Abstract

EUS-guided gastroenterostomy (EUS-GE) proved efficacy and safety for the management of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). Nevertheless, lack of standardization and lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) misdeployment are limiting its spread. The aim was to compare the wireless endoscopic simplified technique (WEST) and the direct technique over a guided-wire (DTOG) and to evaluate patency and maximal anastomotic tensile strength (MATS) after LAMS-in-LAMS salvage therapy. A prospective animal study was performed comparing DTOG and WEST techniques. After performing an EUS-GE, LAMS-in-LAMS was performed to treat involuntary or voluntary LAMS misdeployment. The animals were followed during 12 weeks. Primary endpoints included technical success, safety and easiness of the EUS-GE, while secondary endpoints included patency and MATS of the anastomosis. 11 EUS-GE were performed in 10 living pigs. The WEST had a high technical success (100% vs. 60%; p = 0.180), less voluntary misdeployment (33.3% vs. 100%, p = 0.060), a better easiness score (7/10 vs. 1/10; p < 0.01) and better technical outcomes (number of attempts and procedure duration) compared to DTOG. Concerning LAMS-in-LAMS, technical success was 81.8%. At week 10 LAMS were removed and at week 12, the anastomosis diameter was reduced by an average of 1.85 mm [range 0–9.5 mm]. The mean MATS was 27.46 ± 5.07 N. WEST resulted in higher technical success as compared to DTOG to create EUS-GE. In case of LAMS misdeployment, the LAMS-in-LAMS proofed to be a reliable rescue therapy with a good anastomotic patency and tensile strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

EUS-guided gastroenterostomy (EUS-GE) has become one of the treatment options of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). With a technical success rate of 90–95%1,2 and a high medium-term patency3,4, EUS-GE has supplanted duodenal stenting in the management of GOO patients unfit for surgery5,6. Moreover, compared with surgical gastroenterostomy (SGE), EUS-GE has shown equivalent technical and clinical success rates with fewer complications7,8,9,10. In addition, EUS-GE allows rapid restauration of oral intake. In expert hands, EUS-GE is now proposed as the first line treatment for the management of malignant or benign GOO in non-operable patients11.The main barriers to the widespread adoption of EUS-GE are the lack of standardization of the technique12 and the risk of misdeployment of the lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS)13,14. Despite the availability in the literature of a few tips and tricks to anticipate LAMS misdeployment15,16, the management of this complication requires a high level of endoscopic expertise and composture. Moreover, in case of failure of endoscopic salvage therapy, surgical management is proposed for patients often initially deemed unsuitable for surgery.

Since the first clinical case-report of EUS-GE in 201517, numerous variants of the EUS-GE technique have been described18. Distention of the target intestinal limb is no longer open to debate and is recommended prior to performing EUS-GE11,19. To increase the visibility of the target limb, an oro-intestinal drain20, a nasojejunal drain21 or a double balloon occluded catheter22 can be used. Concerning the creation of the anastomosis with the LAMS, recent data suggest that the wireless endoscopic simplified technique (WEST) is preferrable over the direct technique over a guidewire (DTOG)19,23. There are little data in the literature comparing these two EUS-GE techniques23,24 and standardization of the EUS-GE technique is still open to debate.

LAMS misdeployment is the most feared adverse events (AE) of the technique, with a risk reaching up to 10% in the literature25,26,27. Four types of LAMS misdeployment are described by the international EUS-GE study group25. Types I and II misdeployment are the most common. Type I misdeployment represents intraperitoneal deployment of the jejunal flange without enterotomy. In this case, endoscopic closure of the gastric orifice and redo-EUS-GE is advised25,28,29. Type II misdeployment also represents intraperitoneal deployment of the jejunal flange with enterotomy. In case of type II misdeployment, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES)30 or the stent-in-stent technique31,32 seem to be better options25. The use of NOTES may be appealing but requires a high level of endoscopic expertise. The stent-in-stent technique or LAMS-in-LAMS requires less expertise but there is few data on the outcome of the anastomosis saved by this technique33,34. In-depth characterisation of the mechanical properties of soft tissues is important to help predict how they will behave during and after the creation of an anastomosis35. The concept is being explored in digestive surgery to better understand the behaviour of digestive anastomoses and the risk of anastomotic strictures or leaks. The burst pressure of the anastomosis is one of the physical parameters to be tested36,37. It is used to assess resistance to intraluminal deformation. The tensile strength of the anastomosis is another measurable parameter, enabling the rupture point of the anastomosis to be assessed38,39.

The aim of this prospective animal study was to compare the outcomes of the DTOG and WEST technique in EUS-GE and to evaluate the endoscopic salvage therapy with LAMS-in-LAMS in case of misdeployment type II.

