Abstract

Given the known central role of porphyrins in the photosynthesis, in this work, manganese (III) meso-tetrakis(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin (MnTNPP) is used for the first time as a visible antenna for TiO2 nanoparticles. The crystalline TiO2 nanoparticles in pure anatase phase with high specific surface area (290 m2/g) were prepared from aqueous TiCl3 precursor and citric acid. A pyridyl linker in surface-bound TiO2 (SAPy), which forms a strong coordination bond with the Mn center of porphyrin complex (MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2), significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity. The photoactivity of the as-prepared hybrid was found to be approximately 6 and 4 times greater than that linker-free MnTNPP@TiO2 toward the degradation of Rhodamine B and methyl orange respectively, under low intensity visible light 40 W CFL irradiation. Based on the XRD patterns TiO2 retained its pure anatase phase after modification with MnTNPP/SAPy complex, while its specific surface area decreased to 70 m2/g and its band gap reduced to 2.6 eV making it a visible-light responsive photocatalyst. A faster degradation was observed for negatively charged dyes caused by electrostatic attraction between the positively charged photocatalyst and the pollutant. Quenching of the PL intensity of bare TiO2 by 87% after functionalization with SAPy/MnTNPP obviously showed the efficient electron − hole separation resulting from transmitting photoexcited electrons from the light-absorbing porphyrin sensitizer into the conduction band of TiO2 through the SAPy linker acting as an effective molecular wire. The effect of scavengers was studied and photogenerated hole was found as main active species for oxidative degradation of dyes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental pollution, driven by industrialization, adversely affects ecosystems, biodiversity, and human health. Industries such as leather, textiles, pharmaceuticals, and paper printing release substantial toxic compounds into water bodies, compromising water quality, which in turn harms aquatic life1,2. This has led to scientific efforts focused on environmental remediation through wastewater treatment3,4. Several physicochemical methods such as adsorption, filtration, chemical coagulation, precipitation, bacterial treatment, electrochemical approaches, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are utilized to remove pollutants5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Among these, AOPs are particularly promising due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency in degrading pollutants into less harmful CO2 and H2O. AOPs involve the absorption of visible light by a photocatalyst, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) to accelerate pollutant degradation. An efficient photocatalyst is designed to enhance light absorption and electron transfer, ensuring effective solar energy conversion12,13.

In the realm of nanoscale materials, distinct optical and electronic properties emerge, depending on the size and shape of photoactive components. Photocatalytic processes offer notable advantages, leading to extensive research on various organic and inorganic nanomaterials for wastewater remediation. Notable examples include ZnO14, TiO215 and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)16, along with other materials such as zeolites17, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)18, bismuth-based photocatalysts19, carbon quantum dots (CQDs)20, fullerene21, graphene oxide (GO)22, reduced graphene oxide (RGO)23, and porphyrin-based nanostructures24.

Among these, TiO2 and related materials stand out as promising photocatalysts due to their high stability, low toxicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficient degradation of hazardous chemicals in water. However, their relatively large bandgap (~ 3.2 eV) limits their ability to absorb visible light from the solar spectrum, resulting in suboptimal photocatalytic efficiency. As a result, a large amount of catalyst is required to achieve efficient pollutant degradation during the photocatalytic process25.

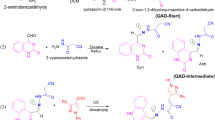

Porphyrinoids (including free-base porphyrins and metalloporphyrins) exhibit a high absorption coefficient in defined spectral regions: 400–440 nm (Soret band) and 500–720 nm (Q bands), covering full visible light region making them suitable for sensitizing the semiconductors such as TiO226,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. In most cases 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(carboxyphenyl)porphyrin or/and metalated complexes chemically linked to the TiO2 surface through carboxylic groups26. Once the carboxylic groups are at the para and meta position of the phenyl groups, the free-base porphyrins only could be anchored to the TiO2 by one or two of its groups lying perpendicular to the metal oxide surface making an improvement in the photocatalyst performance of the TiO241. While for their metalloporphyrin anchoring seems to occur on a non-planar configuration, thus there is no effective electron coupling between them and the semiconductor34. However, interaction between the hydroxyls of TiO2 nanoparticles and metal center of porphyrins may favor the electron transfer between the porphyrin molecules and the TiO2 nanoparticles as reported for TiO2/SnHTPP40. Encouraged by this, recently we prepared an anchoring pyridyl ligand (SAPy) by condensation of (3-oxopropyl)trimethoxysilane and 4-aminopyridine (Fig. 1)42, for coordinatively anchoring of M(III)Salophen complexes (M=Fe, Mn) to promote the photocatalytic activity towards dyes degradation43. Pyridyl linker function as effective molecular wires, transmitting photoexcited electrons from the light-absorbing porphyrin sensitizer into the conduction band of TiO244. The results were promising particularly for Mn(III)Salophen induced us to assess the sensitizing effect of Mn(III) porphyrins (Fig. 1). In the previous work we used a mixture of TiO2 crystallographic phases as anatase–rutile, which acts as a doped/composite material reduces the recombination rate of electron–hole pairs making it a more active photocatalyst than the pure TiO245. The notable photocatalytic activity of core (anatase/rutile) downplays the sensitizing role of coordinated complexes (Salen and porphyrins). Thus, in this work, a pure anatase phase of TiO2 is prepared according to our modified procedure using aqueous TiCl3 precursor and citric acid serving as a slow-release agent for Ti3+ ions46 .Among different porphyrin complexes manganese(III) 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-nitrophenyl)porphyrin (MnTNPP) is used for the photosensitization of TiO2 nanoparticles into the visible region (Fig. 1). The presence of nitro groups induces electron deficiency in the porphyrin ring, enhancing its oxidative stability while also reinforcing the coordination anchoring via the pyridyl ligand (SAPy)26. This water-insoluble porphyrin complex eliminates errors arising from the homogeneous photocatalytic activity of leached metalloporphyrin in aqueous solution47. In contrast to 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin, the nitro groups on the porphyrin ligand of MnTNPP do not establish covalent bonds with the functional groups on the TiO2 surface, making coordination anchoring through the pyridyl linker the dominant interaction. However, non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, may enhance the adhesion of MnTNPP to the TiO2 surface48. Finally, monitoring the presence of MnTNPP on the TiO2 surface during the reaction, is straightforward through the characteristic stretching of the –NO2 group in the FT-IR spectra. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one reported instance of using metal-free meso-tetra(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin for the decoration of the surface of TiO2 for dye degradation48 and no evidence of its metal complexes being utilized for this purpose. However, in that report, the graphene sheets should be combined closely with TiO2 nanowires to inhibit the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs48. There are engaging and challenging findings on the photocatalytic activity of (M)porphyrin-modified TiO2 towards organic dyes as representative pollutants26, which motivated us to assess the photocatalytic activity of the as-prepared nanohybrid in dye degradation. The resulted hybrid nanomaterial MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 acts as a visible-light responsive and robust photocatalyst for different organic dyes including cationic and anionic dyes using H2O2.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of photocatalyst

