Abstract

Foreign object damage (FOD) in Inconel 718 base metal(BM) and welded joints(WJ) was investigated using pendulum impact testing. The effects of impact energy on damage morphology, microstructure, and fatigue performance were analyzed. The results show that: 1. The fatigue life and hardness inherent in WJ are higher than those of the BM, primarily due to grain refinement and the presence of precipitated phases at grain boundaries; 2. Macroscopically, the damage notches exhibit a V—shape. Their dimensions increase with the rise in impact energy. However, under the same energy level, the damage dimensions of WJ are smaller than those of the BM; 3. Microscopically, the damage of the BM mainly manifests as crack initiation at the carbide interfaces. In contrast, a large number of holes and microcracks form at the precipitated phases in WJ; 4. Under low—energy impact, WJ possess a higher fatigue life than the BM. This is attributed to their smaller damage dimensions and finer grain structure. Nevertheless, under high—energy impact, the numerous voids and cracks generated inside WJ lead to a sharp decline in their fatigue life, which even become lower than that of the BM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inconel 718 alloy is a Ni–Cr–Fe-based wrought superalloy. Its excellent high-temperature fatigue strength and creep resistance originate from the dispersion strengthening effect of γ'' phase (Ni₃Nb) and γ' phase (Ni₃(Al,Ti)) in the austenite matrix, as well as the grain boundary regulation function of δ phase. Consequently, it is widely used in manufacturing key components of aero-engines, such as compressor blades, casings and bladed disks1,2,3. Welding technology serves as one of the primary manufacturing and repair techniques for wrought superalloy components. Welded structures offer advantages including reduced weight, enhanced efficiency, and high reliability, leading to their extensive utilization within aero-engine assemblies4. However, during the solidification process of the welding procedure, niobium tends to segregate, which promotes the formation of niobium carbide (NbC) and Laves phase, and may induce hot cracking due to the liquation of these phases5. The significant difference in microstructure between this zone and the base metal makes welded joints the weakest link in the fatigue performance of the entire structure6.

During service, aero-engines are susceptible to ingesting foreign hard objects such as sand particles and metal fragments, leading to foreign object damage (FOD), which exhibits significant randomness and unpredictability7. The ingestion of large foreign objects can trigger cascade failure events, potentially damaging critical components including combustors and turbines. Under cyclic loading, notches and tears induced by FOD compromise surface integrity, triggering fatigue crack initiation and propagation that significantly degrade the fatigue resistance of materials and structures. Current research on FOD has identified four primary damage mechanisms during impact events8:1) Geometric stress concentration at impact-induced notches; 2) Microstructural damage induced by notch plastic deformation from FOD;3) Micro-geometric discontinuity damage surrounding notches;4) Damage mechanisms driven by residual stress fields. Spanrad et al9 and Zhu et al10 employed gas gun testing to investigate the influence of FOD on fatigue crack behavior in titanium alloys. Their results demonstrated that the damaged regions exhibited features including notch indentations, material loss, material shearing, shear bands, and microcracks. Fatigue cracks were found to initiate at micro-notches along the crater rim and at the root of notches where shear bands and microcracks formed. Arcieri et al11 studied the fatigue limit loads of titanium alloys containing V-shaped notches, revealing that a smaller net cross-sectional area at the notch results in a lower fatigue limit load. Lin et al12 examined the effect of FOD on fatigue crack propagation in titanium alloys following laser shock peening (LSP). Their findings indicated that specimens subjected to both LSP and FOD exhibited lower crack initiation rates and slower early-stage fatigue crack growth rates compared to specimens with FOD alone. Fleury et al13 proposed a methodology for assessing the impact of surface damage on the fatigue life of nickel-based superalloys. Their results suggested that careful consideration of the residual stresses surrounding the damage zone can improve the accuracy of fatigue life predictions for damaged components. Jia et al14 investigated the effect of FOD on the high-cycle fatigue (HCF) performance of GH4169 alloy. The study demonstrated that the fatigue strength of damaged specimens decreased with increasing damage depth, and that the presence of impact-induced cracks and voids at the notch root led to premature HCF crack initiation.