Methods

A 12-week prospective animal study was conducted between June 2022 and April 2023 at an academic animal research facility (Centre for surgery and transplantation research, CHEX, Catholic University of Louvain UCL, Brussels, Belgium). The study was approved by the university ethical committee (Ethics commission for animal experimentation Health sciences sector, Catholic University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium) for animal studies (ref: 2021/UCL/MD/072). All applicable institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed under approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). We declare that all methods, treatments and euthanasia followed the recommendations for animal care in accordance with the American Veterinary Medical association. All pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) were 3 months old females with normal health from the Rattlerow Seghers NV breeding company (Lokeren, Belgium). All pigs arrived at the university animal facility 7 days before the procedures. The study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines40.

EUS-GE anastomosis

Each animal underwent pre-procedural sedation by an intramuscular injection of hypnotic (Tiletamine/Zolazepam 6 mg/kg and Xylazine 2 mg/kg). It was then installed in the supine position on the operating table. A peripheral venous line was placed in an ear vein. Next endotracheal intubation was performed and gas anaesthesia was administered (Isofurane 3% for induction and 1.5% for maintenance). An injection of intravenous analgesic (buprenorphine 0.005–0.01 mg/kg) was given to ensure the animal’s comfort during the procedure and to manage post-procedural pain. All pigs received IV antibiotics (Cefazoline 2 g) prior to the procedure until three days after. This anaesthesia protocol has been accepted by the local ethics committee and follows the recommendations of practice for the anaesthesia of large animals in laboratory. All EUS-GE were performed by an experienced endoscopist under fluoroscopic control. First, an oro-intestinal drain (7Fr nasal biliary drain, Cook Medical, Dublin, Ireland) was inserted into the target intestinal limb using a colonoscope or a double channel gastroscope (CF-H180 or GIF-2TH180 Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to instil a mixture of saline with methylene blue and contrast medium. Then a therapeutic EUS endoscope (GF-UCT160, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the stomach to perform the EUS-GE procedure (supplementary materials: Fig. 1s). Each animal was randomised when entering the animal housing facility before the start of the study using an automated randomizer, and the operator discovered which type of technique was to be used on the day of the procedure. The two different EUS-GE techniques where thus performed in a random order throughout the study. Preemptive power calculation and sample size calculation were not performed because of the fear of unrealistically high numbers of animals required to complete the study based on the results obtained in retrospective clinical study23. Therefore, some results were to be interpreted with the risk of a statistically type II error.

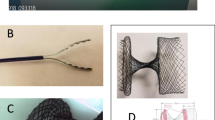

Regarding the WEST technique (supplementary materials: Fig. 2s), the EUS-GE was created using the freehand insertion of the electrocautery-enhanced LAMS (Hot Spaxus 16*20 mm, Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) using electrosurgical current (electrosurgical unit VIO 300 S, ERBE, Tübingen, Germany) in pure cut mode (effect 4, 120 W) between the gastric lumen and the target jejunal limb (Fig. 1a). The jejunal flange of the LAMS was deployed and a guidewire (Jagwire 0.035 inch, Boston Scientific, MA, USA) was advanced into the jejunal limb. The gastric flange was deployed under endoscopic and fluoroscopic view. Concerning the DTOG technique(supplementary materials: Fig. 2s), the dilated target intestinal limb was located and punctured (Fig. 1b) using a 19 G needle (19G EZ Shot 3, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan or a 19G Expect Slimline, Boston Scientific, MA, USA). A 0.035 inch guidewire was inserted through the needle into the jejunal lumen under fluoroscopic control. The puncture needle was removed and the electrocautery-enhanced LAMS catheter was advanced over the guidewire into the jejunal limb in pure cut mode (effect 4, 120 W). Finally, the LAMS was deployed between the jejunal and gastric lumen (Fig. 1c). The time of the procedure, the number of attempts, the need of salvage therapy and procedure-related AEs were registered.

Fluoroscopic images of both EUS-GE techniques (@: orointestinal catheter; ¤: electrocautery-enhanced catheter; &: EUS scope; # : 19 G needle; *: guidewire; + : lumen apposing metal stent). (a) Free hand puncture of the target jejunal limb of the wireless endoscopy simplified technique (WEST). (b) Needle puncture of the target jejunal limb of the direct technique over a guidewire (DTOG). (c) Deployment of the LAMS between the jejunal and the gastric lumen.

A questionnaire and a visual analogue scale assessing the ease of the procedure were completed by the endoscopist and the assistant at the end of the procedure. The easiness of the procedure was also assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS): the higher the score the easier the procedure.

