time13. In order to address pressing global environmental issues like climate change, habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution and contamination, disease outbreaks and the spread of invasive species, many ecologists and environmental scientists are trying to find management solutions14. Conservative plants find it difficult to adapt to these changes brought about by humans. As a result, they frequently disappear from places affected by human activity first15.

The FQI was first made for the Chicago area and this gives an idea that how to assess the degree of “naturalness “of an area16. The FQI offers a distinct method of ecological monitoring and assessment tool that goes beyond basic measurements of species richness and abundance and instead provides an approximation of the quality of native plants at a site17. FQI has been tried out and proven useful in 11 different States and Provinces. America has led the development and adoption of FQI evaluation methodologies18, Virginia19, Montana20, Ohio21, Indiana22, Florida23, North Dakota24 and Wisconsin25 are among the states where the FQI has been developed and tested. Numerous organizations, including the Missouri Department of Conservation26, county governments27 and The Nature Conservancy28 use FQI indices to identify and prioritize high quality natural areas to include in their Natural Areas network.

The foundation of the FQI is a coefficient of conservatism (CC) score, which is applied to every species of plant in the local flora and is scored from 0 to 10. A species’ specialization to a particular type of habitat and its tolerance to disturbance are reflected in its score. A panel of knowledgeable local plant experts decides on and assigns CC scores. A ‘C’ value of 10 goes to those plants that really need high-quality environments and cannot handle any habitat loss, they’re highly loyal to their natural communities. On the other side, a C value of 0 is for plants that can handle human disturbances and don’t stick closely to any real natural community. The distinction between a value of 0 and a value of 3, on the other hand, is more pronounced conceptually than the difference between a value of 0 and 1, or between 9 and 10. Coefficients of conservatism (CC) are not applied to introduced (exotic) plants because, by definition, they were not a part of the original landscape before European settlers arrived [some even suggest that they should be assigned a C value of 0]22.

Ecological indicators are essential tools for evaluating an ecosystem’s stability, health, and functionality. They are species or groups of species whose presence, abundance, or physiological state corresponds to particular environmental states, such as disturbance, pollution, or habitat integrity29. With plant-based indicators being acknowledged as efficient monitors of habitat disturbance, ecological homogenization, and biodiversity change, the use of Indicator Species Analysis (ISA) has recently extended into vegetation and forest-ecosystem studies30,31. The application of indicator species has been expanded in modern forest-ecosystem studies to track biodiversity status, restoration results and the integrity of ecosystems32. As ecological barometers, these species assist researchers in assessing habitat quality, human pressures, and the effectiveness of management initiatives. Therefore, the use of environmental metrics is essential for long-term monitoring, conservation planning, and effective management of forests31.

When considering the ecological health of riverine habitats, plant communities in riverine corridors can act as trustworthy indicators since they respond to human pressures differently than individual plant species18. The geographical habitat characteristics of the riverine zones of the River Meuse in Belgium were examined33. In the riverine ecosystems of Southeast Minnesota, the effects of non-grazing on plant patterns and bank stability were investigated34. Similar to other developing nations, Pakistan has experienced extreme ecological degradation of its forest ecosystem as a result of human activities like clearing land, excavating ditches and canals, siltation, channelizing rivers and streams, grazing and browsing, sandstone quarries, water mining for agricultural and urban use35.

The Gujranwala Forest Division experiences hot, dry summers and mildly chilly winters. April marks the beginning of the summer season, which lasts till September with typical highest and lowest temperatures of 40 and 27 degrees Celsius. June is the warmest month. The winter period starts in November and continues till March. The month with the extreme cold is January. This month’s average high and low temperatures are 19 °C and 5 °C, respectively. Monsoon season starts in the month of July, which lasts until September. Rainfall is higher in the eastern portion of the division. The forest division receives 2660.07 millimetres of rain on average per year. The rate of wind has been recorded to be between 5 and 12 km/h on the majority of days, while the wind direction is primarily west-northwest toward the north and ends up at east-southeast.

Unfortunately, riverine forests around Gujranwala Division aren’t just disappearing but they are also contributing to climate change by a number of human activities, including industry, grazing, resource extraction, lumber harvesting and more specifically urbanization36. Due to the area’s exotic species invasion, dispersed population and demand-driven overharvesting can result in population reduction and biodiversity loss10. Fertile agricultural and forest lands are being overused by land grabbers for their purported “Housing Schemes” at faster rate. So, it is essential to examine and assess the phyto diversity and floristic quality of riverine forest. To tackle this challenge of monitoring and restoring our green spaces, we should come up with some simple but effective analytical tools. FQI has been embraced by environmental scientists, decision-makers, land stewards and restoration ecologists19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

The main goal of this project is to assess the environmental integrity and health of the riverine forests along the River Chenab and its tributaries. The majority of ecological research in this field consists of floristic inventories; very little is known about the vegetation composition and plant diversity of Gujranwala riverine forest flora. To the best of my knowledge, these forests have not been the subject of any previous FQI research. In order to close this study gap, the FQI was used as an ecological indicator to statistically analyse 3 riverine forest resources across the study area in order to preserve field data and lessen the data scarcity. We will proceed with the hypothesis that “riverine woodland areas are not vulnerable to the influx of exotic species and disturbances”. The scores from the FQI can be used to prioritize forests (or other ecosystems) for management, restoration, or protection, as well as to monitor the success of these efforts. This study also highlights the current state of botanical resources and the role of anthropogenic and ecological factors in the distribution patterns of the local vegetation, which will be useful for strategic planning by ecologists, researchers, agriculturists, policy makers and conservation biologists. This is a first attempt to implement Floristic Quality Index (FQI) on Gujranwala riverine Forest Division emphasizing the need for improved future conservation of riverine forests impacted by anthropogenic activities.

Materials and methods

Study area

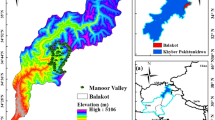

Study area is comprised of 2790-acre strip of alluvial rich land that includes three riverine forests: Bela Thatha Faqir Ullah (TFU), Bela Qila Jawar Singh (QJS), and Khangarh (KG) located between the two well-known rivers, the Chenab and the Ravi, in the centre of “Rachna Doab” is the Forest Circle of Gujranwala (Fig. 1). Nearly every Tehsil in this area has a network of riverine woods that cover 44581.61 acres. It serves as the ‘hub’ of biodiversity. The study area map was generated using QGIS (version: 3.38 Grenoble, Release date: 2024-06-21).

Identification

The administrative jurisdiction, geographic location and types of forest vegetation were confirmed through an analysis of the Gujranwala Forest Division. Floristic surveys were carried out between 2022 and 2024 during winter and summer seasons in order to compile a list of botanical diversity. The riverine forest sites found in the Gujranwala Forest Division are TFU, KG and QJS. Using a GPS device, the locations located in the Riverine Forest were measured for altitude and geo-coordinates. Using the floristic literature that was available, the collected plant specimens were identified37,38,39. Additionally, specialist websites (https://www.efloras.org) were utilized to categorize plant species as native or exotic based on readily available data sources. For reference, the voucher specimens were submitted to the Dr. Sultan Ahmed Herbarium, Department of Botany, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan.

