Abstract

The natural vibrational frequencies of biological particles encode critical information about their structures and properties. The natural vibrational frequencies have been explored for early detection and inactivation of viruses. The resonant frequency-based biophysical methods present an interesting alternative to traditional vaccine and drug treatment against the spread and infection of pathogenic viruses. However, measuring natural vibrational frequencies of a single virion in a biological environment is challenging. Assigning structural features to measured spectra is even more difficult. We have simulated the dynamic motion of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein using all-atom molecular dynamics simulation. A resonance frequency at 7.3–7.4 GHz has been identified. The finding provides a molecular-level theoretical basis for attributing the experimentally observed SARS-CoV-2 microwave absorption peak at ~ 7.5 GHz to the intrinsic vibration of the spike protein, which is different from the previously proposed viral shell-core dipole model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological particles such as proteins, viruses, bacteria and fungi display low-frequency vibrations. These vibrations arise from the collective motion of all their constituent atoms. The vibrational frequencies encode critical information about their size, shape, composition, three-dimensional structure and conformational flexibility, and interactions with their environments. The natural vibrational frequencies have been explored as fingerprints for viral detection and inactivation1,2,3.

The Influenza A virus H3N2 in solution was irradiated by microwave with the frequency range of 6–12 GHz. It has been shown that a 100% inactivation ratio can be achieved at a resonance frequency 8.4 GHz with power density \(\:810\hspace{0.33em}W/{m}^{2}\)4. Human coronaviruses (HCoV-229E) in solution were exposed over microwave irradiation in the range of 0.8–40 GHz. A resonance frequency within 15.0–19.5 GHz has been observed5. Small drops containing SARS-CoV-2 virus were exposed on microwave of frequencies ranging from 6.5 to 17 GHz. A resonance frequency at 10 GHz has been found6. These studies hypothesized that viruses could be physically ruptured by the resonant vibration of a confined dipolar mode inside a spherical virus. A dipole moment is formulated by the separation of viral shell and core with opposite electrostatic charges. The dipole mode could be resonantly excited by applied microwave with the same frequency as the vibration frequency of the dipolar mode, resulting in the rupture of the shell.

If the above hypothesis is true, the vibration frequency of the dipole mode can be inferred by the most effective viral inactivation frequency. However, the above observed resonance frequencies from empirically testing the inactivation effectiveness of a range of microwave frequencies are different from directly measured ones. Using a coplanar-waveguide-based sensor, two resonance frequencies have been directly measured at 4 and 7.5 GHz for SARS-CoV-2, and at 4.2 and 7.5 GHz for HCoV-229E, respectively7,8.

From the above brief review, it is clear that assigning structural features to measured spectra is challenging. The different resonance frequencies reported by different research groups for similar viruses call for the physical interpretation of resonance sources and underlying mechanism of inactivation.

The SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped virus with a spherical shape of diameter \(\:\sim\:100\hspace{0.17em}nm\) and mass \(\:m=\sim\:1\hspace{0.17em}fg\)9. The SARS-CoV-2 has four main structural proteins: nucleocapsid (N), spike (S), membrane (M), and envelope (E). The N protein surrounds the RNA genome, while the S, M, and E proteins are embedded in the lipid envelope. The S proteins protrude out of the spherical shell and look like crowns. The binding of the spike protein to the receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on human cells initiates the viral infection process. The vibration of any components may be resonated by exposed electromagnetic waves. Is there an alternative interpretation to the previously proposed “shell-core” dipole model to account for the experimentally observed ~ 7.5 GHz and ~ 4.0 GHz resonance?

Indeed, recent experimental studies of similar virus particles have suggested that at low frequency, viral inactivation is more likely due to the altering of S protein binding ability than the physical rupture of the particle10,11,12. Recent development of BioSonic spectroscopy has made it possible to detect natural vibrational frequencies from 2 to 21 GHz of a virus particle similar to SARS-CoV-2 virus. The low frequency from 2 to 10 GHz has been assigned to the vibration of virus envelope glycoproteins. The higher frequency from 19 to 21 GHz has been demonstrated to be sensitive to virus morphology13.