In case of involuntary misdeployment type I, a second attempt was performed using the same technique. In case of involuntary misdeployment type II, a salvage therapy using the LAMS-in-LAMS technique was performed. The misdepolyed LAMS was dilated up to 15 mm using a dilatation balloon catheter (CRE-Wireguided balloon dilatation catheter, Boston Scientific, MA, USA). A second identical co-axial LAMS was placed over the guide wire through the misdeployed LAMS(Fig. 2a). The jejunal flange was deployed into the intestinal lumen and the jejunal limb was pulled backwards against the misdepolyed LAMS. Then, the co-axial LAMS was correctly deployed between the jejunal and gastric lumen through the misdepolyed LAMS (Fig. 2b and c). In case of initial success of EUS-GE, a voluntary misdeployment type II was created (Fig. 3a and b) by pulling the LAMS from the jejunal limb into the peritoneum using a rat tooth forceps (Rat tooth/alligator grasping forceps, Boston Scientific, MA USA) while maintaining the guidewire in place through the LAMS into the jejunal lumen. A salvage therapy using the LAMS-in-LAMS technique was then applied over the guidewire.

Endoscopic images of the creation of a voluntary misdeployment type II. (a) The jejunal flange of the LAMS was caught with a rat tooth forceps. The blue orointestinal catheter was visible inside the jejunal lumen. The guidewire was kept in place during the partial extraction of the LAMS. (b) The jejunal flange was pulled out into the peritoneum showing the mesenterial fat tissue.

After the procedure

All animals received IV antibiotics (Cefazoline 2 g) for three days. A pain scale for large animal was used to assess animal welfare41. A pain killer was administrated in function of the result of the pain scale results. After the procedure, the pigs had unlimited access to water. Feeding was resumed 24 h after the procedure if there were no clinical signs of suffering.

Follow up

The pigs were on a conventional cereal meal diet twice daily. Oral intake, animal wellbeing and behaviour were monitored daily per animal facility standard procedures and listed in a diary. The animals’ weight was recorded once a week. A follow-up upper endoscopy was performed once a week under sedation (Tiletamine/Zolazepam 6 mg/kg and Xylazine 2 mg/kg) to inspect the patency of the LAMS. Endoscopic removal of all LAMS was performed at week 10. Removed LAMS were examined for tissue interposition.

Euthanasia and final examination

At week 12, a final upper endoscopy was performed to inspect the patency of the gastroenterostomy without LAMS. Next the animals were euthanized (Tiletamine/Zolazepam 6 mg/kg and Xylazine 2 mg/kg associated with injection of T-61) and at necropsy, gross examination of the peritoneal cavity was performed to search for signs of inflammation, infection or abscesses. Each anastomosis was surgically resected and examined macroscopically. The diameter of each anastomosis was recorded using a ring size measure rod. Then the resected anastomosis segment was individually mounted to measure the anastomotic tensile strength and breaking point (supplementary materials: Fig. 4s). The tensile strength measurements were all performed immediately after the necropsy with surgical removal of the gastrojejunostomy and a jejunal segment under the environmental conditions of the research laboratory, i.e. a temperature of 20 ± 3 °C and humidity between 60 and 70%. An electronic scale with conversion to Newton was used for measurement related to weight and force. This scale was calibrated before use of each sample The suspension height (1.6 m) of the samples was always the same during all measurements and progressive stepwise increase of traction followed a strict protocol. The maximal anastomotic tensile strength (MATS) corresponded to the complete rupture of the anastomosis. The progressive lengthening of the anastomosis by the applied traction force was also measured. Similarly, tensile strength and breaking point of a normal jejunal segment was studied in parallel.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoints of the prospective animal study were the comparison of the technical outcomes and easiness of the WEST and DTOG EUS-GE techniques. Secondary endpoints were technical success of salvage therapy using the LAMS-in-LAMS technique, patency of the anastomosis and anastomotic tensile strength analysis.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using χ² or Fisher-exact tests. Normal and non-normally distributed variables were presented as mean (SD) and median (range). They were analysed using the Student t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis test accordingly. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. An internal validation of the VAS of the easiness of the procedure was assessed using Efron’s enhanced bootstrap method42. This method was applied to confirm the agreement between the qualitative response of the questionnaire and the score on the VAS of the easiness of the procedure. Statistical analyses were carried out using TIBO Statistica v13.3 software (University of Montpellier, research laboratory MRE-TRIS France).

Results

A total of 10 pigs were divided in two groups : 5 pigs randomly underwent the DTOG and 5 pigs the WEST technique.