Figure 1 delineates the step-by-step fabrication of the MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 composite using its components42,49,50,51. UV–Vis spectra of the as-prepared TNPPH2 ligand and its Mn(III) complex, Mn(III)TNPP(OAc), are given in Fig. S4. The Soret absorption band of ligand located at 425 nm shifted to 465 nm after complexation with manganese and the four Q bands at 515, 552, 592 and 650 nm reduced to two peaks at 565 and 600 nm indicating that the manganese (III) ion was successfully embedded into porphyrin ring51. The surface of the TiO2 nanoparticles was functionalized with SAPy to establish a coordination bond with Mn center of MnTNPP. To approve this hypothesis, SAPy was removed from the synthetic protocol and the resulting composite MnTNPP@TiO2 (see Fig. S3 for FT-IR spectra) released easily the loaded MnTNPP after sonicating in ethanol evidenced by UV–Vis spectra of filtrate (Fig. S4). It can be concluded that the nitro groups on the porphyrin ring have minor sharing in the binding of MnTNPP to TiO2 nanoparticles most probably by weak hydrogen bonding, as molecule orientation of para-substituted porphyrin creates the distance of the porphyrin molecule to the TiO2 surface (Fig. 2)34,41,53,54.

The FT-IR spectra for TiO2 and SAPy are given as Figs. S1 and S2 respectively, in SI and comparative spectra of SAPy@TiO2, MnTNPP and MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 are presented in Fig. 3. The FT-IR spectra of MnTNPP showed the stretching of –NO2 group at 1343 and 1516 cm−155. The moderately strong bands located at 1595 and 1657 cm−1 attributed to C=C and C=N vibrational bands of porphyrin ring55,56. The successful synthesis of SAPy@TiO2 was evidenced by advent of characteristic peaks in three regions. The frequency of C=N bond of SAPy Schiff base compound located at 1654 cm−1, the Si–O bond stretching at 1130 and 1025 cm−142 and Ti–O stretching at 500–700 cm−157. After attachment of MnTNPP to SAPy@TiO2, the stretching vibrations of nitro group shifted slightly (2–4 cm−1) to 1345 and 1520 cm−1 suggesting the presence of the unbound terminal nitro group. Nevertheless, C=N bond stretching of SAPy shifted noticeably to 1630 cm−1 caused by coordinative anchoring of SAPy to MnTNPP. The presence of Si–O and Ti–O bands in the spectra of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 provided further evidence for successful fabrication of title composite.

Further support for immobilization of MnTNPP on TiO2 was found by nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and the corresponding pore size distribution curves for bare TiO2 and MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 at 77 K (Fig. 3B,C). The isotherms in Fig. 3B exhibit a type II profile with an inflection point at P/P₀ = 0.990, indicative of a type H3 hysteresis loop, which is characteristic of mesoporosity in both the pure TiO2 and MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 samples58. Decreased specific surface area of bare TiO2 from 290 to 70 m2/g along with an increase in its average pore size from 1.64 nm to 2.38 nm (BJH) after functionalization with MnTNPP verified the effective coverage of TiO2 surface by MnTNPP.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to examine the influence of incorporation of manganese porphyrins on the crystal structure of TiO2. Figure 3D presents the XRD patterns of both TiO2 and the MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 composite with no discrepancy between the samples indicating that TiO2 preserved its crystalline structure during surface modification. The advent of diffraction peaks at 25.3°, 37.9°, 47.9°, 54.2°, 62.5°, 69.7°, 74.9°, and 82.4° correspond to a pure anatase phase of TiO2 (JCPDS no. 21–1272)59.

The thermal stability of the sample was assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min, spanning from room temperature to 900 °C under air. The TGA-DTG (differential thermogravimetry) curves, depicted in Fig. 3E, revealed the stability of the fabricated composite up to 250 °C. A 5% initial weight loss before 200 °C attributed to the desorption of physiosorbed small molecules and humidity. A second weight loss (19%) up to 600 °C corresponds to the combustion of porphyrin moieties and the silane anchoring group connected to TiO2. The weight loss observed at elevated temperatures can be attributed to formation of Ti and Si oxides.

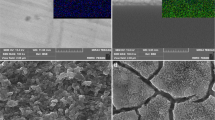

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the composite revealed spherical morphology with an average diameter of 20 nm with some aggregation (Fig. 4). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) spectra and elemental mapping presented in Fig. 4 confirmed the presence of composed elements including C, N, O, Si, Mn and Ti as well as their uniform spatial distribution of these elements in the fabricated composite. The inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis of Mn content revealed 0.5 mmol/g Mn in the as-prepared MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 composite corresponding to 2.8% MnTNPP.

Photophysical properties

UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) show the characteristic absorption bands of TiO2, SAPy@TiO2 and MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 (Fig. 5A). The advent of S-band of MnTNPP at 470 and two Q-bands at 532 and 653 nm in the DRS of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 confirmed the presence of MnTNPP in the fabricated nanocomposite (see Fig. S4)51. Moreover, a red shift of the Soret band from 463 to 470 nm provided further evidence for formation of axial coordination complex between Py ligand of SAPy and metal center of MnTNPP60. The comparative DRS clearly shows that the anchoring of the MnTNPP on the functionalized TiO2 nanoparticle increases significantly the absorption in the visible region. To determine the band gap energies of the as-prepared materials, the UV–Vis spectra in diffuse reflectance mode (R) were converted to the Kubelka–Munk function, F(R), to decouple the extent of light absorption from scattering. The band gap energies were derived from the plot of the modified Kubelka–Munk function, (F(R)E)^(1/2), against the energy of the absorbed light according to Eq. 1 (Fig. 5B).

The band gap energy of bare TiO2 decreased upon subsequent functionalization with SAPy and especially MnTNPP, ultimately reaching 2.6 eV for MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2. The effective carrier’s separation in the heterojunction MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 hybrid as a key factor in improving photocatalytic activity was evaluated by photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. Quenching of the PL intensity (excited at 355 nm) of bare TiO2 by 52 and 87% after functionalization with SAPy and SAPy/MnTNPP respectively, obviously showed the efficient electron − hole separation resulting from the charge transfer between the TiO2 core and MnTNPP through the SAPy linker and is expected to increase the photochemical activity of the fabricated hybrid (Fig. 5C)43.