All-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have also shown that electric fields can dramatically denature the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S protein, resulting in complete loss of its binding affinity to ACE214,15. In our recent work, we have observed a permanent dipole moment nearly parallel to the axis of the S protein. Its interactions with applied electric fields denature the HR2 domain in the S2 unit to possibly break the membrane-fusion process16.

All-atom MD simulations have also been demonstrated to be a useful computational tool in interpreting optical absorption spectra from molecular structure and dynamics17,18,19,20. To theoretically account for the physical origin of the natural frequencies in the low frequency range from 2 to 10 GHz, we have carried out all-atom MD simulations of the S protein in the SARS-CoV-2 virus to determine if a resonance frequency could be identified.

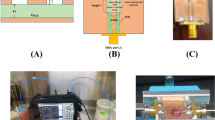

All-atom molecular dynamics simulations. (A) Set up of MD system. A spike protein of three chains in blue, red, and gray is embedded in a membrane (cyan). Three flexible hinges are marked in “hip”, “knee”, and “ankle”. The box size is 22.4 × 22.2 × 44.5 nm. For clarity, a portion of the water molecules is shown. (B) Evolution of radius of gyration of the spike protein in three independent simulations starting with different initial velocities.

Results

Energy absorption resonance frequency

The structure of the S protein has been revealed using cryo-electron tomography and MD simulation21,22,23. A 3-dimensional model of the S protein in a closed conformation embedded in a membrane is shown in Fig. 1A. The S protein is a trimer with each chain composed of the same 1273 amino acids. The three chains are in blue, red and gray in Fig. 1A. The S protein has a club-like shape with a head and a stalk. The head protrudes outside of the viral membrane, whereas the stalk connects the head to the viral membrane. The stalk has three flexible hinges: a hip, a knee, and an ankle. The knee between the upper leg and lower leg is most flexible. The feet insert into the viral membrane. The membrane model is composed of eight lipid types based on the ratio

.

estimated from influenza and HIV experimental data24. The system is solvated in 641,385 TIP3P water and neutralized with 0.15 M KCl solution. The total number of atoms in the system is 2,260,694. The simulation unit cell size is \(\:22.4\times\:22.2\times\:44.5\) nm. The initial configuration is available at https://www.charmm-gui.org/.

Assuming the S protein is exposed to an incident wave \(\:{E}_{0}\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\omega\:t\), \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:f\), and the energy absorption is isotropic. The quantum mechanical Golden Rule can be used to derive the amount of energy at a specific frequency absorbed per unit time as25

where \(\:\beta\:=1/{k}_{B}T\); \(\hslash\) is the reduced Planck’s constant; \(\:{i}^{2}=-1\); \(\:\overrightarrow{M}\left(t\right)=\left({M}_{x}\left(t\right),{M}_{y}\left(t\right),{M}_{z}\left(t\right)\right)\) is the total electric dipole moment of the S protein at time \(\:t\). The angular brackets denote the ensemble average of the dipole-dipole time correlation function at equilibrium. \(\:\mathcal{S}\left(\omega\:\right)\) is the power spectral density (PSD).

In the classical limit where \(\hslash \omega\:/{k}_{B}T\ll\:1\), Eq. (1) becomes

So \(\:{\left(dE/dt\right)}_{abs}\) is proportional to \(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\), the harmonic renormalization of the power spectral density:

\(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\) has the physical units \(\:Deby{e}^{2}\). The normalization factor \(\:\beta\:{\omega\:}^{2} \hslash\) is included to match the convention in the visual molecular dynamics (VMD) signal processing plugin package (version 1.1)26.

Within linear response theory where the perturbation is small from applied external field, \(\:\alpha\:\left(\omega\:\right)\equiv\:\frac{2\pi\:}{3nc \hslash }HS\left(\omega\:\right)\) is the absorption coefficient at frequency \(\:\omega\:\)25, where \(\:n\) is the refraction index, \(\:c\) is the speed of light in vacuum. The harmonic pre-factor \(\:{\left(\omega \hslash \right)}^{2}\) accounts for quantum correction.

