Abstract

While neural responses in striatal, limbic and somatosensory regions are known to track individual differences in loss aversion, a system-level view of its neural basis is still lacking, and, in particular, a possible association with white matter (WM) microstructural organization remains unexplored. We investigated the relationship between behavioural loss aversion and fractional anisotropy (FA), a popular diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metric of WM coherence, in 130 healthy young participants. Loss aversion was positively correlated with FA in bundles that might underpin attentional biases towards negative stimuli (forceps minor), the associated aversive affective states (fornix), and the motivational incentive to avoid them (cingulum). Conversely, a negative correlation was found in bundles previously associated with reward sensitivity through projections to fronto-striatal structures (superior longitudinal fasciculus and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus), possibly decreasing loss aversion by enhancing the salience of potential gains. The observation of positive and negative correlations with FA in distinct WM bundles supports the view that loss aversion reflects the interplay between oppositely-directed reward- and loss-oriented patterns of brain activity and connectivity. These results strengthen the view that loss aversion represents a stable neuro-cognitive component of one’s behavioural attitude in risky decision-making, rather than a transient fearful reaction to choice-related information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Against economic prescriptions based on so-called “expected value”1, which weigh the positive and negative consequences of choices equally, individuals are typically more inclined to avoid losses than acquire gains2. This behavioural asymmetry is considered to reflect a cognitive mechanism of “loss aversion” (LA), i.e., weighing prospective losses more than equivalent gains in decision-making under risk2. Individual differences in LA are usually investigated with series of mixed gambles offering equal (50%) probability of either gaining or losing different amounts of money3,4,5, and measured in terms of a λ coefficient representing the multiplicative weight assigned to losses compared with gains4,6. This well-established approach highlighted an average λ around 2 in healthy participants6,7,8, with a minority of loss-neutral (λ ≈ 1) individuals6,9.

Likely due to its relationship with critical drivers of behavioural control such as interoception (i.e., “feeling one’s own body”10), and emotion regulation11, LA is considered to shape not only economic decisions (e.g., financial market12) but virtually any kind of evaluation (e.g., organ donation13, brand choice14, food choice15). Unveiling the neuro-cognitive precursors of individual differences in LA might therefore enable a better understanding of human nature4, which explains why many efforts have been made to investigate its neurobiological correlates.

Crucial evidence, in this respect, has been provided by neuroimaging studies addressing the relationship between LA and metrics of brain function and/or structure, and interpreted with the lens of Neuroeconomics16. In this framework, decision-making is considered to reflect the interplay between appetitive drives generated by frontomedial-striatal structures and aversive drives involving limbic and somatosensory structures, favoring approach and avoidance behaviour, respectively17. These appetitive and aversive neural systems are generally activated by prospective gains and losses, respectively18. Neuroimaging studies have shown, however, that some of their components underpin oppositely-directed patterns of “neural loss aversion” (NLA), i.e., a bidirectional response in which the asymmetry between loss- and gain-related components reflects individual differences in behavioural LA (9,19 for an overview see4). Such pattern has been found in the posterior insula and amygdala (more activated by anticipated losses than deactivated by gains (9,16; i.e., “loss-oriented NLA”), as well as in the ventral striatum and midcingulate cortex (more deactivated by anticipated losses than activated by gains (9,19,20; i.e., “gain-oriented NLA”). In the midcingulate cortex, the presence of both gain- and loss-related neural signals might then support cost-benefit analyses4,21, as well as behavioural adjustments in conjunction with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC22).

This view of the neural basis of LA is supported by distinct studies, showing a relationship between its behavioural expression and the responsiveness of both amygdala11,20,23 and insula24,25, as well as grey matter (GM) volume in amygdala, striatum, insula and thalamus9,26. The involvement of the amygdala is also supported by lesional evidence27. Other results however suggest that these brain structures might play a more complex role in LA, thus raising the need for further inquiry4. First, against some of the aforementioned findings, a negative correlation has been reported between LA and GM volume in the posterior insula28, and suggested to reflect anomalous salience detection and loss processing, in turn biasing choices towards loss avoidance. Moreover, the activity of the amygdala was found to track the deviation of the gain-loss ratio from the individual decision boundary (λ), which suggests that it might encode a “subjective value” integrating appetitive and aversive signals rather than these single components alone29. Finally, against its involvement in coding prospective and actual gains30, the striatum was found deactivated by the presence of possible high performance-dependent gains, that might be coded as negative stimuli because they emphasize the adverse consequences of failure31. Overall, these findings might appear to cast doubts on the view of LA as emerging from the interplay between gain- and loss-oriented patterns of neural loss aversion involving frontomedial-striatal and limbic-somatosensory structures, respectively.

We tackled this issue by investigating - for the first time - the possible association between LA and fractional anisotropy (FA), a popular metric of white matter (WM) organization estimated through diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). To date, DTI has been only used to investigate a relationship between FA and individual differences in other facets of decision-making, such as impulsivity32,33,34, temporal discounting35,36, reward-based learning37, and risk-seeking on the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART)38,39. In particular, the integrity of connections between midbrain and striatum was positively correlated with total earnings on the BART39, while those between insula and striatum were additionally associated with the overall number of risky choices. These data suggest that adaptive decision-making requires a balance between neural signals tracking (a) the size of a potential reward, and (b) value integration and risk representation, conveyed by tracts connecting the striatum with, respectively, midbrain and insula39. The lack of previous DTI studies on LA is surprising not only because this level of evidence might provide novel insights into a controversial literature, but also because of the well-established relationship between such metrics and task performance40,41, contributing to unveil the neural bases of cognitive processes both in healthy42,43 and clinical44,45 populations.

On these grounds, we investigated a relationship between behavioural LA and WM-FA in a large sample of 130 healthy young participants. Exploratory analyses were also performed, by modeling additional DTI metrics such as axial diffusivity (AD), mean diffusivity (MD), and radial diffusivity (RD). Based on the available related evidence39,46, we first predicted that this association would involve bundles connecting insula, striatum, and the prefrontal cortex (PFC). In particular, based on the hypothesis that LA reflects the interplay between gain- and loss-oriented patterns of neural loss aversion9, we predicted that it would correlate positively and negatively with FA in WM bundles involving limbic-somatosensory and frontomedial-striatal structures, respectively.

Materials and methods

Participants

We collected behavioural and DTI data from 130 right-handed healthy volunteers (70 females and 60 males; mean age = 24.43 years, standard deviation (SD) = 3.32, range = 18–40). None of the participants had a history of substance abuse or neuropsychiatric diseases, nor reported to be on a medication that might interfere with cognitive functions. They gave their written informed consent to the experimental procedure, that was approved by the local Ethics Committee and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Behavioural data collection

Participants’ choices in a series of mixed-gambles allowed to estimate their degree of LA, under the assumption that the latter must be isolated from risk attitude (i.e., sensitivity to outcome variance) because both are involved in anticipatory evaluation processes10. To this purpose, before the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) session, they participated in two behavioural tasks, that were presented in counterbalanced order with random shuffling of trial order. In one task they were presented with a series of 49 mixed (i.e., “gain-loss”) gambles requiring choosing between the status quo (i.e., 0) and a gamble that might result in equally probable (50% probability) gain or loss. The gain-loss values, sampled from a 7 × 7 matrix, were centered to a λ level of 2, which is representative of the general population2,7,8. The second task included 30 “gain-only” gambles requiring choosing between a certain (100% probability) gain outcome and 50% chances of a larger gain (or 0).

