Abstract

Before the introduction of antifibrotic therapy, patients with familial pulmonary fibrosis (FPF) were reported to have a higher mortality risk than those with sporadic disease. Genetic predisposition plays an important role in the development of interstitial lung disease (ILD), including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The 2023 European Respiratory Society consensus statement defined FPF and recommended antifibrotic drugs for treatment; however, their efficacy in FPF remains unclear. We conducted a retrospective multicohort study of 280 patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy (exploratory cohort, n = 141; validation cohort, n = 139). FPF was defined as fibrotic ILD in at least two first- or second-degree relatives. We examined tolerability, causes of drug discontinuation, incidence of acute exacerbation (AE), and mortality. Among all patients, 45 (16.1%) had FPF–IPF. These patients were younger and included a lower proportion of men compared with sporadic IPF. No significant differences were observed between groups in drug tolerability, discontinuation causes, AE incidence, or mortality. Multivariate analyses adjusting for gender–age–physiology index confirmed that FPF was not associated with increased mortality. In conclusion, under antifibrotic therapy, FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF demonstrated comparable tolerability, risk of AE, and mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), characterized by progressive worsening of dyspnea and lung function impairment, is a chronic and fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause with a poor prognosis1. Although the etiology of IPF remains unknown, growing evidence suggest that genetic factors and variants, such as telomere-related genes, surfactant-related genes, MUC5B, and TOLLIP, contribute to the development of IPF2,3. The 2023 European Respiratory Society (ERS) consensus statement defined familial pulmonary fibrosis (FPF) as “any fibrotic ILD in at least two blood relative first-degree or second-degree family members”3.

Although genetic testing is not routinely available in clinical practice, early studies reported that familial forms of the disease accounted for 2–4%4,5. Later, a large cohort study that included 1262 patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) showed that patient-reported pulmonary fibrosis, which met the 2023 ERS consensus statement of FPF, accounted for 25.1% of patients with IPF and 12.4% of non-IPF ILD patients6. FPF and a sporadic disease exhibit similarities in terms of clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and histopathology3,6,7,8. However, patients with FPF were generally younger and their disease tended to progress fibrosing ILD with limited survival3,6,7,8, indicating that patients with FPF are clinically important and distinct entities within ILDs.

Over the past decade, antifibrotic drugs (i.e., pirfenidone and nintedanib) have been shown to alleviate the annual decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) in patients with IPF9,10,11,12. Furthermore, nintedanib was found to exhibit similar efficacy in patients with progressive fibrotic ILD other than IPF13. Antifibrotic therapy has been recommended for treatment of IPF and progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF)1 and also endorsed in 2023 ERS consensus statement of FPF3. Consequently, numerous prospective and retrospective studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in patients with IPF and PPF. Given the distinct genetic background and clinical features associated with FPF, further investigation is warranted. However, to date, no studies have specifically evaluated the clinical efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in patients with FPF. Therefore, this multicenter retrospective study aimed to compare the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy between patients with FPF and those with sporadic IPF, focusing on survival outcome, incidence of acute exacerbation (AE), and tolerability.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 280 patients with IPF (combined cohort) are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1. No data on genetic mutation status were available for any of the patients. Among the 280 patients with IPF, 45 (16.1%) had a family history of ILD that met the criteria for FPF. The proportions of patients with FPF in the cohort 1 and 2 were 19.9% and 12.2%, respectively. Patients with FPF–IPF were diagnosed and started on antifibrotic therapy at a younger age than those with sporadic IPF. Patients with FPF–IPF had a higher proportion of women than those with sporadic IPF (28.9% vs 15.3%). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of smoking history, body mass index (BMI), or pulmonary function test results. Furthermore, patients with FPF–IPF had a slightly lower median GAP score, but the difference was not significant. The detailed characteritics of patinets in cohort 1 and cohort 2 were also showed in Supplementary Table 1.

