Abstract

Liver cirrhosis poses a significant global health burden, with over 100 million cases worldwide and 2 million annual deaths. Despite advances in prognostic tools like MELD 3.0, their performance remains suboptimal. The pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV), a novel biomarker of systemic inflammation, has shown prognostic utility in chronic diseases but remains underexplored in cirrhosis. This study evaluates PIV’s predictive value for mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients and its synergy with MELD 3.0. Using data from the MIMIC-IV database, we analyzed 2,399 critically ill cirrhotic patients. PIV was calculated as neutrophils × platelets × monocytes/lymphocytes. Primary and secondary endpoints were 28-day and 365-day all-cause mortality, respectively. Multivariable Cox models, restricted cubic splines, and time-dependent ROC analyses, calibration curves, and clinical decision curve analyses were employed to assess associations and predictive performance. Patients in the highest PIV quartile (Q4) exhibited older age, more comorbidities, and worse metabolic profiles compared to Q1. PIV demonstrated a J-shaped association with mortality: Q4 had 0.51-fold higher 28-day mortality than Q1 (adjusted HR = 1.51, P < 0.001). The PIV-MELD 3.0 composite model outperformed individual markers, with AUCs of 69.5 (95% CI:0.68–0.71) (28-day) and 69.4 (95% CI:0.69–0.70) (365-day). Non-linear analysis revealed a J-shaped threshold effect with cut-off values of 3.33 (28-day) and 3.13 (365-day). Calibration curves and sensitivity analysis confirmed the superiority of the PIV combined with the MELD 3.0 model. Finally, sensitivity, subgroup, and external validation analyses further demonstrated the robustness of the association between PIV and mortality risk. PIV independently predicts short- and long-term mortality in cirrhotic patients, exhibiting a dose-response relationship. Integration with MELD 3.0 enhances risk stratification, offering a cost-effective tool for clinical decision-making. Prospective studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis represents a major global health challenge, with an estimated prevalence exceeding 100 million cases worldwide and causing approximately 2 million deaths annually, ranking as the 11th leading cause of global mortality1. In China alone, over 4 million cirrhosis cases are primarily driven by chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, though metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is emerging as a significant contributor2. The United States bears a substantial economic burden, with annual direct medical costs and indirect losses surpassing $32.5 billion3. Clinically, cirrhosis progresses from compensated to decompensated stages, manifesting life-threatening complications including portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which severely compromise patients’ quality of life and survival4. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease 3.0 (MELD 3.0) Integrating gender, bilirubin, serum sodium, and coagulation for assessing the severity and prognosis of patients with cirrhosis has shown superior discriminatory ability in previous studies5,6. But its performance is still suboptimal.

The pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV), calculated from neutrophil, platelet, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts, serves as a comprehensive biomarker of systemic immune-inflammatory activation with established prognostic value in malignancies and chronic diseases7. Emerging evidence demonstrates its clinical utility across diverse conditions: a U.S. cohort study revealed PIV’s predictive capacity for rheumatoid arthritis risk while highlighting its nonlinear association with mortality8. Furthermore, PIV independently correlates with mortality in hypertension, sepsis, and diabetes patients8,9,10. In gastrointestinal disorders, elevated PIV predicts poorer survival in colorectal cancer, suggesting its potential as a noninvasive marker for hepatic inflammation and fibrosis11. However, its application in cirrhosis, particularly for etiology stratification and decompensation prediction, remains insufficiently explored, representing a critical knowledge gap in hepatology research.

Leveraging data from the MIMIC-IV database and Chinese hospitals, this study aims to evaluate the prognostic value of PIV in predicting mortality risk among cirrhotic patients, addressing critical limitations of existing models such as MELD 3.0. We hypothesize that PIV, as a systemic inflammatory marker, will significantly enhance both short-term (28-day) and long-term (365-day) mortality prediction accuracy. By integrating PIV with MELD 3.0, our findings are expected to establish a more robust risk stratification system for critically ill cirrhotic patients, potentially improving clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

Methods

Study population

The MIMIC-IV database is a comprehensive, publicly available dataset containing de-identified health records from patients admitted to the intensive care units of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center12. It includes detailed clinical data such as demographics, laboratory results, vital signs, and treatment information. This database serves as a valuable resource for medical research, enabling studies on various critical illnesses and their management. By providing access to a large volume of high-quality data, MIMIC-IV supports the development of predictive models and the evaluation of clinical practices. One of the authors (Chengdong You) obtained access to the database and required data (Record ID: 62259600). Approval from the institutional review board was not required because the data were de-identified.

