Abstract

Emerging migratory pests pose major challenges to farmers, yet management options remain limited beyond pesticide use. These migratory pests, such as locusts and other migratory grasshoppers, have high energy demands relative to their need for nitrogen and other nutrients. Laboratory and field-cage research has shown that feeding on high-nitrogen plants can suppress the growth, survival, and migration, because these insects struggle to meet energy requirements (carbohydrates and lipids) while contending with the costs of excess nitrogen intake. While soil amendments have been tested in field cages, their effect on migratory pest populations in open-air agroecosystems has not been examined. Here, working with 100 farmers, we present the first large-scale demonstration that soil amendments can reduce migratory pest abundance and improve crop yields under field conditions. Our open-air experiment reveals that even localized increases in plant nitrogen, at scales relevant to agricultural fields, can decrease plant palatability and abundance of leaf-chewing migratory insects in free-ranging populations. This study advances our understanding of the nutritional ecology of migratory herbivores and provides a promising addition to sustainable pest management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migratory pests, such as locusts and armyworms, can devastate crops and food security and are particularly challenging to manage because they traverse extended landscapes and require many actors1. Nevertheless, by using pest biology, agriculturists can create bottom-up conditions that decrease pest outbreaks. Locusts and other migratory grasshoppers have high energy demands and field populations overwhelmingly respond positively to plants with low protein and high energy (carbohydrates and lipids) contents2,3. Diets with a low protein to energy ratio have been shown to increase growth rate, survival, and reproduction for Oedaleus asiaticus in China4, Oedaleus senegalensis in West Africa5,6,7, Schistocerca cancellata in South America3,8, and Chortoicetes terminifera Australia9,10,11. Across these diverse regions, energy-rich diets enable locusts to accumulate the large energy stores needed for migration without the harmful effects of overeating protein8,12,13. In migratory locusts, Locusta migratoria, flight increases carbohydrate but not protein intake and locusts eating carbohydrate-biased diets fly for longer times than locusts eating balanced or protein-biased diets13,37.

Translating to landscapes, low nitrogen environments tend to produce plants with low protein contents because most nitrogen in plants is found in the form of protein. Field surveys of locust species in Australia, China, and West Africa from hectare to continental scales have shown that locust outbreaks tend to be associated with these low (and not high) nitrogen environments4,5,7,9,11,14. This body of research suggests that manipulating plant nitrogen content through soil amendments could suppress migratory pests, but this hypothesis has not been tested at agricultural scales.

Potential concerns of using soil amendments as a management strategy for migratory pests include: (1) the actual effectiveness at the field scale in reducing pest abundance given their high mobility, and (2) the risk of increasing other herbivore pest populations by raising crop nitrogen content15,16. Generalist herbivores, including locusts and other grasshoppers, can regulate their nutrient intake by choosing among different plants17. Thus, it was unclear whether soil amendments at the field crop level would be effective in dampening abundance of free-roaming migratory pests, or whether influx from surrounding untreated landscape would negate this effect. Similarly, increasing plant nitrogen might attract other pests, potentially negating any yield gains from pest suppression.

In this study, we tested the effect of soil amendments on the abundance of Senegalese grasshoppers Oedaleus senegalensis (Krauss, 1877) and millet production at the village scale in central Senegal. Senegalese grasshoppers are widely distributed from West Africa to India. They were not considered a pest before major outbreaks began in the mid to late twentieth century, likely in response to land use, land cover, and climate change18. Now, as one of the main cereal crop pests of the Sahel, they can cause devastating crop losses of 20–90% for millet, sorghum, rice, and other cereal crops18. Locusts are grasshoppers in the family Acrididae that form economically damaging migratory swarms when at high density19. Senegalese grasshoppers are a non-model locust in that they exhibit moderate locust-like traits, including darker outbreak morphs and loose migratory swarms20.