Comparison of the outcomes of WEST and DTOG technique

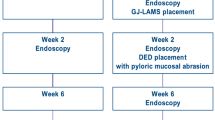

11 EUS-GE were performed with 5 in the DTOG group and 6 in the WEST group. A flow chart (Fig. 4) resumes the follow-up of the experiment. The mean time required to insert the oro-intestinal drain was 18.5 min ± 3.6 min and the mean number of attempts was 1.4. The mean distention diameter of the target jejunal limb at the start of the EUS-GE procedure was 21.2 mm in the WEST group and 20.8 mm in the DTOG group without significant difference (p = 0.84). Technical success to create the EUS-GE was higher in the WEST group than the DTOG group, which turned out to be more difficult to perform (100% vs. 60% respectively, p = 0.18). The rate of involuntary misdeployment was lower in the WEST group than in the DTOG group (33.3% vs. 100% respectively, p = 0.06). In the DTOG group, two pigs needed to be euthanized at the end of the procedure due to failure of endoscopic salvage therapy after spontaneous misdeployment. The mean procedure time was significantly lower in the WEST group than in the DTOG group (17 ± 8 min vs. 69 ± 18 min respectively, p = 0.002). The number of attempts was significantly lower in the WEST group than in the DTOG group (1.3 vs. 6.7 respectively, p = 0.003). Results are listed in Table 1. Apart from voluntary misdeployment, there were no other AEs reported during the creation of EUS-GE, such as bleeding.

The mean VAS score for technical easiness (Table 1) was significantly higher in the WEST group than the DTOG group (7/10 vs. 1/10 respectively, p < 0.001). The Efron’s enhanced boostrap method confirmed the agreement between the qualitative responses of the questionnaire and the quantitative score of the VAS (supplementary material: Fig. 5s).

Endoscopic rescue therapy with LAMS-in-LAMS

A total of 9 LAMS-in-LAMS were performed in 8 living pigs. Technical success of the LAMS-in-LAMS was 81.8%. Failure occurred in 2 pigs who needed to be euthanized at the end of the procedure because of untreated gastrointestinal perforation. A spontaneous distal migration of the two co-axial LAMS without clinical consequence was reported in one pig one week after the initial procedure (11.1%).

Patency of the anastomosis after LAMS-in-LAMS

Follow-up upper endoscopy was performed every week during 10 weeks in the 8 remaining pigs, confirming the correct position and patency of the LAMS. No occlusion of the LAMS due to food impaction or tissue overgrowth was observed. There were no other AEs during the follow up period such as perforation or bleeding or ulcer. All the LAMS (with a diameter of 16 mm) were endoscopically removed at week 10 using a rat tooth forceps. In all pigs, the co-axial LAMS were impacted in each other without tissue interposition (supplementary materials: Fig. 6 s). Endoscopic control prior to the necropsy at week 12 confirmed patency of the gastroenterostomy in all pigs (8/8). Moreover the gastroenterostomy was accessible with the endoscope in 7/8 pigs (87.5%). During the necropsy, signs of peritoneal inflammation with micro-abscesses were found in one pig (1/8, 12.5%). After the necropsy, the mean diameter of the anastomosis was measured at 13.3 ± 2 mm with a mean reduction of the diameter of 1.85 mm [0; 9.5]. Histological examination of one anastomosis confirmed fibrotic fusion of the gastric and jejunal tissues with formation of scar tissue (supplementary material: Fig. 7s).

Anastomotic physical resistance analyse

Physical resistance of the anastomosis was studied in 7 pigs. Among them, one anastomosis was used to test compatibility with a tensile strength testing machine without success because of size mismatch. Therefore, the point of rupture force was analysed in 6 anastomoses and tissue elasticity was analysed in 5 by applying progressive gradual traction force. The mean MATS was 27.46 ± 5.07 N and the mean lengthening of the anastomosis was 7.76 ± 1.75 mm until rupture. During the tensile strength test, all the models ruptured at the level of the anastomosis. Physical resistance of the jejunal tissue was studied in 6 pigs. The mean maximal jejunal tensile strength was 13.48 ± 2.72 N. The mean lengthening of the jejunal tissue was 87.4 ± 38.8 mm until rupture. All these results were reported in Table 2.

Discussion

We conducted a longitudinal porcine study to compare the outcomes of the WEST and DTOG techniques to perform EUS-GE and to evaluate the outcomes of endoscopic rescue therapy using the LAMS-in-LAMS technique. A comparison of different classical outcomes was performed. Although not all results reached statistical significance because of a typical type II error due to the limited sample size in each study group, the clinical and technical differences of the two techniques were clear. Technical success was higher in the WEST group with a shorter procedure time needing less attempts as compared to the DTOG group. Moreover, the risk of involuntary LAMS misdeployment was lower in the WEST group than in the DTOG group, illustrating that the DTOG technique using a guidewire turns out to be more difficult than the free-hand WEST technique. In the current study, the WEST technique was considered easier than the DTOG technique to perform EUS-GE as shown by the higher VAS score. These results confirm the superiority of the WEST technique over the DTOG technique for the creation of EUS-GE, as recently shown in a clinical retrospective human study23.In addition, Magahis et al. previously showed that the majority (71.4%) of EUS experts performing EUS-GE prefer the WEST technique because of its better technical feasibility and outcome19. Therefore, the WEST technique should be advocated as the standardized method of choice to perform EUS-GE, as shown both in animal and clinical studies.