Data collection

A stratified random sampling design was used to study the qualitative and quantitative attributes of plant community. This design made it possible, producing a balanced and statistically reliable dataset to thoroughly assess the species’ structure and composition for quantitative analyses, including FQI, Indicator Species Analysis (ISA), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)40. Two sites within the same forest were chosen on the basis of variations in the level of disturbance, types of vegetation, microhabitat conditions, accessibility and vegetation density. Dense, comparatively undisturbed vegetation was found at one site, but substantial anthropogenic disturbance was seen at another site. In order to ensure a meaningful comparison of floristic composition and community structure, both sites were of similar size and ecological environment. Sampling of the vegetation was performed through quadrat method41. Size of quadrat was determined through species-area curve. Coordinate measurements were taken for every sample quadrat in order to create a GIS (Global Information System) map that could be used as a guide, and within each site of Riverine Forest, thirty (10 m × 10 m) quadrats including trees, shrubs and herbs were arranged at random to promote floristic diversity42,43. The current study sampled 180 (30 × 6 = 180) quadrats. Biological spectra (Habit and Life Form) as qualitative attributes were determined44. The quantitative assessment was carried out by calculating percentage frequency, density and percentage cover44,45,46 respectively. Based on these three basic parameters, Importance Value Index (IVI) was calculated47.

Coefficient of conservatism values (CC)

In order to assign CC value to each species in the community based on how sensitive it was to human disturbance under various environmental conditions, we invited five (5) field botanists with regional experience, having taxonomic and herbarium expertise and ecological field experience. The final score was based on averaging, consensus or discussion by using the methodology43,48,49,50. The score on the list was assigned a number between 0 and 10 and the index was produced as follows:

where ∑Cn is the sum of each native species’ coefficients of conservatism values. N is the number of native species, while C̄ is the mean value of conservation coefficient. The total forest vegetation was then separated into five ranges, which are ranked as follows: grade 0, grade 1–3, grade 4–6, grade 7–8, and grade 9–10 (Table 1).

Floristic Quality Index (FQI)

Based on the presence of ecologically significant species, the FQI was used to gauge the extent of human disturbance in an area by accounting for the presence of native and exotic species to evaluate how natural an area is51. The FQI was calculated using a list of plant species for the entire forest area.

Ordination analysis

The data sets pertaining to vegetation and habitat type were subjected to the ordination approach utilizing two forms of multivariate analysis. Sites were grouped using cluster analysis (CA) based on comparable floristic composition. To group sites based on floristic composition, Ward’s approach was employed as a linkage method and Euclidean (Pythagorean) as a distance measure. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to analyse the multi-dimensional data in order to find potential variables, or components, that could account for as much variance as feasible data52 by using Origin Pro 2024b (Learning Edition). Chord diagrams were created using the Origin Pro 2024b (Learning Edition) application. We were able to determine from this graph which species were associated with which types of habitats, the ranking category each species fell into and the quantity of every species in each group53. Multivariate analysis was examined using Past 4.13 to understand the indicator species analysis (IndVal) for each group type54. Heat Maps were designed to visualize the intensity and value of Native and Exotic indicator species across two axes55.

Results

Floristic diversity and distribution

110 plant species from 36 families and 94 genera were identified from the research region (Table 2). There was an uneven distribution of families: five families accounted for half of the species, while the remaining groups were represented by thirty-one families, many of which (18) were monotypic families (Table 2). In the research region, most species-rich families were the Asteraceae with 16 species, Fabaceae with 12 species, Poaceae with 10 species, Malvaceae with 8 species and Solanaceae with 7 species (Table 2). On the basis of plant habit, the flora of the region could be divided into herbs (59%), trees (24%), shrubs (7%), climbers (1%) and Ferns (1%) (Fig. 2A). In the floristic research, therophytes (36.36%) ranked first followed by phanerophytes (31.81%), chamaephytes (15.45%), hemicryptophytes (11.81%), geophytes (3.63%) and helophytes (1%) (Fig. 2C) (Table 2).

Nativity of riverine forests

In the current study, Solanum was found as the dominant genus with 04 species reflecting their wide ecological amplitude and ability to tolerate disturbed environmental conditions. 14 genera such as Acacia, Abutilon, Chenopodium, Eucalyptus, Ficus, Lantana, Morus, Oxalis, Polygonum., Ranunculus, Salix, Sida, Verbena and Zizyphus were represented by 02 species each, indicating moderate diversity. In contrast, 78 monotypic genera were also recorded, each represented by a single species within the study area reflects ecological stress and habitat disturbance, where only a few resilient genera persist while most exhibit limited distribution. There were 40 (36%) exotic species and 70 (64%) native species in the research area’s flora (Fig. 2B). Asteraceae (09 species), Fabaceae (05 species), Malvaceae (03 species) and Solanaceae (04 species) were the most prevalent exotic species families. The TFU forest site had the maximum percentage of native species (68%) surveyed by KG forest site (67%) and QJS forest site (64%) while the ratio of exotic species is 32% in TFU forest site, 33% in KG forest site and 36% in QJS forest site (Table 2).

Distribution by habitat

In the study area, KG forest habitat accounted for more than 42% of the total species pool, followed by QJS forest at 30% and TFU forest at 28%. The number of species found in each site of Riverine Forest is indicated by the thickness of each bar in the chord diagram, whereas the lines orientation indicated which species belong to which site of forests. The complete names of the plant species were shown in Table 2 (Fig. 3).

Floristic Quality Index (FQI)

On the FQI scale, the Riverine Forest had a mean FQI of 25.31. The FQI found that 40 of the exotic plant species growing in the Riverine Forest were ranked 0, with 33 species ranking 1–3 followed by 25 ranking 4–6, 09 ranking 7–8 and 03 ranking 9–10 (Fig. 4). Species that are vulnerable included L. dissecta, D. juxtaposita, S. erianthum, R. sceleratus, D. chinensis, among others. The CC-value of each plant species in the forest area are accessible in the Table 2. In the current study, the KG forest site 2 had the uppermost FQI value (27.83), while the QJS forest site 2 had (26.11) and lowest (23.35) for TFU forest site 2 (Table 3).

Distribution of species in Gujranwala Forest Division, Pakistan, based on categories of Riverine Forests. The number of species found in each kind of Riverine Forest is indicated by the thickness of each bar, whereas the lines orientation indicated which species belong to which types of forests. The complete names of the plant species are shown in Table 2.

The floristic quality index (FQI) score in the Riverine forests of the Gujranwala Forest Division, Pakistan, shows the distribution of species. Each bar’s thickness indicates the number of species within that ranking category, while the lines’ orientation indicates which species are associated with certain types of ranking. The species’ complete names are shown in Table 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

In the study area, FQI based PCA was done by adding the input matrix as the CC-value data of trees and shrubs species. The site-focused scaling (scaling 1) was used to highlight the variations and similarities among sampling sites according to their plant species composition. The vectors are represented by sites in this scale, which indicate the degree and direction of variation among them, while species are represented by dots, which indicate their association with certain sites. The species loadings (scores), were derived using the correlation matrix of the normalized CC-values data, which show how each species contributes to the ordination axes and aids in the explanation of site differentiation patterns (Supplementary Table S1 online). PCA was applied to the sets of six riverine forest sites in order to gather comprehensive data on the trend of variation. This allowed us to get six PCs. Table 4 displays the eigenvalue and explained variance ratios, showing a progressive decrease in PC variance.

