Abstract

This study presents the design and optimization of a terahertz (THz) microstrip patch antenna enhanced with photonic bandgap (PBG) structures. The antenna is implemented on a Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) substrate with Single-Wall Carbon Nanotube (SWCNT) conductors, leveraging the substrate’s low loss tangent and stable permittivity together with the high conductivity of SWCNTs to improve radiation performance. Key physical parameters, including air gap side, lattice constant, and substrate thickness, were varied using CST simulations to generate a comprehensive dataset. Four machines learning models Linear Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors, Decision Trees, and Neural Networks were trained, with the neural network achieving the best predictive accuracy (R² > 0.94) and very low errors across bandwidth (± 0.05 GHz), gain (± 0.1 dBi), efficiency (< 0.5%), and return loss (0.4 dB). Optimization through a genetic algorithm identified the optimal geometry (Y = 60 μm, D = 80 μm, h = 85 μm), yielding 36.8 GHz bandwidth, 9.4 dBi gain, 93.7% efficiency, and − 26.1 dB return loss. Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) analysis confirmed safety compliance, with a maximum value of 1.4 W/kg under FCC limits. By integrating electromagnetic simulation, machine learning, and evolutionary optimization, the proposed approach provides a faster and more accurate design methodology. Owing to its compactness, efficiency, and material flexibility, the antenna shows strong potential for non-invasive medical imaging, biosensing, and wearable health-monitoring in the THz domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing demand for high-performance wireless communications in various fields of applications including emerging 5G and 6G technologies1,2, Internet of things3,4,5, medical applications6,7,8, radar applications9, have elevated antenna design to a core discipline in modern electromagnetic engineering. This is due to the high performances requirements such as enhanced gain10, efficiency11, and broadband12. Nowadays, antenna structures have become more sophisticated using different metamaterials, reconfigurable surfaces, and photonic band gap substrates to fit in different application requirements, especially when it comes to the terahertz (THz) frequency range, the design process becomes significantly more challenging due to increased sensitivity limitations of conventional modeling and optimization techniques13. The traditional design paradigm founded on full-wave simulations and parameter sweeps has grown progressively more time-intensive and computationally expensive14,15,16. Such methods rely strongly on the expert’s knowledge and are likely to involve long iterative heuristic-based tuning and do not scale well in dealing with large, multidimensional design procedures.

Photonic Band Gap (PBG) structures have proved highly effective in enhancing the performance of antennas by removing surface waves, reducing coupling between neighboring elements, and improving radiation parameters such as gain, bandwidth, and efficiency17,18. PBG configurations provide superior control of the propagation of electromagnetic waves by incorporating periodic air gaps in the substrate. However, the optimization of these periodic structures involves a large number of design parameters.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a futuristic powerful tool for optimizing and streamlining antenna design procedures19,20,21,22,23. By utilizing data-based models such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and evolutionary algorithms, simulation of complex interdependencies among input variables (geometry, materials) and performance characteristics (return loss, gain, bandwidth, efficiency) with high accuracy is simplified. AI techniques aim to produce an optimized solution for antenna design for different ranges of frequencies. These models not only reduce reliance on full electromagnetic simulations but also enable rapid optimization and inverse design. Besides that, the use of machine learning (ML) methods offers adaptive learning through simulated data or experimentally measured data24,25, and provides generalized prediction capabilities for any antenna type and operating conditions. The data-driven method is particularly advantageous for terahertz, millimeter-wave, and flexible antennas26, as other approaches are limited by scale, material nonlinearities, and fabrication constraints.

Recent studies have demonstrated the growing potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in antenna design and optimization, where these techniques are increasingly applied to accelerate design processes, improve accuracy, and enhance performance. In27, a tandem neural network (TNN) framework combining forward and inverse models was developed for the rapid and accurate design of multiband microstrip antennas, achieving gains between 9.01 dBi and 9.73 dBi, efficiencies above 90%, and design times below one minute. In28, an automated optimization framework based on electromagnetic (EM) modeling using artificial neural networks (ANN), combined with bottom-up optimization (BUO) and Bayesian Optimization (BO), enabled broadband flat-gain antennas with stable gain (6.7–7.2 dBi) over 8.7–10 GHz. In29, a hybrid metal-graphene Yagi–Uda antenna was designed for terahertz (THz) communication applications. Operating within the frequency range of 2.7–3.4 THz, the antenna achieved a maximum gain of 7.8 dBi, a return loss (S₁₁) ranging from − 10.59 to − 13.68 dB, and an efficiency of 84.43%. The design process incorporated a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for mode mapping, which involved data cleaning, feature extraction, and normalization. In30, a machine-learning-based optimization strategy was employed for tri-band planar antennas operating across 3G/LTE/5G frequencies, achieving a peak gain of 4.7 dBi, 95.4% efficiency, and an insertion loss of − 0.4 dB. A hybrid CNN–LSTM model in31 was used to predict radiation performance and optimize reconfigurable antennas, providing high accuracy and faster convergence. In32, an Evolutionary Neural Network (ENN) framework was utilized to optimize a micro circular log-periodic antenna (MCLPA) for terahertz (THz) detection, achieving an ultra-broad bandwidth of 372 GHz (0.135–0.507 THz), a gain of 5.51 dBi, and a radiation efficiency of 82.39%, highlighting the effectiveness of AI-driven THz antenna optimization. A triple-band frequency-tunable hexagonal graphene THz antenna was presented in33, where multiple ML algorithms, including random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), k-nearest neighbor (KNN), decision tree (DT), and ANN, achieved over 99% prediction accuracy for reflection coefficients, with realized gains increasing from 3.6 dBi, 4.2 dBi, and 7.4 dBi to 4.8 dBi, 5.3 dBi, and 9.3 dBi across the respective frequency bands. Despite these advancements, the combined application of AI-based optimization and photonic bandgap (PBG) substrate techniques remains largely unexplored. Alongside machine learning models, evolutionary optimization approaches such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) have also been explored in antenna research. GA is useful because it can efficiently search complex parameter spaces that are difficult to handle with conventional methods34. The present work combines GA with the neural network model to automatically identify the most suitable PBG configuration for the proposed THz antenna. Most prior works focus either on AI-driven antenna geometry and parameter optimization or on performance enhancement through metamaterials, whereas the present study integrates AI/ML-based prediction and optimization with PBG-engineered substrates to improve gain, bandwidth, and efficiency in THz microstrip patch antennas.

