Abstract

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) has its effects through biologically-active peptides, the angiotensins (Ang). The angiotensinogen-derived precursor, Ang I, is cleaved either to proinflammatory Ang II, which increases blood pressure or to Ang 1–7, which has opposite effects to Ang II. Here, we show that Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) and Tannerella forsythia (Tf), endogenous oral pathogens, direct the RAS to generate Ang 1–7 through the actions of the endopeptidases O PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively. The thermophilic PepOs metalloproteases preferred large hydrophobic amino acids at the carbonyl terminus of scissile peptide bonds (P1′ position), and TfPepO, in contrast to all known homologous proteases, hydrolyzed substrates distant to both termini. The crystal structures revealed exceptionally wide entrances to the catalytic cleft, which explains the unique properties of TfPepO. Multiple immunoassays showed that PepOs attached to bacterial cell surfaces are released in outer membrane vesicles. Moreover, PepO was responsible for Ang I hydrolysis by Pg and Tf. Finally, PepO deletion reduced only the virulence of Tf using the Galleria mellonella model. Thus, our data show that PepOs are the only proteases of Pg and Tf, which may modulate RAS through AngI hydrolysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human body has many essential systems, one of which is the hormone–renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which regulates blood pressure and water and electrolyte balance. The two main components of the RAS system are a peptide hormone, angiotensin II (Ang II), and renin, an aspartic protease produced by kidney granular cells that hydrolyzes circulating angiotensinogen to produce angiotensin I (Ang I)1. Ang I is converted to other angiotensins during further processing by two pathways. The first involves the removal of two amino acids from the C-terminus of Ang I by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), resulting in the formation of Ang II. Through interaction with the AT1 receptor (AT1R), Ang II has potent proinflammatory and vasoconstrictive effects and also increases oxidative stress, hypertrophy, and cell proliferation. The second pathway, which includes ACE II and a neutral endopeptidase, neprilysin, generates angiotensin 1–7 (Ang 1–7) directly from Ang I or through the intermediate molecule angiotensin 1–9 (Ang 1–9). In contrast to Ang II, Ang 1–7 has anti-inflammatory effects, reduces oxidative stress, and reduces blood pressure through interaction with the Mas receptor (MasR)1,2,3. Dysregulation of RAS may result in cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension4, and other systemic conditions, such as atherosclerosis5 and diabetes6. In addition to having systemic effects, the components of RAS are also locally expressed in many tissues, such as periodontal tissues7, where the mRNA expression of all the critical elements of this system, the presence of angiotensins8 and the interaction of Ang II with AT1R have been shown9.

Periodontitis, or periodontal disease, involves damage to the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth and affects up to 20% of the world’s adult population in its severe forms10. If left untreated, this disease not only leads to tooth loss, but also contributes to the progression and/or development of systemic diseases, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer11. Moreover, it is responsible for significant health and economic burdens; in 2018 alone, the costs related to periodontitis were estimated to be USD 154.06 billion in the USA and EUR 158.64 billion in the European Union12. Periodontitis has a complex, multifactorial etiology, but the critical event leading to the development of the disease is the disruption of the homeostasis of the oral microflora in subgingival plaque13. Plaque becomes pathogenic when the composition of the microbial community changes, such that it contains a larger proportion of gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. This is caused by the colonization of the plaque by so-called “keystone pathogens”, which affect the host response and increase the virulence of the entire community. One such microbe is Porphyromonas gingivalis, which is almost always found together with Treponema denticola and Tannerella forsythia14,15,16. The presence of these three gram-negative anaerobic pathogens, which form a “red complex” of bacteria, is closely associated with both the development of the disease and the severity of its symptoms17,18,19.

A common feature of “red complex” bacteria is the secretion of an array of extracellular proteases. P. gingivalis secretes gingipains R (RgpA, RgpB) and K (Kgp), which are responsible for 85% of the extracellular proteolytic activity of this bacterium, and are involved in nutrient acquisition, help it avoid the innate immunity of the host and have immunomodulatory effects20. T. forsythia secretes, among other substances, six KLIKK proteases (three serine proteases (mirolase, miropsin-1, and miropsin-2) and three metalloproteases (mirolysin, karilysin, and forsilysin)), which share a unique multi-domain structure21. Karilysin and mirolysin are responsible for complement evasion and the inactivation of LL-37, a crucial antimicrobial peptide that is present in the human oral cavity22,23,24. P. gingivalis and T. forsythia also secrete the endopeptidases O (PepOs) PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively25,26. PgPepO is involved in the invasion of host cells25,27 and cleaves big endothelin-1 and Ang I28,29. However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding PgPepO and there have been no studies of the TfPepO protease.

Herein, we report that the periodontopathogens P. gingivalis and T. forsythia impair the functioning of the RAS through the production of single proteases (PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively). We present a thorough biochemical characterization of these proteases, revealing their substrate specificity. Furthermore, we have used X-ray crystallography to solve the structures of these PepOs, which explains the unique properties of TfPepO. Moreover, we have employed a number of methods to show that both PepOs are secretory lipoproteins that attach to the cell surface. Finally, we have used an in vivo model to identify the roles of PepOs in the evasion of host innate immunity by the pathogens.

Results

PgPepO and TfPepO are putative lipoproteins in the M13 family of metalloproteases

PepO proteases from P. gingivalis (PgPepO) and T. forsythia (TfPepO) belong to the MEROPS M13 family of proteases, the progenitor of which is human neprilysin30. PgPepO and TfPepO contain a conserved zinc-binding consensus sequence consisting of two histidine residues and a glutamic acid residue located 25 amino acid residues toward the C-terminus from the main motif (HEXXH…E), and that the first Glu residue has a catalytic function in proteolysis. PgPepO and TfPepO both include signal peptide sequences that are characteristic of secretory lipoproteins that are 22 and 16 amino acid residues in length, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The prediction is based on a hidden Markov model (HMM) that was able to distinguish between lipoproteins (SPaseII-cleaved proteins), other secretory proteins (SPaseI-cleaved proteins), cytoplasmic proteins, and transmembrane proteins. This predictor accurately predicted 96.8% of the lipoproteins, with only 0.3% false positives, in a set of SPaseI-cleaved, cytoplasmic, and transmembrane proteins. The current version of the server used is located at: https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/LipoP-1.0/31. We obtained PgPepO and TfPepO as recombinant proteins using an Escherichia coli expression system. The monomeric tag-free proteins were obtained by affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose, with simultaneous removal of the GST tag using PreScission protease, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Supplementary Fig. S2, S3).

Biochemical characterization

The fluorescent substrate Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH, the amino acid sequence of which is based on the sequence of bradykinin32, has been used to determine the activity of the human M13 metalloproteases (NEP, ECE1, and ECE2). Therefore, we used the same substrate to verify the proteolytic activities of PgPepO and TfPepO. Both proteases hydrolyzed Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH, with Kms of 3 and 3.1 µM, respectively (Fig. 1A), whereas catalytically inactive mutants, with Ala in place of the Glu residue in the catalytic center (PgPepOE527A and TfPepOE515A), showed no activity toward this substrate (Supplementary Fig. S2G, S3F). Therefore, this substrate was used for further biochemical characterization of the PepOs.

Biochemical characterization of PgPepO and TfPepO. (A) The velocity of the reaction (V) was determined for various concentrations of the substrate Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH, and the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) was calculated using a GraphPad Prism macro. (B, C) Effect of pH (B) and temperature (C) on PepO activity. Enzymatic activity was measured at various pHs (B) and temperatures (C). The pH with the highest V (B), and the V at 37 °C (C), which was regarded as 100%. (D) Thermal stability of PgPepO and TfPepO. PepOs were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 30 min, then their enzymatic activities were measured. The activity at 37 °C was set at 100%. (E, F) Effects of inhibitors and reducing agents on the activities of PgPepO and TfPepO. PepOs were incubated with the indicated compounds, and their activities were measured. PepO activity determined at 37 °C in 100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, 0.05% Pluronic F-127 (pH 7.5) was regarded as 100%. Data are mean ± SD (N = 3).

