Abstract

Metals are required by all life to build metalloproteins, but the metal preferences of the dominant microbes have evolved over geological time. Consistent with this, experiments and models predict that metal availability in anoxic seawater during the Archean and Proterozoic eons (4.0–0.541 billion years ago) would have been radically different to today. Corroborating this in the geological record is challenging because bulk rock geochemistry reflects complex histories. Here we take a novel approach, determining the transition metal content of micron-scale laths of greenalite, a primary Fe(II)-silicate mineral, from the Kuruman Formation of the Transvaal Supergroup, South Africa. Our data provide a high-resolution snapshot of seawater chemistry ~ 2.46 Ga, and reveal striking compositional differences compared to today: Zn and V were relatively scarce, Ni was similar, Co was enriched, and Mn was highly-enriched. Our data are largely consistent with chemical predictions and overlap with constraints from a range of different geological archives. Ancient seawater was therefore dominated by Fe and Mn, consistent with evidence that early life preferentially utilised these transition metals. Extremely high Mn concentrations could have interfered with cellular homeostasis, as well as disrupting DNA synthesis, potentially driving faster rates of evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Experimental data, thermodynamic models, and proteomics all suggest that the bioavailability of various transition metals in seawater has changed dramatically over geological time1,2,3,4,5. These changes have been interpreted to reflect major geological events, such as the cooling of the mantle and the emergence of stable subaerial continents, as well as biological and chemical changes in seawater. In the Archean and Proterozoic eons, the oceans were dominantly anoxic and rich in iron (Fe2+), which could have resulted in complexation, sorption, and co-precipitation of metals onto Fe(II)-bearing phases, Fe(III)-bearing phases, or iron sulphide minerals1,5,6. Early thermodynamic models of transition metal availability were based on interactions with free-sulfide1,2, but current geochemical data indicate that sulfidic conditions were spatially limited, and instead point towards an early ocean that was rich in dissolved Fe2+ (ferruginous) and dissolved silica7,8,9. Under these conditions, models and experiments suggest that abundant greenalite precipitation around hydrothermal vent systems and on the shelf would have removed certain transition metals from seawater, exerting a different control on transition metal availability compared to the modern ocean5,10. If greenalite was a dominant control on transition metal availability, then we predict that Zn and V would be scarce, Co and Ni would be partially depleted, and Mn would have been abundant5,10.

Attempts to corroborate model predictions using data from the rock record have focussed on changes in the average abundance of a particular metal in either shales, pyrite, or iron formation over long timespans6,11,12,13,14,15. While these records present a broad overview of large shifts, they are limited by several factors. Firstly, some of these records only provide qualitative constraints, because the crystallographic location of the metal and the partitioning behaviour during precipitation of that phase is unknown. Secondly, mobilisation of metals during diagenesis and metamorphism could modify records16. Current data from the rock record present several inconsistencies with biological and thermodynamic constraints. For example, Zn records from shales and banded iron formation suggest that Zn levels remained stable over geological time, yet thermodynamic models and proteomic data indicate that Zn availability was low in early marine systems12,17. While some older thermodynamic models are based on a now outdated assumption of widespread euxinia, and omit the greenalite sink, there are also limitations to bulk rock geochemical records.

Recently, greenalite has been proposed as an archive of early seawater chemistry. Petrographic evidence indicates that it was one of the earliest phases preserved in iron formation18, and was coated in silica and lithified in early diagenetic chert, which could have protected primary geochemical signals from diagenetic and late-stage alteration19,20. Experimental work has demonstrated that several key transition metals partition into the Fe(II)-silicate gel - thought to be a precursor to crystalline greenalite - during precipitation, and the partition coefficients are well constrained5. Furthermore, most transition metals are largely retained in the structure during simulated diagenesis, indicating that greenalite could provide a robust proxy archive5. Here, we present mineral-specific transition metal contents for natural greenalite from the ~ 2.46 Ga Kuruman Formation, Transvaal Supergroup, South Africa, and place these into a quantitative framework to calculate the concentration of five key transition metals in Palaeoproterozoic seawater from a point in geological time.