Adsorption

The removal efficiency of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 was evaluated for the degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) dye as a model contaminant. Since the surface adsorption is the initial stage of the degradation process, initially, a period of 60 min was required to reach the adsorption–desorption equilibrium, where 0, 3, 5 and 11% of RhB were respectively adsorbed by 5 mg of TiO2, SAPy@TiO2, MnTNPP and MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2. Given the reduced surface area of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 composite (70 m2/g) than that of TiO2 (290 m2/g), the more adsorption of RhB molecules on the composite raised some queries regarding its causes. The surface charge of composite is the first thing that comes to mind and accordingly the adsorption of structurally and electronically different dyes were examined and the results are depicted in Fig. 6A. In acidic media, the surface of bare TiO2 is typically positively charged (isoelectric point, IP = 5–7)61 and after being coated with MnTNPP, the isoelectric point shifts to 3.3 (Fig. S5). As a result, at the pH of 3 used in this work, the surface of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 carries a little positive charge (Fig. S5), amenable it to adsorb negatively charged dyes such as methyl orange (MO, 47%). Thus, the moderate adsorption of neutral methyl red (MR, 37%) and limited adsorption of positively charged dyes such as RhB (11%), crystal violet (CV, 19%) and methylene blue (MB, 22%) can be assigned to non-covalent interactions including hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions between polycyclic structure of the organic dye and porphyrin rings of the photocatalyst62.

(A) Adsorption of different dyes on the surface of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 at pH = 3 (RhB: rhodamine B, CV: crystal violet, MB: methylene blue, MR: methyl red, MO: methyl orange); (B) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB dye under irradiation of various light sources in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 (UVC, UVA, CFL, Blue LED, , Reptile) and (C) in the presence various catalyst under CFL light; (D) Time course photodegradation of RhB under CFL light in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 and inset represents pseudo-first-order kinetic. The reactions were run three times using a 50 ml aqueous solution with pH = 3 containing 2 ppm RhB, 5 mg (A, B, C) and 10 mg (D) catalyst and 62 µl H2O2 at 298 K.

Photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB)

After reaching the adsorption–desorption equilibrium, the RhB solution was subjected to lights under optimized condition used for our previous work43. Fifty milliliters of an aqueous solution of 2 ppm RhB with pH 3 exposed to different light sources including UVC T8 (15 w) , UVA Actinic BL (TL-D 15 w), reptile lamp, LT NARVA (18 W, full range visible light + 4% UV), blue LED, AC86, Z.F.R (12 W, λmax = 505 nm) and a CFL lamp (40 W, full range visible light with λmax = 546 and 611 nm) were examined. As depicted in Fig. 6B, the highest photodegradation was obtained under the UV lights as expected for TiO2 as a UV-response photocatalyst due to its wide band gap25. Nevertheless, the desired photocatalyst is one that can be used under visible light because the sunlight is mainly composed of visible light. The CFL light as a safe full spectrum visible light source (Fig. S6) induced slightly TiO2 towards photodegradation of RhB (22%/120 min, Fig. 6C) thus, can be a good candidate to assess accurately the photosensitizing effect of MnTNPP on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 in visible region. The initial results in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 showed 50% photodegradation of RhB at the same time while less activity of 19 was observed for free complex MnTNPP confirmed the synergistic effect between porphyrin complex and TiO2 nanoparticles in the fabricated nanohybrid. Further control experiments showed negligible degradation of RhB in the absence of either visible light or the MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 photocatalyst (< 5%) (Fig. 6C), confirming that both of them are inevitable for the degradation process. Removing H2O2 reduced the degradation percentage to 20% featuring that the photocatalyst requires an oxidant to complete its cycle. Less activity was observed for porphyrin ligand TNPP (13%) as well as SApy@TiO2 (25%) under these conditions. More important result is the ineffectiveness of linker-free composite MnTNPP@TiO2 (7%) confirming the key role of SAPy linker for improving the photocatalytic performance of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 caused by charge transfer between MnTNPP and TiO2 evidenced by PL spectra62. Further examination was carried out to improve the DC%. Increasing the pH beyond 3 led to a reduction in DC%, with values decreasing to 45, 40, and 29 at pH levels of 4, 5, and 6, respectively. This trend aligns with the diminished adsorption of deprotonated RhB on the negatively charged surface of the photocatalyst (IP = 3.3)63. A little effect was observed for further amount of H2O2 (58%/120 min for 100 μL H2O2), nevertheless, an increase in the catalyst amount by 10 and 15 mg accelerate the degradation to 72 and 78% after 120 min due to increasing the number of active sites of the catalyst with respect to concentration of RhB. DC% results obtained from three repeated runs of the RhB degradation under optimized conditions (10 mg catalyst and 62 µl H2O2 at 298 K under a 40 W CFL light) are given in Fig. S7. The average conversion was 72% after 120 min, with a standard deviation of ~ 7%, indicating high reproducibility.

The decreased absorption in UV–Vis spectra accompanied a significant hypsochromic shift indicate that the deethylation process competes with cleavage of the conjugated chromophore structure during the overall degradation process (Fig. 6D). Under the experimental condition, the RhB solution left the 28% of the original concentration, while there was 56 nm hypsochromic shift after 120 min irradiation under CFL light. The advent of maximum wavelength at 540, 524, 510 and 500 nm after 40, 80, 100 and 120 min irradiation indicate the step by step losing of ethyl groups of RhB transforming it to N,N,N-Triethylrhodamine, N,N-Diethyl-rhodamine, N-Ethyl-rhodamine and Rhodamine intermediates, respectively (Fig. 6D)64. Detection of N-ethyl-rhodamine (λmax 510 nm) in the mixture of the reaction by mass spectrometry (MS, m/z = 355) provided further support for deethylation process (Fig. S8). The adsorption mode of RhB on the surface of photocatalyst greatly influence the photocatalytic degradation mechanism. In addition to π–π interactions between polycyclic structure of the organic dye and porphyrin rings, the positively charged diethylamino groups of RhB molecules can interact with nitro groups of porphyrin unit to facilitate the adsorption on the surface of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2. Therefore, active oxygen species predominantly attack the auxochromic groups and induce the deethylation of the alkylamine group65.

