Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted, and repetitive behaviors. Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota alterations may contribute to ASD pathogenesis via the gut-brain axis. However, many previous studies have not adequately controlled for confounding genetic and environmental variables. In this study, we examined the gut microbiota profiles of 19 children with ASD, 8 siblings with non-ASD, and 36 parents from 17 families, providing a unique design that minimized biases related to shared genetic and familial environments. Metagenomic sequencing revealed significant differences in gut microbiota diversity and composition between groups. Specifically, children with ASD had lower abundances of Bifidobacterium and higher abundances of both Bacteroides and Clostridium species compared to their siblings, with notable dysbiosis correlated to ASD-specific symptoms. These findings highlight the potential role of microbiota alterations in ASD pathogenesis and suggest familial microbiota traits influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Further exploration of gut microbial therapies could offer promising avenues for ASD intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired social interaction, communication challenges, and repetitive behaviors and restricted interests1. The global prevalence of ASD has been rising rapidly in recent years. According to the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, data from 11 U.S. sites in 2020 estimated the prevalence of ASD at 27.6 per 1000 children aged 8 years, which translates to approximately one in 36 children2. This notable increase has driven extensive scientific efforts to unravel the underlying mechanisms of ASD and develop effective strategies for early intervention and treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that alterations in gut microbiota may play a pivotal role in ASD. Studies have consistently reported significant differences in gut microbiota composition between individuals with ASD and neurotypical controls3. For instance, Kang et al.4 observed a significant reduction in the abundance of the genera Prevotella, Coprococcus, and unclassified Veillonellaceae in the gut microbiota of children with ASD. Moreover, elevated levels of Clostridium have been associated with gastrointestinal issues, such as diarrhea and constipation, commonly observed in children with ASD5. Beyond compositional changes, the functional roles of gut microbiota and metabolic byproducts are gaining increasing attention. For example, studies demonstrated that certain microbial metabolic, such as short-chain fatty acids, may influence brain development and behavior by crossing the blood–brain barrier6,7. These findings underscore the potential importance of microbiota-host interactions in the neurodevelopmental and gastrointestinal aspects of ASD. Despite the growing body of research, discordant findings regarding microbiota diversity remain a challenge in the field. While Plaza-Díaz et al.8 reported the gut microbiota composition in children with ASD was altered, but their overall diversity showed no significant difference compared to neurotypical controls. Similarly, Xie et al.9 observed there was no significant difference of alpha and beta diversity between children with ASD and the control group . In contrast, both Cao et al.10 and Ye et al.11 found that children with ASD have a higher alpha diversity in their gut microbiome compared to control groups. These inconsistencies may be attributable to factors such as geographical location, dietary habits, and cultural differences, all of which shape the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota.

Host genetics play a significant role in shaping the composition and function of the gut microbiota. Evidence from studies on twins highlights the influence of genetic factors, with host genetics impacting the abundance and diversity of gut microbial communities12. This genetic influence extends to autism, where a strong relationship between genetic predisposition and autism prevalence has been well-documented. Twin studies, for instance, show markedly higher concordance rates of autism in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins, underscoring the pivotal role of genetic factors13. Furthermore, familial genetic risk has been estimated to account for 50% to 80% of the prevalence of autism, as reported in a study by Sandin et al.14. This overlap between genetic susceptibility to autism and the heritability of gut microbiota composition provides a compelling framework for understanding the shared contributions of genetic and environmental factors. These findings underscore the potential for familial environment and genetic predisposition to drive microbiota alterations in individuals with ASD. Understanding these interactions is critical for interpreting the shared familial traits in gut microbiota observed in children with ASD, particularly when considering how shared genetics and family environment may simultaneously influence microbiota composition and autism phenotypes. Integrating host genetic factors into microbiome-focused studies of autism could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between these systems.

Although extensive research has examined the gut microbiota in children with ASD, relatively little attention has been given to the gut microbiota of family members of individuals with autism15. Studies highlighted the influence of maternal gut microbiota on shaping a child’s gut microbiome through maternal-infant transmission during pregnancy and lactation, which could contribute to autism risk16,17. A study by Kurokawa et al.18. found that, compared to their neurotypical siblings, children with ASD had significantly lower gut microbiota alpha-diversity. Interestingly, this study found no significant differences in dietary diversity among the groups, suggesting that the observed microbiota differences may be linked to the pathophysiology of ASD itself, rather than simply being a result of dietary habits. In contrast, a study by Abuljadayel et al.19 reported that children with ASD exhibited higher microbial biomass, diversity, and richness, along with a greater abundance of pathogenic genera. A systematic review also noted that. These findings suggest that genetic predispositions may significantly influence gut microbiota composition. However, the potential confounding factors of shared environments, dietary habits, and lifestyles raise questions about causality. To address this, an Australian cohort study applied methods to mitigate these confounders, concluding that ASD-related microbiota differences may be linked to dietary preferences associated with autism rather than the microbiota being a primary causal factor. This finding underscores the complexity of disentangling the roles of diet, genetics, and environment in shaping the gut microbiota of individuals with ASD20. Overall, these insights highlight the need for further research to clarify the interplay between genetics, family environment, and dietary factors in influencing the gut microbiota of individuals with ASD and their family members.

The primary objective of this study is to establish a family cohort of children with ASD, by comparing the gut microbiota diversity, community composition, and metabolic functions among children with ASD, their non-ASD siblings, and their parents, to reveal ASD-associated gut microbial dysbiosis and explore the respective influences of genetic and environmental factors on the microbial composition, thereby providing potential biomarkers for future precision diagnosis and treatment.

