Abstract

The well-known topic of crisp graph planarity is contrasted with the more new and thoroughly studied field of planarity inside a fuzzy framework. In cubic fuzzy domain, cubic multisets with interval and fuzzy number to capture vagueness. Cubic fuzzy graphs (CuFGs) are structures which use cubic multisets to represent membership of vertices and edges. The interval represents a continuous process, whereas the point defines a specific process. Thus, cubic fuzzy graphs perform better than both interval valued graphs and fuzzy graphs as they indicate the level of participation of vertices and edges enabling management of uncertainty and ambiguity in interval valued fuzzy graphs (IvFG) and fuzzy graphs (FGs). The properties and characteristics of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs is investigated in this article, diving into a variety of fascinating elements of these topics. Cubic fuzzy graphs (CuFGs) can be created by removing individual vertices or edges from cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs (CuFOSs). The study also includes examples of maximal and maximum cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs obtained by removing both vertices and edges. Furthermore, the definition of cubic fuzzy dual graphs (CuFDGs), which are formed from cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs (CuFGs) is presented and underlying relationship among these is explored. A practical application of this work is found in human face shape recognition, where cubic fuzzy graphs (CuFGs) offer a powerful framework for modeling facial geometry. It is observed that by accommodating uncertainty in facial feature positions and relationships, CuFGs enable more accurate recognition in complex biometric identification tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Planarity in a fuzzy framework, a recent domain but already being formed and extensively studied field, is compared to the classic idea of crisp graph planarity. Among several fuzzy graph models, cubic fuzzy graphs outperform both interval-valued fuzzy graphs and normal fuzzy graphs, given that they take into consideration a level of involvement for vertices and edges in their two forms. Moreover, cubic fuzzy graphs surpass traditional fuzzy models when navigating ambiguity and uncertainty. A point in a cubic fuzzy graph depicts a single or unique activity, while an interval implies a continuous process, making cubic fuzzy graphs a more versatile tool for complicated network analysis. A mathematical method for handling ambiguity and imprecision, fuzzy set theory was initially put forward by Lotfi A. Zadeh1 in 1965, which was supposed to improve traditional set theory by enabling things to have various degrees of membership in a set rather than just belonging or not belonging. Kaufmann2 explored fuzzy relations and fuzzy sets in great detail, and ten years after the release of the article “Fuzzy sets” by Zadeh et al.4, Rosenfeld3 proposed fuzzy graphs. After these reports, Abdul-Jabbar5 brought through the concept of fuzzy dual graphs, which builds on the present knowledge of fuzzy graphs. Akram et al.6 developed Pythagorean fuzzy multigraphs and planar graphs and investigated their properties. Along with the concepts of isomorphism, weak isomorphism, and co-weak isomorphism in connection with Pythagorean fuzzy planar graphs, they also investigated non-planar Pythagorean fuzzy graphs. In addition to presenting a useful application of these ideas, this work demonstrated an important connection between Pythagorean fuzzy planar graphs and their duals. Likewise, Alshehri et al.7 established the concepts of intuitionistic fuzzy multigraphs, intuitionistic fuzzy planar graphs, and intuitionistic fuzzy dual graphs and evaluated their properties as well as the isomorphism between them. While demonstrating that properties from crisp graph theory are not always appropriate for fuzzy graphs, Bhattacharya8 investigated the relationship between fuzzy groups and fuzzy graphs, integrating concepts like eccentricity and centre and demonstrated that properties pertaining to crisp graph theory are not always applicable for fuzzy graphs. The work further additional bridges and cut nodes in fuzzy graphs, accompanied and definition.

To address concepts like complete and connected dominance, as well as implications and theorems regarding domination in fuzzy graph products, Somasundaram9 examined the dominating characteristics of a number of fuzzy graph operations, including union, join, composition, and Cartesian product. The intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS) was first presented by Atanassov10 in 1983 as an extension of Zadeh’s fuzzy set theory. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets are more sophisticated than classical fuzzy sets because they have both a membership and a non-membership function, as well as an extra layer of reluctance or uncertainty. This enhances IFS’s adaptability while handling vague and unclear instructions. Additionally, intuitionistic fuzzy sets and intuitionistic graphs were advanced by Shannon and Atanassov11.To represent ambiguity better in membership, Yager12 developed Pythagorean fuzzy subsets, which are identified by Pythagorean membership grades that comprise both a strength of commitment and a direction of commitment. The author additionally further addressed operations on these subsets, such as negation and basic set operations, and contrasted them with intuitionistic fuzzy subsets. On another hand, Pal et al.13 presented fuzzy tolerance graphs, which extend the concept of regular tolerance graphs by introducing fuzzy relations to reflect ambiguity in vertex connections. Bipolar fuzzy graphs were examined by Akram et al.14, who concentrated on characteristics, distance measures, and applications in decision-making across various domains. They looked at regularity, irregularity, and the connections between various bipolar fuzzy graphs and digraph forms.

In order to improve graph theory, McAllister15 created fuzzy intersecting graphs, which model systems, where conventional random assumptions might not hold. Two edge types that are significant and effective in fuzzy planar graphs are presented by Samanta et al.16, where also compared to Kuratowski’s graphs. Additionally, the concept of strong fuzzy planar graphs was discussed along with their applications in pipeline and subway tunnel modelling, as well as pictorial depiction. Nirmala17 proposed special planar fuzzy graph configurations, emphasising Hamiltonian fuzzy graphs and their properties, outlining the various algorithms and concepts in fuzzy graph tsheory, with an emphasis on their computational complexity and applications. The author concluded that the Hamiltonian circuit problem for planar fuzzy graphs is NP-complete. In 1930, Kuratowski18 presented some remarkable findings on planar graphs. Samanta et al.19 developed fuzzy multigraphs, fuzzy planar graphs, and fuzzy dual graphs. They also defined the concepts of strong fuzzy planar graphs and fuzzy planarity value, as well as the properties and relationships among these graph types. Samanta et al.20 intriguing theorems concerning fuzzy planar graphs are investigated, and novel ideas involving fuzzy planar graphs were introduced, with a focus on the fuzzy planarity value’s characteristics. In order to facilitate approximation reasoning in fuzzy logic, Zadeh4 characteristic value of introduced linguistic variables, or variables with values that are words or sentences. Self-centred interval-valued fuzzy graphs were described by Akram et al.21, that focused on their characteristics and metric aspects, including eccentricity, radius, and diameter, as well as the benefits of interval-valued fuzzy graphs over conventional fuzzy graphs in terms of demonstrating flexibility and uncertainty in a variety of applications.

In addition to describing various interval-valued fuzzy graph types, including balanced and highly irregular variants, and analyzing their properties and relationships to intuitionistic fuzzy graphs22, further established necessary and sufficient conditions for the equivalence of certain irregular interval-valued fuzzy graphs. Related concepts, encompassing interval-valued fuzzy faces, interval-valued fuzzy dual graphs, and strong edges, have been proposed by Pramanik et al.23. Researchers also defined the "degree of planarity" as a way to determine how planar an interval-valued fuzzy graph is. The idea of internal and external cubic sets, together with operations like P-union and R-intersection, were introduced by Jun24. The author strengthened the significance of these operations in fuzzy mathematics through investigation involving their characteristics and the circumstances which lead to internal or external cubic sets. Sable cubic sets were first introduced by Muhiuddin25. Rashid26 introduced cubic graphs and their uses. Yager27 introduced the concept of multisets, or bags, set of collections where component frequency matters. Furthermore, established the application of operations like intersection, union, and addition on bags in relational databases and fuzzy logic. In addition to discussing the properties and applications of cubic graphs, such as the definition of direct and strong products, Rashmanlou28 developed a fuzzy cubic organizational model for decision support systems and emphasized the benefits of cubic graphs over fuzzy graphs in a range of computer science applications. In contrast to earlier principles, Muhiuddin29 brought an entirely novel approach to cubic graphs, examined their properties and applications, and demonstrated their value for traffic flow optimization. For a generic approach to handling imprecise information, Gulistan30 suggested neutrosophic cubic graphs, highlighting their advantages over fuzzy sets and demonstrating their use in a range of sectors. As a generalization of fuzzy and bipolar fuzzy graphs, Jan31 described cubic bipolar fuzzy graphs (CBFGs), examining their characteristics, functions, and utilization in social networks. By expanding neutrosophic cubic graphs, Gulistan30 created new neutrosophic cubic graph structures and investigated the manner they functioned and how they were employed in decision-making scenarios.