We worked with 100 farmers from two village areas, Gossas and Gniby, in central Senegal. Each farmer delineated one hectare of their millet for control and the other for inorganic fertilizer (one application of NPK (15-10-10) followed by two applications of urea (46-0-0)). This approach with each farmer having a control and treatment field helped account for small variations in cultivation practices between farmers and allowed each farmer to compare the outcome of the treatment directly in their own fields. We then surveyed the control and treated fields for pest abundance and damage three times throughout the growing season. We recorded the millet yield for each field during harvest time at the end of the growing season.

Results

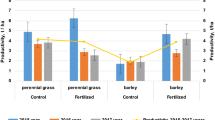

The fertilizer treatment successfully decreased pest abundance and damage, and increased millet yield (Fig. 1; statistics in the Supplementary Information online in Tables S1, S2, and S3). Locust abundance was high in all fields during the first survey, prior to the fertilizer treatment, but decreased further in treated fields than control fields during the second and third surveys, which took place during and after fertilization, respectively (Figs. 1A, B, S1 and S2; statistics in Supplement Table S1). For nearly all farmer participants, fertilizer decreased pest abundance relative to their control field (Supplement Fig. S3).

Soil amendments decreased locust abundance (A, B) and damage (C, D), and increased millet yield (E, F). The left column shows raw individual data points. Grey points are a pre-treatment survey, followed by survey 2 and survey 3, all of which recorded insect abundance and damage in control and treated fields. Black points are control fields and green points are fertilized fields. The initial survey (pretreatment survey 1) was completed before the fertilizer treatment was initiated, the second survey was carried out after the initial 1–2 fertilizer doses were applied, and the third survey was completed after all fertilizer doses had been completed. Yield was measured once, during the single harvest season in autumn. The right column shows the estimated marginal means and standard error for all surveys post treatment. The statistical tables and additional visualizations of these data are in the Supplementary Information: abundance (Table S1, Figs. S1, S2, and S3), damage (Table S2), yield (Table S3).

There was no relationship between locust count and percent of green vegetation ground cover or humidity at the time of sampling (Supplement Figs. S4 and S5; statistics are in the figure legends). There was a small effect of ambient temperature during the time of surveying and locust count (Supplement Fig. S6; statistics are in the figure legend).

Discussion

We found that the fertilizer treatment led to a positive outcome for both migratory pest control and millet yield (Fig. 1). This open-air agroecosystem experiment corroborates earlier lab and field cage studies where locusts were contained to small areas4,5,6,7, despite potential confounding factors. For example, the highly mobile pests could have spilled over into the treatment fields from the untreated surrounding landscape and/or the fertilizer treatment could have attracted other pests. If either of these had occurred substantially, it would have nullified the observed effects of fertilizer on locust count, damage, and yield. However, the treatment had a significant effect on all three, demonstrating that soil amendments can serve as a viable tool for migratory pest management.

For leaf chewing herbivores, including grasshoppers and locusts, protein (p) and carbohydrates (c) make up the majority of nutrients consumed; thus, foraging is highly attuned to balancing the two17. Plants with too low p:c ratios limit herbivore growth because an individual cannot eat enough of the low p:c food to meet their protein requirement. Conversely, plants with too high p:c ratios also reduce growth and survival because herbivores quickly meet their protein demand and then face the negative consequences of overeating protein (reviewed in Simpson and Raubenheimer 201217 and Cease 20242). Overeating protein has well-documented deleterious effects, including lifespan reduction across many taxa21,22. For Senegalese grasshoppers, fertilized millet leaves exhibit especially high p:c ratios relative to their intake targets. Unfertilized millet leaves in central Senegal have roughly 1.7p:1c; fertilizer application increases this to about 3p:1c6. In contrast, Senegalese grasshopper intake targets range from 1p:1.3c to 1p:1.6c depending on season and generation5,23,24. Earlier surveys show that Senegalese grasshoppers are most abundant in landscapes harboring low p:c plants matching their preferred intake5,7.

This pattern aligns with small-scale lab studies using artificial diets of varying p:c ratios and field-cage studies confining Senegalese grasshoppers to fertilized or unfertilized millet plots, where high p:c diets generally decrease growth, survival, and reproduction5,6. Our study extends these findings by demonstrating that soil amendments at agroecosystem scales can suppress migratory pest abundance and damage in open-air field conditions. For locusts, long-distance migration increases carbohydrate, but not protein, demands13,37. This heightened carbohydrate requirement likely explains their poor performance on protein-biased diets, making soil amendments that elevate plant p:c an effective management strategy to suppress pests and increase yield.