Methods and materials

Study design

This study included 63 participants aged 1–45 years who were recruited for intestinal microbiota analysis from 2018. Participants were divided into two main groups: an ASD group and a control group. The ASD group consisted of 19 children diagnosed with ASD from the Department of Pediatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine. Diagnosis was conducted by pediatric specialists following the criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. The control group consisted of 44 individuals, including 36 parents of the children with ASD (17 fathers and 19 mothers), and 8 neurotypical neurotypical siblings of the children with ASD as a comparison group to minimize biases from age-related differences in gut microbiota. All families were instructed to follow the dietary guidelines issued by the State Council of China for three months prior to sample collection. During this period, participants were regularly contacted by phone to ensure that they adhered to the guidelines. This approach was designed to ensure consistency in dietary habits across the study groups and minimize the potential influence of diet-related biases on the gut microbiota. Inclusion criteria: Participants were included in the study if they had not taken antibiotics, probiotics, or other medications that could potentially alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Exclusion criteria included individuals with diagnoses of schizophrenia, other mental illnesses, mood disorders, or a history of epilepsy seizures within the past year. Exclusion criteria: patients with schizophrenia, other mental illnesses, mood disorders, and epilepsy attacks in the past year. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine (Approval Number: LW 2024-005). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Before participation, the study was thoroughly explained to all participants, and written informed consent was voluntarily obtained from all participants or their legal guardians.

Sample collection and processing

Fecal samples were collected from all participants. DNA was then extracted from these samples, followed by library construction and sequencing using the Illumina platform. All raw metagenomic sequencing data were quality-controlled using MOCAT2 software21. First, the software Cutadapt (v1.14, parameters: -m30) was used to trim adapters from all raw sequencing reads22. Then, the SolexaQA package was used to filter out reads with a quality score below 20 and lengths shorter than 30 bp23, resulting in clean reads. Finally, the filtered reads were aligned to the host genome using SOAPaligner (v2.21, parameters: -M4-l30-v10) to remove contaminant host reads24, yielding high-quality clean data.

Sequence assembly and annotation

High-quality reads were de novo assembled using SOAPdenovo (v2.04, parameters: all-D1-M3-L500)25. The K-mers for each sample were statistically derived by MOCAT2 based on the length and number of sample reads. Reads were broken into K-mers to construct a de Bruijn graph, and Eulerian Path was used to assemble them into contigs. Then, based on the positional relationship of the pair-end reads, they were connected into scaffolds, and continuous contigs were selected from scaffolds to obtain scaffolds with lengths greater than 500 bp. Based on the scaffolds, MetaGeneMark was used for gene structure prediction26. The predicted genes were clustered and deduplicated using CD-HIT27. If the sequences of two genes were more than 95% consistent and the overlap region covered more than 90% of the shorter sequence, these two genes were clustered into one, and the longest sequence in the cluster was chosen as the representative sequence, constructing a non-redundant gene set with gene lengths greater than 100 bp. We used DIAMOND 28 (v0.7.9.58, parameters: blastp-v–sensitive-k10) to align the obtained non-redundant reference gene set to the KEGG Orthology, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), Virulence Factor Database (VFDB)29, and Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database (CAZy) for functional annotation of all predicted genes. The Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database (ARDB) was functionally annotated using the recommended tools on its website30.

Quantification of microbial abundances

At the genetic level, high-quality reads are aligned to the constructed non-redundant reference gene set using BWA31, removing reads shorter than 30 bp and those with consistency below 95%, obtaining the read count of each gene, and then standardizing to obtain the relative abundance of genes. At the species and higher taxonomic levels, the relative abundance of the microbial community is obtained using MetaPhlan2.0. MetaPhlan2.032 predicts relative abundance at different taxonomic levels using over one million marker genes from ~ 7500 species (an average of 184 genes per species). Additionally, MOCAT2 is used for analysis of species with unknown genome sequences based on mOTU (metagenomic operational taxonomic units), obtaining the relative abundance of mOTUs. At the metabolic pathway level, HUMAnN233 is used to align reads to its customized database, obtaining the relative abundance at the gene family level from the UniProt Reference Cluster and at the metabolic pathway level from the MetaCyc database34. After aligning genes to each database using DIAMOND and performing functional annotation, the relative abundance at each functional level is obtained by simply summing the abundance of genes annotated to that function.

Microbial diversity analysis

Alpha diversity includes indices such as richness, evenness, and Shannon diversity, which describe the diversity of species within a sample. We used the diversity function from the R package vegan35 to calculate these indices. To adjust for biases caused by different sequencing depths among samples based on metagenomic read count data, we performed rarefaction using the rarefy function36. Using the PCoA analysis method based on Bray–Curtis distance, we displayed the similarities and differences between different samples on a two-dimensional coordinate system. PCoA selects the top-ranked eigenvalues to represent distance differences between samples by sorting eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Additionally, we used the similar percentage (SIMPER) method37 to determine the main causes of community differences.

Statistical analysis

We use PERMANOVA (Permutational multivariate analysis of variance)38 to assess the impact of phenotypic variables (such as disease status, age, and gender) on sample differences. PERMANOVA is calculated using the adonis2 function from the vegan package, with p-values obtained through 1000 permutations. We use two methods for inter-group difference analysis to analyze the differences in genes, functions, and taxa between two groups. For relative abundance, we use the Wilcoxon test to compare the relative abundance between two groups, identify significantly different units, and correct the p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, setting the corrected p-value threshold at 0.05. We apply the same method to obtain p-values at the functional levels of KEGG/ARDB/VFDB/COG/CAZy. For count data (read count), since count data do not follow a normal distribution, the DESeq239 method is used to transform the data before calculating differences.

LEfSe40 analysis allows for comparisons between two or more groups to find biomarkers with significant abundance differences between groups. LEfSe first uses the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test to detect species with significant abundance differences between different groups, then uses the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to analyze inter-group differences for species identified in the previous step, and finally employs linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to reduce dimensionality and assess the impact of significantly different species (i.e., LDA score). Considering other factors affecting gut microbiota, such as age, gender and group., we use the multivariate linear association model (MaAsLin)41 to analyze the relationships between these factors and gut microbiota, as well as microbiota functions. This method employs a generalized linear model, and due to the sparsity of metagenomic data, MaAsLin uses a boosting method to screen potential phenotypic variables related to gut microbiota. We conduct multivariate association analyses using the results of Metaphlan2 and HUMAnN2 respectively.