At present, research on the characteristics of FOD and its influence on fatigue strength after damage still has significant limitations: existing studies mainly focus on the base metal, while systematic analysis of the effect of FOD on the microstructure damage mechanism of welded joints is lacking. Therefore, this study employs Inconel 718 as the test material. Microbeam plasma arc welding was utilized to fabricate the joints. The foreign object damage process was simulated using pendulum impact testing, and subsequently, bending vibration fatigue tests were conducted on the FOD specimens. The research investigates the influence of macro- and microstructural damage morphology features, induced by impact in both the BM and WJ, on fatigue life.

Experimental procedure

This study employed annealed Inconel 718 alloy plates manufactured by ATI (Allegheny Technologies Incorporated), USA, complying with the AMS 5596 M standard. The welding wire was Inconel 718 filler wire supplied by ASTROLITE ALLOYS, USA, conforming to the AMS 5832 J standard. The chemical compositions of the Inconel 718 alloy plate and welding wire are presented in Table 1. Welding-based additive manufacturing of the superalloy sheet was conducted using the independently developed BW-100 Microbeam Pulsed Plasma Arc Welding Robotic System for Blade Repair, with the welding process parameters employed for fabricating the WJ detailed in Table 2.

To eliminate welding residual stresses, the welded specimens were subjected to vacuum heat treatment. The specific process was as follows: holding at 760 °C for 2 h, followed by holding at 620 °C for 4 h. Standard fatigue specimens were sectioned from the welded plates for fatigue testing, with the detailed sampling method and standard fatigue specimens illustrated in Fig. 1.

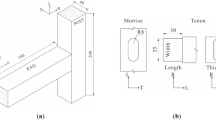

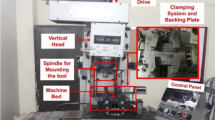

A JB-W300YZ microcomputer-controlled V-notch pendulum impact tester was employed to simulate foreign object damage (FOD) notches at identical locations in the weld zone and BM of the fatigue specimens. The pendulum was fabricated from 45 steel, featuring a V-shaped included angle of 60°, a fillet radius of 0.1 mm, an impact angle of 90°, and a surface roughness of Ra0.8. The simulation adopted the impact energy equivalence method, where the potential energy of the pendulum was equated to the kinetic energy potentially achieved when foreign objects impact the blade. Impact energies of 1 J, 3 J, 5 J, and 7 J were applied respectively, and the impact mechanism is depicted in Fig. 2.

Bending fatigue tests were conducted on specimens containing FOD using a cantilever bending fatigue testing machine. Five amplitude levels (6 mm, 7 mm, 8 mm, 9 mm, and 10 mm) were set for the tests, with three repeated tests performed at each amplitude. Meanwhile, the strain values at the bending position of the specimens under the corresponding amplitudes were measured by a DIC device. The specimen fixture consisted of a fixed end and a cantilever end, with bearing assemblies integrated at both ends to effectively eliminate tensile/compressive stresses and torsional stresses generated during the fatigue tests, ensuring the specimens were solely subjected to cyclic bending stress. The fatigue tests were performed at a frequency of 5 Hz with a stress ratio R = −1 in ambient air at room temperature, and the motion trajectory of the specimens is shown in Fig. 3. Microhardness measurements of the superalloy WJ were conducted using a TMVT-1 digital microhardness tester, with a test load of 9.8N, a dwell time of 10 s, and an indentation spacing of 0.2 mm.

For microstructural analysis, cross-sections of the WJ and notched specimens after impact were cut into dimensions of 20 × 20 × 2mm3. Sample preparation followed standard metallographic procedures: grinding sequentially with 240#, 400#, 800#, 1200#, and 2000# abrasive papers, followed by mirror polishing with 2.5 μm diamond paste in water. The specimens were then etched with a CuCl solution for 15 s to reveal the microstructures. A Stemi 508 stereomicroscope was used to characterize the dimensions and macroscopic morphology2 of the FOD notches. A ZEISS Sigma 300 scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed to observe the microstructural morphologies of the WJ, FOD notches, and fatigue fracture surfaces, with concurrent energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) was utilized to characterize the deformed microstructure of the specimens after impact, operating at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV with a step size of 0.25 μm, and the raw data were processed by AZtecCrystal 2.1 software.

