Abstract

The stereocilin (STRC) gene is a significant contributor to mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), particularly in cases of biallelic STRC deletions and copy number alterations. Although pathogenic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or small insertion-deletions (indels) have been investigated across the coding region of STRC, the pseudogene STRCP1, which shares 98% homology with the STRC gene, makes interpreting sequence data from this region challenging. To detect missing SNVs, targeted long-read sequencing was conducted using the nanopore MinION platform coupled with long-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enrichment on individuals exhibiting heterozygous STRC deletions and associated phenotypes. Sequencing results were obtained from 149 DNA samples. The median number of reads and depth of coverage were 4,088 and 2,780, respectively. The average read length of 20.76 kbp corresponded to that of a long-range PCR product, indicating precise analysis using MinION. Forty-three individuals carrying SNVs or small indels and 27 variants were identified. Thirteen were previously reported as hearing loss-causing variants and 14 were novel variants. Long-read sequencing technology enables precise detection of pathogenic variants in complex genomic regions, such as STRC, where conventional methods face challenges owing to pseudogene interference. Therefore, this approach is a valuable complement to conventional methods for resolving unresolved SNHL. This study demonstrates the utility of targeted long-read sequencing as a complementary method to short-read NGS for resolving complex regions such as STRC. The combination with long-range PCR enabled precise enrichment and improved resolution in SNV detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a common sensory deficit that affects approximately 1–2 in 1,000 births, with 50%–70% of cases attributable to genetic factors1. The primary form of inheritance is autosomal recessive, accounting for 75% of cases. The stereocilin (STRC) gene is the primary contributor to autosomal recessive SNHL, which causes mild to moderate hearing loss2. The prevalence and incidence of STRC-associated hearing loss are relatively high in all hearing loss populations globally, with an incidence of 5.4%–16.1% in populations of mixed ethnicity3,4, 6%–11.2% in Americans5, and 1.7%–2.4% in Japanese2,6,7, owing to the high carrier frequency of STRC deletion among the general population with normal hearing. STRC is located on chromosome 15q15.3 at the DFNB16 locus and is located in a large part of a repetitive complex genomic region harboring a tandem duplication that gives rise to a pseudo-STRC gene (STRCP1). Biallelic STRC deletion (two-copy loss) is a copy number variant (CNVs) that is the most common cause of SNHL attributed to CNVs. Next-generation sequencing (NGS), followed by in silico analysis, can detect CNVs and determine whether deletion of STRC occurred, even if only short-read sequencing data are used8.

Pathogenic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or small insertion-deletions (indels) have also been investigated across the entire coding region of STRC; however, the interpretation of sequence data of the STRC region is challenging because of the pseudogene STRCP1, which has 98% homology to functional STRC. With the current NGS analysis via short-read sequencing, it is unlikely to be easily detected because STRC and STRCP1 are co-captured and misaligned. Thus, they cannot be discriminated for assembly and can produce false-positive or false-negative variant calls. Previous studies have screened for SNVs in STRC using several combined approaches, including NGS, SNP genotyping, and Sanger sequencing, and excluded pseudogene STRCP1 contamination. Consequently, several SNVs or small indels were identified, although many SNVs may also have been missed5,9,10. Our previous study investigated the frequency of STRC-associated SNHL in 9,956 Japanese individuals using short-read NGS. The results indicated 231 individuals with two-copy loss and 612 individuals with one-copy loss7. Furthermore, 21 SNVs were identified in the 45 individuals. However, because of the STRCP1 pseudogene, it is unlikely that short-read NGS can accurately detect all SNVs.

To overcome the limitations of short-read NGS resolution, the present study intended to use long-read sequencing technology, which has been used in genome research, especially for complex genomic regions, such as those with repetitive or high homology11,12. However, long-read sequencing targeting a single gene has traditionally been considered a resource-intensive approach. In this study, the MinION, an Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platform combined with long-range PCR enabled a cost-effective and practical approach, providing precise alignments in the STRC region despite its high homology with STRCP113,14. The scope of the analysis was limited to specific individuals and intended to detect SNVs rather than structural abnormalities in STRC. Our previous study identified several cases in which heterozygous STRC deletions occurred in one allele (one-copy loss)7. Among these cases, “hidden” STRC variants, in which a compound heterozygous state arises from one-copy loss combined with an SNV in STRC, were anticipated. Consequently, investigations of SNVs on the opposite allele have focused on individuals with a one-copy loss of STRC and mild to moderate hearing loss, a phenotype typically associated with STRC-related SNHL.