A scree plot (Fig. 5) illustrates the explained contribution made by variances to the overall variance. The first and second axes of the PCs explained 50.03% and 29.95% of the total variance. The different community composition of the QJS and TFU sites is easily distinguished from that of the KG sites by the PCA ordination. KG locations appear to be structured by a distinct set of ecological characteristics than the other sites, as evidenced by their grouping along the negative side of PC1 and higher PC2 values. S. cumini ‘s relationship with KG forests, which reflects its dominance and ecological preference there, is a major factor in this split. On the other hand, species like B. ceiba, B. papyrifera, P. serrattifolia, and S. alba significantly contribute to the ordination of QJS and TFU sites, which are grouped on the positive side of PC1. This pattern, which is influenced by species that are either absent or less prominent in KG, shows that QJS and TFU have a higher floristic similarity. Overall, the PCA shows how species-specific relationships influence compositional divergence, with QJS and TFU displaying overlapping ecological communities and KG reflecting a distinct floristic assemblage (Table 5, Fig. 6).

Riverine Forest sites (KG, QJS, and TFU) were arranged using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) according to species composition. While QJS and TFU sites cluster on the positive PC1 axis, driven by species including Bom. cei, Bro. pap, Pre. ser and Sal. alb, KG sites plot at negative PC1 and higher PC2 values, predominantly related with Syz. cum. In contrast to the ecological similarities of QJS and TFU, the ordination emphasizes the unique floristic assemblage of KG sites. Details of species codes refer to Table 2.

Two way hierarchical cluster analysis

The presented dendrogram (Fig. 7) illustrates the hierarchical clustering of riverine forest sites based on their similarity in vegetation composition on the basis of IVI data (Supplementary Table S2 online). The horizontal axis displays the several forest locations (KG1, KG2, QJS1, QJS2, TFU1, and TFU2), while the vertical axis displays the similarity index (in percentage). Visual separation of clusters highlights various branch colours (red, orange, yellow, green, cyan and blue) which helps to assess the degree of similarity across the forest areas. Within the sites, the pattern of clustering indicates a good similarity level between KG1 and KG2(58%), a high similarity between QJS1 and QJS2 (67%) and a strong similarity between TFU1 and TFU2 (85%). This exhibits their resemblance in species composition and ecological characteristics. The KG sites integrate at the lowest similarity, suggesting that their species composition is relatively unique and more distinct from that of the QJS and TFU sites in species composition and ecological dynamics. The QJS and TFU sites share a 16% similarity in cluster patterns, this shows that these forests sites exhibit some common ecological attributes or drivers and anthropogenic stresses.

Shows a dendrogram based on species similarity hierarchical cluster analysis among riverine forest sites (KG1, KG2, QJS1, QJS2, TFU1 and TFU2). KG1 and KG2 form a distinct cluster, QJS1 and QJS2 form a compact group, and TFU1 and TFU2 cluster together. The QJS and TFU clusters merge at a moderate similarity, whereas the KG sites combine at the lowest similarity, indicating that their species composition is different from the other sites.

Indicator species analysis

In this study out of 110 total species, 71 indicator species were identified, that were strongly associated with their habitats (Supplementary Table S3 online). Indicator species study showed that a number of taxa functioned as major ecological indicators with p-values ≤ 0.05 demonstrating their substantial correlation with particular ranking groups (Fig. 8) The intermediate groupings (Rankings 1–3 and 4–6) contained the majority of significant indicator species, with several species exhibiting high fidelity and specificity, indicating distinct compositional differentiation. A. modesta, A. nilotica, A. aspera, A. lebbeck, B. diffusa, C. procera, C. ciliaris, C. dactylon, D. sissoo, D. bipinnata, D. annulatum, D. radicosa, F. carica, F. virens, L. camara, L. nudicaulis, M. coromandelianum, M. azedarach, M. alba, M. nigra, O. corniculate, P. annua, P. plebeium, P. supina, R. dentatus, S. munja, S. dulcis, S. irio, T. aphylla, T. angustifolia, Z. mauritiana and Z. nummularia were highly specific and strong ecological indicators in Ranking 1–3 whereas, A. punjabensis, B. lacera, B. ceiba, B. papyrifera, C. sativa, C. iberica, C. pulchellum, C. asiatica, C. album, C. arvense, E. alba, E. indica, E. ramosissimum, M. pumilus, M. denticulate, P. persicaria, P. monspeliensis, P. serratifolia, S. cordifolia, S. rhombifolia, S. nigrum, V. Thapsus, V. officinalis, W. heynei, W. somnifera and W. fruticose are reliable indicators of the 4–6 community cluster. In contrast, Rankings 7–8 yielded fewer significant indicators as D. chinensis, E. suberosa, M. parviflora, P. juliflora, P. dysenterica, R. muricatus, R. sceleratus, S. alba, S. cumini and V. anagallis-aquatica. Rankings 9–10 yielded fewer significant indicators as D. juxtaposita, S. erianthum, L. dissecta. Strong indicator species were absent from Rankings 0, indicating that generalist taxa or less organized communities predominated. Overall, the distribution of low p-values across groups emphasizes how indicator species linked to intermediate ranks best describe community identity, highlighting their ecological significance in differentiating community patterns. The occurrence of maximum significant indicator species in intermediate rankings (1–3, 4–6) explicit the considerable extent of habitat disturbance on one hand and relatively good tolerance of these species on the other hand.

Shows significance of Indicator Species across Ranking Groups based on p-values in the Gujranwala Forest Division. Ranking 0 lacked strong indicators, ranking 9–10 have fewer indicator species, ranking 7–8 have a few weaker indicators but ranking 1–3 and 4–6 had the majority of the important indicator species (p ≤ 0.05) shown by red color. This highlights the ecological importance of intermediate groups in defining community composition.

Seventy-one (71) plant species identified as indicator species are represented in terms of IVI by using heat maps. Relationships among sites and plant species were shown on each axis using heatmaps. Heat maps are an effective tool for quickly making decisions and displaying enormous amounts of data in a small figure. In a heatmap, colours stood for varying intensities or IVI values. Cooler hues, like olive or dark green, generally indicate lower IVI levels or less intensity. Warmer or brighter hues, such as red, orange or yellow, indicate greater intensity or higher IVI values (Fig. 9) (Supplementary Table S4 online).

Heatmap showing the Importance Value Index (IVI) of native species across riverine forest sites (KG1, KG2, QJS1, QJS2, TFU1 and TFU2). Cooler hues, like olive or dark green, generally indicate lower IVI levels or less intensity. Warmer or brighter hues, such as red, orange, or yellow, indicate greater intensity or higher IVI values. Riverine forests’ ecological diversity and site-specific species dominance are reflected in the pattern.

Discussion

Riverine plants serve as biological processors of terrestrial-aquatic interfaces and are sensitive to a variety of environmental gradients caused by climatic processes, hydrological modifications, sediment and nutrient input from floodplains, land-use types, physical habitat impairment and other human disturbances. The findings showed that land use, topography and habitat degradation had a significant impact on the floristic composition and quality of riverine vegetation in the River Punjab and its tributaries56.