To explore whether the decomposition of RhB obeyed a pseudo-first-order kinetics which is well recognized for organic compound degradation in the occurrence of heterogeneous photocatalysts was investigated66. The curve with eqn. Ln (Ct/C0) = kt exhibited good linear performance (R2 = 0.96), exposes that degradation kinetics reaction is controlled dominantly by a pseudo-first-order reaction. The apparent rate constant of 0.006 min−1 was found under 40 W CFL lamp which is higher than that of a metal-free porphyrin catalyst TCPP-TiO2 (TCPP = tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin), under 90 w CFL irradiation at pH = 6 (0.0052 min-1) and particularly under UV-A (0.0045 min−1) at pH = 435. To be honest, the comparison of catalytic activity of a photocatalyst with those reported in the literature is difficult due to the limited data for relevant systems and different reaction conditions used. The dye structure and concentration, the choice of metal-free porphyrins rather or metal complexes as sensitizers, along with variations in pH and light sources of differing wavelengths and intensities, present significant challenges for making precise comparisons (Table S1).

Effect of the dye structure

The optimized conditions were employed to assess the photocatalytic potential of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 in the degradation of different dyes including cationic MB and CV as well as neutral MR and anionic MO under CFL bulb (Fig. 7A). As depicted in Fig. 7A, while the DC% of cationic dyes CV and MB reached ultimately to 42 and 53% respectively, after 180 min, MR as a neutral dye and particularly anionic MO faded entirely at 120 and 60 min respectively. Given the surface adsorption is the initial stage of the degradation process, more effective adsorption of MR (37%) and MO (47%) onto MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 (Fig. 6A) provide more effective degradation of dyes. The molecular structure of a dye also plays a crucial role in its degradation. Azo dyes like MO and MR are more prone to oxidative and photodegradation processes, whereas dyes containing a xanthene ring (RhB), phenothiazine (MB), and especially those with a triphenylmethane structure (CV) exhibit greater resistance to photodegradation. Another important factor that should be considered is pH that affects the electrostatic interactions between the molecules on the surface of the photocatalyst and the dye molecules, thus, the adsorption capacity of the catalyst is altered as mentioned above67. The impact of pH varies among different dyes, influenced by their chemical structure and pKa value. It is known that MO degradation is more efficient in an acidic medium (pH ∼3) due to the better sensibility of the protonated form of the dye for the oxidation process68. Control experiments demonstrated that MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 exhibited superior photocatalytic efficiency towards MO degradation compared to its individual components under CFL light (Fig. 7B) confirming once again SAPy combined with MnTNPP as an effective modifier of TiO2 for visible light photocatalysis. The first-order degradation rate constant for MO in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 was determined to be 0.049 min−1 (Fig. 7C) which is much higher than those reported for porphyrin-based MOF composites (0.0014 to 0.0042 min−1)69 and FeTPP/TiO2/Polymer (0.00085 to 0.0049 min−1) (Table S1)70.

(A) Photodegradation of different dyes in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 at pH = 3 (RhB: rhodamine B, CV: crystal violet, MB: methylene blue, MR: methyl red, MO: methyl orange). (B) The effect of different catalyst on photodegradation of MO under CFL light and (C) Time course photodegradation of MO under CFL light in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 and inset represents pseudo-first-order kinetic. (D) Scavenging analysis of photodegradation of MO in the presence of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 under CFL light using 5 mg scavengers (AO: ammonium oxalate, p-BQ: p-benzoquinone, BHT:2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol). The reactions were run using a 50 ml aqueous solution with pH = 3 containing 2 ppm MO, 10 mg catalyst and 62 µl H2O2 at 298 K.

Mechanistic aspects

To detect the photo-generated reactive species during the photocatalytic degradation of MO dye, radical trapping experiments were conducted. Significant reduction in DC% of RhB and MO to ~ 20% under H2O2-free condition at the best reactions times (Figs. 6C and 7B) showed that H2O2 acts as electron scavenger and thus confirmed the major influence of photogenerated electron in the mechanism. Further scavengers such as tert-butanol (tBuOH), p-benzoquinone (BQ) and ammonium oxalate (AO) were also employed as scavengers for OH., O2–, and h+ respectively. Figure 7D indicates that the removal efficiency of MO is 91, 30 and 21% in the presence of TBA, BQ, and AO under light irradiation for 60 min, respectively. Subsequently, OH. imposes a minor influence on the removal of MO, while h+, O2– impose a major influence in the presence of the title photocatalyst. Eliminating dissolved oxygen under a nitrogen (N₂) atmosphere led to a slight change in the DC% of MO (11%), ruling out the involvement of O₂ in the degradation mechanism, which typically occurs through reduction to O2– by photogenerated electrons. The partial reduction of DC% (15%) in the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT, Fig. 7D) as a hindered scavenger for radicals in solution, provided further evidence for trace amount of O2– in solution. Thus, the reduced DC% in the presence of BQ can be assigned to its reaction with H2O2 which has been shown to proceed with consumption of both reactants with second order rate constants71. Based on these observations, following mechanism is postulated as depicted in Fig. 8. The LUMO level (ELUMO) of the MnTNPP was determined using its first reduction onset potential (ERed = − 0.556 V)72, The ELUMO onset value in volt is converted to energy level in electron volt according to the reference standard, for which 0.0 V versus RHE (reversible hydrogen electrode) equals − 4.44 eV versus Evac (vacuum level)73. Then, the EHOMO was calculated by adding the band gap value (2.53 eV estimated from tauc plot, Fig. S9) of MnTNPP to ELUMO74. The VB and CB of anatase TiO2 energy level have been reported as − 7.35 and − 4.15 eV75. Photoexcited electrons in the LUMO of MnTNPP are migrated to the CB of TiO2 through the SAPy linker, where H2O2 is reduced to H2O in acidic media (pH = 3). The photo-excited h+ in the TiO2 is transferred to the HOMO of the MnTNPP to oxidize and degrade the dyes to small molecules evidenced by MS spectra of degraded molecules of RhB (Fig. S8) and MO (Fig. S10)76,77,78,79.