The present study used the MinION ONT platform with targeted long-read sequencing to screen unresolved individuals suspected of having an SNV and a heterozygous deletion (one-copy loss) in STRC. Long-read sequencing results were used to assess the capability of SNV detection in STRC by short-read NGS. This study aimed to identify novel pathogenic SNVs in individuals with a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) and evaluate the utility of MinION combined with targeted long-read sequencing as the first step in analyzing the etiology of SNHL in complex genomic regions.

Results

Number of individuals with heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) and mild to moderate SNHL

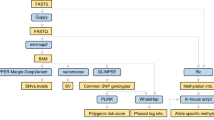

Individuals included in this study were selected from 6,151 unresolved cases after screening 63 deafness genes by short-read sequencing with CNV analysis. From this cohort, 149 individuals were ascertained who exhibited mild to moderate hearing loss and carried a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss), and were therefore subjected to targeted long-read sequencing (Fig. 1).

Workflow and outcomes of targeted long-read sequencing for individuals with unresolved SNHL. From an initial cohort of 6151 unresolved cases, 149 individuals met the inclusion criteria of estimated inheritance patterns, including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and sporadic cases, mild to moderate hearing loss, and one copy loss in the STRC region. Long-range PCR and targeted long-read sequencing identified 27 variants (13 known and 14 novel), resulting in a diagnostic rate of 14.8% (22/149).

Long-range PCR and long-read sequencing with MinION

DNA samples from all 149 selected individuals were enriched, and an adequate concentration for long-read sequencing with MinION was achieved. A long-range PCR amplicon covering the STRC region was expected to produce a 20,343 bp product. The read length distribution of the MinION sequencing data was analyzed using MinKNOW software to validate the size of the long-range PCR products used for targeted sequencing. A histogram of the read lengths for 30 representative samples revealed a marked peak at approximately 20 kb (Supplementary Figure S1). Across all 149 samples, the average read length—calculated from the value in Samtools coverage reports—was 20.76 kb, consistent with a long-range PCR product, indicating that MinION analyzed a single read. The slight extension beyond the expected 20,343 bp was likely attributable to adapter sequences and alignment artifacts, and did not affect the validity of the targeted sequencing approach. The read-mapping plot of long-read sequencing visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software15 showed that a single read covered the entire STRC region, and all reads were derived from the same haplotype, as evidenced by the homozygous genotype of the SNV visualized in the IGV plot (Supplementary Figure S2). This finding provided evidence of the genomic composition of one-copy loss in the STRC region. The number of reads and coverage were highly variable among the samples, and the median number of reads and coverage for the STRC region, including the intron, were 4,088 and 2,780, respectively. If the MinION sequencing reads were aligned to STRCP1 using Samtools version 1.10, the median number of reads and coverage for the STRCP1 region would be 23 and five, respectively, which were notably lower than those for STRC. As shown in Fig. 2, the mean base-quality score was 30.4 for STRC and 23.6 for STRCP1. The mean mapping quality score was 55.1 for STRC and 18.0 for STRCP1. Significant differences were observed between the scores. In contrast, the scores of the previously performed short-read NGS data showed that the mean base quality score was 23.8 for STRC and 24.1 for STRCP1, and the mean mapping quality score was 14.6 for STRC and 5.9 for STRCP1. A representative comparative IGV-based visualization of read mapping between short-read NGS and long-read sequencing is provided as an example in Supplementary Figure S3, showing the improved mapping quality and alignment specificity of long-read data in the STRC region.

Mean base quality and mapping quality scores for STRC and STRCP1 determined using long- and short-read sequencing. Both scores of long-read sequencing for STRC were significantly higher than that of short-read sequencing (t-test: p < 0.05*). Significant differences were observed in comparing scores between STRC and STRCP1 using long-read sequencing, showing better base calling and more correct alignment (t-test: p < 0.05**).

Detected SNVs or small indels

Forty-three of the 149 individuals carried SNVs or small indels (Table 1). In total, 27 variants were identified; 13 variants had previously been reported in patients with hearing loss, and 14 were novel (Fig. 1). Among these, eight variants were categorized as pathogenic, one as likely pathogenic, and 18 as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria. The diagnostic classification was based only on pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Consequently, 22 of the 149 individuals were newly diagnosed with STRC-related hearing loss (14.8%, Supplementary Figure S4). None of the individuals diagnosed as having STRC-related hearing loss harbored only VUS variants. Two variants, c.2303_2313 + 1del and c.5125A > G, were identified as causing hearing loss and registered as pathogenic in ClinVar. However, these two variants should be categorized as benign or VUS because of their high allele frequency in the Japanese control population (ToMMo38K JPN22) and the ACMG criteria standard23,24 (Table 2).