Pathway enrichment and metabolite analysis

For the relative abundance of KEGG Orthology (KO), we used the GAGE package42 from R/Bioconductor for KEGG Pathway enrichment analysis, with significant pathways displaying the increased or decreased gene abundance of KO in the pathways using pathview43. The gut microbiota can generate and consume many metabolites. For a specific metabolite, we estimate the potential of the gut microbiota to generate or consume the metabolite by cumulatively adding the abundance of the microbiota that generate the metabolite while subtracting the abundance of the microbiota that consume the metabolite. We also estimate the differences in metabolic potential between different groups. It is important to note that this analysis is based on the predicted metabolic potential from metagenomic data and does not represent directly measured metabolite concentrations.

Results

Study characteristics

This study enrolled a total of 63 individuals, stratified into three groups, the first group consisted of 19 children diagnosed with ASD (mean age 4.96 ± 1.14 years; age range 3–8), which showed a strong male predominance (17 boys, 2 girls; 89.47% male). In contrast, the second group of 8 neurotypical siblings (HC-c; mean age 10.88 ± 1.73 years; age range 8–13) was predominantly female (3 boys, 5 girls; 37.5% male). The third group was composed of 36 parents (HC-fm; age range 28–45), including 17 fathers and 19 mothers (47.2% male). Clinical characterization of ASD cohort yielded mean scores of 36.95 on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), 92.37 on the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), 125.53 on the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC), and 61.05 on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), as detailed in Table 1.

Differences in microbial composition among groups

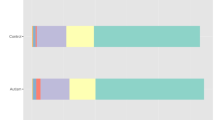

To explore the gut microbial composition, the relative abundance of microbes was calculated and visualized for four groups: children with ASD, their neurotypical siblings (HC-c), their fathers (HC-f), and their mothers (HC-m) (Fig. 1). The composition varied noticeably across these groups at both the phylum and genus levels. At the phylum level, a clear age-related pattern was apparent. The relative abundance of Actinobacteria was considerably higher in the child groups (both ASD and HC-c) compared to the adult groups (HC-f and HC-m). This observation suggests age is a major factor shaping the microbiota. At the genus level, Bifidobacterium also showed a strong age-related effect, being highly abundant in children (ASD and HC-c) but nearly absent in adults (HC-f and HC-m). Interestingly, when comparing between the children, the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium appeared to be lower in most children with ASD compared to their neurotypical siblings (HC-c). This specific finding aligns with the results of Ahmed et al.44. Additionally, Prevotella was generally more abundant in the adult groups than in the child groups. The results indicate that while age is the primary driver shaping the human gut microbiota, children with ASD exhibit a specific gut dysbiosis—characterized by a reduction in key beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium—even within a shared familial environment and genetic background.

Gut microbiota composition and relative abundance across study groups. Stacked bar plots illustrating the relative abundance of gut microbiota for each individual sample at the phylum level and the genus level. Each vertical bar represents a single sample, arranged on the x-axis by cohort: ASD, HC-c, HC-f, and HC-m. The most abundant taxa are color-coded as indicated in the legends. Taxa with lower relative abundance are grouped into the other category.

Further analysis of specific taxa revealed significant variations in the phylum Actinobacteria across the four groups (ANOVA, p = 5.10e−4, Fig. 2). A clear age-related pattern was observed, with both child cohorts exhibiting the higher and more variable proportion of Actinobacteria compared to the more stable levels and lower levels in the adult parent cohorts (HC-f and HC-m). This pattern suggests a potential age-related effect, as both child groups (ASD and HC-c) showed different abundance profiles compared to the adult groups (HC-f and HC-m). The abundance of Actinobacteria was notably lower in the ASD group compared to their sibling group, suggesting an altered gut microbiota structure in these children that could potentially impact physiological function. Additionally, we observed a significant group difference in the class Flavobacteriia (ANOVA, p = 0.030). The most striking finding was the near-complete depletion of Flavobacteriia in the ASD group, whereas it was present in the neurotypical sibling, mother, and father groups. While microbiota composition is known to be closely linked to diet type45, this is unlikely to be the primary driver in our study, as family members largely shared a consistent diet. This finding suggests that non-dietary factors, such as host genetics or specific environmental exposures, may play a more dominant role in modulating Flavobacteriia levels. This hypothesis is supported by landmark studies demonstrating that non-dietary environmental factors46 and host genetic12 are powerful determinants of gut microbiota composition. Therefore, the observed depletion of Flavobacteriia in children with ASD warrants further investigation into these non-dietary factors.

Differential abundance of Actinobacteria and Flavobacteriia across study groups. The box plot represents the significantly different bacteria between the ASD and control groups at the class level, while the bar chart shows the relative abundance of these significantly different bacteria in each sample at the class level, and the red arrows indicate females.

Alpha diversity analysis

Alpha diversity of the gut microbiota was assessed using the Shannon index, which reflects overall species diversity (incorporating both richness and evenness), and the Chao1 index, which estimates species richness. The analysis of species diversity (Shannon index, Fig. 3A) revealed that the mother group (HC-m) exhibited the highest median diversity, closely followed by the ASD group. Both the HC-m and ASD groups showed markedly higher diversity compared to the father (HC-f) and neurotypical sibling (HC-c) groups (p < 0.05). A similar pattern was observed for species richness (Chao1 index, Fig. 3B), where the HC-m group again displayed the highest median richness. Notably, the diversity of the ASD group was comparable to that of the mother group, and both were substantially higher than the diversity observed in the HC-f and HC-c groups. These findings are particularly striking and stand in contrast to a significant body of literature reporting lower alpha diversity in children with ASD compared to neurotypical controls3,46. Our results do not indicate a diversity deficit in the ASD group. Instead, they reveal a surprisingly robust gut microbial community in children with ASD, characterized by high levels of both species richness and overall diversity, on par with the maternal microbiome, which was the most diverse within the family unit. This unexpected similarity between the ASD child and mother could suggest the strong influence of shared early-life environment, diet, or vertical transmission of microbes. It posits that the gut dysbiosis in ASD may not be a simple loss of diversity, but a more complex alteration in community composition and function, which warrants further taxonomic investigation.