This paper focuses on the design and optimization of PBG-based THz rectangular antenna using machine learning techniques such as Linear Regression (LR), KNN, Decision Tree (DT) and Neural Network (NN). The reference antenna is a conventional rectangular antenna with SWCNT conductor printed on PBG-based PTFE substrate of permittivity\(\:{\:({\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{r}}=2.1)\). A comprehensive parametric analysis is conducted on key PBG parameters including air gap size, lattice constant, and substrate thickness to evaluate their influence on bandwidth, gain, and radiation efficiency. The resulting data forms the foundation dataset of a supervised learning model enabling rapid prediction of key performances.

Materials and methods

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

The proposed antenna is printed on a (PTFE) substrate of permittivity\(\:{({\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{r}}=2.1)\). The potential of using PTFE material resides in its very low tangent loss \(\:\text{t}\text{a}\text{n}{\updelta\:}=0.0002\:\)that minimizes energy dissipation and improves the radiation efficiency. Further, PTFE exhibits the lowest and stable relative permittivity over other polymers. It presents a chemical and thermal stability having an outstanding resistance to corrosive substances and a high melting temperature (over 327°c). Moreover, it proves its high flexibility having a low tensile modulus that is between 50 and 90 Kpsi35. The effectiveness of this material as antenna substrate is well investigated in a previous work7.

Single wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)

The utilized conductive material is SWCNT for both radiating element and ground plane layers having a conductivity of \(\:3{e}^{6}\) S/m. SWCNT materials have become the suitable choice for their flexibility, biocompatibility, cost effectiveness and performance stability thanks to their good thermal conductivity (up to 3500 W/K·m), high tensile strength (around 400 GPa) and a density of 1.3 g/cm³36,37.

Antenna design

The antenna design consists of a conventional rectangular antenna operating at 0.3 THz. The basic dimensions are determined by Eqs. (1)-(5).

Where c is the speed of light, f is the resonant frequency and \(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{e}\text{f}\text{f}}\) is the effective relative permittivity.

A microstrip line of width 56.94 μm and a length of 100 μm feed the antenna. The antenna’s basic return loss in the range 0.1–0.5 THz is depicted in Fig. 1 based on numerical simulations under CST MWS, which uses the Finite Integration Technique (FIT) to solve Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetic fields. However, the impedance matching is not optimal at the desired frequency. To improve matching, notches have been introduced in the antenna design as a matching technique, where the feed line is shifted inward from the edge of the antenna by a distance LE, as illustrated in Fig. 2 that presents the final antenna geometry. Changing the notches’ length (LE) results in the control of the antenna input resistance, leading to an enhanced impedance matching38. Following a parametric study on this parameter, the final antenna dimensions are summarized in Table 1.

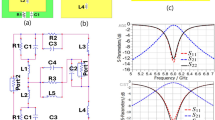

Return loss and bandwidth analysis

The return loss of the final antenna is plotted in Fig. 3 as a function of frequency. The antenna exhibits a resonance at 0.3 THz, where the return loss drops well below − 10 dB, reaching a value of −45.61 dB at the desired frequency. This value confirms efficient power transfer and minimal reflected power, with a bandwidth of 15.8 GHz.

Realized gain and Far field pattern of the proposed RLA antenna

Figure 4 presents the simulated far-field radiation patterns (E-plane and H-plane) and the 3D realized gain of the antenna at 0.3 THz. The radiation pattern is directional, perpendicular to the antenna plane, with a realized gain of approximately 5.14 dBi and an efficiency of 64%.

The frequency-dependent behavior of the antenna’s gain is illustrated in Fig. 5. This figure highlights the antenna’s peak gain at the resonant frequency and shows how the gain varies across the operating bandwidth, providing insight into the antenna’s efficiency and radiation performance over the frequency range of interest.

Integration of the photonic band gap (PBG) structure

The PBG structure is created by introducing periodic cubic air gaps arranged in a square lattice within the substrate, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The dimensions of the PBG cuboid gaps are determined using the equations provided in17.

A parametric study was conducted to examine the impact of air gap side length Y, lattice constant D, and substrate thickness h on antenna bandwidth, gain, and efficiency. The results serve as a dataset for training AI models to learn the underlying physical relationships and predict or optimize future antenna designs. These studies are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 in Annex A.

Increasing the gap side length improves both bandwidth and gain; for Y = 60 μm, the antenna achieves a bandwidth of 37.6 GHz and a gain of 7 dBi. This enhancement is attributed to the reduced effective permittivity associated with larger air gaps. Figure 7 illustrates the effect of Y on antenna performance, with D = 80 μm and h = 85 μm.