Case presentation

This study addresses an interesting case (Fig. 3). The proband (HL1432) was a 5-year-old female with moderate congenital SNHL. Identical twins exhibited similar SNHL. Their father, who was 37 years old at the time of genetic testing, had experienced mild hearing loss since childhood, despite a lack of family history of the condition in his siblings or parents. They are presumed sporadic or autosomal recessive. A previous short-read sequencing, followed by CNV analysis, was conducted, which identified a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) in the proband, her twin, and her father. The mother, who had normal hearing, also exhibited the same heterozygous deletion (one-copy loss). It was expected that, if both parents had a heterozygous STRC deletion, the child with hearing loss would have been homozygous for the deletion (two-copy loss), resulting in the same phenotype of mild to moderate SNHL. However, the proband and her twin were heterozygous for STRC deletion. This genotype discrepancy between parents and children prompted long-read sequencing with MinION technology for the proband and family members, and a pathogenic variant, c.4549del, was subsequently identified on another remaining allele for the proband, sister, and father, but not for the mother. Consequently, the genotype causing mild-to-moderate SNHL arose from a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) in the mother and the pathogenic SNV in the father to cause STRC-associated SNHL.

Family tree and audiograms of the case presentation. Red and green lines represent right and left hearing thresholds, respectively. Hearing thresholds were averaged across 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. Proband (ID no. HL1432) was a 5-year-old female with congenital moderate SNHL. All affected family members (HL1434 [father], HL1433, and proband) exhibited the same moderate hearing loss (audiograms). Previous short-read sequencing, followed by CNV analysis (line chart), revealed heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) in all individuals, even in the mother with normal hearing. Long-read sequencing identified a pathogenic variant, c.4549del, on another remaining allele for the proband, sister, and father, but not the mother. Consequently, the genotype had arisen from a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) from the mother and pathogenic SNV from the father and caused STRC-associated SNHL.

Discussion

The most commonly used approach in the molecular diagnosis of SNHL is short-read NGS, with a gene panel targeting SNHL-associated genes covering the exonic and adjacent intronic regions. CNV analysis of genes enables the detection of large deletions that cause hearing loss. Although targeted short-read NGS and subsequent CNV analysis can reveal most SNHL genotypes, a substantial proportion of individuals with SNHL remain unresolved. In the present study, targeted long-read sequencing was performed on individuals in whom previous short-read NGS testing had only revealed a heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) despite a strong suspicion that STRC caused the SNHL phenotype. Long-read sequencing technology complements short-read NGS by resolving SNVs in the STRC region that are undetected because of the limitations of short-read sequencing. Heterozygous deletions have been previously identified using short-read NGS, and this study focused on identifying additional pathogenic variants in the same genomic region. Using nanopore MinION long-read sequencing, 27 variants were identified, nine of which were novel and categorized as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to the ACMG guidelines. Consequently, 22 of 149 individuals were newly diagnosed with STRC-related hearing loss (14.8%), as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S4. Regarding the prevalence of STRC-related hearing loss in Japanese SNHL patients, we previously reported it as 2.77%; however, combining these results with findings from the current study raises the estimated prevalence to 2.99%. Francey et al. reported that an SNP genotyping array combined with Sanger sequencing for 659 probands with bilateral SNHL and ten probands with heterozygous deletions, SNVs, or interstitial deletions were identified on the trans allele in four probands, which were defined as compound heterozygotes of CNV and SNV, resulting in hearing loss10. Vona et al. reported homozygous or heterozygous STRC deletions in nine probands among 94 probands with SNHL using whole-genome array comparative genomic hybridization. Among the nine probands with heterozygous deletions and SNVs were identified in the trans allele of four probands9. Mandelker et al. studied long-range PCR combined with short-read NGS for 78 SNHL cases with heterozygous STRC deletions; SNVs were identified in four cases in another allele and were compound heterozygous for SNV5. The incidence of SNVs in the STRC region may vary among populations, and different sequencing methods could influence the results. However, previous studies used molecular diagnosis or conventional clinical DNA testing, which may result in incomplete or missing SNVs in the complex genomic region harboring STRC and the STRCP1 pseudogene. Notably, 21 SNVs were identified in 9,956 Japanese patients with SNHL and STRC-associated hearing loss using short-read sequencing in our previous study7. In the present study cohort, individuals who were previously diagnosed were not included, and all individuals were screened using short-read sequencing. Therefore, individuals in whom SNVs were found in this study were missed by short-read sequencing and were newly discovered SNVs by long-read sequencing. Newly identified variants were observed in exon 2 around exon 20 of STRC, and this region showed high sequence homology to the STRCP1 pseudogene5. Long-read sequencing can enable accurate SNV detection within highly homologous regions, which were previously difficult to analyze. Although nanopore sequencing is known to have a relatively higher per-base error rate for small variant calling than short-read NGS11,12, this limitation can be mitigated with sufficient read depth and coverage. In particular, the longer read length achieved in this study provided superior mapping quality and alignment specificity, allowing us to distinguish STRC from its pseudogene STRCP1. Consistently, the long-read sequencing data in this study showed higher mean base quality scores than short-read NGS data, and the values aligned to STRC were higher than those for STRCP1. Furthermore, the mean base quality and mapping quality scores for STRC in long-read sequencing were significantly higher than those for STRCP1, supporting the conclusion that long-read sequencing enables more accurate read alignment and reliable discrimination between STRC and STRCP1. Notably, the superior mapping quality observed in long-read sequencing is not solely due to long-range PCR enrichment. Rather, the long read lengths enable precise alignment to STRC, as they span regions of high homology with STRCP1. In contrast, short-read sequencing of the same PCR-amplified fragments would still result in ambiguous mapping due to the limited resolution of short reads. The mean mapping quality score was low for short-read NGS, and there was no significant difference between the values of STRC and STRCP1, making it difficult to distinguish between them using short-read NGS. In addition, a sufficient number of reads and depth of coverage would overcome this limitation and yield accurate results, even if several sequence errors occurred.