It is possible that elevating plant nitrogen could attract other nitrogen-limited pests. However, farmer participants did not report outbreaks of other pests or diseases, and yield was more than twice as high on average in fertilized fields.

This research was part of the project “Communities for Sustainable Agriculture”, or Bay Sa Waar in Wolof, the primary language spoken in Senegal. Bay Sa Waar is a phrase that encourages farmers to “farm their part”, that is, do their part to engage in the monitoring and prevention of locust and grasshopper outbreaks. The program grew from earlier smaller-scale research projects in the region5,7,25. Upon seeing clear correlations between land use, soil and plant nutrients, and Senegalese grasshopper abundance, original farmer participants recommended scaling up, leading to the current study.

Farmers are often considered passive recipients of migratory pests. In contrast, this study shows that communities can actively contribute to migratory pest management using soil amendments. Chemical fertilizers provided a proof-of-concept here, but their high cost and environmental impact generally limit widespread use in the region. Ongoing research is exploring how compost might similarly suppress migratory pests while improving soil organic matter. Although decomposing compost may attract soil-dwelling pests, thus it will be important to assess whether such drawbacks outweigh benefits in this context26. In central Senegal and similar Sahelian regions, increasing demand for arable land, unsustainable cultivation practices, and overgrazing degrade soil quality and crop yield while promoting Senegalese grasshopper outbreaks18. Therefore, community-based programs enhancing long-term soil fertility are likely to improve food security and livelihoods via multiple pathways: suppressing migratory pests, decreasing pesticide dependence, and increasing yields.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that applying pest nutritional ecology can enhance sustainable management by offering a practical, scalable tool that could be coordinated across regions as part of area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) programs. By improving soils to grow protein-biased plants that exploit the high energy demands of migratory pests like the Senegalese grasshopper, farmers can contribute to long-term population suppression across regions while reducing reliance on chemical controls.

Methods

We worked with farmers from two areas, Gossas and Gniby, in central Senegal, which is characterized by a Sahelo-Sudanian climate (Figs. 2, 3). This area is mainly open savanna and contains a patchy distribution of shrubs and trees, pseudo-shrubby steppes, and some remnants of open forests27. Agriculture in Senegal is primarily rainfed with the main crops being planted with the onset of the rains around June or July and harvested in approximately October or November28. From November to May, the region persists largely parched and dusty. Gossas is in the Fatick Region, Department of Gossas, which has an annual precipitation of 400–600 mm29. Gniby is in the Region and Department of Kaffrine, which received an average annual rainfall of 700 mm between 2016 and 202130. The region’s average temperature is 27 °C during the dry season and 29 °C in the rainy season28. Senegalese grasshoppers migrate seasonally, following the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) north with the rains up to 170–180°N and back south to 110–120°N at the end of the rainy season18,31,32. This species typically has three generations (G1 to G3) annually, with G1 hatching roughly between June and August, and the adults from G3 lasting through roughly October or November18,31. G1 and G2 generally hatch and develop in the southern part of its range. Gossas and Gniby lie in this core area, where grasshopper infestations are frequent. As the rain front moves north, G1 and G2 migrate northward due to increasing humidity in the south, while G3 returns south at season’s end. For the Gossas and Gniby, young to mid-stage crops planted at the rainy season start are vulnerable to G1 and G2. In addition, G3 often returns when cereal crops have seeds in the soft milky stage and they are vulnerable to attacks from Senegalese grasshopper adults24. G3 lays eggs that diapause through the long dry season.

The location of the two village areas in Senegal. The map was generated in R version 4.4.1 (https://cloud.r-project.org/) using the packages ggplot2, sf, and rnaturalearth. Basemap data are from Natural Earth (public domain; available at www.naturalearthdata.com).