To investigate whether there is an energy absorption resonance frequency, we need to compute the function \(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\) in the frequency range of interest. A frequency corresponding to a significant peak of the function \(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\) is called a resonance frequency, where more incident energy is absorbed than at other frequencies. In the following, we will refer to the plot of the function \(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\) as the absorption spectrum.

Resonance frequency predicted by MD simulation

We first calculate the PSD \(\:\mathcal{S}\left(\omega\:\right)\), \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:f\) and then multiply the prefactor \(\:\beta\:{\omega\:}^{2} \hslash\) to obtain \(\:HS\left(\omega\:\right)\). To numerically estimate \(\:\mathcal{S}\left(f\right)\), MD simulations have been employed to generate a discrete sample of dipole moments \(\:{\overrightarrow{M}}_{k}=\overrightarrow{M}\left(k\varDelta\:t\right)\) of the S protein, \(\:0\le\:k\le\:K-1\), where \(\:\varDelta\:t\) is the sampling period, and \(\:K\) is the total steps of a simulation. Following the Welch’s algorithm27, we have divided a time series into \(\:Q\) overlapping segments with equal segment data length \(\:L\) and 50% overlap. \(\:L\) is chosen to be even.

According to the Wiener-Khintchine theorem28,29, at each segment, \(\:\mathcal{S}\left(\omega\:\right)\) can be estimated as

where \(\:{f}_{j}=j\varDelta\:f\), \(\:0\le\:j\le\:L-1\), and \(\:\varDelta\:f=\frac{1}{L\varDelta\:t}\) is the frequency resolution, and \(\:{\widehat{F}}_{q}\left({f}_{j}\right)\) is the discrete Fourier transform of dipole moments:

Then the true \(\:\mathcal{S}\left({f}_{j}\right)\) is estiamted by the average:

Normalized microwave absorption spectra for three independent MD simulations. The strongest absorption intensity is scaled to 1. (A–C) Spectra calculated using a whole time-series vector. Maximum intensity appears at 7.4, 7.2, and 7.3 GHz for Sim0, Sim1, and Sim2, respectively. (D–F) Spectra calculated using equally divided segments of a time-series vector and then averaging the resultant spectra. Maximum intensity appears at 7.4, 7.3, and 7.3 GHz for Sim0, Sim1, and Sim2, respectively.

For each segment, we have calculated \(\:\beta \hslash {\left(2\pi\:{f}_{j}\right)}^{2}{\widehat{S}}_{q}\left({f}_{j}\right)\) using VMD1.9.4 signal processing plugin package specden26.

We have generated three time-series vectors of the total electric dipole moment of the S protein using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. By randomly re-initiating the velocity of atoms according to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at temperature 300.15 K, a previously equilibrated configuration has been restarted and simulated at the constant-temperature and constant-pressure (1 atm)16. The center of mass of the S protein is at the center of the simulation box. We have performed three independent simulations Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2 for 178.2 ns, 213.05 ns, and 202.5 ns, respectively. Trajectories were kept at the rate of \(\:\varDelta\:t=50\) ps for each of the three simulations, resulting in the Nyquist frequency 20 GHz.

The time evolution of the radius of gyration of the S protein is shown in Fig. 1B for the three simulations. The average radius of gyration of the S protein is 7.4686 \(\:\pm\:\) 0.0196, 7.4820 \(\:\pm\:\) 0.0306, and 7.5158 \(\:\pm\:\) 0.0296 nm for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2, respectively.

After wrapping the S protein back to the center of the simulation box using VMD PBCTools Plugin (version 2.7), the total electric dipole moments \(\:{\overrightarrow{M}}_{k}=\overrightarrow{M}\left(k\varDelta\:t\right)\) of the S protein for each simulation were calculated using VMD, where \(\:0\le\:k\le\:K-1\) and \(\:K=3564\), \(\:K=4261\), and \(\:K=4050\). The x, y, z components of the dipole moments are shown in Fig. 2A, B and C for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2, respectively. It is seen that there are more fluctuations in the z direction. This is because the stalk of the S protein is flexible to bend and stretch.