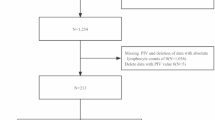

Our research group included patients diagnosed with cirrhosis, identified from the MIMIC database using ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes (ICD-9: 5712, 5715, and 5716, ICD-10: K703, K7030, K7031, K741, K742, K743, K744, K746, K7460, and K7469). The criteria for exclusion were: (1) age less than 18 years; (2) patients who are not first-time ICU admissions; and (3) absence of key laboratory values required to calculate PIV, including platelet count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and monocyte count. The final study cohort consisted of 2,399 patients (Fig. 1). These participants served as the derivation cohort in the study.

Data collection

Data extraction and processing were performed using PostgreSQL (version 16.0) with Structured Query Language (SQL), encompassing demographic characteristics (age, gender), vital signs [respiratory rate, temperature, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate, saturation of peripheral oxygen(SpO₂)], laboratory tests [sodium (Na), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), anion gap (AG), lactate (Lac), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose, creatinine (Cr), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), international normalized ratio (INR), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), red blood cell count (RBC), platelet (PLT), red cell distribution width (RDW), total bilirubin (TB), and albumin (ALB)], comorbidities [hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia (HLP), myocardial infarction (MI), malignant tumor, renal diseases, respiratory failure, and sepsis), and interventions/scoring systems (CRRT, liver transplantation, MELD 3.0, and SOFA). The MELD 3.0 score was calculated using its validated formula incorporating complex nonlinear relationships and interaction terms among gender, TB, INR, Cr, Na, and ALB. Calculators for MELD 3.0 are available at https://medcalculators.stanford.edu/meld. All laboratory and vital sign variables were extracted from the first available values obtained within 0–24 h after the patient’s admission to ICU as the baseline.

Variables with more than 20% missing values were excluded (Supplementary Table 1). Two data imputation methods, including the random forest algorithm and the 20-fold multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE), were employed to handle missing data.

Exposure and outcome

PIV was calculated using the following formula based on complete blood count parameters:

Due to the skewed distribution and outliers of the PIV, a natural logarithmic transformation (Log PIV) was applied prior to analysis, and participants whose calculated PIV values deviated by more than three standard deviations from the mean were excluded (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The primary endpoint of this study was 28-day all-cause mortality, while the secondary endpoint focused on 365-day mortality outcomes. Censoring is defined as patients who were still alive at the time of the last follow-up.

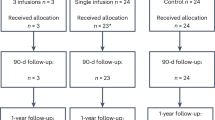

External validation

This study collected data from patients diagnosed with cirrhosis at the People’s Hospital of Xiushan County between June 2023 and May 2024. The outcome measure was all-cause mortality within 365 days, ascertained through telephone follow-up. Exclusion criteria included: (1) participants with missing PIV data, and (2) cases with undetermined 365-day mortality status. A total of 356 cirrhotic patients were ultimately included. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Xiushan County (Approval No: 2025XYLL005).

Statistic analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (normally distributed) or median with interquartile range (non-normally distributed), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%). Group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, or Chi-square test as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used in survival analysis to compare prognosis among different PIV quartiles.

After evaluating the proportional hazards assumption, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were employed with three sequential adjustments to assess the association between PIV and mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis: Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2 (adjusted for demographics and vital signs), and Model 3 (further adjusted for comorbidities, laboratory measures, and interventions). Restricted cubic splines (RCS) with four knots (5th、35th、65th、95th percentiles) were employed to visualize the dose-response relationship between PIV and mortality risk. Predictive performance was assessed through time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, comparing the combined PIV + MELD 3.0 model against individual indicators. In addition, Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) and Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI) were used to evaluate the incremental predictive value of MELD 3.0 + PIV for mortality risk. Subsequently, calibration curves and clinical decision curve analysis (DCA) were employed to evaluate the accuracy and clinical net benefit of different models in predicting mortality risk. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were performed to validate the robustness. Finally, we further validated the association between PIV and the 365-day mortality rate in patients with cirrhosis in the external validation.

R software (version 4.3.2) was used for all statistical analyses, and a two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Baseline information

This study enrolled a total of 2,399 critically ill patients with cirrhosis, of whom 1,530 were male and 869 were female (Table 1). Patients were divided into groups according to PIV quartiles (Q1-Q4). Patients in the highest quartile (Q4) were older, had higher respiratory rates, and heart rates and lower SBP and SpO₂ levels. Comorbidities such as hypertension, HLP, MI, respiratory failure, and sepsis were more prevalent in Q4. Laboratory test results revealed varying degrees of metabolic disturbances across different PIV quartiles, including elevated K, lactate, anion gap, BUN, Cr, ALP, and TB in Q4. Conversely, albumin levels decreased with increasing PIV. In addition, patients in the Q4 group used CRRT more frequently, received less liver transplantation treatment, and had higher MELD 3.0 scores. The differences in mortality rates among patients with varying PIV levels were also quite pronounced. The 28-day mortality rate for patients in the Q4 group was 2.2 times that of the Q1 group, and a similar trend was observed for the 365-day mortality rate.