Transition metal abundance in archean greenalite

We present data for five transition metals obtained from 54 independent laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analyses across three greenalite-rich drill core samples from a 2-metre section of the Kuruman iron formation. Identifying greenalite within drill core samples poses a challenge due to its fine grain size and intimate association with chert. Therefore, greenalite was first identified in three samples using bulk rock X-ray spectroscopic techniques, then prepared by cutting parallel to laminae to expose a single surface, followed by mineralogical verification via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) (see Supplementary Sect. 1). Each laminae was analysed multiple times at different locations using LA-ICP-MS21, with a spot size of 120 μm. Each analysis encompassed varying proportions of greenalite laths (< 1 μm wide and ~ 2–7 μm long) embedded in chert cement (Fig. 1; Table 1). Although this results in a smaller dataset compared to conventional bulk LA-ICP-MS studies, the dataset is of higher specificity and interpretive power, as it focuses exclusively on greenalite and avoids the mineralogical averaging inherent in bulk-rock analyses. The approach is significantly more labour-intensive, requiring integration of multiple imaging, analytical, and computational workflows for each data point.

A–H: Cross plots of unadjusted metal abundances in Palaeoproterozoic greenalite from three samples in this study vs. the %greenalite which was estimated via SEM. 349–59 A and B (diamonds and squares) contained only chert and greenalite, whereas 351 − 66 contained greenalite, chert, and minor siderite (crosses).

To determine which metals were hosted in greenalite, we examined bivariate relationships between metal concentrations and the proportion of greenalite in each ablation crater. Strong linear correlations between Co, V, Zn, Mn, and Ni concentrations and greenalite abundance in samples 349–59 A and 349-59B indicate that these metals are primarily hosted in greenalite rather than chert (Fig. 1). This interpretation is supported by experimental evidence showing that these elements are structurally incorporated into Fe(II)-silicate precursor gels and retained during recrystallization to greenalite5. In contrast, Cd, Cu, and Mo showed no such correlation, implying they are not incorporated into the greenalite structure and are instead associated with surface-bound or chert-related phases. Consequently, only the five metals (Co, V, Zn, Mn, and Ni) that are demonstrably greenalite-hosted were used to reconstruct Palaeoproterozoic seawater concentrations.

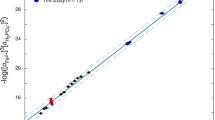

Following ablation, each crater was individually imaged using SEM-EDS, and trace metal data were corrected for chert dilution using a custom MATLAB script (see Supplementary Sect. 2). To avoid siderite-related metal contributions, only corrected data from the two samples lacking siderite (see Supplementary Sect. 3) were used for seawater reconstruction. We used experimentally determined partition coefficients for each metal5 to convert the metal-to-iron ratio in natural greenalite into an estimate of the metal-to-iron ratio in the precipitating fluid (Nke et al., 2024; see Online Methods Sect. 5) (Fig. 2). The partition coefficients were determined over the full pH range that supports greenalite precipitation and over a wide range of H4SiO4(aq) concentrations. Solubility constraints derived from greenalite and siderite stability, along with kinetic experiments, suggest that Fe2+ concentrations in Archean seawater ranged between 0.1 and 1 mmol.kg− 1(ref. 22,23,24), and we take 0.1 mmolKg− 1 for the following calculations in Fig. 2 (note this results in higher concentrations for all metals compared to an Fe2+ of 1 mmolKg− 1). Our results suggest that Zn and V concentrations were substantially lower than those in modern seawater by 3 to 4 orders of magnitude, while Ni levels were comparable. In contrast, Co and Mn concentrations were markedly elevated, exceeding modern values by 3 to 6 orders of magnitude (Table 1; Fig. 2B).