First, we determined the optimum pHs and temperatures for the activities of the enzymes. The PepOs were active at a wide pH range (6–9), and they had their highest activities at pH 8 (PgPepO) and 7 (TfPepO) (Fig. 1B). The PepOs were active throughout the entire temperature range tested (4–100 °C), but had their highest activities at 60 °C (PgPepO) and 50 °C (TfPepO), implying that they are thermophilic enzymes33. However, when incubated alone for 30 min at 70 °C, both lost virtually all their activity (Fig. 1C,D). This discrepancy can be explained by substrate binding to the PepOs increasing their thermostability.

Second, we assessed the effects of various class-specific inhibitors and reducing agents on the activities of the PepOs. Inhibitors of metalloproteases, including dipositive cation chelators (o-Phenanthroline (OF), EDTA, and EGTA) and phosphoramidon, a competitive inhibitor of many metalloproteases (e.g., hNEP, hECE1, and thermolysin), inhibited both PgPepO and TfPepO30. However, inhibitors of serine (TLCK, Pefabloc, leupeptin, and FP-biotin) and cysteine (E-64, leupeptin, TLCK, and iodoacetamide) proteases had no effect on the activities of the PepOs (Fig. 1E). These results are consistent with the conclusions made based on bioinformatic analyses that PgPepO and TfPepO are zinc-dependent metalloproteases. L-cysteine and DTT reduced the activities of both proteases, by 80% and 90%, respectively (Fig. 1E). This inhibition was likely the result of the binding of the free thiol group to the fourth coordination site of the catalytic zinc, which under normal conditions is occupied by a water molecule that is involved in the proteolysis mechanism. Free thiol groups are used not only to develop metalloprotease inhibitors, but also in the so-called “cysteine switch”, one of the mechanisms by which metalloproteases are zymogenic34.

Third, many metalloproteases bind an additional zinc ion, termed the “structural zinc”, or other dipositive ions, such as magnesium or calcium35. Therefore, the effects of these three dipositive cations on the activities of PgPepO and TfPepO were evaluated. Mg2+ and Ca2+ cations had virtually no effect on the activities of the PepOs. In the case of PgPepO, an increase in zinc concentration resulted in a gradual increase in enzyme activity, by 20%, until it reached a maximum at a concentration of 10 µM. However, at concentrations up to 10 µM, zinc ions had virtually no effect on the activity of TfPepO. A further increase in the concentration of zinc ions led gradually to a complete loss of PepOs activity at a concentration of 10 mM (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Finally, because of their important physiologic functions, human enzymes of the M13 family (neprilysin, ECEs, and RAS-related ACE) represent important targets for the development of inhibitors, and such compounds are often used in the treatment of hypertension. Therefore, the effects of daglutril (SLV-306), tiorfan, sacubitrilat (LBQ657) (neprilysin inhibitors), daglutril (SLV-306), human [D-Val22]-big endothelin-1 (16–38) (ECE inhibitors), captopril, and lisinopril (ACE inhibitors) on the activities of PgPepO and TfPepO were evaluated (Fig. 1F). Inhibition was only identified for human [D-Val22]-big endothelin-1 (~ 50% at 100 µM concentration).

Substrate specificity

To determine the substrate specificity of PgPepO and TfPepO, we next tested whether they could hydrolyze various proteins and peptides. The PepOs hydrolyzed three peptide substrates (human big endothelin-1, insulin B-chain, and Ang 1–14), but not the antibacterial peptide LL-37, and only one proteinaceous substrate, α-casein. For peptide substrates, there was no difference in the rate of proteolysis between 1 and 24 h of incubation. Gels from 24 h of incubation are shown to emphasize that the observed hydrolysis is not observed with catalytically inactive PepO mutants and therefore does not originate from the E. coli protease copurified with recombinant PepO. The other evaluated proteins (fibrinogen, fibronectin, hemoglobin, and ferritin) were not cleaved (Fig. 2A, B; Supplementary Fig. S5). PepOs from other bacteria may also participate in the bacterial adhesion to, and invasion of, host cells by binding to human proteins such as plasminogen or fibronectin36. However, neither PgPepO nor TfPepO bound to any proteins that they did not digest (Supplementary Fig. S6). The hydrolysis sites of the cleaved substrates were identified using mass spectrometry and marked on the primary sequence of the substrates (Fig. 2C). We identified six and nine unique hydrolysis sites for PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively, and seven sites that were shared by both enzymes. PgPepO cleaved the substrates near both termini of the substrates, a maximum of eight amino acids away. By contrast, TfPepO hydrolyzed α-casein deep within the polypeptide chain (at least 50 residues from the termini of the protein), indicating the endopeptidase character of this enzyme (Fig. 2C). To identify the motif that is recognized and hydrolyzed by PgPepO and TfPepO, cleavage logos were generated (Fig. 2D). PgPepO and TfPepO were not characterized by restricted substrate specificities and only on the carbonyl side of the scissile peptide bond (P1′) large hydrophobic amino acids were preferred (Fig. 2D). Based on the obtained substrate specificity, it can be assumed that the substrate Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH used for biochemical characterization of the PePOs may be cleaved at two possible positions: G✄F and A✄F.

Determination of the substrate specificity of PgPepO and TfPepO. (A) Peptide and protein substrates were each incubated alone (control, ctrl) and with a PepO, with wild-type (wt) and catalytically inactive ExxxA mutants serving as negative controls, at substrate: enzyme mass ratios of 100:1 (big endothelin-1), 2,000:1 (insulin B-chain), 80:1 (casein), and 200:1 (α-casein). The products obtained were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry (MS). (B) Mixtures of angiotensinogen 1–14 and human big endothelin-1 (Big ET-1) incubated at 800:1 substrate: enzyme mass ratios with PepO wt, E527A (PepO), or E515A (TfPepO) mutants were separated by high-performance liquid chromatography. The substances corresponding to the peaks indicated by asterisks (*) were identified using MS (C, D) The identified mass spectrometry cleavage sites for both PepOs are marked on the primary structures of the substrates using differently colored triangles (C) and were used to create the cleavage logo with Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) (https://meme-suite.org) (D).

Crystal structures of PgPepO and TfPepO

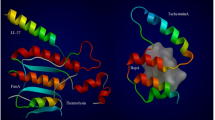

The crystal structures of PgPepO and TfPepO included variants with missing short fragments of 14 (PgPepO) and 10 (TfPepO) residues, located at the N-termini of the proteins. The secondary structures of PgPepO and TfPepO were mainly alpha-helical in nature and could be further separated into two large lobe-like subdomains connected by intertwining polypeptide segments, forming a smaller alpha-helical linker region. Together with the linker region, these two domains were found to form a central, spherical cavity, which contains the active site of each protease.