Since the risk of LAMS misdeployment is an important issue hampering the wide spread use of the EUS-GE technique, we also studied the effectiveness of a salvage techniques and to evaluate the patency and strength of the anastomosis after the LAMS-in-LAMS rescue technique. This stent-in-stent technique is suggested for the treatment of misdeployment type II25. However, with the stent-in-stent technique for type II misdeployment, the jejunal wall is captured between the jejunal flanges of the co-axial LAMS, possibly reducing the chance of a correct fibrotic fusion of the gastric and jejunal wall. There are currently no animal or human studies on the outcomes and patency of EUS-GE after rescue therapy using this technique. Our survival porcine study clearly demonstrated the feasibility, effectiveness and safety of the LAMS-in-LAMS technique as a rescue therapy in case of stent misdeployment type II with a technical success of 81.8%. The high technical rescue success rate was most likely related to the introduction of a guide wire to secure the tract before the voluntary misdeployment. The guide wire seems therefore mandatory in the event of misdeployment type II in order to maintain access through the jejunal orifice and is best inserted after the jejunal flange has been deployed using the WEST technique. Earlier insertion of the guidewire may increase the risk of pushing away the target limb, as seen in the DTOG technique. This explains the higher rate of involuntary LAMS misdeployment in the DTOG group compared to the WEST group (100% vs. 33%, p = 0.06). This idea was also reported by some experts questioned in the study of Magahis et al.19. Although the LAMS-in-LAMS technique has been successful in more than 80% of cases, it might be that this rescue technique is more difficult to perform in cases of involuntary misdeployment as compared to the voluntary misdeployment under controlled conditions. Involuntary misdeployment happened more frequently using the DTOG technique, most likely because the guidewire being introduced into the jejunum before the LAMS is placed, also pushes away the adjacent jejunal limb from the stomach. This increase in distance between the stomach and the target jejunal limb increases the risk of both types I and II misdeployment. However, the presence of a guidewire through both the gastric and jejunal puncture site is the key to a successful LAMS-in-LAMS rescue procedure, which is usually the case using the DTOG technique. In case of unvoluntary LAMS misdeployment in the current study, care was taken to maintain the jejunal guidewire in place during the manoeuvre of partial LAMS removal creating a type II misdeployment. Therefore, in case of doubt or difficult LAMS release, it is advocated to keep a guide wire ready to be introduced into the jejunal lumen once the jejunal flange is opened, before completion of the procedure. The guide wire can help to rescue the procedure in case of LAMS migration out of the jejunal lumen into the peritoneal cavity while applying traction onto the stent before the release of the gastric flange.

The situation of LAMS misdeployment is considered a severe adverse event with potential lethal outcome, especially in the types II and III. Any rescue strategy requires expertise and composure to act with the necessary speed and accuracy. The LAMS-in-LAMS technique is an effective and rapid rescue procedure avoiding urgent surgical intervention. In this context the LAMS-in-LAMS technique is probably the most cost-effective, although comparative studies (LAMS-in-LAMS vs. urgent surgical repair) are lacking. The most promising and currently available tools to reduce LASM misdeployment primarily encompass obtaining proficiency and mastery of the EUS-GE WEST technique in combination with the choice of the ideal LAMS with optimal specifications of length and diameter, apart from more experimental devices like endoscopic anchors to create a gastro-jejunopexy before the EUS-GE procedure43,44.

Pending the development of new tools, training and the learning curve are currently the two most important factors in limiting the risk of misdeployment. Concerning the learning curve, proficiency in performing EUS-GE is achieved after 25 cases, while mastery is achieved only after 40 EUS-GE procedures45. The high number of procedures required to achieve mastery highlights that EUS-GE requires a high level of expertise and that regular training appears to be necessary. Simulators and models are useful to increase endoscopists’ performance and agility to perform endoscopy or EUS46. However, the creation of an ex vivo model or simulation for training in EUS-GE appears to be difficult. Indeed, numerous parameters must be mastered in order to replicate ‘real life’ as closely as possible in simulating the EUS-GE procedure. The key will probably be the use of virtual reality combined with artificial intelligence to create an adaptive simulation, similar to those found in flight simulators.