In his exploration of cubic planar graphs, Muhiuddin29 introduced new ideas and theorems pertaining to these graphs while emphasizing their benefits over interval-valued and fuzzy graphs in handling uncertainty and describing participation levels. Cubic intuitionistic planar graphs and their utilization in runway traffic management. Fang32 had emphasizing the features and applications of these graphs in graph theory. After establishing the key concepts planar graphs, m-polar fuzzy multi-sets, and strong edges. Ghorai et al.33 proceeded on to investigate the properties of m-polar fuzzy multi-graphs such that they circumvent edge crossings in a planar graph. For a number of reasons, edge crossings are troublesome. Importantly, this study shows how to model uncertainties in graph architectures for practical use. They defined m-polar fuzzy multi-graphs employing planar graphs, strong edges, and m-polar fuzzy multi-sets. Examines a variety of features associated with m-polar fuzzy planar networks, such as the total number of intersection places between strong and significant edges and the planarity value34. An approach for splitting large-scale integration networks into fuzzy planar subgraphs. They use vertex and edge deletion procedures to generate fuzzy planar subgraphs. Along with addressing the idea of thickness value in fuzzy networks, they additionally invented a novel Planar Partition subgraph approach that boosts the efficiency of creating these subgraphs. As illustrated by35, the results are applied to network partitioning in VLSI design and given as examples. In addition to introducing ideas like partially and fully edge regular cubic graphs and exploring the consequences in modeling trip time in networks, Krishna et al.36 evaluated the characteristics of cubic graphs, concentrating on edge regular, strongly regular, and bi-regular types.

The significance of these concepts in enhancing system accuracy and tackling urbanization challenges was underlined by Jiang et al37., where in new ideas of vertex covering in cubic graphs, emphasis on strong vertex covering and independence, as well as their potential uses in modeling uncertainty and optimizing actual-world issues such as monitoring stations and urban service distribution has been reported. Greenlaw38 wrapped numerous examples of classical results in graph theory pertaining to cubic graphs, emphasized the intricacy of problems involving them, and talked about their characteristics and historical significance. He additionally offered a new algorithm for the maximal matching problem. In order to efficiently generate all non-isomorphic linked cubic graphs, Brinkmann39 introduced a new algorithm that is more than four times faster than existing techniques. The implementation is intended to facilitate the study of particular graph classes, such snarks, and permits constraints based on girth. Fuzzy outerplanar graphs were first presented by Deivanai et al.40,41 has been presented the extension of traditional crisp graphs that represent ambiguous relationships by including various membership levels. The characteristics of maximal and maximum fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs were also studied, as well as the uses of these graphs in network modeling, specifically in transport networks, then introduced bipolar fuzzy outerplanar graphs, extending classical outerplanar graphs with bipolar fuzzy set theory to model uncertainty and dual membership values, and it’s explored their structural properties, dual graphs, vertex/edge deletion subgraphs, and applies the concepts to image shrinking. Further developed m-polar fuzzy outerplanar graphs (mPFOGs) and studies their properties, subgraphs, and duals, applying them to optimize one-way bypass road networks for better traffic flow and reduced accidents by42. Recently developed interval valued fuzzy outerplanar graphs (IVFOGs) as a framework for designing bypass road networks under uncertainty, by applying vertex and edge deletions, it optimizes traffic flow, reduces congestion, and enhances real-world transport planning by43. Muhiuddin44 introduced cubic Pythagorean fuzzy graphs (CuPFGs), combining cubic and Pythagorean fuzzy sets to better handle uncertainty in graph structures. It defines their properties, operations, and preference relations, and demonstrates their effectiveness in multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) through practical applications.

Xie et al.45 developed an innovative face recognition system that uses a 2D face shape model and a block-based equalization identification rates, making facial images more visible in typical illumination. By contrasting distinctive registration methods, 3D facial features, and decision-level fusion approaches, Gökberk et al.46 established a thorough analysis of 3D shape-based face recognition. It demonstrated that rigid registration and surface normals produce higher recognition accuracy, and fusion schemes strengthen performance when individual classifiers remain merely successful. Using a shape from recognition technique that uses neural networks to map face parts under different lighting conditions and positions, Nandy and Ben-Arie47 presented a framework for 3D face shape recovery. The method’s ability to reliably recover facial structures is demonstrated by the results, which show strong performance with an average reconstruction error of less than 3%. Using registered point clouds, Irfanoglu et al.48 introduced a unique 3D face recognition technique that improves identification accuracy by creating dense correspondences using thin plate spline warping and automatic landmarking. According to experimental data, the suggested Point Set Distance strategy performs better than conventional approaches, obtaining high recognition rates with less computational complexity. The main face recognition techniques, including PCA, ICA, LDA, Elastic Bunch Graph Matching, AAM, and 3D Morphable Models, were reviewed by Lu49. They were divided into appearance-based and model-based approach and the difficulties posed by real-world facial variations. Evaluation results and future research directions were also presented. Trsoje and Bülthoff50 explored into how human face recognition is impacted by various viewing angles and facial surface characteristics. The findings indicate that the learning view and face texture have a major impact on recognition, with symmetry being particularly important for features with shading.

Rao et al.51 introduced the use of the q-rung orthopair fuzzy Zagreb index to improve decision-making strategies. Similarly, Kosari et al.52,53 studied topological indices in fuzzy graphs with direct applications to decision-making problems, further presented a novel description of perfectly regular fuzzy graphs and highlighted their application in psychological sciences. Further advancements in this direction include the study of interval-valued picture fuzzy hypergraphs for decision making by Khan et al.54, and the application of connectivity indices of cubic fuzzy graphs to identify tsunami danger zones by Shi et al.55. Kaviyarasu et al.56 explored circular economy strategies using t-neutrosophic fuzzy graphs to promote sustainable development, expanding the scope of fuzzy graph applications. On the structural side, Kosari et al.57,58 analyzed the properties of connectivity in vague fuzzy graphs with applications in building university networks and examined domination in vague graphs with applications in medicine. In addition, Shi et al.59 introduced interval-valued picture fuzzy graphs and applied them to the transmission control protocol and social networks.

Several recent studies have also extended fuzzy graph theory in various directions. For instance, vertex connectivity of fuzzy graphs has been explored with applications to social problems such as human trafficking60. Interval-valued fuzzy graphs and their degree-based properties were analyzed in61. Vague graphs have been studied in62, and domination sets in vague graphs with applications were introduced in63. Decision-making frameworks using multi-attribute interval-valued picture (S, T)-fuzzy graphs have been developed in64. Interval-valued picture fuzzy hypergraphs with applications to decision making were proposed in54. Furthermore, new concepts of intuitionistic fuzzy trees with applications were introduced in65.

From literature, it is observed that the traditional idea of outerplanar graphs into the fuzzy and interval-valued domain, has wide scope for research goal of the current work is to investigate and evaluate the structural characteristics and applications of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs. The primary objective of this study is to formally define cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs and examine their properties, with a special emphasis on creating maximal and maximum subgraphs by removing vertices and edges. Furthermore, the concept of cubic fuzzy dual graphs is presented and their connection to the related primal graphs is investigated. Demonstrating the usefulness of these structures in real-world situations, with an emphasis on face shape recognition, is the main objective. Cubic fuzzy graphs provide a strong framework for simulating facial geometry in these kinds of applications, improving biometric system accuracy. We believe cubic fuzzy graphs are better at describing complicated systems with intrinsic ambiguity and imprecision. The abbreviations used in this paper are given in (Table 1).

Motivation of the work

When it comes to resolving real-world issues involving networks, linkages, and relationships, graph theory is essential. Even while they are helpful, traditional crisp graph models frequently fail to capture the ambiguity and uncertainty found in real-world systems. Interval valued fuzzy graphs and intuitionistic fuzzy graphs are some of the models of fuzzy graphs that scholars have created to address this issue. Because they are better at capturing both membership and non-membership degrees, cubic fuzzy graphs have become one of the most potent tools for dealing with uncertainty. In comparison to interval valued fuzzy graphs and fuzzy graphs, cubic fuzzy graphs are better represented since they exhibit the membership degree of vertices and edges in both fuzzy number and interval formats. This greater clarity allows for a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the relationships and uncertainties that determine the graph’s structure. Cubic fuzzy graphs differentiate themselves by having the ability to characterize the membership degree of vertices and edges using intervals and fuzzy integers, respectively. Fuzzy graph planarity, which is crucial for tasks like circuit design, transit networks, and visual data representation, has been at the forefront of current research.

The research area of cubic fuzzy planar graphs continues to remain predominantly unexplored, despite notable advancements in different kinds of fuzzy planar graphs, such as Pythagorean, intuitionistic, and bipolar models. Furthermore, there currently exists not much literature on outerplanarity in the context of cubic fuzzy graphs, even though outerplanar graphs are an extensively researched subclass of planar graphs with practical significance in streamlining complex network structures. There is an obvious gap in the literature because of this. To improve the modeling of complex systems under uncertainty with simplified and computationally efficient structures, this research is driven by the necessity to extend the idea of outerplanarity to cubic fuzzy graphs. The present article intends to make a novel contribution to fuzzy graph theory and offer a fresh approach to modeling in uncertain situations by examining the characteristics, structure, and possible uses of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs.

Novelty of the article

The novelty of this study lies in extending the concept of outerplanarity to cubic fuzzy graphs (CuFGs), a domain that has not been sufficiently explored in fuzzy graph theory. While crisp graph planarity and several fuzzy extensions such as intuitionistic, interval-valued, and bipolar fuzzy graphs have been investigated, cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs (CuFOGs) remain an uncharted research area. The distinctive contributions of this work include:

-

(1)

The study establishes the properties and characteristics of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs, showing how they can be systematically derived from cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs (CuFOSs) by vertex and edge removal.

-

(2)

It introduces cubic fuzzy dual graphs (CuFDGs) within the outerplanar framework and examines their interrelationship with CuFOGs, providing fresh insights into duality in fuzzy settings.