Plans and activities for conservation can be created using the unique image of floristic health that floristic diversity offers53. A thorough understanding of the plant communities in a given area can be developed by vegetation analysis57. The regional patterns of species richness are influenced by a wide range of interrelated elements, such as terrain, elevation, competition, species pool, species dynamics and human activities58,59. Within the floristic composition of the Riverine Forest in Gujranwala Division, there were 110 plant species spread throughout 94 genera and 36 families. Because of physical features, distinct microhabitats and biological zonation, the research region’s vegetation was found to be highly diversified. In contrast to our study, reported a greater number of plant species (198) from the Pakistani Himalayan Naran valley forest, but they were dispersed among fewer families60. Similarly, from the Ropa-Giavung valley in the cold deserts of District Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, India, 160 vascular plant species belonging to 51 families were reported42,61. Although we found fewer species than some other studies, we also found more families and genera’s, which could be a significant finding for the analysis of biodiversity in these areas. The distribution of species is asymmetrical, with only five families accounting for half of the known flora. The three most prominent families are Asteraceae (16 species), Fabaceae (12 species), and Poaceae (10 species). The plant species of the Asteraceae family have a wide range of habitats because of their diverse ecological amplitudes in the Indian region of Kashmir Himalaya reported similar results13,50,62,63. This indicates that the family has a high degree of environmental and temperature adaptation61,62,64. The wide range of families found in the area indicate different distributions of flora, which can be attributed to differences in life span, morphology, microhabitat, and dynamic ecological niche53,65.

In the present study, Solanum was the most prevalent genus demonstrating its high ecological adaptation and resilience to regional environmental pressures. Genera such as Acacia, Abutilon, Chenopodium, Eucalyptus, Ficus, Lantana, Morus, Oxalis, Polygonum., Ranunculus, Salix, Sida, Verbena and Zizyphus were represented by two species each, found to be dominant, reflecting their wide ecological amplitude and ability to tolerate disturbed environmental conditions These dominating genera were important markers of the dominant habitat conditions, having a significant impact on the distribution of species and the general structure of the vegetation66. Nonetheless, a significant pproportion of taxa that are habitat-specific or have limited distributions were highlighted by the large number of monotypic genera (78). Findings from other semi-arid and subtropical forest ecosystems, where disturbance and environmental stress favour domination by resilient species, are consistent with this dominance pattern, which is characterized by few rich and many monotypic genera67. This dominance pattern with few rich and many monotypic genera thriving and the majority of species exhibiting restricted distribution, suggests that the forest ecosystem is under ecological stress. Thus, to preserve floristic variety and stop the future decline of less competitive or habitat specific taxa, cautious management and restoration techniques are required68.

The growth form is a quantitative parameter that may be used to compare geographically dispersed plant habitats and is believed to be a potential indicator of the current environmental circumstances69. The percentage of trees (23.63%) relative to shrubs (6.36%) in the study area indicates how well a forest ecosystem is able to function70,71. In our floristic research, similar to other regions of the North western Himalaya, Herbaceous species (66) make up the majority of the habitat50,72,73,74.

In our findings, therophytes (36.36%) ranked first followed by phanerophytes (31.81%), chamaephytes (15.45%), hemicryptophytes (11.81%), geophytes (3.63%) and helophytes (1%). Therophytes function as an indicator of the impact of human activity and are generally associated with adverse dry environmental conditions73,74,75,76. The results of this study were in agreement with those who also reported that therophytes predominated in their respective fields of study74,75,77,78. These conclusions are further supported by research conducted in other Himalayan forests79. Based on the variety of species present in the forest ecosystems of various geographic regions, certain habitats are better adapted for plant development than others80. Because of changes in plant species pools, habitats and land use patterns brought about by human activity, entire natural forest habitats run the danger of becoming patchy and tarnished81,82,83. The current study discovered that Riverine Forest ecosystems supported the greatest diversity of species when compared to other types of habitats. Our results are corroborated by two Pakistani researchers who discovered the greatest species variety in a natural forest context84. Local species richness is controlled by a variety of biological processes, such as biotic and abiotic filters. Susceptibility to disturbances is also significantly impacted by forest management techniques linked to changes in plant composition and structure85.

During our study, we found 40 exotic and 70 native species in the riverine forests. The proportion of native species was highest in the TFU forest (68%) while the highest proportion of exotic species was found in the QJS woodland (36%). These figures are similar to those reported from the Himachal Pradesh woods in India86. The most common exotic species included trees and shrubs like L. montevidensis, U. lobata, A. bidantatum, E. camaldulensis, L. leucocephala and herbs such as P. hysterophorus, S. marianum, D. innoxia, C. arvensis, A. conzyoides, C. vialis and C. rotundus. Likewise, D. sisso, E. suberosa, W. fruiticosa, B. ceiba M. azedarach, B. papyrifera, F. carica, F. virens, M. alba, M. nigra T. aphyla, S. alba were found as common native species in the riverine habitats83. Species with broad niches that can get through these filters are more likely to overwhelm newly formed ecosystems if they are disturbed.

It is frequently preferred to just include trees and shrubs when evaluating the quality of forests through ordination since these woody elements represent the long-term structural and compositional integrity of forest ecosystems. Over a long period of time, trees and shrubs can integrate environmental variables and disturbance histories because of their deeper root systems, longer life spans, and stronger interactions with environment gradients67,87. On the other hand, herbaceous species, which might mask long-term ecological patterns, are transient and react quickly to brief changes in elements like grazing, canopy gap and rainfall88,89. Thus, ordinations based on woody layer are more appropriate for assessing forest integrity and successional stage since they more accurately reflect long-lasting gradients of species composition, dominance and habitat quality90. So, focusing on trees and shrubs supports more trustworthy management and conservation interpretations and offers a better grasp of the underlying environmental gradients that characterize forest quality.

Ordinance approaches proved beneficial in characterizing the variety of species and habitats in space and time. Further confirming our findings is FQI based PCA on the preferences of woody plant species for their riverine habitats. The PCA ordination makes it simple to discern the distinct community composition of the QJS and TFU sites from that of the KG sites. The fact that KG sites are grouped along the negative side of PC1 and have greater PC2 values suggests that they are structured by a different set of ecological traits than the other sites. The stronger floristic similarity between QJS and TFU is demonstrated by this pattern, which is influenced by species that are either absent or less prevalent in KG. Overall, the PCA demonstrates how species-specific interactions impact compositional divergence, with KG indicating a unique floristic assemblage and QJS and TFU exhibiting overlapping ecological groups. In our study, the presence of S. cumini, B. ceiba, B. papyrifera, P. serratifolia and A. modesta and W. heynei positively associated with PC2 while S. alba, T. aphyla, P. serratifolia, W. fruiticosa, F. virens, F. carica, Z. nummularia, A. nilotica and A. lebbeck were negatively associated with PC2. On the other hand, B. papyrifera B. ceiba, S. alba, P. serratifolia and A. modesta has positive association with PC1 while S. cumini, T. aphyla, W. fruiticosa, F. virens, F. carica, Z. nummularia, A. nilotica, W. heynei and A. lebbeck were negatively associated with PC1. The Biplot shows that PC1 and PC2 representing the most variation of 50.03% and 29.95% respectively, of the difference in woody species (trees and shrubs) and their influence on the forest health.

Out of 110 species that have been documented, 71 indicator species fall between the 0 to 10 ranking range. The indicator species analysis revealed that groups 0 lacked strong indicators, while groups 1–3 and 4–6 had the most significant indicator species (p ≤ 0.05). Overall, the distribution of low p-values across groups emphasizes how indicator species linked to intermediate ranks best describe community identity, highlighting their ecological significance in differentiating community patterns. All types of habitats were found to contain one or more indicator species that resembled those reported in terms of their presence in various habitats/plant communities57,84. A heat map is a useful tool for making quick judgments and visualizing data. The native species in riverine forest sites (KG1, KG2, QJS1, QJS2, TFU1, and TFU2) have been displayed in Fig. 9. At QJS2 and TFU2, species like O. corniculata and C. procera exhibit higher IVI, whereas species like S. cumini and R. sceleratus consistently display lower IVI.