When looking at the patency of the gastroenterostomy, it was excellent even after LAMS-in-LAMS rescue technique during 10 weeks in all pigs, indicating that the jejunal tissue interposition between the two co-axial stents does not seem to mortgage the technical and clinical success of the rescued EUS-GE. However, after the removal of the LAMS, a mean reduction in the anastomotic diameter of 1.85 mm was noted. This progressive reduction of the diameter was also reported in 2 out 3 animals in the porcine study by Gonzalez et al.47. The ideal LAMS dwelling time resulting in a permanent and functional EUS-GE anastomosis is currently unknown. However, in the EUS-directed trans-gastric ERCP (EDGE) procedure, a comparable technique to create a gastrogastrostomy or jejunogastrostomy in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the only factor identified for persistent fistula is a long mean LAMS dwelling time (> 40 days in situ)48. In our study, the LAMS was kept in place for 70 days. It appears that the LAMS dwelling time is not the only factor explaining the progressive reduction of the anastomotic diameter after removal of the LAMS. A recent review on EUS-directed trans-gastric ERCP (EDGE) in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients identified three risk factors for persistent fistula after LAMS removal: LAMS diameter of 20 mm, long mean LAMS dwelling time (50 to 127 days) and attempt of spontaneous closure after LAMS removal49. These three factors increase the risk of a persistent fistula after the EDGE procedure. However, in contrast to the EDGE procedure, a persistent gastrojejunal fistula is aimed for in the EUS-GE procedure, also after removal of the LAMS. In malignant gastric outlet obstruction with poor patient prognosis, the LAMS is left in place after the creation of a EUS-GE until the patient’s death. However, in benign situations of gastric outlet obstruction, a long term persistent gastrojejunal fistula is the goal, even after removal of the LAMS. Therefore, clinical studies are ongoing comparing the replacement of the LAMS with the removal of the LAMS in the context of benign gastric outlet obstruction50.

The reduction of the diameter is part of the healing processes of a non-surgical anastomosis, that is activated after the removal of the LAMS. A recent porcine animal study showed the gradually increased expression of TGF-β1 and Smad 3 which play an important role in the formation of a stable gastrointestinal anastomosis51. This proactive process can help during the healing phase of the anastomosis until complete cicatrization of the fistula with a suitable diameter. However, if the healing process is prolonged after the initial creation of the anastomosis, it may result in continued and progressive fibrosis leading to a stricture or even complete closure of the anastomosis. Future studies are needed to elucidate the healing process of the EUS-GE anastomosis. The prolonged presence of the LAMS may continuously stimulate the inflammatory healing process with high levels of TGF-β1 and Smad 3. After LAMS removal, their high expression may further reduce the diameter of the anastomosis. The ideal interplay of the presence and removal of the LAMS with the levels of these cytokines remains to be elucidated. The use of a drug-eluting LAMS with anti-scarring agents (antiTGF-β1 and anti-SMAD3) could be a way to reduce the prolonged scarring process, as with active stents in interventional cardiology. For example, active LAMS may replace the initial conventional classical LAMS one month after the EUS-GE procedure in an attempt to reduce the risk of anastomotic stricture formation after final LAMS removal. However, in view of the expansion of EUS-GE indications to treat benign gastric outlet obstruction, long term patency after removal of the LAMS is warranted. This information is of the utmost importance, and further studies should focus on this topic.

The current study also focussed on the LAMS-in-LAMS rescue technique with biomechanical analysis of tensile and breaking force of the anastomosis created with the risk of tissue interposition between the two co-axial stents. It is the first study to introduce the concept of anastomotic physical resistance in EUS-GE. The mean MATS was 27,46 ± 5.07 N before rupture of the anastomosis. The tensile strength appeared to be better at the level of the fibrotic anastomosis as compared to normal jejunal tissue. In the literature, the mean maximal tensile strength in surgical small bowel anastomosis was 13.5 ± 3.76 N38,39. Even though the anatomical location and healing process differ, the resistance of the EUS-GE anastomosis, even after rescue therapy, was therefore at least equivalent to that of a surgical intestinal anastomosis in terms of biomechanical properties, despite the jejunal wall interposition between the two co-axial stents. The results of our study are encouraging, showing that the EUS-GE anastomosis is of reliable biomechanical quality even after the LAMS-in-LAMS rescue technique. However, comparisons must be made with caution, as the results in the literature relate only to small intestinal anastomosis, whereas the results of our study relate to gastrointestinal anastomosis. In addition, the tensile strength measurements should be performed in a standardized uniform way.