-

(3)

By combining interval and point-based membership representation, CuFGs manage uncertainty more effectively than interval-valued fuzzy graphs (IvFGs) and fuzzy graphs (FGs). This dual representation enables a deeper understanding of ambiguity in networks.

-

(4)

The proposed framework is applied to face shape recognition, where CuFGs model geometric features under uncertainty, offering improved adaptability and accuracy in biometric identification systems.

Overall, this research pioneers the study of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs, enriches fuzzy planar graph theory, and introduces a novel and practically relevant modeling paradigm for complex real-world problems involving uncertainty.

Objective of the study

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the structural properties and characteristics of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs (CuFOGs). Specifically, the work aims to:

-

(1)

Analyze the traits and attributes of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs in comparison with related fuzzy graph.

-

(2)

Examine the formation of cubic fuzzy subgraphs through the deletion of vertices and edges.

-

(3)

Present examples of maximal and maximum cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs.

-

(4)

Explore the construction and interrelation of cubic fuzzy dual graphs derived from cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs.

-

(5)

Demonstrate practical applications, particularly in face shape recognition, where cubic fuzzy graphs provide a robust framework for handling uncertainty in geometric structures.

Preliminaries

Some fundamentals definitions are used in the article are given below.

Definition 1 30

A cubic fuzzy set (CuFS) on a non-empty set \({\mathbb{V}}\) is expressed as

where \(\alpha \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\) and \(\beta \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\) denote the lower and upper bounds of the interval-valued fuzzy membership of \(\mathcal{z}\), and \(\gamma \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\) represents the standard fuzzy membership degree. Thus, \(\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma :{\mathbb{V}}\to [\text{0,1}]\).

The CFS is termed an internal cubic fuzzy set if for every \(\mathcal{z}\in {\mathbb{V}}\), the membership value \(\gamma \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\) lies within the interval \(\left[\alpha \left(\mathcal{z}\right),\beta \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\right]\). Conversely, it is called an external cubic fuzzy set if for every \(\mathcal{z}\in {\mathbb{V}}\), \(\gamma \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\) falls outside the interval \(\left[\alpha \left(\mathcal{z}\right),\beta \left(\mathcal{z}\right)\right]\).

Definition 2 29

A cubic fuzzy graph (CuFG) on a non-empty set \({\mathbb{V}}\) is defined as a pair \(\psi =(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\), where \(\mathcal{A}\) is a cubic fuzzy set on of \(V\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) is a cubic fuzzy set of \({\mathbb{V}}\times {\mathbb{V}}\), For every edge \(\mathcal{w}\in {\mathcal{B}}^{*}\), the following conditions hold:

where \({\alpha }_{\mathcal{A}},{\beta }_{\mathcal{A}},{\gamma }_{\mathcal{A}}:{\mathbb{V}}\to [\text{0,1}]\) are the interval and fuzzy membership functions of the cubic fuzzy set \(\mathcal{A}\).

Definition 3 29

Let \(\psi =\left(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B}\right)\) be a cubic fuzzy graph (CuMG). The strength of an edge \(mn\in \mathcal{B}\), where \(m,n\in \mathcal{A}\) is defined as \({I}_{mn}=(\left[{I}_{mn}^{-},{I}_{mn}^{+}\right],{I}_{mn}^{*})\) with

An edge is called a strong cubic edge if \({I}_{mn}\ge \left(\left[\text{0.5,0.5}\right],0.5\right),\) Otherwise, it is considered a weak cubic edge.

In a CuMG, when two edges intersect, the intersection point is assigned a cubic valued number. Suppose edges \((\mathcal{r},\mathcal{s})\) and \((\mathcal{t},\mathcal{u})\) intersect; then, their strengths \({I}_{\mathcal{r}\mathcal{s}}\) and \({I}_{\mathcal{t}\mathcal{u}}\) are first computed. The cutting number at the intersection point \(P\) is defined as:

Clearly, \({I}_{P}\in \left[\text{0,1}\right]\).

Definition 4 32

Let \(\psi =(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\) be a cubic fuzzy graph (CuMG). For a particular geometric representation, let \({P}_{1},{P}_{2},\dots ,{P}_{k}(k\in {\mathbb{Z}})\) denote the cutting points formed by the edges of \(\psi\). Then, \(\psi\) is called a cubic planar graph (CuPG), and its degree of planarity is represented as \(F=\left(\left[{\mathfrak{f}}^{-},{\mathfrak{f}}^{+}\right],{\mathfrak{f}}^{*}\right),\) where

Here, \({I}_{{P}_{i}}^{-}\), \({I}_{{P}_{i}}^{+}\), \({I}_{{P}_{i}}^{*}\) denote the lower, upper, and exact components of the cubic valued number at the cutting point \({P}_{i}\), respectively.

Definition 5 33

Let \(\psi =(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\) be a strong cubic planar graph (CuPG) with degree of planarity \(F=(\left[\text{1,1}\right],1)\) on \(\mathcal{B}\). The region enclosed by the arrangement of edges \(E\) is called a face of \(\psi\). The strength of a face is defined as

A face with strength greater than or equal \((\left[\text{0.5,0.5}\right],0.5)\) is termed a cubic valued strong fuzzy face. Otherwise, it is called a cubic valued weak fuzzy face.

Definition 6 29

Let \(\psi =(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\) be a cubic planar graph (CuPG), i.e., a graph whose edges do not intersect. Suppose the faces of \(\psi\), enclosed by its edges, are denoted by \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1},{\mathfrak{f}}_{2},..,{\mathfrak{f}}_{k}\) where \(k\in {\mathbb{Z}}\).

The dual graph of \(\psi =(\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\), is defined as \({\psi }{\prime}=({\mathcal{A}}{\prime},{\mathcal{B}}{\prime})\), where \({\mathcal{A}}{\prime}\) is the vertex set and every vertex \({m}_{i}\in {\mathcal{A}}{\prime}\) corresponds to a face in \(\psi\). The cubic membership value of a vertex \({m}_{i}\) in the dual graph is given by:

\(\gamma \left({m}_{i}\right)=\{\left[\text{max}\left\{{\chi }^{-}\left(r,s\right)\right\},max \left\{{\chi }^{+}\left(r,s\right)\right\}\right],max \left\{{\chi }^{*}\left(r,s\right)\right|(r,s)\) are the edges bounding the face \(\}\}.\)

Definition 7 42

The order of a cubic fuzzy planar graph \((\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\), denoted as \({\mathbb{O}}(\psi )\) is defined by:

where:

-

(a)

\(RAL\left(r\right),RAU\left(r\right)\) denote the lower and upper values of the reference interval for vertex \(r\in R\),

-

(b)

\(\aleph AL\left( r \right)\), \(\aleph AU\left( r \right)\) represent the associated interval bounds of \(r\),

-

(c)

\({\mu }_{A}\left(r\right)\) is the fuzzy membership degree of vertex \(r\),

-

(d)

\({\lambda }_{A}(r)\) is an additional fuzzy value (often used for edge-strength or related property).

Definition 8 42

The size of a cubic fuzzy planar graph \((\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B})\) is denoted by \({\mathbb{S}}\left(\psi \right)\) and is defined as:

where:

-

(a)

\(RAL\left(rs\right),RAU\left(rs\right)\) denote the lower and upper values of the reference interval for vertex \((r,s)\),

-

(b)

\(\aleph AL\left( {rs} \right)\), \(\aleph AU\left( {rs} \right)\) represent the associated interval bounds of \((r,s)\),

-

(c)

\({\mu }_{A}\left(rs\right)\) is the fuzzy membership degree of vertex \((r,s)\),

-

(d)

\({\lambda }_{A}\left(rs\right)\) is the associated fuzzy value of \(\left(r,s\right).\)

Definition 9 19

Let \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) be a fuzzy planar graph (FPG) with planarity value of 1. The edge set is defined as

where \(\delta \left(x,y\right)\) represents the membership value of the pair \(\left(x,y\right).\) Suppose the fuzzy face of \(\psi\) are denoted by \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1},{\mathfrak{f}}_{2},{\mathfrak{f}}_{3},\dots ,{\mathfrak{f}}_{k}\) with \(k\in {\mathbb{Z}}\). The fuzzy dual graph of \(\psi\) written as \(\psi^{\prime } = \left( {\mathbb{V}^{\prime } ,\tau^{\prime } ,\delta^{\prime } } \right)\) is defined as follows:

-

(a)

The vertex set \({\mathbb{V}^{\prime}}\) consists of vertices \({x}_{i}\),each corresponding to a face \({\mathfrak{f}}_{i}\) of \(\psi\), for \(i=\text{1,2},\dots ,k.\)

-

(b)

If two faces \({\mathfrak{f}}_{i}\) and \({\mathfrak{f}}_{j}\) share a common boundary in \(\psi\), then the dual graph contains an edge \((x_{i} ,x_{j} ) \in E^{\prime}\).

-

(c)

The membership function \(\tau ^{\prime}:{\mathbb{V}^{\prime}} \to \left[ {0,1} \right]\) is defined by \(\tau^{\prime}\left( {x_{i} } \right) = \max \{ \delta \left( {r,s} \right)\left| {\left( {r,s} \right)} \right.\) are edges on the boundary of \({\mathfrak{f}}_{i}\)}.