Prior to participation, they received detailed instructions and completed a training session to familiarize with task requirements. Moreover, they were provided with a monetary incentive, and asked to place it in their wallet3,11,47. They were then informed that this sum would increase or decrease according to their actual performance in the tasks, with their final payoff depending on the outcome of one gain-loss trial and one gain-only trial randomly drawn from those played.

MRI data acquisition

We collected Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) MRI data with a General Electrics (GE) Discovery MR750 3-Tesla scanner (GE Healthcare), equipped with a 16-channels head coil. Participants were positioned on the scanner bed, and both foam pads and earplugs were used to make the acquisition more comfortable, and to minimize head movements. A DTI diffusion scheme was used, and 81 diffusion sampling directions were acquired with b-value = 1000 s/mm2, in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm2, and slice thickness = 2 mm, plus 2 non-DWI (b0) images.

LA Estimation

The individual LA level was estimated from each participant’s choices, under the assumption that both gain-loss and gain-only trials are necessary to separate loss aversion from risk aversion10. In keeping with models derived from Prospect Theory2, the probability of accepting a gamble can be estimated as follows:

where G is the gain (G > 0), L is the loss (L < 0 for gain-loss trials and L = 0 for gain-only trials), B is the guaranteed gain (B = 0 for gain-loss trials and B > 0 for gain-only trials), \(\:{p}_{G}\)=0.5 is the probability of a gain and \(\:{p}_{L}\)=1-\(\:{p}_{G}\)=0.5 is the probability of a loss. The free parameters of the model are: (a) the LA lambda (λ), i.e., the multiplicative weight associated with anticipated losses compared with gains; (b) the risk attitude rho (ρ), i.e., the curvature of the value function \(\:u\left(x\right)={x}^{\rho\:}\) that embodies the diminishing sensitivity to increasing outcome; and (c) the choice consistency or “softmax temperature” (µ), i.e., a measure of noisiness vs. systematicity in choices. These parameters were individually computed via maximum likelihood estimation with MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Pre-processing and connectometry analysis of MRI-DTI data

We used DSI Studio (“Chen” release; http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org) both for the pre-processing and the connectometry analysis of MRI-DWI data. The “FSL eddy” tool was used to correct for eddy current distortions, through the integrated interface in DSI Studio. Imaging data underwent both visual and automatic quality control steps, with raw diffusion data being checked for major movements, or “bad slices” with artifacts, both before and after the FSL eddy correction. Neighboring DWI correlation was used as an indicator of the final quality of diffusion data, with minimum and average values of 0.79 and 0.85, respectively. The accuracy of b-table orientation was examined and adjusted by comparing fiber orientations with those reported in a population-averaged template48.

MRI connectometry is grounded in the concept of local connectome, i.e., “the degree of connectivity between adjacent voxels within a white matter fascicle, quantified by the density of diffusing spins”49. The individual diffusion MRI datasets were reconstructed in the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using q-space diffeomorphic reconstruction50, with a diffusion sampling length ratio of 1.25, through restricted diffusion imaging51. DSI Studio employs different algorithms for the computation of tensor-derived metrics, depending on the acquisition protocol. Since single-shell images with a b-value of 1000 s/mm² were collected, we applied the diffusion tensor model recommended for datasets with b-values below 1750 s/mm2, and data were resampled to 2 mm isotropic. For each voxel, diffusion tensors are computed and sampled along predefined WM fiber directions derived from a standard atlas. This sampling procedure results in quantitative measures of local connectome integrity, reflecting the degree of connectivity between adjacent voxels along specific fiber pathways. For each subject, the resulting local connectome measures are arranged into a one-dimensional vector. These individual vectors are then concatenated across all participants to form a two-dimensional matrix of size m × n, with m representing the number of local connectome features per subject, and n the total number of participants, respectively. This matrix is subsequently modeled in statistical analyses to assess the relationship between local connectome features and the behavioral variable(s) of interest.

Here we used Diffusion MRI connectometry52 to generate the correlational tractography based on the requirement of a non-parametric Spearman correlation between individual voxel-wise FA and λ (i.e., LA) values. To this purpose, we used a deterministic fiber tracking algorithm53 with a seeding region placed at the whole brain, while the cerebellum was excluded from tracking. To isolate the bundles in which FA values were significantly correlated with behavioural LA we used a p< 0.05 threshold, corrected for multiple comparisons with False-Discovery-Rate (FDR54), and a minimum of 10 tracts. The FDR was estimated with a nonparametric, permutation-based, testing procedure. Namely, the connectome matrix underwent 4000 random permutations generating an equal number of “null” local connectome matrices. For each permuted matrix, an automated fiber tracking algorithm was used to reconstruct pathways showing considerable associations with LA (T > 2.5). The lengths of the resulting tracts on each permutation were recorded to generate a null distribution of tract lengths. This was then compared to the distribution obtained from the actual (non-permuted) data, thereby allowing to assess whether the observed tract-level associations exceeded what would be expected by chance. The tracts that were positively or negatively correlated with behavioural LA at p < 0.05 FDR corrected were then clustered through the DSI “Recognize and cluster” function. The same connectometry pipeline was also used in a control analysis modeling sex as covariate, to assess its possible effect on FA results.

Importantly, although advanced diffusion models such as “Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging” (NODDI55) or “Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging” (DKI56) can provide additional microstructural insights, we used DTI for its robustness, widespread validation, and compatibility with our dataset in terms of b-value and number of directions. Moreover, FA has been previously related to behavioral decision-making attitudes (e.g.,57) - thus enabling a comparison with available evidence - and provides a reliable proxy of WM integrity. Since the latter can be assessed via further DTI metrics of WM microstructure, we performed exploratory analyses of mean diffusivity (MD, tracking global tissue density) as well as axial and radial diffusivity (AD and RD, tracking tissue coherence and myelination), respectively.

Results

Behavioral results

LA data were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov d = 0.192, Shapiro-Wilk: W = 0.71143, p < 0.0001). In keeping with a well-established literature8, the mean and median of behavioural LA were 2.109 and 1.946 (interquartile range (IQR) = 0.609), respectively, with no significant difference between males and females (Mann-Whitney U = 1943, p = 0.466). The mean LA degree of our sample was significantly higher than the “loss-indifference” λ = 1 (p < 0.0001) but not significantly different from λ = 2 (p = 0.334), which confirms the tendency to weigh potential losses about twice as much as potential gains in decision-making under risk.