Conclusion

The WEST technique appears to be simpler and safer than the DTOG technique to perform EUS-GE in this porcine animal model. However, in case of misdeployment type II, LAMS-in-LAMS technique over the guide wire was shown technically successful and resulted in a good patency of the anastomosis. The biomechanical results of MATS after rescue therapy even outclassed the MATS of surgical small bowel anastomosis in the literature. The current study added valuable information to the knowledge of the recently developed EUS-GE technique and how to overcome failures using the stent-in-stent rescue method. Further animal studies are needed to compare MATS of surgical and EUS-guided anastomoses.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Iqbal, U. et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopic Ultrasound. 9, 16–23 (2020).

McCarty, T. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for benign and malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int. Open. 07, E1474–E1482 (2019).

Tsuchiya, T. et al. Long-term outcomes of EUS-guided balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass for malignant gastric outlet obstruction (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 101, 195–199 (2025).

Jaruvongvanich, V. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction: A large comparative study with long-term follow-up. Endosc Int. Open. 11, E60 (2023).

Asghar, M., Forcione, D. & Puli, S. R. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy versus enteral stenting for gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Therapeutic Adv. Gastroenterol. 17, 17562848241248220 (2024).

Conti Bellocchi, M. C. et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided gastroenterostomy versus enteral stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A retrospective propensity Score-Matched study. Cancers (Basel). 16, 724 (2024).

Abbas, A. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy versus surgical gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Endoscopy 54, 671–679 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy versus surgical gastroenterostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int. open. 10, E448–E458 (2022).

Miller, C. et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy vs. surgical gastrojejunostomy and enteral stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a meta-analysis. Endosc Int. Open. 11, E660 (2023).

Bronswijk, M. et al. Laparoscopic versus EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for gastric outlet obstruction: an international multicenter propensity score-matched comparison (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 94, 526–536e2 (2021).

Van Wanrooij, R. L. J. et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European society of Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) technical review. Endoscopy 54, 310–332 (2022).

Park, K. H. et al. Safety of teaching endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy (EUS-GE) can be improved with standardization of the technique. Endosc Int. Open. 10, E1088 (2022).

Teoh, A. Y. B. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided anastomosis: is it ready for prime time? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 1288–1293 (2020).

Wang, J., Hu, J-L. & Sun, S-Y. Endoscopic ultrasound guided gastroenterostomy: technical details updates, clinical outcomes, and adverse events. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 15, 634 (2023).

Kuo, Y. T. & Wang, H. P. A tent-like sign during endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: an indication of a misdeployed stent in the peritoneum. Endoscopy 55, E934 (2023).

Pausawasdi, N. et al. Pitfalls in stent deployment during EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy using hot Axios™ (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound. 10, 393 (2021).

Tyberg, A. et al. EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy after failed enteral stenting. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81, 1011–1012 (2015).

Irani, S. et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: techniques from East to West. VideoGIE 5, 48–50 (2020).

Magahis, P. T. et al. Preferred techniques for endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: a survey of expert endosonographers. Endosc Int. Open. 11, E1035 (2023).

Nguyen, N. Q. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy using an oroenteric catheter-assisted technique: A retrospective analysis. Endoscopy 53, 1246–1249 (2021).

Rai, P. et al. Nasojejunal tube-assisted endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction is safe and effective. DEN Open. 3, e210 (2023).

Itoi, T. et al. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided double-balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass (EPASS) for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Gut 65, 193–195 (2016).

Monino, L. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy with lumen-apposing metal stents: A retrospective multicentric comparison of wireless and over-the-wire techniques. Endoscopy 55, 991–999 (2022).

Chen, Y. I. et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: a multicenter study comparing the direct and balloon-assisted techniques. Gastrointest. Endosc. 87, 1215–1221 (2018).

Ghandour, B. et al. Classification, outcomes, and management of misdeployed stents during EUS-guided gastroenterostomy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 95, 80–89 (2022).

Giri, S. et al. Adverse events with endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy for gastric outlet obstruction—A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 12, 879–890 (2024).

Fabbri, C. et al. Hybrid gastroenterostomy using a lumen-apposing metal stent: a case report focusing on misdeployment and systematic review of the current literature. World J. Emerg. Surg. 17, 6 (2022).

Fuentes-Valenzuela, E. et al. Temporary EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction caused by severe acute pancreatitis (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound. 12, 164 (2023).

Vanella, G. et al. Redo-endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy for the management of distal flange misdeployment: trust your Orojejunal catheter. Endoscopy 54, E752–E754 (2022).

Rizzo, G. E. M. et al. Complete intraperitoneal maldeployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent during EUS-guided gastroenteroanastomosis for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: rescue retrieval with peritoneoscopy through natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. VideoGIE 8, 310 (2023).