It has been demonstrated that the length \(\:L\) of the segments is a critical parameter for limited amount of data30. There is a balance between the length \(\:L\) and the number \(\:Q\) of the data segments. To obtain a high-resolution spectrum, the length \(\:L\) needs to be large, resulting in a small number of \(\:Q\) and large variance which may obscure the true signal. In contrast, if \(\:L\) is small and \(\:Q\) is large, a very smoothed spectra may smear out spectral structure. For small time series datasets with low signal-to-noise ratio, the choice of \(\:L\) becomes more critical.

We have first tested the case \(\:L=K\). In this case, \(\:Q=1\). A whole time-series is fed into the module specden in VMD signal processing package, the output harmonic renormalized spectral density functions are shown in Fig. 3A-C. The strongest absorption peaks appear at 7.4, 7.2 and 7.3 GHz for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2, respectively. However, the absorption spectra are very noisy in Sim0 and Sim1.

We have then tested varied \(\:L=512\), \(\:L=1024\), and \(\:L=2048\). Although we can observe that a peak around 7.5 GHz in all calculated spectra shown in Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information, a good balance between resolution and variance is achieved at \(\:L=2048\). The frequency resolution achieved at \(\:L=2048\) is 9.765625 MHz. The noise is significantly reduced. The normalized absorption spectra are shown in Fig. 3D–F. Now we can clearly see the strongest absorption peaks appear at 7.4, 7.3 and 7.3 GHz. The corresponding actual intensity is 0.01154, 0.01118 and 0.01571 \(\:Deby{e}^{2}\) for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2, respectively.

Significance test of the observed peaks

A problem in signal analysis is the false positive prediction of false peaks attributed to random noise31,32. We shall test whether the above observed maximum absorption intensity is due to a deterministic periodic component or random noise in the three data sets of time-series dipole moments. To this end, we have computed the false-alarm probability (FAP) using the bootstrap method33. The FAP measures the likelihood that the absorption peak of a similar magnitude can be observed after the time-series data are randomly resampled. If the FAP is high, the peak is most likely not due to a periodic structure of the data.

For each data set, we keep the temporal coordinates the same, but randomly draw dipole moment observations with replacement from the time-series, and then compute the maximum intensity of the corresponding spectrum using the same procedure. We repeat the process 10,000 times for each case. The distributions of the obtained maximum absorption intensities are plotted in Fig. 4A–C, where the FAP is defined as the probability that the obtained maximum absorption intensity is not less than the original maximum absorption intensity 0.01154, 0.01118 and 0.01571 \(\:Deby{e}^{2}\) for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2, respectively. It is seen that the FAP for Sim0, Sim1 and Sim2 is 8.61%, 4.34% and 0.05%, respectively. These FAPs imply that the likelihood for false positive prediction is very low. Further, the shapes of all the three distributions are the same with maximum intensity appears at \(\:0.007671\pm\:0.00044\) \(\:Deby{e}^{2}\), which is much smaller than our observed maximum intensity from the original data sets. Therefore, it is most likely that the observed peaks are due to a determined periodic component with frequency around 7.3–7.4 GHz.

Significance test of the observed peaks by calculating the false-alarm probability (FAP). (A) The maximum absorption intensity in Sim0 is 0.01154 \(\:{Debye}^{2}\). If it is due to noise, the probability of observing the maximum intensity is < 8.61%. (B) The maximum absorption intensity in Sim1 is 0.01118 \(\:{Debye}^{2}\). If it is due to noise, the probability of observing the maximum intensity is < 4.34%. (C) The maximum absorption intensity in Sim2 is 0.01571 \(\:{Debye}^{2}\). If it is due to noise, the probability of observing the maximum intensity is < 0.05%.