The catalytic site of each PepO was located within the cavity surface of the catalytic domain, was based around a zinc ion, and included the conserved active site motif HEXXH (Fig. 3A,E). The catalytic zinc cation of the PepOs was coordinated by side chains composed of two histidines and a glutamic acid residue (His526, His530, and Glu587 for PgPepO; His514, His518, and Glu575 for TfPepO), with the fourth coordination site being occupied by a water molecule. The proper positioning of the histidine residues was ensured by interactions with two aspartic acid residues (Asp533 and Asp591 for PgPepO; Asp521, Asp579 for TfPepO). The zinc ion coordination sphere was completed by a general acid–base glutamate (Glu527 and Glu515 in PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively), which polarizes the solvent and enhances its nucleophilicity (Fig. 3B, F). In addition, TfPepO contains a second, structural zinc, which is coordinated by Asp501, Asp502, Lys602, and Arg610. Its localization within the linker region suggested that TfPepO has a second, structural, zinc that stabilizes the linker region, which was 25% longer than that in PgPepO. The coordinated zinc ion and surrounding residues were found to create a small binding pocket with subsites S1, S1′, and S2′ (Fig. 3C,D). Subsites S1 and S2′ are shallow and S1′ is deep, and its hydrophobic base is formed by the leucine residues of the side chain at positions 651 (PgPepO) and 639 (TfPepO). The shape and properties of S1′ explain the preference of the enzymes for hydrophobic amino acids at the P1′ position of both studied PepOs (Fig. 2D).

Crystal structures of the PepOs. (A, E) General structures of PgPepO (A) and TfPepO (E), with a magnified view of the zinc-binding site with electron density map. N-terminal lobe, linker region and C-terminal lobe are colored green, cyan and purple, respectively. (B, F) 2D diagram of the interactions in the active sites of PgPepO (B) and TfPepO (F), generated by PDBsum. C, D) PgPepO (C) and TfPepO (D) active site binding pockets, with subsites: S1, S1’ and S2’ colored green, blue and yellow, respectively and residues. (G) Structure alignment of PgPepO (blue) and TfPepO (yellow). (H) Alignment of the structures of PgPepO (blue), TfPepO (yellow), and neprilysin (red; PDB accession no: 6SH1), along with the widths of the entrances into the catalytic sites. All the graphs and measurements were made using the PyMol program (version: 3.0.3).

To better visualize the differences between PgPepO and TfPepO, structural alignments of PepOs alone and with human neprilysin (PDB accession no.: 1DMT) were performed (Fig. 3G,H). The catalytic domains of all three M13 metalloproteases were characterized by low RMSD values (0.726–0.811), and relatively substantial differences were identified in the linker regions and regulatory domains, as well as in the arrangement of the regulatory domains relative to the active sites. The regulatory domain of TfPepO was further away from the catalytic domain, and therefore the space between these domains was larger than in PgPepO and neprilysin. These findings were confirmed by measuring the width of the entrance to the catalytic site cleft. For PgPepO and neprilysin, this was very similar (37.7 and 35.6 Å, respectively), but for TfPepO, it was over 9 Å larger, at 46.8 Å (Fig. 3H).

Human M13 proteases were found to contain disulfide bridges (six (hNEP) or five (human endothelin-converting enzyme 1, hECE1 and 2, and hECE2)) (Supplementary Fig. S1). On contrary to it, bacterial PepOs: PgPepO and TfPepO, and PepO from the bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus (PDB accession no.: 4IUW) did not contain disulfide bridges. The thermophilic properties of the PepOs (Fig. 1C) suggested that disulfide bridges are not essential for the stability of PgPeO and TfPepO.

PepOs are attached to the cell surface

At their N-termini, both PgPepO and TfPepO contain a putative signal peptide that is characteristic of secretory lipoproteins (Supplementary Fig. S1). To verify this prediction we used anti-PepO antibodies to identify proteins of interest in the fractions obtained from P. gingivalis and T. forsythia cultures. PgPepO and TfPepO were located in the cell envelope (CE) fraction, which contains both cell membranes and peptidoglycan, as well as in the outer membrane vesicles (OMV) (Fig. 4A). This observation indicates that PepOs are attached to the cell surface. To confirm this, we performed dot-blot analysis, in which inner membrane biotinylated proteins (a control for cell integrity)37 and PepO-deficient mutant strains (ΔpepO) were used as controls. The identical signals obtained for both whole cells and lysed cells confirmed that the PepOs are attached to the cell surfaces of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia (Fig. 4B). This finding was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. S7). In addition, the findings were further corroborated through mass spectrometry analysis, which showed the presence of PgPepO38 and TfPepO26 in OMV, and for T. forsythia alone, in the outer membrane39. Next, we checked whether whole cultures of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia or their purified proteinases hydrolyzed the substrate Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH, and found that whole cultures were highly efficient at processing the substrate, but that the previously described proteases produced by both bacterial species were not responsible for this activity (Supplementary, Fig. S8). We also measured the activities of fractions derived from the culture of wild-type and PepO-deleted variants of both bacterial species. The proteolytic activities of whole cultures were analyzed for the cells and the OMVs. The use of deletion mutants showed that PepO was responsible for all the measured activity in T. forsythia. However, in P. gingivalis, PepO deletion only reduced the activity by 42% in cells and 29% in OMVs (Fig. 4D), which suggests that, unlike T. forsythia, P. gingivalis secretes at least one protease additional to PepO that is capable of hydrolyzing the substrate.

PgPepO and TfPepO are attached to cell surfaces. (A) Western blots of culture fractions (whole culture (WC), cells (C), particle-free (without cells and OMVs) culture medium (pfM), soluble proteins derived from the cytoplasm and periplasm (CP/PP), cell envelope (CE), and outer membrane vesicles (OMV)) isolated from P. gingivalis and T. forsythia cultures. Blots were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-PepO antibodies. (B) Dot-blot analysis of P. gingivalis: W83 (wild-type, wt) and Pg ΔPepO (upper panels) and T. forsythia: wt (WT-Tf) and Tf ΔPepO (lower panels). Intact cells (upper row) and cells lysed by sonication (lower row) were used to detect PepOs (left panels) and biotinylated inner membrane proteins, (the biotin-containing 15-kDa biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB alias MmdC or PG1609) in P. gingivalis), (right panels). Dots on the PVDF membrane (dotted circle) were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-PepO antibodies and streptavidin-conjugated HRP (streptavidin-HRP). (C) Results of the flow cytometry analysis, showing the surface exposure of PepOs in P. gingivalis (upper histograms; W83 (wt) and ΔPepO) and T. forsythia (lower histograms; wt (WT-Tf) and ΔPepO) using appropriate anti-PepO antibodies. Brighter colors on the histograms represent negative controls (cells alone or cells stained with secondary antibodies). (D) Comparison of the activity against Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH in the obtained culture fractions (WC, C, cell-free (without cells, but with OMVs) culture medium, cfM) and OMVs derived from P. gingivalis (W83 and ΔPepO (upper graph)) and T. forsythia (wt (WT-Tf) and ΔPepO (lower graph)). Datasets were compared using one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001).

PepOs are the proteases responsible for Ang I cleavage

P. gingivalis and T. forsythia secrete numerous proteases. To exclude the possibility that proteases other than PepO hydrolyze Ang I, this peptide was incubated with cell-free media derived from the culture of both periodontopathogens, which contained both proteases secreted directly into the media (e.g., T. forsythia KLIKK proteases) and those bound to the cell surface and released in OMV (e.g., P. gingivalis gingipains). In both cases, Ang I was hydrolyzed to form Ang 1–9. Ang 1–7 could not be clearly identified, owing to its elution at the same time as peptides that were probably derived from the components of the media used. The lack of Ang I degradation by PepO-deficient mutants implies that PepOs were proteases responsible for Ang I hydrolysis by P. gingivalis and T. forsythia (Fig. 5A). Of note, after 1 h incubation ~ 30% of Ang I was cleaved. We chose to show longer incubation times to emphasize that PepOs are responsible for AngI degradation rather than other proteases secreted by P. gingivalis and T. forsythia.