We compared our trace metal concentrations to published data from greenalite-chert samples in the 2.48–2.46 Ga Brockman Iron Formation, Western Australia, reported by Muhling et al. (2023)25, as well as from greenalite-rich horizons in the Kuruman Formation of the Transvaal Supergroup reported by Oonk et al. (2018)26. Craters labelled “this study–Greenalite” in Fig. 3 contained > 50% greenalite (see Supplementary Sect. 2), while those labelled “this-study–Chert” contained 5–20% greenalite, with similar Fe contents to those reported by Muhling et al. (2023) (5–28 wt%). Notably, V, Zn, Mo, Co, Ni, and Mn are markedly higher in our greenalite-rich samples than in those from Muhling et al., which instead closely resemble our chert-rich analyses (Fig. 3). In contrast, Cu and Cd show no correlation with greenalite abundance across our crater analyses, and are consistently low in greenalite-rich samples but elevated in chert-rich samples, including those reported by Muhling et al. These observations support our interpretation that Cu and Cd are not structurally incorporated into greenalite and are instead predominantly associated with the chert phase. The higher Ni and Mn reported in Oonk et al., (2018), relative to Muhling et al., 2023, could be due to minor siderite contamination.

A: Transition metal concentrations in Palaeoproterozoic greenalite, corrected for chert dilution, with corresponding partition coefficients (K′D) for each metal, based on ref5.. Metal concentrations are displayed in mol.kg− 1, adjusted to 100% greenalite, with a median line indicating central values. B: Calculated transition metal concentration in Palaeoproterozoic seawater from this study, assuming an Fe2+ concentration of 0.1 mmol.kg− 1(ref. 23). Estimates of seawater concentrations of Fe23 and Mg46at this time are shown for comparison. Solid boxes show range of reported key metal concentrations for modern seawater, including V (ref. 56), Zn (ref. 38), Co (ref. 57), Ni (ref. 58), Mn (ref. 38), Fe (ref. 59), and Mg (ref. 60).

An archive of shallow marine conditions

Our data reflect transition metal abundance in the local environment during the precipitation of primary greenalite, which raises the question, where did these minerals form? Several potential pathways have been proposed for greenalite formation, including around hydrothermal vents5,10,27, followed by lateral transport and deposition in a shelf setting, or direct deposition from seawater driven by warmer temperatures, pH increases or low levels of Fe3+ (ref. 28,29), as well as diagenetically30. We analysed rare earth element patterns from the same ablation craters as those which were analysed for the metal data, and the patterns are similar to those of penecontemporaneous carbonate rocks and contain many of the key features of a typical seawater signature21. While greenalite may have been an abundant precipitate at hydrothermal vents, and is preserved in some exhalative deposits27, the greenalite preserved within iron formation in the Transvaal Supergroup, South Africa represents an archive of ambient seawater in a shelf setting, where most ecosystems are located. Although our dataset is modest in size, the analytical approach employed prioritises specificity, quality, and interpretive clarity over quantity. Rather than analyzing bulk samples that average across mineral phases and alteration domains, we focused on in-situ greenalite, validated through multiple independent techniques and corrected for host matrix effects. While this necessitates a smaller number of analyses, it enhances confidence in the fidelity of our seawater metal reconstructions. As such, our results should be viewed as a targeted, high-resolution snapshot of Palaeoproterozoic seawater chemistry, not a global average, but one that nonetheless reveals substantial elemental deviations from the modern ocean.

A consistent picture from multiple archives

Bulk rock records utilise large datasets spanning billions of years and integrate spatial and temporal variability. Shale records have the advantage that they can be calibrated against modern sediments, but potential variation in the partition coefficient with other parameters (e.g. pH, sedimentation rate, SiO2) is poorly constrained, and a local hydrothermal source, later hydrothermal enrichment, contamination in laboratory environments (especially of Zn), or incorporation of other phases during dissolution could all skew the published shale and hematite records towards higher values31. Hematite records are tied to experimental constraints on partitioning behaviour, but recent work has shown that at least some of the natural hematite in the rock record is a product of late-stage oxidation making the chemical composition difficult to interpret32. Nevertheless, it can be illuminating to compare with existing trace metal records to identify areas of agreement.