When two fuzzy faces \({\mathfrak{f}}_{i}\) and \({\mathfrak{f}}_{j}\), share an edge \((a,b)\in E\), the membership value of the fuzzy edge \(\left( {x_{i} ,x_{j} } \right) \in \mathbb{V}^{\prime}\) is equals the membership value of the edge \(\left(a,b\right).\)

Definition 10 35

Let \(\psi\) be a fuzzy graph (FG) and let \({\mathbb{W}}\) be a subset of the vertex set \({\mathbb{V}}\) (i.e., \(\mathbb{W}\subseteq \mathbb{V}\)). The fuzzy subgraph obtained by deleting the vertices in \(\mathbb{W}\) from \(\psi\) is denoted by graph \(\psi\)\(-\mathbb{W}\), and is defined as:

This resulting fuzzy graph \(\psi\)\(-\mathbb{W}\) is called the vertex deletion fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\).

Definition 11 35

Let \(\psi\) be a fuzzy graph (FG) and let \({\mathbb{E}}\subseteq {\mathbb{U}}\) be a subset of its edge set. The fuzzy subgraph obtained by deleting the edges in \({\mathbb{U}}\) from \(\psi\) is denoted by \(\psi -{\mathbb{U}}\), and is defined as:

This resulting fuzzy graph \(\psi -{\mathbb{U}}\) is called the edge deletion fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\).

Definition 12 40

A fuzzy graph \(\psi\) is said to be a fuzzy outerplanar graph (FOGs) if it can be embedded in the plane in such a way that every vertex lies on the boundary of the outer (unbounded) region. Let \(i\left(\psi \right)\) denote the number of vertices in a planar embedding that do not lie on the boundary of the outer region. For a fuzzy outerplanar graph, we have \(i\left(\psi \right)=0.\)

Cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs

In this section, introduced the concept of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs, which extend the classical notion of outerplanarity to graphs with cubic fuzzy values. The focus is on defining the graph structure and understanding its properties in the context of cubic fuzziness.

Definition 13

A cubic fuzzy graph \(\psi\) is called a cubic fuzzy outerplanar graph (CuFOG) if it admits a planar embedding in which all vertices lie on the boundary of the outer face.

Let \(i\left(\psi \right)\) denote the number of vertices in the embedding that do not lie on the exterior boundary. Therefore, for a cubic fuzzy outerplanar graph (CuFOG), we have, \(i\left(\psi \right)=0\).

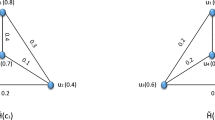

The graphs given in (Figs. 1, 2) are examples of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs.

Definition 14

A cubic fuzzy graph that cannot be embedded in the plane with all vertices positioned on the boundary of the exterior face is referred to as a cubic fuzzy non-outerplanar graph (CuFNOG).

In other words, it is a cubic fuzzy graph that does not satisfy the outerplanarity condition, since some vertices lie within the interior of the embedding rather than entirely on the outer boundary. If \(i(\psi )\ne 0\), then the cubic fuzzy planar graph is classified as a cubic fuzzy non-outerplanar graph (CuFNOG).

The graphs given in Figs. 3, 4 are examples of cubic fuzzy non outerplanar graphs.

Characterization of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs

In this section, we explore the defining theorems and example criteria that characterize cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs.

Theorem 1

A cubic fuzzy graph (CuFG) \(\psi\) is cubic fuzzy outerplanar graph (CuFOG) if and only if it does not contain any cubic subgraph that is homomorphic to \({\mathcal{K}}_{4}\) or \({\mathcal{K}}_{\text{2,3}}\).

Proof

It is well established that both \({\mathcal{K}}_{4}\) and \({\mathcal{K}}_{\text{2,3}}\) are not cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs (CuFOGs). Consequently, if a cubic fuzzy graph \(\psi\) contains a cubic fuzzy subgraph homomorphic to either \({\mathcal{K}}_{4}\) or \({\mathcal{K}}_{\text{2,3}}\), then \(\psi\) cannot be cubic fuzzy outerplanar. Hence, a cubic fuzzy graph is CuFOG precisely when it excludes such subgraphs, as illustrated in (Figs. 5, 6).

Conversely, let \(\psi\) be a CuFG that contains no cubic fuzzy subgraph homomorphic \({\mathcal{K}}_{4}\) or \({\mathcal{K}}_{\text{2,3}}\). By Kuratowski’s theorem, \(\psi\) is planar. Assume, for contradiction, that \(\psi\) is not CuFOG. Without loss of generality, we may take \(\psi\) to be a cyclic block that is not cubic fuzzy outerplanar. Furthermore, suppose \(\psi\) is embedded in the cubic fuzzy plane in such a way that the exterior region accommodates the maximum possible number of vertices.

Let the boundary of the exterior region be a cycle \(\mathcal{C}\). Since \(\psi\) is not CuFOG, not all vertices of \(\psi\) lie on \(\mathcal{C}\). Therefore, at least one vertex must lie in the interior of \(\mathcal{C}\).

If there exists a vertex \({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\) inside the cycle \(\mathcal{C}\) with three mutually disjoint paths connecting \({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\) to three distinct vertices of \(\mathcal{C}\), then \(\psi\) contains a cubic fuzzy subgraph that is homomorphic to \({\mathcal{K}}_{4}\).

Otherwise, since \(\psi\) forms a cyclic block, there must be a vertex \({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\) with two disjoint paths to two distinct vertices \({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\) and \({\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\) on \(\mathcal{C}\). From the choice of \(\mathcal{C}\), the edge \({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\) does not lie on the cycle. This implies that \(\psi\) contains a cubic fuzzy subgraph homomorphic to \({\mathcal{K}}_{\text{2,3}}\), which is a contradiction. Hence, the graph \(\psi\) in (Fig. 7) is a CuFOG. This concludes the proof.

Theorem 2

If \(\psi\) is a connected CuFOG, then it has a CuFDG \({\psi }^{*}\) there exist a vertex \(\mathfrak{v}\) such that \({\psi }^{*}-\mathfrak{v}\) contains no cubic fuzzy cycle.

Proof

Let \(\psi =(\mathbb{V},\tau ,\delta )\) be a connected CuFOG and there are no intersections of edges \(E^{\prime} \subset E\) within the graph, we can divide the CuFG into a finite number of regions. Each of these regions corresponds to a \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1},{\mathfrak{f}}_{2},{\mathfrak{f}}_{3},\dots {\mathfrak{f}}_{k}\) be the cubic fuzzy faces and membership value for each face is determined by,

\(\mathfrak{f}=(\left[{\mathfrak{f}}^{-},{\mathfrak{f}}^{+}\right],{\mathfrak{f}}^{*})=\left\{min\left\{\frac{\delta \left(\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\right)}{(\tau \left(\mathcal{x}\right)\wedge \tau \left(\mathcal{y}\right))}: \delta \left(\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\right)\in {E}{\prime}\right\}\right.\) Where \({E}{\prime}\) is the region bounded by the cubic fuzzy edges in cubic fuzzy planar graph.

When the CuFG divided into regions with cubic fuzzy face and values, it becomes very easy to CuFDG \({\psi }^{*}\) such that each face of \(\psi\) corresponds to a vertex and each edge of \(\psi\) corresponds to edge in \(\psi^{*} = \left( {\mathbb{V}^{\prime},\tau^{\prime},\delta^{\prime}} \right)\). Consequently, the cubic fuzzy dual graph \({\psi }^{*}\) exists for the cubic fuzzy outerplanar graph.

Since \(\psi\) is CuFOG. It is outer face is a cubic fuzzy cycle. Therefore, Fig. 8c the graph \({\psi }^{*}-\mathfrak{v}\) that results from removing the vertex \(\mathfrak{v}\) from \({\psi }^{*},\) the resulting graph \({\psi }^{*}-\mathfrak{v}\) contains no cubic fuzzy cycle.

Example 1

Consider the CuFOG \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) illustrated in the (Fig. 8a). If the dotted lines in (Fig. 8b) are superimposed CuFDG of \({\psi }^{*}\) and separated diagram. Here \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}\), \({\mathfrak{f}}_{2}\), \({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}\) and \({\mathfrak{f}}_{4}\) are four fuzzy faces. \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}),(\left[\text{0.3,0.2}\right],0.1\))), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.4,0.5}\right],0.25)\)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.3}\right],0.15\))); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{2}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.25,0.35}\right],0.45\))), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),([\text{0.5,0.3}]\),0.2)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),[\text{0.4,0.5}]\),0.3)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),([\text{0.5,0.3}]\),0.2)); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}),(\left[\text{0.25,0.35}\right],0.45)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.3}\right],0.2)\)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),([\text{0.4,0.3}]\),0.2)); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{4}\) is the outer face ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.4,0.5}\right],0.3)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.3}\right],0.15)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}),([\text{0.3,0.2}]\),0.1)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}),([\text{0.25,0.35}]\),0.45)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.4,0.3}\right],0.2)\)).The membership value of an cubic fuzzy faces \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}=\left(\left[\text{0.5,0.333}\right],0.166\right),{\mathfrak{f}}_{2}=\left(\left[\text{0.5,0.428}\right],0.333\right),\)\({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}=\left(\left[\text{0.416,0.428}\right],0.257\right),{\mathfrak{f}}_{4}=([\text{0.416,0.333}],0.166)\) are given in the (Table 2). Each cubic fuzzy face of \(\psi\) corresponds to a vertex and each edge of \(\psi\) corresponds to edge in \(\psi^{*} = \left( {\mathbb{V}^{\prime},\tau^{\prime},\delta^{\prime}} \right)\). Then \(\mathfrak{v}\) exists in such a way that \({\psi }^{*}-\mathfrak{v}\) contains no cubic fuzzy cycle.