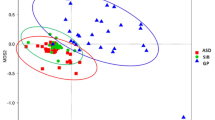

Beta diversity analysis

To further explore the beta diversity of species composition among different groups, we used the PCoA analysis method based on the Bray–Curtis distance to illustrate differences in microbial community structures between samples (Fig. 4A). Overall, there were significant differences in the gut microbial community structures among the groups. Visually, a clear separation was observed between the ASD group and the HC-c group, suggesting a distinct difference in their gut microbiota structures. Samples in the HC-c group were closely clustered, wherea those in the ASD group were more dispersed. The sample points of the HC-f and HC-m parent groups were relatively scattered, and their distances from the children’s group samples were substantial. PERMANOVA (Fig. 4B) results confirmed that the grouping factor had a significant effect on the microbial community structures (PERMANOVA, R2 = 0.1414, p = 0.001), explaining 14.1% of the variation among samples. As shown in Fig. 4, the HC-c group exhibited more pronounced differences compared to other groups, particularly when contrasted with the ASD group. The HC-f and HC-m groups were more similar to each other, suggesting that age is also a major factor influencing the gut microbiome structure.

Further analysis of the main species contributing to differences in gut microbiota across groups (Table 2) reveals that species within the genera Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Clostridium are among the most dominant. According to previous research47, an overabundance of Bacteroides—especially during early life—may have functional implications for individuals with ASD. Consistent with these findings, our study observed a higher abundance of several Bacteroides species, notably Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides massiliensis and Bacteroides nordii, in the ASD group compared to the HC-c group. In stark contrast, Bifidobacterium, a genus known for its probiotic effects, was most prevalent in the HC-c group. Our study evealed a marked reduction in the abundance of beneficial species like Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum in children with ASD compared to their neurotypical counterparts, which is consistent with prior studies. Conversely, The pattern for the Clostridium genus was more nuanced. While several species, such as Clostridium symbiosum and Clostridium citroniae were found at elevated levels in the ASD.

group. The finding aligns with research indicating that gastrointestinal symptoms3,5,46, it is noteworthy that Clostridium bartlettii showed a slightly lower abundance in ASD children. This highlights the species-specific role of Clostridium in the gut ecosystem48.

We applied several statistical methods to identify species-level differences for three key genera—Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Bifidobacterium—which are frequently implicated in gut health and dysbiosis (Fig. 5). Across the analyses, certain microbes repeatedly emerged as significantly associated with ASD. Error bar analyses revealed that both Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides nordii were significantly more abundant in the ASD group compared to the parental group (HC-f and HC-m) (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). This finding aligns with previous research reporting higher Bacteroides levels in autistic individuals48. Across the multiple analyses, Bacteroides species consistently appeared as markers of a perturbed microbial community in ASD, strengthening the inference that they could play a role in the condition’s pathogenesis. In contrast, species known for their beneficial effects, particularly within the Bifidobacterium genus, were depleted in the ASD group. Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, and Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum all showed significantly lower abundance in ASD children compared to their neurotypical siblings (HC-c) (p < 0.05). Notably, the HC-c group exhibited the highest levels of these species. This consistent observation of lower Bifidobacterium levels in ASD, in both error bar and other statistical analyses, reinforces earlier studies suggesting that Bifidobacterium breve may alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms and modulate neuroactive compounds, such as serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor49. The pattern for the Clostridium genus was more complex, our analysis demonstrated that the abundance of Clostridium symbiosum and Clostridium citroniae was significantly elevated in the ASD group compared to the parental group (p < 0.05). This aligns with prior research linking certain Clostridium species to gastrointestinal disturbances in ASD 50. However, it is important to note that not all species followed this trend; for instance, the abundance of Clostridium bartlettii was lower in the ASD group compared to the HC-c group. These species-specific variations suggest that an overrepresentation of particular Clostridium species rather than the genus as a whole, may contribute to the gut–brain axis dysregulation observed in ASD.

Analysis of the significant difference in bacterial strains between the two groups. Left Side shows the mean proportions (in percentage) for groups. The bars represent the averages, indicating the relative prevalence or characteristics being measured in the two groups. Right Side illustrates the difference in mean proportions between the two groups, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals. A point estimate (blue circle) indicates the specific difference in proportions, with horizontal lines showing the confidence intervals for this difference.

Additionally, we used LEfSe to identify units with significant differences at various taxonomic levels. LEfSe analysis further determined microbial species with significantly different abundances between the ASD group and the control group. Figure 6 displays the results of the LEfSe analysis, which identifies statistically significant biomarkers between the ASD and HC-c groups. It includes a cladogram illustrating the phylogenetic distribution of these biomarkers and a bar plot ranking them based on their Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores. The cladogram visually highlights that taxa belonging to the class Flavobacteriia, including the order Flavobacteriales and family Flavobacteriaceae, were the most prominent biomarkers for the HC-c group. Conversely, multiple taxa within the class Clostridia were identified as being enriched in the ASD group. Further LDA found linear combination features between the ASD and control groups. The two groups have 29 significantly different taxa, with 15 dominant distinguishing features in the ASD group. Notably, Eubacterium rectale emerged as the top biomarker for the ASD group, exhibiting the highest LDA LDA effect size. This finding is particularly interesting as it contrasts with some previous studies that reported a depletion of Eubacterium rectale in individuals with ASD51. This discrepancy highlights the complexity of microbiota alterations in ASD and may reflect differences in study cohorts, dietary factors, or methodologies, warranting further investigation.