T. forsythia in vivo PepOs are responsible for the cleavage of Ang I by T. forsythia and P. gingivalis and contribute to the virulence of T. forsythia in vivo. (A) Ang I was incubated with cell-free medium (M + OMV) derived from P. gingivalis (W83 and ΔPepO (upper row)) or T. forsythia (wild-type (WT-Tf) and ΔPepO (lower row)) and then separated on an HPLC column. The products of Ang I proteolysis were identified by comparison to the products of pure angiotensins separated under the same conditions. (B) Ang I was incubated with various enzymes (PgPepO, TfPepO, and their inactive mutants) and ACE in various configurations, and then separated by HPLC. The products of Ang I proteolysis were identified by comparison to the products of pure angiotensins separated under the same conditions. (C) Galleria mellonella larvae (N = 10 for each group) were infected with two different doses of T. forsythia (WT-Tf and TfΔPepO). The numbers of dead and live larvae were counted at the indicated time points, and the infection severity index was calculated based on the assessment of mobility and the melanization of larvae. Data are mean ± SD and are representative of three biologic replicates (C). Datasets were compared using Kaplan–Meier survival curves (C, upper panes) or one-way ANOVA (C, lower panes) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; na, not available, because only single larvae were alive).

ACE is the primary enzyme responsible for the formation of Ang II by the RAS in humans. By contrast, PgPepO and TfPepO activity caused the formation of Ang 1–9 and Ang 1–7. Therefore, we next determined the identity of the products formed from Ang I in the presence of an equimolar mixture of ACE and PepOs (Fig. 5B). As expected, ACE alone generated Ang II, but the addition of PgPepO or TfPepO resulted in the formation of no active peptide: neither Ang II nor Ang 1–7. This finding may be explained by the ability of ACE to hydrolyze Ang 1–740. However, the addition of captopril, an ACE inhibitor used to treat hypertension, to the mixture resulted in the formation of Ang 1–7, but not Ang II (Fig. 5B).

PepO contributes to the virulence of T. forsythia in a Galleria mellonella model

P. gingivalis is an asaccharolytic bacterium that use peptides rather than sugars as their energy source. Therefore, it may be that PgPepO, together with other proteases, is involved in the degradation of proteins to form short peptides, which can then be used metabolically by this microbe. To test this possibility, we evaluated the effects of PepO deletion on the growth of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia in a minimal medium consisting of DMEM containing 2% BSA. The lack of PepO had little effect on the growth of both species, indicating that PepOs do not participate in peptide acquisition by either pathogen (Supplementary Fig. S9).

The immune system of G. Mellonella includes complement-like proteins, opsonins, phagocytic cells (hemocytes), and antimicrobial peptides, and therefore has significant similarities to the human innate immune system41. This model was used to show that Streptococcus sanguinis PepO contributes to the virulence of this bacterium42. Specifically, G. mellonella larvae were infected with T. forsythia or P. gingivalis (a wild-type strain (WT or W83) or a mutant lacking PepO (ΔpepO) in one of two doses (108 or 109 CFU)), then the survival and the severity of infection, assessed based on melanization and larval activity, were monitored. In the case of P. gingivalis, no differences were observed between the WT strain and the deletion mutant (Supplementary Fig. S10). However, the lack of PepO in T. forsythia resulted in superior larval survival at the 109 dose and less severe signs of infection (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The RAS is principally responsible for the regulation of blood pressure, but is active in a number of tissues. A link between high blood pressure and periodontitis has previously been described, and the use of ACE inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension has been shown to worsen periodontal health43,44. In the present study, we have shown that homologous surface-attached proteases produced by two periodontopathogens, P. gingivalis (PgPepO) and T. forsythia (TfPepO), have opposing activities to ACE, because they process Ang I to form Ang 1–7, rather than Ang II.

TfPepO and PgPepO share substrate specificity, in the form of a preference for large hydrophobic amino acids on the carbonyl side of the scissile peptide bond, with other human and bacterial members of the M13 family, including neprilysin, ECE1, ECE2, Mycobacterium tuberculosis Zmp-1, S. pneumoniae PepO, and ACE2 (M2 family)30. Despite this and their high level of homology within the catalytic domain, TfPepO and PgPepO were found not to be inhibited by any of the tested inhibitors (Fig. 1F). An explanation for this has been provided by analysis of the crystal structure of neprilysin when complexed with the inhibitor LBQ657 (PDB accession no: 5JMY)45. This compound occupies the S1, S1′, and S2′ subsites within the substrate binding cleft. The methyl group of LBQ657 forms a hydrophobic bond with Phe544, forming the shallow S1 pocket, and P1′ biphenyl binds deep in the S1′ pocket. In addition, P2′ succinic acid interacts with Arg102 and Arg110. With respect to TfPepO and PgPepO, interactions are only possible with the S1′ pocket because there is a Tyr residue, instead of a Phe residue, in the S1 subsite, and only one of the two Arg residues that position the carboxylic acid terminus in the S2′ subsite is preserved in the PgPepO and TfPepO structures (Fig. 3C,D). These differences probably explain the lack of inhibition of the tested PepOs by LBQ657.

Crystal structures of PgPepO and TfPepO revealed two distinct protein states, suggesting the possibility of domain movement and breathing motion in macromolecules. The superposition of both crystal structures presented two different states – open and closed conformation of TfPepO and PgPepO, respectively. Closer investigation of solvent exposed, boarder parts of both domains show pairs of positively and negatively charged residues creating potential salt bridges in PgPepO structure (as an example of salt bridge pairs: Arg255-Asp534, Lys204-Glu638), as well as several other pairs creating hydrogen bond network, what might be stabilizing closed state of the protein. Similar potential salt bridge pairs and hydrogen bond network creating residues can be observed in corresponding regions of TfPepO (examples of potential salt bridge pairs: Lys339-Glu626, Arg244-Asp554). However, the protein was crystallized in an open conformation which might be the effect of crystal packing.

TfPepO hydrolyzed peptide bonds at a much greater distance from the termini of the substrates than PgPepO and other M13 metalloproteases (Fig. 2C). The explanation for this distinctive feature of TfPepO is likely the much wider entrance to the catalytic center, which allows larger substrates to access it. This is facilitated by the longer linker region in TfPepO (25% and 35% longer than in PgPepO and neprilysin, respectively), which is stabilized by an additional structural zinc ion, which is absent in other members of the M13 family of proteases, and provides greater separation between the catalytic and regulatory domains. Therefore, the width of the entrance to the catalytic cleft was also measured in other members of the M13 family of metalloproteases (Supplementary Fig. S11). In all of these, the width was similar to those of PgPepO and neprilysin, in the range 30.7–37.7 Å, and was significantly shorter than that of TfPepO (46.8 Å). This wider entrance to the catalytic cleft is probably a unique feature of TfPepO that distinguishes it from other members of the M13 family.

Upon removal of lipoprotein signal peptides during translocation across the inner membrane, the conserved cysteine residue becomes the novel N-terminus of the protein. Then this N-terminal Cys is modified by the attachment of a lipid molecule, providing membrane anchorage. However, it is impossible to predict whether this lipoprotein would remain in the inner membrane or be transported to the outer membrane based on the protein sequence alone. In the latter case, the lipoprotein may be located in the outer membrane inner or outer leaflets. Various methods used to determine the subcellular localization of proteins in bacteria indicate that TfPepO and PgPepO are attached to the cell surface, so they are present in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane. After the removal of the signal peptide during translocation through the inner membrane, PgPepO and TfPepO still have respective 19 and 17 amino acid residue-long unstructured fragments that precede the core of the molecule (Fig. 3A, E). These fragments probably ensure appropriate separation from the membrane, and thereby enable unrestricted activity of PepO on the bacterial surface. The T. forsythia cell is also surrounded by a proteinaceous crystalline S-layer, which can physically limit the access of substrates to TfPepO. However, the detection of TfPepO using IgG antibodies on flow cytometry indicates that the S-layer does not limit the activity of TfPepO in any way. This conclusion is corroborated by the fact that another T. forsythia surface lipoprotein, serpin miropin, inhibits even human plasmin (~ 80 kDa) through the formation of a covalent complex, despite the presence of the S-layer46.