Association between PIV and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses comparing all-cause mortality across patients stratified by PIV quartiles (Q1-Q4) were conducted (Fig. 2). Compared with groups having lower quartiles, the group with the highest PIV values (Q4) had significantly lower probabilities of survival at both the 28-day and 365-day follow-ups (log-rank P < 0.05).

To comprehensively evaluate the independent prognostic value of PIV in critically ill patients with cirrhosis, we constructed three adjusted Cox proportional hazards models (Table 2& Supplementary Table 2). For 28-day mortality, each 1-unit increase in PIV was associated with an increased risk across all models [Model 1: HR = 1.20 (1.15–1.26); Model 2: HR = 1.15 (1.10–1.20); Model 3: HR = 1.07 (1.02–1.12), all P < 0.05]. When analyzed by quartiles, patients in Q4 had a higher risk of death compared to those in Q1 by 2.51 times (Model 1), 2.02 times (Model 2), and 1.51 times (Model 3) (all P < 0.001). A similar pattern was observed for 365-day mortality, with PIV retaining independent predictive value after full adjustment [Model 3: HR = 1.04 (1.01–1.08), P = 0.021].

RCS analysis of the association between PIV and all-cause mortality

In Fig. 3, RCS analysis revealed a significant non-linear relationship between PIV levels and the risk of death (non-linear P for both endpoints was less than 0.05). For 28-day mortality, when PIV values were low, the change in mortality risk with increasing PIV was not very pronounced. However, once the PIV exceeds this range, there is a significant mortality response (non-linear P = 0.017). Similarly, for 365-day mortality, a risk association that was initially gradual and then steep was also observed within the range of PIV values (non-linear P = 0.048). Additionally, threshold-effect analyses identified a cutoff of 3.33 for the association between PIV and 28-day mortality and a cutoff of 3.13 for its association with 365-day mortality (Supplementary Tables 3 & 4).

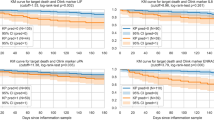

The incremental value of PIV in predicting mortality

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the MELD 3.0 + PIV composite score consistently demonstrated superior predictive performance in terms of both short-term (0–28 days) and long-term (0-365 days) mortality compared to the individual PIV or MELD 3.0 models. Time-dependent AUC analysis indicated that MELD 3.0 + PIV maintained strong discriminative power during both periods, outperforming the predictive capabilities of PIV or MELD 3.0 alone. Additionally, ROC curve analysis further corroborated these findings: MELD 3.0 + PIV achieved near-optimal discrimination for 28-day mortality (AUC%=69.5, 95% CI: 0.68–0.71), surpassing that of MELD 3.0 alone (AUC%=68.6, 95% CI: 0.69–0.70). This performance gap persisted for the 365-day outcome. In addition, compared to individual models, MELD 3.0 + PIV significantly improved reclassification and discriminative ability in Table 3: 28-day/365-day NRI increased by 0.265 and 0.265 respectively, IDI increased by 0.065 and 0.056 respectively (all P < 0.001, Table 3).

Additionally, the combined model of PIV and MELD 3.0 demonstrates superior comprehensive predictive performance and clinical net benefit compared to either model used alone (Supplementary Figs. 2 & 3).

Subgroup analysis

In terms of 28-day all-cause mortality, the prognostic impact of PIV showed similar effects in the major clinical subgroups (Fig. 5). In the vast majority of patients, PIV remained positively associated with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis (HR > 1.00). Interaction tests suggested that no significant interaction effects were found (P > 0.05 for all interaction effects). Similar findings were obtained in the 365-day mortality analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4), and these results suggest that the positive association between PIV and critically ill patients with cirrhosis was robust at the time.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses showed a strong correlation between PIV and the risk of death (Supplementary Tables 5, 6 & 7). After excluding cases of early death (≤ 7 days), PIV still had significant predictive value for 28-day mortality (Model 3 h = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.02–1.16, P = 0.006) and 365-day mortality (HR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.10, P = 0.024). Similar results were observed after excluding malignant tumor cases and performing MICE imputation, with PIV-Q4 demonstrating a strong positive association with mortality risk.