Incidence of antifibrotic therapy discontinuation

Tolerability to antifibrotic drugs is clinically important. Therefore, this study first determined whether the discontinuation rate of antifibrotic therapy differed between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF. A total of 102 patients (36.4%) discontinued antifibrotic therapy due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or disease progression. The most common ADRs were gastrointestinal disorders, including loss of appetite, nausea, and diarrhea, followed by high liver enzyme levels, resulted in no differences in causes of discontinuation between patients with FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF (Table 2). The causes of discontinuation in each cohort were also depicted in Supplementary Table 2.

No significant difference was observed in the discontinuation rate between patients with FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF in the combined cohort (Fig. 2A). Additionally, we conducted sensitive analyses by examing cohort 1 and cohort 2 separately. In the cohort 1, patients with FPF–IPF had a slightly higher discontinuation rate than those with sporadic IPF, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B). In the cohort 2, the discontinuation rate did not differ between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF (Fig. 2C).

Cumulative incidence of antifibrotic therapy discontinuation between patients with sporadic IPF and those with FPF–IPF. Kaplan–Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of antifibrotic therapy discontinuation (all causes) according to the presence or absence of familial pulmonary fibrosis (FPF). (A) combined cohort, (B) cohort 1, and (C) cohort 2. Any death was considered a competing risk for antifibrotic therapy discontinuation for all causes. The P-values were determined via Gray’s analyses. IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, FPF Familial pulmonary fibrosis

Incidence of AE

Accordingly, the present study next evaluated the incidence of AE between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF undergoing antifibrotic therapy. A total of 27 patients experienced AE before the treatment initiation and were thus excluded from the analyses. Ultimately, 253 patients were included. During the observation period, 10 patients with FPF–IPF and 49 with sporadic IPF in the combined cohort developed AE. The cumulative incidence of AE did not differ between patients with FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF (Fig. 3A). In the cohort 1, 6 patients with FPF–IPF and 34 with sporadic IPF developed AE, whereas 4 patients with FPF–IPF and 15 with sporadic IPF developed AE in cohort 2. As showen in Fig. 3B and C, there were no significant differences in incidence of AE between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF in either cohort.

Cumulative incidence of acute exacerbation between patients with sporadic IPF and those with FPF–IPF. Kaplan–Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of acute exacerbation according to the presence or absence of FPF. (A) combined cohort, (B) cohort 1, and (C) cohort 2. Any death was considered to be a competing risk for antifibrotic therapy discontinuation for all causes. The P-values were determined via Gray’s analyses. IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, FPF Familial pulmonary fibrosis

Mortality risk and cause of mortality

Next, this study evaluated the mortality risk and cause of mortality in patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF. During the observation period, 24 patients with FPF–IPF and 134 with sporadic IPF died. As presented in Table 3, approximately half of the deaths in both groups were caused by disease progression resulting in chronic respiratory failure, whereas the other half were caused by AE and infection. In addition, nine patients with sporadic IPF died from lung cancer. The causes of deaths in each cohort were also depicted in Supplementary Table 3.

As regards the associations of mortality risk in patients with FPF–IPF, the median survival times in the combined cohort were 53 and 38 months for patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF, respectively, showing no significant difference in the survival time between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF (P = 0.112, Fig. 4A). The sensitive analyses yielded consistent results: in the cohort 1, the median survival times were 57 and 41 months for patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF, respectively (P = 0.21, Fig. 4B). In the cohort 2, the median survival times were also similar between the groups (43 and 32 months, respectively, P = 0.482, Fig. 4C).

Kaplan–Meier curves of patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy according to the presence or absence of familial pulmonary fibrosis. Kaplan–Meier curves of patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy in the (A) combined cohort, (B) cohort 1, and (C) cohort 2. according to the presence or absence of FPF. The P-values were determined via the log-rank test. IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, FPF Familial pulmonary fibrosis.