DTI results

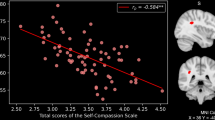

Figure 1 depicts the WM bundles showing a significant relationship between whole-brain FA values and behavioural LA in connectometry analyses. We found a positive correlation between LA and FA in the fornix, cingulum and forceps minor (i.e., the anterior part of corpus callosum) bilaterally (Fig. 1-top). Conversely, a negative correlation with LA was observed in the bilateral dorsal part of the superior longitudinal fasciculus and left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF and ILF), as well as in the bilateral inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), bilateral parahippocampal cingulum, right frontal aslant tract (FAT) and right forceps major (i.e., the posterior part of corpus callosum) (Fig. 1-bottom). Correlation values ranged from 0.22 to 0.26 (Table 1), indicating a small effect-size. In keeping with the lack of a significant effect of sex on LA, these results were confirmed when including this variable as covariate (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Exploratory analyses on other DTI metrics unveiled a positive correlation between behavioural LA and AD in the right cingulum, while a negative correlation was detected in the bundles spreading bilaterally towards the forceps major and the tapetum of the corpus callosum (Supplementary Fig. 2A-B). The latter negative relationship was also found with MD and RD, that instead displayed no significant positive correlation with LA (Supplementary Fig. 2C-D).

The top figure sector depicts 3D tractograms of WM bundles showing a positive correlation between behavioural LA and FA in connectometry analyses, i.e., fornix (red), cingulum (green), and forceps minor (blue). The bottom figure sector shows the bundles in which FA is negatively correlated with behavioural LA, i.e., superior longitudinal fasciculus (red), left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (green), parahippocampal cingulum (blue), inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (magenta), alongside right forceps major (yellow) and right frontal aslant tract (black). Scatterplots depict the relationship between FA and LA for selected representative tracts represented by the same color. Statistics were thresholded at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons with False Discovery Rate, with minimum number of 10 tracts. Following10,11, LA was recalculated as its natural logarithm prior to display.

Discussion

The neural correlates of LA have been extensively investigated both in terms of brain response with fMRI4,6, and of underlying GM properties with voxel-based-morphometry (VBM26). Instead, a possible relationship with structural connectivity, and particularly WM microstructural organization, remains unexplored. We aimed both to fill this gap, and to inform a partially inconsistent literature on the roots of LA in the neural mechanisms shaping approach and avoidance behaviours. To this purpose, we investigated a possible relationship between behavioural LA and fractional anisotropy (FA), a popular DTI metric of WM organization, in a large sample of 130 healthy young participants. In particular, we aimed to provide novel insights into the hypothesis that individual differences in LA reflect the interplay between oppositely-directed mechanisms of neural loss aversion involving fronto-striatal vs. limbic-somatosensory structures4,9. In line with this view, we found both positive and negative correlations between behavioural LA and FA in bundles connecting distinct brain networks.

As expected, we observed a positive correlation between LA and FA in WM bundles connecting key nodes of limbic-somatosensory networks, such as the fornix, cingulum and forceps minor. The available evidence on the connectivity patterns of these bundles, and the resulting cues about some of their possible functional roles, help refine the picture of LA as emerging from the interplay between brain networks promoting punishment vs. reward sensitivity. The fornix connects the hippocampus to different subcortical nodes of the limbic system, such as the septal nuclei, mammillary bodies, and hypothalamus58. It is considered to convey interoceptive signals, thereby supporting different facets of emotional and motivational learning such as fear conditioning, reversal learning, as well as episodic and non-declarative memory59. While animal studies show that fornix lesions impair freezing in fear conditioning (particularly involving the encoding and retrieval of contextual memory60), evidence from human participants suggests that this projection tract plays a key role in fear and anxiety61, which might explain why its alterations reflect in affective dysregulation62. Also the cingulum is a key component of the limbic-emotional system63, originating in the medial temporal lobe (amygdala and parahippocampal gyrus64) and encircling the corpus callosum up to the subgenual cortex65,66,67. On their way, cingulum fibers receive projections from regional “U-shaped” association fibers interconnecting the temporal, occipital, parietal, and frontal lobes, likely interfacing their neural signals and thereby supporting complex functions at the crossroad of affective, executive and motivational domains68,69. While this complex neural circuitry accounts for the multifaceted functional role of the cingulum68, LA was specifically related to FA of its anterior sector, previously associated with decision-making and its modulation by affective cues63. Observing this relationship also for AD suggests that behavioral LA is also modulated by tissue coherence, alongside microstructural integrity tracked by FA, in the cingulum. Finally, the forceps minor, also known as the anterior forceps, connects the medial and lateral PFC bilaterally70, crossing the midline via the genu of the corpus callosum71,72, and is considered to underpin emotion regulation and attention control skills73. Interestingly, the FA of the forceps minor has been found correlated with the severity of symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)74, which might reflect its role in biasing information processing towards negatively-valenced affects, cognitions and/or motivations75. This hypothesis is also supported by studies on rats injected with quinpirole, an agonist of dopamine D2/D3 receptors eliciting OCD-like symptoms76. Compared with control rats, indeed, these animals displayed compulsive/checking behavior, associated with larger FA values in the forceps minor (77 but see78 for different results, and79 for an overview). The involvement of these WM bundles in LA should be interpreted in the light of the direct relationship between higher FA values and more efficient neural signaling (i.e., faster and more reliable information transfer along axons80), as confirmed by the well-established FA decrease in a variety of pathological conditions such as Alzheimer disease81, Parkinson’s disease82, or frontotemporal dementia83. Under this assumption, the positive correlation with FA in the forceps minor, fornix and cingulum might reflect the contribution of these bundles to the different cognitive-attentional, affective and motivational facets of LA, enhancing, respectively, the attentional salience of losses over gains, the associated negative affective states, and, accordingly, the motivational incentive for loss/risk avoidance. By supporting the attentional and affective processing of valenced stimuli84 through fronto-limbic connnections, these bundles might drive the overweighing of negative ones that is inherent in the notion of LA. The bilateral engagement of evolutionarily ancient structures, such as the limbic regions, in supporting LA may reflect a deeply rooted neural mechanism for avoiding harm and negative outcomes, potentially accounting for the widespread and cross-species persistence of this bias across cultures and developmental stages6.