We note that the predicted FAP 0.05% in Sim2 is much smaller than Sim0 and Sim1, although the difference in the length of generated MD data points is small. To validate the variation of FAPs, we consider the following model modified from30:

where a cosine wave with frequency 7.5 GHz is completely overwhelmed by a Gaussian noise \(\:\mathcal{N}\left(0,20\right)\) with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 20.0.

Setting a random seed using numpy.random.seed (seed = 54321), the cosine wave with a frequency at 7.5 GHz is clearly revealed with FAP 0.11% using only 6,500 data points at the sample rate 1 point per 50 ps, as shown in Fig. S2. However, after resetting the random seed using numpy.random.seed (seed = 12345), the cosine wave is completely unobservable when only 6,500 data points are used, as shown in Fig. S3. When we use 11,000 data points, the cosine wave becomes observable with FAP 21.35%, as shown in Fig. S4. When we further increase the data points to 13,000, the cosine wave is clearly revealed with FAP 0.41%, as shown in Fig. S5.

This simple model demonstrates that FAPs depend on both the noise characteristics and the number of data points. For one noise distribution, 6500 data points are enough to achieve a high confidence with FAP = 0.11%. For the other noise distribution, 6500 data points are too small to reveal the cosine wave frequency 7.5 GHz. A data set of 13,000 has to be generated to reveal the 7.5 GHz cosine wave with FAP = 0.41%.

In our simulations, the random seeds to initialize velocities are different. The random seeds for Langevin dynamics to maintain a constant temperature and pressure during the simulations are different. Therefore, the underlying noise distributions are different. The above simple model well explains the variation of FAPs estimated from our simulations. The result 7.3 GHz in Sim2 has very high confidence with FAP = 0.05%, which is strongly supported by the other two replicates.

Localized domain vibrations

The S protein is made up of two subunits S1 and S2 which are cleaved at the site Arg685-Ser686 by cellular protease furin34. To investigate whether the 7.3–7.4 GHz peak is due to global conformational movements or localized domain vibrations of the S protein, we have recalculated the absorption spectra after separately selecting the S1 and S2 subunit of the S protein, respectively. The re-calculated absorption spectra are shown in Fig. S6 and S7, respectively. No significant peaks are observed in the S1 domain whereas profound peaks can be observed in the S2 domain at the same frequency 7.4 GHz, 7.3 GHz and 7.3 GHz for Sim0, Sim1, and Sim2, respectively. So, the S2 domain is the main contributor to the peak. This is in agreement with the observed flexibility of the S2 stalk domain from experiments23.

Discussion

Low-power non-thermal microwave technologies offer a novel strategy for viral detection and inactivation2,35,36,37,38. The natural resonance frequencies of virus particles are key parameters for the development of microwave-based devices1. Due to high sensitivity required to precisely detect and distinguish weak responses attributed to a small single particle and its components, it is technically challenging to experimentally measure the microwave absorption spectra of a single virion and to correctly assign structural features to the measured spectra.

Using a coplanar-waveguide-based sensor, two resonant frequencies of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified as 4 and 7.5 GHz7. The two frequencies have been assigned to two-body vibration of the viral shell and core. Recently, BioSonic spectroscopy has detected natural vibrational frequencies from 2 to 21 GHz of a virus particle similar to SARS-CoV-213. However, the low frequency from 2 to 10 GHz has been assigned to the vibration of virus envelope glycoproteins. To theoretically validate the frequency assignment, we have simulated the dynamic motion of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein using all-atom molecular dynamics simulation. Using the Welch’s algorithm in fast Fourier transform, we have identified a resonance frequency at 7.3–7.4 GHz. This provides an alternative explanation for the physical origin of experimentally measured microwave absorption resonance frequency of SARS-CoV-2 at 7.5 GHz. The observed dipole mode at 7.5 GHz is most likely attributed to the vibration of the spike protein rather than the displacement between the spherical shell and core. This agrees with the speculation from the BioSonic spectroscopy of a virus particle similar to SARS-CoV-2 virus that the low frequency from 2 to 10 GHz observed in the BioSonic spectroscopy is due to the vibration involved with virus envelope glycoproteins13.