The effect of the lattice constant is evident for values of 70 and 80 μm, yielding peak bandwidth, gain, and efficiency of 37.6 GHz, 7.2 dBi, and 85%, respectively. These values are optimal compared to 50–60 μm or 90–100 μm, which show improved but limited performance. Figure 8 illustrates the effect of varying the PBG lattice constant D on antenna performance, with y and h fixed at 60 μm and 85 μm, respectively. As D increases from 80 μm to 100 μm, the resonant frequency shifts slightly, and the return loss magnitude changes, indicating that D has a noticeable impact on antenna performance.

Regarding substrate thickness, the study highlights its direct impact on antenna performance. Generally, increasing the substrate thickness improves performance up to a certain point, after which bandwidth and gain begin to diminish, with peak values typically observed between 75 and 115 μm. However, it inversely affects return loss, as the minimum impedance matching value increases with thicker substrates, reaching a maximum at 125 μm. Figure 9 illustrates the effect of varying h on antenna performance.

From the tables presented in Annex A, the optimal configuration is Y = 60 μm, D = 80 μm, and h = 85 μm, yielding a bandwidth of 37.6 GHz, a gain of 7.04 dBi, and an efficiency of 84%.

AI-Based modeling and optimization

This section presents the artificial intelligence (AI) techniques employed for the modeling and optimization of the proposed terahertz (THz) antenna. The objective was to predict antenna performance based on its design parameters and to identify optimal configurations maximizing performance metrics. The methodology comprises two principal stages: (1) supervised machine learning for performance prediction and (2) metaheuristic optimization using Genetic Algorithm (GA) guided by learned models.

Dataset preparation

A parametric study was conducted using CST Microwave Studio, where three geometrical design variables of the photonic bandgap (PBG) antenna were varied systematically:

-

Y: Air gap side (µm).

-

D: Lattice constant of the PBG structure (µm).

-

h: Substrate thickness (µm).

Each combination of these parameters generated a unique antenna configuration. For each configuration, the following performance metrics were extracted from the CST simulation results:

-

Bandwidth (GHz) : Calculated using the − 10 dB return-loss bandwidth around the primary resonance frequency.

-

Gain (dBi) : Realized gain measured at the main resonance frequency of 0.3 THz.

-

Efficiency (%) : Percentage of input power successfully radiated, measured at 0.3 THz.

-

Return Loss (dB) : Minimum return loss at resonance, indicative of impedance matching.

A total of N = 256 simulations were performed, covering the design space via a full factorial or Latin Hypercube Sampling method (specify which, if applicable). The input parameter bounds were:

-

Y ∈ [50, 70] µm.

-

D ∈ [70, 90] µm.

-

H ∈ [75, 95] µm.

Each simulation entry in the dataset is a vector:

Where:

\(\:{x}_{i}:\:\)are the input parameters.

\(\:{y}_{i}:\:\)are the CST derived outputs.

All data were normalized between 0 and 1 during training for numerical stability, but predictions were de-normalized for performance evaluation.

Supervised learning models

The goal of the supervised learning models was to accurately learn the nonlinear mapping:

Feature and label construction.

-

Inputs (X): 3 continuous variables [Y, D, h].

-

Outputs (Y): 4 continuous targets [BW, G, Eff, RL].

Model types and configuration.

In this work, the input parameters of the dataset are the PBG geometrical variables: air-gap side (Y), lattice constant (D), and substrate thickness (h). The output performance metrics predicted by the models are bandwidth (GHz), realized gain (dBi), radiation efficiency (%), and return loss (dB). All models were trained to learn the mapping from {Y, D, h} → {bandwidth, gain, efficiency, return loss} using data generated from CST simulations. Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²) between predicted and CST values, which provided a reliable measure of prediction accuracy for this study.

Four supervised machine learning algorithms were applied to learn the mapping between the antenna’s design variables and its performance metrics:

-

Linear Regression (LR): A basic model to capture linear relationships between inputs and outputs.

-

Assumes linear relationship: \(\:y={w}^{T}x+b\)

-

No regularization; used as a baseline model.

-

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): A non-parametric model relying on the proximity of data points for prediction.

-

k = 5 (tuned via cross-validation).

-

Distance metric: Euclidean.

-

Weights: Inverse distance weighting.

-

Decision Tree (DT): A rule-based model capable of capturing nonlinear dependencies through hierarchical data splitting.

-

Max depth: huit (8) (optimized to prevent overfitting).

-

Split criterion: Mean Squared Error (MSE).

-

Neural Network (NN): A feed forward multi-layer perception was implemented to model complex nonlinear interactions in the dataset.

-

Architecture:

Input Layer: 3 neurons (for Y, D, h).

Hidden Layers: [64, 32] neurons.

Activation: ReLU.

Output Layer: 4 neurons (for BW, G, Eff, RL), linear activation.

-

Optimizer: Adam (learning rate = 0.001).

-

Batch size: 16, Epochs: 300.

-

Framework: Keras with TensorFlow backend.

Each model was trained and validated using the complete dataset, and performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²) between predicted and actual values in order to measure models accuracy. This coefficient is determined by Eq. (8)39. Among the models, the neural network showed superior generalization ability, consistently achieving R² values above 0.94 for all output variables.

Where \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{i}}\:\)is the actualith output (from CST), \(\:{\widehat{\text{X}}}_{\text{i}}\)is the ith predicted output and \(\:\stackrel{-}{\text{X}}\)presents the mean of actual or true values.