Heterogeneity and reusability assessment

Given the critical importance of photocatalyst reusability for practical applications, we assessed the recyclability of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 in the degradation of MO (Fig. 9A). MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 retained a high degradation efficiency and almost the reproducible kinetic even after five consecutive cycles, exhibiting only a 6% decrease in performance. This minimal reduction underscores the exceptional stability of the MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 photocatalyst which was further supported by heterogeneity test and FT-IR analysis (Fig. 9B,C). The catalyst was removed after 30 min when 53% of MO was degraded. Subsequently, the reaction was allowed to proceed further. As depicted in Fig. 9B, the filtrate exhibited minimal activity, achieving a conversion of 19% during further 70 min. The ICP-OES analysis of the used catalyst revealed 2.65% Mn indicating a negligible amount of leaching (5.3%) during the degradation reaction. These findings confirm that the catalyst operated heterogeneously throughout the reaction. FT-IR spectra of the used MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 revealed spectra nearly identical to those of the pristine photocatalyst (Fig. 9C), indicating the structural integrity of catalyst during the photocatalytic reaction. Thus, the surface modification of TiO2 via SAPy bridging significantly enhances the adhesive strength of MnTNPP photosensitizers and optimizes the surface properties. During the photocatalytic process, the bridging–anchoring groups likely inhibit the detachment of MnTNPP from the modified TiO2 surface. This robust adhesion between MnTNPP and SAPy@TiO2 not only increases the quantity of MnTNPP attached to the SAPy@TiO2 surface but also facilitates the electron transfer from excited MnTNPP to the conduction band of TiO2 as were supported by using linker-free hybrid MnTNPP@TiO2 in previous sections (Fig. S4 for leaching and 6C and 7B for photocatalytic performance). These results were further corroborated when MnTNPP was replaced by unsubstituted manganese (III) meso-Tetraphenyl porphyrin [Mn(TPP)OAc] as well as electron-rich manganese (III) meso-tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl) porphyrin [Mn[T(4-OMeP)P]OAc]. Both photocatalysts, Mn(TPP)OAc/SAPy@TiO2 and Mn[T(4-OMeP)P]OAc/SAPy@TiO2 accelerated the RhB photooxidation so that faded it almost completely in less than 15 min (Fig. S11). Nevertheless, they lost their activity at the subsequent run (30 and 22% RhB degradation respectively after 120 min) resulting from destruction of porphyrin structures during oxidation reactions evidenced by FT-IR spectra (Fig. S12). These findings validated our rationale for using MnTNPP as an electron-deficient porphyrin complex, as it not only improved oxidative stability26, but also strengthened coordination anchoring through the pyridyl ligand (SAPy).

The superior photocatalytic activity of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 system than that of utilizing metal-free TNPP as sensitizer48, is obvious. Besides, the electron transfer function of SAPy linker, the metal ions coordinated with porphyrin strongly influence the sensitization of porphyrin. This effect may be ascribed to the difference in the photogenerated electron injection from the excited porphyrin molecules to the conduction band of TiO2 induced by the metal ions32. Additional benefits of this study were identified through comparisons with previous works reported for MO degradation (Table S1). The key distinctions include the reliance on high intensity (300–500 W) and often unsafe light sources over extended reaction times.

Conclusion

Pure anatase phase TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by TiCl3 and citric acid serving as a slow-release agent for Ti3+ ions sensitized by Manganese (III) meso-Tetrakis(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin through a pyridyl linker for improving the visible-light response of TiO2. The sample was characterized by different techniques. The XRD patterns revealed a pure anatase phase before and after decoration with MnTNPP/SAPy complex while the specific surface area decreased from 290 to 70 m2/g and its band gap reduced to 2.6 eV confirming the effective connection between the core and shell materials. Photocatalytic activity of the as-prepared catalyst was initially assessed by its efficiency to remove RhB under low intensity visible light irradiation which was 6 times greater than that linker-free MnTNPP@TiO2 highlighting the key role of pyridyl linker in electron transfer between TiO2 core and porphyrin sensitizer. The results were more promising for neural and particularly negatively charged dyes caused by electrostatic attraction between the positively charged photocatalyst and the pollutant. Quenching of the PL intensity of bare TiO2 by 87% after functionalization with SAPy/MnTNPP obviously showed the efficient electron − hole separation resulting from transmitting photoexcited electrons from the light-absorbing porphyrin sensitizer into the conduction band of TiO2 through the SAPy linker acting as an effective molecular wire. Spectral evidences revealed that the deethylation process competes with cleavage of the conjugated chromophore structure during the overall degradation process of RhB. Scavenging experiments led to a proposed mechanism in which H2O2 attracts photogenerated electrons, rendering the photogenerated hole the active species responsible for the oxidative degradation of dyes. We believe this study paves the way for visible-light-driven degradation of other common pollutants, including antibiotics and phenol derivatives, utilizing the high-performance MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2/H2O2 photocatalyst system.

Experimental

Materials: Titanium(III) chloride (about 15%, Merck), Citric acid (99.5%, Merck), Ethanol (≥ 99.5%, Merck), (3-Chloropropyl)trimethoxysilane (≥ 97%, Sigma-Aldrich), Dimethyl sulfoxide (≥ 99.9%, Merck), Sodium hydrogen carbonate (99.7%, Merck), Diethyl ether (≥ 99.7%, Merck), Magnesium sulfate anhydrous (98%, Merck), 4-Aminopyridine (98%, Acros Organics USA), 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde (98.5%, Loba Chemie), Acetic anhydride (≥ 98%, Merck), Propionic acid (≥ 99%, Merck), Pyrrole (≥ 97%, Merck), Pyridine (≥ 99%, Merck), Acetone (≥ 99.8%, Merck), N,N-Dimethylformamide (≥ 99%, Merck), Manganese(II) acetate tetrahydrate (99%, Merck), Dichloromethane (≥ 99%, Merck), Methanol (99.9%, Merck), Hydrogen peroxide (25% solution in water, Merck), Rhodamine B (Merck), Methyl orange (Merck), Crystal Violet (Merck), Methylene Blue (Merck), Methyl red (Merck), Ammonium Oxalate (99.5%, Merck), p-Benzoquinone (98%, Merck), tert-Butyl alcohol (99.5%, Merck), 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (99%, Merck). All purchased chemicals were used without further purification except for pyrrole which was purified by distillation immediately before use.

Instrumentation

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) was conducted using a ZEISS Sigma 300-HV, equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained from KBr pellets using a Shimadzu 800 FT-IR spectrometer. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectra were recorded with a V670 JASCO spectrophotometer. Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) measurements were performed on a Bruker D8-Advance X-ray diffractometer utilizing Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was carried out using a Varian ICP-OES 730-ES instrument. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured with a Belsorp-mini II (Bel Japan). Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TGA-50 Shimadzu apparatus at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under air. UV–Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) analyses were performed using an Avaspec-2048-TEC spectrophotometer (Avantes) over the range of 300 − 800 nm, with BaSO4 as the standard reference. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were recorded on an RF-5301DCM Shimadzu instrument.

Preparation of TiO2 powder

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) powders were synthesized as previously reported46. In a typical synthesis, 1 mL of titanium trichloride (TiCl3, 7.84 mmol) was dissolved in 2.5 mL of deionized water. Subsequently, 750 mg sodium chloride (12.83 mmol) and 8.50 g citric acid (44.24 mmol, serving as a slow-release agent for Ti3+ ions) were added to the reaction mixture. The resulting solution was transferred to a 47 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated at 180 °C for 4 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the products were thoroughly washed with deionized water and ethanol via centrifugation followed by drying (Fig. S1).