Our estimates for the concentration of Ni, Co, and V are consistent with some independent estimates from other archives13,14,33,34. For example, long term records of Ni/Fe ratios in hematite and magnetite, which assume ferrihydrite was the primary precursor mineral, suggest dissolved Ni concentrations were high in the Archean, reaching hundreds of nmol.kg− 1, but dropped dramatically around the Archean–Palaeoproterozoic boundary33. Our data suggest that Ni concentrations in the Early Palaeoproterozoic Era (4–7 nmol.kg− 1) were moderately higher than those in modern seawater, and this overlaps with the lower end of the range of estimates from bulk iron formation from the Transvaal Supergroup, which constrain Ni concentrations to 2.3–146 nmol.kg− 1 (at SiO2(aq) = 0.67 mmol.kg− 1; ref33.) (Fig. 4). Our data indicate that Co concentrations were considerably higher in the Early Palaeoproterozoic Era (0.2–0.7 nmol.kg− 1) compared to the present day, and this is also consistent with available geological data. Co/Ti and Co/Al ratios in Late Archean pyrite, iron formation, and shales are all elevated compared to modern sediments, and this is qualitatively interpreted to indicate higher concentrations in seawater13. While greenalite precipitation may have removed modest amounts of Ni and Co, we suggest that this was not sufficient to compensate for the increased flux from alteration of abundant Ni- and Co-rich ultramafic rocks.

In contrast, our data suggest that V was scarce in Early Palaeoproterozoic seawater (0.2–1 pmol.kg− 1), with a concentration four orders of magnitude lower than today. Consistent with this, black shale pyrite and bulk iron formation records both show an increase in V content in later parts of the Proterozoic Eon, interpreted to reflect increased continental weathering inputs as conditions became more oxidising14,34, and this is also reflected in increasing preservation of V(V)-bearing minerals over time35. Vanadium levels may have been supressed by pervasive sinks under anoxic, ferruginous conditions, including scavenging by clay minerals and co-precipitation with Fe(II)-silicate minerals.

Our data indicate that Zn concentrations in the Palaeoproterozoic Era (1–1.2 pmol.kg− 1) were three orders of magnitude lower than in modern seawater (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with mineral precipitation experiments that show greenalite precipitation around vent systems could have stripped Zn from hydrothermal fluids, drastically limiting the input flux5. The Zn content of pyrite minerals also supports a depleted Zn reservoir in the Archean14. However, a significant discrepancy arises between our data and the Zn record from shales and hematite12,17, which both show a large range of Zn content, but with no trend in the range or average over geological time. These records have been used to infer that the marine Zn reservoir has remained stable at concentrations close to 10 nmol.kg− 1 since the Archean. Zn is particularly vulnerable to contamination in laboratory settings, and it is likely that different metals have varying resilience to recrystallisation or alteration with late-stage fluids. While the greenalite record circumvents many of the limitations of bulk rock records, it is limited to one point in geological time and may capture a Zn-depleted micro-environment that is not representative of the long-term seawater average.

Manganese was a major component of early seawater

The greenalite data indicate that Mn was abundant in Palaeoproterozoic seawater, more so than any other transition metal (Fig. 2). In the modern ocean, Mn is a trace element with a concentration of up to 4 nanomol.kg− 1(ref. 38), yet our data imply concentrations reached 7 millimol.kg− 1 in the Palaeoproterozoic Era, making Mn a major component of early seawater. While our data provide a snapshot of conditions from one location, such high concentrations would imply long residence times, and so Mn concentrations would have likely been conservative across the ocean.

Quantitative estimates of Mn concentrations in the past oceans are limited to thermodynamic modelling, which suggests Mn concentrations were high (up to 0.1 mmol.kg− 1), although those studies focussed on the impact of dissolved sulfide1,16 (Fig. 4). However, the relatively high Mn concentrations observed in greenalite contrast with the low Mn typically reported in bulk IF datasets36,37. This discrepancy likely reflects several factors: (1) greenalite is often a minor phase in many IFs, (2) bulk datasets are biased toward greenalite-poor, ore-grade facies due to selective sampling, and (3) greenalite commonly alters to magnetite or hematite during late-stage fluid interaction, which can reset or erase original trace element signatures. Thus, preserved greenalite may retain a more primary seawater metal signal than bulk IF averages, particularly for redox-sensitive elements like Mn.