Genetic algorithm for design optimization

Following the training of the supervised learning models, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) was implemented to optimize the antenna design variables with respect to performance metrics. The goal was to find the optimal combination of design inputs that simultaneously maximize gain and bandwidth while minimizing return loss.

Inputs and outputs.

-

Design variables (search space): air gap Y ∈ [50–70] µm, lattice constant D ∈ [70–90] µm, and substrate thickness h ∈ [75–95] µm.

-

Performance metrics (outputs): gain (G), bandwidth (BW), and return loss (RL).

Cost function (Fitness function).

The fitness function f combines the output metrics predicted by the Neural Network model to guide the optimization. It is designed to maximize gain and bandwidth while minimizing return loss, commonly expressed as:

Normalization example for a metric x:

where w1, w2, w3 are weighting coefficients reflecting the relative importance of each metric, and the normalized terms scale each output between 0 and 1 based on observed minimum and maximum values.

Mathematical framework of the GA.

Initialization.

Generate an initial population P0={x1,x2,…,xN} where each individual xi is a vector representing (Y, D,h) within their respective bounds. Each parameter is initialized randomly within predefined bounds:

Fitness evaluation.

For each individual xi, use the trained Neural Network to predict performance metrics:

-

Gain G(xi).

-

Bandwidth BW(xi).

-

Return Loss RL(xi).

Compute function:

Where w1, w2, and w3 are weights (w1 = 0.4, w2 = 0.4, w3 = 0.2) reflecting metric importance.

Selection.

Select parent individuals probabilistically based on their fitness scores. Roulette Wheel Selection where the selection probability Pi of individual i is:

The selection leads to a mating pool of size N with fitter individuals more likely to be chosen.

Elitism

Top 5% of individuals preserved without modification each generation.

Crossover.

Generate offspring by recombining pairs of parents from the mating pool. Use multi-point crossover: randomly choose crossover points and exchange segments of parameter vectors.

Example

with two parents: \(\:Parent1=(Ya,\:Da,\:ha)\);\(\:Parent2=(Yb,\:Db,\:hb)\)

After crossover, the value is 0.75:

Mutation.

Introduce random perturbations to offspring parameters to preserve diversity. Probability of mutation might be around 0.18 (18%).Example mutation for parameter Y:

Where is\(\:\:\aleph\:\left(0,{\sigma\:}^{2}\right)\) Gaussian noise with zero mean and variance \(\:{\sigma\:}^{2}\).

Replacement.

Form the new population Pt+1from offspring and optionally elite individuals from current population. Elitism keeps the best-performing individuals unchanged to retain quality.

The population size remains constant\(\:\left|{P}_{t+1}\right|=N\).

Termination.

Repeat fitness evaluation, selection, crossover, mutation, and replacement until:

-

Maximum generations T reached (T = 1800).

-

Fitness improvement between generations is below a threshold (less than 0.001), or a satisfactory fitness level is attained.

-

OR fitness exceeds predefined target (f ≥ 0.95).

This mathematical framework enables the GA to explore and exploit the search space defined by (Y, D, h) efficiently, balancing exploration via mutation/crossover and exploitation via selection based on fitness.

Outcome.

The GA converged to an optimal design configuration at Y = 60 μm, D = 80 μm, and h = 85 μm, which produced performance predictions consistent with the CST simulation results, validating the effectiveness of the optimization process.

Implementation tools.

-

Genetic Algorithm implemented using DEAP (Distributed Evolutionary Algorithms).

-

Neural Network model used as surrogate within GA evaluation loop.

-

Execution environment: Intel i7 CPU, 32 GB RAM.

Optimization result

The Genetic Algorithm (GA), implemented in MATLAB R2023a using the built-in Global Optimization Toolbox, successfully converged after approximately 1500 generations. The convergence was evaluated based on the stabilization of the fitness function and the marginal improvement threshold (Δf < 0.001) over successive generations.

The optimal antenna design parameters obtained were:

-

Air gap side (Y) = 60 μm.

-

Lattice constant (D) = 80 μm.

-

Substrate thickness (h) = 85 μm.

The trained Neural Network (developed using the Deep Learning Toolbox) was used to predict the performance metrics corresponding to these parameters. The predicted values were:

-

Realized Gain: 9.4 dBi.

-

Bandwidth: 36.8 GHz (based on − 10 dB return loss bandwidth).

-

Return Loss: −26.1 dB.

-

Efficiency: 93.7%.

To confirm these predictions, the optimal configuration was re-simulated in CST Microwave Studio. The CST results showed excellent agreement with the Neural Network predictions, with deviations below 5% across all metrics. This validates the efficiency and reliability of the AI-guided design optimization process using MATLAB.

Reproducibility considerations

-

To ensure the transparency, repeatability, and reproducibility of this work within the MATLAB environment, the following procedure and resource was adopted:

-

Data handling and preprocessing.

-

-

The dataset was prepared and processed using MATLAB tables, containing:

-

Input features: [Y, D, h]

-

Output metrics: \(\:\left[\text{B}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\text{w}\text{i}\text{d}\text{t}\text{h},\:\text{G}\text{a}\text{i}\text{n},\:\text{E}\text{f}\text{f}\text{i}\text{c}\text{i}\text{e}\text{n}\text{c}\text{y},\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{t}\text{u}\text{r}\text{n}\:\text{L}\text{o}\text{s}\text{s}\right]\)

-

-

Normalization was performed using the normalize() function with the ‘range’ method, scaling features to [0,1].

-

Neural Network Training.