Multivariate analyses adjusted for the GAP index

Finally, this study determined whether the discontinuation rate, incidence of AE, and mortality risk differed between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF in the combined cohort, after adjustment for the GAP index. Fine–Gray proportional-hazards regression was employed to assess the discontinuation rate and AE incidence, considering all-cause mortality as a competing event. In contrast, Cox proportional-hazards regression was employed to evaluate mortality risk. As shown in Table 4, the presence of FPF was not associated with an increased risk of treatment discontinuation, a higher incidence of AE, or an increased mortality risk among patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy. The results were consistent when cohort 1 and cohort 2 were analyzed separately (Supplementary Table 4A and B).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF, focusing on tolerability, AE incidence, and mortality risk. The study found that the most common causes of antifibrotic therapy discontinuation in both patient groups were gastrointestinal disorders after disease progression, resulting in similar tolerability of antifibrotic therapy between the two groups. The cumulative incidence of AE did not differ between the groups. Furthermore, although patients with FPF–IPF were younger than those with sporadic IPF, both groups had similar survival times after antifibrotic therapy and causes of mortality. Given, patients with FPF-IPF had worse prognosis than those with sporadic IPF prior to the development of antifibrotic therapy6, these findings collectively suggest that antifibrotic therapy had provided at least comparable benefits to both patient groups.

Owing to the involvement of genetic predisposition and factors in the pathogenesis of fibrotic ILDs, including IPF, an international and multidisciplinary expert task force defined FPF as any fibrotic ILD in at least two first- or second-degree relatives3. Compared with sporadic IPF, FPF–IPF was diagnosed at a younger age and affected a lower proportion of male sex in our cohort, consistent with the findings of previous studies6,14. In contrast, although a previous study reported a small number of patients with smoking history in patients with FPF-IPF, no differences in smoking history was observed between the groups in the present study. Among the 280 patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy, 45 (16.1%) reported having a family history of ILD, thereby meeting the criteria for FPF. Contrarily, Cutting et al.6 recently reported an FPF–IPF incidence of 25.1%, which was relatively higher than that in our study. In this study, a thorough family history was obtained, it has possibility for underestimating the frequency of FPF. The present study relied on patient-reported family history. However, it is possible that the patients were not aware of the likelihood of a familial basis at the initial evaluation. Indeed, a study reported that at least 10% of sporadic IPF cases were subsequently reclassified as familial during follow-up, as blood relatives were later diagnosed with an IIP etc.15.

The present study demonstrates that tolerability, incidence of AE, and antifibrotic therapy discontinuation did not differ between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF. Malnutrition, low BMI, low performance status, and advanced disease defined by the GAP index were risk factors for discontinuations of antifibrotic therapy16,17,18,19. In these points, BMI and disease severity, such as GAP index, %FVC, and % DLCO, were not different between the two patient groups. These similarities in characteristics may be associated with tolerability to antifibrotic therapy in both groups.

The present study also evaluated the incidence of AE, which is a life-threatening event and is one of the common causes of mortality in patients with IPF20. The identified risk factors for AE-IIP include low FVC, low DLCO, poor baseline oxygenation, radiological honeycombing, and/or increased level of blood lactate dehydrogenase, Krebs von den Lungen 6, or surfactant protein D21,22,23. The INPULSYS study reported that nintedanib was significantly associated with reduced incidence of AE12. Several clinical studies have also reported that antifibrotic therapy appears to reduce the risk of AE in patients with IPF24,25. In the present study, these risk factors, including pulmonary function test results and blood markers, were comparable between the patient groups. Collectively, our results indicated that antifibrotic therapy might help to reduce AE incidence in patients with FPF–IPF, similar to its effects in patients with sporadic IPF.