Early discussions with farmers about the project in an unsown field before the rainy season (A). Senegalese grasshopper in the foreground and a fallow field in the background (B). The Senegalese Plant Protection Directorate in Nganda (C). A participant’s millet field early (D) and late (E) in the growing season. A. Cease photo credit (A, B, C); M. Touré photo credit (D, E).

Participants were provided with improved millet seed (Souna 3) for two hectares and fertilizer for one hectare, following recommendations by the Senegalese Agricultural Research Institute (ISRA). Fertilizer was applied in three stages: (1) 15 days after germination, 150 kg/ha of NPK (15-10-10) fertilizer was applied, (2) at bolting, 30–35 days post-germination, 75 kg/ha of urea (46-0-0) was applied, and (3) at flowering, 60–65 days post-germination, another 75 kg/ha urea application. Both hectares were cultivated according to farmers’ typical practices: plowing the dry land before the rains start, planting millet seeds in rows about one week after first rains, and weeding in between the rows every few weeks using livestock or hand-drawn plows.

We surveyed O. senegalensis abundance three times across all fields. The first survey occurred from September 2–8, 2019, about 20 days after the initial rainfall and before fertilizer application. The second survey took place from September 26 to October 2, during millet tillering after 1–2 fertilizer applications. The third and final survey was October 15–23 during heading and after all fertilizer applications.

Adult grasshopper and locust abundance was measured by counting individuals that flew in front of the surveyor while walking a 100 m transect. Each transect was walked 100 times per field per survey; the average number of adults was calculated per square meter. Nymph abundance was estimated using one-meter square plots: the surveyor delimited a square a few steps head, then approached gradually to count all the grasshopper and locust nymphs that hopped out, then carefully combed through the vegetation within the square. One hundred randomly selecting squares were sampled per field and survey, spaced several meters apart, and the average number of nymphs per square meter calculated. Adult and nymph densities per 100 square meters were then summed.

We determined the proportion of O. senegalensis in the local grasshopper population by sweep netting to collect grasshopper adults and nymphs in control and fertilized millet fields during each survey. This species made up most of the grasshopper and locust community for Gossas (85 + / − 2%) and Gniby (90 + / − 2%). These proportions were consistent across control and fertilized fields, and throughout the growing season. We multiplied abundance data from Gossas by 0.85 and from Gniby by 0.90 to calculate number of O. senegalensis per 100 square meters.

Due to time constraints, millet damage by grasshopper pests was assessed on a subset of 10 fertilized and 10 control fields. In each field, a 10-m path was delineated along a millet row. We then carefully counted the total number of tillers and leaves along the path as well as the percent of each leaf eaten by grasshoppers or locusts. We repeated this assessment transect 25 times for each field and survey.

We recorded date, time of day, percent green vegetation ground cover, temperature, and relative humidity for each field surveyed (Figs. S4, S5, S6).

All farmer participants were invited to a standardized millet harvesting and threshing process to measure yield. Harvesting equipment, including a thresher, was provided for each village. Millet seeds were bagged and weighed, with total kilograms harvested recorded for each farmer’s control and fertilized millet hectare.

We held closing meetings to share the results with the communities and get their feedback on improvements, focusing on composting as an alternative soil amendment.

We used generalized linear mixed models (family: tweedie, link: log) to assess how different fertilization treatments impacted millet yield and the abundance of O. senegalensis, while including random effects to account for variability between farmers and village areas. Model selection was guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), ensuring we chose the most parsimonious model that fit the data. To measure treatment effects, we generated parametric estimates and estimated marginal means, which were compared across models. We also conducted diagnostic checks to assess assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and overall model fit. Additional figures and statistical tables are available in the supplementary information. Analyses were conducted in R using mgcv33 for model fitting, gratia34 for diagnostics, and the tidyverse suite35 for data handling and visualization. All code, data, and package information are freely available at:36

Data availability

Scripts and data available at36

References

Ries, M. W. et al. Global perspectives and transdisciplinary opportunities for locust and grasshopper pest management and research. J. Orthoptera Res. 33, 169–216 (2024).

Cease, A. J. How nutrients mediate the impacts of global change on locust outbreaks. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 69, 527–550 (2024).