The fact that FA in other WM tracts was negatively correlated with behavioural LA fits with the existence of an oppositely-directed neural circuitry, promoting reward seeking even more than loss avoidance. Such a relationship was found in the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) bilaterally, alongside the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) - all conveying signals from caudal to rostral prefrontal areas - as well as in the parahippocampal cingulum bilaterally alongside right forceps major and frontal aslant tract. Concerning the SLF, among its three branches connecting frontal and parietal areas85, we found a positive correlation with LA in its dorsal component (i.e., SLF I), which connects the superior parietal and superior frontal cortex (particularly projecting to dorsal premotor and dorsolateral prefrontal regions)86. While SLF I is generally considered to support the voluntary orientation of visuospatial attention and motor control85, in the case of decision-making a positive correlation was previously found between FA in the SLF and reward sensitivity87. This finding fits both with the notion that the efficiency of this circuitry is inversely related to punishment sensitivity and its behavioral outcomes such as loss/risk avoidance, and with evidence of decreased FA, in the SLF, in a clinical condition characterized by decreased reward seeking88 such as depression89. Also in the case of the IFOF, a negative correlation between FA and LA might be interpreted in terms of its role in enhancing the salience of rewards90. This ventral tract connects the inferior and medial occipital cortex (lingual gyrus and cuneus) to the medial and lateral sectors of the orbitofrontal cortex91, that are known to represent multiple facets of reward value by integrating positively- and negatively-valenced signals92,93. Some fibers of this tract project also to the striatum, thus establishing a cortico-striatal connection94 that is known to support reward sensitivity95,96. The close relationship between the structural properties of this bundle and the functional responsiveness of its target structures has been previously confirmed by a positive correlation between FA in the IFOF and reward-related activation in the ventral striatum90,97. Alongside these data, our evidence of a negative correlation between LA and FA in the IFOF suggests that - similarly to the SLF - this bundle conveys neural signals enhancing the salience of expected rewards even more than possible losses.

Importantly, observing opposite correlation patterns between LA and FA in different WM tracts not only fits with the presence of both gain- and loss-oriented “neural loss aversion” drives9,19, but additionally highlights the need of further mechanisms in charge of conflict monitoring and resolution. This requirement might explain the involvement of the right frontal aslant - connecting the caudal portion of the superior frontal gyrus (SFG) with the ventral premotor cortex and the caudal inferior frontal gyrus98 - that has been previously associated with inhibitory control and conflict monitoring for action99. In line with the lateralization of our findings, this bundle is considered to convey neural information supporting conflict resolution and choice selection, particularly in the right hemisphere100, as well as predictive over reactive strategies101. Conflict resolution might be also supported by the forceps major102, connecting the occipital lobes through the splenium of the corpus callosum103, in which a negative relationship with behavioural LA was also found for AD, MD and RD, in addition to FA. This bundle is primarily considered to mediate a general-purpose function such as the integration of visual information104, which helps interpreting its role in key processes for conflict resolution such as executive functioning and working-memory105. Interestingly, FA of both the SLF and the forceps major have been associated with high impulsivity in healthy participants performing a Delay Discounting task, thus supporting the view that both bundles are involved in reward seeking32.

There are limitations to this study. First, although using corrected statistical thresholds is expected to ensure robust findings, the observed associations between DTI metrics and LA were generally weak, and could be detected only through a tract-wise correction approach. This is not surprising, however, as other explanatory levels such as functional connectivity might be expected to shape LA even more than WM features, which highlights the importance of addressing this relationship with a multimodal approach merging distinct (f)MRI features. The strength of findings might also reflect some methodological limitations. On one hand, while DTI provides meaningful indices of WM microstructure such as FA, future studies may further unveil the neurobiological bases of LA via more advanced models such as NODDI or DKI54,55. Moreover, the lack of an explicit correction of susceptibility artifacts during preprocessing may have affected the spatial accuracy of our findings, particularly in frontal and anterior temporal WM bundles. However, several prior studies have reported significant associations between DWI-DTI metrics and cognitive-behavioral measures even without such correction, and our relatively large sample is expected to enhance the robustness of the observed effects. Finally, interpreting some of the observed negative correlations is not straightforward, in the light of the available literature. On one hand, the interpretation of the IFOF role in LA remains controversial, as the opposite evidence of a negative correlation between reward sensitivity and WM integrity in this tract has been also reported87. One possible account of such inconsistency is that the latter study focused on fun-seeking, thus measuring sensitivity to signals of reward or non-punishment while neglecting the evaluation of truly negative events such as losses, and, therefore, of LA. Another unexpected finding is the negative correlation between LA and FA value in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), a ventral tract connecting the occipital cortex to key nodes of the anterior and medial temporal lobe106 such as amygdala and hippocampus107. This fasciculus has been associated with social and spatial perception, and with semantic processing108. Cues into its possible role in LA come from clinical studies, reporting reduced FA of this bundle in individuals with social anxiety disorder109, which might reflect the bias towards negative information characterizing this condition110. Moreover, alterations of the ILF have been associated with impulsivity in adolescents with a family history of dependence111. In the light of these previous findings, the present evidence suggests that the ILF might contribute to the modulation of decision-making by affectively-valenced signals, and therefore to individual differences in the sensitivity to prospective losses vs. gains. Moreover, in line with evidence of stronger left-lateralized ILF connectivity supporting semantic, spatial, and emotional processing108, our findings indicate that only the left tract was implicated in LA. Finally, while behavioural LA was positively correlated with FA in the anterior part of the cingulum, the opposite pattern was found in its posterior part, i.e., the parahippocampal cingulum. The available evidence from patients with memory deficits suggest that this bundle might play a role in memory functions112, but whether this holds in normal conditions remains debated62. Therefore, although memory processes might support decision-making113,114,115,116,117, further evidence is required to clarify the role played by this bundle in LA.

In conclusion, we report the first evidence linking WM microstructure to individual differences in LA in healthy young adults, providing novel insights across multiple levels of analysis. Observing both positive and negative correlations between LA and FA in distinct WM bundles support the presence of two oppositely-directed – i.e., loss-oriented and gain-oriented - neurocognitive patterns underlying LA. The former appears to enhance LA via greater WM microstructural coherence in bundles that might underpin attentional biases towards negative stimuli (forceps minor), the associated aversive affective states (fornix), and the motivational incentive to avoid them (cingulum). In contrast, the gain-oriented pattern, which may attenuate LA, involves bundles previously associated with reward sensitivity through projections to fronto-striatal structures (superior longitudinal fasciculus and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus), possibly decreasing loss aversion by enhancing the salience of potential gains.

These findings were largely supported by the analysis on AD, albeit involving less extensive networks, which fits with the association between the degree of axonal coherence captures by this parameter118 and WM organization as coded by FA in healthy individuals119. Instead, the general lack of significant findings for MD and RD warrants further investigation, through targeted studies, to clarify whether these indices can meaningfully reflect the relationship between cognitive processes and structural connectivity in healthy individuals, or whether they are more suitable as clinical markers of myelination (RD) and global tissue density (MD)120.

These findings contribute to a longstanding debate on the nature of LA. On one hand, observing that individual differences in its behavioural expression also reflect the responsiveness of brain structures involved in affective and interoceptive processing (see121 for a recent meta-analysis) might be considered to suggest that this “cautionary brake on behaviour”27 constitutes a transient fearful overreaction elicited by choice-related information, rather than a stable component of one’s preference function122. This hypothesis is weakened, however, by at least two sources of evidence. First, the fact that the relationship between behavioural and neural loss aversion holds even in resting-state brain activity, in the same striatal and insular regions previously found active when making choices during fMRI scanning46. Second, neurostructural evidence shows that individual differences in LA are correlated with GM volume in structures involved in somatosensory and affective processing such as insula26,123, alongside amygdala and striatum9,124,125. The present evidence on WM organization complements these previous findings, thereby strengthening the view that LA represents a stable neuro-cognitive component of one’s behavioural attitude in decision-making under risk.