Linear discriminant effect size (LEfSe) analysis. Left Panel is a circular cladogram, which illustrates the evolutionary relationships among different biological entities, likely species or taxonomic groups. The branches are color-coded, with red representing the group labeled “ASD” and green for “HC-c.” Right Panel displays LDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis) scores for various taxa, comparing the two groups. The y-axis lists different taxa, while the x-axis represents the LDA score on a logarithmic scale. Positive scores are shown in green (indicating a stronger association with “HC-c”) and negative scores in red (indicating a stronger association with “ASD”). The lengths of the bars indicate the strength of the discriminative power of each taxon between the two groups.

Pathway enrichment analysis

We further used enrichment analysis to obtain KEGG pathways with significant differences between different groups. Table 3 shows that pathways such as Biofilm formation—Escherichia coli and ABC transporters show increased gene abundance, while pathways such as Methane metabolism and Mitophagy—yeast are decreased in gene abundance. According to relevant literature, the observed upregulation of biofilm formation pathways, which have been hypothesized in other literature to influence gut barrier integrity and may thereby be associated with gut-brain axis signaling. The decreased in gene abundance of Methane metabolism suggests that changes in gut microbiota affect methane metabolism, potentially influencing neural functions. The increased gene abundance of ABC transporters, which is involved in substance transport, may affect neurotransmitter levels and brain functions. The decreased in gene abundance of Meiosis—yeast indicates that abnormal Meiosis may lead to genetic changes, impacting neural development. The decreased in gene abundance of Mitophagy—yeast suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction is related to autism pathology. The decreased in gene abundance of Various types of N-glycan biosynthesis indicates that abnormal glycosylation may affect neural interactions and development. The increased gene abundance of Transcriptional misregulation in cancer suggests that gene expression dysregulation may lead to developmental disorders. The defect in Non-homologous end-joining, a DNA repair mechanism, may cause genomic instability, impacting neural development.

Figure 7 illustrates the signaling pathways involved in biofilms formation in Escherichia coli, primarily regulated by the cAMP/CRP pathway and the c-di-GMP pathway. These pathways enable E. coli to adapt to stressful conditions, such as nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, or low temperatures, by switching between motile and sessile states Recent studies suggest that the gut microbiota of individuals with autism differ from that of individuals with non-ASD, with biofilms potentially playing a key role in shaping and stabilizing microbial communities. This alteration in gut microbiota could impact gut health and function, which may indirectly influence autism symptoms. Biofilms may also trigger immune responses, potentially altering the gut environment and affecting brain development and function. Interestingly, certain genes may have dual roles, contributing to both biofilm formation and neurological processes, possibly influencing neural signaling or connections. Additionally, bacterial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, can modulate neurotransmission via the gut-brain axis, with their production and regulation linked to biofilms activity. Overall, the interplay between biofilms, gut microbiota, immune responses, and metabolic pathways may provide insights into the potential connection between microbial dynamics and autism pathogenesis.

A pathway enriched based on KO. Green and red color indicate decreased in gene abundance and increased in gene abundance of certain pathways respectively. KEGG pathway maps were adapted from Kanehisa Laboratories52.

Characterization of the metabolic associated with ASD

Finally, we analyzed the metabolic differences between groups from a functional metabolic perspective, as shown in Fig. 8. Regarding the metabolite trimethylamine (TMA), the ASD and HC-C groups exhibit distinct abundance patterns between genders, with higher relative abundance of TMA observed in males from the ASD group. Elevated TMA levels could suggest alterations in gut microbial activity or nutrient metabolism influenced by gender-specific factors in ASD. The relative abundance of ammonia (NH3) was also observed to be higher in the ASD group compared to the HC-C group. Increased NH3 abundance may be indicative of disruptions in protein or nitrogen metabolism. The enrichment of pathways related to ammonia production suggests a potential for increased ammonia levels, a metabolite that has been linked to neurotoxic effects in other contexts. Individuals with ASD may display abnormalities in NH3 cycling and excretion mechanisms, potentially contributing to its accumulation and subsequent neurotoxicity. These disruptions may play a role in the pathophysiology of ASD. Acetone levels demonstrated variability across groups and between genders, though no consistent increasing or decreasing trend was evident. This suggests that changes in acetone may be linked to alterations in energy or the remodeling of metabolic pathways. Previous studies have reported that individuals with ASD may experience abnormalities in energy metabolism, particularly in pathways associated with brain energy production and utilization, which would partially explain these observed variations. Metabolites such as L-alanine and L-glutamine showed significant differences in their abundance between the ASD and the HC-C groups, with an upward trend in the relative abundance of these compound in ASD group. L-alanine is a key metabolite involved in amino acid transfer pathways and may influence neurotransmitter synthesis and function, impacting neurodevelopmental processes. Similarly, L -glutamine, a precursor to the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in the brain, displayed increased abundance in ASD. This finding is noteworthy given that glutamate imbalance is often implicated in the altered neuronal signaling and excitatory-inhibitory imbalance commonly observed in ASD.

Discussion

This study provides a multi-dimensional comparison of the gut microbiota among children with ASD and their core family members (neurotypical siblings and parents), systematically uncovering ASD-associated microbiome signatures and offering new functional insights into its potential pathophysiological mechanisms. The central finding of this study confirms that the gut microbiota of children with ASD exhibits significant and unique characteristics in its overall structure, species composition, and functional potential when compared to their cohabiting neurotypical siblings and parents. The β-diversity analysis (PCoA plot) clearly shows that the ASD group’s microbiota forms a distinct cluster, significantly separated from all neurotypical control groups (ANOSIM, R = 0.1414, p = 0.001). This strongly supports the prevailing view that gut dysbiosis is a common biological feature of ASD53,54,55. Recent study has increasingly pointed to gut dysbiosis as a potential biomarker for ASD56. By including family members as controls, our design effectively accounts for key confounding variables such as shared genetic background and early environmental exposures (e.g., family dietary patterns) 57, thereby more reliably isolating the microbial differences directly associated with ASD.