Cluster analysis dendrogram reflects close ecological relationships between QJS and TFU forests while KG forest being a separate distinct cluster. This similarity between QJS and TFU sites may be due to similar anthropogenic pressures like nearness to human settlements and cattle farms, grazing, wood harvest practices etc. Due to its remote location on river bank, KG forest seems under very little human interventions. This may be a supporting factor towards its unique floristic composition. Other factors may be nutrient enrichment, dissemination of propagules, invasion of new species through flood water and a good administrative role of forest crew.

In this study, a method was employed to integrate approaches for identifying environmental factors and links that affect the spatial breadth of plant communities and floristic quality. The FQI is a sensitive measure of changes in plant species composition and provides information about the state of an ecosystem’s processes and biotic interactions17,56,57. The findings showed that KG had the highest (27.83) FQI value followed by QJS (26.11) and TFU woodland had the lowest (23.35). The overall mean FQI value for all the forest studied was calculated as 25.31. FQI values for forests with scores ranging from 10 to 80 were reported51. FQI values of 37.53 were obtained from the disturbed Silica Sand Quarry Bog and Flatiron Lake Bog, respectively91,92. When compared to other indices based on species richness, the “C values” and FQI scores are more superior since they are species-specific and based on the fidelity of plant species93. Trees and shrubs like L. montevidensis, U. lobata, A. bidantatum, E. camaldulensis, L. leucocephala, and herbs like P. hysterophorus, S. marianum, D. innoxia, C. arvensis, A. conzyoides, C. vialis, and C. rotundus that can withstand degraded habitats, are also a part of this riverine vegetation corridor. With the significant loss of riverine vegetation and fundamental ecosystem services, the ecological integrity of these forests has been seriously compromised. The findings indicate a correlation between mean value of conservatism coefficient (C) and increasing levels of human interference15,18,19,21,23,94.

The forested riparian region under study had a Floristic Quality Index (FQI) of 25.31 indicated moderate floristic quality and some how appeared degraded when compared to mesic riparian forests and high-quality remnant wetlands, where FQI values frequently exceed 30. Nonetheless, the measured FQI is similar to or somewhat higher than that of riparian forests embedded in savanna and semi-arid matrices indicating that the forest community maintains a high level of ecological integrity. Arid Nevada riparian systems95 display low species richness and discontinous canopy cover as a result of water limitation, whereas riparian forests in semi-arid Brazil96 and Mediterranean Spain97 display moderate vegetation quality under severe hydrological stress. Similarly, FQI values for Pakistani riparian and wetland vegetation ranged from 18 to 25, indicating agricultural and urban land use disturbance98 Similar trends have been seen in southwestern Nigerian savanna-matrix riparian forests, where diversity indices (H′ = 1.9–2.5) indicate a moderate level of floristic richness under human impact99. Therefore, a FQI of 25.31 in the current semi-arid forest would indicate a refugial community that, in spite of local hydrologic and human-induced limitations, maintains a number of conservative species. Regional C-value assignment, sample intensity, invasive cover, and hydrologic modification should all be carefully taken into account when evaluating such ratings. In order to improve mean C and native species richness over time, management should place a high priority on re-establishing natural flow regimes, managing invasive species, and buffering riparian edges.

Plant species with a preference for severely degraded environments caused by either agricultural operations or sand mining activities from the riverbank predominated in the riverine forests with lower FQI values. The fact that the research region comprises of riverine forests suggests that there may be more anthropogenic disturbances there, which could account for the low floristic index values. A relatively higher FQI value of KG forest exhibits less disturbance and good ecosystem health as compared to QJS and TFU forests. This supports the results of indicator species analysis where species with intermediate ranking (1–3 & 4–6) prevail the area with moderate tolerance of disturbance. It also indicates that if this disturbance continues, there will be more invasion of exotic species replacing the native ones. The quantity, frequency, and intensity of human stressors such as erosion, flooding, grazing, fuel wood, forest fires, cutting, and construction activities along the banks of rivers may alter the biotic communities’ composition and have an effect on the quality of the vegetation100. Surface water quality and the organization of native riverine communities are influenced by physical environment101.

Anthropogenic disruptions are sneaky elements that alter the species composition of riverine environments102. The findings of this study reveal the presence of higher numbers of native and disturbance-sensitive plant species in the selected riverine forests. The forests associated with agricultural and urban land-use types are highly susceptible to colonization by non-native plants and plant species of low conservancy attention, as in the case of TFU. If exotic species displace native species, the effects on the natural flora could be more severe. Our study is further supported by the FQI based results in another study conducted in India43 in which significant pressures from anthropogenic activities such as agriculture and deforestation, leading to the proliferation of non-native species. The floristic quality of riverine habitats and the structure and function of plant communities may be impacted by land use94,103. In current study, the exotic plants made up about 36% of all plant species. Exotic species fare better in artificial conditions than in ecosystems of slightly fragmented forests104 because of their more phenotypic flexibility105. So, they are able to settle in disturbed habitats more skilfully than native species106. Thus, FQI value(s) of our study suggest contradictory results to our hypothesis i.e., “riverine woodland areas are not vulnerable to the influx of exotic species and disturbances”. This means these forests are facing threats and are not in good state of their normal health. Their disturbance is setting up the conditions for invasion of exotic species.

Limitations

This study was performed using FQI for evaluation of ecological heath of selected riverine forests within Forest Division Gujranwala. It has certain limitations:

-

1.

The temporal scope of this study is confined to 2022–2024 and spatial scope is restricted to 3 riverine forests i.e., TFU, QJS and KG. It may not capture long term ecological dynamics of the plant communities in the area due to abrupt climatic changes, floods and habitat degradation.

-

2.

Any physio-chemical analyses of abiotic factors were not included in our study because our study was based on ecological correlations of plant communities with disturbance patterns. The assessment of parallel variability of these abiotic factors with plant communities and disturbance gradients may provide more insights to future research.

-

3.

Although we have thoroughly explored the area, however, our floristic list may underrepresent some ephemeral species diversity especially growing in rainy season during which the area is not accessible.

-

4.

While handling these constraints we have tried our best to present a balanced perspective of ecological health status of these forests based on FQI. Future research may include remote sensing, genetic analysis and long term, all season monitoring strategies to improve the health of these precious forest resources.

Conclusion and implications

The conclusion of current work shows that even naturally reserved forest ecosystems are vulnerable to invasions and threats which disrupt their ecological health. When considering the temporal as well as the spatial elements of riverine vegetation, the FQI method will support threatened species conservation and long-term site monitoring. Comprehending the impact of disturbances on forests and monitoring the potential consequences of land use and climate change on disturbance regimes are crucial aspects of adaptive management. In the ranking groups, the study finds key indicator species that can assist decision makers in developing more targeted conservation policies and enhancing ecosystem and landscape management. This type of data is necessary to initiate management actions and achieve particular objectives. The baseline data from this study will be useful to researchers, policymakers, land managers, and the local community in documenting, maintaining, and preserving the area’s vegetation diversity. By forecasting the state of the forest ecosystem, the findings could be useful in the appraisal and assessment of ecosystem products and services in the riverine forests. Furthermore, the study may be a useful choice for the restoration of this region’s degraded ecosystems as well as the development of scientifically supported management methods because it employs an indicator species technique to examine species attributes.