The implications of this hypothesis are clearly shown by the ubiquity of LA, that has been reported regardless of one’s professional group (e.g., expert traders126 or taxi drivers127) and age (i.e., in adolescent, adult and elderly individuals128,129), and even in non-human species such as capuchin monkeys130. Observing a neuro-structural basis of LA fits with its stability over time, in turn making its degree a reliable measure of an individual’s decision-making and behavioural attitude6. This is even more relevant if one considers that LA is negatively associated with psychological well-being131, which might relate to the abnormal LA degree reported in several clinical conditions such as alexithymia132, depression with suicide attempts133, schizophrenia134,135,136 and substance addiction137. Therefore, unveiling the neurobiological bases of LA is important not only to gain insights into the processes underlying decision-making under risk, but also to delve into its impact in clinical populations138, and to envision innovative treatments aimed at improving patients’ quality of life, such as neurostimulation protocols targeting its key neural correlates139,140.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Machina, M. J. Decision-making in the presence of risk. Science 236 (4801), 537–543 (1987).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 1979:47:263–291 (1979).

Arioli, M. et al. Neural bases of loss aversion when choosing for oneself versus known or unknown others. Cereb. Cortex. 33 (11), 7120–7135 (2023).

Molins, F. & Serrano, M. A. Bases Neurales de La aversión a Las pérdidas En contextos económicos: revisión sistemática según Las directrices PRISMA. Revista De Neurologia. 68 (2), 47–58 (2019).

Walasek, L. & Stewart, N. How to make loss aversion disappear and reverse: tests of the decision by sampling origin of loss aversion. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144 (1), 7 (2015).

Sokol-Hessner, P. & Rutledge, R. B. The psychological and neural basis of loss aversion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28 (1), 20–27 (2019).

Ruggeri, K. et al. Replicating patterns of prospect theory for decision under risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4 (6), 622–633 (2020).

Brown, A. L., Imai, T., Vieider, F. M. & Camerer, C. F. Meta-analysis of empirical estimates of loss aversion. J. Econ. Lit. 62 (2), 485–516 (2024).

Canessa, N. et al. The functional and structural neural basis of individual differences in loss aversion. J. Neurosci. 33 (36), 14307–14317 (2013).

Sokol-Hessner, P., Hartley, C. A., Hamilton, J. R. & Phelps, E. A. Interoceptive ability predicts aversion to losses. Cogn. Emot. 29 (4), 695–701 (2015).

Sokol-Hessner, P., Camerer, C. F. & Phelps, E. A. Emotion regulation reduces loss aversion and decreases amygdala responses to losses. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 8 (3), 341–350 (2013).

Bouteska, A. & Regaieg, B. Loss aversion, overconfidence of investors and their impact on market performance evidence from the US stock markets. J. Econ. Finance Administrative Sci. 25 (50), 451–478 (2020).

Johnson, E. J. & Goldstein, D. G. Defaults and donation decisions. Transplantation 78 (12), 1713–1716 (2004).

Klapper, D., Ebling, C. & Temme, J. Another look at loss aversion in brand choice data: can we characterize the loss averse consumer? Int. J. Res. Mark. 22 (3), 239–254 (2005).

Nie, W., Bo, H., Liu, J. & Li, T. Influence of loss aversion and income effect on consumer food choice for food safety and quality labels. Front. Psychol. 12, 711671 (2021).

Rick, S. Losses, gains, and brains: neuroeconomics can help to answer open questions about loss aversion. J. Consumer Psychol. 21 (4), 453–463 (2011).

Aupperle, R. L., Melrose, A. J., Francisco, A., Paulus, M. P. & Stein, M. B. Neural substrates of approach-avoidance conflict decision‐making. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 36 (2), 449–462 (2015).

Pessiglione, M. & Delgado, M. R. The good, the bad and the brain: neural correlates of appetitive and aversive values underlying decision making. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 5, 78–84 (2015).

Tom, S. M., Fox, C. R., Trepel, C. & Poldrack, R. A. The neural basis of loss aversion in decision-making under risk. Science 315 (5811), 515–518 (2007).

Charpentier, C. J., Martino, B. D., Sim, A. L., Sharot, T. & Roiser, J. P. Emotion-induced loss aversion and striatal-amygdala coupling in low-anxious individuals. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 11 (4), 569–579 (2016).

Croxson, P. L., Walton, M. E., O’Reilly, J. X., Behrens, T. E. & Rushworth, M. F. Effort-based cost–benefit valuation and the human brain. J. Neurosci. 29 (14), 4531–4541 (2009).

Mansouri, F. A. et al. Direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex modulates error-induced behavioral adjustments. Eur. J. Neurosci. 44 (2), 1856–1869 (2016).

Xu, P., Van Dam, N. T., van Tol, M. J., Shen, X., Cui, Z., Gu, R., Luo, Y. J. Amygdala–prefrontal connectivity modulates loss aversion bias in anxious individuals. Neuroimage, 218, 116957. (2020).

Dreher, J. C. Sensitivity of the brain to loss aversion during risky gambles. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11 (7), 270–272 (2007).

Tanaka, S. C., Yamada, K., Yoneda, H. & Ohtake, F. Neural mechanisms of gain–loss asymmetry in Temporal discounting. J. Neurosci. 34 (16), 5595–5602 (2014).

Li, C., Wang, X. Q., Wen, C. H. & Tan, H. Z. Association of degree of loss aversion and grey matter volume in superior frontal gyrus by voxel-based morphometry. Brain Imaging Behav. 14, 89–99 (2020).

De Martino, B., Camerer, C. F. & Adolphs, R. Amygdala damage eliminates monetary loss aversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (8), 3788–3792 (2010).

Markett, S., Heeren, G., Montag, C., Weber, B. & Reuter, M. Loss aversion is associated with bilateral Insula volume. A voxel based morphometry study. Neurosci. Lett. 619, 172–176 (2016).

Gelskov, S. V., Henningsson, S., Madsen, K. H., Siebner, H. R. & Ramsøy, T. Z. Amygdala signals subjective appetitiveness and aversiveness of mixed gambles. Cortex 66, 81–90 (2015).

Yacubian, J. et al. Dissociable systems for gain-and loss-related value predictions and errors of prediction in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 26 (37), 9530–9537 (2006).

Chib, V. S., De Martino, B., Shimojo, S. & O’Doherty, J. P. Neural mechanisms underlying Paradoxical performance for monetary incentives are driven by loss aversion. Neuron 74 (3), 582–594 (2012).

Alfano, V., Longarzo, M., Aiello, M., Soricelli, A. & Cavaliere, C. Cerebral microstructural abnormalities in impulsivity: a magnetic resonance study. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 346–354 (2021).