In terms of specific microbial composition, our results are highly consistent with numerous reports in the literature. For instance, we observed a significant depletion of beneficial bacteria known for their immune-modulating and gut-barrier-protective functions, such as the genus Bifidobacterium, particularly B. breve and B. longum, in ASD children compared to their neurotypical siblings (HC-c) (species difference plot). This finding echoes the conclusions of multiple cohort studies suggesting that the depletion of beneficial commensal bacteria may be a key driver of ASD-related gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms58,59. The abundance of B. longum is closely linked to host age and health status60, while both B. breve and B. longum are pioneer colonizers of the infant gut, and their early absence could have long-term consequences for immune system maturation and neurodevelopment61. Concurrently, LEfSe analysis revealed a significant enrichment of taxa in the ASD group, including several unclassified genera within the order Clostridiales and Eubacterium rectale (Cladogram). Together, these findings paint a picture of ASD-related gut dysbiosis characterized by a “decrease in beneficial bacteria and an increase in potential opportunistic pathogens,” which aligns with the consensus in the field.

However, one of the most striking findings of our study is that the α-diversity (Shannon and Chao1 indices) in children with ASD was significantly higher than in their neurotypical siblings (HC-c) (alpha diversity violin plots). This result contrasts sharply with many studies that have reported reduced or non-significant differences in microbial diversity in ASD children62. We argue that this “paradoxical” phenomenon highlights the complexity and heterogeneity of ASD microbiome research. As noted in several reviews, current findings are inconsistent, likely influenced by factors such as geographic location, sequencing methods, age, and sex63,64. We therefore propose a plausible hypothesis: in the gut ecosystem of children with ASD, “high diversity” may not equate to “health” but could represent a state of “pseudo-diversity” or “pathological diversity” driven by an unstable community structure and the overgrowth of opportunistic pathogens. In such a state, the stability of core functional taxa (like Bifidobacterium) may be compromised, creating an environment conducive to the production of harmful metabolites65,66. Furthermore, our preliminary observations suggest that some metabolites considered neurotoxic, such as Trimethylamine (TMA) and ammonia (NH3), appear to be more elevated in older ASD children (metabolite heatmap). While this observation requires validation in larger longitudinal studies, it offers a new perspective for understanding the chronic nature and symptomatic evolution of ASD, suggesting that the metabolic consequences of dysbiosis may accumulate with age67.

A key discovery is the upregulation of the “Biofilm formation—Escherichia coli” pathway in the microbiota of the ASD group (KEGG pathway map). Biofilms are protective matrices formed by microbial communities that help bacteria resist host immune clearance, antibiotics, and environmental stress. Based on this, we put forward a hypothesis: certain opportunistic pathogens in the gut of children with ASD (such as some pathogenic strains of E. coli) may enhance their biofilm-forming capabilities to establish persistent “micro-ecological lesions” on the intestinal wall. These lesions could not only act as a continuous trigger for chronic, low-grade inflammation but also alter intestinal barrier permeability, leading to a “leaky gut.” This would allow bacterial products (like LPS) and harmful metabolites to enter the bloodstream and ultimately affect neurodevelopment and function via the “microbiota-gut-brain axis” 55,68 This offers a novel framework for understanding ASD-related immune abnormalities and why some children respond poorly to interventions like probiotics—the interventions may fail to penetrate and dismantle these mature biofilms.

Furthermore, the enrichment of the ABC transporters pathway provides another critical clue. The ABC transporter family has diverse functions, including nutrient uptake, toxin efflux, and drug metabolism. Alterations in this pathway may indicate that the gut microbiota of ASD children has unique capabilities in processing and transporting small molecules, which is consistent with the view that microbial metabolism is central to microbiota-host interactions65. This change might partially explain, from a microbial standpoint, why children with ASD often present with metabolic abnormalities, such as malabsorption of certain food components, distinct dietary preferences, or increased sensitivity to environmental chemicals.

In summary, the significance of this study is threefold: (1) It provides evidence of gut dysbiosis in ASD through a family-based control design. (2) It challenges the singular narrative of “reduced α-diversity” by introducing the concept of “pathological high diversity.” (3) Most importantly, by uncovering novel functional pathways like “biofilm formation,” it proposes specific, testable hypotheses about how the microbiota may influence ASD pathophysiology, advancing the field from “microbiota-disease association” to “microbiota-function-disease mechanism.”

Nevertheless, we must cautiously acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, its cross-sectional design only allows for the identification of associations, not the establishment of causality. We cannot determine whether the observed gut dysbiosis is a cause of ASD, a consequence, or a product of complex interaction. For example, the picky and restrictive eating behaviors common in children with ASD are themselves a powerful driver of gut microbiota remodeling, which in turn is a key factor influencing the child’s metabolomic profile57. Future research urgently requires longitudinal designs, tracking high-risk cohorts from infancy, to capture the temporal relationship between microbial changes and the onset of ASD symptoms. Second, regarding the sample design, while the use of family-based controls is a major strength—effectively controlling for genetic and environmental confounders—the limited sample size (e.g., the sex bias in the ASD group) remains a primary limitation. This restricts the statistical power for deeper subgroup analyses (e.g., based on sex differences, gastrointestinal symptoms, ASD severity, or medication history) 69,70. Although robust statistical methods were employed to correct for biases, our findings require validation in future, larger, and more balanced sample cohorts. Critically, we were unable to quantitatively analyze detailed dietary diaries for all participants and include diet as a covariate, which is a key aspect to address in future studies.