External validation

Finally, we conducted external validation using the database from Chinese hospitals. In the validation cohort, the baseline characteristics of patients across different PIV groups also demonstrated significant differences. Moreover, no significant differences were observed in the vast majority of clinical characteristics between the derivation and validation cohorts (Supplementary Tables 8 & 9).

Additionally, results from the multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the association between PIV and 365-day all-cause mortality remained statistically significant (Supplementary Tables 10 and Supplementary Fig. 5). In the fully adjusted model, a one-unit increase in PIV was associated with a 17% increased risk of mortality among critically ill patients with cirrhosis (95% CI = 1.06–1.30). Moreover, time-dependent AUC and ROC curves further confirmed that the predictive ability of PIV combined with MELD 3.0 for mortality in patients with cirrhosis was superior to that of PIV or MELD 3.0 alone. In terms of 365-day mortality risk, the external validation cohort also confirmed the significant advantage of the PIV + MELD 3.0 combined model (Supplementary Figs. 6 & 7).

Discussion

This study reveals a J-shaped relationship between PIV and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. By integrating PIV with the MELD 3.0 model, the predictive efficacy for mortality risk in cirrhosis patients is significantly enhanced, offering a more robust tool for early identification of high-risk individuals, particularly for short-term (28-day) and long-term (365-day) outcomes. These findings underscore the potential of PIV as a cost-effective, non-invasive biomarker to improve cirrhosis prognosis and alleviate healthcare burden.

Recently, there have been notable developments in understanding prognostic factors for individuals with cirrhosis. New biomarkers such as IL-6, uNGAL, and copeptin have shown excellent performance in predicting 90-day mortality risk, while a blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio (BCR > 27) can increase the risk of 180-day mortality by 45%13,14,15,16. In terms of nutritional indicators, the prognostic nutritional index has an AUC of 0.684 for predicting 3-month mortality and an AUC of 0.698 for predicting 6-month mortality in patients with hepatic encephalopathy17. Additionally, in the iteration of scoring systems, MELD 3.0, with a cutoff value of 18, has improved the AUC for predicting 2-year mortality to 0.783, significantly better than the traditional MELD (P < 0.05)18; the GEMA-Na score, through its gender-equitable design, achieves an AUC of 0.807 for female patients. Our study, for the first time, explores the association between PIV, an inflammatory marker, and mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Further results show that combining PIV with MELD 3.0 significantly outperforms the predictive capabilities of the two individual indicators. This finding will effectively promote the development of cirrhosis prognostic assessment from single indicators to multidimensional integration, providing more precise tools for clinical decision-making.

The elevation of PIV reflects excessive activation of the systemic immune system, which can lead to severe immune dysregulation in patients with cirrhosis19. This immune dysregulation not only weakens the patients’ defense against pathogens but also may trigger autoimmune reactions, further exacerbating hepatocyte damage and liver function deterioration, thereby increasing the risk of death20,21. Moreover, the increase in PIV is closely related to systemic inflammatory response, which can cause systemic vasodilation, hemodynamic instability, and multi-organ dysfunction, affecting vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, and lungs, and leading to severe complications like hepatorenal syndrome, cardiac insufficiency, and respiratory failure, significantly increasing the risk of death22,23,24. Meanwhile, the increase in inflammation is closely associated with the exacerbation of portal hypertension, which further intensifies portal hypertension, leading to complications such as esophageal variceal rupture, bleeding, and refractory ascites, significantly increasing the risk of death25,26. Therefore, the elevation of PIV can increase the risk of death in patients with cirrhosis through multiple mechanisms. These mechanisms interact with each other, jointly leading to the deterioration of the condition and the increase in the risk of death in patients with cirrhosis.

Certainly, several limitations in this study need to be clarified. Firstly, the study sample was predominantly sourced from patients with cirrhosis at one medical center, which may result in selection bias and restrict the generalization of the results to other groups. Second, the retrospective study design may lead to the absence of key clinical data and make it difficult to fully control for potential confounding factors. Third, as a dynamic inflammatory marker, PIV levels are susceptible to short-term factors such as acute infections and pharmacological interventions, which may affect the stability of the predictive model. Fourth, cirrhosis in this study was identified through ICD-9/10 coding, which may involve potential misclassifications. Fifth, the study did not conduct a competing risk analysis. Finally, the study mainly relied on the correlation analysis of laboratory indicators in critically ill patients with cirrhosis, lacking imaging data and other information to further elucidate the predictive role of PIV. Future research should further validate these findings through multicenter prospective cohort studies and integrate multi-omics analyses to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms of PIV in depth, thereby enhancing its application value in clinical practice.