The biologic function of PepO has been described in studies of other bacteria. PepO protects Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus pyogenes from the bactericidal activity of the complement system47, and it also increases the survival of the former in the Galleria mellonella model42. Streptococcus pneumoniae PepO binds to plasminogen and fibronectin and participates in immune evasion and host cell invasion36,48. In addition, the M. tuberculosis PepO, Zmp-1, improves the survival of the pathogen inside macrophages by blocking inflammasome activation49,50. The experiment performed using the G. mellonella model showed that TfPepO is probably involved in the evasion of host defense mechanisms (Fig. 5), whereas PgPepO is only responsible for host cell invasion51,52. The different functions of the studied PepOs can be explained by the fact that in P. gingivalis-derived gingipains, ~ 85% of the overall proteolytic activity is responsible for host response avoidance20, whereas this role is distributed among more proteases in T. forsythia, including KLIKK proteases and TfPepO22,23,24. Therefore, this strongly suggests that PgPepO and TfPepO do not play exactly the same roles in the physiology and/or virulence of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia, respectively.

The RAS system plays important roles, not only in the regulation of the circulatory system and kidney function, but also in periodontal tissues7, where all the critical elements of the system (angiotensinogen, renin, ACE, ACE-2, Ang I, Ang 1–9, Ang II, Ang 1–7, and AT1 and AT2 receptors)9, as well as the Mas receptor (Supplementary Fig. S12), are expressed. The formation of Ang II, in addition to increasing blood pressure, increases inflammation and oxidative stress2,3. Moreover, a reduction in Ang II signaling results in bone loss in mice53. PgPepO and TfPepO activity leads to the formation of Ang 1–7 from Ang I, and in the presence of ACE, they prevent the formation of Ang II; therefore, they probably reduce the concentrations of reactive oxygen species at the site of infection. This may be crucial for the survival of the obligate anaerobes P. gingivalis and T. forsythia and the protection of their virulence factors against oxidation54. These proposed anti-inflammatory effects of PgPepO and TfPepO are partially supported by the observation that the deletion of neprilysin, which is responsible for the metabolism of proinflammatory peptides, increases the sensitivity of mice to endotoxic shock55. After 1 h of incubation, ~ 30% of Ang I was cleaved, and we showed the result with a longer reaction time to emphasize that only PepO proteases are responsible for Ang I degradation by P. gingivalis and T. forsythia (Fig. 5A). This may raise questions about the physiological significance of the observed Ang I hydrolysis. On the other hand, the abolition of ACE action (Fig. 5B) and the results in the G. melonella (TfPepO only) model suggested that the observed Ang I hydrolysis by PepO is physiologically relevant. However, further experiments are needed to unequivocally verify this hypothesis.

Many clinical studies have shown that there is a higher risk of hypertension in people who have periodontitis. However, the successful treatment of periodontitis does not significantly reduce blood pressure56, and patients who take ACE inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension have worse periodontal health43,44,57. Given that in the presence of an ACE and its inhibitor, captopril, PgPepO and TfPepO not only prevent generation of Ang II by ACE, but produced Ang 1–7 from Ang I (Fig. 5B), it is tempting to postulate that the activity of bacterial PepO contributes to the deterioration of periodontal health in people taking ACE inhibitors. Although it would be premature to state that the activities of PgPepO and TfPepO contribute to the progression of periodontitis in such patients, the present data demonstrate that of the numerous proteases secreted by P. gingivalis and T. forsythia, PgPepO and TfPepO, respectively, are only proteases able to cleave AngI. Thus, the PepOs may impair the function of the RAS system by cleaving Ang I. However, this hypothesis need to be verified experimentally.

Methods

Reagents

Fast Digest BamHI and EcoRI, dNTPs, GeneJET™ Gel Extraction Kits, GeneJET™ PCR Purification Kits, GeneJET™ Plasmid Miniprep Kits, GeneRuler 1 kb DNA Ladder, GeneRuler 50 bp DNA Ladder, Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate, vials with glass inserts, Micro+™, Chromacol™, Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor™ 488, and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits were purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA). All the primers used in the study were synthesized by Genomed (Warsaw, Poland). T4 DNA ligase, Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase, Streptavidin-HRP, and Streptavidin-FITC were purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). The Genomic Mini System was from A&A Biotechnology (Gdańsk, Poland). The expression vector pGEX-6P-1, glutathione-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow, HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg and Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL columns, and LMW and HMW protein kits were obtained from GE HealthCare Life Sciences (Little Chalfont, UK). Aeris C18: analytical columns, Aeris 3.6 μm Peptide XB-C18 100 Å, LC Column 150 × 4.6 mm were from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA). Tryptic soy broth (TSB), hemin, N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM), menadione, E-64, leupeptin, captopril, lisinopril, OF, pefabloc, phosphoramidon, sacubitrilat (LBQ657), tiorphan, α-casein, angiotensin I, angiotensin II, angiotensin 1–7, angiotensinogen 1–14, human big endothelin-1, endothelin 1, fibrinogen, fibronectin, hemoglobin, casein, LL-37, insulin β-chain, Mca-(Ala7,Lys(Dnp)9)-bradykinin (Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp), peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule) and Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filters, 10 kDa MWCO, 15 mL were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Gibco (Waltham, MA, USA) and defibrinated sheep blood was from Graso Biotech (Starogard Gdański, Poland). Daglutril (SLV-306) was purchased from Axon Medchem (Groningen, Netherlands), FP-biotin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA), Human [D-Val22]-Big Endothelin-1 (16–38) was from Biomatik (Kitchener, ON, Canada), iodoacetamide (IAA) was from VWR, (Radnor, PA, USA), and angiotensin 1–7 was from APExBIO (Houston, TX, USA). Polyclonal rabbit primary antibodies against PgPepO and TfPepO were obtained from Proteogenix (Schiltigheim, France). Precision Plus Protein™ Dual Xtra Prestained Protein Standards, Precision Plus Protein™ Kaleidoscope™ Prestained Protein Standards, and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) and nitrocellulose membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail was from Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Syringe filters (0.22 and 0.45 μm) and 96-well transparent plates were purchased from Sarstedt (Nűmbrecht, Germany), Medical X-Ray Film Blue was from AGFA (Mortsel, Belgium), and 96-well black plates were from Nunc (Roskilde, Denmark). Galleria mellonella larvae were acquired from Egzotic Room (Plewiska, Poland). All other chemical reagents were obtained from BioShop Canada (Burlington, ON, Canada).