Definition 15

If an edge cannot be added to a CuFOG \(\psi\) without sacrificing its outer planarity property, then the graph is cubic maximal fuzzy outerplanar graph.

The graphs given in Figs. 9, 10 are examples of cubic maximal fuzzy outerplanar graphs.

Definition 16

A CuFPG \(\psi\) is considered minimally cubic fuzzy non-outerplanar if \(i\left(\psi \right)\ne 0\) with atmost one vertex \(\mathfrak{v}\in \psi \text{ such that }\tau (\mathcal{x})>0\) in the interior region.

The graphs given in Figs. 11, 12 are examples of minimally cubic fuzzy non- outerplanar graphs.

Vertex deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs

In this section, the subgraph formed by removing specific vertices from the cubic fuzzy graph, while also defining cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs and offering relevant illustrations.

Definition 17

Assume \(\psi\) is a CuFPG. If \(\psi^{\prime}\) is the vertex deleted cubic fuzzy subgraph possessing outerplanarity property, then it is called VD-CuFOSs of \(\psi\).

Example 2

Let us consider the CuFG \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) shown in (Fig. 13a). The set of vertices in \(\psi\) is \({\mathbb{V}}=\left\{{\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right\}\) and their membership values of these are as follows: \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=\left([\text{0.7,0.6}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=\left([\text{0.75,0.9}],0.75\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=\left([\text{0.8,0.6}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=\left([\text{0.9,0.8}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.8,0.9}],0.8)\) and \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=\left([\text{0.8,0.6}],0.6\right),\) and the edges \({\mathbb{B}}\) is \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=([0.25\),0.1],0.25), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=([0.25\),0.3],0.3), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=([0.25\),0.4],0.2), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([0.3\),0.4],0.5), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([0.35\),0.4],0.3), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([0.5\),0.1],0.5), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{6},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([0.4\),0.2],0.4), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=([0.3\),0.2],0.1), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=([0.7\),0.8],0.2), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([0.3\),0.5],0.6), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([0.4\),0.5],0.2).

The edges intersect between the sets \(\tau ({ \mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6})\), and \(\tau ({ \mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5})\) within CFG \(\psi\) in (Fig. 13a). Let us define subsets \({\mathbb{X}}\) and \({\mathbb{Y}}\) in \({\mathbb{V}}\), where \({\mathbb{X}}=\) \(\left\{({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}(\left[\text{0.7,0.6}\right],0.7)\right\}\) and \({\mathbb{Y}}= \left\{{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}(\left[\text{0.9,0.8}\right],0.7)\right\}\) in the CFG \(\psi\).

The cubic fuzzy subgraphs \(\psi -{\mathbb{X}},\) represented as \({\psi }_{1}\) can be seen in (Fig. 13b). Similarly, the cubic fuzzy subgraph \(\psi -{\mathbb{Y}}\) represented as \({\psi }_{2}\) is shown in (Fig. 13c). It can be noted that, cubic fuzzy subgraph \({\psi }_{1}\) is categorized as a vertex deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph, while \({\psi }_{2}\) is classified as a VD-CuFOSs of\(\psi\).

Note 1

It is not necessary for the vertex deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph of \({\psi }_{ }\) to be the VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\). The cubic fuzzy graphs in (Fig. 13b,c) allow for the observation of this.

Theorem 3

A CuFOG \(\psi\) always has a VD-CuFOS that is also a vertex deleted cubic fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\).

Proof

Let the CuFOG be \(\psi\) and \({\mathbb{H}}\) be the vertex deleted cubic fuzzy subgraph of \({\psi }\). The vertices of the cubic fuzzy graph \(\psi\) will all be in the outer region since it is outerplanar. As a result, the cubic subgraph that was created by deleting vertices still has outerplanarity. Any vertex deleted cubic subgraph in \(\psi\) is therefore a VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Theorem 4

Let \(\psi\) be a CuFOG which is connected and let \({\mathbb{W}}\) be a subset of its vertices, such that \({\mathbb{W}}\subseteq {\mathbb{V}}\). The cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph of \(\psi\) with a vertex deleted is \(\psi{\prime} = \psi \backslash W\). Its CuFDG is \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\).

Proof

Let us consider a connected CuFOS \(\psi\) and \({\mathbb{W}}\subseteq {\mathbb{V}}\). let \(\psi -{\mathbb{W}}\) form a VD-CuFOS denoted \(\psi{\prime}\). Since there is no intersection of cubic fuzzy edges in the subgraph \(\psi{\prime}\), we can divide the CuFG into a finite number of regions. Each of these regions corresponds to a CuFF, and the membership values for each face is determined by.

\(\mathfrak{f}=(\left[{\mathfrak{f}}^{-},{\mathfrak{f}}^{+}\right],{\mathfrak{f}}^{*})=\left\{min\left\{\frac{\delta \left(\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\right)}{(\tau \left(\mathcal{x}\right)\wedge \tau \left(\mathcal{y}\right))}: \delta \left(\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\right)\in {E}{\prime}\right\}\right.\) Where \(E^{\prime}\) is the region bounded by the cubic fuzzy edges in CuFPG.

Using the fact that each CuFG with planarity value as 1 has cubic fuzzy dual graph, \(\psi -{\mathbb{W}}\) has a CuDG \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) Consequently, the CuDG exists for the VD-CuFOS of \(\psi .\)

Example 3

From Example, it is evident that the cubic subgraph \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) is the VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\) in (Fig. 14a). The dotted lines represent the superimposed CuFDG of \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) in (Fig. 14b). Here \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}\), \({\mathfrak{f}}_{2}\), \({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}\) and \({\mathfrak{f}}_{4}\) are four fuzzy faces. \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}),([\text{0.25,0.1}]\),0.25)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.25,0.3}\right],0.3)\)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),(\left[\text{0.25,0.4}\right],0.2)\)); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{2}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),([\text{0.25,0.3}]\),0.3)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}),(\left[\text{0.35,0.4}\right],0.6)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.1}\right],0.5)\)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.3,0.4}\right],0.5)\)); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}\) is bounded by the edges ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.1}\right],0.5)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{6},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.4,0.2}\right],0.4)\)); \({\mathfrak{f}}_{4}\) is the outer face ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}),([\text{0.25,0.4}]\),0.2)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}),([\text{0.25,0.1}]\),0.25)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}),(\left[\text{0.3,0.4}\right],0.5)\)), ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}),(\left[\text{0.5,0.1}\right],0.5)\)) and ((\({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}),(\left[\text{0.35,0.4}\right],0.3)\)). The CuFDG is associated with CuFF values, with all CuFFs having membership values of \({\mathfrak{f}}_{1}=(\left[\text{0.333,0.166}\right],\text{0,285}), {\mathfrak{f}}_{2}=(\left[\text{0.333,0}.166\right],0.428)\), \({\mathfrak{f}}_{3}=\left(\left[\text{0.5,0.166}\right],0.666\right)\) and \({\mathfrak{f}}_{4}=(\left[\text{0.357,0.166}\right],0.285)\) are shown in the (Table 3). Therefore, the Vertex Deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) indeed possesses a CuFDG.

Maximum and maximal vertex deletion cubic outerplanar subgraphs

This section defines the ideas of maximum and maximal vertex deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs and examines the relationship between these two conceptions with relevant examples.

Definition 18

If \(\psi^{\prime} = \left( {\mathbb{V}^{\prime},\tau^{\prime},\delta^{\prime}} \right)\) is the VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\) such that there is no other Vertex deleted cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph of \(\psi\) with maximum order and size compared to the cubic fuzzy subgraph \(\psi{\prime}\), then \(\psi{\prime}\) is said to be the maximum VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Note 2