Hampton, W. H., Alm, K. H., Venkatraman, V., Nugiel, T. & Olson, I. R. Dissociable frontostriatal white matter connectivity underlies reward and motor impulsivity. Neuroimage 150, 336–343 (2017).

Teti Mayer, J., Compagne, C., Nicolier, M., Grandperrin, Y., Chabin, T., Giustiniani,J., & Gabriel, D. Towards a functional neuromarker of impulsivity: feedback-related brain potential during risky decision-making associated with self-reported impulsivity in a non-clinical sample. Brain sci., 11(6), 671. (2021).

van den Bos, W., Rodriguez, C. A., Schweitzer, J. B. & McClure, S. M. Connectivity strength of dissociable striatal tracts predict individual differences in Temporal discounting. J. Neurosci. 34 (31), 10298–10310 (2014).

Han, S. D. et al. White matter correlates of Temporal discounting in older adults. Brain Struct. Function. 223, 3653–3663 (2018).

Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Levens, S. M., Perry, L. M., Dougherty, R. F. & Knutson, B. Frontostriatal white matter integrity mediates adult age differences in probabilistic reward learning. J. Neurosci. 32 (15), 5333–5337 (2012).

D’Alessandro, M., Gallitto, G., Greco, A. & Lombardi, L. A joint modelling approach to analyze risky decisions by means of diffusion tensor imaging and behavioural data. Brain Sci. 10 (3), 138 (2020).

Kohno, M., Morales, A. M., Guttman, Z. & London, E. D. A neural network that links brain function, white-matter structure and risky behavior. Neuroimage 149, 15–22 (2017).

Sasson, E., Doniger, G. M., Pasternak, O. & Assaf, Y. Structural correlates of memory performance with diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 50 (3), 1231–1242 (2010).

Shen, K. K. et al. Structural core of the executive control network: A high angular resolution diffusion MRI study. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 41 (5), 1226–1236 (2020).

Ribeiro, M., Yordanova, Y. N., Noblet, V., Herbet, G. & Ricard, D. White matter tracts and executive functions: a review of causal and correlation evidence. Brain 147 (2), 352–371 (2024).

Thams, F., Li, S. C., Flöel, A. & Antonenko, D. Functional connectivity and microstructural network correlates of interindividual variability in distinct executive functions of healthy older adults. Neuroscience 526, 61–73 (2023).

Wallace, E. J., Mathias, J. L. & Ward, L. The relationship between diffusion tensor imaging findings and cognitive outcomes following adult traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.. 92, 93–103 (2018).

Zheng, Z. et al. DTI correlates of distinct cognitive impairments in parkinson’s disease. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 35 (4), 1325–1333 (2014).

Canessa, N. et al. Neural markers of loss aversion in resting-state brain activity. NeuroImage 146, 257–265 (2017).

Sokol-Hessner, P. et al. Thinking like a trader selectively reduces individuals’ loss aversion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(13), 5035–5040. (2009).

Yeh, F. C., Panesar, S., Fernandes, D., Meola, A., Yoshino, M., Fernandez-Miranda,J. C., Verstynen, T. (2018). Population-averaged atlas of the macroscale human structural connectome and its network topology. Neuroimage, 178, 57–68.

Yeh, F. C., Badre, D. & Verstynen, T. Connectometry: a statistical approach Harnessing the analytical potential of the local connectome. Neuroimage 125, 162–171 (2016).

Yeh, F. C. & Tseng, W. Y. I. NTU-90: a high angular resolution brain atlas constructed by q-space diffeomorphic reconstruction. Neuroimage 58 (1), 91–99 (2011).

Yeh, F. C., Liu, L., Hitchens, T. K. & Wu, Y. L. Mapping immune cell infiltration using restricted diffusion MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 77 (2), 603–612 (2017).

Yeh, F. C., Vettel, J. M., Singh, A., Poczos, B., Grafton, S. T., Erickson, K. I., Verstynen, T. D. Quantifying differences and similarities in whole-brain white matter architecture using local connectome fingerprints. PLoS Comput. Biol., 12(11), e1005203. (2016).

Yeh, F. C., Verstynen, T. D., Wang, Y., Fernández-Miranda, J. C. & Tseng, W. Y. I. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PloS One, 8(11), e80713. (2013).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat., 1165–1188 (2001).

Zhang, H., Schneider, T., Wheeler-Kingshott, C. A. & Alexander, D. C. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 61 (4), 1000–1016 (2012).

Wu, E. X. & Cheung, M. M. MR diffusion kurtosis imaging for neural tissue characterization. NMR Biomed. 23 (7), 836–848 (2010).

Carbó-Valverde, S., Martín-Ríos, R. & Rodríguez-Fernández, F. Exploring neuroanatomy and neuropsychology in digital financial decision-making: betrayal aversion and risk behavior. Brain Imaging Behav., 1–8. (2025).

Amaral, D. & Lavenex, P. Hippocampal neuroanatomy. In The Hippocampus Book (eds Andersen, P. et al.) 37–114 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

Senova, S., Fomenko, A., Gondard, E. & Lozano, A. M. Anatomy and function of the fornix in the context of its potential as a therapeutic target. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 91 (5), 547–559 (2020).

Ji, J. & Maren, S. Lesions of the entorhinal cortex or fornix disrupt the context-dependence of fear extinction in rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 194 (2), 201–206 (2008).

Degroot, A. & Treit, D. Anxiety is functionally segregated within the septo-hippocampal system. Brain Res. 1001 (1–2), 60–71 (2004).

Benear, S. L., Ngo, C. T. & Olson, I. R. Dissecting the fornix in basic memory processes and neuropsychiatric disease: a review. Brain Connect. 10 (7), 331–354 (2020).

Maldonado, I. L., de Matos, V. P., Cuesta, T. A. C., Herbet, G. & Destrieux, C. The human cingulum: from the limbic tract to the connectionist paradigm. Neuropsychologia 144, 107487 (2020).

Kamali, A., Khalaj, K., Ali, A., Khalaj, F., Kokash, D., Gonzalez, A. R., Hasan,K. M. Direct parieto-occipital connectivity of the amygdala via the parahippocampal segment of the cingulum bundle. Neuroradiol. J., (2025).

Catani, M., Dell’Acqua, F. & de Thiebaut, M. A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.. 37, 1724–1737 (2013).

Husain, M. & Schott, J. M. Oxford Textbook of Cognitive Neurology and Dementia (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Nieuwenhuys, R., Voogd, J. & Huijzen, C. The Human Central Nervous System 4th edn (Springer, 2008).

Bubb, E. J., Metzler-Baddeley, C. & Aggleton, J. P. The cingulum bundle: Anatomy, function, and dysfunction. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 92, 104–127 (2018).

Catani, M. & de Thiebaut, M. A diffusion tensor imaging tractography atlas for virtual in vivo dissections. Cortex 44, 1105–1132 (2008).

Goldstein, A., Covington, B. P., Mahabadi, N. & Mesfn, F. B. Neuroanatomy, Corpus Callosum (StatPearls Publishing, 2022).