Results and discussion

Microstructure of welded joints

The weld, after X-ray defect detection, revealed no defects such as porosity, cracks, or lack of fusion in the internal structure. The general microstructure of the WJ is shown in Fig. 4a, including the weld zone (WZ) (region (b) and (c)), heat-affected zone (HAZ) (region (d)), and BM (region (e)). The weld zone can be subdivided based on grain morphology into a surface layer of fine equiaxed grains (Fig. 4b) and an interior region of coarse columnar dendrites (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 4b, the equiaxed grain region exists at the weld surface, with a maximum thickness of 720 μm. And it can be seen in Fig. 4c that the dendrites grew perpendicular to the fusion line, with secondary dendrite arms developing on primary dendrite trunks. The BM exhibited an equiaxed austenitic microstructure with an average grain size of 19.5 μm, containing annealing twins (Fig. 4e). The heat-affected zone was narrow, measuring approximately 58–107 μm in width, and displayed an equiaxed austenitic structure with an average grain size of 28 μm. This represents a 43% increase in austenitic grain size compared to the BM (Fig. 4d). In addition, in the weld zone shown in Fig. 4b and c, elemental segregation at grain boundaries in both the equiaxed and dendritic regions led to the formation of abundant precipitates, exhibiting network-like and chain-like distributions, respectively. (Fig. 5) EDS analysis indicates that these precipitates are mainly Nb-rich and Mo-rich phases, which are inferred to be the γ″-Ni2(Nb,Mo) phase. Point scanning analysis of precipitates at different locations (Fig. 6) confirmed the presence of MC-type carbide particles within the precipitate phases. This result is consistent with the findings of existing studies. Wang et al15 found that a large number of γ″-Ni2(Nb,Mo) phases and MC carbides are precipitated in the weld during plasma arc welding of Inconel718.

Figure 7 presents the hardness measurement results of the WJ. The fusion zone exhibits higher hardness than the base material, with the central region reaching a peak hardness of 278.5 HV1. Hardness progressively decreases toward both sides, while the base material maintains an average hardness of 230.6 HV1. It is inferred that a large number of uniformly distributed γ″-Ni₃(Nb,Mo) phases precipitated in the weld zone after heat treatment, thereby enhancing the hardness of the WJ16.

Macroscopic damage morphology of FOD

Figure 8 illustrates the notch damage morphology of BM and WJ under different impact conditions, including side views and overall top views. The notch damage induced by various impact energies exhibits a V-shaped profile. Upon impact, material extrusion causes bulging on both sides of the notch, with a smooth and flat inner surface showing no signs of material detachment. As impact energy increases, plastic deformation and bulging severity gradually intensify. The WJ notch region displays obvious material stacking and wrinkling features. When the impact energy reaches 7 J, crack features appear at the notch sides of the joint. In contrast, the BM notch surface remains smooth and flat, free of significant wrinkling or crack features. The strengthening precipitates and carbide phases at grain boundaries in the WJ pin these boundaries, restricting slip along equiaxed and dendritic grain interfaces during deformation17. This mechanism promotes intragranular plastic deformation and induces strain twinning or dislocation-driven formation of pronounced stacking and folding features on the weld surface18 ultimately leading to crack initiation under high-energy impact.

The dimensions of the damaged notches were measured and analyzed, with Fig. 9 defining the dimensional parameters of the notches. The trend in Fig. 10 visually demonstrates the influence of impact energy on damage parameters. As the impact energy increases, both the notch width and depth gradually increase. Notably, the damaged notches in the WJ consistently exhibited smaller dimensions than those in the BM under identical impact energies. This phenomenon is attributed to elemental segregation within the WJ, which promotes the formation of additional strengthening γ″-Ni₃(Nb,Mo) phases, thereby increasing its hardness. Furthermore, the presence of fine equiaxed grains in the WJ enhances its strength, resulting in superior deformation resistance against external impact.