Let order and size of the VD-CuFOS \(\psi{\prime}\) and \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) of \(\psi\) be \(\left( {\left[ {{\mathbb{O}}^{{ - \prime}} ,{\mathbb{O}}^{{ + \prime}} } \right],~{\mathbb{O}}^{{*\prime}} } \right)> \left( {[{\mathbb{O}}^{{ - \prime {\prime}}} ,{\mathbb{O}}^{{ + \prime {\prime}}} ],{\mathbb{O}}^{{*\prime {\prime}}} } \right)\) and \(\left( {\left[ {{\mathbb{S}}^{{ - \prime}} ,{\mathbb{S}}^{{ + \prime}} } \right],~{\mathbb{S}}^{{*\prime}} } \right)> \left( {[{\mathbb{S}}^{{ - \prime {\prime}}} ,{\mathbb{S}}^{{ + \prime {\prime}}} ],{\mathbb{S}}^{{*\prime {\prime}}} } \right)\) respectively. The cubic fuzzy subgraph \(\psi{\prime}\) is said to be maximum VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\) if \([{\mathbb{O}}^{{ - \prime }}\), \({{\mathbb{S}}^{-}}^{\prime}\)]\(>{{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{-}}^{\prime\prime}\), \({{\mathbb{S}}^{-}}^{\prime\prime}\)], \({{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{+}}^{\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{+}}^{\prime}\)]\(>{{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{+}}^{\prime\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{+}}^{\prime\prime}\)] and \({{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{*}}^{\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{*}}^{\prime}\)]\(>{{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{*}}^{\prime\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{*}}^{\prime\prime}\)] Suppose two VD-CuFOSs \({\psi }_{1}\) and \({\psi }_{2}\) are obtained in the CuFG \(\psi\). If \({\psi }_{1}{\ne \psi }_{2}\) but the order and size of two cubic fuzzy subgraphs are equal (i.e.),\({{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{-}}^{\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{-}}^{\prime}\)]\(={{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{-}}^{\prime\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{-}}^{\prime\prime}\)], \({{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{+}}^{\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{+}}^{\prime}\)]\(={{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{+}}^{\prime\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{+}}^{\prime\prime}\)] and \({{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{*}}^{\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{*}}^{\prime}\)]\(={{[{\mathbb{O}}}^{*}}^{\prime\prime}\),\({{\mathbb{S}}^{*}}^{\prime\prime}\)] then the two cubic fuzzy subgraphs are maximum VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Example 4

Let us consider the CuFG \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},{\mathbb{A}},{\mathbb{B}})\) shown in (Fig. 15). The set of vertices in \(\psi\) is \({\mathbb{V}}=\left\{{\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right\}\) and their membership values of these are as follows: \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=\left([\text{0.35,0.45}],0.55\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=\left([\text{0.45,0.55}],0.65\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=\left([\text{0.5,0.6}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=\left([\text{0.8,0.9}],0.9\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.25,0.35}],0.45)\) and \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=\left([\text{0.55,0.65}],0.75\right),\) and the edges \({\mathbb{B}}\) is \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([\text{0.1,0.2},]0.3\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([\text{0.3,0.2}],0.1\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([\text{0.2,0.3}],0.4\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([0.8\),0.9],0.9), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=([0.6\),0.7],0.8), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=([0.6\),0.7],0.8), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=([0.5\),0.6],0.7), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([0.8\),0.9],0.9), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=([\text{0.35,0.45}],0.55\)).

The VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\) are shown in (Fig. 16a–f). From the Table 4 note that Fig. 16c is the maximum VD-CuFOS of \(\psi .\)

Theorem 5

The CuFOS of maximum vertex deletion has a CuFDG, but the converse need not be true.

Proof

we can easily conclude that maximum VD-CuFOS has a CuDFG and that the converse need not be true based on the proof of Theorem 4.

Definition 19

The maximal VD-CuFOS of \({\psi }^{\prime}\) is \(\psi\) . This is because if a VD-CuFOS \({\psi }^{\prime}=({\mathbb{V}}^{\prime},{\tau }^{\prime},{\delta }^{\prime})\) induced on \(\psi\) and all other cubic fuzzy subgraphs of \(\psi\) induced by the vertex set \({\mathbb{V}}^{\prime\prime}={\mathbb{V}}^{\prime}\cup \left\{ \mathfrak{v}\right\}\) (where \(\mathfrak{v}\in {\mathbb{V}}\backslash {\mathbb{V}}^{\prime})\) does not satisfy the outerplanarity property.

Theorem 6

The CuFOS of each maximum vertex deletion is the maximal VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Proof

Let \({\psi }^{\prime}\) denote the maximum CuFOS of \(\psi\) resulting from vertex deletion. A subset \({\mathbb{W}}\ne {\varnothing }\subseteq {\mathbb{V}}\) exists, in which some of the \(\psi\) vertices have been deleted. Choose a vertex u in \({\mathbb{W}}\), and consider \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}={\psi }^{\prime}\cup \left\{\mathfrak{u}\right\}\) where \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}=\{\mathcal{x}\in {\mathbb{V}}^{\prime}\cup \frac{\left\{\mathfrak{u}\right\}}{\mu \left(\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\right)}\ne {\varnothing },\mathcal{x},\mathcal{y}\in {\mathbb{V}}\backslash {\mathbb{W}}\cup \left\{\mathfrak{u}\right\}\}\). Since \({\psi }^{\prime}\) is a maximum induced cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph, adding any of the vertex’s results u in \({f}_{\psi }\ne 1\). Hence, \({\psi }^{\prime}\) is the maximal induced vertex elimination cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph of \(\psi\). Therefore, every maximum induced VD-CuFOS is a maximal induced VD-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Theorem 7

The answer to Theorem 6 is not necessarily true.

Proof

Let \(\psi\) be the CuFG with \({\mathfrak{f}}_{\psi }\ne 1\) and, \({\psi }^{\prime}\) and \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}\) are the CuFOS of \(\psi\). Let \({\mathbb{W}}_{1}\),\({\mathbb{W}}_{2}\) be the subsets of vertex set \({\mathbb{V}}\) in \(\psi . {\mathbb{W}}_{1}\) and \({\mathbb{W}}_{2}\) contains the deleted vertices from \(\psi\) respectively. Then \({\psi }^{\prime}\) and \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}\) are said to be maximal VD-CuFOS if \({\psi }^{\prime}\cup \left\{\mathfrak{u}\right\}\) where \(\mathfrak{u}\in {\mathbb{W}}_{1}\) and \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}\cup \left\{\mathfrak{v}\right\}\) where \(\mathfrak{v}\in {\mathbb{W}}_{2}\) are CuFNOS.

With a maximal vertex deletion of \(\psi\), these cubic fuzzy subgraphs are therefore regarded as CuFOSs. Nevertheless, a VD-CuFOS can be described as a maximal VD-CuFOS with the largest order and size, since cubic fuzzy subgraphs can differ in size and order. Therefore, both cubic fuzzy graphs are maximal, but only one of them \(\psi{\prime}\) or \(\psi^{^{\prime\prime}}\) qualifies as a maximum VD-CuFOS. Therefore, any maximal vertex elimination does not necessarily have to have a cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph that is a maximum vertex deletion.

Note 3

Only when both cubic fuzzy subgraphs are maximum VD-CuFOSs as defined by Note 2 are two VD-CuFOSs maximal.

Example 5

Let us consider the CuFG \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) shown in (Fig. 17). The set of vertices in \(\psi\) is \({\mathbb{V}}=\left\{{\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right\}\) and their membership values of these are as follows: \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=\left([\text{0.45,0.8}],0.65\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=\left([\text{0.55,0.65}],0.75\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=\left([\text{0.6,0.7}],0.8\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=\left([\text{0.8,0.9}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.25,0.35}],0.45),\) and the edges \({\mathbb{B}}\) is \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=([\text{0.2,0.1}],0.4\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=([\text{0.3,0.5}],0.2\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=([\text{0.4,0.3}],0.2\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=([\text{0.3,0.2}],0.5\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.25,0.35}],0.45\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.8,0.8}],0.9\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.7,0.9}],0.9\)), \(\delta \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.18,0.19}],0.2\)).

All the graphs in Fig. 18a–e are maximal outerplanar of cubic fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\). But Fig. 18a is the maximum CuFOS of \(\psi\) in the (Table 5). Then it can be observed that maximal CuFOS need not be CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Edge deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs

The following subsections defined cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs, explained the subgraph produced by removing particular edges from the cubic fuzzy graph, and included pertinent examples.

Definition 20

If \(\psi\) is CuFPG and \(\psi{\prime}\) is its ED-edge deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph, then \(\psi{\prime}\) is ED-CuFOS of \(\psi\) if and only if it preserves a CuFPGs.

Note 4

There is no need for an ED-CuFOS of \(\psi\) to be an edge deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\).

Theorem 8

In a cubic fuzzy outerplanar graph \(\psi\), every edge deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph is always an ED-CuFOS of \(\psi\).

Proof

Let \(\psi\) be a CuFOS and let \({\mathbb{H}}\) be an edge deletion cubic fuzzy subgraph of \(\psi\). Since CuFG \(\psi\) is outerplanar, all its vertices will be in the outer region. Thus, the subgraph obtained by edge deletion still possess outerplanarity property. Therefore, any edge-deleted cubic fuzzy subgraphs in \(\psi\) are ED-CuFOSs of \(\psi\).

Theorem 9

Let \({\mathbb{W}}\) be the subset of edges of a connected CuFOG such that \({\mathbb{W}}\subseteq {\mathbb{E}}\). If \(\psi{\prime}\) is an ED-CuFOS of \(\psi\) if the resulting graph connects \(\psi{\prime}\) to the cubic fuzzy dual graph.

Proof

By using the same proof as Theorem 3 and which is obviously true for the case of edges.

Maximum and maximal edge deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs

The ideas of maximum and maximal edge deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs will be addressed in the following sections, along with an investigation into their relationship with appropriate examples.

Definition 21

Maximum ED- cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph (Maximum ED-CuFOS).