Gobbi, C. et al. Forceps minor damage and co-occurrence of depression and fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 20 (12), 1633–1640. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514530022 (2014).

Riverol, M. et al. Forceps minor region signal abnormality ears of the lynx: an early MRI finding in spastic paraparesis with thin corpus callosum and mutations in the Spatacsin gene (SPG11) on chromosome 15. J. Neuroimaging. 19 (1), 52–60 (2009).

Porcu, M. et al. Correlation of cognitive reappraisal and the microstructural properties of the forceps minor: A deductive exploratory diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain Topogr. 37 (1), 63–74 (2024).

Zarei, M. et al. Changes in Gray matter volume and white matter microstructure in adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 70 (11), 1083–1090 (2011).

Muller, J. & Roberts, J. E. Memory and attention in obsessive–compulsive disorder: a review. J. Anxiety Disord. 19 (1), 1–28 (2005).

Szechtman, H., Eckert, M. J., Tse, W. S., Boersma, J. T., Bonura, C. A., McClelland,J. Z., Eilam, D. Compulsive checking behavior of quinpirole-sensitized rats as an animal model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): form and control. BMC neuroscience, 2, 1–15. (2001).

Straathof, M., Blezer, E. L., van Heijningen, C., Smeele, C. E., van der Toorn, A.,Buitelaar, J., & Dijkhuizen, R. M. Structural and functional MRI of altered brain development in a novel adolescent rat model of quinpirole-induced compulsive checking behavior.Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol., 33, 58–70. (2020).

He, X. et al. Altered frontal interhemispheric and fronto-limbic structural connectivity in unmedicated adults with obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 39 (2), 803–810 (2018).

Haghshomar, M., Mirghaderi, S. P., Shobeiri, P., James, A. & Zarei, M. White matter abnormalities in paediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. Brain Imaging Behav. 17 (3), 343–366 (2023).

Burzynska, A. Z. et al. A scaffold for efficiency in the human brain. J. Neurosci. 33 (43), 17150–17159 (2013).

Xie, S. et al. Voxel-based detection of white matter abnormalities in mild alzheimer disease. Neurology 66 (12), 1845–1849 (2006).

Surova, Y. et al. Alteration of putaminal fractional anisotropy in parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal diffusion kurtosis imaging study. Neuroradiology 60, 247–254 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Schuff, N., Du, A. T., Rosen, H. J., Kramer, J. H., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Weiner, M. W. White matter damage in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease measured by diffusion MRI. Brain, 132(9), 2579–2592. (2009).

Ochsner, K. N. & Gross, J. J. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9 (5), 242–249 (2005).

Nakajima, R., Kinoshita, M., Shinohara, H. & Nakada, M. The superior longitudinal fascicle: reconsidering the fronto-parietal neural network based on anatomy and function. Brain Imaging Behav. 14, 2817–2830 (2020).

Makris, N. et al. Segmentation of subcomponents within the superior longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo, DT-MRI study. Cerebral cortex, 15(6), 854–869., (2019). Bases neurales de la aversión a las pérdidas en contextos económicos: revisión sistemática según las directrices PRISMA. Revista de neurologia, 68(2), 47–58. (2005).

Xu, J. et al. White matter integrity and behavioural activation in healthy subjects. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21275 (2012).

Henriques, J. B. & Davidson, R. J. Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition Emot. 14 (5), 711–724 (2000).

Murphy, M. L. & Frodl, T. Meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies shows altered fractional anisotropy occurring in distinct brain areas in association with depression. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord.. 1, 1–12 (2011).

Koch, K., Wagner, G., Schachtzabel, C., Schultz, C. C., Güllmar, D., Reichenbach,J. R., Schlösser, R. G. Association between white matter fiber structure and reward-related reactivity of the ventral striatum. Hum. Brain Mapp., 35(4),1469–1476. (2014).

Martino, J., Vergani, F., Robles, S. G. & Duffau, H. New insights into the anatomic dissection of the Temporal stem with special emphasis on the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus: implications in surgical approach to left mesiotemporal and temporoinsular structures. Operative Neurosurg. 66 (3), ons4–ons12 (2010).

Rolls, E. T. Emotion, motivation, decision-making, the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala. Brain Struct. Funct.. 228 (5), 1201–1257 (2023).

Rudrauf, D. et al. Rapid interactions between the ventral visual stream and emotion-related structures rely on a two-pathway architecture. J. Neurosci. 28 (11), 2793–2803 (2008).

Schmahmann, J. D. et al. Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography. Brain 130 (3), 630–653 (2007).

Balleine, B. W., Delgado, M. R. & Hikosaka, O. The role of the dorsal striatum in reward and decision-making. J. Neurosci. 27 (31), 8161–8165 (2007).

Smittenaar, P., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Mohammadi, S., Weiskopf, N. & Dolan, R. J. Local striatal reward signals can be predicted from corticostriatal connectivity. Neuroimage 159, 9–17 (2017).

Camara, E., Rodriguez-Fornells, A. & Münte, T. F. Microstructural brain differences predict functional hemodynamic responses in a reward processing task. J. Neurosci. 30 (34), 11398–11402 (2010).

Catani, M. et al. Short frontal lobe connections of the human brain. Cortex 48, 273–291 (2012).

Dick, A. S., Garic, D., Graziano, P. & Tremblay, P. The frontal Aslant tract (FAT) and its role in speech, Language and executive function. Cortex 111, 148–163 (2019).

Burkhardt, E., Kinoshita, M. & Herbet, G. Functional Anatomy of the Frontal Aslant Tract and Surgical Perspectives. J. Neurosurg. Sci., (2021).

Tagliaferri, M., Giampiccolo, D., Parmigiani, S., Avesani, P. & Cattaneo, L. Connectivity by the frontal Aslant tract (FAT) explains local functional specialization of the superior and inferior frontal gyri in humans when choosing predictive over reactive strategies: a tractography-guided TMS study. J. Neurosci. 43 (41), 6920–6929 (2023).

Loe, I. M., Adams, J. N. & Feldman, H. M. Executive function in relation to white matter in preterm and full term children. Front. Pead. 6, 418 (2019).

Hofer, S. & Frahm, J. Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited—comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 32 (3), 989–994 (2006).

Abed Rabbo, F., Koch, G., Lefèvre, C. & Seizeur, R. Stereoscopic visual area connectivity: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 40, 1197–1208 (2018).

Krogsrud, S. K. et al. Development of white matter microstructure in relation to verbal and visuospatial working memory—a longitudinal study. Plos One. 13 (4), e0195540 (2018).

Herbet, G., Zemmoura, I. & Duffau, H. Functional anatomy of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus: from historical reports to current hypotheses. Front Neuroanat. 12, 77 (2018).

Latini, F. New insights in the limbic modulation of visual inputs: the role of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus and the Li-Am bundle. Neurosurg. Rev. 38 (1), 179–190 (2015).