Bacterial culture and fractionation

T. forsythia ATCC 43037 WT and Tf ΔpepO, and P. gingivalis W83 (WT) and Pg ΔpepO were cultured (30 ml) in an anaerobic chamber (Whitley A85: Don Whitley Scientific, Bingley, UK) in an atmosphere of 90% nitrogen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 5% hydrogen at 37 °C. Liquid culture of both bacterial species was performed in enriched TSB (eTSB) broth containing TSB broth (30 g/l) and yeast extract (5 g/l), supplemented with hemin (5 mg/l), L-cysteine (0.5 g/l), along with menadione (2 mg/l) for P. gingivalis (PgeTSB), and 5% FBS and N-acetylmuramic acid (10 mg/l) for T. forsythia (TfeTSB). The solid medium for P. gingivalis and T. forsythia contained the appropriate eTSB medium, plus agar (1.5%) and defibrinated sheep blood (5%). Tf ΔpepO and Pg ΔpepO were also cultured in the presence of erythromycin (5 µg/ml). Bacterial cultures of T. forsythia (WT and Tf ΔpepO) with an optical density (OD600 nm) of 0.4–0.6 and P. gingivalis (W83 and Pg ΔpepO) with an OD600 nm of 1.2–1.5 were adjusted to an OD600 nm of 1.0 with PBS. These cultures (whole culture fraction, WC) were centrifuged (10 min, 4,500 × g, 4 °C), the supernatants (cell-free medium, cfM) were collected, and the cells (cell fraction, C) were suspended in PBS alone or supplemented (for immunoassays) with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Hoffmann-La Roche) and 200 µM TLCK (only for P. gingivalis). The supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm) and ultracentrifuged (1 h, 150,000 × g, 4 °C). The particle-free supernatants (particle-free medium fraction, pfM) were collected, and the pellets were washed with 25 ml of fractionation buffer (FB; 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0,02% (w/v) NaN3, (pH 7.5)). The ultracentrifugation was then repeated, and the pellets obtained (OMV fractions) were suspended in 250 µl of PBS (with the addition of appropriate inhibitors for use in immunoassays). The cells were disrupted using a UP50H ultrasonic homogenizer (Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH, Teltow, Germany; 10 cycles of 10 pulses of 0.5 s each, pulse amplitude 60%), then centrifuged (20 min, 10,000 × g, 4 °C) and the obtained supernatants were ultracentrifuged (1 h, 150,000 × g, 4 °C). The supernatants obtained (cytoplasm/periplasm fraction) were collected, and the pellets were washed with 25 ml of FB. The ultracentrifugation was then repeated, and the pellets were suspended in PBS (containing appropriate inhibitors if used for immunoassays) to yield the cell envelope fraction.

Cloning and mutant construction

The coding sequence of the full-length PgPepO gene (KEGG accession number: K07386) without the predicted signal peptide (SP) (23 C/A-689 W) was amplified by PCR directly from genomic DNA isolated from P. gingivalis W83 using the primers listed in Table S1. Next, the pGEX-6P-1 vector and the PCR product were digested with BamHI/EcoRI and the latter was ligated into the former. The sequence encoding TfPepO lacking the SP, (17 C/A-677 W), (GenBank accession number: KKY61269.1) was synthesized and cloned into pGEX-6P-1 using BamHI/XhoI by Genscript (Nanjing, China). The WT constructs (pGEX-6P-1-PgPepO, pGEX-6P-1-TfPepO) were used to obtain catalytically inactive mutants (PgPepOE527A and TfPepOE515A), in which alanine was substituted for the glutamic acid residue in the active site using a QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) and the primers listed in the Supplementary Table S1. The sequences of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Genomed, Warsaw, Poland).

Enzymatic activity assays

The activities of PepOs, unless otherwise mentioned, were determined in 100 µl of reaction buffer composed of Tris (100 mM), NaCl (150 mM), CaCl2 (2.5 mM), NaN3 (0.02%), and Pluronic F-127 (0.05%); pH 7.5, using Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH as the substrate. The enzymatic reactions were monitored in the wells of a 96-well black plate at 37 °C using increases in fluorescence (excitation/emission = 320/405 nm) using a SpectraMax Gemini EM reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) was calculated using Prism v9 (GraphPad, Boston, MA, USA) based on the reaction velocity (V) measured at various concentrations of substrate (1–50 µM). To determine the optimum pH, PepO activity was measured using the buffer Tris (100 mM), MES (50 mM), acetic acid (50 mM), NaN3 (0.02%) at pHs ranging from 5.0 to 11.0. To determine the optimum temperature, enzyme activity was measured after incubation at temperatures ranging from 4 °C to 99 °C for 30 min, after which the enzymatic reaction was stopped by the addition of OF (20 mM). To test the effects of temperature, inhibitors, reducing agents, and divalent metal cations on PepO activity, the proteases were incubated at temperatures of 4–99 °C in reaction buffer for 30 min, or with each additive in Tris (100 mM), NaN3 (0.02%); pH 7.5 for 15 min at 37 °C, and the enzymatic activity was determined as described above.

Determination of PepO cleavage specificity

The proteins human albumin, ferritin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, hemoglobin, bovine casein, and α-casein, and the peptides human big endothelin-1, human cathelicidin LL-37, and bovine insulin B-chain (4 µg) were incubated with PgPepO and TfPepO at enzyme/substrate mass ratios of 1:100 (big endothelin-1), 1:200 (α-casein, LL-37), 1:2,000 (insulin B-chain), 1:1,000 (LL-37), and 1:80 (other proteins) for 24 h (α-casein, big endothelin-1, insulin β-chain) or 7 days (other substrates) at 37 °C in Tris (100 mM), NaCl (150 mM), CaCl2 (2.5 mM), NaN3 (0.02%), Pluronic F-127 (0.05%), pH 7.5. The products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE58 (4%/12% and 4%/18% (T: C, 27.5:1) gels for the protein and peptide substrates, respectively) and mass spectrometry. Substrates incubated with PgPepOE527A and TfPepOE515A were used as negative controls.

Angiotensinogen 1–14 and human big endothelin-1 (30 µg) were mixed with PepOs to a final concentration of 10 nM and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to a final concentration of 0.1%. The products were centrifuged (10 min, 16,900 × g, 4 °C), and the supernatants were separated on an Aeris 3.6 μm Peptide XB-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm) using an acetonitrile gradient (2%–60%). Samples containing substrate alone and substrate plus an inactive PepO mutant were used as controls. The Mass Spectrometry Laboratory (Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland) identified the products of the proteolysis.

Deletion of PepO proteases in P. gingivalis and T. forsythia

DNA fragments containing an erythromycin resistance cassette (GenBank accession number: AF219231.1)59 and the PepO gene flanked by genomic upstream and downstream fragments were synthesized and cloned into pUC19 plasmid by Genscript (Nanjing, China). Deletion mutants were obtained by natural homogenous recombination. One microgram of suicide vector and 100 µl of electrocompetent cells were placed in a sterile, ice-cooled electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad), which was placed in a MicroPulser™ electroporator (Bio-Rad) and subjected to an electric pulse of 2.5 kV for 3 msec. Immediately after electroporation, 1 ml of the appropriate PgeTSB or TfeTSB medium prewarmed to 37 °C was added and the obtained mixtures were incubated overnight (~ 16–24 h) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. The mixture was then inoculated onto selective plates containing erythromycin (5 µg/ml). Genomic integration was confirmed by amplifying the genomic fragments containing the introduced mutations and sequencing them (Supplementary Table S1).

Western blot, dot blot, and flow cytometry analysis

For western blotting, proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred (1 h, 90 V, 10 mM CAPS, 10% (v/v) methanol (pH 11.0)) onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad) for 30 min, then probed with the appropriate polyclonal rabbit antibody against the PepO at a concentration of 1 µg/ml in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad), followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:20,000) (Merck), following washes in TTBS (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% (w/v) NaN3, 0.1% Tween-20 (pH 7.5)). The blots were developed using a Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) substrate kit and X-ray films or a ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad). For dot-blot analysis, isolated cells were divided into two portions, one of which was supplemented with SDS to a final concentration of 0.05% and disrupted by sonication (10 cycles, 10 pulses of 0.5 s each, pulse amplitude 60%) with a UP50H device (Hielscher Ultrasonics). Then, 2.5 µl of intact and sonicated cells were spotted onto PVDF membranes and analyzed as described above. For flow cytometry, cell suspensions were adjusted to an OD600 nm of 1.0, as described above, except that PBS–BSA buffer (PBS with the addition of 1.5% (w/v) BSA and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail) was used. One hundred microliter aliquots of cell suspension were transferred to 96-well conical plates, which were centrifuged (1,000 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). The pellets obtained were incubated for 30 min on ice with 100 µl of polyclonal rabbit anti-PepO antibody (30 µg/ml) in PBS–BSA, then with 100 µl of goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200 dilution) or Streptavidin − FITC at the same dilution. After 30 min of incubation on ice, the cells were washed three times with PBS–BSA and analyzed using a Guava® easyCyte™ flow cytometer (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) and InCyte™ Software (Merck). Cells not incubated with antibodies or with the secondary antibody alone were used as controls. Cell integrity in assays was controlled by detection of internal biotinylated protein in P. gingivalis (the biotin-containing 15-kDa biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB alias MmdC or PG1609) localized in inner membrane)37 and T. forsythia (many biotinylated proteins not exposed on the cell surface)60.