Pandey, S. et al. Dislodged lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) in EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy salvaged by LAMS-in-LAMS technique. Gastrointest. Endosc. 97, 799–800 (2023).

Sondhi, A. R. & Law, R. Intraperitoneal salvage of an EUS-guided gastroenterostomy using a nested lumen-apposing metal stent. VideoGIE 5, 415–417 (2020).

Monino, L. et al. Alternative endoscopic salvage therapies using lumen-apposing metal stents for stent misdeployment during endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric intervention. Endoscopy 56, E892–E893 (2024).

Vanella, G., Dell’Anna, G. & Arcidiacono, P. G. EUS-directed transenteric ERCP with giant intrahepatic stone lithotripsy after a LAMS-in-LAMS rescue in response to a misdeployment. VideoGIE 9, 150–153 (2024).

Sif Julie, F. et al. Dynamic viscoelastic properties of Porcine gastric tissue: effects of loading frequency, region and direction. J. Biomech. 143, 111302 (2022).

Giusto, G. et al. Comparison of two different barbed suture materials for end-to-end jejuno-jejunal anastomosis in pigs. Acta Vet. Scand. 61, 3 (2019).

Tomori, K. et al. Comparison of strength of anastomosis between four different techniques for colorectal surgery. Anticancer Res. 40, 1891–1896 (2020).

Nygaard, M. S. et al. Remote ischemic postconditioning has a detrimental effect and remote ischemic preconditioning seems to have no effect on small intestinal anastomotic strength. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 57, 768–774 (2022).

Zheng, M. Y. et al. Short cycles of remote ischemic preconditioning had no effect on tensile strength in small intestinal anastomoses: an experimental animal study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 28, 1777–1782 (2024).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410 (2020).

Stasiak, K. L. et al. Species-specific assessment of pain in laboratory animals. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 42, 13–20 (2003).

Henderson, A. R. The bootstrap: a technique for data-driven statistics. Using computer-intensive analyses to explore experimental data. Clin. Chim. Acta. 359, 1–26 (2005).

Gao, H. et al. Double anchor lock fixing method to prevent stent displacement in endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: a Porcine study. Surg. Endosc. 36, 4854–4861 (2022).

Wang, G. X., Zhang, K. & Sun, S. Y. Retrievable puncture anchor traction method for endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: A Porcine study. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 3603–3610 (2020).

Jovani, M. et al. Assessment of the learning curve for EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for a single operator. Gastrointest. Endosc. 93, 1088–1093 (2021).

Coluccio, C. et al. Simulators and training models for diagnostic and therapeutic Gastrointestinal endoscopy: European society of Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) technical and technology review. Endoscopy 57, 796–813 (2025).

Gonzalez, J. M. et al. First fully endoscopic metabolic procedure with NOTES gastrojejunostomy, controlled bypass length and duodenal exclusion: a 9-month Porcine study. Sci. Rep. 12, 21 (2022).

Ghandour, B. et al. Factors predictive of persistent fistulas in EUS-directed transgastric ERCP: a multicenter matched case-control study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 97, 260–267 (2023).

Esckilsen, S. et al. Systematic review of technical factors associated with persistent fistula after EUS-directed transgastric ERCP in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. Epub ahead of print 8 April 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2025.03.1331

Giri, S. et al. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Gastroenterostomy for Benign Gastric Outlet Obstruction. DEN open; 6. Epub ahead of print 1 April 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/DEO2.70170

Hu, J. et al. The formation process and mechanism of Gastrointestinal anastomosis after retrieval anchor-assisted endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: a preclinical study. Surg. Endosc. 37, 2043–2049 (2023).

Acknowledgements

1. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) grant 2021. 2. Prion Medical (Belgium) and Taewoong Medical (Korea) for the free provision of Hot Spaxus 16*20 mm LAMS. 3. ERBE (Belgium) for the free provision of the electrosurgical unit. 4. Olympus (Belgium) for the free provision of the EUS endoscope and ultrasound machine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TG Moreels, M. Barthet, JM Gonzalez and L Monino concepted the study and analyzed the results. PH Deprez, R. Evrard, E. Bonacorsi helped to develop the concept for the soft tissue study.TG MOREELS and L Monino performed therapeutic endoscopy.P BALDIN analyzed the histologic samples.L Monino wrote the first draft of the manuscript.TG MOREELS adapted the first draft of the manuscript.All authors provided critical revision and correction of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the university ethical committee for animal studies (2021/UCL/MD/072).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monino, L., Gonzalez, JM., Evrard, R. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy with lumen-apposing metal stent: an animal study comparison of wireless and over-the-wire techniques. Sci Rep 15, 43915 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27688-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27688-1