Long-range PCR was used to enrich the target STRC region. This method was chosen because of its cost-effectiveness for targeted sequencing. Although long-range PCR is highly effective for smaller target regions, such as the ~ 20 kbp STRC region, it has limitations; if large genomic conversions or rearrangements have occurred beyond the amplified region, PCR may have been unsuccessful.

Targeted long-read sequencing may improve the diagnostic rate of genetic SNHL by accurately identifying pathogenic SNVs within complex genomic regions, such as STRC, which are challenging to analyze using short-read NGS. Although previous studies have successfully detected STRC variants with short-read NGS7, this approach remains limited in resolving regions with high homology to pseudogenes, such as STRCP1. None of the variants listed in Table 1 were detected in the prior short-read NGS analysis, likely due to the high sequence homology between STRC and the STRCP1 pseudogene. This supports the notion that these variants were missed owing to limitations in alignment and variant calling. In this study, long-read sequencing enabled the detection of SNVs that were not captured by prior NGS analysis, highlighting its utility as a complementary approach. A direct comparison with our previous short-read NGS results7 demonstrates that long-read sequencing can reveal additional pathogenic variants in individuals previously considered unresolved, thereby enhancing the overall diagnostic yield.

In summary, targeted long-read sequencing was performed using the MinION platform combined with long-range PCR enrichment of the STRC genomic region in 149 individuals with unresolved genetic causes of hearing loss in whom heterozygous STRC deletions were identified through short-read NGS. Fourteen novel and 13 previously reported variants were identified, and 22 individuals were diagnosed with STRC-associated SNHL, with a compound heterozygous STRC deletion in allele 1 and SNVs in allele 2. The integration of long-read sequencing with long-range PCR complements short-read NGS by accurately resolving complex regions of the STRC gene, while reducing pseudogene contamination. This study showed its utility as a secondary analysis to improve the genetic diagnosis of STRC-associated SNHL.

Subjects and methods

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the Shinshu University Ethics Committee and the respective ethics committees of the other participating institutions (approval no. 387–576). Informed consent was obtained from all participants or the parents of the probands for participation in the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Subjects

An in-house database of > 10,000 Japanese individuals with SNHL was established, along with their associated DNA samples and detailed clinical data25. Targeted resequencing analysis with short-read sequencing was performed using the Ion AmpliSeq™ platform (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies), screening for 63 deafness genes combined with CNV analysis. All data were integrated into an in-house database. The genetic cause of SNHL was identified in 3,896 of the 10,047 individuals25. Of the remaining 6,151 individuals with unresolved genetic causes of SNHL, subjects were selected for long-read sequencing analysis under the following inclusion criteria: (1) estimated inheritance patterns based on family history and pedigree analysis included autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and sporadic cases, (2) hearing thresholds were classified as mild hearing loss (21–40 dB) and moderate hearing loss (41–70 dB) based on the pure-tone average (PTA) of air-conduction thresholds at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz for the better-hearing ear, and (3) heterozygous STRC deletion (one-copy loss) was validated with the previously developed CNV analysis8, and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis was also performed if applicable.