Analysis of Ang I hydrolysis by media used to culture P. gingivalis or T. forsythia

Bacterial cultures were centrifuged (10 min, 4,500 × g, 4 °C), and the supernatants (cell-free medium, M + OMV fraction) was collected. The reaction mixtures (final volume: 50 µl) contained 30 µg of Ang I and an amount of supernatant with activity against Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH equal to 10 nM of recombinant PepO. The samples were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C, then TCA was added to a final concentration of 3.5%, and the samples were incubated for 15 min on ice. TFA (final concentration: 0.1%) was added to the mixtures, and the samples were centrifuged (10 min, 16,900 × g, 4 °C). The supernatants were separated on Aeris 3.6 μm Peptide XB-C18 columns (150 × 4.6 mm) using an acetonitrile gradient (2%–80%). Samples containing only the substrate, the substrate and supernatant from PepO deletion mutants, and appropriate eTSB medium were used as controls.

Virulence of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia in a Galleria mellonella model

Only healthy larvae (Egzotic Room, Plewiska, Poland) without signs of melanization were used in the experiments. Groups of 10 larvae underwent the injection of 10 µl of a bacterial suspension containing 108 or 109 CFU of P. gingivalis (W83 and Pg ΔpepO) or T. forsythia (WT and Tf ΔpepO) cells into their caudal pairs of legs using a Hamilton syringe, or with 10 µl of PBS as a control. The larvae were then kept at 37 °C in 9-cm Petri dishes, without food, and their physical activity and melanization was monitored and scored for up to 72 h after the infection. The experiment was performed using three biologic replicates.

Crystallization of protein

Purified proteins in Tris (20 mM), NaCl (50 mM), pH 8.0 were concentrated to 10 mg/ml. Screening for crystallization conditions was performed using commercially available buffer sets in a sitting-drop vapor diffusion setup by mixing 0.2 µl of protein complex solution and 0.2 µl of buffer solution. Crystals of PgPepO were obtained at room temperature from solutions containing Tris pH 7.5, magnesium chloride (0.2 M), EDO (40% (v/v)), and PEG 8000 (15% (w/v)); pH 6.5, whereas crystals of TfPepO were obtained at room temperature from solutions containing sodium fluoride (0.3 M), sodium bromide (0.3 M), sodium iodide (0.3 M), 0.1 M buffer system comprising an imidazole/MES mix, ethylene glycol (40% (v/v)), and PEG 8000 (20% (w/v)); pH 6.5.

Determination and refinement of the protease structures

Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Crystallographic experiments were performed on a 14.1 beamline at the HZB Bessy, Berlin, Germany (PgPepO) and the 11.2 C beamline at the Elettra Synchrotron, Trieste, Italy (TfPepO). The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using XDS61, and subsequently merged using Aimless62. The PgPepO structure was solved using AutoSol, and anomalous data collected at the zinc wavelength and the resulting initial model were used for molecular replacement. The TfPepO structure was solved by molecular replacement using the MORDA pipeline and 3DWB PDB entry as a search model63,64. The models were automatically built using Buccaneer65, then manually rebuilt using Coot66, and further refined using REFMAC567 and phenix.refine. The data collection and refinement statistics for all the datasets are presented in the Supplementary Table S2. The final models were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 9FMA (PgPepO) and 9EYG (TfPepO).

Data availability

The coordinates of the herein determined experimental structures are available from the Protein Data Bank under accession number 9FMA (PgPepO) and 9EYG (TfPepO). The article was also published as preprint on bioRvix: (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.06.20.599981v1).

References

Triebel, H. & Castrop, H. The Renin angiotensin aldosterone system. Pflugers Arch. 476 (5), 705–713 (2024).

Weber, K. & Brilla, C. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac interstitium. Fibrosis and renin- angiotensin‐aldosterone system. Circulation 83, 1849–1865 (1991).

Welch, W. Angiotensin II-dependent superoxide: effects on hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 52, 51–56 (2008).

Howell, E. & Cameron, S. Neprilysin inhibition: A brief review of past Pharmacological strategies for heart failure treatment and future directions. Cardiol. J. 23, 591–598 (2016).

Thomas, M. et al. Genetic Ace2 deficiency accentuates vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in the ApoE knockout mouse. Circ. Res. 107, 888–897 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Upregulation of angiotensin (1–7)-Mediated signaling preserves endothelial function through reducing oxidative stress in diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 880–892 (2015).

Saravi, B. et al. The tissue renin-angiotensin system (tRAS) and the impact of its Inhibition on inflammation and bone loss in the periodontal tissue. Eur. Cell. Mater. 40, 203–226 (2020).

Santos, C. Functional local Renin-Angiotensin system in human and rat periodontal tissue. PloS One. 10, e0134601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134601 (2015).

Nakamura, T., Hasegawa-Nakamura, K., Sakoda, K., Matsuyama, T. & Noguchi, K. Involvement of angiotensin II type 1 receptors in interleukin-1β-induced interleukin-6 production in human gingival fibroblasts. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 119, 345–351 (2011).

Nazir, M. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 11, 72–80 (2017).

Isola, G. et al. Periodontal health and disease in the context of systemic diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 13, 9720947. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9720947 (2023).

Botelho, J. et al. Economic burden of periodontitis in the united States and europe: an updated Estimation. J. Periodontol. 93, 373–379 (2022).

Saini, R., Saini, S., Sharma, S. & Biofilm A dental microbial infection. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2, 71–75 (2011).

Grenier, D. & Mayrand, D. Functional characterization of extracellular vesicles produced by Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 55, 111–117 (1987).

Hajishengallis, G. & Lamont, R. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 27, 409–419 (2012).

Darveau, R., Hajishengallis, G. & Curtis, M. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J. Dent. Res. 91, 816–820 (2012).

van Winkelhoff, A., Loos, B., van der Reijden, W. & van der Velden, U. Porphyromonas gingivalis bacteroides Forsythus and other putative periodontal pathogens in subjects with and without periodontal destruction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 29, 1023–1028 (2002).

Holt, S. & Ebersole, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontology 38, 72–112 (2005).

Haffajee, A., Socransky, S., Patel, M. & Song, X. Microbial complexes in supragingival plaque. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23, 196–205 (2008).

Guo, Y., Nguyen, K. & Potempa, J. Dichotomy of gingipains action as virulence factors: from cleaving substrates with the precision of a surgeon’s knife to a meat chopper-like brutal degradation of proteins. Periodontol 2000. 54, 15–44 (2010).

Ksiazek, M. et al. KLIKK proteases of Tannerella forsythia: putative virulence factors with a unique domain structure. Front. Microbiol. 6, 312 (2015).

Karim, A. et al. A novel matrix metalloprotease-like enzyme (karilysin) of the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia ATCC 43037. Biol. Chem. 391, 105–117 (2010).

Koziel, J. et al. Proteolytic inactivation of LL-37 by karilysin, a novel virulence mechanism of Tannerella forsythia. J. Innate Immun. 2, 288–293 (2010).