If \({\psi }^{\prime}=({\mathbb{V}}^{\prime},{\tau }^{\prime},{\delta }^{\prime})\) with size \(([{\mathbb{S}}^{-},{\mathbb{S}}^{+}],{\mathbb{S}}^{*})\) is the ED-CuFOS of non-outerplanar cubic fuzzy graph \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) such that there is no other Edge Deletion cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraph \({\psi }^{\prime\prime}\) of size \(([{\mathbb{S}}^{{-}^{\prime\prime}},{\mathbb{S}}^{{+}^{\prime\prime}}], {\mathbb{S}}^{{*}^{\prime\prime}})\) of \(\psi\) such that \(([{\mathbb{S}}^{{-}^{\prime\prime}},{\mathbb{S}}^{{+}^{\prime\prime}}], {\mathbb{S}}^{{*}^{\prime\prime}})>([{\mathbb{S}}^{{-}^{\prime}},{\mathbb{S}}^{{+}^{\prime}}], {\mathbb{S}}^{{*}^{\prime}})\), then \({\psi }^{\prime}\) is the maximum CuFOS of \(\psi .\)

Note 5

Suppose two ED-CuFOSs \({\psi }_{1}\) and \({\psi }_{2}\) is obtained from the CuFG \(\psi\). If the sizes of the two cubic fuzzy subgraphs are equal but \({\psi }_{1}{\ne \psi }_{2}\). (i.e.)\(([{\mathbb{S}}^{{-}^{\prime\prime}},{\mathbb{S}}^{{+}^{\prime\prime}}], {\mathbb{S}}^{{*}^{\prime\prime}})>([{\mathbb{S}}^{{-}^{\prime}},{\mathbb{S}}^{{+}^{\prime}}], {\mathbb{S}}^{{*}^{\prime}})\), then the two cubic fuzzy subgraphs are maximum ED-CuFOSs of \(\psi .\) This means that there is no unique maximum ED-CuFOSs of \(\psi\).

Example 6

Let us consider the CuFG \(\psi =({\mathbb{V}},\tau ,\delta )\) shown in (Fig. 19a) The set of vertices in \(\psi\) is \({\mathbb{V}}=\left\{{\mathfrak{v}}_{1},{\mathfrak{v}}_{2},{\mathfrak{v}}_{3},{\mathfrak{v}}_{4},{\mathfrak{v}}_{5},{\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right\}\) and their membership values of these are as follows: \(\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{1}\right)=\left([\text{0.5,0.6}],0.7\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{2}\right)=\left([\text{0.6,0.7}],0.8\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{3}\right)=\left([\text{0.2,0.3}],0.4\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{4}\right)=\left([\text{0.7,0.8}],0.9\right),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{5}\right)=([\text{0.15,0.25}],0.35),\uptau \left({\mathfrak{v}}_{6}\right)=([\text{0.1,0.2}],0.3)\) and the edges \({\mathbb{B}}\) is \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{1}\right)=([\text{0.25,0.34}],0.43\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{2}\right)=([\text{0.55,0.65}],075\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{3}\right)=([\text{0.8,0.9}],0.5\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{4}\right)=([0.2\),0.5],0.9), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{5}\right)=([0.7\),0.5],0.3), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{6}\right)=([0.1\),0.4],0.7), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{7}\right)=([0.5\),0.8],0.9), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{8}\right)=([0.6\),0.8],0.7), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{9}\right)=([\text{0.17,0.18}],0.19\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{10}\right)=([\text{0.95,0.25}],0.35\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{11}\right)=([\text{0.21,0.31}],0.41\)), \(\delta \left({\mathcal{e}}_{12}\right)=([\text{0.5,0.5}],0.5\))\(.\)

In Fig. 19b, the maximal ED-CuFOS are shown. Thus, a result, \(\psi -{\mathbb{U}}\) is the highest ED-CuFOSs of \(\psi\), and cubic fuzzy subgraph is maximal.

Application of cubic outerplanar graphs in face shape recognition

We consider that human face structure differs greatly from person to person in terms of face shape analysis. A face’s shape is a malleable, vague idea that is difficult to define exactly rather than a set entity. Therefore, fuzzy numbers are a logical way to model it. To account for the imprecision in facial traits like forehead breadth, cheekbone prominence, and jawline curvature, each person’s face shape is represented by a fuzzy number. However, intervals are used to depict this diversity when we think about a group of faces or the possible variation in face shapes within a population. The variety of potential facial shapes that could result from lifestyle, environmental, or hereditary factors can be observed in these intervals. When analyzing populations rather than individuals, the complexity of variability increases considerably. Facial characteristics are shaped by factors such as regional genetic diversity, nutrition, and age-related changes in skin flexibility and bone structure. To capture this broader diversity, interval-valued fuzzy numbers can be applied. Unlike a single fuzzy number for each person, intervals represent both the central tendency and the uncertainty around it, thereby outlining the possible range of facial structures. For instance, the average cheekbone prominence in one population may fall within an interval that overlaps with another, indicating indistinct yet shared boundaries.

An additional crucial factor in facial variability is the influence of environmental and lifestyle parameters on morphological development over time. Elements such as nutrition, physical activity, posture, and dental health can induce gradual modifications in facial components, including the jawline, cheeks, and forehead. For example, insufficient nutrition during growth phases may lead to reduced facial breadth, whereas orthodontic procedures can directly alter mandibular structure. Representing such variations through fuzzy numbers enables the modeling of continuous and progressive transformations, as opposed to abrupt reclassification into rigid facial categories. Genetic inheritance likewise plays a pivotal role in determining facial architecture. Although familial similarities are frequently observed, even siblings often exhibit distinct facial morphologies. This observation underscores that while genetics establish the structural framework, environmental and lifestyle influences refine and modulate the outcome. Consequently, interval-valued fuzzy modeling provides a robust and adaptable framework to encapsulate both genetic predispositions and the deviations introduced by external conditions.

From an application-oriented perspective, fuzzy modeling of facial morphology is relevant across several domains. In biometrics, exclusive dependence on crisp recognition algorithms may generate misclassifications when individuals exhibit overlapping or ambiguous facial attributes. The integration of fuzzy numbers enhances tolerance to imprecision and improves system robustness. In medical diagnostics, facial morphology is often employed as a clinical marker for genetic syndromes or developmental anomalies; fuzzy-based representations offer improved management of borderline instances where phenotypic traits only partially conform to standard diagnostic criteria. Similarly, cosmetic and reconstructive surgery benefits from fuzzy modeling, as surgical outcomes inherently involve uncertainty. By employing fuzzy numbers, the spectrum of possible postoperative results can be expressed more realistically, thereby supporting informed decision-making for patients. In anthropological and sociological investigations, fuzzy modeling facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of population-level variability, moving beyond rigid taxonomies that often oversimplify complex phenotypic diversity. For illustration, a representative facial image is provided in (Fig. 20).

Face image (This image is CC Licensed) https://share.google/images/DyuOQbYvgr6kdtLCa.

Additionally, factors including age, gender, ethnicity, and upcoming trends in cosmetic modifications can affect the variation. To account for soft boundaries, we may depict an individual’s current measurement of a particular facial characteristic (such as the breadth of the jaw) as a fuzzy number, whereas an interval represents the expected change over time or across a group of individuals. Not all faces have the same structural pattern; some can be rounder, a few more angular, while others are in between. This interval representation lets us account for this. Graph theoretic representation of vertex points from facial model given in the (Fig. 21).

Graph theoretic representation of vertex points from face image (Fig. 20).

Both subjective ambiguity and objective diversity in facial structures can be addressed by a resilient model that combines intervals for population wide variability and fuzzy numbers that represent individual faces. By concentrating entirely on the external contour and removing the interior nodes and connections that stand in for finer substructures, we streamline the underlying structure in the context of face shape analysis. Without highlighting the complexity of interior facial features, this abstraction highlights the face’s general boundaries while capturing its core shape. The outer vertices of our model, which depict the facial outline, match the main structural frame of the human face, including the curves of the cheeks, jawline, and forehead. The vertex membership values quantify how much variation is expected in the geometry of each individual face is given in the (Table 6).

Researchers are able to concentrate on the outward geometry by eliminating the inside vertices, which validates the notion that face form is an inaccurate and comprehensive concept that is ideal for fuzzy modeling. Interval representations are still used to capture the diversity within a population, even while individual face contours are modeled as fuzzy integers to express soft and ambiguous borders. A clearer yet more adaptable framework for evaluating and contrasting the shapes of human faces is made possible by this dual-level abstraction, which emphasizes main structural outlines over internal details. It is fuzzy at the individual level and interval-based at the group level.

To quantify the uncertainty in connections between facial feature points, fuzzy edge membership values are computed using a fuzzy edge calculation formula. Typically, the membership value \(\delta \left(\mathcal{e}\right)\) for an edge \(\mathcal{e}=(\mathfrak{u},\mathfrak{v})\) is defined based on the minimum of the vertex memberships shown in the (Table 7).

Or alternatively, through a similarity function or weighted distance between feature points, depending on the application. This allows the edge to reflect the vagueness in the spatial or relational positioning between facial landmarks.