Microscopic damage morphology of FOD

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to observe the microstructural morphology of FOD notches (Fig. 11). The images reveal intensified plastic deformation in both WJ and BM notches with increasing impact energy, accompanied by increasingly flattened grain shapes. Cracks were observed along the notch edge of the BM under high-impact energy (Fig. 11e-1), with carbides embedded within these cracks. Due to their inherent brittleness, carbides fracture or detach from the matrix when impact energy exceeds either the carbide strength or the carbide-grain interfacial strength, facilitating void and crack initiation. Voids and cracks were identified in the WJ after impact. The void density increased with impact energy, predominantly nucleating near precipitates; a significant crack (~ 40 μm long) formed at 7 J impact energy (Fig. 11f-1). Compared to the BM, the WJ contains abundant precipitates. Upon impact loading, these precipitates impede dislocation motion near the notch region, causing dislocations to accumulate at grain boundaries. This dislocation pile-up generates stress concentration which, when exceeding the interfacial bonding strength of precipitates, immediately initiates void formation at precipitate interfaces19. Additionally, deformation incompatibility between precipitates and the matrix induces interfacial decohesion, creating further voids (Fig. 12a). Consequently, under identical impact energy, the WJ develops substantially more voids and microcracks than the BM. Schematic diagrams of the above mechanisms are shown in Fig. 12b.

The microstructural evolution at the notches of the BM and WJ under impact energies of 1 J, 3 J, and 7 J was characterized using EBSD technology, as shown in Fig. 13. With the increase in impact energy, the grains fracture and refine upon impact: the average grain size at the BM notch decreases from 22.8 to 16.2 μm, while that at the WJ notch drops from 18.6 to 2.9 μm. Since the WJ has a higher initial stored energy from welding, the stored energy further accumulates after the superposition of impact load, inducing dynamic recrystallization20 and resulting in a much higher degree of grain refinement in the WJ than in the BM.

Low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs) are generally defined as those with misorientation angles between 2° and 15°, while high-angle grain boundaries typically have misorientation angles greater than 15°; grain boundaries with misorientation angles less than 2° are generally not counted21. As can be seen from Fig. 12, with the increase in impact energy, the external impact causes a large number of dislocations to form inside the material, which in turn leads to the generation of more LAGBs to coordinate deformation, resulting in an increase in the proportion of LAGBs in both the BM and WJ. Dislocations inside the material undergo rearrangement and annihilation driven by the impact energy; meanwhile, microstructural adjustments such as dynamic recovery and grain boundary migration make the intragranular orientation tend to be uniform, leading to a decreasing trend in the average Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) values of both the BM and WJ.

Σ3 coherent grain boundaries are special grain boundaries with low interfacial energy and high stability22, and their proportions show opposite evolutionary trends in the BM and WJ: the proportion of Σ3 grain boundaries decreases in the BM but increases in the WJ. The BM initially has an equilibrium microstructure with a inherently high proportion of Σ3 grain boundaries; under energy impact, the intense interaction between dislocation movement and grain boundaries destroys the originally stable Σ3 grain boundaries, leading to a decrease in their proportion. In contrast, the WJ has initially unstable grain boundaries; high-energy impact triggers dynamic recrystallization and grain boundary migration. To reduce interfacial energy and improve structural stability, the grain boundaries reconstruct to form more Σ3 coherent grain boundaries, thus their proportion increases with the rise in impact energy.

Effect of FOD on fatigue life

The fatigue data of the specimens were statistically analyzed, the bending amplitude was converted into total strain, and fitting was performed using the Coffin-Manson formula. Figure 14 presents the bending fatigue life test results for undamaged specimens of the BM and the WJ. The reveal that the fatigue life of the BM ranges from 34.2 to 59.6% of that exhibited by the WJ. This phenomenon is attributed to the refined grain structure within the WJ. This refined structure significantly increases the number of grain boundaries encountered along the fatigue crack propagation path, causing frequent changes in crack direction during propagation, which consumes energy and thereby prolongs the fatigue life23. Furthermore, the uniformly distributed γ″-Ni2(Nb,Mo) phase in the WJ effectively hinders dislocation motion, thus delaying the accumulation of fatigue damage24.