This conclusion can be further validated by a recent experiment11. Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) as a surrogate of SARS-CoV-2 were illuminated by electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency (RF) range of 6–12 GHz. If the microwave at 7.5 GHz excited the resonant vibration of the shell and core resulting in physical rupture of the virus, nearly 100% inactivation of viral infectivity should be expected. However, up to 70% reduction in viral infectivity was observed in the experiments. So, the authors hypothesized the up to 70% reduction might be attributed to RF impact on S proteins.

Although our conclusion is strongly supported by those experiments, we have to point out that our conclusion is based on the study of a single S protein in its closed conformation. To achieve the goal of identifying resonant frequencies of viruses for microwave-based detection and inactivation of pathogenic viruses, we have to further solve the following problems.

-

(1)

Two absorption peaks have been experimentally observed. The peak at 7.5 GHz has been observed for both SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-229E. A peak at 4 GHz has also been identified for SARS-CoV-2. However, this peak shifts to 4.2 GHz for HCoV-229E in the same medium conditions. It has been proposed that the vibrational frequencies of a spherical particle can be estimated by numerically solving the Lamb’s Eqs39,40. For virus particles from 60 to 140 nm in diameter with longitudinal and transverse sound velocities of 1800 m/s and 900 m/s, the resonant frequencies have been estimated to be in the range of 7.4 to 17.2 GHz41. In our simulations, we are not able to observe any peaks around 4.0 GHz. What is the structural origin of the resonance peak around 4 GHz?

-

(2)

The S protein exhibits extensive conformational flexibility42. Molecular dynamics simulations have shown the vulnerability of the profusion conformation of the receptor-binding domain of the S protein in response to moderate electric field14. Here, we have simulated a closed conformation of the S protein. In an open conformation, an upright receptor-binding domain is flexible. How will the conformational change impact the absorption spectra?

-

(3)

Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that the S protein possesses a large dipole moment aligned with its axis16. The amplitude of the dipole moment is \(\:23313.34\pm\:30.22\) Debye. The intrinsic vibration of the dipole moment can be observed in Fig. 2 because of the flexibility of the three hinges: the hip, knee and ankle23. How the interactions between the RF and the dipole moment of the S protein impact its structure and function?

-

(4)

A SARS-CoV-2 virion particle has \(\:24\pm\:9\) spike proteins decorated on the surface43. Here, we have simulated a single S protein. How would the collective motion of all the S proteins impact the absorption spectra of a whole virion?

Computational methods

Molecular dynamics simulation

Starting with a previously equilibrated system16, three independent MD simulations were carried out under the condition of constant temperature (300.15 K) and constant pressure (1 atm) by randomly reinitializing the atomic velocities to a given temperature. All MD simulations were performed using the NAMD 3.0 package44. The CHARMM36 force field45 and TIP3P water model were used. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed in all 3-dimensions. Particle mesh Ewald summation46 was employed to account for long-range electrostatics. A 12 Å cutoff was implemented for short-range interactions. The bond lengths between a hydrogen atom and its attached heavy atom were constrained by the application of the SHAKE algorithm47.

Calculation of dipole moments

The electric dipole moments \(\:\overrightarrow{M}\) were calculated by:

where \(\:{q}_{j}\) and \(\:{\overrightarrow{r}}_{j}\) are the partial charge and vector position of the jth atom; \(\:N\) is the total number of atoms in selection; \(\:{\overrightarrow{R}}_{com}\) is the center of mass.

The dipole moments for a selected set of atoms were computed using VMD 1.9.4 command [measure dipole $sel -debye -masscenter] after wrapping the system back to the center of mass of the S protein. Since each trajectory frame requires about 178.6 MB memory to load, we used the following steps to overcome the large memory challenge. We first used [catdcd] plugin included in VMD to divide the whole trajectory into batches. Then we ran the Tcl script provided in the Supplementary Information from a terminal using the command [vmd -dispdev text -e diople.tcl].