The high concentrations of Mn derived from the greenalite archive are consistent with our understanding of the early Mn cycle. Rock weathering provides a substantial flux of Mn2+ to Earth surface environments, as do hydrothermal systems. On the early Earth, hydrothermal fluxes were considerably higher than today, due to higher mantle heat fluxes39, and further, hydrothermal fluids are predicted to have been enriched in reducing elements under anoxic conditions. For example, the concentration of Fe in hydrothermal fluids is estimated to have been up to 10–100 mmol.kg− 1(ref. 40). The chemistry of hydrothermal fluids in the Palaeoproterozoic Era may have been different, but using an Fe/Mn ratio of 10, similar to modern systems41, indicates Mn concentrations were 1–10 mmol.kg− 1. Removal fluxes of Mn would have been less pervasive in early seawater, as Mn(IV) oxide minerals do not form under anoxic conditions, except via sluggish light driven reactions42. Manganese removal would instead have been controlled by the solubility of Mn(II)-carbonate or Mn(II)-silicate minerals, or removal as a trace constituent of carbonates. Our data indicate that the critical supersaturation required to nucleate these phases must have placed a high ceiling on dissolved Mn2+.

Manganese-rich oceans are supported by widespread, thick deposits of Mn-bearing sediments in the Archean Eon and Palaeoproterozoic Era43,44, as well as elevated Mn-content in early carbonate rocks45. If Mn concentrations were high in the earliest Palaeoproterozoic, immediately prior to atmospheric oxidation, this implies that Mn was also high throughout the preceding Archean Eon, when conditions were persistently anoxic. Our work demonstrates the utility of greenalite as a proxy archive, and this approach could be used to explore a range of metal concentrations, and their isotopes, in different environmental settings over geological time.

Manganese as a mutagen and evolutionary accelerant

The emergence and evolution of early microbial life would have been strongly influenced by the chemistry of contemporaneous seawater. The majority of early metalloproteins are thought to have been cambialistic, meaning microbes were able to adapt to use whichever metals were environmentally abundant4. Previous work has highlighted the role of abundant Mg2+ (20–50 mmol.kg− 1)46 and Fe2+ (0.1–1 mmol.kg− 1)23 in early seawater; here we propose that Mn2+ was at similarly high concentrations (3.3–7.6 mmol.kg− 1). Together with major elements Na+ and Ca2+, these three cations would have swamped ocean cation chemistry16. This fits with a wealth of evidence from proteomic and phylogenomic data, which indicate higher utilisation of these metals in early evolving metabolisms4,47. In particular, abundant Mn2+ provided an opportunity for the development of the water splitting centre in photosystem II, which enabled high potential photosynthesis48. In contrast, the utilisation of metals such as Zn, Ni, Co, and V would have demanded the development of highly specialised machinery, depriving microbes of opportunities to experience their unique chemical properties and the potential evolutionary avenues that they could unlock.

In a chemical world dominated by five cations (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+), the dynamics among them would have been determined by the stability constants for binding between metals and biological chelators, following the Irving-Williams order. For example, iron enzymes play a diverse and vital role in cellular processes such as respiration and photosynthesis, and are thought to have been the most common metallo-catalysts in early evolution49. Despite Mn concentrations comparable to or even higher than Fe, Mn is unlikely to have interfered with cellular Fe uptake because the binding affinity by chelators for Mn is lower than for Fe. In contrast, the binding affinity for Mn is considerably higher than for Mg, and so if concentrations were comparable (our data indicate Mn/Mg ratio of between 0.07 and 0.38), Mn could have interfered with Mg uptake50.