Methods

Targeted long-read sequencing of STRC region using MinION

To enrich the target region, long-range PCR was performed using the LA PCR Kit version 2.1 (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the protocol described by Mandelker et al5. Template DNA (100 ng) was added to a 50 µL reaction with primers at a final concentration of 0.8 µmol/L. The primer sequences were as follows: forward, 5´-CAGCTCAGAGTTTTTGATAGGGCTTTCA-3´; reverse, 5´-AGGAAGCAGATCAAAGATTAGTGTCCCTT-3´. Thermocycling conditions were: 94 ℃ for 2 min; 36 cycles of 98 ℃ for 10 s and 68 ℃ for 12 min 10 s; and a final extension at 68 °C for 7 min. Long-range PCR amplified a 20,343 bp, encompassing the STRC region away from the pseudogene STRCP1. The long-range PCR primers, thermal cycler settings, and chemicals were used according to previously published protocols. Long-range PCR products were used to generate sequencing libraries using the ONT ligation sequencing kit (nanopore native barcoding by ligation kit; SKQ-NBD112.96), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each library was barcoded and multiplexed in pools of 43–45 samples, and the pooled library was loaded onto the R9.4.1 flow cell with MinION running for 72 h. Sequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and base calling was performed with MinKNOW version 22.07 using the super accurate mode. NanoFilt version 2.8.0 was used to remove low-quality reads and trim reads < 15,000 bp. The sequence data were mapped against the human genome sequence (build GRCh37/hg19) using Minimap2 version 2.17. After sequence mapping, the DNA variant regions were assembled using Clair3 version 0.1. The number of reads and coverage were calculated using Samtools version 1.10 using command-line Samtools on the targeted region in the range of chr15:43,888,000–43,914,000 for STRC and chr15:43,989,000–44,014,000 for STRCP1. After variant detection, the effects were analyzed using ANNOVAR26. Bioinformatics prediction tools, including SIFT27, PP2HVAR (Polyphen-2)28, REVEL29, and CADD30, were used to evaluate the potential functional impact of the variants. The splicing effects of the candidate variants were assessed using the in silico prediction tool, dbscSNV31. Variants were further selected as less than 1% of several control population databases, including the 1000 genome database32, 6500 exome variants33, The Genome Aggregation Database34, 1200 Japanese exome data from the Human genetic variation database35, the ToMMo 38 K Japanese genome variation database22. The pathogenicity of the identified variants was evaluated according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards and guidelines23, with the ClinGen Hearing Loss Clinical Domain Working Group expert specification24.

Data availability

The human sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the Japanese Genotype–phenotype Archive (JGA, https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/) under the accession number JGAS000842, within the framework of the NBDC Human Database (Research ID: hum0005). These data are available under controlled access, and researchers can apply for access through the NBDC Human Database (https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/).

References

Morton, C. C. & Nance, W. E. Newborn hearing screening–a silent revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2151–2164 (2006).

Yokota, Y. et al. Frequency and clinical features of hearing loss caused by STRC deletions. Sci. Rep. 9, 4408 (2019).

Sloan-Heggen, C. M. et al. Characterising the spectrum of autosomal recessive hereditary hearing loss in Iran. J. Med. Genet. 52, 823–829 (2015).

Shearer, A. E. et al. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genom. Med. 6, 37 (2014).

Mandelker, D. et al. Comprehensive diagnostic testing for stereocilin: An approach for analyzing medically important genes with high homology. J. Mol. Diagn. 16, 639–647 (2014).

Ito, T. et al. Rapid screening of copy number variations in STRC by droplet digital PCR in patients with mild-to-moderate hearing loss. Hum. Genom. Var. 6, 41 (2019).

Nishio, S. Y. & Usami, S. I. Frequency of the STRC-CATSPER2 deletion in STRC-associated hearing loss patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 634 (2022).