Conclusion

In critically ill patients with cirrhosis, PIV showed a J-shaped association with their 28- and 365-day risk of death, and PIV combined with MELD 3.0 predicted the risk of death better than either PIV or MELD 3.0 alone. The study suggests that PIV might serve as a potential early risk assessment marker, but further prospective proportional-control studies are necessary to confirm the reliability of these findings.

Data availability

The MIMIC-IV data are openly available via PhysioNet (URL: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/). The Chinese validation cohort data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Devarbhavi, H. et al. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 79, 516–537 (2023).

Lu, K. et al. An analysis of the burden of liver cirrhosis: differences between the global, China, the united States and India. Liver Int. 44, 3183–3203 (2024).

Ma, C. et al. Trends in the economic burden of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis in the united states: 1996–2016. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 116, 2060–2067 (2021).

Premkumar, M. & Anand, A. C. Overview of complications in cirrhosis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 12, 1150–1174 (2022).

Ruf, A., Dirchwolf, M. & Freeman, R. B. From Child-Pugh to MELD score and beyond: taking a walk down memory lane. Ann. Hepatol. 27, 100535 (2022).

Mazumder, N. R. & Fontana, R. J. MELD 3.0 in advanced chronic liver disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 75, 233–245 (2024).

Lin, F. et al. Pan-Immune-Inflammation value: A new prognostic index in operative breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 830138 (2022).

Wu, B. et al. The relationship between the pan-immune-inflammation value and long-term prognoses in patients with hypertension: National health and nutrition examination Study, 1999–2018. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1099427 (2023).

Xu, H. B. et al. Association between admission pan-immune-inflammation value and short-term mortality in septic patients: a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14, 15205 (2024).

Su, Z. et al. Obesity indicators mediate the association between the aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Lipids Health Dis. 24, 176 (2025).

Yang, X. C. et al. Prognostic value of pan-immune-inflammation value in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 12, 1036890 (2022).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10, 1 (2023).

Ikeda, Y. et al. Serum pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 level is predictive of further decompensation and mortality in liver cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 55, 696–706 (2025).

Barreto, R. et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated Lipocalin predicts kidney outcome and death in patients with cirrhosis and bacterial infections. J. Hepatol. 61, 35–42 (2014).

Sola, E. et al. Plasma copeptin as biomarker of disease progression and prognosis in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 65, 914–920 (2016).

Yi, Y., Li, L., Chen, Y. & Luo, Y. Interaction between age and blood Urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio on mortality in patients with severe cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC database. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 16, 1544223 (2025).

Xie, Y., He, C. & Wang, W. Prognostic nutritional index: A potential biomarker for predicting the prognosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis. Front. Nutr. 9, 1092059 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Improved discrimination and predictive ability of novel prognostic scores for Long-term mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. (2025).

Okyar Bas, A. et al. Pan-immune inflammation value; a novel biomarker reflecting inflammation associated with frailty. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35, 1641–1649 (2023).

Jiang, R., Hua, Y., Hu, X. & Hong, Z. The Pan immune inflammatory value in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatic fibrosis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 48, 102393 (2024).

Tilg, H., Adolph, T. E., Dudek, M. & Knolle, P. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the interplay between metabolism, microbes and immunity. Nat. Metab. 3, 1596–1607 (2021).

Lange, C. M. Systemic inflammation in hepatorenal syndrome - A target for novel treatment strategies? Liver Int. 39, 1199–1201 (2019).

Murat, B. et al. Association of Pan Immune-Inflammation value with long term outcomes of acute decompensated heart failure. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 121, e20230817 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Tan, X., Hu, S., Cui, Z. & Chen, W. Relationship between systemic Immune-Inflammation index and risk of respiratory failure and death in COPD: A retrospective cohort study based on the MIMIC-IV database. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 19, 459–473 (2024).

Mehta, G. et al. Inflammation and portal hypertension - the undiscovered country. J. Hepatol. 61, 155–163 (2014).

Arroyo, V. et al. G.C. investigators from the Easl-Clif Consortium, and F. European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver, The systemic inflammation hypothesis: Towards a new paradigm of acute decompensation and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 74 670–685. (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhu L: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft; Li P: Methodology, Validation; You C: Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the MIT and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center IRBs (MIMIC-IV data) and the People’s Hospital of Xiushan County Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2025XYLL005). The MIMIC-IV database provided anonymized data with waived consent, while the Chinese cohort obtained written informed consent. All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Li, P. & You, C. Pan immune inflammation value improves MELD 3.0 for mortality prediction in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Sci Rep 15, 43963 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27731-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27731-1