A large cohort study consisting of 534 patients with IPF and 728 patients with non-IPF reported that the risk of mortality or lung transplantation was significantly higher in patients with FPF–IPF than in those with sporadic IPF as well as in FPF-Non-IPF patients than in their sporadic counterparts6. In that study, the patient enrolment spanned 2003 to 2019, suggesting that majority of the patients were enrolled before the widespread use of antifibrotic therapy. Notably, this study reported no significant differences in survivals after the initiation of antifibrotic therapy between patients with FPF–IPF and those with sporadic IPF. As regards baseline characteristics, patients with FPF–IPF were significantly younger and had a lower proportion of male sex. These differences may influence the outcome of fibrotic ILDs, as age and sex are known to be prognostic factors included in the GAP and ILD-GAP indices26,27. Therefore, this study evaluated the mortality risk of patients with FPF–IPF, with adjustment for the GAP index, and found that the presence of FPF–IPF was not associated with increased mortality risk in antifibrotic therapy. As the presence of FPF–IPF was higher mortality risk before the advent of antifibrotic therapy, our findings suggest that antifibrotic therapy provides provided at least comparable benefits to both patient groups.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was a retrospective design and included a relatively small number of FPF–IPF cases. Second, identification of FPF–IPF was solely on patient-reported family history without standardized documentation, which might have led to underestimation and contributed to the lack of significant differences in mortality between FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF. Third, the present study consistent with Asian ethnicity, limiting the generalizability of the results. Fourth, this study included only patients with FPF–IPF, eventhough FPF can be diagnosed in other form of fibrotic ILDs. Therefore, it did not evaluate the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in patients with FPF associated with PPF (non-IPF). In addition, no data on genetic mutation status were collected. Therefore, a prospective study with standardized procedures, inclusion of diverse ethnic groups and patients with FPF–PPF, and genetic analyses are warranted to further validate our findings.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with FPF–IPF and sporadic IPF exhibited similarity in terms of tolerability to antifibrotic therapy and cumulative incidence of AE. Notably, the presence of FPF–IPF was not increased risk for mortality compared to sporadic disease. Collectively, our results suggest that antifibrotic therapy is equally safe and beneficial for patients with FPF–IPF.

Methods

Ethical approval of the study protocol

This multicenter retrospective study was performed in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of the study protocol was obtained from the institutional review boards of the participating centers: Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (24–153), Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital (4741), and Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital (24–153). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Owing to the retrospective design of the study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Patients

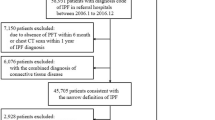

This retrospective study initially enrolled 306 consecutive patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) who received pirfenidone or nintedanib therapy at Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (cohort 1, n = 150) and at Seirei Mikatahara Hospital and Seirei Hamamatsu Hospital (cohort 2, n = 156). All patients commenced antifibrotic therapy between February 2009 and December 2024. The follow-up period extended from treatment initiation to the last clinical visit, with censoring applied to patients who remained alive as of May 31, 2025. After excluding 26 individuals whose family history of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) could not be determined, 280 patients were included in the final analysis (cohort 1, n = 141; cohort 2, n = 139, Supplementary Fig. 1). No data on genetic mutation status were collected for the patients.

The diagnosis of IPF was made according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Latin American Thoracic Association criteria1,28,29. Meanwhile, AE was diagnosed following the American Thoracic Society guidelines20. The 2023 ERS consensus statement defined FPF as any fibrotic ILD in at least two first- or second-degree relatives3.

Data collection

Clinical information was retrieved from the patients’ medical records. Laboratory data, together with pulmonary function test results at the initiation of antifibrotic therapy, were documented.

Assessment of the GAP index

The GAP index was calculated using baseline data at the time of antifibrotic therapy initiation, according to previously described26.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts with corresponding percentages, and continuous variables are summarized as medians with interquartile ranges. Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Overall survival was defined as the time from initiation of antifibrotic therapy to death, and survival curves were generated with the Kaplan–Meier method. Group differences in survival were assessed using the log-rank test. To identify prognostic factors for mortality, Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were conducted. Treatment discontinuation and incidence of AE were analyzed as a time-to-event outcome. The cumulative probability of discontinuation and AE were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier approach, while Gray’s test was applied to evaluate differences across groups in the presence of competing risks. Fine–Gray regression models were subsequently fitted to determine factors independently associated with discontinuation and incidence of AE, with death treated as a competing event. Variables entered into Cox and Fine–Gray models were selected based on clinical relevance. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Raghu, G. et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 205, e18–e47. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST (2022).