To sum up, the utilization of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs offers a strong and user-friendly framework for simulating the ambiguity and variability present in face shape analysis, as illustrated in (Fig. 22). By limiting our attention to the graphs outside edge, which represents the main structural elements of the human face. Without being constrained by intricate internal linkages, we can express the basic geometry. Individual facial measurements are imprecise due to the graph’s fuzzy structure, whereas population-wide variability is accommodated using interval-valued representations. In addition to making computational modeling easier, this dual method closely resembles the inherent ambiguity and diversity seen in real-world facial features.

In summary, human face shape is not a fixed or sharply defined property but a flexible, imprecise characteristic influenced by multiple factors. Fuzzy numbers provide a natural framework for representing individual facial ambiguity, while interval-valued fuzzy models extend this representation to populations. This approach not only acknowledges the vagueness in defining facial shapes but also creates a practical tool for research, recognition systems, and applied sciences that rely on accurate yet flexible representations of human diversity. Therefore, in the fields of biometric, psychological, and aesthetic study, fuzzy outerplanar graphs are beneficial instruments for both representing and interpreting the contours of human faces. A useful method for modeling facial structures for face shape identification is to use cubic fuzzy graphs. They are helpful for increasing the precision and adaptability of biometric systems because of their capacity to manage ambiguity in the location and relationship of characteristics. Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Cubic Fuzzy Outerplanar Graphs in Face Shape Analysis is given in the (Table 8).

Conclusion

The article deals with the properties and characteristics of cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs. Several interesting aspects of their structures were observed, particularly that such graphs can be constructed from given cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs through the removal of specified vertices or edges. Both maximal and maximum cubic fuzzy outerplanar subgraphs obtained through vertex and edge deletions have been presented. Furthermore, the concept of cubic fuzzy dual graphs was introduced, along with a discussion on their derivation from cubic fuzzy outerplanar graphs and the interrelationships between them. This research opens the door for further studies regarding the theoretical importance and potential applications of these new graph structures. In particular, the study finds practical relevance in the domain of face shape recognition, where cubic fuzzy graphs provide an effective tool for representing the geometric structure of facial features. Their ability to handle imprecision in spatial relationships enhances the robustness and adaptability of biometric identification systems. As part of our future work, we plan to extend these investigations to fuzzy soft outerplanar graphs, exploring their theoretical properties, structural characterizations, and possible applications in image processing and pattern recognition.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zadeh, L. A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning—I. Inf. Sci 8 (3), 199–249 (1975).

Kaufmann, A. Introduction to the theory of fuzzy sets: Fundamental theoretical elements Vol. 1 (Academic Press, 1980).

Rosenfeld, A. Fuzzy graphs. In Fuzzy Sets and Their Applications to Cognitive and Decision Processes (ed. Rosenfeld, A.) (Academic Press, 1975).

Zadeh, L. A., Klir, G. J. & Yuan, B. Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic, and fuzzy Systems: Selected Papers (World Sci., 1996).

Abdul-Jabbar, N., Naoom, J. H. & Ouda, E. H. Fuzzy dual graph. J. Al-Nahrain Univ. 12 (4), 168–171 (2009).

Akram, M., Dar, J. M. & Farooq, A. Planar graphs under Pythagorean fuzzy environment. Mathematics 6 (12), 278 (2018).

Alshehri, N. & Akram, M. Intuitionistic fuzzy planar graphs. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 1, 397823 (2014).

Bhattacharya, P. Some remarks on fuzzy graphs. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 6 (5), 297–302 (1987).

Somasundaram, A. Domination in products of fuzzy graphs. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst, 13 (2), (2005).

Atanassov, K. T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 20 (1), 87–96 (1986).

Shannon, A., Atanassov, K.T. A first step to a theory of the intuitionistic fuzzy graphs. Proc. 1st Workshop Fuzzy Based Expert Syst, Sofia, 59–61, (1994).

Yager, R.R. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. Proc. Joint IFSA World Congr. and NAFIPS Annu. Meet, 57–61, (IEEE, Edmonton, 2013).

Pal, M., Samanta, S., Ghorai, G. Fuzzy tolerance graphs. Modern Trends Fuzzy Graph Theory. (Springer, 2020).

Akram, M., Sarwar, M. & Dudek, W. A. Graphs for the analysis of bipolar fuzzy information. Stud. Fuzziness Soft. Comput. 401, 452 (2021).

McAllister, M. L. N. Fuzzy intersection graphs. Comput. Math. Appl. 15 (10), 871–886 (1988).

Samanta, S. & Pal, M. Fuzzy planar graphs. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 23 (6), 1936–1942 (2015).

Nirmala, G. & Dhanabal, K. Special planar fuzzy graph configurations. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2 (7), 2250–3153 (2012).

Kuratowski, C. Sur le probleme des courbes gauches en topologie. Fund. Math. 15 (1), 271–283 (1930).

Samanta, S., Pal, M. & Pal, A. New concepts of fuzzy planar graph. Int. J. Adv. Res. Artif. Intell. 3 (1), 52–59 (2014).

Samanta, S., Pal, A. & Pal, M. Concept of fuzzy planar graphs. Sci. Infor. Conf. 7–9, 557–563 (2013).

Akram, M., Yousaf, M. M. & Dudek, W. A. Self centered interval-valued fuzzy graphs. Afr. Mat. 26, 887–898 (2015).

Akram, M., Alshehri, N. O. & Dudek, W. A. Certain types of interval-valued fuzzy graphs. J. Appl. Math. 1, 857070 (2013).

Pramanik, T., Samanta, S. & Pal, M. Interval-valued fuzzy planar graphs. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 7, 653–664 (2016).

Jun, Y. B., Kim, C. S. & Yang, K. Cubic sets. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform 4 (1), 83–98 (2012).

Muhiuddin, G., Ahn, S. S., Kim, C. S. & Jun, Y. B. Stable cubic sets. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. 23 (5), 802–819 (2017).

Rashid, S., Yaqoob, N., Akram, M. & Gulistan, M. Cubic graphs with application. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 16 (5), 733–750 (2018).

Yager, R. R. On the theory of bags. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 13 (1), 23–37 (1986).

Rashmanlou, H., Muhiuddin, G., Amanathulla, S. K., Mofidnakhaei, F. & Pal, M. A study on cubic graphs with novel application. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 40 (1), 89–101 (2021).

Muhiuddin, G., Hameed, S., Rasheed, A. & Ahmad, U. Cubic planar graph and its application to road network. Math. Probl. Eng. 1, 5251627 (2022).

Gulistan, M., Ali, M., Azhar, M., Rho, S. & Kadry, S. Novel neutrosophic cubic graphs structures with application in decision making problems. IEEE Access 7, 94757–94778 (2019).

Jan, N., Zedam, L., Mahmood, T. & Ullah, K. Cubic bipolar fuzzy graphs with applications. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 37 (2), 2289–2307 (2019).

Fang, G., Ahmad, U., Rasheed, A., Khan, A. & Shafi, J. Planarity in cubic intuitionistic graphs and their application to control air traffic on a runway. Front. Phys. 11, 1254647 (2023).

Ghorai, G. & Pal, M. A study on m-polar fuzzy planar graphs. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Math. 7 (3), 283–292 (2016).

Ghorai, G. & Pal, M. Faces and dual of m-polar fuzzy planar graphs. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 31 (3), 2043–2049 (2016).

Shriram, K., Sujatha, R. & Nagarajan, D. A fuzzy planar subgraph formation model for partitioning very large-scale integration networks. Decis. Anal. J. 9, 100339 (2023).

Krishna, K. K., Rashmanlou, H., Talebi, A. A. & Mofidnakhaei, F. Regularity of cubic graph with application. J. Indones. Math. Soc. 25 (1), 1–15 (2019).

Jiang, H., Talebi, A. A., Shao, Z., Sadati, S. H. & Rashmanlou, H. New concepts of vertex covering in cubic graphs with its applications. Mathematics 10 (3), 307 (2022).

Greenlaw, R. & Petreschi, R. Cubic graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 27 (4), 471–495 (1995).

Brinkmann, G., Goedgebeur, J., McKay, B.D. Generation of cubic graphs. Discrete Math. Theor. Comput. Sci, 13, (2011).

Deivanai, J., Sujatha, R., Nagarajan, D. & Tadesse, W. Fuzzy outerplanar graphs and its applications. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 17 (1), 231 (2024).

Deivanai, J., Sujatha, R., Nagarajan, D. & Tadesse, W. Bipolar fuzzy outerplanar graphs approach in image shrinking. Sci. Rep. 15, 24587 (2025).

Deivanai, J. & Sujatha, R. A Multipolar fuzzy outerplanar graph approach to one-way road network construction. J. Com. Anal. App. 34 (8), 463–500 (2025).

Deivanai, J., Sujatha, R., Nagarajan, D. & Tadesse, W. Network design for bypass roads using interval valued fuzzy outerplanar graphs. Sci. Rep. 15, 34018 (2025).

Muhiuddin, G., Hameed, S., Maryam, A. & Ahmad, U. Cubic Pythagorean fuzzy graphs. J. Math. 1, 1144666 (2022).

Xie, X. & Lam, K. M. Face recognition under varying illumination based on a 2D face shape model. Pattern Recog. 38 (2), 221–230 (2005).

Gökberk, B., İrfanoğlu, M. O. & Akarun, L. 3D shape-based face representation and feature extraction for face recognition. Image Vis. Comput. 24 (8), 857–869 (2006).