Our findings suggest several avenues for future research: utilize germ-free animal models colonized with fecal microbiota from ASD and neurotypical children to directly test whether the “biofilm hypothesis” leads to impaired intestinal barrier function, neuroinflammation, and ASD-like behaviors. This is the gold standard for validating functional hypotheses。Combine metagenomic data with metabolomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to paint a more complete picture of the “microbiota-gut-brain axis”65,68. For example, this approach could further validate the metabolite changes observed in our study or explore other potential biomarkers, such as the GABA/glutamate ratio71, to confirm the real-world biological effects of functional pathways like ABC transporters. Based on the observed depletion of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium72,73, more targeted next-generation probiotic or symbiotic interventions can be designed59. Furthermore, if the “biofilm hypothesis” is confirmed, developing strategies to disrupt or inhibit harmful biofilm formation could become a revolutionary approach for treating ASD-related gastrointestinal issues.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data reported in this paper contain sensitive human genetic information and are therefore not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC), Genome Sequence Archive for Human (GSA-Human), under a controlled-access policy. The accession number for this project is PRJCA043657. The application procedure and requirements for data access are detailed in the official GSA-Human documentation, which can be accessed at: [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/document/GSA-Human_Request_Guide_for_Users_us.pdf].

References

Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G. & Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 392, 508–520 (2018).

Maenner, M. J. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 72(No. SS-2), 1–14 (2023).

Finegold, S. M., Downes, J. & Summanen, P. H. Microbiology of regressive autism. Anaerobe 18(2), 260–262 (2012).

Kang, D. W. et al. Reduced incidence of prevotella and other fermenters in intestinal microflora of autistic children. PLoS ONE 8(7), e68322 (2013).

Song, Y., Liu, C. & Finegold, S. M. Real-time PCR quantitation of clostridia in feces of autistic children. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70(11), 6459–6465 (2004).

Koh, A., De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P. & Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 165(6), 1332–1345 (2016).

Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A. & Frozza, R. L. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 25 (2020).

Plaza-Díaz, J. et al. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with and without mental regression is associated with changes in the fecal microbiota. Nutrients 11(2), 337 (2019).

Xie, X. et al. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 15(6), 996–1007 (2022).

Cao, X. et al. Dysbiotic Gut microbiota and dysregulation of cytokine profile in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 15, 635925 (2021).

Ye, F. et al. Comparison of gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorders and neurotypical boys in China: A case-control study. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 6(2), 120–126 (2021).

Goodrich, J. K. et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 159(4), 789–799 (2014).

Sandin, S. et al. The familial risk of autism. JAMA 311(17), 1770–1777 (2014).

Sandin, S. et al. The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA 318(12), 1182–1184 (2017).

Wang, L. W., Tancredi, D. J. & Thomas, D. W. The prevalence of gastrointestinal problems in children across the United States with autism spectrum disorders from families with multiple affected members. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 32(5), 351–360 (2011).

Zuffa, S. et al. Early-life differences in the gut microbiota composition and functionality of infants at elevated likelihood of developing autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 13(1), 257 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Effect of maternal diet on gut bacteria and autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 19, 1623576 (2025).

Kurokawa, S. et al. A comparative study on dietary diversity and gut microbial diversity in children with autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, their neurotypical siblings, and non-related neurotypical volunteers: a cross-sectional study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 65(9), 1184–1195 (2024).

Abuljadayel, D. et al. Gut microbiota of children with autism spectrum disorder and healthy siblings: A comparative study. Exp. Ther. Med. 28(5), 430 (2024).

Yap, C. X. et al. Autism-related dietary preferences mediate autism-gut microbiome associations. Cell 184(24), 5916–5931 (2021).

Kultima, J. R. et al. MOCAT2: A metagenomic assembly, annotation and profiling framework. Bioinformatics 32(16), 2520–2523 (2016).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17(1), 10–12 (2011).

Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A. & Biggs, P. J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 11, 1–6 (2010).

Gu, S., Fang, L. & Xun, Xu. Using SOAPaligner for short reads alignment. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 44(1), 11–11 (2013).

Xie, Y. et al. SOAPdenovo-Trans: De novo transcriptome assembly with short RNA-Seq reads. Bioinformatics 30(12), 1660–1666 (2014).

Zhu, W. Improvement of ab initio methods of gene prediction in genomic and metagenomic sequences. Georgia Institute of Technology. (2010).

Huang, Y. et al. CD-HIT Suite: A web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26(5), 680–682 (2010).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12(1), 59–60 (2015).

Chen, L. et al. VFDB: A reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 33(suppl_1), D325–D328 (2005).

Liu, B. & Pop, M. ARDB—Antibiotic resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(suppl_1), D443–D447 (2009).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25(14), 1754–1760 (2009).

Truong, D. T. et al. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat. Methods 12(10), 902–903 (2015).

Franzosa, E. A. et al. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nat. Methods 15(11), 962–968 (2018).

Caspi, R. et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes-a 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D445–D453 (2020).

Oksanen, J. et al. “Package ‘vegan’.” Community Ecology Package, Version 2.9. 1–295 (2013).

Thouverai, E. et al. Rarefy: Rarefaction Method. 1–22. (2020).

Gibert, C. & Escarguel, G. PER-SIMPER—A new tool for inferring community assembly processes from taxon occurrences. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28(3), 374–385 (2019).

Anderson, M. J. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Wiley statsref: Statistics Reference Online. 1–15 (2014),

Love, M., Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential analysis of count data–the DESeq2 package. Genome Biol. 15(550), 10–1186 (2014).

Chang, F., He, S. & Dang, C. Assisted selection of biomarkers by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) in microbiome data. JoVE J. Vis. Exp. 183, e61715 (2022).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17(11), e1009442 (2021).

Luo, W. et al. GAGE: Generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinform. 10, 1–17 (2009).