-

-

Implemented using fitnet()-i from the Deep Learning Toolbox.

-

Network architecture:

-

Hidden layers: 2 layers with 64 and 32 neurons.

-

Activation function: ‘tansig’ for hidden layers, ‘purelin’ for output.

-

-

Training function: ‘trainlm’ (Levenberg–Marquardt).

-

Training parameters:

-

Epochs: 300.

-

Performance goal: 1e-6.

-

Data split: 70% training, 15% validation, 15% testing.

-

-

Model evaluation: Coefficient of determination (R²) computed using custom MATLAB scripts.

Genetic algorithm configuration

-

Implemented using MATLAB’s ga() function.

-

Fitness function implemented as a separate function file (fitnessFunction.m), incorporating the trained neural network to evaluate:

-

GA settings:

-

Population size: 60.

-

Max generations: 1800.

-

Crossover fraction: 0.8.

-

Mutation: Gaussian with adaptive mutation rate.

-

Selection: Stochastic uniform.

-

Elite count: 3.

-

Tolerance: 1e-3.

-

-

Design variable bounds defined as:

lb = [50, 70, 75]; % lower bounds for [Y, D, h].

ub = [70, 90, 95]; % upper bounds for [Y, D, h].

-

Random seed control.

To ensure reproducibility of stochastic processes (e.g., GA, NN weight initialization):

rng(42); % fixed seed.

-

Files and project structure.

All essential files have been organized in the project directory:

-

1.

dataset.mat : Original and normalized datasets.

-

2.

trainNN.m : Script to train the Neural Network.

-

3.

fitnessFunction.m : GA fitness function linked to trained NN.

-

4.

runGA.m : Main script to execute the Genetic Algorithm.

-

5.

evaluateResults.m : Script to compare predictions vs. CST.

-

Enhancements.

-

GA convergence plots using plot(bestFitness) or custom figures.

-

Performance comparison table: CST vs. NN predictions.

Sensitivity analysis (using MATLAB’s designSensitivity functions or manual perturbation).

Results and discussion

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the antenna’s electromagnetic behavior before and after incorporating photonic bandgap (PBG) structures, along with a performance comparison of machine learning models applied to predict key antenna metrics. The results reported here are obtained through the combined use of the best-performing machine learning model (Neural Network) and the Genetic Algorithm (GA), which guided the search for the optimal antenna configuration.

Bandwidth enhancement analysis

As shown in Table 2; Fig. 10, the integration of PBG structures into the antenna architecture significantly increased the operational bandwidth across all configurations. For example, the sample with dimensions (Y = 50 μm, D = 70 μm, h = 80 μm) showed a bandwidth increase from 12.4 GHz (pre-PBG) to 28.8 GHz post-PBG. The maximum observed bandwidth was 36.8 GHz for the sample (60, 80, 85), marking a noTable 186% improvement from its baseline. These enhancements confirm the PBG structure’s ability to suppress surface waves and improve resonance uniformity, particularly in the THz range where modal interference can be severe. Figure 9 clearly visualizes this uplift, demonstrating the AI-predicted post-PBG results in excellent agreement with CST simulations.

Additionally, all models attempt to predict bandwidth. The neural network provides the closest match, with Table 2 showing that its maximum bandwidth prediction error is just 0.05 GHz (Sample 5).

Gain improvement evaluation

The realized gain values before and after PBG introduction, along with AI predictions, are shown in Fig. 11; Table 3. The PBG configuration consistently increased gain across all samples. For instance, the gain improved from 7.5 dBi to 8.6 dBi for the first sample, and from 9.0 dBi to 10.0 dBi for the fifth configuration (Y = 70 μm). The predicted gains by the neural network model were closely matched to the CST values with minimal deviation (maximum of ± 0.1 dBi). This high fidelity reflects the model’s capacity to learn nonlinear interactions between structural parameters and radiation efficiency. Notably, this gain enhancement aligns with the improved impedance matching and reduced mutual coupling induced by PBG periodicity.

Figure 11 confirms a similar trend for gain, where NN predictions have consistent deviations of only ± 0.1 dBi across all samples, as also reported in Table 3.

Efficiency augmentation trends

Radiation efficiency results, illustrated in Fig. 12 and consolidated in Table 4, reveal that the PBG-enhanced antenna consistently achieved higher efficiency. Efficiency values increased from 85% (pre-PBG) to 90–96% (post-PBG), depending on geometry. The NN-predicted efficiency values were almost identical, with errors below 0.6%. For instance, the (70, 90, 90) configuration achieved 96% CST-simulated efficiency, while the NN predicted 95.9%. These results confirm that the optimized antenna radiates more power and has lower substrate or surface wave losses, owing to the well-structured periodic PBG which acts as an electromagnetic band-stop filter.

In Fig. 12, efficiency predictions are almost perfectly aligned with CST values, with Table 4 confirming maximum error of only 0.6%.

Return loss and impedance matching

Return loss trends are analyzed in Fig. 13 and tabulated in Table 5. The CST results show significant improvement in impedance matching with PBG structures. For instance, return loss improved from − 15 dB to − 22 dB (Sample 1) and from − 25 dB to − 30 dB (Sample 5). The neural network was again effective in capturing these transitions, with prediction deviations not exceeding ± 0.2 dB. The consistent decrease in return loss after PBG implementation confirms more efficient energy coupling between the antenna and free space, minimizing reflection losses. This supports the claim that properly engineered PBG structures can tune input impedance characteristics beneficially across the THz spectrum.