Data processing

A discrete time series of dipole moments \(\:\overrightarrow{M}\left(k\right)=\overrightarrow{M}\left(kdt\right)\) were generated from a MD simulation using NAMD software, where \(\:0\le\:k\le\:K-1\), \(\:dt\) is the time step, and \(\:K\) is the total number of simulation steps. We divided the sequence into \(\:Q\) segments of length \(\:L\) with 50% overlap. Then the qth segment data \(\:0\le\:q\le\:Q-1\) is

For each segment, we calculated the harmonic renormalized spectral density using the fast Fourier transform which is implemented in the module specden in the VMD signal processing plugin package (Version 1.1). Then we took the average of the \(\:Q\) harmonic renormalized spectral densities as the final absorption spectrum.

Data availability

Data supporting this study are available at https://zenodo.org/records/16907381.

References

Contreras, G. S., López, F. E. J., Cesteros, G. S. & González, L. R. A. Biophysical methods for locating the resonance frequency of the virus. Key factor in the fight against covid-19. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 13, 233–245 (2020).

Sadraeian, M., Kabakova, I., Zhou, J. & Jin, D. Virus inactivation by matching the vibrational resonance. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, (2024).

Hartland, G. V. Acoustic resonances of biological nanoparticles. Adv. Photonics. 7, 030503–030503 (2025).

Yang, H. C. L. & Lin, S. C. Efficient structure resonance energy transfer from microwaves to confined acoustic vibrations in viruses. Sci. Rep. 5, 18030 (2016).

Banting, H., Goode, I., Flores, C. E. G., Colpitts, C. C. & Saavedra, C. E. Electromagnetic deactivation spectroscopy of human coronavirus 229E. Sci. Rep. 13, 8886 (2023).

Manna, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 inactivation in aerosol by means of radiated microwaves. Viruses 15, 1443 (2023).

Wang, P. J. et al. Microwave resonant absorption of SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–8 (2022).

Wang, P. J., Huang, T. W., Chen, Y. J. & Sun, C. K. Implementation of a coplanar-waveguide chip for the measurement of EM wave absorption spectrum of SARS-cov-2 virus. in Advances Terahertz Biomedical Imaging Spectroscopy 11975, 34–40 (SPIE, 2022).

Sender, R. et al. The total number and mass of SARS-CoV-2 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2024815118 (2021).

Afaghi, P., Lapolla, M. A. & Ghandi, K. Denaturation of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein under non-thermal microwave radiation. Sci. Rep. 11, 23373 (2021).

Cantu, J. C. et al. Evaluation of inactivation of bovine coronavirus by low-level radiofrequency irradiation. Sci. Rep. 13, 9800 (2023).

Pantoja, C. et al. Electromagnetic waves destabilize the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and reduce SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particle (SC2-VLP) infectivity. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–10 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nanoscopic acoustic vibrational dynamics of a single virus captured by ultrafast spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122, e2420428122 (2025).

Arbeitman, C. R., Rojas, P., Ojeda-May, P. & Garcia, M. E. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein is vulnerable to moderate electric fields. Nat. Commun. 12, 5407 (2021).

Lipskij, A., Arbeitman, C., Rojas, P., Ojeda-May, P. & Garcia, M. E. Dramatic differences between the structural susceptibility of the S1 pre-and S2 postfusion States of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein to external electric fields revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Viruses 15, 2405 (2023).

Kuang, Z. et al. Molecular dynamics simulations explore effects of electric field orientations on Spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 virions. Sci. Rep. 12, 12986 (2022).

Ding, T., Huber, T., Middelberg, A. P. & Falconer, R. J. Characterization of low-frequency modes in aqueous peptides using far-infrared spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. A. 115, 11559–11565 (2011).

Ding, T., Middelberg, A. P., Huber, T. & Falconer, R. J. Far-infrared spectroscopy analysis of linear and Cyclic peptides, and lysozyme. Vib. Spectrosc. 61, 144–150 (2012).