Recommendations

This work suggests some recommendations:

-

1.

FQI based forest management road map, involving “controlling before the disruption” strategy, should be established to monitor health status of the given forest and to respond various threats and disturbances.

-

2.

Introduction of exotic plants such as A. bidantatum, E. camaldulensis, P. deltoides, S. babylonica, L. montividensis, U. lobata, and L. leucocephala should be legally prohibited unless their ecological validation in these forests.

-

3.

The forest habitat restoration strategies must be accompanied by reintroduction of native species such as D. sisso, E. suberosa, W. fruiticosa, B. ceiba M. azedarach, B. papyrifera, F. carica, F. virens, M. alba, M. nigra, T. aphyla, W. heynei, Z. nummularia and S. alba etc.

-

4.

Human driven activities near or within riverine forests like sand mining, grazing, wood cutting, land grabbing and frequent tourist flow should be decreased and controlled by taking proactive steps to protect these ecoregions from future shocks.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Merawi, E. Identification of ecological threats, pressure and their relative severity of Temcha riverine forest, North West, Ethiopisa. Am. J. Agric. For. 4(3), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaf.20160403.12 (2016).

World Bank. Pakistan Floods 2022, Post-Disaster Needs Assessment, The World Bank Report https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4a0114eb7d1cecbbbf2f65c5ce0789db0310012022/original/Pakistan-Floods-2022-PDNA-Main-Report.pdf (2022).

Rizwan, M. et al. Measuring rice farmers’ risk perceptions and attitude: evidence from Pakistan. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 26(7), 1832–1847 (2020).

Ahmad, D. & Afzal, M. Flood hazards and factors influencing household flood perception and mitigation strategies in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27(13), 15375–15387 (2020).

Paudel, S. et al. Nexus between water security framework and public health: A comprehensive scientific review. Water 13(10), 1365 (2021).

UNDP. Project Document, Sustainable Forest Management Project. (UNDP, 2016).

U.S. EPA. Methods for Evaluating Wetland Condition: Study Design for Monitoring Wetlands. EPA-822- R-02-015. (Office of Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2002).

Manning, D. R., Kaye, M. W., Perles, S. J. & Mortensen, D. A. Short-term vegetation responses following windthrow disturbance on preserved forest lands. Forests 9(5), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9050278 (2018).

Gianoli, E. & Escobedo, V. M. Phenotypic plasticity may mediate habitat filtering in a forest edge community. Oikos 130(10), 1788–1796 (2021).

Jamil, M. D. et al. Invasive plants diversity, ecological status, and distribution pattern in relation to edaphic factors in different habitat types of district Mandi Bahauddin, Punjab, Pakistan. Sustainability. 14(20), 13312 (2022).

Khan, N., Ullah, R., Ali, K., Jones, D. A. & Khan, M. E. H. Invasive milk thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn.) causes habitat homogenization and affects the spatial distribution of vegetation in the semi-arid regions of Northern Pakistan. Agriculture 12(5), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12050687 (2022).

Arshad, F. et al. Predicting the suitable current and future potential distribution of the native endangered tree Tecomella undulata (Sm). Seem Pakistan Sustainability. 14(12), 7215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127215 (2022a).

Waheed, M. et al. Grasses in semi-arid lowlands—community composition and spatial dynamics with special regard to the influence of edaphic factors. Sustainability 14(22), 14964 (2022).

Siddig, A. A., Ellison, A. M., Ochs, A., Villar-Leeman, C. & Lau, M. K. How do ecologists select and use indicator species to monitor ecological change? Insights from 14 years of publication in ecological indicators. Ecol. Ind. 60, 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.06.036 (2016).

Wilhelm, G. & Masters, L. Floristic Quality Assessment in the Chicago Region (The Morton Arboretum, 1996).

Swink, F. & Wilhelm, G. Plants of the Chicago Region. 4th ed (Morton Arboretum, 1994).

Herman, K. D., Masters, L. A., Penskar, M. R., Reznicek, A. A., Wilhelm, G. S. & Brodowicz, W. W. Floristic quality assessment: development and application in the state of Michigan (USA). Nat. Areas J. 17(3), 265–279 (1997).

Miller, S. J. & Wardrop, D. H. Adapting the floristic quality assessment index to indicate anthropogenic disturbance in central Pennsylvania wetlands. Ecol. Ind. 6(2), 313–326 (2006).

Nichols, J. D., Perry, J. E. & DeBerry, D. A. Using a floristic quality assessment technique to evaluate plant community integrity of forested wetlands in southeastern Virginia. Nat. Areas J. 26(4), 360–369 (2006).

Jones, W. M. A vegetation index of biotic integrity for small-order streams in southwestern Montana and a floristic quality assessment for western Montana wetlands. Report to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 29 pp. plus appendices (2005).

Andreas, B. K., John, J. M. & James, S. M. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) for vascular plants and mosses for the State of Ohio. Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Division of Surface Water, Wetland Ecology Group, Columbus, Ohio. 219 (2004).

Rothrock, P. E. Floristic Quality Assessment in Indiana: the Concept, Use, and Development of Coefficients of Conservatism. Unpublished Report Prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Taylor University, 2004).

Cohen, M. J., Carstenn, S. & Lane, C. R. Floristic quality indices for biotic assessment of depressional marsh condition in Florida. Ecol. Appl. 14(3), 784–794 (2004).

Northern Great Plains Floristic Quality Assessment Panel. Floristic quality assessment for plant communities of North Dakota, South Dakota (excluding the Black Hills), and adjacent grasslands. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/2001/fqa/fqa.htm (Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page, 2001).

Bernthal, T. W. Development of a Floristic Quality Assessment Methodology for Wisconsin. Unpublished Report Prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region V (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 2003).

Nelson, P. W. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri. 2nd ed. (Missouri Natural Areas Committee, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, 2005).

DuPage County Stormwater Management Committee. Appendix, E. Technical Guidance for the Dupage Countywide Stormwater and Floodplain Ordinance 24 (DuPage County Stormwater Management Division, 1992).

Ladd, D. M. Coefficients of Conservatism for Missouri Vascular Flora (The Nature Conservancy, 1993).

Arsenault, A. & Larocque, G. R. Indicators of forest ecosystem integrity. In Ecological Forest Management Handbook, 338–355 (CRC, 2024).

Kermavnar, J. & Kutnar, L. Mixed signals of environmental change and a trend towards ecological homogenization in ground vegetation across different forest types. Folia Geobotanica. 58(3), 333–352 (2024).

Dinca, L., Crisan, V., Ienasoiu, G., Murariu, G. & Drasovean, R. Environmental indicator plants in mountain forests: A review. Plants 13(23), 3358 (2024).

Alizadeh Shabani, A. Identifying bird species as biodiversity indicators for terrestrial ecosystem management (Doctoral dissertation, RMIT University) (2024).

Looy, K. V. & Meire, P. A conservation paradox for riparian habitats and river corridor species. J. Nat. Conserv. 17, 33–46 (2009).

Magner, J. A. & Vondraceck, B. Grazed riparian management and stream channel response in Southeastern Minnesota (USA) streams. Environ. Manage. 42, 377–390 (2008).

Qadir, A., Malik, R. N. & Hussain, S. Z. Spatio-temporal variations in water quality of Nullah Aik-tributary of the river Chenab, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 140, 43–59 (2008).