Preparation of N-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(triethoxysilyl)propan-1-imine (SAPy)

SAPy was synthesized according to our previous method42. Typically, a solution of (3-oxopropyl)trimethoxysilane (0.8 mL, 5 mmol) in ethanol (10 mL)51 was gradually added to a solution of 4-aminopyridine (5 mmol) in ethanol (10 mL) at 60 °C under ultrasonic agitation. The reaction mixture was maintained under these conditions for further 60 min. After 24 h at room temperature, the precipitated product was filtered, washed with ethanol, and dried in a desiccator, yielding an 85% isolated product (Fig. S2).

Preparation of SAPy@TiO2

A suspension containing 1.0 g of the SAPy ligand in 10 mL ethanol was added gradually to a homogeneous suspension of TiO2 nanoparticles (1.0 g dispersed in 10 mL ethanol) followed by sonication for 2 h at 60 °C. The mixture was then refluxed for an additional 12 h. The resulting composition was isolated by centrifugation, washed with ethanol, and the precipitate was dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 8 h.

Synthesis of 5,10,15,20-Tetra(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin (TNPPH2) and Mn(TNPP)OAc

TNPPH2 was synthesized by the reaction of pyrrole and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde according to the published procedure50. Mn(III)TNPP(OAc) (MnTNPP) was synthesized after a metallization process of TNPP with Mn(OAc)2.4H2O in DMF (Fig. S3)51.

Preparation of MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2

To 1.0 g of SAPy/TiO2 dispersed in 10 mL of ethanol, was gradually added 0.5 g of MnTNPP dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol over a period of 10 min under ultrasonic agitation at 60 °C. The mixture was then subjected to reflux for an additional 12 h. The resulting product was collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol, and dried at 60 °C for 8 h.

Photocatalytic reaction procedure

The photocatalytic performance of the synthesized MnTNPP/SAPy@TiO2 was evaluated for the degradation of dyes in an aqueous solution. The photodegradation process was conducted under the illumination of a 40 W compact fluorescent lamp at room temperature (298 K). In a standard procedure, 10 mg of the photocatalyst was introduced into a 50 mL of 2 mg L−1 aqueous solution of RhB at pH 3, along with 62 μL of 25% H2O2 solution, with continuous stirring at room temperature. The reaction mixture was kept in the dark for 60 min to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Subsequently, the mixture was exposed to visible light, and 3 mL aliquots of the suspension were periodically sampled. The photocatalyst was separated from the solution via centrifugation followed by filtration. The concentration of RhB was determined by measuring the absorbance at 554 nm (λmax) using a UV–vis spectrophotometer and using calibration curve constructed by plotting absorbance values of standard RhB solutions against their known concentrations. The resulting linear regression equation was then used to determine the concentration of unknown samples based on their measured absorbance (Fig. S7A). The decoloration ratio (DC%) of RhB was calculated using Eq. 2.

where C0 (mg/L) and Ct (mg/L) are the initial and final RhB concentrations, respectively. The same procedure was conducted for methyl orange at a wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) of 504 nm.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Abatan, A. et al. Integrated simulation frameworks for assessing the environmental impact of chemical pollutants in aquatic systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 5, 543–554. https://doi.org/10.51594/estj.v5i2.831 (2024).

Hofstetter, T. B. et al. Perspectives of compound-specific isotope analysis of organic contaminants for assessing environmental fate and managing chemical pollution. Nat. Water 2, 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00176-4 (2024).

Periyasamy, A. P. Recent advances in the remediation of textile-dye-containing wastewater: Prioritizing human health and sustainable wastewater treatment. Sustainability 16, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020495 (2024).

Khan, Q. et al. Advanced oxidation/reduction processes (AO/RPs) for wastewater treatment, current challenges, and future perspectives: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 1863–1889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31181-5 (2024).

Imai, K. et al. Visible-light responsive TiO2 for the complete photocatalytic decomposition of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and its efficient acceleration by thermal energy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 346, 123745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.123745 (2024).

Nesterov, D. et al. Approaching the circular economy: Biological, physicochemical, and electrochemical methods to valorize agro-industrial residues, wastewater, and industrial wastes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.113335 (2024).

Rodrigues, F. et al. Efficacy of bacterial cellulose hydrogel in microfiber removal from contaminated waters: A sustainable approach to wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 919, 170846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170846 (2024).

Ponnusami, A. B. et al. Advanced oxidation process (AOP) combined biological process for wastewater treatment: A review on advancements, feasibility and practicability of combined techniques. Environ. Res. 237, 116944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116944 (2023).

Iqbal, A. et al. Emerging developments in polymeric nanocomposite membrane-based filtration for water purification: A concise overview of toxic metal removal. Chem. Eng. J. 481, 148760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.148760 (2024).

Belzile, N. & Chen, Y.-W. Re-utilization of drinking water treatment residuals (DWTR): A review focused on the adsorption of inorganic and organic contaminants in wastewater and soil. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 10, 1019–1033. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EW00927K (2024).

Zaharia, C., Musteret, C.-P. & Afrasinei, M.-A. The use of coagulation-flocculation for industrial colored wastewater treatment—(I) the application of hybrid materials. Appl. Sci. 14, 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14052184 (2024).

Mohtaram, S. et al. Enhancement strategies in CO2 conversion and management of biochar supported photocatalyst for effective generation of renewable and sustainable solar energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 300, 117987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117987 (2024).

Morshedy, A. S. et al. A review on heterogeneous photocatalytic materials: Mechanism, perspectives, and environmental and energy sustainability applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 163, 112307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112307 (2024).

Hussain, R. T., Hossain, M. S. & Shariffuddin, J. H. Green synthesis and photocatalytic insights: A review of zinc oxide nanoparticles in wastewater treatment. Mater. Today Sustain. 26, 100764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100764 (2024).

Hamrayev, H., Korpayev, S. & Shameli, K. Advances in synthesis techniques and environmental applications of TiO2 nanoparticles for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Res. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 12, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.37934/jrnn.12.1.124 (2024).

Khizer, M. R. et al. Polymer and graphitic carbon nitride based nanohybrids for the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment—A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 350, 127768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127768 (2024).

Kumari, S. et al. Zeolites in wastewater treatment: A comprehensive review on scientometric analysis, adsorption mechanisms, and future prospects. Environ. Res. 260, 119782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119782 (2024).