Nishio, S. Y., Usami, Moteki H. & S I.,. Simple and efficient germline copy number variant visualization method for the Ion AmpliSeq custom panel. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 6(4), 678 (2018).

Vona, B. et al. DFNB16 is a frequent cause of congenital hearing impairment: Implementation of STRC mutation analysis in routine diagnostics. Clin. Genet. 87, 49–55 (2015).

Francey, L. J. et al. Genome-wide SNP genotyping identifies the Stereocilin (STRC) gene as a major contributor to pediatric bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 158A, 298–308 (2012).

Laver, T. et al. Assessing the performance of the Oxford nanopore technologies MinION. Biomol. Detect. Quant. 3, 1–8 (2015).

Jain, M. et al. Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 338–345 (2018).

Leija-Salazar, M. et al. Evaluation of the detection of GBA missense mutations and other variants using the Oxford Nanopore MinION. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 7, e564 (2019).

Nowak, A., Murik, O., Mann, T., Zeevi, D. A. & Altarescu, G. Detection of single nucleotide and copy number variants in the Fabry disease-associated GLA gene using nanopore sequencing. Sci. Rep. 11, 22372 (2021).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Miyagawa, M., Naito, T., Nishio, S. Y., Kamatani, N. & Usami, S. Targeted exon sequencing successfully discovers rare causative genes and clarifies the molecular epidemiology of Japanese deafness patients. PLoS ONE 8, e71381 (2013).

Kim, B. J. et al. Significant Mendelian genetic contribution to pediatric mild-to-moderate hearing loss and its comprehensive diagnostic approach. Genet. Med. 22, 1119–1128 (2020).

Royer-Bertrand, B. et al. CNV detection from exome sequencing data in routine diagnostics of rare genetic disorders: Opportunities and limitations. Genes (Basel) 12, 9 (2021).

Guan, J. et al. Family trio-based sequencing in 404 sporadic bilateral hearing loss patients discovers recessive and De novo genetic variants in multiple ways. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 64, 104311 (2021).

Jin, X. et al. Variant analysis of 92 Chinese Han families with hearing loss. BMC Med. Genom. 15, 12 (2022).

Baux, D. et al. Combined genetic approaches yield a 48% diagnostic rate in a large cohort of French hearing-impaired patients. Sci. Rep. 7, 16783 (2017).

Japanese Multi Omics Reference Panel https://jmorp.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp. (Accessed 14 April 2023) (2023).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Oza, A. M. et al. Expert specification of the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines for genetic hearing loss. Hum. Mutat. 39, 1593–1613 (2018).

Usami, S. I. & Nishio, S. Y. The genetic etiology of hearing loss in Japan revealed by the social health insurance-based genetic testing of 10K patients. Hum. Genet. 141, 665–681 (2022).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucl. Acid. Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Ng, P. C. & Henikoff, S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucl. Acid. Res. 31, 3812–3814 (2003).

Adzhubei, I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Method. 7, 248–249 (2010).

Ioannidis, N. M. et al. REVEL: An ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 877–885 (2016).

Rentzsch, P., Witten, D., Cooper, G. M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucl. Acid. Res. 47, D886–D894 (2018).

Jian, X. et al. In silico prediction of splice-altering single nucleotide variants in the human genome. Nucl. Acid. Res. 42, 13534–13544 (2014).

The International Genome Sample Resource http://www.1000genomes.org/ (Accessed 14 April 2023) (2023).

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ (Accessed 14 April 2023) (2023).

Genome Aggregation Database https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org (Accessed 14 April 2023) (2023).

Human genetic variation database https://www.hgvd.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp (Accessed 14 April 2023) (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the Deafness Gene Study Consortium for providing samples and clinical information and Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language review.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (S.U. 16kk0205010h001 and 15ek0109114h001) and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (H.M. 23K08910).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: H.M. and N.S.; data acquisition: H.M. and N.S.; bioinformatics analysis: H.M. and N.S.; PCR and sequencing analysis: H.M. and N.S.; data analysis and interpretation: H.M. and N.S.; writing the manuscript: H.M. and N.S.; and study supervision: S.U. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Shinshu University Ethical Committee and the ethical committees of the other participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or the parents of the proband for participation in this study, which was approved by the ethics committee of each institution.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moteki, H., Nishio, Sy. & Usami, Si. Targeted long-read nanopore sequencing as a complementary approach for detecting STRC variants and distinguishing the STRCP1 pseudogene. Sci Rep 15, 44261 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27816-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27816-x