Beniston, M. Climatic change in mountain regions: a review of possible impacts. Clim. Change. 59(1–2), 5–31 (2003).

Nasir, E. & Ali, S. I. Flora of Pakistan. Nos. 1-190. Department of Botany, University of Karachi and National Herbarium, PARC, Islamabad (1970–1989).

Ali, S. I. & Qaiser, M. Flora of Pakistan. Nos 194–208 (Department of Botany, University of Karachi and National Herbarium, PARC, 2007).

Ali, S. I. & Nasir, Y. J. Flora of Pakistan. Nos. 191–193. Department of Botany, University of Karachi and National Herbarium, PARC, Islamabad (1990-92).

Ellenberg, D. & Mueller-Dombois, D. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology Vol. 547 (Wiley, 1974).

Clements, F. E. Research Methods in Ecology (The University Publishing Company, 1905).

Ullah, U. et al. A survey of the floristic composition of the Kambat Valley, District Dir Lower, Northern Pakistan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 43(4), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2022.08.002 (2023).

Deenadayal, T. Floristic quality assessment index of plant diversity evaluation in Bolamanadoddi hills Raichur district Karnataka India. Int. J. Plant. Environ. (2025).

Raunkiaer, C. The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography; Being the Collected Papers of C. Raunkiaer 632 (Clarendon, 1934).

Cottom, G. & Curtis, J. T. The use of distance measures in phytosociological sampling. Ecology 37(3), 451–460 (1956).

Daubenmire, R. F. Canopy coverage method of vegetation analysis. Northwest. Sci. 33, 39–64 (1959).

Risser, P. G. & Rice, E. L. Phytosociological analysis of Oklahoma upland forest species. Ecology 49, 1006–1009 (1971).

Andreas, B. K. & Lichvar, R. W. Floristic Index for Establishing Assessment Standards: A Case Study for Northern Ohio (Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station Vicksburg MS, 1995).

Haq, S. M., Calixto, E. S., Rashid, I. & Khuroo, A. A. Human-driven disturbances change the vegetation characteristics of temperate forest stands: A case study from Pir Panchal mountain range in Kashmir Himalaya. Trees For. People. 6, 100134 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2021.100134 (2021).

Haq, S. M., Hamid, M., Lone, F. A. & Singh, B. Himalayan hotspot with Alien Weeds: a case study of biological spectrum, phenology, and diversity of weedy plants of high-altitude mountains in District Kupwara of J&K Himalaya, India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B: Biol. Sci. 91(1), 139–152 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40011-020-01219-6 (2021).

Wilhelm, G. & Ladd, D. Natural area assessment in the Chicago region. In Transactions of the 53rd North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference (ed McCabe, R. E.) 361–375 (Wildlife Management Institute, 1988).

Haq, Z. et al. An evaluation of conservation status and ecological zonation of alnus nitida; a monophyletic species of the sino-Japanese region. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 30(5) (2020).

Haq, S. M., Calixto, E. S., Rashid, I., Srivastava, G. & Khuroo, A. A. Tree diversity, distribution and regeneration in major forest types along an extensive elevational gradient in Indian Himalaya: implications for sustainable forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 506, 119968 (2022).

Ali, S. M. & Malik, R. N. Vegetation communities of urban open spaces: green belts and parks in Islamabad city. Pak. J. Bot. 42(2), 1031–1039 (2010).

Sorensen, T. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biologiske Skrifter. 5, 1–34 (1948).

Lowrance, R., Sharpe, J. K. & Sheridan, J. M. Long term sediment deposition in the riparian zone of a coastal plain water shed. J. Soil Water Conserv. 41, 266–271 (1986).

Chhetri, N. B. K. & Shrestha, K. K. Floristic diversity and important value indices of tree species in lower Kanchenjunga Singhalila ridge Eastern Nepal. Am. J. Plant. Sci. 10(1), 248–263. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2019.101019 (2019).

Rahman, I. U. et al. Ecological gradients hosting plant communities in Himalayan subalpine pastures: application of multivariate approaches to identify indicator species. Ecol. Inf. 60, 101162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.101162 (2020).

Mitchell, J. C. et al. Forest ecosystem properties emerge from interactions of structure and disturbance. Frontier Ecol. Environonment. 21, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee (2023).

Khan, S. M., Page, S., Ahmad, H.A.B.I.B., Shaheen, H.A.M.A.Y.U.N. & Harper, D. M. Vegetation dynamics in the Western Himalayas, diversity indices and climate change. Sci. Technol. Dev. 31(3), 232–243 (2012).

Verma, R. K. & Kapoor, K. S. Plant species diversity in Ropa-Giavung Valley in cold deserts of District Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh. Biol. Forum-Int. J.. 3(2), 34–43 (2011).

Rahman, I. U. et al. Role of multivariate approaches in floristic diversity of Manoor Valley (Himalayan Region), Pakistan. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 17, 1475–1498. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1702_14751498 (2019).

Rashid, I. et al. Railways redistribute plant species in mountain landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 58(9), 1967–1980. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13961 (2021).

Khan, W. et al. Life forms, leaf size spectra, regeneration capacity and diversity of plant species grown in the Thandiani forests, district Abbottabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 25(1), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.11.009 (2018).

Khoja, A. A. et al. Ecological and traditional knowledge of pteridophytes in the western Himalayas. Diversity 14(8), 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080628 (2022).

Zhao, F. et al. Community diversity and composition affect ecosystem multifunctionality across environmental gradients in boreal and temperate forests. Ecol. Ind. 159, 111692 (2024).

Helman, D., Lensky, I. M., Tessler, N. & Osem, Y. A phenology-based method for monitoring woody and herbaceous vegetation in mediterranean forests from NDVI time series. Remote Sens. 7(9), 12314–12335 (2015).

Behera, M. C. et al. Species composition and diversity of plants along human-induced disturbances in tropical moist Sal forests of Eastern Ghats, India. Forests 14(10), 1931 (2023).

Lavorel, S. & Garnier, E. Predicting changes in community composition and ecosystem functioning from plant traits: revisiting the Holy Grail. Funct. Ecol. 16(5), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00664 (2002).

Khan, S. M. et al. Ethnobotanical study of some medicinal plants of Tehsil Kabal, District Swat, KP, Pakistan. Med. Aromat. Plants 4(189), 2167–0412 (2015).

Khan, A. M. et al. Floristic checklist of district Kotli, Azad Jammu & Kashmir. Pak. J. Bot. 47(5), 1957–1968 (2015a).

Dar, J. A. & Sundarapandian, S. Patterns of plant diversity in seven temperate forest types of Western Himalaya, India. J. Asia-Pacific Biodivers. 9(3), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2016.03.018 (2016).

Nafeesa, Z. et al. Observations on the floristic, life-form, leaf-size spectra and habitat diversity of vegetation in the Bhimber hills of Kashmir Himalayas. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41(3), 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2021.03.003 (2021).

Rahman, I. U. et al. Advanced multivariate and computational approaches in agricultural studies. Essentials of bioinformatics, volume III: in silico life sciences: agriculture. 93–102 (2019).

Rahman, I. U. et al. First insights into the floristic diversity, biological spectra and phenology of Manoor Valley, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Botany. 50(3), 1113–1124 (2018).

Vakhlamova, T., Rusterholz, H. P., Kanibolotskaya, Y. & Baur, B. Effects of road type and urbanization on the diversity and abundance of alien species in roadside verges in Western Siberia. Plant Ecol. 217, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-016-0565-1 (2016).