Motshekga, S. C., Oyewo, O. A. & Makgato, S. S. Recent and prospects of synthesis and application of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in water treatment: A review. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 34, 3907–3930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-024-03063-x (2024).

Jabbar, Z. H. et al. A critical review describes wastewater photocatalytic detoxification over Bi5O7I-based heterojunction photocatalysts: characterizations, mechanism insight, and DFT calculations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.112241 (2024).

Ikram, Z., Azmat, E. & Perviaz, M. Degradation efficiency of organic dyes on CQDs as photocatalysts: A review. ACS Omega 9, 10017–10029. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c09547 (2024).

Ishaq, T., Kanwal, A. & Sattar, R. Recent developments in fullerene-based materials for photocatalytic applications in wastewater treatment and water splitting. ChemistrySelect 9, e202401561. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202401561 (2024).

Avornyo, A. & Chrysikopoulos, C. V. Applications of graphene oxide (GO) in oily wastewater treatment: Recent developments, challenges, and opportunities. J. Environ. Manag. 353, 120178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120178 (2024).

Shabil Sha, M. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using reduced graphene oxide (RGO). Sci. Rep. 14, 3608. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53626-8 (2024).

Shee, N. K. & Kim, H.-J. Porphyrin-based nanomaterials for the photocatalytic remediation of wastewater: Recent advances and perspectives. Molecules 29, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29030611 (2024).

Mao, T. et al. Research progress of TiO2 modification and photodegradation of organic pollutants. Inorganics 12, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics12070178 (2024).

Silvestri, S., Fajardo, A. R. & Iglesias, B. A. Supported porphyrins for the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in water: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 731–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01344-2 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. The visible light degradation activity and the photocatalytic mechanism of tetra(4-Carboxyphenyl) porphyrin sensitized TiO2. Mater. Res. Bull. 57, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.06.017 (2014).

Zhu, H.-C., Zhang, J. & Wang, Y.-L. Adsorption orientation effects of porphyrin dyes on the performance of DSSC: Comparison of benzoic acid and tropolone anchoring groups binding onto the TiO2 anatase (101) surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 433, 1137–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.10.087 (2018).

Duan, M. et al. Pt(II) porphyrin modified TiO2 composites as photocatalysts for efficient 4-NP degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 5499–5504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.02.069 (2012).

Chang, M.-Y. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol wastewater using porphyrin/TiO2 complexes activated by visible light. Thin Solid Films 517, 3888–3891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2009.01.175 (2009).

Granados-Oliveros, G. et al. Degradation of atrazine using metalloporphyrins supported on TiO2 under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 89, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.01.001 (2009).

Huang, C. et al. Visible photocatalytic activity and photoelectrochemical behavior of TiO2 nanoparticles modified with metal porphyrins containing hydroxyl group. Ceram. Int. 40, 7093–7098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.12.042 (2014).

Huang, H. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B on TiO2 nanoparticles modified with porphyrin and iron-porphyrin. Catal. Commun. 11, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2009.08.012 (2009).

de Oliveira, C. P. M. et al. High surface area TiO2 nanoparticles: Impact of carboxylporphyrin sensitizers in the photocatalytic activity. Surf. Interfaces 21, 100774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100774 (2020).

Ahmed, M. A. et al. Effect of porphyrin on photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles toward Rhodamine B photodegradation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 176, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.09.016 (2017).

Tasseroul, L. et al. Degradation of p-nitrophenol and bacteria with TiO2 xerogels sensitized in situ with tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrins. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 272, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.08.023 (2013).

Murphy, S. et al. Photocatalytic activity of a porphyrin/TiO2 composite in the degradation of pharmaceuticals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 119, 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.02.027 (2012).

Rahimi, R., Saadati, S. & Honarvar Fard, E. Fluorine-doped TiO2 nanoparticles sensitized by tetra(4-Carboxyphenyl) porphyrin and zinc tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin: preparation, characterization, and evaluation of photocatalytic activity. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 34, 1341–1348. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.12124 (2015).

Sun, W. et al. Surface-modification of TiO2 with new metalloporphyrins and their photocatalytic activity in the degradation of 4-nitrophenol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 940–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.09.032 (2011).

Kar, P. et al. Impact of metal ions in porphyrin-based applied materials for visible-light photocatalysis: Key information from ultrafast electronic spectroscopy. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 10475–10483. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201402632 (2014).

Hart, A. S. et al. Porphyrin-sensitized solar cells: Effect of carboxyl anchor group orientation on the cell performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 5314–5323. https://doi.org/10.1021/am401201q (2013).

Keikha, N., Rezaeifard, A. & Jafarpour, M. Heterogeneous fenton-like activity of novel metallosalophen magnetic nanocomposites: Significant anchoring group effect. RSC Adv. 9, 32966–32976. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA05097C (2019).

Rezaeifard, A. et al. Enhanced visible-light-induced photocatalytic activity in M(III) salophen-decorated TiO2 nanoparticles for heterogeneous degradation of organic dyes. ACS Omega 8, 3821–3834. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c05971 (2023).

Negre, C. F. A. et al. Efficiency of interfacial electron transfer from zn-porphyrin dyes into TiO2 correlated to the linker single molecule conductance. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 24462–24470. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp408738b (2013).

Li, G. et al. Synergistic effect between anatase and rutile TiO2 nanoparticles in dye-sensitized solar cells. Dalt. Trans. https://doi.org/10.1039/B908686B (2009).

Jafarpour, M. et al. Tandem photocatalysis protocol for hydrogen generation/olefin hydrogenation using Pd-g-C3N4-Imine/TiO2 nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 60, 9484–9495. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c00603 (2021).

Saha, T. K. et al. Efficient oxidative degradation of azo dyes by a water-soluble manganese porphyrin catalyst. ChemCatChem 5, 796–805. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201200475 (2013).

Ruan, C. et al. Synthesis of porphyrin sensitized TiO2/graphene and its photocatalytic property under visible light. Mater. Lett. 141, 362–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2014.11.095 (2015).

Jafarpour, M. et al. Starch-coated maghemite nanoparticles functionalized by a novel cobalt schiff base complex catalyzes selective aerobic benzylic C-H oxidation. RSC Adv. 5, 38460–38469. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA04718H (2015).

Zhang, W. et al. Directing two azo-bridged covalent metalloporphyrinic polymers as highly efficient catalysts for selective oxidation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 489, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2014.10.023 (2015).

Feng, Z. et al. catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane to KA oil by zinc oxide supported manganese 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-Nitrophenyl) porphyrin. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 410, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2015.09.027 (2015).