Koneru, L. et al. Mirolysin, a lysarginase from Tannerella forsythia, proteolytically inactivates the human cathelicidin, LL-37. Biol. chem. 292, 10883–10898 (2017).

Ansai, T., Yu, W., Urnowey, S., Barik, S. & Takehara, T. Construction of a PepO gene-deficient mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis: potential role of endopeptidase O in the invasion of host cells. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 18, 398–400 (2003).

Friedrich, V. et al. Outer membrane vesicles of Tannerella forsythia: biogenesis, composition, and virulence. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 30, 451–473 (2015).

Park, Y., Yilmaz, O., Jung, I. & Lamont, R. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis genes specifically expressed in human gingival epithelial cells by using differential display reverse transcription-PCR. Infect. Immun. 72, 3752–3758 (2004).

Carson, J. et al. Characterization of PgPepO, a bacterial homologue of endothelin-converting enzyme-1. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 103, S90–S93 (2002).

Awano, S. et al. Sequencing, expression and biochemical characterization of the Porphyromonas gingivalis PepO gene encoding a protein homologous to human endothelin-converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 460, 139–144 (1999).

Rawlings, N. et al. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Re. 46, D624–D632 (2018).

Juncker, A. et al. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 12, 1652–1662 (2003).

Johnson, G. & Ahn, K. Development of an internally quenched fluorescent substrate selective for endothelin-converting enzyme-1. Anal. Biochem. 286, 112–118 (2000).

Sterpone, F. & Melchionna, S. Thermophilic proteins: insight and perspective from in Silico experiments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1665–1676 (2012).

Müller, J., von Roedern, E., Grams, F., Nagase, H. & Moroder, L. Non-peptidic cysteine derivatives as inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases. Biol. Chem. 378, 1475–1480 (1997).

Dudev, T. & Lim, C. Principles governing Mg, Ca, and Zn binding and selectivity in proteins. Chem. Rev. 103, 773–788 (2003).

Agarwal, V. et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae endopeptidase O (PepO) is a multifunctional plasminogen- and fibronectin-binding protein, facilitating evasion of innate immunity and invasion of host cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6849–6863 (2013).

Lasica, A. et al. Structural and functional probing of PorZ, an essential bacterial surface component of the type-IX secretion system of human oral-microbiomic Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 6, 37708. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37708 (2016).

Veith, P. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles exclusively contain outer membrane and periplasmic proteins and carry a cargo enriched with virulence factors. J. Proteome Res. 13, 2420–2432 (2014).

Veith, P. et al. Outer membrane proteome and antigens of Tannerella forsythia. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4279–4292 (2009).

Deddish, P. et al. N-domain-specific substrate and C-domain inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme: angiotensin-(1–7) and keto-ACE. Hypertension 31, 912–917 (1998).

Ménard, G., Rouillon, A., Cattoir, V. & Donnio, P. Galleria Mellonella as a suitable model of bacterial infection: Past, present and future. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 782733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.782733 (2021).

Alves, L. et al. PepO and CppA modulate Streptococcus sanguinis susceptibility to complement immunity and virulence. Virulence 14, 2239519. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2023.2239519 (2023).

Rodrigues, M. et al. Effect of antihypertensive therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on chronic periodontitis: a case-control study. Oral Dis. 22, 791–796 (2016).

Chatzopoulos, G., Jiang, Z., Marka, N. & Wolff, L. Relationship of medication intake and systemic conditions with periodontitis: A retrospective study. J. Pers. Med. 13, 1480 (2023).

Schiering, N. et al. Structure of Neprilysin in complex with the active metabolite of sacubitril. Sci. Rep. 6, 27909. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27909 (2016).

Sochaj-Gregorczyk, A. et al. Plasmin Inhibition by bacterial serpin: implications in gum disease. FASEB J. 34, 619–630 (2020).

Honda-Ogawa, M. et al. Streptococcus pyogenes endopeptidase O contributes to evasion from complement-mediated bacteriolysis via binding to human complement factor C1q. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 4244–4254 (2017).

Agarwal, V. et al. Binding of Streptococcus pneumoniae endopeptidase O (PepO) to complement component C1q modulates the complement attack and promotes host cell adherence. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15833–15844 (2014).

Master, S. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prevents inflammasome activation. Cell. Host Microbe. 17, 224–232 (2008).

Paolino, M. et al. Development of potent inhibitors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence factor Zmp1 and evaluation of their effect on mycobacterial survival inside macrophages. ChemMedChem 13, 422–430 (2018).

Miller, P. et al. Genes contributing to Porphyromonas gingivalis fitness in abscess and epithelial cell colonization environments. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 7, 378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00378 (2017).

Ansai, T. et al. Effects of periodontopathic bacteria on the expression of endothelin-1 in gingival epithelial cells in adult periodontitis. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 103, 327S–331S (2002).

Lima, M. et al. Receptor AT1 appears to be important for the maintenance of bone mass and AT2 receptor function in periodontal bone loss appears to be regulated by AT1 receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312849 (2021).

Fitzsimonds, Z. et al. Regulation of Olfactomedin 4 by Porphyromonas gingivalis in a community context. ISME J. 15, 2627–2642 (2021).

Lu, B. et al. Neutral endopeptidase modulation of septic shock. J. Exp. Med. 181, 2271–2275 (1995).

Muñoz Aguilera, E. et al. Periodontitis is associated with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 28–39 (2020).

Wang, I., Askar, H., Ghassib, I., Wang, C. & Wang, H. Association between periodontitis and systemic medication intake: A case-control study. J. Periodontol. 91, 1245–1255 (2020).

Schägger, H. & von Jagow, G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166, 368–379 (1987).

Fletcher, H. et al. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the PrtH gene. Infect. Immun. 63, 1521–1528 (1995).

Książek, M. et al. A unique network of attack, defence and competence on the outer membrane of the periodontitis pathogen Tannerella forsythia. Chem. Sci. 14, 869–888 (2022).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 125–132 (2010).

Evans, P. & Murshudov, G. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr. 69, 1204–1214 (2013).

Vagin, A. & Lebedev, A. MoRDa, an automatic molecular replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Eng. 71(a1), S19 https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053273315099672 (2015).

Schulz, H., Dale, G., Karimi-Nejad, Y. & Oefner, C. Structure of human endothelin-converting enzyme I complexed with phosphoramidon. J. Mol. Biol. 385, 178–187 (2009).

Cowtan, K. The buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1002–1011 (2006).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 (1997).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 75, 861–877 (2019).

Acknowledgements

X-ray data were obtained at the BESSY II 14.1 beamline at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie (Berlin, Germany) and the 11.2 C beamline at the Elettra Synchrotron (Trieste, Italy). In addition, we thank the MCB Structural Biology Core Facility (supported by a TEAM TECH Core Facility/2017-4/6 grant from the Foundation for Polish Science) for providing instruments and support.

Funding

This study was funded by the Narodowe Centrum Nauki (NCN, National Science Centre, Kraków, Poland) grant nos. UMO-2018/31/N/NZ1/02891 (to I.W.) and 2019/35/B/NZ1/03118 (to M.K). The open-access publication has been supported by the Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: M.K. designed research; I.W., K.Ż., N.M., J.B., V.M., E.B., T.K., J.K., I.B.T., and P.G. performed research; I.W., K.Ż., J.J.E., P.G., J.P. and M.K. analyzed data; and I.W., K.Z. and M.K. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waligórska, I., Żak, K.M., Mikrut, N. et al. Periodontopathogens degrade angiotensin I from the human renin–angiotensin system through surface-attached proteases. Sci Rep 15, 43309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27891-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27891-0