Panesar, S. S., Yeh, F. C., Jacquesson, T., Hula, W. & Fernandez-Miranda, J. C. A quantitative tractography study into the connectivity, segmentation and laterality of the human inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Front Neuroanat. 12, 47 (2018).

Tükel, R. et al. Evidence for alterations of the right inferior and superior longitudinal fasciculi in patients with social anxiety disorder. Brain Res. 1662, 16–22 (2017).

Liao, W., Qiu, C., Gentili, C., Walter, M., Pan, Z., Ding, J., Chen, H. Altered effective connectivity network of the amygdala in social anxiety disorder:a resting-state FMRI study. PloS one, 5(12), e15238. (2010).

Herting, M. M., Schwartz, D., Mitchell, S. H. & Nagel, B. J. Delay discounting behavior and white matter microstructure abnormalities in youth with a family history of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(9), 1590–1602. (2010).

Choo, I. H. et al. Posterior cingulate cortex atrophy and regional cingulum disruption in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 31 (5), 772–779 (2010).

Redish, A. D. & Mizumori, S. J. Memory and decision making. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 117, 1 (2015).

Kilpatrick, L. A. & Cahill, L. Amygdala modulation of parahippocampal and frontal regions during emotionally influenced memory storage. NeuroImage, 20(4), 2091–2099. (2003).

Pohlack, S. T., Nees, F., Ruttorf, M., Schad, L. R. & Flor, H. Activation of the ventral striatum and of the parahippocampal gyrus predicts long-term survival of fear memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 97 (3), 312–319 (2012).

Smith, A. P., Stephan, K. E., Rugg, M. D. & Dolan, R. J. Task and content modulate amygdala-hippocampal connectivity in emotional retrieval. Neuron 49 (4), 631–638 (2006).

Vogt, B. A. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 (7), 533–544 (2005).

Beaulieu, C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system–a technical review. NMR Biomedicine: Int. J. Devoted Dev. Application Magn. Reson. Vivo. 15 (7-8), 435–455 (2002).

Song, S. K. et al. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage 17 (3), 1429–1436 (2002).

Ricchi, M. et al. Connectivity related to major brain functions in alzheimer disease progression: microstructural properties of the cingulum bundle and its subdivision using diffusion-weighted MRI. Eur. Radiol. Experimental. 9 (1), 32 (2025).

Tan, Y., Yan, R., Gao, Y., Zhang, M. & Northoff, G. Spatial-topographic nestedness of interoceptive regions within the networks of decision making and emotion regulation: combining ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis. NeuroImage 260, 119500 (2022).

Camerer, C. Three cheers—psychological, theoretical, empirical—for loss aversion. J. Mark. Res. 42 (2), 129–133 (2005).

Arioli, M. et al. Morphometric evidence of a U‐shaped relationship between loss aversion and posterior insular/somatosensory cortical features. Hum. Brain Mapp. 46(10), e70274 (2025).

Canessa, N. et al. Understanding others’ regret: a f MRI study. PloS One 4(10), e7402 (2009).

Canessa, N., Motterlini, M., Alemanno, F., Perani, D. & Cappa, S. F. Learning from other people’s experience: A neuroimaging study of decisional interactive-learning. NeuroImage 55 (1), 353–362 (2011).

Haigh, M. S. & List, J. A. Do professional traders exhibit myopic loss aversion? An experimental analysis. J. Finance. 60 (1), 523–534 (2005).

Camerer, C., Babcock, L., Loewenstein, G. & Thaler, R. Labor Supply of New York City Cabdrivers: One Day at a Time. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, In Memory of Amos Tversky (1937–1996)), 407–441. (1997).

Barkley-Levenson, E. E., Van Leijenhorst, L. & Galván, A. Behavioral and neural correlates of loss aversion and risk avoidance in adolescents and adults. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 3, 72–83 (2013).

Rutledge, R. B., Smittenaar, P., Zeidman, P., Brown, H. R., Adams, R. A., Lindenberger,U., Dolan, R. J. Risk taking for potential reward decreases across the lifespan. Current Biol., 26(12), 1634–1639. (2016).

Chen, M. K., Lakshminarayanan, V. & Santos, L. R. How basic are behavioral biases? Evidence from capuchin monkey trading behavior. J. Polit. Econ. 114 (3), 517–537 (2006).

Koan, I., Nakagawa, T., Chen, C., Matsubara, T., Lei, H., Hagiwara, K., & Nakagawa, S. The Negative association between positive psychological wellbeing and loss aversion. Front. Psychol., 12, 641340. (2021).

Bibby, P. A. & Ferguson, E. The ability to process emotional information predicts loss aversion. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 51 (3), 263–266 (2011).

Baek, K., Kwon, J., Chae, J. H., Chung, Y. A., Kralik, J. D., Min, J. A., Jeong,J. Heightened aversion to risk and loss in depressed patients with a suicide attempt history. Scientific reports, 7(1), 11228. (2017).

Currie, J. et al. Schizophrenia illness severity is associated with reduced loss aversion. Brain Res. 1664, 9–16 (2017).

Currie, J., Waiter, G. D., Johnston, B., Feltovich, N. & Steele, J. D. Blunted neuroeconomic loss aversion in schizophrenia. Brain Res. 1789, 147957 (2022).

Canessa, N., Iozzino, L., Andreose, S., Castelletti, L., Conte, G., Dvorak, A., de Girolamo, G. RISK aversion in Italian forensic and non-forensic patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. PloS One, 18(7), e0289152. (2023).

Meade, C. S. et al. Cocaine and HIV are independently associated with neural activation in response to gain and loss valuation during economic risky choice. Addict. Biol. 23 (2), 796–809 (2018).

Takahashi, H., Fujie, S., Camerer, C., Arakawa, R., Takano, H., Kodaka, F., Suhara,T. Norepinephrine in the brain is associated with aversion to financial loss. Mol. Psychiatr., 18(1), 3–4. (2013).

Gorrino, I., Canessa, N. & Mattavelli, G. Testing the effect of high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation of the insular cortex to modulate decision-making and executive control. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 17, 1234837 (2023).

Mattavelli, G., Lo Presti, S., Tornaghi, D. & Canessa, N. High-definition transcranial direct current stimulation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex modulates decision-making and executive control. Brain Struct. Function. 227 (5), 1565–1576 (2022).

Funding

This research was partially supported by the “Ricerca Corrente” funding scheme of the Italian Ministry of Health to ICS Maugeri, and the “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027” funding scheme of the Italian Ministry of University and Research to IUSS Pavia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maria Arioli (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing-original draft), Andrea Braga (Formal analysis, Writing-review&editing), Zaira Cattaneo (Investigation, Resources), Giulia Mattavelli (Investigation, Methodology), Paolo Poggi (Investigation, Resources), and Nicola Canessa (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-original draft).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arioli, M., Braga, A., Cattaneo, Z. et al. Diffusion connectometry reveals white matter substrates of individual differences in loss aversion. Sci Rep 15, 44291 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27901-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27901-1