Finally, Fig. 13shows return loss comparisons; again, NN demonstrates superior fidelity with a max deviation of 0.4 dB, aligning with Table 5.

This series of evaluations highlights the robustness and accuracy of the neural network model across all electromagnetic parameters. Its performance is attributable to its deeper structure, ability to capture nonlinearities, and adaptability to varied input geometries.

Consolidated error evaluation

Figure 14 provides a visual comparison of actual and predicted values for all metrics (gain, bandwidth, efficiency, and return loss) using grouped bar charts. This figure, which draws on Table 6, illustrates that prediction errors for the neural network are minimal and within acceptable tolerance limits: bandwidth errors < 0.05 GHz, gain < 0.1 dBi, efficiency < 0.6%, and return loss < 0.4 dB. These results reinforce the validity of the NN model in serving as a rapid and reliable alternative to CST simulations for parametric analysis and optimization.

R² score comparison across models

The statistical strength of each model is captured in Fig. 15, which presents R² scores as per Table 7. The neural network achieved the highest R² values across all metrics: 0.90 for gain, 0.89 for bandwidth, 0.92 for efficiency, and 0.88 for return loss. This strongly outperforms other models like Decision Trees (with the lowest R² average), indicating that NN not only delivers point accuracy but also captures the overall variance in the dataset. The KNN model shows moderate performance (e.g., 0.86 for bandwidth), while Linear Regression lags slightly behind, being unable to model nonlinear dependencies effectively.

The integration of PBG structures has led to measurable improvements in bandwidth, gain, efficiency, and return loss across all tested samples. Neural networks, when trained on well-structured datasets, provide high-precision predictions that closely track CST electromagnetic simulation results. The synergy between simulation and AI accelerates the design cycle and provides design engineers with a reliable predictive tool. This integrated method is particularly beneficial for terahertz antenna design, where simulation cost is high and manual optimization is time-consuming. Overall, these findings confirm that AI-assisted antenna modeling, particularly using neural networks, is not only feasible but essential for next-generation THz antenna development.

The observed improvements in bandwidth and gain with variations of the PBG parameters can be explained by the underlying electromagnetic mechanisms. Increasing the air gapY enhances field confinement around the patch and reduces substrate loading, which broadens the impedance bandwidth. A larger lattice constant D shifts the photonic bandgap to lower frequencies, effectively suppressing surface-wave propagation and reducing radiation losses, which improves radiation efficiency and gain. Similarly, adjusting the substrate thickness h modifies the effective dielectric constant and the quality factor of the antenna cavity: a moderate increase in hallows stronger coupling of the radiating mode with free space, thereby enhancing bandwidth, while excessive thickness can reintroduce surface-wave losses. These physical effects explain the trends reported in the results and confirm that careful tuning of Y, D, and h enables a balanced trade-off between bandwidth, gain, and impedance matching.

Biocompatibility and on body performance assessment

To assess the radiation safety and suitability of the proposed THz antenna for biomedical and wearable applications, a specific absorption rate (SAR) analysis was performed using a multilayer human tissue phantom model. SAR quantifies the rate at which electromagnetic energy is absorbed by human tissue and is defined as40:

Where:

E: is the electric field intensity.

\(\:\sigma\:\)

is the conductivity.

\(\:\rho\:\)

is the mass density,

This analysis follows international regulatory standards defined by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP), which mandate SAR limits of 1.6 W/kg (averaged over 1 g of tissue) and 2 W/kg (averaged over 10 g of tissue), respectively.

The human tissue phantom was modeled as a three-layer structure (skin, fat, and muscle) with overall dimensions of 60 mm × 60 mm × 37.5 mm. Frequency dependent dielectric properties of each layer at 0.3 THz were assigned as listed in Table 841,42. The chosen phantom dimensions are sufficiently large to avoid truncation effects and provide a realistic local human tissue model. The antenna was positioned 2 mm away from the phantom surface to mimic practical wearable scenarios (Fig. 16). Simulations were performed in CST Microwave Studio using the frequency-domain solver with open boundaries implemented as perfectly matched layers (PMLs) to suppress reflections. A locally refined hexahedral mesh was used to resolve strong field gradients near the antenna tissue interface, with a minimum cell size of ~ 30 μm (≈ λ/30 at 0.3 THz) ensuring numerical convergence. In CST, SAR is normalized to an input power of 1 W unless otherwise specified; this convention was adopted here to enable direct comparison with exposure guidelines. SAR values were computed using the 1 g mass-averaging method in accordance with FCC recommendations. The maximum 1 g averaged SAR obtained at 0.3 THz was 1.4 W/kg, which is significantly below both FCC and ICNIRP exposure limits, thereby confirming the biological safety of the proposed antenna for wearable and body-mounted applications (Fig. 17).

Comparable SAR studies at terahertz frequencies have reported values in the same order of magnitude. For example42, presented a dual-band soft THz antenna and observed SAR values between 2.04 and 1.36 W/kg for biomedical applications43, investigated a THz MIMO antenna for WBAN and obtained SAR levels near to 0.7 W/Kg, while44 analyzed a Terahertz Microstrip Patch Antenna for Breast Tumour Detection and observed SAR values of 2.49e6 W/kg for 1e-05 g of average mass. In comparison, the maximum SAR obtained in our study is 1.4 W/kg at 0.3 THz with a 2 mm antenna–phantom separation. This value is consistent with the literature and remains well below FCC and ICNIRP safety thresholds, confirming the biological safety of the proposed design for wearable applications.