Wali, S. et al. Phyto-ecological study of the forests of Shishi Koh Valley, Chitral, Pakistan. Vegetos 35(4), 1024–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-022-00379-2 (2022).

Asim, Z. I., Haq, F. & Iqbal, A. Phenology, life form and leaf spectra of the vegetation of Kokarai valley, district Swat. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 9, 23–31 (2016).

Sharma, J. & Raina, A. K. Quantitative analysis, distributional pattern and species diversity of Woody plant species of Lamberi Forest Range, Rajouri, J&K, India. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 10(1), 522–527. https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v10i1.1661 (2018).

Medveck´a, J. et al. Forest habitat invasions–Who with whom, where and why. For. Ecol. Manag. 409, 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.038 (2018).

Mishra, C., Prins, H. H. & Van Wieren, S. E. Diversity, risk mediation, and change in a Trans-Himalayan agropastoral system. Hum. Ecol. 31(4), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HUEC.0000005515.91576.8 (2023).

Bhatt, R. P. & Bhatt, S. Floristic composition and change in species diversity over long temporal scales in upper Bhotekoshi hydropower project area in Nepal. Am. J. Plant. Sci. 7(01), 28 (2016).

Haq, S. M., Malik, A. H., Khuroo, A. A. & Rashid, I. Floristic composition and biological spectrum of Keran-a remote valley of northwestern himalaya. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39(5), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2018.12.001 (2019).

Qureshi, R. & Bhatti, G. R. Floristic inventory of Pai forest, Nawab Shah, Sindh, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Botany. 42(4), 2215–2224 (2010).

Seidl, R., Schelhaas, M. J. & Lexer, M. J. Unraveling the drivers of intensifying forest disturbance regimes in Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 17(9), 2842–2852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02452 (2011).

Kohli, R. K., Dogra, K. S., Batish, D. R. & Singh, H. P. Impact of invasive plants on the structure and composition of natural vegetation of northwestern Indian Himalayas1. Weed Technol. 18(sp1), 1296–1300. https://doi.org/10.1614/0890-037X(2004)018[1296:IOIPOT]2.0.CO;2 (2004).

Gilliam, F. S., Turrill, N. L. & Adams, M. B. Herbaceous-layer and overstory species in clear‐cut and mature central Appalachian hardwood forests. Ecol. Appl. 5(4), 947–955 (1995).

Spicer, M. E., Nair, H. V., Duguid, M. C., Queenborough, S. A. & Comita, L. S. Herbaceous plant diversity in forest ecosystems: Patterns, mechanisms, and threats. Plant Ecol. 222(7), 925–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-021-01134-1 (2021).

Sheng, Q., Dong, L., Liu, Z. & Liu, Z. Driving forces of herbaceous species diversity in natural broadleaf forests from Maoershan, Northeast China. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1503811. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1503811 (2024).

Miller, D., Higuchi, P. & Blum, C. T. Indicator species and characterization of the woody and herbaceous layer in an Atlantic Forest ecotone area at the Paraná portion of Serra do Mar. Rodriguésia. 74, e01542021. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-7860202374010 (2023).

Andreas, B. K. & Bryan, G. R. The vegetation of three Sphagnum-dominated basin-type bogs in northeastern Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 90(3), 54–66 (1990).

Andreas, B. K. & Host, G. E. Development of a sphagnum bog on the floor of a sandstone quarry in northeastern quarry in northeastern Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 83(5), 246–253 (1983). http://hdl.handle.net/1811/22962

Bowers, K. & Boutin, C. Evaluating the relationship between floristic quality and measures of plant biodiversity along stream bank habitats. Ecol. Ind. 8, 466–475 (2008).

Lopez, R. D. & Fennessy, M. S. Testing the floristic quality assessment index as an indicator of wetland condition. Ecol. Appl. 12(2), 487–497 (2002).

McGwire, K. C. Optimized stratification for mapping riparian vegetation in arid and semiarid environments. Remote Sens. 11(14), 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11141638 (2019).

de Lacerda, A. V. & Barbosa, F. M. Riparian vegetation structure in a conservation unit in the semi-arid region of Paraíba, Brazil. Floresta Ambiente. 27(2), e20180240. https://doi.org/10.1590/2179-8087.024018 (2020).

Magdaleno, F. & Martínez, R. Evaluating the quality of riparian forest vegetation: the riparian forest evaluation (RFV) index. For. Syst. 23(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.5424/fs/2014232-04488 (2014).

Malik, R. N., Husain, S. Z. & Ahmed, S. S. Floristic quality assessment and its application in riparian/wetland vegetation in Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 44(SI1), 187–197 (2012). https://www.pakbs.org/pjbot/PDFs/44(SI1)/27.pdf

Borisade, T. & Odiwe, A. Floristic composition, structure and diversity of riparian forests in southwestern Nigeria: conservation is inevitable. Nord. J. Bot. https://doi.org/10.1111/njb.03723 (2023).

Barbour, M. T., Gerritsen, J., Snyder, B. D. & Stribling, J. B. Rapid bioassessment protocols for use in streams and Wade able rivers: Periphyton, benthic macroinvertebrates and fish, 2nd ed. EPA 841-B-99-002. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Office of Water; 1999).

Swaine, M. D., Adomako, J., Ameka, G., De Graft- Johnston, K. A. A. & Cheek, M. Forest river plants and water quality in Ghana. Aquat. Bot. 85, 299–308 (2006).

Death, R. G. The effect of habitat stability on benthic invertebrate communities: the utility of species abundance distributions. Hydrobiologia 317, 97–107 (1996).

Shandas, V. & Alberti, M. Exploring the role of vegetation fragmentation on aquatic conditions: linking upland with riparian areas in Puget Sound lowland streams. Landsc. Urban Plann. 90, 66–75 (2009).

Davidson, A. M., Jennions, M. & Nicotra, A. B. Do invasive species show higher phenotypic plasticity than native species and if so, is it adaptive? A meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 14(4), 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01596 (2011).

Gonz´alez-Moreno, P., Pino, J., Gass´o, N. & Vila, M. Landscape context modulates alien plant invasion in Mediterranean forest edges. Biol. Invasions. 15(3), 547–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0306 (2013).

Kleunen, M. V., Weber, E. & Fischer, M. A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecol. Lett. 13(2), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01418 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Authors are very thankful to Department of Botany, Government College University, Lahore for providing need¬ful facilities and assistance to complete this research work. We sincerely acknowledge the valuable assistance of the field botanists (Pr. Dr. Zaheer ud din Khan, Dr. Sohaib Muhammad, Dr. Andleeb Anwar Sardar, Mr. Muhammad Tayyab and Mr. Ali Ahmad) in species identification and assessing of CC value for FQI.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the award of funds from ORIC (Office of Research Innovation & Commercialization) Government College University, Lahore to conduct the PhD research experiment. No funds were granted for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saima Khalid: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal data analysis, Validation, Writing - original draft. Sohaib Muhammad: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Ali Ahmad: Data curation, Formal data analysis. Zaheer-ud-din Khan: Data curation, formal data analysis. Muhammad Khalil: Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics declarations

The experiment complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalid, S., Muhammad, S., Ahmad, A. et al. Spatial assessment of ecological health of riverine forest ecosystem using Floristic Quality Index. Sci Rep 15, 43987 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27647-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27647-w