Zhang, M. et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of conformation and chain length dependent Terahertz spectra of Alanine polypeptides. Mol. Simul. 42, 398–404 (2016).

Ling, D., Zhang, M., Song, J. & Wei, D. Calculated Terahertz spectra of Glycine oligopeptide solutions confined in carbon nanotubes. Polymers 11, 385 (2019).

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV Spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020).

Walls, A. C. et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292 (2020).

Turoňová, B. et al. In situ structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike reveals flexibility mediated by three hinges. Science 370, 203–208 (2020).

Woo, H. et al. Developing a fully-glycosylated full-length SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein model in a viral membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B. 124, 7128–7137 (2020).

Zwanzig, R. Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD – Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Welch, P. The use of fast fourier transform for the Estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 15, 70–73 (1967).

Wiener, N. Generalized harmonic analysis. Acta Mathematica. 55, 117–258 (1930).

Khintchine, A. Korrelationstheorie der stationären Stochastischen prozesse. Math. Ann. 109, 604–615 (1934).

Solomon, O. M. Jr PSD computations using Welch’s method. NASA STI/Recon Technical Report N 92, 23584 (1991).

Mack, C. A. Systematic errors in the measurement of power spectral density. J. Micro/Nanolithography MEMS MOEMS. 12, 033016–033016 (2013).

Mack, C. A. More systematic errors in the measurement of power spectral density. J. Micro/Nanolithography MEMS MOEMS. 14, 033502–033502 (2015).

VanderPlas, J. T. Understanding the lomb–scargle periodogram. Astrophys. J. Supplement Ser. 236, 16 (2018).

Hoffmann, M., Kleine-Weber, H. & Pöhlmann, S. A multibasic cleavage site in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell. 78, 779–784 (2020).

Kubo, M. T. et al. Non-thermal effects of microwave and ohmic processing on microbial and enzyme inactivation: A critical review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 35, 36–48 (2020).

Calabrò, E. & Magazù, S. Viruses inactivation induced by electromagnetic radiation at resonance frequencies: possible application on SARS-CoV-2. World J. Environ. Biosci. 10, 1–4 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Zhao, L. & Peng, R. Effects of electromagnetic waves on pathogenic viruses and relevant mechanisms: A review. Virol. J. 19, 161 (2022).

Law, V. J. & Dowling, D. P. Microwave detection, disruption, and inactivation of microorganisms. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 13, 135–161 (2022).

Lamb, H. On the vibrations of an elastic sphere. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 1, 189–212 (1881).

Talati, M. & Jha, P. K. Acoustic phonon quantization and low-frequency Raman spectra of spherical viruses. Phys. Rev. E—Statistical Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 73, 011901 (2006).

Taylor, G. J. et al. on manna SARS-CoV-2 inactivation in aerosol by means of radiated microwaves. Viruses. 15, 1443. Viruses 15, 2110 (2023). (2023).

Wrobel, A. G. & Benton, X. P. SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Spike glycoprotein structures inform on virus evolution and furin-cleavage effects. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 763–767 (2020).

Ke, Z. et al. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 588, 498–502 (2020).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. The J. Chem. Physics 153, (2020).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 14, 71–73 (2017).

Darden, T. et al. Particle mesh Ewald: an n log (n) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10089 (1993).

Ryckaert, J. P., Ciccotti, G. & Berendsen, H. J. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 (1977).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Rajesh R. Naik for helpful discussion. We would like to thank Dr. Rajiv Berry for the DoD high performance computing resources. This work is funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZK, WPR, JL, RJT. Methodology: ZK. Investigation: ZK. Visualization: ZK. Evaluation: CH, BS. Funding acquisition and resources: NKL, ONR. Writing original draft: ZK. Review & editing: All.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official guidance or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense or of the United States Air Force.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuang, Z., Luginsland, J., Hung, CS. et al. Identifying resonant frequencies of viruses for microwave-based detection and inactivation of pathogenic viruses. Sci Rep 15, 43920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27669-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27669-4