Cease, A. J. et al. Field bands of marching locust juveniles show carbohydrate, not protein, limitation. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cris.2023.100069 (2023).

Cease, A. J. et al. Heavy livestock grazing promotes locust outbreaks by lowering plant nitrogen content. Science 335, 467–469 (2012).

Le Gall, M. et al. Linking land use and the nutritional ecology of herbivores: A case study with the Senegalese locust. Funct. Ecol. 34, 167–181 (2020).

Le Gall, M., Word, M. L., Thompson, N., Beye, A. & Cease, A. J. Nitrogen fertilizer decreases survival and reproduction of female locusts by increasing plant protein to carbohydrate ratio. J. Anim. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13288 (2020).

Word, M. L. et al. Soil-targeted interventions could alleviate locust and grasshopper pest pressure in West Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 663, 632–643 (2019).

Talal, S. et al. Plant carbohydrate content limits performance and lipid accumulation of an outbreaking herbivore. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 287, 2–9 (2020).

Lawton, D., Waters, C., Le Gall, M. & Cease, A. Woody vegetation remnants within pastures influence locust distribution: Testing bottom-up and top-down control. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 296, 1–10 (2020).

Lawton, D., Le Gall, M., Waters, C. & Cease, A. J. Mismatched diets: Defining the nutritional landscape of grasshopper communities in a variable environment. Ecosphere 12, 1–16 (2021).

Lawton, D. et al. Exploring nutrient availability and herbivorous insect population dynamics across multiple scales. Oikos https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.11189 (2025).

Talal, S. et al. High carbohydrate diet ingestion increases post-meal lipid synthesis and drives respiratory exchange ratios above 1. J. Exp. Biol. 224, 1–6 (2021).

Talal, S., Parmar, S., Osgood, G. M., Harrison, J. F. & Cease, A. J. High carbohydrate consumption increases lipid storage and promotes migratory flight in locusts. J. Exp. Biol. 226, 1–6 (2023).

Le Gall, M., Overson, R. & Cease, A. J. A global review on locusts (Orthoptera: Acrididae) and their interactions with livestock grazing practices. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1–24 (2019).

White, T. C. R. The inadequate environment: Nitrogen and the abundance of animals (Springer-Verlag, 1993).

Mattson, W. J. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1, 119–161 (1980).

Simpson, S. J. & Raubenheimer, D. The nature of nutrition: A unifying framework from animal adaptation to human obesity (Princeton University Press, 2012).

Le Gall, M. et al. Chapter 4 - Senegalese grasshopper—A major pest of the Sahel. In Biological and environmental hazards, risks, and disasters 2nd edn (eds Sivanpillai, R. & Shroder, J. F.) 77–96 (Elsevier, 2023).

Cullen, D. A. et al. From molecules to management: Mechanisms and consequences of locust phase polyphenism. in Advances in Insect Physiology vol. 53 167–285 (Elsevier, 2017).

Song, H. Density-dependent phase polyphenism in non-model locusts. Psyche: J. Entomol. 2011, 1–16 (2011).

Le Couteur, D. G. et al. The impact of low-protein high-carbohydrate diets on aging and lifespan. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1237–1252 (2016).

Moatt, J. P., Savola, E., Regan, J. C., Nussey, D. H. & Walling, C. A. Lifespan extension via dietary restriction: Time to reconsider the evolutionary mechanisms?. BioEssays 42, 1900241 (2020).

Le Gall, M., Word, M. L., Beye, A. & Cease, A. J. Physiological status is a stronger predictor of nutrient selection than ambient plant nutrient content for a wild herbivore. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 1, 100004 (2021).

Le Gall, M., Beye, A., Diallo, M. & Cease, A. J. Generational variation in nutrient regulation for an outbreaking herbivore. Oikos 2022, 1–15 (2022).

Toure, M., Ndiaye, M. & Diongue, A. Effect of cultural techniques: Rotation and fallow on the distribution of Oedaleus senegalensis (Krauss, 1877) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) in Senegal. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 8, 5634–5638 (2013).