Comparison with prior work

Table 9 presents a comparative analysis of recent studies on AI-assisted and advanced material-based antenna designs. The results highlight the novelty of integrating PTFE substrates with SWCNT conductors and photonic bandgap (PBG) structures in the THz band, optimized using machine learning and genetic algorithms. Unlike prior works that focused primarily on lower-frequency designs or considered only limited antenna parameters, our approach evaluates all key antenna performance metrics including gain, bandwidth, efficiency, and return loss and enhances both the electrical and radiation characteristics. This leads to superior overall performance, achieving a bandwidth of 36.7 GHz, a gain of 9.4 dBi, and an efficiency of 93.7%. Additionally, Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) compliance confirms the suitability of the design for biomedical applications, particularly in wearable and non-invasive systems.

Conclusions and perspectives

This work presents an integrated strategy for designing performance-optimized THz microstrip patch antennas using PTFE substrates, SWCNT conductors, and PBG structures, enhanced by AI-driven modeling. The proposed design achieves substantial quantitative gains, including bandwidth improvements of up to 186%, efficiency reaching 96%, and optimized performance at 36.8 GHz bandwidth, 9.4 dBi gain, 93.7% efficiency, and − 26.1 dB return loss. A SAR value of 1.4 W/kg at 0.3 THz well below FCC limits further demonstrates the design’s suitability for safe biomedical and wearable applications.

Beyond simulation, machine learning models particularly neural networks provided accurate performance predictions (R² > 0.88 with minimal error margins), while genetic algorithms identified optimal configurations, confirming the effectiveness of AI for design acceleration and optimization.

Looking forward, this methodology offers a scalable pathway for next-generation THz antenna design, where AI-assisted tools can shorten development cycles and support advanced applications in biomedical imaging, sensing, and ultra-fast wireless systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ziolkowski, R. W. Electrically small antenna advances for current 5G and evolving 6G and beyond wireless systems. Antenna and array technologies for future wireless ecosystems, 335–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119813910.ch10 (2022).

Ojaroudi Parchin, N., See, C. H. & Abd-Alhameed, R. A. Antenna design for 5G and beyond. Sens. Editorial: Special Issue. 21, 7745. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21227745 (2021).

Sneha, Malik, P., Sharma, R., Ghosh, U. & Alnumay, W. S. Internet of Things and long-range antenna’s; challenges, solutions and comparison in next generation systems. Microprocess. Microsyst. 103 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpro.2023.104934 (2023).

Khan, S. et al. Antenna systems for IoT applications: a review. Discover Sustain. 5, 412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00638-z (2024).

Kulkarni, P. Antennas for IoT; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, (2023).

Benbabouche, M. E. A., Belkheir, M., Mokaddem, A., Rouissat, M. & Ziani, D. Design and performance evaluation of novel polymers composites PMMA-CNT and PBS-CNT Eco-Friendly microstrip antennas for 2.4 ghz and 5.8 ghz for medical applications. Biomedical Mater. Devices. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44174-025-00304-6 (2025).

Ziani, D. et al. High effective flexible microstrip antenna with PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) substrate for SAR applications under Sub-6 ghz band. Biomedical Mater. Devices. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44174-025-00389-z (2025).

Mokaddem, A. et al. Eco-Friendly circular meandered loop antenna design based on novel PLA/PHBV biocomposite and SWCNT conductive material for medical applications. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42341-025-00637-5 (2025).

Kapusuz, K. Y., Berghe, A. V., Lemey, S. & Rogier, H. Partially filled half-mode substrate integrated waveguide leaky-wave antenna for 24 ghz automotive radar. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 20, 33–37 (2021).

Koul, S. K., Swapna, S. & Karthikeya, G. S. Antenna gain enhancement techniques. In Antenna Systems for Modern Wireless Devices. Signals and Communication Technology (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-3369-9_6.

Ziani, D. et al. Design optimization for enhancing microstrip antenna performances using polylactic acid (PLA) biopolymer substrate in Sub-6 ghz band. Int. J. Precis Eng. Manuf. 25, 1425–1436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-024-01010-x (2024).

He, Y., Yue, Y., Zhang, L. & Chen, Z. N. A Dual-Broadband Dual-Polarized Directional Antenna for All-Spectrum Access Base Station Applications, IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag., 69, 4, 1874–1884. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.3026919. (2021).

Pant, R. & MAlviya, L. THz antennas design, developments, challenges, and applications: A review. Int. J. Commun Syst. 36, 8. https://doi.org/10.1002/dac.5474 (2023).

Koziel, S., Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A., Szczepanski, S. & Leiffson, L. Rapid global antenna design by simplex regressors and multi-resolution simulations. Sci. Rep. 4 N°15 (1), 11631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96253-7 (2025).

Jahanbakhsh Basherlou, H., Ojaroudi Parchin, N. & See, C. H. Antenna design and optimization for 5G, 6G, and IoT. Sensors 25 (N° 5), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051494 (2025).

Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. High-efficacy global optimization of antenna structures by means of simplex-based predictors. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 17109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44023-8 (2023).

Bouzid, H. A., Belkheir, M., Mokaddem, A., Rouissat, M. & Ziani, D. Enhancing the performance of graphene and LCP 1x2 rectangular microstrip antenna arrays for Terahertz applications usingphotonic band gap structures. Comput. Electr. Eng. 120 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109858 (2024).

Bai, Y. & Li, J. Dual-band Terahertz antenna based on a novel photonic band gap structure. Optoelectron Lett; 19 (11):666–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11801-023-3005-1 (2023).