Figure 15 shows the fatigue life test data of FOD specimens. The fatigue lives of the WJ and BM have decreased significantly after impact. When comparing the fatigue lives of the damaged WJ and BM, under impact energies of 1 J and 3 J, the damage depth and width at the BM notch are both greater than those at the WJ notch, resulting in more significant initial macroscopic damage, which further accelerates the crack initiation process. Although precipitated phases lead to more holes in the WJ, the WJ still shows higher fatigue life. This is due to the combined action of its lower initial damage and stronger microstructural crack resistance. Additionally, Nowell25 study has confirmed that notch depth is a major factor affecting fatigue strength.

However, for fatigue specimens with impact energies of 5 J and 7 J, the fatigue life reverses with changes in strain amplitude. At low strains, the fatigue life of the WJ is more sensitive to FOD, resulting in a lower fatigue life than the BM. At low strains, the number of fatigue cycles is large, and fatigue is dominated by crack initiation. The WJ contains numerous microscopic defects such as holes and cracks, which grow and coalesce rapidly under cyclic loading, easily becoming the starting points of fatigue cracks and accelerating fatigue crack initiation. The crack source effect of these microscopic defects exceeds the microstructural strengthening effect, thereby significantly reducing the fatigue life of the WJ. In specimens tested at high strains, fatigue is dominated by crack propagation, and the inhibition of crack propagation by the microstructure becomes the dominant factor. The extremely fine grains of the WJ (2.94 μm at 7 J) effectively hinder crack propagation through the grain boundary pinning effect. Moreover, the proportion of Σ3 grain boundaries in the WJ further increases, and the KAM value is lower, which further inhibits crack propagation. Eventually, this causes the fatigue life of the WJ to become higher than that of the BM again. It can be seen from the experimental results that the impact energy threshold determines the relationship between the degree of damage accumulation and the dominance of the microstructure.

Figure 16 displays macroscopic views of fatigue fracture surfaces in FOD specimens of BM and WJ. For the BM, fatigue origins primarily initiate at the notch tip, exhibiting relatively flat fracture surfaces. In contrast, WJ specimen fracture along the weld seam, with multiple fatigue origins present at both the notch tip and specimen surface. These fatigue origins propagate toward the specimen center at 45° angles. The fracture surfaces appear uneven with prominent tearing steps, where convergence ridges form due to non-coplanar coalescence of multiple crack fronts during propagation. FOD alters crack initiation mechanisms, accelerating crack nucleation and thereby reducing material fatigue life.

Figure 17 presents SEM images of fatigue fracture surfaces for undamaged WJ and BM. Figure 17a shows the fatigue initiation zone of the BM, where cracks propagate rapidly via slip-band jumping, forming river patterns radiating outward. Figure 17b depicts the fatigue initiation zone of the WJ, exhibiting intergranular fracture planes and quasi-cleavage steps during early crack propagation. Figure 17c displays the propagation zone of the BM, featuring numerous irregular parallel fatigue striations. Figure 17d illustrates the propagation zone of the WJ, containing abundant fatigue striations with fine straight secondary cracks and wider secondary cracks between them. Partial secondary cracks propagate parallel to striations, inducing crack deflection that extends the propagation path and prolongs fatigue life. Figure 17e and f show the final rupture zones of the BM and WJ, respectively. The BM rupture zone exhibits extensive dimples, while the WJ rupture zone reveals voids containing carbides. These fracture features indicate greater brittleness in the WJ.