Rochford, J., Chu, D., Hagfeldt, A. & Galoppini, E. Tetrachelate porphyrin chromophores for metal oxide semiconductor sensitization: Effect of the spacer length and anchoring group position. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4655–4665. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja068218u (2007).

Milana, P. et al. Effect of anchoring groups on electron transfer at porphyrins-TiO2 interfaces in dye-sensitized solar cell application. Macromol. Symp. 391, 1900126. https://doi.org/10.1002/masy.201900126 (2020).

Shee, N. K. & Kim, H.-J. Two-dimensional porous porphyrin materials composed of robust Tin(IV)-porphyrin linkages for photocatalytic wastewater remediation. Dalt. Trans. 54, 2448–2459. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4DT03277B (2025).

Rahimi, R. et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin and zinc derivative and study of their bacterial photoinactivation. Iran. Chem. Commun. 4, 175–185 (2016).

Vasconcelos, D. C. L. et al. Infrared Spectroscopy of titania sol-gel coatings on 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2, 1375–1382. https://doi.org/10.4236/msa.2011.210186 (2011).

Cychosz, K. A. et al. Recent advances in the textural characterization of hierarchically structured nanoporous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CS00391E (2017).

Praveen, P. et al. Structural, optical and morphological analyses of pristine titanium di-oxide nanoparticles—Synthesized via sol-gel route. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 117, 622–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2013.09.037 (2014).

Milanesi, L. et al. Binding of a Co(III) metalloporphyrin to amines in water: influence of the pKa and aromaticity of the ligand, and ph-modulated allosteric effect. Inorg. Chem. 64, 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c04183 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Photodegradation of surfactants. 11. zeta-potential measurements in the photocatalytic oxidation of surfactants in aqueous titania dispersions. Langmuir 9, 1646–1650. https://doi.org/10.1021/la00031a008 (1993).

Liu, S. et al. Coupling graphitic carbon nitrides with tetracarboxyphenyl porphyrin molecules through π–π stacking for efficient photocatalysis. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 10677–10688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-03617-y (2020).

Shee, N. K. & Kim, H.-J. Sn(IV) porphyrin-anchored TiO2 nanoparticles via axial-ligand coordination for enhancement of visible light-activated photocatalytic degradation. Inorganics 11, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics11080336 (2023).

Hacıefendioğlu, D. et al. A porphyrinic, titanium-based metal organic framework as a superior photocatalyst for visible light driven dye degradation. Surfaces Interfaces 58, 105778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2025.105778 (2025).

Watanabe, T., Takizawa, T. & Honda, K. Photocatalysis through excitation of adsorbates. 1. highly efficient N-deethylation of rhodamine B adsorbed to cadmium sulfide. J. Phys. Chem. 81, 1845–1851. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100534a012 (1977).

Fan, Y. et al. Highly selective deethylation of rhodamine B on TiO2 prepared in supercritical fluids. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 173865. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/173865 (2012).

Singh, K. et al. Effect of the standardized ZnO/ZnO-GO filter element substrate driven advanced oxidation process on textile industry effluent stream. ACS Omega 8, 28615–28627. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c03122 (2023).

Groeneveld, I. et al. Parameters that affect the photodegradation of dyes and pigments in solution and on substrate—An overview. Dyes Pigm. 210, 110999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110999 (2023).

Devi, L. G. et al. Photodegradation of methyl orange by advanced fenton process using zero valent iron: Parameters and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 164, 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.017 (2009).

Kobaisy, A. M. et al. Surface-decorated porphyrinic zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks for photodegradation of methyl orange dye. RSC Adv. 13, 23050–23060. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA02656F (2023).

Shao, L. et al. Preparation of a novel nanofibrous mat-supported Fe(III) porphyrin/TiO2 photocatalyst and its application in photodegradation of azo-dyes. Environ. Eng. Sci. 29, 807–813. https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2011.0260 (2012).

Brunmark, A. & Cadenas, E. Electronically excited state generation during the reaction of p-benzoquinone with H2O2: Relation to product formation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 3, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(87)90002-5 (1987).

Shi, T.-S., Sun, H.-R., Cao, X.-Z. & Tao, J.-Z. Spectroelectrochemical characteristics of tetrakis (4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin manganese complex. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. Ed. 15, 969 (1994).

Dance, I. The correlation of redox potential, HOMO energy, and oxidation state in metal sulfide clusters and its application to determine the redox level of the FeMo-Co active-site cluster of nitrogenase. Inorg. Chem. 45, 5084–5091 (2006).

Rezaeifard, A., Mokhtari, R., Garazhian, Z., Jafarpour, M. & Grzhegorzhevskii, K. V. Tetrahedral keggin core tunes the visible light-assisted catalase-like activity of icosahedral keplerate shell. Inorg. Chem. 61, 7878–7889 (2022).

Babu, V. J., Vempati, S., Uyar, T. & Ramakrishna, S. Review of one-dimensional and two-dimensional nanostructured materials for hydrogen generation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 2960–2986 (2015).

Liu, T. et al. Comparative study of the photocatalytic performance for the degradation of different dyes by ZnIn2S4: Adsorption, active species, and pathways. RSC Adv. 7, 12292–12300. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA00199A (2017).

Kgatle, M. et al. Degradation kinetics of methyl orange dye in water using trimetallic Fe/Cu/Ag nanoparticles. Catalysts 11, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11040428 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Study on the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in water using Ag/ZnO as catalyst. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 19, 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasms.2008.03.008 (2008).

Sun, X. et al. Efficient degradation of methyl orange in water via both radical and non-radical pathways using Fe–Co bimetal-doped MCM-41. Chem. Eng. J. 402, 125881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.125881 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Support of this work by research Council of University of Birjand is appreciated. We sincerely thank Prof. D. Nematollahi and Dr. M. Ahmadi from the Department of Analytical Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry and Petroleum Sciences at Bu-Ali Sina University, for their kind and collaborative support. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of S. Shariatinia, PhD student at Bu-Ali Sina University, and R. Akbari, PhD student at the University of Birjand, for their valuable assistance in performing some reactions and analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. R.: Synthesis of catalyst, experiments and methodology, Writing the original draft; A.R.: Corresponding author, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing, and editing of the manuscript; M. J.: Supervision of organic synthesis, editing of the final draft; A. Z. M.: Supervision of methodology, editing of the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezaei, M., Rezaeifard, A., Jafarpour, M. et al. Manganese (III) meso-tetrakis(4-nitrophenyl) porphyrin sensitizes TiO₂ nanoparticles into visible region via a pyridyl linker for degradation of organic dyes. Sci Rep 15, 43906 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27792-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27792-2