Nyamwasa, I. et al. Overlooked side effects of organic farming inputs attract soil insect crop pests. Ecol. Appl. 30, e02084 (2020).

Mbow, C., Mertz, O., Diouf, A., Rasmussen, K. & Reenberg, A. The history of environmental change and adaptation in eastern Saloum–Senegal—Driving forces and perceptions. Glob. Planet. Chang. 64, 210–221 (2008).

D’Alessandro, S., Fall, A. A., Grey, G., Simpkin, S. & Wane, A. Senegal. Agricultural sector risk assessment. (2015).

ANSD. Agence Nationale de La Statistique et de La Démographie, Situation Economique et Sociale de La Région de Fatick, Édition 2019. (2021).

ANSD. Agence Nationale de La Statistique et de La Démographie, Situation Economique et Sociale de La Région de Kaffrine Ed. 2020/2021. (2023).

Maiga, I. H., Lecoq, M. & Kooyman, C. Ecology and management of the Senegalese grasshopper Oedaleus senegalensis (Krauss 1877) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) in West Africa: Review and prospects. Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.) 44, 271–288 (2008).

Launois, M. An ecological model for the study of the grasshopper Oedaleus senegalensis in West Africa. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 287, 345–355 (1979).

Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat Methodol. 73, 3–36 (2011).

Simpson, G. gratia: Graceful ggplot-based graphics and other functions for GAMs fitted using mgcv (Version 0.10.0) [R package]. https://gavinsimpson.github.io/gratia/ (2024).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Touré, M., Fall, A., Burnham, A., Beye, A., Badiane, S., Lawton, D., & Cease, A. Code for Soil Amendments Suppress Migratory Pests andEnhance Yields. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17547461. (2025)

Arianne J. Cease, Stav Talal, Geoffrey Osgood, Tree Pulver, Sydney Millerwise, Rick P. Overson, Jon F. Harrison; Energetic constraints on multi-dayflights in migratory locusts. J. Exp. Biol.. jeb.251191. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.251191. (2025)

Acknowledgements

We thank the farmers in Gniby and Gossas, Senegal who participated in this project, as well as the broader communities of the Kaffrine and Fatick regions of Senegal for welcoming researchers into their communities and sharing details of their locust experiences. Thanks to La Direction de la Protection des Végétaux (DPV), Senegal, and the Nganda DPV Phytosanitary base (Idrissa Biaye, Ismaela Thiow, Ibrahim Sadio, Makam Cisse, Manga and Papa Ndiaye) for their collaboration and assistance on this project. We thank Yeneneh Belayneh for his encouragement and feedback on this project, Gnima Konté for data entry, Amadou Sow, Mouhamadane Fall, and Fatou Bintou Sarr for their technical assistance, Makhtar Fall and Dame Wade for leading the mission’s staff into the field, and Rick Overson, Marion Le Gall, Jon Harrison, Syeda Mehreen Tahir, and Holly Nelson for their assistance with samples and helpful discussions. In the US, the authors recognize that ASU’s Tempe campus resides on the ancestral lands of the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) peoples, whose stewardship of these lands allows us to be here today. This work was funded by the National Science Foundation, United States [IOS-1942054, DBI 2021795] and the U.S. Agency for International Development [720FDA18GR00100]. This work was a project by the Global Locust Initiative Laboratory, Arizona State University.

Funding

U.S. Agency for International Development, 720FDA18GR00100, National Science Foundation, United States, IOS-1942054, DBI 2021795.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C., M.T., and A. Beye designed the study. Fieldwork was conducted by M.T., A.F., A.B., A.B., S.K.B., and A.C. Sample processing was performed by M.T. and A.C. The original paper draft was prepared by A.C. and M.T. Edits were provided by A.C., M.T., D.L. Statistical modeling was conducted by D.L. Figures were prepared by A.C. and D.L. Funding was acquired by A.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent from all participants was obtained following a protocol approved by Arizona State University’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent of the people pictured in Fig. 3 was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Touré, M., Fall, A., Burnham, A. et al. Soil amendments suppress migratory pests and enhance yields. Sci Rep 16, 646 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27884-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27884-z