Figure 18 shows SEM images of fatigue fracture surfaces for FOD specimens. Figure 18a reveals secondary cracks near the notch in the BM, while Fig. 18b displays numerous dimples in the WJ notch vicinity. Figure 18c and d depict the propagation zone of the BM, exhibiting fatigue striations and secondary cracks. These secondary cracks consume propagation energy, reducing crack growth rates. With increasing impact energy, striation spacing widens and secondary cracks enlarge. Figure 18e exhibits large cleavage planes characteristic of brittle fracture, alongside fatigue striations and secondary cracks. Carbide particles are observed at secondary crack sites in Fig. 18f. Carbides readily undergo interfacial decohesion from the matrix, acting as crack initiation sites and propagation paths26. Additionally, grain-boundary carbides induce inhomogeneous slip in adjacent grains, altering crack growth rates and serving as nucleation points for fatigue cracks or secondary cracks under cyclic stress. Figure 18g and h present final rupture zones, where both BM and WJ show dimples containing carbide particles.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The WJ microstructure comprises fine equiaxed grains and coarse dendritic zones. Nb/Mo-rich phases and minor carbides precipitate along grain boundaries, resulting in higher hardness (peak: 278.5 HV1) than the BM.

-

(2)

Macroscopically, damage notches exhibit V-shaped profiles with smooth interiors and slight peripheral protrusions. As the impact energy increases, the size of FOD increases. Under the same impact energy, the damage size of the WJ is smaller than that of the BM.

-

(3)

Impact-induced cracks and voids in the BM initiate primarily at carbide interfaces, whereas voids/cracks in the WJ nucleate predominantly at precipitate interfaces. The WJ exhibits higher void/crack density and greater susceptibility to large cracks than the BM at equivalent impact energies.

-

(4)

The fatigue life exhibits a reversal between low and high impact energies. At 1 J and 3 J, the fatigue life of the welded joint is relatively high; however, at 5 J and 7 J, its fatigue life is lower than that of the base metal.

Limitations

In this study, the pendulum method was employed to conduct FOD simulation tests. This pendulum method is primarily applicable to single low-velocity impact scenarios involving small individual metal particles and hard foreign objects. No equivalence verification has been conducted against typical FOD caused by air rifle projectiles or sand particles.

Data availability

We have research data to declare. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sonar, T., Balasubramanian, V., Malarvizhi, S., Venkateswaran, T. & Sivakumar, D. An overview on welding of Inconel 718 alloy: Effect of welding processes on microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of joints. Mater. Charact. 174, 110997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2021.110997 (2021).

Uriati, F. & Nicoletto, G. A comparison of Inconel 718 obtained with three L-PBF production systems in terms of process parameters, as-built surface quality, and fatigue performance. Int. J. Fatigue 162, 107004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.107004 (2022).

Lee, D. et al. Correlation between microstructure and mechanical properties in additively manufactured Inconel 718 superalloys with low and high electron beam currents. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28, 2410–2419 (2023).

Ojo, N. L. & Richards, M. C. C. Study of the fusion zone and heat-affected zone microstructures in tungsten inert gas-welded INCONEL 738LC superalloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 37(2), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-006-0013-2 (2006).

García-Sesma, L., Álvarez, P., Gorostegui-Colinas, E., Huarte, I. & Santos, F. On alternatives to reduce hot cracking susceptibility of IN718 casting alloy laser beam welds with a mushroom shape. Metals 14(9), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14091067 (2024).

Wen, S. et al. Revealing the fatigue crack propagation mechanism of a Ni-based superalloy electron beam welded joint through in-situ SEM observation. Int. J. Fatigue 162, 106955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.106955 (2022).

Arcieri, E. V., Baragetti, S. & Božić, Ž. Stress assessment and fracture surface analysis in a foreign object damaged 7075–T6 specimen under rotating bending. Eng. Fail. Anal. 138, 106380 (2022).

Peters, J. & Ritchie, R. Influence of foreign-object damage on crack initiation and early crack growth during high-cycle fatigue of Ti–6Al–4V. Eng. Fract. Mech. 67(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-7944(00)00045-x (2000).

Spanrad, S. & Tong, J. Characterization of foreign object damage (FOD) and early fatigue crack growth in laser shock peened Ti-6AL-4V aerofoil specimens. Proced Eng. 2(1), 1751–1759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2010.03.188 (2010).

Zhu, L., Hu, X., Jiang, R., Song, Y. & Qu, S. Experimental investigation of small fatigue crack growth due to foreign object damage in titanium alloy TC4. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 739(214–22), 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2018.10.031 (2018).