Luo, W. & Brouwer, C. Pathview: An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 29(14), 1830–1831 (2013).

Ahmed, S. A. et al. Study of the gut microbiome profile in children with autism spectrum disorder: A single tertiary hospital experience. J. Mol. Neurosci. 70(6), 887–896 (2020).

Kasahara, K., Kerby, R.L., Cross, T.L., Everhart, J., Kay, C., Bolling, B.W., Bäckhed, F. & Rey, F.E. Gut microbiota and diet matrix modulate the effects of the flavonoid quercetin on atherosclerosis. Res. Sq. [Preprint]. rs.3.rs-2431147. (2023).

Argou-Cardozo, I. & Zeidán-Chuliá, F. Clostridium bacteria and autism spectrum conditions: A systematic review and hypothetical contribution of environmental glyphosate levels. Med. Sci. 6(2), 29 (2018).

Tomova, A. et al. Gastrointestinal microbiota in children with autism in Slovakia. Physiol. Behav. 138, 179–187 (2015).

Pequegnat, B. & Monteiro, M. A. Carbohydrate scaffolds for the study of the autism-associated bacterium Clostridium bolteae. Curr. Med. Chem. 26(35), 6341–6348 (2019).

Feng, P., Zhao, S., Zhang, Y. & Li, E. A review of probiotics in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: Perspectives from the gut-brain axis. Front. Microbiol. 16(14), 1123462 (2023).

Huang, R. Y. et al. Metagenome-wide association study of the alterations in the intestinal microbiome composition of ankylosing spondylitis patients and the effect of traditional and herbal treatment. J. Med. Microbiol. 69(6), 797–805 (2020).

Taniya, M. A. et al. Role of gut microbiome in autism spectrum disorder and its therapeutic regulation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 915701 (2022).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(D1), D672–D677 (2025).

De Sales-Millán, A. et al. Comprehensive analysis of gut microbiota composition and functional metabolism in children with autism spectrum disorder and neurotypical children: Implications for sex-based differences and metabolic dysregulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(12), 6701 (2024).

El-Ansary, A., Bhat, R. S. & Zayed, N. Gut microbiome and sex bias in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 7(1), 22–31 (2020).

Wan, Y., Qi, Su. & Ng, S. C. New insights on gut microbiome and autism. Trends Mol. Med. 30(12), 1100–1102 (2024).

Kadiyska, T. et al. Age-dependent gut microbiome dysbiosis in autism spectrum disorder and the role of key bacterial ratios. Nutrients 17(11), 1775 (2025).

Al-Beltagi, M. et al. Metabolomic changes in children with autism. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 13(2), 92737 (2024).

Sadeghpour, F. H. & Hu, H. Bifidobacterium: Host–microbiome interaction and mechanism of action in preventing common gut-microbiota-associated complications in preterm infants: A narrative review. Nutrients 15(3), 709 (2023).

Mehra, A. et al. Gut microbiota and Autism spectrum disorder: From pathogenesis to potential therapeutic perspectives. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 13(2), 135 (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. The gut core microbial species Bifidobacterium longum: Colonization, mechanisms, and health benefits. Microbiol. Res. 290, 127966 (2025).

Andriantsoanirina, V. et al. Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium breve isolates from preterm and full term neonates: Comparison of cell surface properties. Anaerobe 28, 212–215 (2014).

Yu, R. et al. The complex interplay between autism spectrum disorder and gut microbiota in children: A comprehensive review. Behav. Brain Res. 473, 115177 (2024).

Hughes, H. K., Rose, D. & Ashwood, P. The gut microbiota and dysbiosis in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 18(11), 81 (2018).

Bhusri, B. et al. Characterization of gut microbiota on gender and age groups bias in Thai patients with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 2587 (2025).

Peralta-Marzal, L. N. et al. The impact of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(18), 10052 (2021).

Chang, X. et al. Gut microbiome and serum amino acid metabolome alterations in autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4037 (2024).

Mills, S. et al. Efficacy of Bifidobacterium longum alone or in multi-strain probiotic formulations during early life and beyond. Gut Microbes 15(1), 2186098 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. The identification of metabolites from gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorder via network pharmacology. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 31765 (2025).

Coretti, L. et al. Sex-related alterations of gut microbiota composition in the BTBR mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 45356 (2017).

Hokanson, K. C. et al. Sex shapes gut–microbiota–brain communication and disease. Trends Microbiol. 32(2), 151–161 (2024).

Wang, Dilong, et al. Gut microbial GABA imbalance emerges as a metabolic signature in mild autism spectrum disorder linked to overrepresented Escherichia. Cell Rep. Med. 6(1). (2025).

Dargenio, V. N. et al. Impact of Bifidobacterium longum Subspecies infantis on pediatric gut health and nutrition: Current evidence and future directions. Nutrients 16(20), 3510 (2024).

Esaiassen, E. et al. Bifidobacterium bacteremia: clinical characteristics and a genomic approach to assess pathogenicity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55(7), 2234–2248 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this trial as well as their families.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFC2704300 and 2021ZD0201300], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [32400532], Xiamen Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 3502Z202372073), the Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project [2024GGB18], the Fujian Science and Technology Program Guiding Project [2025D022] and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China [Grant No. 2025J08313].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qun Chen: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Jing Xu: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Jingjing Yang: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Xiaoya Qin: Resources, Validation. Jiajun Fan: Resources, Validation. Hailin Ke: Investigation, Resources. Ziyue Yang: Investigation, Resources. Wenjie Zheng: Visualization. Xingyu Li: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. Lihong Huang: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. Wanshan Ning: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, approved the final version for submission, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine (Approval Number: LW 2024-005). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to inclusion in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Xu, J., Yang, J. et al. Gut microbiota analysis in children with autism spectrum disorder and their family members. Sci Rep 15, 44282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27822-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27822-z