Magnesium is a central component of all cells due to its role as cellular homeostasis. It is the mobility of Mg within organic cells, driven by its low binding affinity, that underpins its success as a regulator of numerous cell functions and enzymes. While Mn can substitute for Mg in many cellular roles51,52,53, it would perform poorly, slowing down cellular regulation and reducing the ability of cells to quickly respond to external stimuli. Mg2+ is also used to activate DNA polymerase, the enzyme that synthesizes DNA molecules, where it is central to both catalysis of the nucleotidyl transfer reaction and the base excision. Mn2+ can substitute for Mg2+ at the metal site, but because Mn2+ is more polarisable, this leads to increased errors in newly synthesised DNA51,54. The frequency of aminopurine misinsertions increases from 6.3% in the presence of Mg2+ to 29.2% in the presence of Mn2+(ref. 54). Mn2+ also binds more tightly to the carboxylate groups and the triphosphate moiety of dNTPs compared to Mg2+, reducing base selectivity. In the Mn-rich oceans of the early Earth, Mn substitution would have had mutagenic effects on cells16. While moderate increases in mutation rates can favour evolutionary rescue, increasing the probability that a population can respond to stress, beyond some critical threshold, the accumulation of a large mutation load can lead to extinction55. While a Mn-rich environment would have posed a challenge to early microbial life, one potential side effect would have been more rapid rates of evolution, which could be consistent with a period of rapid innovation and genetic expansion in the Archean16,47.

Data availability

Raw data that support the findings of this study have been uploaded as a supplementary datafile.

References

Saito, M. A., Sigman, D. M. & Morel, F. M. M. The bioinorganic chemistry of the ancient ocean: the co-evolution of cyanobacterial metal requirements and biogeochemical cycles at the Archean–Proterozoic boundary? Inorg. Chim. Acta. 356, 308–318 (2003).

Williams, R. J. P. Fraústo Da silva, J. J. R. Evolution was chemically constrained. J. Theor. Biol. 220, 323–343 (2003).

Dupont, C. L., Yang, S., Palenik, B. & Bourne, P. E. Modern proteomes contain putative imprints of ancient shifts in trace metal geochemistry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 17822–17827 (2006).

Dupont, C. L., Butcher, A., Valas, R. E. & Bourne, P. E. & Caetano-Anollés, G. History of biological metal utilization inferred through phylogenomic analysis of protein structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 10567–10572 (2010).

Tostevin, R. & Ahmed, I. A. M. Micronutrient availability in precambrian oceans controlled by greenalite formation. Nat. Geosci. 16, 1188–1193 (2023).

Konhauser, K. O. et al. Phytoplankton contributions to the trace-element composition of precambrian banded iron formations. GSA Bull. 130, 941–951 (2017).

Poulton, S. W. & Canfield, D. E. Ferruginous conditions: A dominant feature of the ocean through earth’s history. Elements 7, 107–112 (2011).

Maliva, R. G., Knoll, A. H. & Simonson, B. M. Secular change in the precambrian silica cycle: insights from Chert petrology. GSA Bull. 117, 835–845 (2005).

Siever, R. The silica cycle in the precambrian. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 56, 3265–3272 (1992).

Tosca, N. J. & Tutolo, B. M. Hydrothermal vent fluid-seawater mixing and the origins of archean iron formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 352, 51–68 (2023).

Anbar, A. D. & Knoll, A. H. Proterozoic ocean chemistry and evolution: A bioinorganic bridge? Science 297, 1137–1142 (2002).

Scott, C. et al. Bioavailability of zinc in marine systems through time. Nat. Geosci. 6, 125–128 (2013).

Swanner, E. D. et al. Cobalt and marine redox evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 390, 253–263 (2014).

Large, R. R. et al. Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean–atmosphere evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 389, 209–220 (2014).

Robbins, L. J. et al. Trace elements at the intersection of marine biological and geochemical evolution. Earth Sci. Rev. 163, 323–348 (2016).

Johnson, J. E., Present, T. M. & Valentine, J. S. Iron: Life’s primeval transition metal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2318692121 (2024).

Robbins, L. J. et al. Authigenic iron oxide proxies for marine zinc over geological time and implications for eukaryotic metallome evolution. Geobiology 11, 295–306 (2013).

Rasmussen, B., Muhling, J. R. & Krapež, B. Greenalite and its role in the genesis of early precambrian iron formations–A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 217, 103613 (2021).

Rasmussen, B. & Muhling, J. R. Development of a greenalite-silica shuttle during incursions of hydrothermal vent plumes onto neoarchean shelf, Hamersley region, Australia. Precambrian Res. 353, 106003 (2021).

Tostevin, R. & Sevgen, S. The role of Fe (II)-silicate gel in the generation of archean and paleoproterozoic Chert. Geology 52, 706–711 (2024).