Arcieri, E. V., Baragetti, S. & Božić, Ž. Limit load of notched Ti-6Al-4V specimens under axial fatigue. Procedia Struct Integr. 51, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostr.2023.10.059 (2023).

Lin, B., Lupton, C., Spanrad, S., Schofield, J. & Tong, J. Fatigue crack growth in laser-shock-peened Ti–6Al–4V aerofoil specimens due to foreign object damage. Int. J. Fatigue 59, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2013.10.001 (2013).

Fleury, R. et al. The effect of surface damage and residual stresses on the fatigue life of nickel superalloys at high temperature. Int. J. Fatigue 119, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2018.09.024 (2018).

Jia, X. et al. Foreign object damage characteristics and their effects on high cycle fatigue property of Ni-based superalloy GH4169. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 45(4), 1165–1178. https://doi.org/10.1111/ffe.13656 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Inconel 718 superalloy thin wall fabricated by pulsed plasma arc additive manufacturing. J. Alloys Compd. 819, 152936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152936 (2019).

Ghaemifar, S. & Mirzadeh, H. Precipitation kinetics of gamma double prime phase during direct aging treatment of Inconel 718 superalloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27, 4248–4255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.10.267 (2023).

Ramirez, A. & Lippold, J. High temperature behavior of Ni-base weld metal Part II: Insight into the mechanism for ductility dip cracking. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 380(1–2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2004.03.075 (2004).

Al-Lami, J., Dessolier, T., Rogers, S. R. & Pirzada, T. M. Pham, Dislocation distribution, crystallographic texture evolution, and plastic inhomogeneity of Inconel 718 fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Adv. Eng. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.202400524 (2024).

Piao, Y. & Le, K. C. Dislocation impediment by the grain boundaries in polycrystals. Acta Mech. 232(8), 3193–3213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-021-03007-3 (2021).

La Monaca, A., Axinte, D., Liao, Z., Neate, N. & Hardy, M. Interaction and competition between continuous and geometric dynamic recrystallization in high-strain-rate deformation of nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater 297, 121377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2025.121377 (2025).

Carl, E., Danilewsky, A., Meissner, E. & Geiger, T. Large- and small-angle grain boundaries in multi-crystalline silicon and implications for the evolution of grain boundaries during crystal growth. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 47(6), 1958–1965. https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576714023061 (2014).

Wang, J., Li, N. & Misra, A. Structure and stability of Σ3 grain boundaries in face centered cubic metals. Philos. Mag. 93(4), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2012.716908 (2012).

Liu, G., Winwood, S., Rhodes, K. & Birosca, S. The effects of grain size, dendritic structure and crystallographic orientation on fatigue crack propagation in IN713C nickel-based superalloy. Int. J. Plast. 125, 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijplas.2019.09.010 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. Microstructure and fatigue crack growth behavior of Inconel 718 superalloy manufactured by laser directed energy deposition. Int. J. Fatigue. 143, 106005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.106005 (2020).

Nowell, D., Duó, P. & Stewart, I. Prediction of fatigue performance in gas turbine blades after foreign object damage. Int. J. Fatigue 25(9–11), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0142-1123(03)00160-9 (2003).

Theska, F. et al. On the mechanisms controlling grain boundary cracking in Ni-based superalloy René 41 with boron and carbon additions. Mater. Des. 256, 114283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2025.114283 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Special Project for Transportation Equipment and Intelligent Transportation Technology, Grant No. 2023YFB4302400) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Special Fund No. 3122022PY18).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Special Project for Transportation Equipment and Intelligent Transportation Technology, Grant No. 2023YFB4302400) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Special Fund No. 3122022PY18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Jia: Writing – review and editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. Chen Han: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Qun Li: Data curation, Validation. Zhiping Wang.: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The pictures and tables involved in the paper are original and there are no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, P., Han, C., Li, Q. et al. Effect of foreign object damage on fatigue performance of Inconel 718 welded joints. Sci Rep 15, 44202 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27960-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27960-4