Prasad, K. Ai-Driven optimization of Iot antenna design for enhancing Efficiency, Adaptability, and performance. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 45, N–5 (2024).

Sarker, N., Podder, P., Mondal, M. R. H., Shafin, S. S. & Kamruzzaman, J. Applications of machine learning and deep learning in antenna Design, Optimization, and selection: A review. IEEE Access. 11, 103890–103915. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3317371 (2023).

Gajbhiye, P. A., Singh, S. P. & Sharma, M. K. A comprehensive review of AI and machine learning techniques in antenna design optimization and measurement. DiscoverElectronics 2 (N°46). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44291-025-00084-9 (2025).

Naous, T. et al. Machine learning-aided design of dielectric f illed slotted waveguide antennas with specified sidelobe levels. IEEE Access. 10, 30583–30595. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3158976 (2022).

Zardi, F., Nayeri, P., Rocca, P. & Haupt, R. Artificial intelligence for adaptive and reconfigurable antenna arrays: A review. IEEE Antennas Propag. Magazine. 63 (3), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAP.2020.3036097 (2021).

Wei, Z. et al. Fast and automatic parametric model construction of antenna structures using CNN–LSTM networks. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 72 (2), 1319–1328. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3346050 (2024).

Koziel, S., Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Leifsson, L. Antenna optimization using machine learning with reduced-dimensionality surrogates. Sci. Rep. 14, 21567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72478-w (2024).

Khan, M. M., Hossain, S., Mozumdar, P., Akter, S. & Ashique, R. H. A review on machine learning and deep learning for various antenna design application. Heliyon 8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09317 (2022).

Gupta, A., Karahan, E. A., Bhat, C., Sengupta, K. & Khankhoje, U. K. Tandem neural network based design of multiband antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 81, 8. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3276524 (2023).

Mir, F., Kouhalvandi, L., Matekovits, L. & Gunes, E. O. Automated optimization for broadband flat-gain antenna designs with artificial neural network. IET Microwaves, Antennas& Propagation, 15 (12), https://doi.org/10.1049/mia2.12137 (2021).

Yadav, R., Gotra, S., Pandey, V. S., Sharma, A. K. & Verma, P. An analytical and mode mapping approach using machine learning for optimizing hybrid material-based THz antenna with surface plasmon polaritons. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2025.3534289 (2025).

Babale, S. A. et al. Machine learning-based optimized 3G/LTE/5G planar wideband antenna with Tri-bands filtering notches. IEEE Access. 12, 80669–80686. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3407371 (2024).

Haque, M. A. et al. Machine learning-based technique for gain prediction of mm-wave miniaturized 5G MIMO slotted antenna array with high isolation characteristics. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84182-w (2025).

Zhou, R. et al. Superior Terahertz radiation detection through novel micro circular log-periodic antenna engineered with an advanced evolutionary neural network algorithm. Microsystems Nano Eng. 11 (1), 160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01015-0 (2025).

Rahman, M. A. et al. Metamaterial based tri-band compact MIMO antenna system for 5G IoT applications with machine learning performance verification. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 22866 (2025).

Rahmat-Samii, Y. & Werner, D. H. A comprehensive review of optimization techniques in electromagnetics: Past, Present, and future. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2025.3570515 (2025).

Ali Khan, M. U. et al. Bending analysis of polymer-based lexible antennas for wearable, general IoT applications: a review. Polymers 13 (3), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13030357 (2021).

Zou, J. & Zhang, Q. Advances and frontiers in Single-Walled carbon nanotube electronics. Adv. Sci. 8 (23), 2102860. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202102860 (2021).

Zhou, W., Bai, X., Wang, E. & Xie, S. Synthesis, structure, and properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 21 (45), 4565–4583. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200901071 (2009).

Balanis, C. A. Antenna theory: Analysis and design (4thed.). Wiley. (2016).

Maćkiewicz, A. & Ratajczak, W. Principal components analysis (PCA). Comput. Geosci. 19 (3), 303–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/0098-3004(93)90090-R (1993).

Zu, H. R. et al. Circularly polarized wearable antenna with low proile and low specific absorption rate using highly conductive grapheme IEEE antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 19 (12), 2354–2358. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2020.3033013 (2020).

Du, C., Li, X. & Zhong, S. Compact liquid crystal polymer based tri-band flexible antenna for WLAN/WiMAX/5G applications. IEEE Access. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2941212 (2019).

Youssef, A., Halkhams, I., El Alami, R., Jamil, M. O. & Qjidaa, H. A simulation study of dual band THz soft antenna for biomedical applications. Sci. Afr. 25, e02294 (2024).

Rubani, Q., Gupta, S. H. & Rajawat, A. A compact MIMO antenna for WBAN operating at Terahertz frequency. Optik 207, 164447 (2020).

Azani, M. A. S. M. & Abidin, Z. Z. Terahertz microstrip patch antenna for breast tumour detection. J. Electron. Voltage Application. 4 (1), 53–66 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of Qatar National Library (QNL) for funding the article processing charge (APC) for this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DjamilaZiani, Mohammed Belkheir and Allel Mokaddem: Conceptualization, Methodology, investigation, analysis, Mehdi Rouissat: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation. Samir Birahim Belhaouari: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology. All authors contributes in Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Belhaouari, S.B., Mokaddem, A., Ziani, D. et al. ML/GA-based performance optimization of PBG-enhanced THz microstrip patch antennas on PTFE–SWCNT. Sci Rep 15, 44111 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27963-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27963-1