Nke, A. Y., Tsikos, H., Mason, P. R., Mhlanga, X. & Tostevin, R. A seawater origin for greenalite in iron formation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 643, 118917 (2024).

Canfield, D. E., THE EARLY HISTORY OF ATMOSPHERIC & OXYGEN. Homage to Robert M. Garrels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 1–36 (2005).

Jiang, C. Z. & Tosca, N. J. Fe(II)-carbonate precipitation kinetics and the chemistry of anoxic ferruginous seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 506, 231–242 (2019).

Sevgen, S. et al. Near-equilibrium kinetics in the Fe(II)-silicate system and the significance of nanoparticle greenalite in Archaean iron formations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 395, 135–148 (2025).

Muhling, J. R., Gilbert, S. E. & Rasmussen, B. Rare Earth element and yttrium (REY) geochemistry of 3.46–2.45 Ga greenalite-bearing banded iron formations: new insights into iron deposition and ancient ocean chemistry. Chem. Geol. 641, 121789 (2023).

Oonk, P. B. H., Mason, P. R. D., Tsikos, H. & Bau, M. Fraction-specific rare Earth elements enable the reconstruction of primary seawater signatures from iron formations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 238, 102–122 (2018).

Rasmussen, B., Muhling, J. R. & Tosca, N. J. Nanoparticulate apatite and greenalite in oldest, well-preserved hydrothermal vent precipitates. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj4789 (2024).

Rasmussen, B., Muhling, J. R., Suvorova, A. & Krapež, B. Greenalite precipitation linked to the deposition of banded iron formations downslope from a late archean carbonate platform. Precambrian Res. 290, 49–62 (2017).

Hinz, I. L., Nims, C., Theuer, S., Templeton, A. S. & Johnson, J. E. Ferric iron triggers greenalite formation in simulated archean seawater. Geology 49, 905–910 (2021).

Nims, C. & Johnson, J. E. Exploring the secondary mineral products generated by microbial iron respiration in archean ocean simulations. Geobiology 20, 743–763 (2022).

Slotznick, S. P. et al. Reexamination of 2.5-Ga whiff of oxygen interval points to anoxic ocean before GOE. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj7190 (2022).

Rasmussen, B., Krapež, B. & Meier, D. B. Replacement origin for hematite in 2.5 Ga banded iron formation: evidence for postdepositional oxidation of iron-bearing minerals. Bulletin 126, 438–446 (2014).

Konhauser, K. O. et al. Oceanic nickel depletion and a methanogen famine before the great oxidation event. Nature 458, 750–753 (2009).

Aoki, S., Kabashima, C., Kato, Y., Hirata, T. & Komiya, T. Influence of contamination on banded iron formations in the Isua supracrustal belt, West greenland: Reevaluation of the eoarchean seawater compositions. Geosci. Front. 9, 1049–1072 (2018).

Moore, E. K., Hao, J., Spielman, S. J. & Yee, N. The evolving redox chemistry and bioavailability of vanadium in deep time. Geobiology 18, 127–138 (2020).

Klein, C. & Beukes, N. J. Chapter 10 Proterozoic Iron-Formations*. in Developments in Precambrian Geology (ed. Condie, K. C.) vol. 10 383–418 (Elsevier, 1992).

Bekker, A. et al. Iron formations: their origins and implications for ancient seawater chemistry. 561–628 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.00719-1

Ikhsani, I. Y., Wong, K. H., Ogawa, H. & Obata, H. Dissolved trace metals (Fe, Mn, Pb, Cd, Cu, and Zn) in the Eastern Indian ocean. Mar. Chem. 248, 104208 (2023).

Kump, L. R., Kasting, J. F. & Barley, M. E. Rise of atmospheric oxygen and the upside-down archean mantle. Geochemistry Geophys. Geosystems 2(1), 2000GC000114 (2001).

Kump, L. R. & Seyfried, W. E. Jr Hydrothermal Fe fluxes during the precambrian: effect of low oceanic sulfate concentrations and low hydrostatic pressure on the composition of black smokers. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 235, 654–662 (2005).