Borie, R. et al. The genetics of interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0053-2019 (2019).

Borie, R. et al. European respiratory society statement on familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01383-2022 (2023).

Hodgson, U., Laitinen, T. & Tukiainen, P. Nationwide prevalence of sporadic and familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence of founder effect among multiplex families in Finland. Thorax 57, 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.57.4.338 (2002).

Marshall, R. P., Puddicombe, A., Cookson, W. O. & Laurent, G. J. Adult familial cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in the United Kingdom. Thorax 55, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.55.2.143 (2000).

Cutting, C. C. et al. Family history of pulmonary fibrosis predicts worse survival in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest 159, 1913–1921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.026 (2021).

Lee, H. L. et al. Familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Clinical features and outcome. Chest 127, 2034–2041. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.6.2034 (2005).

Steele, M. P. et al. Clinical and pathologic features of familial interstitial pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 1146–1152. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200408-1104OC (2005).

Noble, P. W. et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): Two randomised trials. The Lancet 377, 1760–1769. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60405-4 (2011).

Richeldi, L. et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1103690 (2011).

King, T. E. Jr. et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2083–2092. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402582 (2014).

Richeldi, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2071–2082. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402584 (2014).

Flaherty, K. R. et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1718–1727. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1908681 (2019).

Duminy-Luppi, D. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of family history of fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Res. 25, 433. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-024-03063-y (2024).

Kropski, J. A. et al. Genetic evaluation and testing of patients and families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195, 1423–1428. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201609-1820PP (2017).

Oishi, K. et al. Medication persistence rates and predictive factors for discontinuation of antifibrotic agents in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A real-world observational study. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 13, 1753466619872890. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753466619872890 (2019).

Sugino, K., Ono, H., Saito, M., Ando, M. & Tsuboi, E. Tolerability and efficacy of switching anti-fibrotic treatment from nintedanib to pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE 19, e0305429. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305429 (2024).

Mochizuka, Y. et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is a predictor of tolerability of antifibrotic therapy and mortality risk in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 28, 775–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14523 (2023).

Romero Ortiz, A. D. et al. Antifibrotic treatment adherence, efficacy and outcomes for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain: A real-world evidence study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001687 (2024).

Collard, H. R. et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An international working group report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 194, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI (2016).

Song, J. W., Hong, S. B., Lim, C. M., Koh, Y. & Kim, D. S. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur. Respir. J. 37, 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00159709 (2011).

Collard, H. R. et al. Acute exacerbations in the INPULSIS trials of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01339-2016 (2017).

Karayama, M. et al. A predictive model for acute exacerbation of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01634-2022 (2023).

Kolb, M. et al. Nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and preserved lung volume. Thorax 72, 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208710 (2017).

Petnak, T., Lertjitbanjong, P., Thongprayoon, C. & Moua, T. Impact of antifibrotic therapy on mortality and acute exacerbation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 160, 1751–1763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.049 (2021).

Ley, B. et al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 156, 684–691. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00004 (2012).

Ryerson, C. J. et al. Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: The ILD-GAP model. Chest 145, 723–728. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1474 (2014).

Raghu, G. et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir Crit Care Med. 198, e44–e68. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST (2018).

Travis, W. D. et al. An official American thoracic Society/European respiratory society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 733–748. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant number 25K11428 received by YS) and a HUSM grant-in-aid from the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (grant number 655002-711311 received by YS)..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, resources, and writing—original draft. YS: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, resources, writing—original draft, funding acquisition, and final approval of the manuscript. MKono, SK, DH, and KY: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, resources, and writing—review & editing. YI, HY, HH, MKarayama, KF, NE, TF, and NI: Data curation, formal analysis, resources, supervision, and writing—review & editing. TS: Conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, and manuscript writing—original draft. All of the authors read the manuscript and approved to submit to Scientific Reports.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morikawa, K., Suzuki, Y., Kato, S. et al. Antifibrotic therapy in familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a comparative cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 43859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27730-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27730-2