Lough, A. J. M. et al. Soluble iron conservation and colloidal iron dynamics in a hydrothermal plume. Chem. Geol. 511, 225–237 (2019).

Daye, M. et al. Light-driven anaerobic microbial oxidation of manganese. Nature 576, 311–314 (2019).

Mhlanga, X. R. et al. The palaeoproterozoic Hotazel BIF-Mn formation as an archive of earth’s earliest oxygenation. Earth Sci. Rev. 240, 104389 (2023).

Johnson, J. et al. (ed, E.) Manganese-oxidizing photosynthesis before the rise of cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110 11238–11243 (2013).

Fischer, W. W., Hemp, J. & Valentine, J. S. How did life survive earth’s great oxygenation? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 31, 166–178 (2016).

Halevy, I. & Bachan, A. The geologic history of seawater pH. Science 355, 1069–1071 (2017).

David, L. A. & Alm, E. J. Rapid evolutionary innovation during an Archaean genetic expansion. Nature 469, 93–96 (2011).

Fischer, W. W., Hemp, J. & Johnson, J. E. Manganese and the evolution of photosynthesis. Orig Life Evol. Biosph. 45, 351–357 (2015).

Andreini, C., Bertini, I., Cavallaro, G., Holliday, G. L. & Thornton, J. M. Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 13, 1205–1218 (2008).

Williams, R. J. P., Rickaby, R. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Evolution’s Destiny: Co-Evolving Chemistry of the Environment and Life (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2012).

Vashishtha, A. K., Wang, J. & Konigsberg, W. H. Different divalent cations alter the kinetics and fidelity of DNA Polymerases *. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 20869–20875 (2016).

Okafor, C. D. et al. Iron mediates catalysis of nucleic acid processing enzymes: support for Fe(II) as a cofactor before the great oxidation event. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 3634–3642 (2017).

Bray, M. S. et al. Multiple prebiotic metals mediate translation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 12164–12169 (2018).

Goodman, M. F., Keener, S., Guidotti, S. & Branscomb, E. W. On the enzymatic basis for mutagenesis by manganese. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 3469–3475 (1983).

Anciaux, Y., Lambert, A., Ronce, O., Roques, L. & Martin, G. Population persistence under high mutation rate: from evolutionary rescue to lethal mutagenesis. Evolution 73, 1517–1532 (2019).

Whitmore, L. M., Morton, P. L., Twining, B. S. & Shiller, A. M. Vanadium cycling in the Western Arctic ocean is influenced by shelf-basin connectivity. Mar. Chem. 216, 103701 (2019).

Bown, J. et al. The biogeochemical cycle of dissolved Cobalt in the Atlantic and the Southern ocean South off the Coast of South Africa. Mar. Chem. 126, 193–206 (2011).

Middag, R., de Baar, H. J. W., Bruland, K. W. & van Heuven, S. M. A. C. The distribution of nickel in the West-Atlantic Ocean, its relationship with phosphate and a comparison to cadmium and zinc. Front Mar. Sci 7, 1–17 (2020).

Millero, F. J., Yao, W. & Aicher, J. The speciation of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in natural waters. Mar. Chem. 50, 21–39 (1995).

Carpenter, J. H. & Manella, M. E. Magnesium to chlorinity ratios in seawater. Journal of Geophysical Research (1896–) 78, 3621–3626 (1973).) 78, 3621–3626 (1973). (1977).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Van Der Merwe and M. Waldron (UCT) and H. de Waard (Utrecht) for support with sample preparation, SEM and LA-ICP-MS. E. Skouloudaki and G. Fanourakis performed microprobe analysis. South 32 provided drill cores and the South African National Research Foundations centre of Excellence (CIMERA & GENUS) and the Biogeochemistry Research Infrastructure Platform funded this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RT and HT designed the study. AN led field work with support from XM, HT and RT. AN and PM led the analytical work with support from RT. AN, RT and RR interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript, with input from all coauthors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nke, A.Y., Rickaby, R.E.M., Tsikos, H. et al. A window into transition metal availability in early palaeoproterozoic seawater. Sci Rep 15, 44267 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27806-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27806-z